Abstract

Pyroptosis, a form of programmed cell death (PCD), has garnered increasing attention as it relates to innate immunity and diseases. However, the involvement of pyroptosis in the mechanism by which lobaplatin acts against colorectal cancer (CRC) is unclear. Our study revealed that treatment with lobaplatin reduced the viability of HT-29 and HCT116 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Morphologically, HT-29 and HCT116 cells treated with lobaplatin exhibited microscopic features of cell swelling and large bubbles emerging from the plasma membrane, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed multiple pores in the membrane. GSDME, rather than GSDMD, was cleaved in lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis in HT-29 and HCT116 cells due to caspase-3 activation. Knocking out GSDME switched lobaplatin-induced cell death from pyroptosis to apoptosis but did not affect lobaplatin-mediated inhibition of growth and tumour formation of HT-29 and HCT116 cells in vivo and in vitro. Further investigation indicates that lobaplatin induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) elevation and JNK phosphorylation. NAC, a ROS scavenger, completely reversed the pyroptosis of lobaplatin-treated HT-29 and HCT116 and JNK phosphorylation. Activated JNK recruited Bax to mitochondria, and thereby stimulated cytochrome c release to cytosol, followed by caspase-3/-9 cleavage and pyroptosis induction. Therefore, in colon cancer cells, GSDME mediates lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis downstream of the ROS/JNK/Bax-mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and caspase-3/-9 activation. Our study indicated that GSDME-dependent pyroptosis is an unrecognized mechanism by which lobaplatin eradicates neoplastic cells, which may have important implications for the clinical application of anticancer therapeutics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies, whose incidence rate ranks as the fourth leading cause of cancer death1. With the ageing of the population, the changes in the lifestyle and the deterioration of the environment, the incidence of CRC in China has increased year after year and has become one of the most serious malignancies2. However, most CRC patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage and cannot undergo surgery as a treatment3. Thus, chemotherapy is an important part of the comprehensive treatment for advanced CRC4. However, the overall response rate of chemotherapy in CRC patients is unsatisfactory and concurrent with a high incidence of adverse effects5,6. Therefore, the precise mechanism by which chemotherapy combats CRC requires further elucidation.

Pyroptosis, a form of programmed cell death (PCD), was discovered in recent years and is characterized by cell swelling and large bubbles emerging from the plasma membrane7. The pyroptotic cells release interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18), which recruit inflammatory cells and expand the inflammatory response8. Therefore, pyroptosis is inflammation-mediated cell death, which is essentially different from apoptosis9, a non-inflammatory form of PCD. Pyroptosis was initially believed to be a general innate immune response in vertebrates7. Later, the involvement of pyroptosis was observed in multiple pathophysiological processes and diseases, including atherosclerosis10, epilepsy11, Alzheimer’s disease12 and HIV-1 infection13. Caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of HIV by causing CD4+ T-cell depletion13, and pyroptosis-induced activation of the NLRP1 inflammasome is the leading cause of anthrax toxin-mediated lung injury14. Furthermore, Tan et al. demonstrated that NLRP1 inflammasome-induced pyroptosis is involved in symptoms relating to Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy-induced neurodegeneration11,12. Exploring the role of pyroptosis in the pathogenesis of human diseases may provide new ideas and effective therapeutic targets for disease prevention and treatment.

Pyroptosis is mainly stimulated by the activation of the canonical inflammatory caspase-115 and non-canonical caspase-11 (caspase-4/-5 in humans)16,17. In canonical inflammasomes, the assembled NLRP3, NLRC4, AIM2, and Pyrin proteins activate and cleave pro-caspase-1 to form active caspase-118. The latter can cleave gasdermin D (GSDMD) into the N-terminal and C-terminal fragments. The N-terminus of GSDMD translocates to the membrane and mediate perforation, which leads to extracellular content infiltration, cell swelling and then pyroptosis19. In non-canonical inflammasomes, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can directly bind to caspase-4/-5/-1120. On one hand, active caspase-4/-5/-11 can cleave GSDMD, which mediates cell membrane lysis and cell pyroptosis8, and stimulate the NLRP3 inflammasome to activate caspase-1, which produces IL-1β and contributes to its release21. On the other hand, active caspase-4/5/11 activates pannexin-1 to cause ATP release, which then causes opening of the membrane channel P2X7, leading to the formation of small pores on the cell membrane and subsequent pyroptosis. Activated Pannexin-1 also activates the NLRP3 inflammasome through K+ efflux and ultimately leads to IL-1β production and release22.

GSDME/DFNA5 (deafness, autosomal dominant 5), a gene associated with autosomal dominant nonsyndromic deafness23, was newly identified as a promoter of pyroptosis owing to its cleavage by caspase-324. As a member of the gasdermin superfamily, GSDME shares 28% identity with the region of the pore-forming domain of GSDMD24. Genetic mutations within intron 7 of the human GSDME gene led to the skipping of exon 8 and the translation of a C-terminally truncated protein, causing hearing loss25. Recently, the role of GSDME in the pathogenesis of human malignancies has attracted increasing attention. GSDME inactivation due to hypermethylation of the promoter was detected in 50% of primary gastric cancers and supports the notion of GSDME as a putative tumour suppressor26. Moreover, loss of GSDME has been associated with resistance to etoposide in melanoma cells27. Masuda et al. reported that GSDME can be transcriptionally activated by p53 in response to DNA damage caused by etoposide28. These studies indicated that the absence of GSDME in tumours might trigger drug resistance.

Lobaplatin (chemical formula: C9H18N2O3Pt), a third-generation platinum anti-neoplastic agent, exerts stronger anti-neoplastic effects with fewer adverse effects. Nowadays, there are a few studies focused on the effect of lobaplatin on human cancer worldwide29,30,31. However, the inflammatory features of lobaplatin in cancer therapy has not ever reported. In the present study, the type of cell death induced in lobaplatin-treated HT-29 and HCT116 cells was investigated. Moreover, the role of GSDME in cell death was further determined. Finally, the mechanism underlying the cleavage of GSDME was explored. Our study aimed to offer new insights into the mechanism by which lobaplatin mediates cell death in CRC.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures

HT-29 and HCT116 cells (Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and incubated at 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Once the cells reached 70% confluency, they were incubated in the presence or absence of the caspase-3 specific inhibitor zDEVD-FMK (20 µM, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), the caspase-1 specific inhibitor Z-YVAD-FMK (10 µM, abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), the RIPK3 inhibitor GSK’872 (2 µM, Aobious, Gloucester, MA, USA), the Reactive oxygen species (ROS) inhibitor NAC (5 mM, abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) or the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (40 µM, sellerk, Houston, TX, USA), for 3 h and then treated with different doses of lobaplatin for 8 h.

CRISPR-Cas9 knockout and siRNA knockdown

The px458-GSDME-KO plasmid was constructed as previously described32 and stored in our laboratory. HT-29 and HCT116 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well in six-well plates and transfected with 2 µg of px458-GSDME-KO plasmid by Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After 48 h, cells with stable GFP expression were sorted by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences FACS Aria II), and single cells were seeded in a 96-well plate. After 2–3 weeks, each unique clone was tested for GSDME expression by western blotting analysis.

The lentiviral GSDMD-shRNA vectors and their control vectors were constructed and prepared by GeneChem Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All transfections were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For siRNA knockdown, HT-29 and HCT116 cells were plated in six-well plates (1 × 105 per well). After 24 h, 2 µg of NLRP3 (Genepharma, shanghai, China), caspase-1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, 105278), caspase-3 (Invitrogen, 105090), caspase-6 (Invitrogen, 105021), caspase-7 (Invitrogen, 105279), caspase-9 (Invitrogen, 105024) or control siRNA (Invitrogen, 4404020) was transfected with RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 72 h, transfected HT-29 and HCT116 cells were treated with lobaplatin and subjected to subsequent analyses.

Cell viability assays

HT-29 and HT116 cells were seeded into 96-well culture plates with 3000 cells/well and treated with different doses of lobaplatin for 8 h. Cell viability was examined using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay (CCK8, Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Apoptosis evaluation by flow cytometry and tunnel

HT-29 and HT116 cells transfected with the px458-GSDME-KO plasmid were treated with different doses of lobaplatin for 8 h. For flow cytometry detection. Cells were collected by trypsinisation and washed twice with a phosphate-based buffer. Then cells were labelled with annexin V-PE and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Apoptosis was assessed with flow cytometry (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Each experiment was repeated three times. For tunnel analysis, visualized apoptotic cells were labeled with the In Situ Apoptosis Detection kit (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) to detected positive ratio of terminal deoxytransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labelling (TUNEL) following to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized by the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan). Real-time PCR was conducted on an IQ5 instrument (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) using SYBR Green fluorescence signal detection assays (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan) with primers (Table 1). The specific mRNA expression level was quantified by using the 2−∆∆CT method.

Protein extraction and western blot

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Heart, Xi’an, China), and 50 μg of total protein from each lysate was then subjected to SDS-PAGE (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), followed by transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies targeting NLRP3, ASC, IL-1β, GSDMD, GSDME, caspase-1/-3/-6/-7/-9, Bax, Bcl-2, JNK, p-JNK, Hsp60 and GAPDH (all 1:1000 dilution) at 4 °C overnight. The membrane was then washed four times with TBST buffer for 8 min per wash and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Chemiluminescent Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) was added to visualize the protein bands. The antibodies against GAPDH were purchased from Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX, USA), antibodies against NLRP3, ASC, GSDMD, GSDME, and caspase-1/-3/-6/-7/-9 were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA), and antibodies against IL-1β, Bax, Bcl-2 JNK, p-JNK, and Hsp60 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Each experiment was repeated three times.

Measurement of ROS

The ROS levels were measured by a ROS Assay with DCFH-DA (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). After treatment with lobaplatin for 8 h, cells were washed with PBS and stained with DCFH-DA (10 µM) for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. The level of ROS was determined by flow cytometer (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

LDH and IL-1β release assay

LDH and IL-1β were measured using a CytoTox96 LDH-release kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and a QuantiCyto IL-1β ELISA kit (Neobioscience, Chenzhen, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance value at 450 nm was then measured. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Microscopy imaging

To examine the morphology of apoptotic and pyroptotic cells, cells were first seeded in 35-mm culture dishes. Static bright-field images were captured using a Leica XSP-8CA microscope. The pore-forming activity of lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis was examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Nude mouse xenograft assay

The use of all animals in this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. Tumour cells (5 × 106) in the logarithmic growth phase were subcutaneously injected into the right flanks of 4-week-old female BALB/c-nude mice (Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China). At 6 days after cell injection, nude mice were intraperitoneally injected with lobaplatin (11 mg/kg). The length (a) and width (b) of the tumour were monitored every 3 days using callipers. The tumour volume (V) was calculated as follows: V = ab2/2. At the end of the experiment, the mice were sacrificed, and the xenograft tumours were measured. Apoptosis in the xenograft tumours was detected by flow cytometry (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated three times. Data are presented as the means ± SD. Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA was performed to compare the differences among the groups. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Lobaplatin inhibits cell viability and induces pyroptosis in colon cancer cells

To determine the viability of colon cancer cells treated with lobaplatin, HT-29 and HCT116 cells were treated with different doses of lobaplatin for 8 h, and CCK8 assays were performed. Our study showed that treatment with lobaplatin in HT-29 and HCT116 cells inhibited cell viability in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1a). Morphologically, lobaplatin-treated HT-29 and HCT116 cells exhibited large bubbles emerging from the plasma membrane and cell swelling (Fig. 1b, c), which highly resembled the pyroptosis induced by the N-terminus of GSDMD8. TEM revealed multiple pores formed in the membranes of lobaplatin-treated HT-29 and HCT116 cells (Fig. 1d, e). Cells undergoing necroptosis also showed membrane disruption, cell swelling and lysis33. To distinguish pyroptosis from necroptosis, the necroptosis inhibitor GSK’872 was used to block the necroptotic pathway. The results showed that treatment with GSK’872 did not prevent cell death (Supplementary Fig. 1a), indicating that the cell death triggered by lobaplatin in our study is not necroptosis. These data suggest that lobaplatin induces pyroptosis in HT-29 and HCT116 cells.

HT-29 and HCT116 cells were treated with different doses (0, 8, 16 and 32 μg/ml) of lobaplatin for 8 h. Cell viability was then determined using the CCK8 assay (a). Representative bright-field (b, c) and transmission electron microscopy (d, e) images of HT-29 and HCT116 cells treated with 16 μg/ml lobaplatin for 8 h. Red arrowheads indicate the large bubbles emerging from the plasma membrane. Scale bar 50 μm. The release of LDH and IL-1β from lobaplatin-treated HT-29 and HCT116 cells was measured by ELISA (f). All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

Moreover, the release of proinflammatory factors, including IL-1β and LDH, was elevated in lobaplatin-treated HT-29 and HCT116 cells, indicating plasma membrane rupture and leakage (Fig. 1f). The release of IL-1β in pyroptosis requires two signalling of NLRP3 inflammasome: one that upregulates the mRNA of IL-1β and other components (Signal 1) and the other that induces NLPR3 inflammasome activation (Signal 2)34. Teatment with lobaplatin did not affect the mRNA level of IL-1β, CASP-1, ASC, and NLRP3 in HT-29 and HCT116 cells (Fig. 2a, b). We next determined whether lobaplatin activates signal 2 of the NLRP3 inflammasome in HT-29 and HCT116 cells. Lobaplatin promoted the release of IL-1β but did not influence the protein of NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1 (cleaved and pro) and pro-IL-1β (mature and pro)(Fig. 2c, d). Furthermore, Z-YVAD-FMK, an inhibitor of caspase-1, or knockdown of NLPR3 (Supplementary Fig. 6a), failed to reverse the release of IL-1β and LDH induced by lobaplatin (Fig. 2e–h). Therefore, lobaplatin induced mature IL-1β release independent of both signal 1 and 2 of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and it is likely that other mechanism may contribute to the effect.

The mRNA levels of IL-1β, CASP-1, ASC and NLRP3 in HT-29 (a) and HCT116 (b) cells treated with lobaplatin (16 μg/ml) for 8 h was detected by qRT-PCR. Supernatants (SN) and cell extracts (Lysate) were analyzed by western blotting analysis (c, d). ELISA for IL-1β and LDH release of HT-29 (e, f) and HCT116 (g, h) cells treated with lobaplatin in the presence or absence of Z-YVAD-FMK or siRNA-NLPR3 transfection. All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

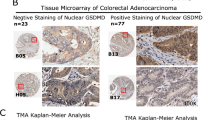

GSDME but not GSDMD is cleaved in lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis in colon cancer cells by activated caspase-3

Recently, pyroptosis was shown to be triggered by the N-terminal domain of GSDMD due to cleavage by caspase-1/-4/-5/-118. GSDMD were high-expressed in HT-29, HCT116, and Caco-2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Our study showed that no cleavage of GSDMD was observed in lobaplatin-treated HT-29 and HCT116 cells (Fig. 3a, b). Furthermore, knockdown of GSDMD (Supplementary Fig. 6b) did not affect the release of IL-1β and LDH (Fig. 3c, d). Therefore, GSDMD is not involved in lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis in HT-29 and HCT116 cells.

Gel images of GSDMD-C terminus (GSDMD-C) in HT-29 and HCT116 cells treated with different doses (0, 8, 16 and 32 μg/ml) of lobaplatin (a, b). ELISA for IL-1β (c) and LDH (d) release of HT-29 and HCT116 cells treated with lobaplatin in the presence or absence of GSDMD knockdown. Gel images of GSDME-N in HT-29 (e) and HCT116 (f) cells treated with different doses (0, 8, 16 and 32 μg/ml) of lobaplatin. Gel images of pro-caspase-3/6/7 and cleaved-caspase-3/6/7 in HT-29 (g) and HCT116 (h) cells treated with of lobaplatin (16 μg/ml). All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

Because the pyroptotic gasdermin N-terminus is shared by all gasdermins except for DFNB5919, we hypothesized that other GSDMD-related family members can trigger pyroptosis. GSDME has been shown to execute pyroptosis under intrinsic and extrinsic stimulus owing to cleavage by caspase-324. The protein levels of GSDME were high in HT-29 and HCT116 cells but absent in Caco-2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Our study found that lobaplatin treatment led to the elevated levels of the N-terminal fragment of GSDME in HT-29 and HCT116 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3e, f). GSK’872 did not inhibit the generation of the N-terminal fragment of GSDME (Supplementary Fig. 1b and c), further confirming that the cell death triggered by lobaplatin in our study is pyroptosis. Taken together, these results indicated that GSDME is cleaved in lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis in colon cancer cells.

Furthermore, the levels of active caspase-3/-6/-7 were elevated in response to lobaplatin treatment (Fig. 3g, h), indicating that GSDME may be cleaved by the active caspase. To verify the involvement of caspase in lobaplatin-triggered pyroptosis, we employed siRNA technology to knock down the expression of caspase-1/-3/-6/-7 in HT-29 and HCT116 cells (Supplementary Fig. 6c). We found that caspase-1/-6/-7 knockdown did not affect the lobaplatin-induced cleavage of GSDME (Fig. 4a, b). However, caspase-3 knockdown suppressed the generation of the N-terminal fragment of GSDME. The release of LDH and IL-1β was markedly decreased upon caspase-3 knockdown (Fig. 4c–f) but was not changed upon caspase-1/-6/-7 knockdown. The pyroptotic morphological features were abrogated in HT-29 and HCT116 cells with caspase-3 knockdown (Fig. 4g, h). Furthermore, HT-29 and HCT116 cells were pre-treated with the caspase-3-specific inhibitor zDEVD-FMK and then treated with lobaplatin. We found that zDEVD-FMK treatment inhibited the cleavage of GSDME (Fig. 5a, b) and the release of LDH and IL-1β (Fig. 5c–f) triggered by lobaplatin.

HT-29 and HCT116 cells were transfected with siRNA targeting CASP-1/-3/-6/-7 or control siRNA and then treated with lobaplatin (16 μg/ml) at 8 h after transfection. GSDME-N terminus were detected by western blot. Gel images of GSDME-N in HT-29 (a) and HCT116 (b) cells. The release of LDH and IL-1β from lobaplatin-treated HT-29 (c, d) and HCT116 (e, f) cells was measured by ELISA. Representative bright-field microscopy images of HT-29 (g) and HCT116 (h) cells treated with lobaplatin in the presence or absence of siRNA-CASP-3 transfecton. Red arrowheads indicate large bubbles emerging from the plasma membrane. Scale bar 50 μm. All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

Gel images of GSDME-F and GSDME-N expression levels in each group of HT-29 (a) and HCT116 (b) cells treated with lobaplatin in the presence or absence of zDEVD-FMK (30 µM). The release of LDH and IL-1β and from HT-29 (c, d) and HCT116 (e, f) cells was measured by ELISA. All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

To investigate the critical role of GSDME in pyroptosis, Caco-2 cells with deficient GSDME were treated with lobaplatin. As expected, Caco-2 underwent apoptosis but not pyroptosis in response to lobaplatin (Supplementary Fig. 2c). The nature of cell death was confirmed by the low percentage of annexin V and 7-AAD double-positive cells and the low levels or released LDH and IL-1β (Supplementary Fig. 2d and e).

To test whether GSDME-dependent pyroptosis induction is a general mechanism, HT-29 and HCT116 cells were treated with LPS, which were reported to induce pyroptosis8. Our study found that treatment with LPS in HT-29 and HCT116 cells induced the typical morphology of pyroptosis and the release of LDH and IL-1β (Supplementary Fig. 3a–d). However, GSDMD but not GSDME was cleaved in HT-29 and HCT116 treated with LPS (Supplementary Fig. 3e and f). Furthermore, the level of cleaved caspase-1 was elevated in response to LPS. These data indicated that GSDME-mediated pyroptosis induced by lobaplatin is specific.

In summary, these data indicated that GSDME rather than GSDMD is cleaved in lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis in colon cancer cells and that the cleavage of GSDME is due to caspase-3 activation.

Knocking out GSDME switches lobaplatin-induced cell death from pyroptosis to apoptosis in vitro

The abovementioned results demonstrated that GSDME is cleaved in lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis in colon cancer cells. Thus, we aimed to investigate whether GSDME is essential for lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis in colon cancer cells. The expression of GSDME in HT-29 and HCT116 cells was knocked out using CRISPR-Cas9 technology (Fig. 6a, b). Western blotting analysis showed that the N-terminal fragment of GSDME was barely detected in GSDME-knockout cells treated with lobaplatin (Fig. 6c, d). However, GSDME knockout did not affect the cleavage of caspase-3 compared with the levels observed in wild-type (WT) cells, which further confirmed that GSDME was downstream of activated caspase-3 in lobaplatin-mediated pyroptosis. Intriguingly, unlike the pyroptotic morphology of lobaplatin-treated WT cells, GSDME-knockout cells exhibited shrinking, fragmentation into apoptotic bodies and non-lysis cell death (Fig. 7a, b), indicating that GSDME knockout switches lobaplatin-induced cell death pyroptosis to apoptosis. Furthermore, the results of the flow cytometry analyses confirmed that knockout GSDME led to fewer annexin V and 7-AAD double-positive cells but more annexin V single-positive cells in HT-29 and HCT116 cells treated with lobaplatin (Fig. 7c, d). However, the tunnel analysis showed that knocking out GSDME did not affect the apoptotic character of cell death induced by lobaplatin (Supplementary Fig. 4a and b), for pyroptosis is associated with DNA fragmentation, which is similar to apoptosis35. Intriguingly, knocking out GSDME did not affect the growth of HT-29 and HCT116 cells in the presence of lobaplatin (Fig. 7e, f). In addition, the release of LDH and IL-1β was decreased in GSDME-knockout cells (Fig. 7g–j). Taken together, these data suggest that GSDME is essential for lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis in colon cancer cells and that knocking out GSDME switches lobaplatin-induced cell death from pyroptosis to apoptosis.

Gel images of GSDME expression levels in HT-29 (a) and HCT116 (b) cells transfected with the px458-GSDME-KO plasmid. Gel images of GSDME expression levels in HT-29 (c) and HCT116 (d) cells treated with lobaplatin in the presence or absence of GSDME knockout. All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

Representative bright-field microscopic images of HT-29 (a) and HCT116 (b) cells treated with lobaplatin in the presence or absence of GSDME knockout. Red arrowheads indicate large bubbles emerging from the plasma membrane. Scale bar 50 μm. The percentage of annexin V and 7-AAD double-positive cells in HT-29 (c) and HCT116 (d) was detected by flow cytometry in the WT and GSDME-KO groups. The effect of GSDME knockout on the cell viability of HT-29 (e) and HCT116 (f) cells in the presence of lobaplatin treatment for 8 h was assessed by the CCK8 assay. The release of LDH and IL-1β from HT-29 (g, h) and HCT116 (i, j) cells was measured by ELISA. All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

GSDME is activated by the lobaplatin-elevated ROS/JNK signaling

We sought to explore the underlying molecular mechanism by which GSDME-dependent pyroptosis was triggered upon lobaplatin treatment. Caspase-3 activation can occur via the death receptor pathway or mitochondrial pathway36,37. Lobaplatin has been reported to induce gastric cancer cell apoptosis by activating the ROS-dependent mitochondrial pathway38. ROS, active forms of oxygen, generates as by-products from cellular metabolism39. ROS have been reported to regulate cells apoptosis and autophagy40. However, whether lobaplatin-elevated ROS is linked to pyroptosis has not been reported. Our study found that treatment with lobaplatin boosts ROS level of HT-29 and HCT116 cells (Fig. 8a). NAC, an inhibitor of ROS, markedly inhibits the ROS elevation induced by lobaplatin and thereby attenuated cell death (Fig. 8b). Moreover, NAC abolished the cleaved GSDME, active caspase-3 and the release of LDH and IL-1β (Fig. 8c–f). Therefore, ROS is involved in GSDME-dependent pyroptosis in response to lobaplatin.

The ROS levels of HT-29 and HCT116 cells treated with lobaplatin in the presence or absence of NAC were measured by a ROS Assay (a). The effect of NAC on the cell viability of HT-29 and HCT116 cells in the presence of lobaplatin treatment for 8 h was assessed by the CCK8 assay (b). Gel images of GSDME-N and cleaved CASP-3 in HT-29 (c) and HCT116 (d) cells treated with lobaplatin (16 μg/ml). The release of LDH (e) and IL-1β (f) from HT-29 and HCT116 cells was measured by ELISA. All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

ROS could affect various signaling pathways such as MAPK signalling pathway41. More importantly, JNK, a stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) of the MAPK family, plays a pivotal role in many cellular events, including apoptosis and autophagy42. Our study found that lobaplatin stimulation markedly elevated the phosphorylation of JNK in HT-29 and HCT116 cell (Fig. 9a, b). More importantly, JNK inhibitor, SP600125, effectively abolished the cleaved GSDME, active caspase-3 and the release of LDH and IL-1β (Fig. 9c–f). Therefore, JNK is likely an upstream regulator of GSDME-dependent pyroptosis. Furthermore, JNK inhibitor treatment did not influence the lobaplatin-induced ROS elevation (Fig. 9g). In contrast, lobaplatin-induced phosphorylation of JNK was abolished by the ROS scavengers NAC (Fig. 9h, i). Altogether, JNK, which is a novel downstream factor of ROS, likely senses lobaplatin-elevated ROS signalling, induce pyroptosis via cleavage of GSDME by caspase-3 activation.

Gel images of JNK and p-JNK in HT-29 (a) and HCT116 (b) cells treated with lobaplatin (16 μg/ml). Gel images of GSDME-N and cleaved CASP-3 in HT-29 (c) and HCT116 (d) cells treated with lobaplatin (16 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of SP6000125. The release of LDH (e) and IL-1β (f) from HT-29 and HCT116 cells was measured by ELISA. The ROS levels of HT-29 and HCT116 cells treated with lobaplatin in the presence or absence of SP6000125 were measured by a ROS Assay (g). Gel images of JNK and p-JNK in HT-29 (h) and HCT116 (i) cells treated with lobaplatin (16 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of NAC. All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

GSDME-dependent pyroptosis is downstream of the ROS/JNK/Bax-mitochondrial apoptotic pathway

The ROS/JNK signalling has been reported to be important for Bax-mitochondrial apoptotic pathway43,44. Thus, we investigate whether Bax is involved in lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis via ROS/JNK signalling. Lobaplatin treatment downregulated the protein levels of Bax and upregulated the protein levels of Bcl-2 (Fig. 10a, b), which can be significantly reversed by ROS inhibitor NAC or JNK inhibitor SP600125. To further confirm the role of Bax in lobaplatin-induced cell death, we constructed Bax-EGFR constructs and transfected them into HT-29 and HCT116 cells (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Overexpression of Bax resulted in characteristic pyroptotic phenotype (Fig. 11c) and elevated LDH and IL-1β release (Fig. 11a, b). Western blotting analysis showed that the N-terminal fragment of GSDME, cleaved caspase-3/-9 and the release of cytochrome c were induced in response to Bax overexpression (Fig. 10c, d). Furthermore, GSDME knockout eliminated the pyroptotic morphology and LDH and IL-1β release (Fig. 11a–c) but did not affected the expression of cleaved caspase-3/-9 and cytochrome c (Fig. 10c, d). Caspase-9 is reported to cleave and activate caspase-345. As expected, knockdown of caspase-9 (Supplementary Fig. 6e) led to the blockade of GSDME and caspase-3 cleavage, and LDH and IL-1β release induced by Bax overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d). Taken together, these results showed that GSDME mediates pyroptosis downstream of the ROS/JNK/Bax-mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and caspase-3/-9 activation.

Gel images of Bcl-2 and BAX expression levels in HT-29 (a) and HCT116 (b) cells treated with lobaplatin in the presence or absence of NAC or SP6000125. Gel images of GSDME-N and cleaved CASP-3/-9 expression levels in HT-29 (c) and HCT116 (d) cells transfected with BAX overexpression plasmid in the presence or absence of GSDME knockout. All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

The release of LDH (a) and IL-1β (b) from HT-29 and HCT116 cells transfected with the BAX overexpression plasmid in the presence or absence of GSDME knockout was measured by ELISA. Representative bright-field microscopy images of HT-29 and HCT116 cells transfected with the BAX overexpression plasmid in the presence or absence of GSDME knockout (c). Red arrowheads indicate large bubbles emerging from the plasma membrane. Scale bar, 50 μm. All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using one-way ANOVA

In Caco-2 cells with deficient GSDME expression, overexpression of Bax increased the levels of cleaved caspase-3/-9 (Supplementary Fig. 2f) but failed to induce pyroptosis and LDH and IL-1β release (Supplementary Fig. 2g and h). These data further revealed that GSDME is necessary for Bax-mitochondrial apoptotic pathway- induced pyroptosis.

GSDME knockout did not affect lobaplatin-inhibited tumour formation of colon cancer cells in vivo

To further explore the role of GSDME-mediated pyroptosis in tumour formation upon lobaplatin treatment, GSDME-modified HT-29 cells and their control cells were subcutaneously injected into nude mice. After 4 weeks post-injection, we treated nude mice with lobaplatin via intraperitoneal injection. The results showed that the size and weight of the xenograft tumours in the GSDME-knockout group were comparable to those in the WT group (Fig. 12a–c). Furthermore, flow cytometry analyses showed that GSDME-knockout tumour tissues had a higher percentage of annexin V single-positive cells and fewer annexin V and 7-AAD double-positive cells (Fig. 12d). Consistent with the in vitro result of tunnel analysis, GSDME knockout did not affect the apoptotic character of cell death in tumour tissues treated with lobaplatin (Supplementary Fig. 4c). The release of serum LDH and IL-1β in nude mice was decreased in the GSDME knockout group compared with that in the WT group (Fig. 12e), which indicated that GSDME knockout attenuates the inflammation induced by lobaplatin. Moreover, the release of the N-terminal fragment of GSDME was barely detected in the knockout group (Fig. 12f). However, GSDME knockout did not affect the expression of Bax, Bcl-2 or cleaved caspase-3/-9, indicating that the activity of GSDME in mediating pyroptosis is downstream of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and caspase-3/-9 activation.

Image of xenograft tumours formed by HT-29 cells treated with lobaplatin in the presence or absence of GSDME knockout (a). Tumour growth curves (b) and tumour weights (c) are shown for the HT-29-GSDME-KO and HT-29-WT groups. The percentage of annexin V and 7-AAD double-positive HT-29 cells in the GSDME-KO and WT groups was detected by flow cytometry (d). The release of serum LDH and IL-1β in the GSDME-KO and WT nude mice was measured by ELISA (e). Gel images of GSDME-N, Bcl-2, BAX and cleaved CASP-3/-9 expression levels in the HT-29-GSDME-KO and HT-29-WT groups (f). All the data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. control using Student’s t-test

Taken together, these results suggest that GSDME knockout switches lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis to apoptosis but does not affect tumour formation in colon cancer cells treated with lobaplatin.

Discussion

Pyroptosis was previously referred to as caspase-1-induced monocyte death in response to certain viral or bacterial infections13. Later, the discovery that caspase-4, -5 and -11 induces pyroptosis in non-monocytic cells upon treatment with LPS expanded the concept of pyroptosis and indicates that pyroptosis is not cell type specific46. Recently, Alnemri and his colleagues demonstrated that treatment with certain apoptotic stimuli activated caspase-3 cleaves GSDME and triggers secondary necrosis after apoptosis or pyroptosis24, which challenges a long-standing view that chemotherapy act most potently through stimulating apoptosis. So far, whether pyroptosis is involved in chemotherapy of lobaplatin in CRC remains unclear. In the present study, we demonstrated that lobaplatin induces ROS/JNK signalling to induce the pyroptosis of colon cancer cells via a novel Bax-caspase-GSDME pathway. In colon cancer cells, lobaplatin-elevated ROS caused the phosphorylation of JNK. Activated JNK further enhanced Bax translocation to the mitochondria, consequently activating caspase-3, and ultimately inducing the cleavage of GSDME and pyroptosis of colon cancer cells. Our study shed light on the interrelation between chemotherapy drug and pyroptosis, and proposed a functional role for pyroptosis in antitumour treatment.

Lobaplatin was reported to induce cell death by elevating ROS30. Excessive generation of ROS could interfere with cellular signaling pathways, and JNK also has a pivotal role in many cellular events47. However, the underlying molecular mechanism of the lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis remains unclear. Our study found lobaplatin induced ROS elevation and JNK phosphorylation. NAC, a ROS scavenger, completely reversed the pyroptosis of lobaplatin-treated HT-29 and HCT116 and the JNK phosphorylation. However, ROS generation was not attenuated by the JNK inhibitor, implying that ROS is the proximal event of JNK. Activated JNK recruited Bax to mitochondria, and thereby stimulated cytochrome c release to cytosol, followed by caspase-3 cleavage and pyroptosis induction. ROS often regulate protein functions via oxidation of cysteines48. Zhou et al. found that the outer mitochondrial membrane protein Tom 20 can be oxidated by the ROS elevation, subsequently facilitates Bax recruitment to mitochondria and stimulates caspase-3/GSDME-mediated pyroptosis in response to iron treatment49. Therefore, besides apoptosis and autophagy40, ROS can induce cell death towards pyroptosis pathway. Further study will focus on whether there exists other molecular mechanism of ROS-mediated pyroptosis. From these data, we concluded that lobaplatin induced pyroptosis by Bax-caspase-GSDME pathway via the ROS/JNK signalling.

Necroptosis, a form of programmed necrotic cell death, is activated by a pro-apoptotic stimulus through the receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIPK1)–RIPK3-mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) axis33. Cells undergoing necroptosis also showed membrane disruption, cell swelling and lysis. The cell death triggered by lobaplatin in our study is pyroptosis but not necroptosis, as demonstrated by the following evidence: (1) necroptosis could not be blocked by caspase inhibitors, but the caspase-3-specific inhibitor zDEVD-FMK markedly inhibited lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis, and caspase activation was responsible for pyroptosis; (2) the RIPK3 inhibitors GSK’872 could not influence the lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis of colon cancer cells; (3) GSDME, an pyroptosis executor, was cleaved due to caspase-3 activation in response to iron stimulation, which was linked to pyroptosis induction. Notably, lobaplatin can stimulate different forms of cell due to the activation of different signaling pathways. In addition to pyroptosis, lobaplatin-induced apoptosis and necroptosis have also been reported50.

For a long time, secondary necrosis has been considered as a final phase of PCD following apoptosis completion, indicated by lysis, osmotic cell swelling and the leakage of the cell contents, features that are also common to pyroptosis51. Moreover, secondary necrosis resembles pyroptosis in their ability to deliver potent proinflammatory signals. There exists great divergence between secondary necrosis after apoptosis and pyroptosis. On one hand, Alnemri et al. provide convincing evidence in support of the notion that GSDME-mediated pyroptosis was considered the secondary necrosis, for cleavage of GSDME is downstream of mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and caspase-3 activation24. On the other hand, GSDME-mediated pyroptosis may precede or even impede apoptosis in cells with high GSDME expression, while GSDME-deficient cells favour apoptotic outcomes52. Distinct from these previous conceptions, Lu et al. demonstrated that apoptosis and pyroptosis were contemporaneously instigated by anticancer therapy, considering the biochemical markers for apoptosis and pyroptosis were synchronously detected in drug-treated adherent cells and supernatant cells53. However, drug-treated GSDME knockouts yielded more cleaved PARP and caspase-3 products, which was the hallmark of apoptosis. Our study indicated that knocking out GSDME switches lobaplatin-induced cell death from pyroptosis to apoptosis, supporting that the expression level of GSDME determines the form of cell death in caspase-3-activated cells. Considering the heterogeneity of GSDME expression in tumour tissues53, we argued it was plausible to speculate that apoptosis and pyroptosis were contemporaneously stimulated by chemotherapy. Besides caspase-3–dependent pyroptosis, recent study indicated the apoptotic caspase-8 induces cleavage of GSDME and GSDMD to elicit pyroptosis during Yersinia infection, which implied that pyroptosis and apoptosis share many signal transduction pathways54,55. Further study will be needed to focus on the potential mechanism underlying the transformation between pyroptosis and apoptosis.

Previous study indicated that GSDME expression is generally undetectable in CRC56, gastric cancer26, breast cancer57,58 and hepatocellular carcinoma59 due to epigenetic inactivation. Therefore, whether GSDME-dependent pyroptosis as a universal mechanism of chemotherapy to eradicate neoplastic cells remain controversial. Notably, owing to adoption of in vitro systems or invalidated antibodies, previous studies did not always reflect the actual GSDME level of in vivo tumour. In contrast to previous conclusion that no or little GSDME is expressed in other tumour types, Zhuang et al. found that GSDME was ubiquitously expressed among diverse molecular subtypes of lung cancer53. Therefore, scientifically-sound studies are still needed to explore the expression partner of GSDME in various type of tumours. Interestingly, GSDME-dependent pyroptosis may be involved in chemotherapy drug-induced toxicity. GSDME−/− mice exhibited reduced adverse effects of chemotherapy drugs, including tissue damage (intestine and lung) and weight loss24. The clinical significance of GSDME-dependent pyroptosis in cancer chemotherapy of CRC still requires further investigation.

Whether GSDME-dependent pyroptosis contributes to anti-cancer effects of chemotherapy is determined. In lung cancer, genetic deletion of GSDME promoted drug resistance, while GSDME overexpression led to enhanced drug sensitivity in vivo and in vitro53. Lage et al. reported that GSDME expression was decreased in etoposide-resistant melanoma cells and was negatively associated with cell resistance to etoposide-induced cell death27. Genetic GSDME deletion attenuated drug response and induce more drug-tolerant state. Reversal of GSDME silencing by treatment with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor decitabine may sensitize tumour cells to chemotherapy drugs24. However, our study indicated that knocking out GSDME switches lobaplatin-induced cell death from pyroptosis to apoptosis but does not affect the growth and tumour formation of colon cancer cells treated with lobaplatin. Consistent with these results, knocking out GSDME has no effect on the growth of gastric cancer cells32. There are at least three factor contributing to the notion that the GSDME did not influence on anti-cancer effects of chemotherapy: (1) GSDME levels determines the form of cell death. Either apoptosis or pyroptosis alone was sufficient for driving cell death and modulating GSDME just altered the apoptotic process; (2) in addition to GSDME, other mediator is involved in pyroptosis induction; (3) In the absence of GSDME, other form of cell death may result in eradicating tumour cells. Chemotherapy may trigger different form of programmed cell death (apoptosis, necroptosis or pyroptosis) to synergistically, rather than mutually exclusively, eradicate tumour cells, which remains to be further elucidated.

In conclusion, GSDME mediates pyroptosis downstream of the ROS/JNK/Bax-mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and caspase-3/-9 activation. Our study indicated that GSDME-dependent pyroptosis is an unrecognized mechanism by which lobaplatin eradicates neoplastic cells, which may have important implications for the clinical and optical application of anticancer therapeutics.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67, 7–30 (2017).

Chen, W. et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CACancer J. Clin. 66, 115–132 (2016).

Fahy, B. N. Follow-up after curative resection of colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 21, 738–746 (2014).

Hegewisch-Becker, S. et al. Maintenance strategies after first-line oxaliplatin plus fluoropyrimidine plus bevacizumab for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (AIO 0207): a randomised, non-inferiority, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 16, 1355–1369 (2015).

Turner, N. C. & Reis-Filho, J. S. Genetic heterogeneity and cancer drug resistance. Lancet Oncol. 13, e178–e185 (2012).

Kanterman, J. et al. Adverse immunoregulatory effects of 5FU and CPT11 chemotherapy on myeloid-derived suppressor cells and colorectal cancer outcomes. Cancer Res. 74, 6022–6035 (2014).

Jorgensen, I. & Miao, E. A. Pyroptotic cell death defends against intracellular pathogens. Immunol. Rev. 265, 130–142 (2015).

Shi, J. et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 526, 660–665 (2015).

Campisi, L., Cummings, R. J. & Blander, J. M. Death-defining immune responses after apoptosis. Am. J. Transplant. 14, 1488–1498 (2014).

Duewell, P. et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464, 1357–1361 (2010).

Tan, C. C. et al. NLRP1 inflammasome is activated in patients with medial temporal lobe epilepsy and contributes to neuronal pyroptosis in amygdala kindling-induced rat model. J. Neuroinflamm. 12, 18 (2015).

Tan, M. S. et al. Amyloid-beta induces NLRP1-dependent neuronal pyroptosis in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell death & Dis. 5, e1382 (2014).

Doitsh, G. et al. Cell death by pyroptosis drives CD4 T-cell depletion in HIV-1 infection. Nature 505, 509–514 (2014).

Kovarova, M. et al. NLRP1-dependent pyroptosis leads to acute lung injury and morbidity in mice. J. Immunol. 189, 2006–2016 (2012).

Lamkanfi, M. & Dixit, V. M. Mechanisms and functions of inflammasomes. Cell 157, 1013–1022 (2014).

Shi, J. et al. Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature 514, 187–192 (2014).

Hagar, J. A., Powell, D. A., Aachoui, Y., Ernst, R. K. & Miao, E. A. Cytoplasmic LPS activates caspase-11: implications in TLR4-independent endotoxic shock. Science 341, 1250–1253 (2013).

Latz, E., Xiao, T. S. & Stutz, A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 397–411 (2013).

Ding, J. et al. Pore-forming activity and structural autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature 535, 111–116 (2016).

Khan, M. M. et al. Mass Spectrometry-based Structural Analysis and Systems Immunoproteomics Strategies for Deciphering the Host Response to Endotoxin. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 2641–2660 (2018).

Kayagaki, N. et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479, 117–121 (2011).

Yang, D., He, Y., Munoz-Planillo, R., Liu, Q. & Nunez, G. Caspase-11 requires the pannexin-1 channel and the purinergic P2X7 pore to mediate pyroptosis and endotoxic shock. Immunity 43, 923–932 (2015).

Van Laer, L. et al. Nonsyndromic hearing impairment is associated with a mutation in DFNA5. Nat. Genet. 20, 194–197 (1998).

Rogers, C. et al. Cleavage of DFNA5 by caspase-3 during apoptosis mediates progression to secondary necrotic/pyroptotic cell death. Nat. Commun. 8, 14128 (2017).

Cheng, J. et al. A novel DFNA5 mutation, IVS8+4 A>G, in the splice donor site of intron 8 causes late-onset non-syndromic hearing loss in a Chinese family. Clin. Genet. 72, 471–477 (2007).

Akino, K. et al. Identification of DFNA5 as a target of epigenetic inactivation in gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 98, 88–95 (2007).

Lage, H., Helmbach, H., Grottke, C., Dietel, M. & Schadendorf, D. DFNA5 (ICERE-1) contributes to acquired etoposide resistance in melanoma cells. FEBS Lett. 494, 54–59 (2001).

Masuda, Y. et al. The potential role of DFNA5, a hearing impairment gene, in p53-mediated cellular response to DNA damage. J. Human. Genet. 51, 652–664 (2006).

Wu, X. et al. A randomized and open-label phase II trial reports the efficacy of neoadjuvant lobaplatin in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 9, 832 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Lobaplatin induces BGC-823 human gastric carcinoma cell apoptosis via ROS- mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and impairs cell migration and invasion. Biomed. & pharmacother. 83, 1239–1246 (2016).

Yang, F. et al. Lobaplatin arrests cell cycle progression, induces apoptosis and impairs migration and invasion in B16-F10 melanoma cell line in vitro. Biomed. & pharmacother. 69, 402–408 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. GSDME mediates caspase-3-dependent pyroptosis in gastric cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 495, 1418–1425 (2018).

Wallach, D., Kang, T. B., Dillon, C. P. & Green, D. R. Programmed necrosis in inflammation: Toward identification of the effector molecules. Science 352, aaf2154 (2016).

Hao, H. et al. Farnesoid X receptor regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome underlies cholestasis-associated sepsis. Cell Metab. 25, 856–867.e855 (2017).

Fink, S. L. & Cookson, B. T. Caspase-1-dependent pore formation during pyroptosis leads to osmotic lysis of infected host macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 1812–1825 (2006).

Kale, J., Liu, Q., Leber, B. & Andrews, D. W. Shedding light on apoptosis at subcellular membranes. Cell 151, 1179–1184 (2012).

Julien, O. & Wells, J. A. Caspases and their substrates. Cell death Differ. 24, 1380–1389 (2017).

Yin, C. Y. et al. Lobaplatin inhibits growth of gastric cancer cells by inducing apoptosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 17426–17433 (2014).

Fruehauf, J. P. & Meyskens, F. L. Jr. Reactive oxygen species: a breath of life or death? Clin. Cancer Res. 1, 789–794 (2007).

Li, H. Y. et al. Celastrol induces apoptosis and autophagy via the ROS/JNK signaling pathway in human osteosarcoma cells: an in vitro and in vivo study. Cell death & Dis. 6, e1604 (2015).

Avisetti, D. R., Babu, K. S. & Kalivendi, S. V. Activation of p38/JNK pathway is responsible for embelin induced apoptosis in lung cancer cells: transitional role of reactive oxygen species. PloS ONE 9, e87050 (2014).

Tsujimoto, Y. & Shimizu, S. Another way to die: autophagic programmed cell death. Cell death Differ. 12(Suppl 2), 1528–1534 (2005).

Deng, L. et al. HCV upregulates Bim through the ROS/JNK signalling pathway, leading to Bax-mediated apoptosis. J. General. Virol. 96, 2670–2683 (2015).

Tsuruta, F. et al. JNK promotes Bax translocation to mitochondria through phosphorylation of 14-3-3 proteins. EMBO J. 23, 1889–1899 (2004).

Li, P. et al. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell 91, 479–489 (1997).

Kayagaki, N. et al. Noncanonical inflammasome activation by intracellular LPS independent of TLR4. Science. 341, 1246–1249 (2013).

Shen, H. M. & Liu, Z. G. JNK signaling pathway is a key modulator in cell death mediated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Free Radic. Biol. & Med. 40, 928–939 (2006).

Patel, R. & Sesti, F. Oxidation of ion channels in the aging nervous system. Brain Res. 1639, 174–185 (2016).

Zhou, B., et al. Tom20 senses iron-activated ROS signaling to promote melanoma cell pyroptosis. Cell Res. 28: 1171–1185 (2018).

Engel, J. B. et al. Effects of lobaplatin as a single agent and in combination with TRAIL on the growth of triple-negative p53-mutated breast cancers in vitro. Anti-Cancer Drugs 23, 426–436 (2012).

Vanden Berghe, T. et al. Necroptosis, necrosis and secondary necrosis converge on similar cellular disintegration features. Cell death Differ. 17, 922–930 (2010).

Wang, Y. et al. Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature 547, 99–103 (2017).

Lu, H. et al. Molecular targeted therapies elicit concurrent apoptotic and GSDME-dependent pyroptotic tumor cell death. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 6066–6077 (2018).

Sarhan, J. et al. Caspase-8 induces cleavage of gasdermin D to elicit pyroptosis during Yersinia infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E10888–e10897 (2018).

Orning, P., Weng, D., Starheim, K., Ratner, D. Pathogen blockade of TAK1 triggers caspase-8-dependent cleavage of gasdermin D and cell death. Science. 362, 1064–1069 (2018).

Kim, M. S. et al. Aberrant promoter methylation and tumor suppressive activity of the DFNA5 gene in colorectal carcinoma. Oncogene 27, 3624–3634 (2008).

Croes, L. et al. DFNA5 promoter methylation a marker for breast tumorigenesis. Oncotarget 8, 31948–31958 (2017).

Kim, M. S. et al. Methylation of the DFNA5 increases risk of lymph node metastasis in human breast cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 370, 38–43 (2008).

Wang, C. J. et al. The expression and regulation of DFNA5 in human hepatocellular carcinoma DFNA5 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40, 6525–6531 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Serial Numbers: 81101874, 81172362), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (xjj2018123), the Science and Technology Project of Shaanxi Province (Grant serial number 2016SF-015), the Coordinative and Innovative Plan Projects of the Science and Technology Program in Shaanxi Province (Grant Serial Numbers: 2013KTCQ03-08).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Edited by B. Zhivotovsky

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, J., Li, S., Qi, J. et al. Cleavage of GSDME by caspase-3 determines lobaplatin-induced pyroptosis in colon cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 10, 193 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-019-1441-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-019-1441-4

This article is cited by

-

The application of nanoparticles-based ferroptosis, pyroptosis and autophagy in cancer immunotherapy

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2024)

-

Acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 induces pyroptosis and inflammation of renal epithelial tubular cells in sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by upregulating the KLF5/NF-κB pathway

Cell Communication and Signaling (2024)

-

Melatonin alleviates chronic stress-induced hippocampal microglia pyroptosis and subsequent depression-like behaviors by inhibiting Cathepsin B/NLRP3 signaling pathway in rats

Translational Psychiatry (2024)

-

The gasdermin family: emerging therapeutic targets in diseases

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2024)

-

Diverse functions of cytochrome c in cell death and disease

Cell Death & Differentiation (2024)