Abstract

Obesity is a risk factor for many chronic diseases, and is associated with increased incidence rate of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia and cardiovascular diseases. Adipocyte differentiation play critical role during development of obesity. Latexin (LXN), a mammalian carboxypeptidase inhibitor, plays important role in the proliferation and differentiation of stem cells, and highlights as a differentiation-associated gene that was significantly downregulated in prostate stem cells and whose expression increases through differentiation. However, it is unclear whether LXN is involved in adipocyte differentiation. The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of LXN on adipocyte differentiation, as well as its effects on high fat-induced obesity and metabolic disorders. In this study, we determine the expression of LXN in adipose tissue of lean and fat mice by Western blot, qPCR and immunohistochemistry. We found that LXN in fat tissues was continuous increased during the development of diet-induced obesity. We fed wild-type (WT) and LXN−/−mice with high-fat diet (HFD) to study the effects of LXN on obesity and related metabolic functions. We found that mice deficient in LXN showed resistance against high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity, glucose tolerance, insulin tolerance and hepatic steatosis. In vitro studies indicated that LXN was highly induced during adipocyte differentiation, and positively regulated adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells and primary preadipocytes. Functional analysis revealed that the expression of LXN was positively regulated by mTOR/RXR/PPARɤ signaling pathway during the differentiation of adipocytes, while LXN deletion decreased the protein level of PPARɤ in adipocyte through enhancing FABP4 mediated ubiquitination, which led to impaired adipocyte differentiation and lipogenesis. Collectively, our data provide evidence that LXN is a key positive regulator of adipocyte differentiation, and therapeutics targeting LXN could be effective in preventing obesity and its associated disorders in clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a risk factor for many chronic diseases. Obesity and associated comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), hypertension, heart diseases and stroke, represent the most common health risks worldwide [1,2,3], and becoming one of the growing fundamental problem of human diseases in developing and underdeveloped countries. It is estimated that more than 4 million people die from overweight or obesity each year, and this figure is on the rising [4]. The prevalence of obesity has become a major burden on the global health system. Hence, the understanding of the molecular events in process of obesity is of growing importance.

Adipose tissue is a complex organ regulating energy balance, which is mainly composed of adipocytes surrounded by fibroblasts, fibroblastic preadipocytes, endothelial cells and immune cells [5]. Differentiation of preadipocytes into mature adipocytes is one of the important mechanisms of adipose tissue formation and obesity. During the development of obesity, adipose tissue expands through an increase in the size of preexisting adipocytes as well as through the formation of new adipocytes from preadipocytes resulting in an increased number of adipocytes [6]. In this regarding, mounting evidences suggest that differentiation of adipocytes from mesenchymal precursors is an important process for maintaining functional adipose tissues [7, 8]. Therefore, regulation of preadipocyte differentiation may be an effective way to treat obesity and related metabolic diseases.

Multiple signaling pathways and mediators have been described to regulate adipocyte differentiation such as bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling, mTOC signaling and PPARγ/RXRα [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Among them, PPARγ as the dominant regulator of adipogenic differentiation was well studied. The expression of PPARγ is not only induced early during adipocyte differentiation but also continues at high level in mature adipocytes, suggesting that PPARγ may also play have important role in fully differentiated adipocytes [16]. Latexin (LXN), a mammalian carboxypeptidase inhibitor, was originally identified in the lateral neocortex of rats and widely expressed in tissues and cells including intestines, hematopoietic and lymphoid organs [17, 18]. Previous studies showed that LXN plays an important physiological role in stem cells proliferation and differentiation. For example, Liang et al. identified LXN as a stem cell regulatory gene with expression that negatively correlates with haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) number variation in different mouse strains [19], and they further reported that ablation of LXN enhanced long-term repopulating capacity and survival of HSCs through regulating the expression of Thbs1 [20]. Kadouchi et al. reported that the expression of LXN is induced by BMP-2 in mesenchymal cells during chondrocyte and osteoblast differentiation, suggesting the important role of LXN in the cell differentiation [21, 22]. Oldridge et al. reported that LXN is a differentiation-associated gene that are highly significantly downregulated in prostate stem cells and whose expression increases through differentiation [23]. However, it is unclear whether LXN is involved in adipocyte differentiation.

In the present study, we examined the roles of LXN in adipocyte differentiation and obesity in mice. We show that LXN-deficient mice have reduced HFD-induced obesity and improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. We demonstrate that LXN is upregulated by mTOR/RXR/PPARɤ axis during adipocytes differentiation, and LXN deletion decreases the level of PPARɤ in adipocyte through enhancing FABP4 mediated ubiquitination.

Results

Expression of LXN is upregulated in adipose tissue of mice by body adiposity

We first analyzed the expression of LXN in obese rat or mice fat tissues based on GEO profile database (GEO profiles: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geoprofiles). We found that LXN was significantly upregulated in epididymal adipose tissue of diet-induced obese rat (GEO 44671117) (Fig. S1A). In mice, we found that mice with high weight gain had more LXN expression in adipose tissue compared with mice with low body weight gain (GEO 30162583) (Fig. S1B). We next examined the protein level of LXN in lean and obese mice. We constructed leptin receptor mutant mice (ob/ob) with C57/BL6 background. Compared with C57/BL6 mice (WT), ob/ob mice fed with normal diet (ND) gained more weight gain (Fig. 1A). The protein and mRNA level of LXN were much higher in adipose tissues in ob/ob mice than those in WT mice (Fig. 1B, C, D). When C57/BL6 mice were induced to develop obesity by feeding with high-fat diet (HFD), the expression of LXN in adipose tissues was significantly upregulated after 8-23 weeks of HFD feeding (Fig. 1E, F). These data suggest that the expression of LXN is positively correlated with obesity in mice.

A Representative pictures for WT and ob/ob mice after feeding with normal diet (ND) for 16 weeks. B, C QPCR (B) and Western blot (C) analysis for LXN in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of WT and ob/ob mice. The bar graphs showing the results of all animals examined. Data are mean ± SD. **P < 0.01 vs. WT. D Immunohistological analysis of LXN expression in adipose tissues of WT and ob/ob mice. Scale bars, 200 μm. E, F 8-week-old male C57/B6 mice (n = 6) were fed with high fat-diet (HFD) for additional 8, 14 or 23 weeks, then adipose tissue were harvested. LXN was determined by QPCR (E) and western blot (F). The bar graph shows quantification of LXN level in all animals examined. **P < 0.01 vs. 0 W.

Mice deficient in LXN are protected from HFD-induced obesity

We next sought to address the impact of LXN on the development of obesity. For this purpose, 8-week-old LXN−/− and control littermates were fed with HFD for 23 weeks. We found that overall body weight gain was higher in HFD-induced WT mice than that of LXN-/- mice (Fig. 2A, B). Importantly, the lower body weight in HFD-fed LXN-/- mice was predominantly featured by the reduction of white adipose tissue (WAT) mass such as the perirenal adipose tissue (WT = 2.68 ± 0.44 g vs. KO = 1.99 ± 0.55 g; P < 0.05) and subcutaneous white adipose tissue (sWAT) (WT = 3.53 ± 0.36 g vs. KO = 2.91 ± 0.28 g; P < 0.05) (Fig. 2C, D). Consistent with these observations, LXN−/− mice displayed significantly smaller size for adipocytes in perirenal adipose tissues and sWAT than those of wild-type mice fed with either ND or HFD (Fig. 2E, F). Collectively, these data provided evidence suggesting that LXN-deficient mice are resistant to HFD-induced obesity.

A Representative pictures for WT and LXN−/− mice after feeding with HFD or ND for 23 weeks. B Comparison of body weight changes between WT and LXN−/− mice during the course of ND or HFD induction (n = 8). ND-WT, WT mice fed with ND; ND-KO, LXN−/− mice fed with ND; HF-WT, WT mice fed with HFD; HF-KO, LXN-/- mice fed with HFD. C, D Representative pictures for perirenal adipose tissue (C) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (D) collected from WT and LXN-/- mice after 23 weeks of HFD or ND feeding, and analysis of the weight. E, F Representative pictures for H&E-stained perirenal adipose sections (E) and subcutaneous adipose sections (F) collected from WT and LXN-/- mice after 23 weeks of HFD or ND feeding. Scale bar = 200 μm. Mean adipocyte size was calculated. All results were presented as mean ± SD, and P values were calculated with use of Student t test. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01.

LXN is induced during adipocyte differentiation, and LXN deficiency inhibits adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis in vitro

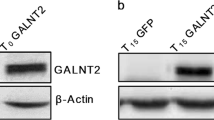

We confirmed the expression of LXN during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. The qPCR analyses revealed that the mRNA level of LXN increased after induction during adipocyte differentiation (Fig. 3A). As expected, these genes associated with adipocyte differentiation, such as PPARɤ, CEBPα and FABP4, were also induced (Fig. 3B). We further evaluated the effect of LXN on adipogenesis of preadipocytes. We determined the effect of LXN on adipocyte differentiation by using 3T3-L1 cells and primary preadipocytes from mice sWAT. In 3T3-L1 cells, differentiation medium (DM)-induced adipogenesis was significantly inhibited when LXN knockdown, however, enhanced by ectopic expression of LXN, as evidenced by lipid droplets determined by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 3C, D). Primary preadipocytes were isolated from sWAT of WT and LXN−/− mice. A significant reduction of adipocyte differentiation was observed in LXN−/− preadipocytes as compared with WT control when induced by DM (Fig. 3E, F). In contrast, the adipogenic ability of LXN-/- preadipocyte could be restored by ectopic expression of LXN (Fig. 3G). These data indicate that LXN positively regulates preadipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis, whereas LXN deficiency inhibits this process.

A, B 3T3-L1 cells were cultured with differentiation medium for 0,3 and 5 d, the mRNA level of LXN (A), PPARɤ, CEBPα and FABP4 (B) were determined by qPCR. C, D 3T3-L1 cells were transfected with LXN siRNA or flag-LXN plasmid. After 48 h, the cells were cultured with differentiation medium for 3 d. Cultured cells were subjected to Oil Red O staining (C) and imaged by EVOS microscope (D). EV empty vector, siCTL siRNA control, Scale bar = 50 μm. E, F WT and LXN−/− preadipocytes (KO) were cultured with differentiation medium for 3 d (E). Cultured cells were subjected to Oil Red O staining (F). Scale bar = 50 μm. G LXN−/− preadipocytes were transfected with flag-LXN plasmid or empty vector. The cells were cultured with differentiation medium for 3 d, and subjected to Oil Red O staining. Scale bar = 50 μm.

RNA-seq analysis reveals that LXN depletion in preadipocytes down-regulates PPARn targeted genes

To comprehensively understand the effect of LXN deficiency on adipocyte differentiation, we performed RNA-seq analysis with WT and LXN−/− preadipocytes. Preadipocytes from WT and LXN−/− mice were treated with NM or DM for three days. RNA-seq revealed that LXN ablation induced significant transcriptional changes of preadipocyte under normal medium or differentiation medium treatment (Fig. 4A, B), and suggested that LXN inhibition leads to the dysregulation of different subsets of transcriptional in the absence or presence of differentiation medium (Fig. 4C). To identified biological processes affected by LXN deficiency, we performed functional annotation by gene ontology (GO). We focused on the NM- and DM-induced WT preadipocytes (DM_WT vs. WT) and DM-induced WT and LXN−/− preadipocytes (DM_WT vs DM_KO). Our data show that those upregulated genes were enriched for fat cell differentiation, fatty acid metabolic process, fatty acid oxidation, lipid modification and lipid oxidation when WT preadipocytes were treated with DM for three days; whereas these gene groups were mostly downregulated in DM-induced LXN-/- preadipocytes as compared with DM-induced WT preadipocytes (Fig. 4D). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) further confirmed the upregulation of fatty acid metabolism and PPARɤ signaling signatures, including pro-adipogenesis genes (such as Fasn, Scd1, Scd2, Scd3 and Pparɤ) in DM-induced WT preadipocytes (Fig. 4E); whereas, under normal medium, LXN deficiency did not affect the mRNA level of PPARɤ, but significantly decreased retinoid x receptor (RXR) binding, retinoic acid receptor (RAR) binding and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) binding activities (Fig. 4F), indicating the important role of LXN in the RXR/PPAR mediated proliferation and differentiation of preadipocytes. Importantly, GSEA revealed that DM-induced fatty acid metabolism was dramatically inhibited in LXN−/− preadipocytes (Fig. 4G), which was characterized by decreasing of PPARɤ target genes such as Fasn [24, 25] Scd1 [25], Scd2 [26] and Scd3, compared with DM-induced WT preadipocytes (Fig. 4H). Overall, these data indicate that LXN deficiency inhibits adipocytes differentiation by reducing PPARɤ target genes.

A Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DGEs) in WT and KO preadipocytes cultured with normal medium (KO vs WT), WT preadipocytes cultured with normal medium and differentiation medium (DM_WT vs WT) and WT or KO preadipocytes cultured with differentiation medium (DM_KO vs DM_WT). B The overlapping genes identified in different experimental groups. C DEGs identified by RNA-seq were presented in Heatmap. D GO enrichment analysis of DEGs in DM_WT vs WT group (left) and DM_KO vs DM_WT group (right). E–G Heatmap shows the GSEA of representative KEGG pathway in WT preadipocytes cultured with differentiation medium or normal medium (E), WT and KO preadipocytes cultured with normal medium (F) and differentiation medium (G). H Real-time PCR results for analysis of LXN and PPARɤ targeted genes in WT or KO preadipocytes under normal medium or differentiation medium. All results were presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01, ns: no significance.

LXN is upregulated by activation of mTOR/RXR/PPAR/ signaling pathway during adipocytes differentiation and adipogenesis

The expression of LXN was upregulated in obese mice and could be induced by high-fat diet (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1). We then want to ask what the mechanism underline high-fat diet induces the expression of LXN. To this end, we assessed the expression of LXN during differentiation of preadipocyte by cultured cells with differentiation medium (DM) for 0, 3, 5, 7 days. We found that the LXN protein level began to increase after 3 days of DM induction and reached the maximum after seven days. As expected, the PPARɤ protein level was continued to rise during DM induction. Treatment of preadipocytes with DM activates mTOR, however, has little effect on the activation of AKT, although it increases the protein level of AKT (Fig. 5A, B). To expound the pathways underline LXN is upregulated during adipogenesis, DM-induced preadipocytes were treated with perifosine (AKT inhibitor) and rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor), respectively. Notably, the upregulation of LXN and PPARɤ in DM-induced preadipocytes were markedly inhibited by treatment with mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, rather than AKT inhibitor (Fig. 5C, D), indicating the critical role of mTOR for upregulation of LXN and PPARɤ in DM-induced preadipocytes. Furthermore, treatment with PPARɤ inhibitor GW9662 significantly inhibited the expression of LXN in DM-induced preadipocytes (Fig. 5E, F), indicating PPARɤ is a positive regulator of LXN expression and is located downstream of mTOR signal. Interestingly, the increased LXN by mTOR agonist 3BDO was reversed when RXRα antagonists PA452 present (Fig. 5G, H), indicating that RXRα:PPARɤ, a common heterodimer for regulating the expression of adipocyte genes, contributed to LXN expression. Oil Red O-staining of DM-induced preadipocytes further proved that inhibitors like GW9662, rapamycin and PA452 significantly suppress adipogenesis (Fig. 5I). We further analyzed the transcription factor binding site of ~3000 bp (-2973-1) upstream of the TSS site of mouse LXN gene (gene ID 17035) by using Jaspar online tool [27]. Total five putative sites were predicted with relative profile score threshold 80%, among them, 1 PPARɤ binding site and 4 PPARɤ::RxRa binding sites were predicted (Fig. 5J, and Supplementary Table S1). The binding activity of PPARɤ to the promoter region of LXN gene was confirmed in 3T3-L1 cells by ChIP experiment (Fig. 5K). So far, we identified the molecular signaling pathway involved in regulating the expression of LXN in preadipocytes (Fig. 5L), and strongly suggest that the expression of LXN is positively regulated by mTOR/RXR/PPARɤ signaling pathway during the differentiation of preadipocytes into adipocytes.

A, B 3T3-L1 cells were cultured in differentiation medium for 0, 3, 5, 7 d. Cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies (A) and then quantified and normalized (B). *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01 vs. 0 d. C, D 3T3-L1 cells were pre-treated with 10µmol/L perifosine (AKT inhibitor) or 20nmol/L rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor) for 12 h. After that, the cells were cultured with normal medium or differentiation medium for 3 d. The cell extracts were then subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies (C), and the relative protein levels of PPARɤ and LXN were assessed (D). E, F 3T3-L1 cells were pre-treated with 10 µmol/L GW9662 (PPARɤ antagonist) for 2 h, and then cells were cultured with normal medium or differentiation medium for 3 d. The cell extracts were then subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies (E), and the relative protein levels of PPARɤ and LXN were assessed (F). G, H Normal medium or differentiation medium-cultured 3T3-L1 cells were treated with 20 µmol/L 3BDO (mTOR agonist) for 12 h followed by treatment with 20 µmol/L PA452 (RXR antagonist) for an additional 60 h. to assess PPARɤ and LXN protein levels. The cell extracts were then subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies (G), and the relative protein levels of PPARɤ and LXN were assessed (H). I 3T3-L1 cells were cultured in differentiation medium with GW9662, rapamycin or PA452, respectively, for 3 d. Cultured cells were subjected to Oil Red O staining. Scale bar = 50 μm. J Prediction of PPARɤ and PPARɤ::Rxra binding sites in LXN promoter region (~3000 bp) by JASPAR CORE database (https://jaspar.genereg.net/). Pink, represents the predicted PPARɤ binding region; Green, represents the predicted PPARɤ::Rxra binding region; K 3T3-L1 cells cultured in normal medium (NM) and differentiation medium (DM) with or without GW9662 (PPARɤ antagonists) treatment for 3 d, and the binding activity of PPARɤ to LXN promoter in 3T3-L1 cells was determined by ChIP assay. L Schematic diagram to demonstrate the mechanism by which LXN was upregulated during preadipocyte differentiation. All results were presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01, ns: no significance.

LXN deficiency in preadipocyte decreases the stability of PPARɤ by enhancing FABP4 mediated ubiquitination

PPARɤ is recognized as a central coordinator of the adipogenic program, and acts as a direct activator of most adipocyte specific genes [15, 28, 29]. We observed that loss of LXN ameliorated HFD-induced obesity in mice and inhibited adipogenesis of adipocytes in vitro (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3), which prompted us to ask whether LXN deletion affects the expression of PPARɤ. To this end, WT and LXN-/- preadipocytes were treated with normal medium (NM) or differentiation medium (DM) for 3 days. As expected, preadipocytes cultured with DM significantly increase the protein level of PPARɤ and fatty acid binding protein (FABP4). However, LXN deletion dramatically attenuates the protein level of PPARɤ, but enhances that of FABP4, compared with WT preadipocytes under both NM and DM-treated conditions (Fig. 6A, B). Similar story occurred in 3T3-L1 cells treated with siLXN. Interestingly, the decrease in PPARɤ caused by LXN knockdown was restored when cells were treated with FABP4 inhibitor BMS (Fig. 6C, D). FABP4 is one of major target gene of PPARɤ, and FABP4 was induced by PPARɤ almost exclusively in adipocytes [30, 31]. Garin–Shkolnik et al. reported that FABP4 decreases PPARɤ protein level by accelerating its ubiquitination, suggesting a negative feedback loop between PPARɤ and FABP4 in adipocytes [32]. Therefore, our results demonstrate that inhibition of LXN in preadipocytes elevates FABP4 level, which acts as a negative regulator of PPARɤ, thus suggesting a positive feedback loop exists between LXN and PPARɤ in adipocytes.

A, B Primary preadipocytes isolated from WT and LXN−/− mice were cultured with normal medium (NM) or differentiation medium (DM) for three days. Cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies (A), and the relative protein levels of LXN, PPARɤ and FABP4 were assessed (B). C, D 3T3-L1 cells were transfected with scramble siRNA or LXN siRNA. Twelve hours later, the medium was changed, and the cells were cultured in the differentiation medium containing 20 µmol/L BMS (FABP4 inhibitor) for 3 days. The cell extracts were then subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies (C), and the relative protein levels of LXN, PPARɤ and FABP4 were assessed (D). E-G Normal medium-cultured 3T3-L1 cells were transfected with 0, 1, 3, 5 µg Flag-LXN plasmid, respectively, for 48 h. The cell extracts were then subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies (E), and relative quantification of FABP4 and PPARɤ were presented (F). The relative mRNA levels of FABP4 and PPARɤ were determined by qPCR (G). H qPCR determine the relative mRNA level of FABP4 (left) and PPAR ɤ (right) in WT and LXN-/- primary preadipocytes under normal medium or differentiation medium condition. I WT and LXN-/- primary preadipocytes were treated with CHX (350 mmol/L) and harvested at the indicated times after CHX addition. Immunoblots of cell extracts with antibodies directed against PPARɤ, LXN, and β-actin are shown (left). Half-life analysis of PPARɤ protein, relative to time 0 (right). J Overexpression of LXN by lentivirus in LXN-/- primary preadipocytes followed by CHX treatment for the indicated times. Immunoblots of cell extracts with antibodies directed against PPARɤ, LXN, and β-actin are shown (left). Half-life analysis of PPARɤ protein, relative to time 0 (right). K 3T3-L1 cells were transfected with scramble siRNA or LXN siRNA for 48 h. After that the cells were treated with 20 µmol/L BMS for 12 h, and then the cells were cultured with differentiation medium. After 48 h, the cells were treated with MG132 (0.1 µmol/L) for another 12 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-ubiquitin or anti-PPARɤ antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with antibodies directed against ubiquitin or PPARɤ. All results were presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, ns: no significance.

To strengthen the observations, we further determined the effect of LXN on the expression of PPARɤ and FABP4. To this end, normal medium-cultured 3T3-L1 cells were transfected with Flag-LXN plasmid. We found that the protein level of PPARɤ was increased in a dose-dependent manner with LXN, while the protein level of FABP4 was decreased with the enhanced expression of LXN (Fig. 6E, F). QPCR showed that ectopic expression of LXN significantly decreased FABP4 mRNA level in 3T3-L1 cells; however, had no effect on the level of PPARɤ mRNA (Fig. 6G). In contrast, we observed an increase of FABP4 mRNA in LXN deficient primary preadipocytes under both NM and DM-treated conditions (Fig. 6H, up). Although DM induced an increase in PPARɤ mRNA, no difference was observed between WT and LXN-/- preadipocytes absence or presence of differentiation medium (Fig. 6H, bottom). These results clarify that LXN regulates PPARɤ expression at the protein level rather than at the mRNA level.

We therefore examine the effect of LXN knockout on the stability of PPARɤ protein. Protein half-life analysis showed that PPARɤ protein became more unstable in LXN-deficient preadipocytes as compared with WT preadipocytes (Fig. 6I). However, LXN-/- preadipocytes ectopic expression of LXN by infected with lentivirus dramatically enhances PPARɤ stability (Fig. 6J), further suggesting that LXN positively regulates the stability of PPARɤ protein. We then sought to confirm the ubiquitination state of PPARɤ. As shown in Fig. 6K, although LXN knockdown had little effect on the overall ubiquitination level of 3T3-L1 cells, LXN knockdown significantly increased PPARɤ ubiquitination under normal medium condition. Differentiation medium treatment almost inhibited PPARɤ ubiquitination; however, this effect was reversed when LXN was knockdown. It was interestingly noted that the ubiquitination of PPARɤ caused by LXN knockdown is attenuated when cells were pre-treated with FABP4 inhibitor BMS, indicating that FABP4 indeed mediated the decrease of PPARɤ in LXN-/- adipocytes.

LXN deficiency improves HFD-induced metabolic disorders in mice

Metabolic disorder is a common complication of obesity. Since LXN deficiency can alleviate obesity induced by high-fat diet, we want to know whether LXN deficiency can also improve obesity complications, such as hepatosteatosis and insulin resistance. We challenged WT and LXN-/- mice with HFD feeding for a 23-week period. The concentration of triglycerides (TG) and cholesterol in plasma and liver tissue were determined. No significant difference in plasma triglyceride and cholesterol was observed between WT and LXN−/− mice on normal diet. However, mice deficient in LXN were manifested by the significantly lower levels of plasma TG and cholesterol than their littermate controls after 23 weeks of HFD induction (Fig. 7A), and the significantly lower levels of TG and cholesterol were noted in liver in LXN-/- mice under HFD, as well (Fig. 7B). In line with these observations, hepatic steatosis was detected in HFD-fed WT mice as featured by the significant change of liver color and weight as compared with that of LXN-/- mice (Fig. 7C). Histologic analysis of the liver from WT mice on HFD showed macrovesicular hepatic steatosis as evidenced by a fatty liver populated with abundant large vacuolar lipid droplets, whereas the liver of LXN−/− mice had few lipid droplets, as determined by H&E and Oil Red O staining (Fig. 7D, E). Moreover, mRNA expression levels of inflammatory markers (such as iNOS, IL-6 and TNF-α) (Fig. 7F) and the immunofluorescence staining (F4/80) supported the histological evidence for reduced inflammation in the livers of LXN-/- mice (Fig. 7G).

A, B Results for TG and cholesterol levels in plasma (A) and liver (B) of WT and LXN-/- mice fed a ND or HFD for 23 weeks (n = 8). C Comparison of liver weight. Top: Representative pictures for livers collected from WT and LXN−/− mice. Bottom: Results for liver weight (n = 8). D, E Representative results for H&E staining (D) and Oil Red O staining (E) of liver sections. Scale bar = 200 μm. F Real-time PCR results for analysis of inflammation marker genes in liver (n = 8). G Representative pictures for immunofluorescence staining of F4/80 of liver sections. Scale bar = 100 μm. All results were presented as mean ± SD, and P values were calculated with use of Student t test. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01, ns: no significance.

A chronic HFD treatment would result in obesity-associated insulin resistance in mice [2, 6, 15]. We also performed glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity tests to examine the effect of LXN deficiency on HFD-induced insulin resistance. We placed LXN−/− and WT mice on a normal diet or HFD for 16 weeks. WT and LXN−/− mice were fed with HFD, which resulted in different body weight gain of mice, and LXN−/− mice gained lighter body weight (Fig. 8A) accompanied with the markedly lower triglyceride and cholesterol level in both perirenal adipose tissue and sWAT compared with WT mice on HFD condition (Fig. 8B, C). Interestingly, HFD-induced LXN-/- mice exhibited a lower blood glucose compared with WT mice (Fig. 8D), but there was no significant difference in plasma insulin level (Fig. 8E), suggesting the lower plasma glucose levels are caused by increased insulin sensitivity.

A Body weight in WT and LXN−/− mice fed a ND or HFD for 16 weeks (n = 8). B, C Results for TG and cholesterol levels in perirenal adipose tissue (B) and sWAT (C) of WT and LXN-/- mice fed a ND or HFD for 16 weeks (n = 8). D, E Analysis of fasting plasma glucose (D) and insulin (E) levels. All mice were fasted for 12 h before the analysis. F Results for intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (GTT) (left) and area under the curve (AUC) for the blood glucose levels (right). G Results for intraperitoneal insulin tolerance tests (ITT) (left) and AUC for the blood glucose levels (right). For the GTT, fasting overnight mice were gavage fed with a 2 mg glucose/g body wt glucose load. For the ITT, mice fasted for 6 h were intraperitoneally injected with 0.5 U insulin/kg body wt using an insulin syringe. ND-WT, WT mice fed with ND; ND-KO, LXN−/− mice fed with ND; HF-WT, WT mice fed with HFD; HF-KO, LXN-/- mice fed with HFD. H Western blot analysis for p-AMPK, total AMPK, and LXN in the sWAT. I Western blot analysis for p-IRS1 (Ser307), total IRS1, p-AKT (Ser473), and total AKT in the sWAT. Mice were fasted overnight and injected intraperitoneally with insulin (1U/kg body wt). Tissues were excised 15 min after injection for immunoblotting analyses. All results were presented as mean ± SD, and P values were calculated with use of Student t test. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01, ns: no significance.

We therefore carried out glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity tests to determine the effects of LXN deficiency on glucose metabolism. Unlike their WT littermates, LXN-/- mice were characterized by the significantly improved glucose tolerance (Fig. 8F) and insulin sensitivity (Fig. 8G). Importantly, Western blot analysis showed that LXN loss obviously promote the phosphorylation of AMPK in sWAT of HFD-induced mice (Fig. 8H). Furthermore, Western blot analysis of IRS1 and AKT, the two critical insulin-signaling molecules, revealed that sWAT from LXN-/- mice injected with insulin was featured by the significantly increased phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT, Ser473) and IRS1 (p-IRS1, Ser307) as compared with their control counterparts following 16 weeks of HFD induction (Fig. 8I). Taken together, these results provided evidences suggesting that loss of LXN in mice improves HFD-induced metabolic dysfunction.

Discussion

Here, we investigated the role of LXN in adipocytes differentiation and metabolic disorders in mice with diet-induced obesity. We found that LXN is upregulated in adipose tissue of mice by body adiposity, and mice deficient in LXN were protected from HFD-induced obesity. We showed that LXN was upregulated during adipocytes differentiation, and LXN deficiency resulted in the reduction of adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells and primary preadipocytes induced by differentiation medium. Mechanistically, we show that mTOR/RXR/PPARɤ signaling pathway mediated the increase of LXN during adipocytes differentiation. LXN deficiency in preadipocyte decreases PPARɤ protein level by enhancing FABP4 mediated ubiquitination and ultimately attenuates adipocyte differentiation and lipogenesis. Importantly, we reveal that LXN deficiency in mice improves obesity-associated liver steatosis, glucose tolerance and insulin resistance, indicating the potential benefits of LXN deficiency in the diet-induced pathogenesis of obesity and obesity-associated metabolic syndrome (Fig S2).

Adipocyte differentiation from adipose precursor cells has been shown to be regulated by mTOR and PPARɤ signaling pathway [12, 28, 29]. The involvement of mTOR signaling in adipogenesis and lipid metabolism has been well recognized in recent years [33]. In particular, a positive role of mTOR in adipogenesis has long been implicated by rapamycin inhibition of preadipocyte differentiation [34,35,36], and activation of PPARγ ameliorated the differentiation deficiency of the mTOR-null adipocytes [37]. We found that the upregulation of LXN in DM-induced preadipocytes were markedly inhibited by mTOR inhibitor rapamycin or PPARɤ inhibitor GW9662, suggesting mTOR and PPARɤ are responsible for regulating LXN expression during preadipocyte differentiation. Retinoic acid has been reported to induce LXN expression through RXR [23, 38]. In adipocytes, PPARγ functions as an obligate heterodimer with RXRs, which participates in the expression of genes related to adipocyte differentiation and lipogenesis [30, 39, 40]. RXR agonists has been reported to enhance the activity of PPARγ-RXR signaling pathway in vivo [41, 42]. We also found that the increased LXN by mTOR agonist 3BDO was reversed when RXRα antagonists PA452 present. Moreover, transcription factor binding sites analysis and ChIP experiments showed that there were PPARɤ or PPARɤ:RXRa binding sites in LXN promoter region. It can thus be convinced that activation of mTOR/RXR/PPARɤ signaling pathway might contribute to elevated LXN expression during adipocyte differentiation.

The expression of PPARγ not only is induced early during adipocyte differentiation but also continues at a high level in mature adipocytes suggests that PPARγ also have important functions in fully differentiated cells [29, 39]. Actually, the level of PPARɤ is tightly regulated during adipocyte differentiation. For example, Garin–Shkolnik et al. reported that PPARɤ induces FABP4 expression in adipocytes, while excessive FABP4 triggers proteasomal degradation of PPARɤ creating a negative feedback loop, which in turn inhibits PPARɤ functions and consequently reduces adipocyte differentiation [32]. Therefore, the net effect of FABP4 seems to be to inhibit PPARɤ [43, 44]. Our data show that LXN deletion in preadipocytes decreased PPARɤ protein level at basal and DM condition, but significantly increased FABP4 protein level accordingly. It is worthy of note that the decrease in PPARɤ protein caused by LXN deficiency was attenuated by FABP4 inhibitors BMS. Importantly, it seems that LXN regulates PPARɤ expression at the protein level rather than at the mRNA level, because LXN deficiency in preadipocyte increases the mRNA level of FABP4, however, has no effect on that of PPARɤ. Therefore, we speculate that LXN regulates the expression of FABP4 through an unknown way, thereby regulating the stability of PPARɤ.

The stability of PPARɤ in WT and LXN-/- preadipocytes was assessed. We confirmed that LXN-/- preadipocytes displayed decreased half-life of PPARɤ, while overexpression of LXN increased its stability. In line with this observation, the PPARɤ ubiquitination has been noted to be increased in LXN knockout 3T3-L1 cells, while FABP4 inhibitor BMS attenuates this effect. Altogether, these findings demonstrate a critical role of PPARɤ/RXR/LXN axis in adipocytes differentiation, and reveal that LXN deletion decreases the protein level of PPARɤ in adipocyte through enhancing FABP4 mediated ubiquitination. FABP4 was identified as a cytosolic protein strongly upregulated during differentiation of preadipocytes into adipocytes [45, 46]. As a marker for adipocyte differentiation, FABP4 expression is specifically induced by insulin and/or IGF-1 [47], dexamethasone and fatty acids [48], and occurs as a downstream target of PPARγ activation [49]. We found that LXN deletion decreased the level of PPARɤ protein, but significantly increased the expression of FABP4 both at mRNA and protein levels. These findings indicate that LXN regulates FABP4 expression at least partially is PPARɤ independent, however, the cause by which LXN attenuates FABP4 expression is currently unknown, and this work is being carried out in our laboratory.

In summary, we demonstrated evidence, for the first time, that LXN functions as a regulator of adipocytes differentiation and adipogenesis. LXN positively regulates PPARɤ stability by inhibiting FABP4 mediated ubiquitination. Therefore, loss of LXN attenuates adipocyte differentiation, lipogenesis, and thus provides protection for mice against HFD-induced obesity and metabolic dysfunction, which may lead to new insights on diet-induced obesity and identify LXN as a potential target for the treatment of obesity and its associated disorders.

Materials and methods

Materials and Methods are available in the online-only Data Supplement.

Data availability

The data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:254–66.

Piche ME, Tchernof A, Despres JP. Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Circulation Res. 2020;126:1477–1500.

Global BMIMC, Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju Sh N, Wormser D, Gao P, Kaptoge S, et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet. 2016;388:776–86.

Collaborators GBDO, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:13–27.

Cinti S. The adipose organ. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, Essent Fat acids. 2005;73:9–15.

Ghaben AL, Scherer PE. Adipogenesis and metabolic health. Nat Rev Mol cell Biol. 2019;20:242–58.

Cristancho AG, Lazar MA. Forming functional fat: a growing understanding of adipocyte differentiation. Nat Rev Mol cell Biol. 2011;12:722–34.

Rodeheffer MS, Birsoy K, Friedman JM. Identification of white adipocyte progenitor cells in vivo. Cell. 2008;135:240–9.

Plikus MV, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Ito M, Li YR, Dedhia PH, Zheng Y, et al. Regeneration of fat cells from myofibroblasts during wound healing. Science. 2017;355:748–52.

Tseng YH, Kokkotou E, Schulz TJ, Huang TL, Winnay JN, Taniguchi CM, et al. New role of bone morphogenetic protein 7 in brown adipogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature. 2008;454:1000–4.

Guntur KV, Guilherme A, Xue L, Chawla A, Czech MP. Map4k4 negatively regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma protein translation by suppressing the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway in cultured adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6595–603.

Minard AY, Tan SX, Yang P, Fazakerley DJ, Domanova W, Parker BL, et al. mTORC1 is a major regulatory node in the FGF21 signaling network in adipocytes. Cell Rep. 2016;17:29–36.

Tontonoz P, Hu E, Graves RA, Budavari AI, Spiegelman BM. mPPAR gamma 2: tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1224–34.

Spiegelman BM. PPAR-gamma: adipogenic regulator and thiazolidinedione receptor. Diabetes. 1998;47:507–14.

Lehrke M, Lazar MA. The many faces of PPARgamma. Cell. 2005;123:993–9.

Mota de Sa P, Richard AJ, Hang H, Stephens JM. Transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis. Compr Physiol. 2017;7:635–74.

Arimatsu Y. Latexin: a molecular marker for regional specification in the neocortex. Neurosci Res. 1994;20:131–5.

Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–31.

Liang Y, Jansen M, Aronow B, Geiger H, Van Zant G. The quantitative trait gene latexin influences the size of the hematopoietic stem cell population in mice. Nat Genet. 2007;39:178–88.

Zhang C, Liang Y. Latexin and hematopoiesis. Current opinion in hematology 2018.

Liu T, Gao Y, Sakamoto K, Minamizato T, Furukawa K, Tsukazaki T, et al. BMP-2 promotes differentiation of osteoblasts and chondroblasts in Runx2-deficient cell lines. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:728–35.

Kadouchi I, Sakamoto K, Tangjiao L, Murakami T, Kobayashi E, Hoshino Y, et al. Latexin is involved in bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced chondrocyte differentiation. Biochemical biophysical Res Commun. 2009;378:600–4.

Oldridge EE, Walker HF, Stower MJ, Simms MS, Mann VM, Collins AT, et al. Retinoic acid represses invasion and stem cell phenotype by induction of the metastasis suppressors RARRES1 and LXN. Oncogenesis. 2013;2:e45.

Zhuang LN, Hu WX, Xin SM, Zhao J, Pei G. Beta-arrestin-1 protein represses adipogenesis and inflammatory responses through its interaction with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARgamma). J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28403–13.

Park HS, Ju UI, Park JW, Song JY, Shin DH, Lee KH, et al. PPARgamma neddylation essential for adipogenesis is a potential target for treating obesity. Cell death Differ. 2016;23:1296–311.

Christianson JL, Nicoloro S, Straubhaar J, Czech MP. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 2 is required for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression and adipogenesis in cultured 3T3-L1 cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2906–16.

Castro-Mondragon JA, Riudavets-Puig R, Rauluseviciute I, Berhanu Lemma R, Turchi L, Blanc-Mathieu R, et al. JASPAR 2022: the 9th release of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic acids res. 2022;50:D165–D173.

Siersbaek R, Nielsen R, Mandrup S. PPARgamma in adipocyte differentiation and metabolism-novel insights from genome-wide studies. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3242–9.

Chawla A, Schwarz EJ, Dimaculangan DD, Lazar MA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma: adipose-predominant expression and induction early in adipocyte differentiation. Endocrinology. 1994;135:798–800.

Tontonoz P, Graves RA, Budavari AI, Erdjument-Bromage H, Lui M, Hu E, et al. Adipocyte-specific transcription factor ARF6 is a heterodimeric complex of two nuclear hormone receptors, PPAR gamma and RXR alpha. Nucleic acids Res. 1994;22:5628–34.

Furuhashi M, Hotamisligil GS. Fatty acid-binding proteins: role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:489–503.

Garin-Shkolnik T, Rudich A, Hotamisligil GS, Rubinstein M. FABP4 attenuates PPARgamma and adipogenesis and is inversely correlated with PPARgamma in adipose tissues. Diabetes. 2014;63:900–11.

Laplante M, Sabatini DM. An emerging role of mTOR in lipid biosynthesis. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R1046–1052.

Yeh WC, Bierer BE, McKnight SL. Rapamycin inhibits clonal expansion and adipogenic differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11086–90.

Bell A, Grunder L, Sorisky A. Rapamycin inhibits human adipocyte differentiation in primary culture. Obes Res. 2000;8:249–54.

Gagnon A, Lau S, Sorisky A. Rapamycin-sensitive phase of 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation after clonal expansion. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189:14–22.

Shan T, Zhang P, Jiang Q, Xiong Y, Wang Y, Kuang S. Adipocyte-specific deletion of mTOR inhibits adipose tissue development and causes insulin resistance in mice. Diabetologia. 2016;59:1995–2004.

Li Y, Huang B, Yang H, Kan S, Yao Y, Liu X, et al. Latexin deficiency in mice up-regulates inflammation and aggravates colitis through HECTD1/Rps3/NF-kappaB pathway. Sci Rep. 2020;10:9868.

Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:289–312.

Lefterova MI, Haakonsson AK, Lazar MA, Mandrup S. PPARgamma and the global map of adipogenesis and beyond. Trends Endocrinol Metab: TEM. 2014;25:293–302.

Nishimaki-Mogami T, Tamehiro N, Sato Y, Okuhira K, Sai K, Kagechika H, et al. The RXR agonists PA024 and HX630 have different abilities to activate LXR/RXR and to induce ABCA1 expression in macrophage cell lines. Biochemical Pharmacol. 2008;76:1006–13.

Mukherjee R, Davies PJ, Crombie DL, Bischoff ED, Cesario RM, Jow L, et al. Sensitization of diabetic and obese mice to insulin by retinoid X receptor agonists. Nature. 1997;386:407–10.

Shum BO, Mackay CR, Gorgun CZ, Frost MJ, Kumar RK, Hotamisligil GS, et al. The adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein aP2 is required in allergic airway inflammation. J Clin Investig. 2006;116:2183–92.

Shaughnessy S, Smith ER, Kodukula S, Storch J, Fried SK. Adipocyte metabolism in adipocyte fatty acid binding protein knockout mice (aP2-/-) after short-term high-fat feeding: functional compensation by the keratinocyte [correction of keritinocyte] fatty acid binding protein. Diabetes. 2000;49:904–11.

Spiegelman BM, Green H. Control of specific protein biosynthesis during the adipose conversion of 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:8811–8.

Bernlohr DA, Angus CW, Lane MD, Bolanowski MA, Kelly TJ Jr. Expression of specific mRNAs during adipose differentiation: identification of an mRNA encoding a homologue of myelin P2 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5468–72.

Blake WL, Clarke SD. Induction of adipose fatty acid binding protein (a-FABP) by insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Biochemical biophysical Res Commun. 1990;173:87–91.

Amri EZ, Ailhaud G, Grimaldi P. Regulation of adipose cell differentiation. II. Kinetics of induction of the aP2 gene by fatty acids and modulation by dexamethasone. J lipid Res. 1991;32:1457–63.

Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79:1147–56.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for technical support by Laboratory Animal Center at Guangxi Normal University.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (No.31660242, 81770310, 32060157, 82104496); Natural Science Foundation Grant Guangxi (No. 2017GXNSFFA198003); Guangdong Foundation for Basic and Applied Basic Research (2020B1515120003); The Open Research Funds of State Key Laboratory of Proteomics (SKLP-O201803).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC and HL supervised the project, contributed to discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. SK, YT, RL and FY\ performed experiments, conducted data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. LW, LZ, XS, SX, XC and YY performed experiments and edited the manuscript. WS, HW and Z-FC contributed to discussion.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Edited by Alessandro Finazzi-Agrò

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kan, S., Li, R., Tan, Y. et al. Latexin deficiency attenuates adipocyte differentiation and protects mice against obesity and metabolic disorders induced by high-fat diet. Cell Death Dis 13, 175 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-04636-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-04636-9

This article is cited by

-

Pancreatic cancer stemness: dynamic status in malignant progression

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2023)

-

Loss of LXN promotes macrophage M2 polarization and PD-L2 expression contributing cancer immune-escape in mice

Cell Death Discovery (2022)