Abstract

Metabolic obstacles of the tumor microenvironment remain a challenge to T-cell-mediated cancer immunotherapies. To better understand the interplay of immune checkpoint signaling and immune metabolism, this study developed and used an optimized metabolite extraction protocol for non-adherent primary human T-cells, to broadly profile in vitro metabolic changes effected by PD-1 signaling by mass spectrometry-based metabolomics and isotopomer analysis. Inhibitory signaling reduced aerobic glycolysis and glutaminolysis. A general scarcity across the panel of metabolites measured supported widespread metabolic regulation by PD-1. Glucose carbon fate analysis supported tricarboxylic acid cycle reliance on pyruvate carboxylation, catabolic-state fluxes into acetyl-CoA and succinyl-CoA, and a block in de novo nucleoside phosphate synthesis that was accompanied by reduced mTORC1 signaling. Nonetheless, exogenous administration of nucleosides was not sufficient to ameliorate proliferation of T-cells in the context of multiple metabolic insufficiencies due to PD-L1 treatment. Carbon fate analysis did not support the use of primarily glucose-derived carbons to fuel fatty acid beta oxidation, in contrast to reports on T-memory cells. These findings add to our understanding of metabolic dysregulation by PD-1 signaling and inform the effort to rationally develop metabolic interventions coupled with immune-checkpoint blockade for increased treatment efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immune-checkpoint blockade targeting programmed cell death 1 (PDCD1/PD-1) and its ligand CD274 (PD-L1) has shown promise for the treatment of tumors of various histologies, with long-term responses and limited toxicities in a subset of patients1. T-cells found at the tumor margin can infiltrate and proliferate within the tumor upon successful immune-checkpoint blockade2. The tumor microenvironment presents obstacles to T-cell infiltration, and there is a growing appreciation for the metabolic restrictions imposed, such as competition with tumor cells for glucose3. Thus, it may be advantageous to couple immune-checkpoint blockade with metabolic interventions, and to include metabolic robustness in the engineering of cytotoxic T-cells4. Detailed knowledge of T-cell metabolism in different contexts would be a prerequisite for the rational development of such strategies.

The study of metabolism changed radically with the ability to do systems-level analyses using mass spectrometry5. Currently, there is no consensus regarding how to prepare non-adherent mammalian cell samples for metabolomics, and even less guidance specific for immune cells6,7. Metabolomic studies of human T-cells have used as many as 30 million cells per replicate8,9, an input requirement which may prohibit profiling rare T-cell subsets. A typical extraction protocol for intracellular metabolites includes: (i) separation of cells from media, (ii) a wash step to eliminate remaining contaminating media metabolites, (iii) quenching of metabolism and extraction of metabolites. Separation and washing can be done rapidly with adherent cells, but centrifugation requires prolonged exposure to the wash solution, which ideally should maintain physiological conditions while minimizing post-harvesting metabolic activity.

The purpose of this study was to broadly profile metabolic changes in human T-cells effected by PD-1 axis signaling using mass spectrometry-based metabolomics analyzing a panel of 155 polar and semi-polar metabolites. We simulated in vitro a tumor-directed attack by primed T-cells and used recombinant human PD-L1 protein to engage the immune-checkpoint, without the use of target cells and ensuing issues of cell separation and contaminating metabolites. To ensure profiling physiological-range conditions, antibody-based activation was adjusted using melanoma cell line antigen presentation as a guide. Our approach to minimize input requirements and optimize readout included screening several candidate wash solutions. As a reference control, we tested the ability of our assay parameters to identify expected metabolic changes induced by substitution of glucose by galactose in culture media. Finally, we incorporated [U-13C] glucose tracer experiments and analyzed carbon fate by steady-state isotopomer distributions of metabolites to infer relative pathway activities. This is particularly useful for non-linear pathways with multiple possible contributing pathways, such as the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle10.

Results

Simulating an abortive T-cell tumor-directed attack

To simulate an abortive T-cell tumor-directed attack, we used stimulating antibodies, followed by recombinant human PD-L1 exposure in a plate-based system. Previously frozen PBMC were thawed and expanded for 7 days with induction of surface PD-1 (Supplementary Fig. S1) before T-cell isolation and treatment (Fig. 1a). Multi-parameter immuno-phenotyping of T-cell differentiation using this expansion protocol was previously published by our group11. We adjusted our treatment conditions to have the same cytokine-based output levels as a cell-based antigen presentation system. MART-1-specific transgenic human T-cells (F5 TCR) were co-cultured with peptide-presenting target cells and interferon gamma (IFNγ) release was used to gauge activation and inhibition. As expected, M202 melanoma and K562-A2.1 peptide-pulsed cells caused IFNγ release, contrary to mock-pulsed cells and M238 melanoma cells that do not present the peptide (Fig. 1b). At a similar level of activation using stimulating antibodies, the PD-L1 peptide efficiently inhibited IFNγ release (Fig. 1b).

a Schematic representation of T-cell treatment prior to metabolite extraction. PBMC are expanded using a clinical grade adoptive cell transfer protocol that leads to upregulation of PD-1 receptor on the surface of T-cells. Isolated T-cells are then seeded in plates with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies with or without recombinant human PD-L1 (rhPD-L1). b IFN gamma ELISA of 24 h supernatants. T-cells bearing an exogenously expressed MART-1-specific T-cell receptor (F5 TCR) were co-cultured with M202 melanoma cells that present MART-1 via HLA-A2.1, M238 cells that do not, K562 cells with exogenous expression of HLA-A2.1 pulsed with MART-126–35 peptide, or stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies without target cells. Anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibody-based activation of T cells is comparable to levels of cell-based melanoma antigen presentation. c Light microscopy images show changes in cellular morphology with certain wash solutions. Jurkat cells were exposed for the indicated time intervals. The ammonium acetate iso-osmotic wash buffer provides little tonicity and causes considerable swelling of the cells. The ice-cold ammonium bicarbonate solution in 60% methanol causes cell changes on contact. In contrast, such changes are not noted with the mannitol solution. d Principal component analysis of 137 of 155 profiled metabolites demonstrates that the variance of intracellular metabolite measurements increases as a function of time when exposed to the ammonium acetate solution. Spontaneously immortalized 3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblasts were exposed to a 0.9% NaCl or 150 mM ammonium acetate solutions for the indicated times. The ellipses were added for emphasis. e Correlation of profiled metabolites between mannitol and NaCl wash solutions. Triplicates of 2 × 106 Jurkat cells per condition. f Correlation of metabolite measurements of two-fold serially diluted samples. Values are corrected for the dilution factor. The dashed lines represent a perfect correlation. The solid colored lines are the best fit lines of the data. g Schematic model displaying the reduced flux of galactose metabolism ending with complete oxidation to CO2 compared to high glycolytic flux with glucose and production of lactate. h Supernatant lactate levels of activated primary human T-cells in glucose-containing or galactose-containing culture medium. Displayed are the summary results of three experiments, sampled from three replicate wells per condition (n = 9 vs. 9).

Optimization of metabolite collection and analysis

Next, we sought to find an appropriate wash solution for our intracellular metabolite extraction protocol. We reasoned that microscopy could provide a quick screen for drastic morphologic changes. Ammonium acetate, a common metabolite collection-protocol wash solution for adherent cells, caused Jurkat cells to swell over 4 min, while a methanol-based solution altered morphology on contact (Fig. 1c). To more formally assess the effect of ammonium acetate, we used adherent mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) cells, because their exposure time to NaCl 0.9% (isotonic) and ammonium acetate solutions could be easily controlled. The variability of measurements with ammonium acetate increased as a function of exposure length (Fig. 1d). To overcome the osmotic swelling, we chose to proceed with an isotonic solution. Metabolite profiles of Jurkat cells using NaCl vs. mannitol isotonic wash solutions were highly correlated, with R2 = 0.93 (Fig. 1e), and with mannitol preserving the measurement of more metabolites. To co-optimize for a low cellular input amount that can quantitatively detect a substantial number of metabolites, we first assessed the ability of serial two-fold dilutions to predict the metabolite levels of the maximum cell number sample and found a good albeit decreasing correlation across the range of dilutions (Fig. 1f). Nonetheless, the number of reproducibly measured metabolite levels was highest at 5 × 105 cells, although at the cost of detecting fewer metabolites. Further, our ability to confidently measure decreasing levels of metabolites of successive dilutions was best between 1 × 106 and 5 × 105 cellular inputs (Supplementary Fig. S2). Based on these comparisons, together with format considerations, we proceeded with 8.4 × 105 cells per replicate, using a mannitol wash solution.

To test our parameters for metabolic extraction in the context of measuring a metabolic change, we activated T-cells in galactose-containing medium, which is known to decrease glycolytic flux and force cells to respire (Fig. 1g)12. As anticipated, lactate production was suppressed in galactose-containing medium (Fig. 1h). After 24 h, we detected higher intracellular levels of Leloir pathway intermediates UDP-hexose and hexose-phosphate with galactose treatment (Table 1). Aspartic acid was also elevated, consistent with recent reports of respiration driving aspartate production in proliferating cells13,14. Glycolytic intermediates were higher in the glucose condition, as was UDP N-acetylglucosamine, a reflection of glucose availability for the hexosamine pathway15. These findings fit expectations based on the literature.

Profiling of PD-L1 checkpoint-induced metabolic changes reveals a block in de novo nucleoside phosphate synthesis

Next, we interrogated metabolic changes caused in primary human T-cells by PD1 axis signaling. After 72 h of treatment, we adequately measured 146 of 155 intracellular metabolites of our panel, and found most to be reduced by treatment (Fig. 2a). Intracellular levels of glycolytic intermediates were reduced (Fig. 2b), as were lactate levels in media (Fig. 2c). Consumption of glutamine and serine were also reduced (Fig. 2c). Relative levels of nucleoside phosphates were decreased (Fig. 2d).

a Overview of all profiled intracellular metabolites as measured by mass spectrometry. Positive values indicate higher levels in the treated condition (PD-L1). Dotted lines represent a two-fold change on the log2 scale. Values are capped at 100-fold. b Intracellular glycolysis pathway intermediates are lower in inhibited cells. c Compared to Fc control cells, less lactate and alanine are produced, and less glucose, glutamine, and serine are consumed. d Nucleoside phosphates are reduced and aspartic acid levels are increased by PD-L1. FDR: false discovery rate. †: FDR > 0.05. All values represent four experiments with triplicates of each condition and have FDR < 0.05 unless indicated otherwise.

To probe further, we performed isotopomer analysis. This showed that despite similar incorporation of heavy carbons from [U-13C] glucose into ribose, very little label was incorporated into nucleoside phosphates with PD-L1 treatment (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. S3). Isotopomer analysis further showed differential carbon labeling of Krebs cycle intermediates (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. S4). Based on these carbon tracing changes, we inferred a model of fluxes into the cycle. PD-1 signaling results in increased reductive carboxylation of pyruvate, anaplerosis of the cycle at acetyl-CoA and succinyl-CoA that could come from fatty acids and branched chain amino acids, less anaplerosis from glutamine, and less nucleoside synthesis despite higher relative levels of aspartate (Fig. 3c).

a Selected isotopomers of uridine monophosphate and ribose-5-phosphate that represent the contribution of fully labeled ribose-5-phosphate (UMP M5) plus partially labeled aspartic acid (UMP M6–7). b Selected isotopomers of TCA metabolites used to infer metabolite contributions to the TCA cycle, expressed as the percentage of all isotopomers detected for the respective compounds. M0: unlabeled. M2: Two heavy carbons from glucose. M3: Three heavy carbons from glucose. c Schematic of inferred relative contributions to the TCA cycle in PD-L1-treated cells. Thick arrows represent more relative contribution of metabolites in the PD-L1-treated cells compared to the Fc control.

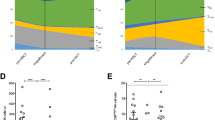

We questioned whether the block in nucleoside phosphate synthesis was an early event. At a 24 h time-point, the landscape of metabolic changes was consistent but more modest than at 72 h (Supplementary Fig. S5). Among relative level changes caused by PD-L1 treatment with an FDR < 0.05, we found reduced ribose-5-P and UMP, and increased aspartic acid (Fig. 4a). The inhibited cells incorporated less 13C from ribose-5-P into nucleoside phosphates, as reflected in their M5 isotopomers. At this early timepoint, the fold reduction was larger for pyrimidines than purines (Fig. 4b). The mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) has been shown to regulate nucleoside phosphate synthesis16,17. We probed phosphorylation sites on downstream targets of mTORC1, including carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 2, aspartate transcarbamylase, and dihydroorotase (CAD), and found decreased mTORC1 activity with PD-L1 treatment (Fig. 4c). In certain cellular contexts, isolated deficiency of nucleoside phosphate synthesis can be rescued by providing exogenous downstream substrates, including nucleosides16,17,18. However, in this checkpoint context, we could not document a rescue of proliferation in PD-L1-treated cells supplemented with exogenous nucleosides (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. S6).

a Relative levels of nucleoside phosphates and aspartic acid at 24 h of treatment. b Statistically significantly changing 13C incorporation into nucleoside phosphates from [U-13C] glucose via ribose-5-P, as reflected in the their M5 isotopomers. All measurements have a FDR < 0.05 but the fold-reduction is larger for pyrimidines than for purines. c Western blot of phosphorylation status of mTORC1 targets. T-cells were treated for 48 h as indicated. Jurkat cells were treated for 2 h. PHA: phytohemagglutinin 5 µg/mL. Rapa: rapamycin 20 nM. d Metabolic activity (alamar blue resazurin reduction) assay of Fc and PD-L1-treated T-cells with or without nucleoside cocktail supplementation for 48 h. Summary of three experiments performed on separated days in triplicates (n = 9 per condition).

Inhibition of mTOR partially phenocopies the PD-L1-mediated block in de novo nucleoside phosphate synthesis

We questioned whether the block in pyrimidine nucleoside phosphate synthesis could be solely attributed to mTORC1 inhibition, or whether additional PD-L1-activated mechanisms were responsible for the magnitude of the phenotype and its refractoriness to reversal by exogenous nucleoside administration. To address this question we similarly stimulated and expanded T-cells for 7 days and then treated for 48 h with rapamycin, a known inhibitor of mTORC1 and an immunosuppressant used clinically19. We found that low doses of rapamycin were sufficient to block phosphorylation of p-70 S6 kinase and its target phosphorylation site on CAD, although phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 was only reduced at much higher doses (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. S7). We next measured intracellular nucleoside phosphate levels and found lower levels upon rapamycin treatment (Fig. 5b), yet the effect was smaller than with PD-L1 treatment for 72 h (Fig. 2d). We confirmed that exogenous unlabeled nucleosides could be incorporated in the intracellular metabolite pool by measuring the fraction of [U-13C] glucose-derived label. Glucose-derived heavy carbon labeling could be competitively depleted by increasing concentrations of unlabeled nucleosides (Fig. 5c). However, similarly to the PD-L1 treatment, mTOR inhibition could not be circumvented by the administration of the nucleoside cocktail, as measured by the metabolic activity (resazurin reduction capacity) of the treated T-cells (Fig. 5d).

a T-cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of rapamycin for 48 h and levels of mTORC1 phosphorylation targets were assayed by western blot. b Rapamycin treatment reduces relative intracellular levels of nucleoside phosphates. Summary of two experiments run in triplicates (n = 6, 6) assayed at a 48 h time-point. c Supplementation of unlabeled nucleosides results in a decrease of glucose-derived heavy carbon label incorporation into nucleoside phosphates at 48 h. Results of two experiments with all conditions run in triplicate. d Metabolic activity (alamar blue resazurin reduction) assay of T-cells treated with 20 nM rapamycin for 48 h and additionally treated with the indicated concentrations of nucleoside cocktail.

Discussion

Our motivation to study human T-cell metabolism led us to develop an in vitro platform where cells can be activated and treated with ligands, drugs, or different nutrient conditions, and metabolic changes can be measured by LC/MS, with the use of an extraction protocol optimized for T-cells. This approach enabled us to exhibit a landscape of metabolic changes caused by PD-1 checkpoint engagement. Our study is unique, in that we have used a cell-based antigen presentation system as a guide for relevant in vitro artificial stimulation, and used [U-13C] glucose, to infer pathway activities and substrate utilization in PD-L1-treated primary human T-cells. This strategy allowed us to uncover a PD-L1-induced block in de novo nucleoside phosphate synthesis, although it remains an in vitro study of a single signaling pathway and cannot fully capture the complexities of the tumor microenvironment.

There are several proposed methods for metabolite extraction of non-adherent cells. We found isotonic solutions to be the most appropriate for washing (Fig. 1c, d) and chose to work with mannitol because it is compatible with both LC/MS and capillary electrophoresis technologies20. Early in our investigation we evaluated a filter-based method originally applied to microbial extraction that did not require pumps and automation21, but despite experimenting with several filter types and sizes we found filter clogging to be an issue. This limitation and reports of suboptimal recovery of metabolites from filters6 led us to prioritize a centrifugation-based strategy. A methanol-based wash solution22 distorted cells on contact (Fig. 1c) and has been reported to cause leakage of metabolites6, leading us to consider this option no further. Ammonium acetate is a common metabolite extraction wash solution because it is volatile and should not contribute to ion suppression after evaporation during sample preparation. A study with primary focus on lipidomics in Jurkat cells concluded that ammonium acetate is appropriate for human non-adherent cell metabolomics7. In our work, we found that it causes cells to swell. Penetration of mammalian cells by ammonium salts of weak acids has been studied23. More importantly, we found metabolite variability increased as a function of time exposed to ammonium acetate (Fig. 1d). However, we analyzed polar metabolites and do not know whether the lipid compartment is similarly affected.

We found that PD-1 inhibitory signaling shifts metabolism away from aerobic glycolysis and glutaminolysis (Fig. 2b, c), and forces the cell to utilize alternative substrates to feed the TCA cycle (Fig. 3b, c), in agreement with previous reports9,24. The single other mass spectrometry-based metabolomics study related to PD-1 signaling9 reported a block in the uptake and utilization of branched chain amino acids (BCAA), based on relative levels of intracellular and extracellular valine, and intracellular levels of the downstream metabolite 4-methyl-2-oxopentanoate. Induction of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I expression and increased mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity were also demonstrated, reminiscent of findings in murine T-memory cells25. In contrast to T-memory cells, lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) was not increased while adipose triglyceride lyase (ATGL) protein levels were. ATGL appears dispensable for T-cell memory25. We showed that unlabeled carbons enter the TCA cycle as acetyl-CoA (Fig. 3c), which does not support the idea of PD-L1-treated cells engaging in “cell-intrinsic lipolysis”. This term refers to the futile diversion of glucose-derived carbon into triglyceride synthesis by T-memory cells, only to be mobilized from lysosomes to re-enter the TCA cycle25. Thus, fatty acid beta-oxidation appears qualitatively different between PD-1-signaling cells and T-memory cells. Future studies are required to elucidate whether these early metabolic differences between PD-1-signaling cells and T-memory cells are causally linked to their distinct epigenetic profiles and potential for reinvigoration26,27. Considering the block of BCAA catabolism reported with PD-1 signaling9, the increase of unlabeled carbons we documented entering the TCA cycle at succinyl-CoA (Fig. 3c) must be attributed to the terminal three carbons of odd-chain fatty acids alone. However, our study does not provide the fractional contribution of each substrate to definitively confirm a block in BCAA catabolism, nor can we discount effects that our different treatment conditions could have had on those fractions.

For the first time, we demonstrated that PD-1 signaling results in a block of nucleoside phosphate de novo synthesis. This was more notable for pyrimidines at an early, 24 h timepoint (Fig. 4b). The difference in timing is consistent with pyrimidine de novo synthesis being controlled rapidly by mTORC1 phosphorylation of CAD and the control of purine synthesis being regulated through slower transcriptional mechanisms16,17. Indeed, we observed less phosphorylation of canonical mTORC1 targets and CAD (Fig. 4c). Activated T-lymphocytes are dependent on de novo purine and pyrimidine synthesis for proliferation and survival, and nucleotides regulate their cell cycle28. Nonetheless, a cocktail of purines and pyrimidines by itself was not sufficient to rescue the proliferation of PD-L1-treated cells (Fig. 4d). Additionally, mTOR inhibition by rapamycin treatment only partially phenocopied the block in nucleoside phosphate de novo synthesis and incorporation of glucose-derived heavy carbons, even though the phosphorylation of CAD and p-70 S6K was effectively inhibited (Fig. 5a). On the one hand, this suggests that S6K activity is not the only determinant of de novo pyrimidine and purine synthesis, although required for full capacity. Rapamycin-resistant T-cell proliferation has been documented in the context of strong T-cell receptor stimulation19, which would require such residual ability to synthesize RNA and DNA building blocks. On the other hand, even the partial inhibition by rapamycin was not circumventable by the provision of exogenous nucleosides. In fact, this intervention appeared to be further deleterious to the metabolic fitness of the cells (Fig. 5d). Possibly, this is an indication of substrate level negative feedback29. While we did not identify an effective maneuver to clearly define the role of mTOR in the context of PD-L1 signaling, conceivably there may be a combination of individual nucleoside concentrations that would have a positive effect. Based on the more profound inhibition with PD-L1 compared to rapamycin it is tempting to invoke other nodes of metabolic regulation, in addition to the central role and multiple functions described for mTOR in T-cell biology30. PD-1 signaling also inhibits AKT, another central regulator of proliferation and metabolism24. Furthermore, PD-1 inhibits the cell cycle through upregulation of p27kip1, in contrast to the PI3K-dependent downregulation of p27kip1 described in rapamycin-resistant T-cell proliferation19,31.

Future in vivo studies with transgenic animals will likely be required to expand on our findings and define which metabolic interventions can be coupled with immunotherapies for increased therapeutic efficacy.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from a healthy donor by leukapheresis under UCLA IRB#10-001598. M202 and M238 were established from patient biopsies with informed consent from all subjects under UCLA institutional review board approval IRB#02-08-06732. The K562-A2.1 cell line was a kind gift of Dr. Cedric Britten33. Human PBMCs, Jurkat cells, M202 and M238 melanoma cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with glutamine and supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% streptomycin, penicillin, and fungisome antibiotic cocktail (100x SPF, 10,000 units/mL penicillin, 10,000 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 25 µg/mL Amphotericin B). Immortalized MEF were cultured in DMEM with 10% FCS and 1% SPF. MEFs were immortalized as previously described34.

T-cell-directed expansion of PBMCs

Human PBMCs were expanded toward the T-cell lineage as previously described11 using 10% FCS instead of human AB serum. Medium acidity was monitored and fresh medium added every 2 days to maintain a concentration of 7 × 105 cells/mL.

T-cell activation and treatment with PD-L1

Twelve-well non-tissue culture-treated plates (Corning #351143) were coated at 4 °C overnight with 1 µg/mL anti-CD3 antibody (BD biosciences 555329) and 1.5 µM human IgG Fc fragment (Jackson Immunoresearch #009-000-008) or 1.5 µM recombinant human Fc-tagged PD-L1 (rhPD-L1.Fc) (Sino Biological #10084-H02H) in 1.2 mL PBS per well. The plate was washed twice with 2 mL PBS and blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 1.5 mL human serum albumin 2.5% in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS), followed by two more washes with PBS. T-cells previously expanded for 7 days were isolated by immunomagnetic negative enrichment kit (ThermoFisher #11344D) and seeded in triplicate wells at 8.4 × 105cells in 1.2 mL glucose-free RPMI (ThermoFisher #11879020) supplemented with 10 mM [U-13C] glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories #CLM-1396-PK), 10% dialyzed fetal calf serum, 1% SPF, and 1 µg/mL anti-CD28 antibody (BD biosciences #555725). For 72-h treatments, the treatment medium was refreshed 24 h prior to harvest.

T-cell metabolite extraction protocol

Treated T-cells were harvested into microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 500×G-force for 4 min. The medium was collected and stored at −80 °C until further processing. Ice-cold 5.4% mannitol wash solution was added, 1 mL to each pellet, and centrifuged with the same parameters at 4 °C. Subsequent steps were performed on ice with solutions ice-cold. The wash solution was removed and sequentially 250 µL methanol, 250 µL water, and finally 250 µL chloroform were added, vortexing briefly between steps. The mixture was centrifuged at 16,000×G-force for 5 min. The top polar phase was collected into glass chromatography vials and stored at −80 °C until further processing. Interphase protein was measured by BCA assay kit (ThermoFisher #23225). The polar phase, 20 µL of the supernatants, and three mock-extracted controls per run (polar phase of extraction mixture without cells) were evaporated with an EZ2-Elite centrifugal evaporator for 80 min on HPLC setting with 30 °C maximum temperature. The samples were block-randomized and stored at −80 °C prior to recovery and submission of 1/10 of each replicate for mass spectrometry. Additional extraction methods tested are described in the supplemental methods.

Co-culture of transgenic T-cells with melanoma and K562 targets

Transgenic MART-1-specific TCR-bearing T-cells (F5 cells) were co-cultured at 1:1 effector to target ratio for 24 h with melanoma, or either pulsed (MART-126–35) or non-pulsed K562-A2.1 cells in 24-well plates with 1 × 106 cells in 1 mL as previously described35. IFNγ release was assayed by ELISA (ThermoFisher #88-7316-77).

Western blotting

Primary antibodies used were Phospho-CAD (Ser1859) Antibody #12662, Phospho-p70 S6 Kinase (Thr389) (108D2) Rabbit mAb #9234, Phospho-4E-BP1 (Ser65) (174A9) Rabbit mAb #9456, and β-Actin (D6A8) Rabbit mAb #8457 from Cell Signaling.

Data analysis

Mass spectrometry metabolomics data were mean-normalized between runs. Significant changes were calculated using a two-sided Student’s t-test assuming unequal variance. P-values were adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing using Benjamini and Hochberg’s method of false discovery rate (FDR). Analysis was performed in R36.

References

Sharma, P. & Allison, J. P. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 348, 56–61 (2015).

Tumeh, P. C. et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515, 568–571 (2014).

Anderson, K. G., Stromnes, I. M. & Greenberg, P. D. Obstacles posed by the tumor microenvironment to T cell activity: a case for synergistic therapies. Cancer Cell 31, 311–325 (2017).

Irving, M., Vuillefroy de Silly, R., Scholten, K., Dilek, N. & Coukos, G. Engineering chimeric antigen receptor T-cells for racing in solid tumors: don’t forget the fuel. Front. Immunol. 8, 267 (2017).

Patti, G. J., Yanes, O. & Siuzdak, G. Innovation: metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 263–269 (2012).

Dietmair, S., Timmins, N. E., Gray, P. P., Nielsen, L. K. & Krömer, J. O. Towards quantitative metabolomics of mammalian cells: development of a metabolite extraction protocol. Anal. Biochem. 404, 155–164 (2010).

Ulmer, C. Z., Yost, R. A., Chen, J., Mathews, C. E. & Garrett, T. J. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry metabolic and lipidomic sample preparation workflow for suspension-cultured mammalian cells using Jurkat T lymphocyte cells. J. Proteom. Bioinform. 8, 126–132 (2015).

Wang, R. et al. The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity 35, 871–882 (2011).

Patsoukis, N. et al. PD-1 alters T-cell metabolic reprogramming by inhibiting glycolysis and promoting lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation. Nat. Commun. 6, 6692 (2015).

Buescher, J. M. et al. A roadmap for interpreting 13C metabolite labeling patterns from cells. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 34, 189–201 (2015).

Tumeh, P. C. et al. The impact of ex vivo clinical grade activation protocols on human T-cell phenotype and function for the generation of genetically modified cells for adoptive cell transfer therapy. J. Immunother. 33, 759–768 (2010).

Robinson, B. H. [39] Use of fibroblast and lymphoblast cultures for detection of respiratory chain defects. In Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 264 (ed. Giuseppe M. Attardi, A. C.) 454–464 (Academic Press, 1996).

Sullivan, L. B. et al. Supporting aspartate biosynthesis is an essential function of respiration in proliferating cells. Cell 162, 552–563 (2015).

Birsoy, K. et al. An essential role of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in cell proliferation is to enable aspartate synthesis. Cell 162, 540–551 (2015).

Wellen, K. E. et al. The hexosamine biosynthetic pathway couples growth factor-induced glutamine uptake to glucose metabolism. Genes Dev. 24, 2784–2799 (2010).

Ben-Sahra, I., Howell, J. J., Asara, J. M. & Manning, B. D. Stimulation of de novo pyrimidine synthesis by growth signaling through mTOR and S6K1. Science 339, 1323–1328 (2013).

Ben-Sahra, I., Hoxhaj, G., Ricoult, S. J. H., Asara, J. M. & Manning, B. D. mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science 351, 728–733 (2016).

Patel, D. et al. Aspartate rescues S-phase arrest caused by suppression of glutamine utilization in KRas-driven cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 9322–9329 (2016).

Slavik, J. M., Lim, D.-G., Burakoff, S. J. & Hafler, D. A. Rapamycin-resistant proliferation of CD8+ T cells correlates with p27kip1 down-regulation and bcl-xL induction, and is prevented by an inhibitor of phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 910–919 (2004).

Kim, D. et al. SHMT2 drives glioma cell survival in ischaemia but imposes a dependence on glycine clearance. Nature 520, 363–367 (2015).

McCloskey, D., Utrilla, J., Naviaux, R. K., Palsson, B. O. & Feist, A. M. Fast Swinnex filtration (FSF): a fast and robust sampling and extraction method suitable for metabolomics analysis of cultures grown in complex media. Metabolomics https://doi.org/10.1007/s11306-014-0686-2 (2014).

Sellick, C. A., Hansen, R., Stephens, G. M., Goodacre, R. & Dickson, A. J. Metabolite extraction from suspension-cultured mammalian cells for global metabolite profiling. Nat. Protoc. 6, 1241–1249 (2011).

Jacobs, M. H. & Stewart, D. R. The distribution of penetrating ammonium salts between cells and their surroundings. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 7, 351–365 (1936).

Parry, R. V. et al. CTLA-4 and PD-1 receptors inhibit T-cell activation by distinct mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9543–9553 (2005).

O’Sullivan, D. et al. Memory CD8(+) T cells use cell-intrinsic lipolysis to support the metabolic programming necessary for development. Immunity 41, 75–88 (2014).

Bengsch, B. et al. Bioenergetic insufficiencies due to metabolic alterations regulated by the inhibitory receptor PD-1 are an early driver of CD8+ T cell exhaustion. Immunity 45, 358–373 (2016).

Pauken, K. E. et al. Epigenetic stability of exhausted T cells limits durability of reinvigoration by PD-1 blockade. Science 354, 1160–1165 (2016).

Quéméneur, L. et al. Differential control of cell cycle, proliferation, and survival of primary T lymphocytes by purine and pyrimidine nucleotides. J. Immunol. 170, 4986–4995 (2003).

Lane, A. N. & Fan, T. W.-M. Regulation of mammalian nucleotide metabolism and biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 2466–2485 (2015).

Wang, R. & Green, D. R. Metabolic checkpoints in activated T cells. Nat. Immunol. 13, 907–915 (2012).

Patsoukis, N., Sari, D. & Boussiotis, V. A. PD-1 inhibits T cell proliferation by upregulating p27 and p15 and suppressing Cdc25A. Cell Cycle 11, 4305–4309 (2012).

Søndergaard, J. N. et al. Differential sensitivity of melanoma cell lines with BRAFV600E mutation to the specific Raf inhibitor PLX4032. J. Transl. Med. 8, 39 (2010).

Britten, C. M. et al. The use of HLA-A*0201-transfected K562 as standard antigen-presenting cells for CD8+ T lymphocytes in IFN-γ ELISPOT assays. J. Immunol. Methods 259, 95–110 (2002).

Graham, N. A. et al. Recurrent patterns of DNA copy number alterations in tumors reflect metabolic selection pressures. Mol. Syst. Biol. 13, 914 (2017).

Comin-Anduix, B. et al. The oncogenic BRAF kinase inhibitor PLX4032/RG7204 does not affect the viability or function of human lymphocytes across a wide range of concentrations. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 6040–6048 (2010).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Heather Christofk, and members of our labs for helpful suggestions. This study was funded by the NIH/NCI grants P01 CA168585, R21 CA169993, R35 CA197633, and R01 CA170689. T.G.G. is supported by an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award (RSG-12-257-01-TBE), a Melanoma Research Alliance Established Investigator Award (20120279), and the UCLA Jonsson Cancer Center Foundation. A.R. is supported by the Dr. Robert Vigen Memorial Fund, the Garcia-Corsini Family Fund, the Ressler Family Fund, and the Grimaldi Family Fund. N.J.P. was partially supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award 5T32CA009297-30 (T32) and the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant KL2TR001882.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.J.P., T.G.G., and A.R. conceptualized the project, N.J.P. designed and performed all experiments, J.D.G., R.S., D.S.S., and D.B. data acquisition, C.P.-S. produced engineered T-cells, N.J.P. and T.G.G. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

T.G.G. reports receiving honoraria from Amgen, having consulting and equity relationships with Trethera Corporation. The lab of T.G.G. has completed a research agreement with ImmunoActiva. A.R. reports personal fees from consulting with Amgen, Chugai, Genentech-Roche, Novartis, Merck, Sanofi, and being a member of the scientific advisory board of Arcus, Bioncotech, Compugen, Cytomx, Five Prime, FLX-Bio, Merus, Rgenix, PACT Pharma, and Tango Therapeutics.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Palaskas, N.J., Garcia, J.D., Shirazi, R. et al. Global alteration of T-lymphocyte metabolism by PD-L1 checkpoint involves a block of de novo nucleoside phosphate synthesis. Cell Discov 5, 62 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-019-0130-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-019-0130-x