Abstract

Tightly orchestrated programmed cell death (PCD) signalling events occur during normal neuronal development in a spatially and temporally restricted manner to establish the neural architecture and shaping the CNS. Abnormalities in PCD signalling cascades, such as apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and cell death associated with autophagy as well as in unprogrammed necrosis can be observed in the pathogenesis of various neurological diseases. These cell deaths can be activated in response to various forms of cellular stress (exerted by intracellular or extracellular stimuli) and inflammatory processes. Aberrant activation of PCD pathways is a common feature in neurodegenerative diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease, resulting in unwanted loss of neuronal cells and function. Conversely, inactivation of PCD is thought to contribute to the development of brain cancers and to impact their response to therapy. For many neurodegenerative diseases and brain cancers current treatment strategies have only modest effect, engendering the need for investigations into the origins of these diseases. With many diseases of the brain displaying aberrations in PCD pathways, it appears that agents that can either inhibit or induce PCD may be critical components of future therapeutic strategies. The development of such therapies will have to be guided by preclinical studies in animal models that faithfully mimic the human disease. In this review, we briefly describe PCD and unprogrammed cell death processes and the roles they play in contributing to neurodegenerative diseases or tumorigenesis in the brain. We also discuss the interplay between distinct cell death signalling cascades and disease pathogenesis and describe pharmacological agents targeting key players in the cell death signalling pathways that have progressed through to clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Programmed cell death (PCD) is required for normal development and maintenance of tissue homoeostasis, and the elimination of damaged, infected or obsolete cells in multicellular organisms. Seminal discoveries by Kerr et al. in 1972 identified the hallmark ultrastructural features of cells undergoing programmed suicide, where the term ‘apoptosis’ was coined for this form of PCD [1]. These features include cytoplasmic shrinkage, nuclear condensation and fragmentation and the formation of apoptotic bodies that are evident in various tissues under physiological or certain pathological conditions. The family of anti- and pro-apoptotic B cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) protein family members has been discovered that regulate this pathway and are comprised of three subgroups based on their structure and function with the presence of conserved regions termed BCL-2 homology (BH) motifs). This includes the anti-apoptotic proteins (BCL-2, BCL-XL, MCL-1, BCL-W and A1/BFL1), the BH3-only proteins (BIM, PUMA, BID, BMF, BAD, HRK, BIK, NOXA), the critical initiators of apoptosis and multi-BH domain proteins (BAX and BAK), the essential effectors of apoptosis that form oligomers that cause mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation (MOMP), thereby releasing apoptogenic factors that promote a cascade of caspase (aspartate-specific cysteine proteases) activation [2, 3]. Upon activation, caspases cleave hundreds of cellular substrates, thereby precipitating the morphological features of apoptosis and demolition of the cell [4,5,6].

Normal development and tissue homoeostasis in multicellular organisms depend on orchestrated PCD signalling events that are tightly regulated. During embryogenesis, the elimination of cells by PCD is necessary for adequate moulding of certain tissues, for example the sculpting of the digits of vertebrate limbs [7]. The central nervous system (CNS), comprised of the brain and spinal cord, is shaped by PCD where signalling events that are tightly regulated at a temporal and spatial level result in establishment of the neural architecture. In normal neural embryonic and post-natal development, apoptosis is the major form of PCD. Apoptosis can affect distinct cell populations, including neural precursor cells (NPCs), differentiated post-mitotic neurons and glial cells, ensuring the survival only of cells that are of the correct size and shape and have made the proper connections with their axons and neurites [8]. In mouse embryos, neurogenesis occurs as early as E12 when NPCs exit the cell cycle and differentiate into post-mitotic neurons. It was shown that the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family members myeloid cell leukaemia-1 (MCL-1) and BCL-2-related gene long isoform (BCL-XL) play critical roles in cell survival during developmental neurogenesis. Neuronal-specific ablation of both proteins resulted in massive apoptotic cell death throughout the entire CNS [9], and even loss of either gene caused fatal defects in the brain [10, 11]. Conversely, the combined absence of BAX, BAK (and their relative BOK) causes an increase of neurons within certain areas of the brain [12], although the impact of this for brain function and behaviour is not known. The critical opposing roles of the pro- and anti-apoptotic members of the BCL-2 family are demonstrated by the observation that the combined loss of one allele of Mcl-1 and one allele of Bclx (Mcl1+/−Bclx+/− mice) causes severe craniofacial abnormalities and early post-natal death, while additional loss of one allele of Bim (Mcl1+/−Bclx+/−Bim+/− mice) prevents these abnormalities completely [13].

While removal of superfluous neuronal cells is vital for normal brain function, aberrant death of distinct neuronal cell populations is a hallmark of pathology associated with neurodegenerative diseases, such as ALS, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease (HD) (reviewed in [14]). Conversely, defects in PCD of neuronal cells or other cell types in the brain is thought to promote development of brain cancers, such as the highly aggressive glioblastoma multiforme [15]. The cell death pathways are associated with distinct morphological and biochemical features (refer to Table 1 for characteristic morphological and biochemical hallmarks, highlighting fundamental differences in the pathways). For example, apoptosis is typically associated with cell shrinkage, while necroptosis involves cell swelling and leakage of cellular contents.

The aetiology of neurodegenerative diseases is multifactorial, being associated with defects in different cellular processes, such as response to oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, protein misfolding (ER stress) and inflammation [16,17,18,19]. Considerable evidence supports a role of cell death in the pathogenesis of various diseases of the brain and peripheral nervous system. Nevertheless, an important question remains whether defects in cell death signalling and neuronal cell death is a primary or only a secondary response to the insults that cause these diseases, and how different PCD pathways and additional processes interact to cause the demise of neuronal cells and other cell types in these pathologies.

In this review, we provide a brief overview of PCD pathways, namely apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis as well as cell death associated with autophagy and unprogrammed necrosis. We discuss their known and proposed roles in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases and brain cancer, such as GBM. We also describe already existing and proposed therapeutic strategies to target central regulators of the various PCD pathways for the treatment of neurological diseases.

Programmed cell death signalling pathways and their roles in neurological diseases

Apoptosis

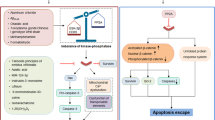

Apoptosis can be triggered by two distinct pathways: the intrinsic (also called mitochondrial or BCL-2-regulated) pathway and the death receptor (also called extrinsic) pathways [20, 21]. The intrinsic pathway is regulated by the pro- and anti-apoptotic members of the BCL-2 protein family. In healthy cells the anti-apoptotic proteins BCL-2, BCL-XL, MCL-1, BCL-W and A1/BFL1 safeguard cell survival by restraining the essential effectors of cell death BAX and BAK [2]. In response to intracellular stress (e.g. growth factor deprivation, DNA damage, ER stress), the BH3-only proteins (BIM, PUMA, BID, BMF, BAD, HRK, BIK, NOXA), the critical initiators of apoptosis, are transcriptionally or post-transcriptionally upregulated [22]. The BH3-only proteins bind with high affinity to anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins, thereby liberating BAX and BAK. Some BH3-only proteins are reported to also activate BAX and BAK directly [2, 3, 23]. Upon activation, BAX and BAK form oligomers that cause MOMP with consequent mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO [21]. These apoptogenic factors promote activation of the caspase cascade, resulting in the cleavage of hundreds of proteins leading to demolition of the cell. The death receptor pathway is activated by ligation of members of the tumour necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily that have an intracellular death domain by their respective ligands (e.g. FAS activated by FAS ligand) [24]. This promotes the formation of an intracellular death inducing signalling complex, resulting in the activation of caspase-8 and the downstream effector caspases (caspases-3 and -7) (Figs. 1 and 2) [25]. The death receptor pathway can connect to the intrinsic apoptotic pathway through caspase-8-mediated proteolytic activation of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein BID (Fig. 1) [24].

Intrinsic apoptosis signalling: in response to growth factor deprivation, DNA damage or oncogene activation, BH3-only pro-apoptotic proteins are induced transcriptionally or post-transcriptionally. The BH3-only proteins bind to and inhibit the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins. This leads to release and activation of the effectors of cell death, BAX and BAK, which then oligomerise and promote mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation (MOMP), leading to release of apoptogenic factors, including cytochrome c and Smac/Diablo. This initiates a cascade of caspase activation, cleavage of hundreds of cellular proteins and consequent cell demolition. Death receptor induced (extrinsic) apoptosis signalling: stimulation of death receptors (members of the TNFR family with an intracellular death domain) by their cognate ligands (e.g. stimulation of FAS by FASL) results in adaptor protein (FADD, TRADD) mediated recruitment and activation of the initiator caspase, caspase-8 (in humans also caspase-10), which can then activate downstream effector caspases (caspases-3, -7), resulting in cell demolition (see above). The death receptor induced apoptosis pathway can connect to the intrinsic apoptotic pathway by proteolytic activation of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein BID (to generate tBID) by caspase-8. Necroptosis: the best characterised pathway triggering necroptosis is via TNFR1 stimulation. Upon binding of TNFα to TNFR1, cIAPs, RIPK1, TRAFs and TRADD are recruited to the intracellular part of TNFR1, forming the TNFR1 signalling complex I, which activates NFkB and AP1 transcription factors and thereby stimulates cell survival and proliferation. Upon deubiquitylation of RIPK1 by CYLD, RIPK1 can bind to TRADD, FADD and caspase-8 forming complex II which can drive caspase-8 mediated apoptosis (see above). In the absence of caspase-8 (genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition) and the absence or inhibition of cIAP1/2, the necrosome (complex III) is formed where RIPK3 can phosphorylate MLKL, promoting its translocation to the plasma membrane where MLKL causes cell lysis, resulting in lytic cell death with release of DAMPs and PAMPs.

Ferroptosis is potentiated by iron which can be imported by TFR1 and DMT1, and requires the presence of susceptible arachidonic acid-containing phospholipids generated by ACSL4 and LPCAT3. Ferroptosis is endogenously inhibited by GPX4 which requires GSH as a substrate, by ubiquinone which is reduced by FSP1, by BH4 which is generated by GCH1, and by other endogenous RTAs such as vitamin E. Ferroptosis is promoted by disruption of cysteine supply via inhibition of the glutamate/cystine antiporter system xCT (by compounds such as erastin, sorafenib, sulfasalazine or glutamate), or impaired GPX4 activity due to insufficient glutathione or selenium or by direct inhibition (e.g. RSL3, ML162, ML210, FIN56, FINO2). Ferroptosis inhibitors include iron chelators (such as deferiprone and deferoxamine), RTAs (including ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1) and lipoxygenase inhibitors. Pyroptosis can be activated in response to physiological or pathological insults which result in activation of inflammasomes, such as the NLRP3 inflammasome, in which the adaptor ASC is recruited, resulting in activation of caspase-1. Caspase-1 proteolytically processes pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into the bio-active forms of these cytokines. Caspase-1 can also cleave GSDMD, and the N‐terminal fragment of GSDMD is recruited to the plasma membrane where it causes pore formation, cell swelling and plasma membrane rupture. BH4 tetrahydrobiopterin, BSO Buthionine sulfoximine, DMT1 divalent metal transporter 1, GCH1 GTP cyclohydrolase-1, GPX4 glutathione peroxidase 4, GSH glutathione, RTAs radical trapping antioxidants, Se selenium, System xCT glutamate/cystine antiporter, TFR1 transferrin receptor 1, NLRP3 NLR family pyrin domain‐containing 3.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive adult-onset form of MND caused by the aberrant death of motor neurons in the cerebral cortex and spinal cord. The resulting motor neuron loss leads to muscle atrophy and weakness, muscle twitches, spasticity and typically death from respiratory failure [26]. Various molecular processes have been associated with this pathology, including oxidative stress, excitotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction [27]. Mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) account for ~20% of familial ALS cases [28]. A direct role for SOD1 in regulating the apoptotic machinery was proposed based on reports that on the surface of mitochondria in cells from the spinal cord mutant SOD1 was bound to BCL-2, with the contention that this would inhibit this anti-apoptotic protein [29]. Moreover, changes in the expression of certain BCL-2 family members and caspases have been observed in the spinal cord of transgenic mice expressing mutant SOD1 and from humans affected with ALS [30]. Abnormally reduced levels of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 have been reported in the SOD1G93A mouse model [31, 32] as well as increased expression of the apoptosis effector BAX in spinal cord motor neurons of ALS patients [33]. Abnormally high mRNA levels of the BH3-only protein BIM were found in the spinal cord of post-symptomatic SOD1G85R transgenic mice and, importantly, BIM deficiency extended the lifespan of SOD1G93A mutant mice [34]. The onset of symptoms and terminal illness were also delayed in SOD1G93A mice by administration of the broad spectrum caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk [35], overexpression of BCL-2 [36] or the absence of the apoptosis effectors BAX and BAK [37].

AD is the leading cause of dementia. Hallmark pathological features of AD include the accumulation of amyloid-β-containing neuritic plaques derived from aggregates produced by sequential cleavages of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), neurofibrillary tangles and dystrophic neurites containing hyperphosphorylated tau [38]. Evidence for a role of apoptosis in neuronal cell death in AD is limited. However, based on immuno-histochemical staining of neurons, it has been proposed that intracellular Aβ can induce apoptosis through p53-dependent transcriptional upregulation of BAX [39, 40] and reductions in BCL-2 and BCL-XL [41]. It was also reported that caspase activation and their cleavage of APP are associated with synapse loss [42,43,44].

HD is characterised by progressive motor, behavioural and cognitive decline. This is driven by expanded CAG repeats in the HTT gene that encodes huntingtin. Observations in mouse models of HD include increased levels of pro-apoptotic BIM and BAX in brain lysates at late stages of the disease [45, 46]. Notably, loss of one allele of Bim significantly attenuated the accumulation of mHTT (mutant Huntington protein), neuronal death and disease-associated phenotypes [47]. BAX expression in the brain was reported to be maximal in grade 2 and 3 HD brains [48].

Degeneration of the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra is the cause of motor dysfunction in PD that is characterised by a resting tremor as well as abnormal posture and gait. In PD, the predominant mechanism of neuronal death is thought to be via the intrinsic apoptosis pathway in dopaminergic neurons. Inherited forms of PD are associated with mutations in genes associated with mitochondrial function, such as PRKN, LRRK2, PINK1 and PARK7 [49]. The functions of the corresponding proteins may intersect with components of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway given that they are both located on the outer mitochondrial membrane. Indeed, Parkin was shown to suppress apoptosis by ubiquitinating BAK, thereby reducing its oligomerisation and apoptotic activity. PD-associated Parkin mutants had reduced ability to ubiquitinate BAK, suggesting that this would cause an increase in BAK-mediated apoptosis [50]. Caspase inhibitors were shown to be neuroprotective in in vitro models of PD [51]. Examination of brain tissue from PD patients revealed abnormally increased levels of active caspase-3 and BAX [52] as well as significant reductions in BCL-2, which correlated inversely with disease duration and severity [53]. These findings suggest that aberrant activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway may contribute to or even be a major driver of neuronal death in PD.

GBM is the most common form of brain cancer in humans with a poor prognosis (5-year survival of only 5%) that is largely due to its invasiveness. GBM cells are resistant to apoptotic stimuli and it is thought that this contributes to the failure of conventional standard of care treatment in this disease. Human glioblastoma cells were shown to express higher levels of BCL-2 and BCL-XL compared to non-neoplastic glial cells [54]. RNA interference mediated reduction in BCL-2 or BCL-XL was able to kill glioblastoma cells in culture, and this death was caspase dependant [54]. Furthermore, high levels of BCL-XL have been reported to be associated with rapid progression and poor survival of glioblastoma patients and BCL-XL has therefore been proposed as a marker of therapy resistance in this malignancy [55].

Necroptosis

Necroptosis is a lytic form of PCD that can drive inflammation. Necroptosis can be induced by the stimulation of TNFR1, TLRs and certain other receptors when the activity of caspase-8 is blocked by pharmacological agents or viral inhibitors [56]. This process involves receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), which is activated by autophosphorylation [57]. This enables RIPK1 to activate the kinase RIPK3 within a cytoplasmic high molecular weight complex termed the necrosome. RIPK3 then phosphorylates and thereby activates the pseudo-kinase MLKL, the terminal effector of necroptosis that causes lysis of the plasma membrane [58, 59]. This facilitates release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and in the case of infected cells also pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [60], driving an inflammatory response (Fig. 1).

In ALS, necroptosis was reported to be dispensable for motor neuron degeneration, based on the observation that the absence of MLKL did not affect disease onset, progression and survival in SOD1G93A mutant mice [61]. In contrast, there was evidence of necroptosis in post-mortem examination of brains from human AD patients, with abundant expression of MLKL compared to brains from healthy controls. Moreover, necroptosis was postulated to exacerbate cognitive deficits in the APP/PS1 mouse model of AD, since treatment with the RIPK1 inhibitor necrostatin-1 reduced neuronal death, attenuated the formation of insoluble Aβ plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau in the cortex and hippocampus and ameliorated cognitive impairment [62, 63]. It is, however, noteworthy that in addition to inducing necroptosis, RIPK1 (and RIPK3) are also involved in activating caspase-8 mediated apoptosis and the production of cytokines and chemokines [64]. It remains unclear inhibition of which of these processes by necrostatin-1 reduced pathology in the APP/PS1 mice. A sub-type of disease-associated microglia has been implicated in promoting the formation of Aβ plaques in AD. A study showed that RIPK1 may promote this behaviour of microglia, thereby triggering inflammation and contributing to pathogenesis [65]. Pharmacological inhibition or genetic ablation of RIPK1 in a mouse model of AD reduced amyloid burden, the levels of inflammatory cytokines and memory deficits [65]. Therefore, RIPK1 is considered a promising target for therapeutic intervention in this disease. In preclinical models of PD, genetic ablation of MLKL or RIPK3 or pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1 exerted neuroprotective effects, with decreased dopaminergic neuron degeneration and improved motor performance. Moreover, phosphorylated (i.e. activated) MLKL was found in post-mortem brain biopsies of human PD patients [66]. In a tissue culture model of PD, treatment with a RIPK1 inhibitor protected iPSC-derived neural cells from PD patients harbouring mutations in the optic atrophy type 1 (OPA1) gene from death and reduced oxidative stress [67].

Evidence of a role of necroptosis in the pathogenesis of HD is limited. One study reported that in the R6/2 transgenic mouse model of HD, in which exon 1 of a mutated human HTT gene is expressed and driven by the human huntingtin promoter [68], treatment with Necrostatin-1 ameliorated symptoms and delayed disease progression, thus identifying a role for RIPK1 in disease progression [69]. However, to date there are no reports on the expression of necroptosis signalling proteins in post-mortem samples from HD patients. Overall, these studies provide evidence that necroptosis may play a role in disease pathogenesis and that inducers of necroptosis, such as RIPK1, may constitute promising ‘druggable’ targets for this neurodegenerative disease.

Stroke constitutes the second leading cause of mortality after ischaemic heart disease. It is caused by insufficient blood flow to the brain, triggering a cascade of pathological responses, including inflammation, ROS production and protein misfolding [70]. In animal models of stroke, such as hypoxia-ischaemia, oxygen-glucose deprivation and collagenase-induced intracerebral haemorrhage, treatment with the RIPK1 inhibitor necrostatin-1 or genetic ablation of proteins critical for necroptosis improved neurological function and attenuated neuronal cell death post brain injury [71,72,73]. While some studies have indicated that necroptosis plays a role in the pathogenesis of stroke and treatments targeting necroptosis signalling proteins have proved to be neuroprotective in various animal models [70], research into the clinical utility of necroptosis inhibitors in patients is lacking and this area warrants further investigation.

In cancer, there are contradictory reports claiming that necroptosis can either promote or inhibit tumour growth [74], perhaps depending on the type of cancer or whether necroptosis occurs in the malignant cells or in cells of the tumour microenvironment. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, RIPK1 expression is downregulated compared to healthy tissues [75], whereas in lung cancer patients and mouse models of lung cancer, RIPK1 expression is markedly elevated in the tumour tissue [76]. In a study of GBM patients, ~30% of tumours exhibited high levels of RIPK1 expression [77] and this correlated with adverse prognosis. Amongst patients with lower grade gliomas, those with higher RIPK3 expression levels had poorer prognosis [78]. In another study, upregulation of MLKL in GBM patients was associated with an unfavourable prognosis [79]. It therefore appears that increased expression of RIPK1, RIPK3 and MLKL may promote tumour growth. This may be linked to reports that necroptosis in cells of the tumour microenvironment drives angiogenesis and inflammation, which can promote cancer cell proliferation and metastasis [80]. With the observations that glioblastoma cells are highly resistant to apoptosis, activation of necroptosis or alternate mechanisms of PCD, may represent promising avenues to explore for cancer therapy. Activators of RIPK1, RIPK3 and MLKL may constitute possible approaches, although the safety of such strategies will need to be established.

Cell death associated with autophagy

Autophagy is a highly conserved process for the degradation of macro-molecular structures and even entire organelles that plays critical roles in cellular and tissue homoeostasis [81]. This process is important for regulating the cytoplasmic turnover of proteins and entire organelles. A myriad of stimuli can enhance autophagy, including nutrient deprivation, oxidative stress and protein aggregates. In these settings, autophagy reduces cell stress and provides cells with metabolites for repair, survival and growth. Autophagy can be differentiated into three subtypes: macro-autophagy, micro-autophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy; for a comprehensive review see ref. [82]. Each of these processes is distinct, however, they all converge upon lysosomes for cargo degradation and recycling of intracellular content. Although autophagy is often used to promote cell survival, in certain settings, such as the involution of salivary glands during Drosophila development [83], autophagy is associated with cell killing.

A hallmark of neurodegenerative diseases includes the accumulation of proteinaceous aggregates and ubiquitinated inclusion bodies and they are thought to be involved in the aetiology of these diseases. Aberrant autophagy is a feature of several neurological diseases. In ALS, mutations in autophagy-related genes, including SQSTM1, OPTN, TBK1, VCP and C9ORF72, are associated with familial forms of the disease. The accumulation of autophagosomes in the cytoplasm of spinal cord neurons of ALS patients has been reported [84], as well as an increase in the formation of autophagosomes in SOD1 mutant transgenic mice [85]. In the SOD1G93A mouse model of ALS loss of Atg7 accelerated neuromuscular denervation and the onset of hindlimb tremor at the early-symptomatic stage of the disease. However, at late stages of disease, autophagy had an adverse role, where loss of Atg7 slowed disease progression and increased the lifespan of the mice [86].

The accumulation of autophagosomes in neurons is a conspicuous feature of AD in both animal models and patients with observations of increased Aβ generation and accumulation in lysosomes in cells with defects in autophagy. This suggests that the turnover of Aβ is regulated in part by autophagy [87]. Microarray profiling of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons from post-mortem brain tissues from AD patients or controls revealed high expression of autophagy-related genes in early stages of AD. This correlated with increased levels of autophagosome components, increased LC3-positive puncta and defective clearance of autophagic substrates by lysosomes in CA1 pyramidal neurons [88]. Therefore, enhancement of autophagy may be a promising area of investigation for achieving neuroprotective outcomes in AD.

Defects in autophagy are associated with several molecular mechanisms underpinning PD, and several ATG genes were shown to be aberrant in PD [89]. Accordingly, dysregulated autophagy has been identified in brain tissues from PD patients and in PD animal models, suggesting that autophagy plays a role in disease pathogenesis [90].

It is a similar scenario in HD, where accumulation of the huntingtin protein (HTT) is associated with attenuated autophagy [91]. Notably, enhanced autophagy by inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin signalling was found to enhance the clearance of HTT aggregates and reduced toxicity in Drosophila and mouse models of HD [92]. Paradoxically, ablation of p62, an autophagy receptor, significantly attenuated the formation of nuclear inclusions and motor deficits and prolonged lifespan in a mouse model of HD [93]. These reports exemplify the complexity of targeting autophagy signalling in HD (and possibly other neurological diseases). Thus, substantial additional work is required to arrive at a better understanding of the role of autophagy in HD pathogenesis, so that this knowledge may be used to develop new treatments for HD that are based on manipulating this process.

The role of autophagy in GBM is controversial, with some reports claiming that it suppresses tumour growth whereas others stated that it promotes tumour growth. In U343 glioma cells, autophagy was shown to trigger cell senescence [94] and this also enhanced TMZ-induced senescence in glioma cells [95]. Triggering autophagy was reported to inhibit GBM cell migration and invasiveness, reversing the epithelial-mesenchymal transition [96]. Conversely, autophagy was also reported to exert positive effects on tumours, increasing their proliferative potential and elevated expression of p62 was correlated with poorer survival in GBM patients [97]. Perturbations in EGFR, PTEN and AKT, which are frequently mutated in GBM, have been reported to impact the regulation of autophagy [98]. Autophagy was also shown to promote survival of GBM cells [99] and to facilitate metastasis [100]. Given the ongoing controversy about the role of autophagy in glioblastoma (and many other cancers for that matter [101]), further interrogation of this pathway is warranted if it should be harnessed for therapeutic intervention in this disease.

Ferroptosis

First coined in 2012 [102], ferroptosis refers to a form of iron-dependent necrotic PCD. The final executor in ferroptosis is overwhelming lipid peroxidation causing complete cell failure. Although ferroptosis exhibits many features of what was previously commonly called oxidative stress-induced cell death, there are many aspects that distinguish it as a distinct form of cell death. For instance, ferroptosis is morphologically and functionally distinct from ‘generic’ oxidative stress, such as hydrogen peroxide-induced necrosis [102]. Many molecular components of ferroptosis have been identified, including ACSL4 and LPCAT3 that generate the membrane lipids susceptible to peroxidation [103, 104], and the glutamate-cystine antiporter system xCT required to supply cysteine to the cell. Critical to prevent lipid peroxidation are endogenous mechanisms including glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4; [105] and ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (formerly AIFM2) [106, 107] which use glutathione and ubiquinone, respectively, as reducing substrates, and tetrahydrobiopterin synthesised by GTP cyclohydrolase-1 [108]. Ferroptosis inducers include inhibitors of GPX4 (RSL3, ML210, ML162, FIN56, FINO2), disruption of glutathione synthesis (buthionine sulfoximine), disruption of cysteine supply via inhibition of system xCT (erastin, sorafenib, sulfasalazine, glutamate), iron and iron-disrupting stimuli. Endogenous inhibitors of ferroptosis include glutathione, ubiquinone, vitamin E and selenium. Exogenously applied ferroptosis inhibitors include radical trapping antioxidants (RTAs; ferrostatin-1, liproxstatin-1), inhibition of lipoxygenases (in absence of RTA activity, see below) and iron chelators (deferoxamine, deferiprone). The selectivity and potency of RTAs illustrates the unequivocal role of lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis.

Many small molecule inhibitors are redox active and exhibit significant potential to directly inhibit lipid peroxidation [109]. This is problematic when attempting to delineate additional molecular aspects of ferroptosis as such inhibitors may directly inhibit lipid peroxidation independent of interactions with their intended targets. For instance, many lipoxygenase inhibitors are redox active; this includes zileuton, NGDA, baicalein and PD146176 [109]. Therefore, the use of redox active molecules should be coupled with complementary experimental approaches in order to permit clear interpretation of the findings. Furthermore, when a redox active small molecule exhibits efficacy in a given model of disease, this may be due to inhibition of ferroptosis rather than (or in addition) to their intended action. In light of the increasing evidence for a role of ferroptosis across many conditions, this calls for a re-evaluation of previous studies involving inhibitors that are redox active and inhibit lipid peroxidation.

Specific evidence for a role of ferroptosis in a disease setting is difficult to establish. Almost all neurodegenerative diseases appear to exhibit lipid peroxidation. Likewise, dysregulated iron homoeostasis and diminished glutathione are also common features of neurodegeneration. Perhaps the best evidence comes from the protection afforded by ferroptosis inhibitors in animal models of disease and ultimately in human clinical trials. The canonical RTA ferroptosis inhibitors liproxstatin-1 and ferrostatin-1 have been reported to exhibit efficacy in mouse models of stroke [110], PD [111] and HD slice culture assays [112]. Vitamin E prevents the rapid death of neurons in conditional neuronal Gpx4 knockout mice [113, 114], whereas overexpression of GPX4 protects against intracerebral haemorrhage in rats [115].

Several ferroptosis inhibitors have been assessed in the clinic. In a phase II clinic trial for AD, the iron chelator deferoxamine significantly reduced the rate of cognitive decline in patients [116]. Surprisingly, this study is yet to be replicated after 30 years, although nasal formulations of deferoxamine are showing promise in animal models of AD [117, 118].

More recently, therapeutic strategies targeting iron have focused on the iron chelator deferiprone. Similar to deferoxamine, deferiprone inhibits ferroptosis in vitro, and exhibits efficacy in mouse models of AD, PD and ALS [119,120,121]. In two phase II trials for PD, deferiprone significantly impacted brain iron levels and either significantly delayed or trended towards slowing progression of symptoms as measured by the UPDRS [117, 121]. A third phase II trial with 140 participants has been completed but is yet to report, while a fourth phase II trial with 372 participants is currently underway. Deferiprone is also currently under clinical investigation for AD and ALS in two large phase II trials.

CuII(atsm) strongly inhibits ferroptosis induced by RSL3 or erastin in neural cells in vitro and in a cell-free lipid peroxidation system [122]. CuII(atsm) has been extensively investigated (and independently validated) in preclinical animal models and exhibits efficacy in multiple models of ALS, PD and stroke (for review see [123]). Phase I clinical trials for ALS and PD have been completed with encouraging results [124]. A phase II trial with 80 participants is currently ongoing, as well as extension trials for ALS patients from both trials.

Ferroptosis-related gene expression is associated with diagnostic and prognostic factors in glioma [125]. Many anti-cancer drugs appear to target and enhance ferroptosis to kill glioma cells, including withaferin A [126], dihydroartemisinin [127] and ibuprofen [128]. Inducing ferroptosis is thought to enhance effects of ‘traditional’ anti-cancer treatments that trigger other cell death pathways, mostly apoptosis. Feeding glioblastoma bearing mice or rats with iron enhanced the impact of radiation therapy [129, 130]. Moreover, inhibition of xCT by erastin or sulfasalazine potentiated the efficacy of temozolomide [131, 132]. Coatomer Protein Complex, Subunit Zeta 1 (COPZ1) is associated with increased tumour grade. Inhibition of COPZ1 using RNA interference inhibited tumour growth and enhanced survival in mice by increasing intracellular iron by enhancing ferritinophagy [133]. Conversely, glioblastoma cell necrosis that was reported to be driven by neutrophil-triggered ferroptosis was shown to be associated with worsened outcomes [134]. Overall, it appears that the effects of ferroptosis are dependent on many factors. Ferroptosis may kill cancer cells, however, it is not immune-silent raising the issue of what impact this may have on surrounding healthy tissues.

Pyroptosis

Pyroptosis is an inflammatory form of PCD involving activation of caspase-1 by inflammasomes. Caspase-1 proteolytically processes pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into the mature inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, respectively. Gasdermin D (GSDMD) is the critical executioner of pyroptosis [135]. Caspase-1 cleaves GSDMD and its N-terminal fragment assembles into a plasma membrane pore [136]. This is required for release of bio-active IL-1β and IL-18 as well as other cellular contents, and for the killing of the cell. Historically, pyroptosis was often thought to be a monocyte-specific form of apoptosis, as it exhibits a plasma membrane-blebbing morphology. However, the recent discovery of GSDMD and its pore-formation activity has redefined pyroptosis as a necrotic form of cell death.

Evidence for pyroptosis (accompanied by inflammasome activation and elevated IL-1β and IL-18) has been reported for many neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, PD, ALS, HD, multiple sclerosis, stroke and traumatic brain injury [137]. Inflammasome activation and pyroptosis have been found in microglia and oligodendrocytes in an animal model of multiple sclerosis, in which pathology was diminished by caspase-1 inhibition [138].

Necrosis: unregulated cell death

Necrosis is classically considered an unprogrammed and unregulated cell death process that is characterised by cell swelling, loss of membrane integrity, ‘spillage’ of intracellular contents (DAMPs and PAMPs) into the extracellular environment and dissipation of ion gradients, overall triggering an inflammatory response. Necrosis can occur due to overwhelming stimuli from outside the cell, such as hypoxia, freezing or burning, certain pathogens, physico-chemical stresses (e.g. H2O2), ischaemia-reperfusion and calcium overload [139]. Early events in necrosis include an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration and generation of reactive oxygen species culminating in events that result in irreversible cell injury. However, unlike necroptosis, necrosis lacks a defined core cellular signalling machinery but Ninj1 has recently been identified as being critical for the rupture of the plasma membrane [140]. Of note, Ninj1 is also critical for the final rupture of the plasma membrane that occurs during necroptosis, pyroptosis and the secondary necrosis that is seen when cells undergoing apoptosis are not engulfed by neighbouring phagocytes. Necrosis is observed in many pathological conditions, including myocardial infarction, stroke, several neurodegenerative diseases and in certain cancers, where factors released from necrotic malignant cells are likely to impact the tumour microenvironment [14, 141].

Since necrosis is an unprogrammed form of cell death, it has been proposed that the necrotic pathology associated with neurological diseases emanates from an interplay of finely tuned programmed necrosis cascades, such as necroptosis, ferroptosis and pyroptosis, and that this is a driver of the neurological diseases (Table 1). It is therefore anticipated that targeting the necrotic PCD pathways may provide novel opportunities for therapeutic intervention which is discussed below. Of note, it remains a distinct possibility that in neurodegenerative diseases at least some aspects of tissue damage, such as the immediate insult from the occlusion of blood vessels in stroke, is actually caused by unregulated (non-programmed) necrosis rather than by any of the programmed necrotic cell death pathways. Such tissue damage may only be alleviated by preventing or reducing the insult causing the patholoogy in the first place (e.g. increasing perfusion during stroke). Nonetheless, most of the secondary (and possibly tertiary) tissue destruction in neurodegenerative diseases may well be caused by an interplay of apoptosis and the necrotic PCD pathways. Therefore, inhibitors of MLKL, GSDMD and BAX/BAK, the effectors of necroptosis, pyroptosis or apoptosis, respectively, may allow improved outcomes for patients with these diseases [142]. It appears likely that such agents will need to be used in combination due to the ability of cells to engage another PCD process when the one they would normally undergo is blocked [143, 144].

Therapeutic implications

The development and study of mouse models (e.g. genetic modifications or treatment with toxic insults) mimicking neurological diseases has led to an understanding of key regulators of the different cell death signalling pathways and their relevance in disease pathogenesis. Even though aberrant apoptotic cell death and expression of key pro-apoptotic proteins are associated with neurodegenerative diseases, targeting apoptosis in vivo has so far proved disappointing. The clinical potential of Minocycline, a second-generation tetracycline was tested in various preclinical mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases, such as ones for ALS, PD and HD. Minocycline blocks the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, inhibiting this step in apoptosis, and was reported to upregulate the expression of anti-apoptotic BCL-2, also exhibiting anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, displaying effective neuroprotective outcomes in preclinical mouse models [145]. However, a recent randomised clinical trial reported that Minocycline was ineffective and failed to delay disease progression in patients with mild AD over a 24 month period [146]. The reason for this is likely that MOMP and loss of ATP production in mitochondria will still occur despite treatment with this agent. Thus, cells exposed to Minocycline would still be ‘functionally dead’.

Pharmacological inhibition or genetic ablation of RIPK1 has produced neuroprotective outcomes in preclinical models of AD, PD and HD. The use of the blood brain barrier-penetrant RIPK1 inhibitor DNL747 was tested in a clinical trial for AD and ALS, even though necroptosis was reported to be dispensable for the latter. DNL747 progressed through phase I trials. However, the trial was then halted in favour of its successor compound, DNL788, which is anticipated to be superior in achieving neuroprotective outcomes [147]. The efficacy of the combination of sodium phenylbuturate and Taurursodiol was recently reported in a randomised, double-blind trial for ALS. Taurursodiol was reported to exert anti-apoptotic properties, inhibiting the translocation of the apoptosis effector BAX to mitochondrial membranes, while sodium phenylbutrate, a histone deacetylase inhibitor can ameliorate toxicity from endoplasmic reticulum stress, thereby promoting cell survival. Measurement of drug impact included examination of functional decline, which was reported to be slower compared to the placebo treated control subjects, when assessed over a 24-week period [148].

Bcl2l12, a protein containing a BH2 domain (but none of the other BCL-2 family homology (BH) regions) was reported to drive the development of GBM by interacting with certain members of the BCL-2 protein family and inhibiting the activation of caspases-3 and -7, thereby inhibiting mitochondrial-induced apoptosis [149]. An early phase clinical trial (NCT03020017) in GBM involved evaluating the efficacy of utilising spherical nucleic acid gold nanoparticles composed of siRNAs targeting Bcl2l12 (NU-0129). The nanoparticles can cross the blood brain barrier; therefore, it is anticipated that NU-0129 will penetrate into the tumour tissue and will be able to inhibit the growth of GBM.

Regulators and effectors of the different cell death pathways remain attractive therapeutic targets that may form the basis for translational work that will hopefully lead to improvements for patients with these diseases. Given that the aetiology of neurological diseases is complex, where multiple cell death mechanisms often in conjunction with other cellular processes drive pathology, it appears likely that effective therapies will comprise inhibitors of more than one cell death programme plus inhibitors of additional cellular processes. Table 2 displays some key targets within cell death pathways which have advanced to clinical trials.

Conclusions and perspectives

Many diseases of the brain are associated with defects in one or several processes of PCD: either aberrant killing of cells that should survive in neurodegenerative disorders or aberrant survival of cells that should die during the development and therapy of brain cancers. In most neurodegenerative diseases it has not yet been unequivocally defined whether these defects in cell death are a true cause or at least critical contributor to disease or simply a consequence of some insult to the tissue where even effective blockade of this cell death would not offer improved therapy. In the case of brain cancer, as with all types of cancer, effective delivery of potent inducers of any type of cell death would be expected to cause tumour shrinkage, of course with the proviso that it will be safe, i.e. tolerable to vital tissues. We contend that much additional research, both basic work in animal models and studies with patient material, is needed to garner a more detailed understanding of the roles of the different processes of cell death in diseases of the brain, so that this knowledge can be harnessed to develop truly transformative advances in their treatment.

Facts

-

Neurodegenerative diseases are associated with aberrant neuronal cell death, but the processes leading to such cell death and the mode of cell death still remain unclear.

-

Glioblastoma cells are highly resistant to apoptosis; therefore, activation of alternate mechanisms of PCD may represent promising avenues to explore for therapy of this cancer.

-

With the brain’s complex cellular and architectual diversity, it is not unreasonable to predict that many forms of cell death may be occurring simultaneously in disease states. Indeed, evidence indicates this is likely the case, with various inhibitors targeting many forms of cell death having beneficial impact in the same disease model.

-

Given there are perturbations in more than one PCD signalling pathway and also unprogrammed necrosis in disease pathogenesis, effective therapies will need to comprise inhibitors of more than one type of cell death.

Open questions

-

Is a defect in a PCD signalling pathway a direct cause or a critical contributor to disease or simply a consequence of some insult to the tissue where even effective blockade of cell death would not offer improved outcome?

-

Programmed pathways of lytic cell death are inherently more immunogenic than apoptosis. Will inhibition of lytic PCD pathways be more effective in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases than blocking apoptosis because the former induces a pro-inflammatory state? Are neurons more susceptible to death in an inflammatory state?

-

The ferroptosis PCD pathway is not immune-silent. What impact would this have on surrounding healthy tissues when trying to exploit inducers of ferroptosis for the treatment of brain cancers?

References

Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972;26:239–57.

Kelly GL, Strasser A. Toward targeting antiapoptotic MCL-1 for cancer therapy. Annu Rev Cancer Biol. 2020;4:299–313.

Huang DC, Strasser A. BH3-Only proteins-essential initiators of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 2000;103:839–42.

Green DR. The coming decade of cell death research: five riddles. Cell. 2019;177:1094–107.

Singh R, Letai A, Sarosiek K. Regulation of apoptosis in health and disease: the balancing act of BCL-2 family proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:175–93.

Shi Y. Mechanisms of caspase activation and inhibition during apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2002;9:459–70.

Haanen C, Vermes I. Apoptosis: programmed cell death in fetal development. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:129–33.

Kuan CY, Roth KA, Flavell RA, Rakic P. Mechanisms of programmed cell death in the developing brain. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:291–7.

Fogarty LC, Flemmer RT, Geizer BA, Licursi M, Karunanithy A, Opferman JT, et al. Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL are essential for survival of the developing nervous system. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:1501–15.

Arbour N, Vanderluit JL, Le Grand JN, Jahani-Asl A, Ruzhynsky VA, Cheung EC, et al. Mcl-1 is a key regulator of apoptosis during CNS development and after DNA damage. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6068–78.

Motoyama N, Wang F, Roth KA, Sawa H, Nakayama K, Nakayama K, et al. Massive cell death of immature hematopoietic cells and neurons in Bcl-x-deficient mice. Science. 1995;267:1506–10.

Ke FFS, Vanyai HK, Cowan AD, Delbridge ARD, Whitehead L, Grabow S, et al. Embryogenesis and adult life in the absence of intrinsic apoptosis effectors BAX, BAK, and BOK. Cell. 2018;173:1217–30 e17.

Grabow S, Kueh AJ, Ke F, Vanyai HK, Sheikh BN, Dengler MA, et al. Subtle changes in the levels of BCL-2 proteins cause severe craniofacial abnormalities. Cell Rep. 2018;24:3285–95 e4.

Gorman AM. Neuronal cell death in neurodegenerative diseases: recurring themes around protein handling. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:2263–80.

Carlsson SK, Brothers SP, Wahlestedt C. Emerging treatment strategies for glioblastoma multiforme. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:1359–70.

Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, Gage FH. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;140:918–34.

Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–95.

Dong XX, Wang Y, Qin ZH. Molecular mechanisms of excitotoxicity and their relevance to pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Pharm Sin. 2009;30:379–87.

Soto C, Pritzkow S. Protein misfolding, aggregation, and conformational strains in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1332–40.

Green DR. Apoptotic pathways: paper wraps stone blunts scissors. Cell. 2000;102:1–4.

Wang X. The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2922–33.

Puthalakath H, Strasser A. Keeping killers on a tight leash: transcriptional and post-translational control of the pro-apoptotic activity of BH3-only proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:505–12.

Chen L, Willis SN, Wei A, Smith BJ, Fletcher JI, Hinds MG, et al. Differential targeting of prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins by their BH3-only ligands allows complementary apoptotic function. Mol Cell. 2005;17:393–403.

Strasser A, Jost PJ, Nagata S. The many roles of FAS receptor signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2009;30:180–92.

Fulda S, Debatin KM. Extrinsic versus intrinsic apoptosis pathways in anticancer chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2006;25:4798–811.

Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, Turner MR, Eisen A, Hardiman O, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2011;377:942–55.

Moujalled D, White AR. Advances in the development of disease-modifying treatments for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:227–43.

Ferraiuolo L, Kirby J, Grierson AJ, Sendtner M, Shaw PJ. Molecular pathways of motor neuron injury in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:616–30.

Pasinelli P, Belford ME, Lennon N, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT, Trotti D, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated SOD1 mutant proteins bind and aggregate with Bcl-2 in spinal cord mitochondria. Neuron. 2004;43:19–30.

Boillee S, Vande Velde C, Cleveland DW. ALS: a disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors. Neuron. 2006;52:39–59.

Gonzalez de Aguilar JL, Gordon JW, Rene F, de Tapia M, Lutz-Bucher B, Gaiddon C, et al. Alteration of the Bcl-x/Bax ratio in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: evidence for the implication of the p53 signaling pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:406–15.

Mu X, He J, Anderson DW, Trojanowski JQ, Springer JE. Altered expression of bcl-2 and bax mRNA in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord motor neurons. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:379–86.

Ekegren T, Grundstrom E, Lindholm D, Aquilonius SM. Upregulation of Bax protein and increased DNA degradation in ALS spinal cord motor neurons. Acta Neurol Scand. 1999;100:317–21.

Hetz C, Thielen P, Fisher J, Pasinelli P, Brown RH, Korsmeyer S, et al. The proapoptotic BCL-2 family member BIM mediates motoneuron loss in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1386–9.

Li M, Ona VO, Guegan C, Chen M, Jackson-Lewis V, Andrews LJ, et al. Functional role of caspase-1 and caspase-3 in an ALS transgenic mouse model. Science. 2000;288:335–9.

Vukosavic S, Stefanis L, Jackson-Lewis V, Guegan C, Romero N, Chen C, et al. Delaying caspase activation by Bcl-2: A clue to disease retardation in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9119–25.

Reyes NA, Fisher JK, Austgen K, VandenBerg S, Huang EJ, Oakes SA. Blocking the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway preserves motor neuron viability and function in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3673–9.

Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006189.

Ohyagi Y, Asahara H, Chui DH, Tsuruta Y, Sakae N, Miyoshi K, et al. Intracellular Abeta42 activates p53 promoter: a pathway to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2005;19:255–7.

Zhang Y, McLaughlin R, Goodyer C, LeBlanc A. Selective cytotoxicity of intracellular amyloid beta peptide1-42 through p53 and Bax in cultured primary human neurons. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:519–29.

Kitamura Y, Shimohama S, Kamoshima W, Ota T, Matsuoka Y, Nomura Y, et al. Alteration of proteins regulating apoptosis, Bcl-2, Bcl-x, Bax, Bak, Bad, ICH-1 and CPP32, in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1998;780:260–9.

Park G, Nhan HS, Tyan SH, Kawakatsu Y, Zhang C, Navarro M, et al. Caspase activation and caspase-mediated cleavage of APP is associated with amyloid beta-protein-induced synapse loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107839.

Pellegrini L, Passer BJ, Tabaton M, Ganjei JK, D’Adamio L. Alternative, non-secretase processing of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid precursor protein during apoptosis by caspase-6 and -8. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21011–6.

Lu DC, Soriano S, Bredesen DE, Koo EH. Caspase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein modulates amyloid beta-protein toxicity. J Neurochem. 2003;87:733–41.

Zhang Y, Ona VO, Li M, Drozda M, Dubois-Dauphin M, Przedborski S, et al. Sequential activation of individual caspases, and of alterations in Bcl-2 proapoptotic signals in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1184–92.

Leon R, Bhagavatula N, Ulukpo O, McCollum M, Wei J. BimEL as a possible molecular link between proteasome dysfunction and cell death induced by mutant huntingtin. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:1915–25.

Roberts SL, Evans T, Yang Y, Fu Y, Button RW, Sipthorpe RJ, et al. Bim contributes to the progression of Huntington’s disease-associated phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 2020;29:216–27.

Vis JC, Schipper E, de Boer-van Huizen RT, Verbeek MM, de Waal RM, Wesseling P, et al. Expression pattern of apoptosis-related markers in Huntington’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109:321–8.

Klein C, Westenberger A. Genetics of Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a008888.

Bernardini JP, Brouwer JM, Tan IK, Sandow JJ, Huang S, Stafford CA, et al. Parkin inhibits BAK and BAX apoptotic function by distinct mechanisms during mitophagy. EMBO J. 2019;38:e99916.

Iaccarino C, Crosio C, Vitale C, Sanna G, Carri MT, Barone P. Apoptotic mechanisms in mutant LRRK2-mediated cell death. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1319–26.

Tatton NA. Increased caspase 3 and Bax immunoreactivity accompany nuclear GAPDH translocation and neuronal apoptosis in Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2000;166:29–43.

Blandini F, Mangiagalli A, Cosentino M, Marino F, Samuele A, Rasini E, et al. Peripheral markers of apoptosis in Parkinson’s disease: the effect of dopaminergic drugs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1010:675–8.

Jiang Z, Zheng X, Rich KM. Down-regulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression with bispecific antisense treatment in glioblastoma cell lines induce cell death. J Neurochem. 2003;84:273–81.

Liwak U, Jordan LE, Von-Holt SD, Singh P, Hanson JE, Lorimer IA, et al. Loss of PDCD4 contributes to enhanced chemoresistance in Glioblastoma multiforme through de-repression of Bcl-xL translation. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1365–72.

Tummers B, Green DR. Caspase-8: regulating life and death. Immunol Rev. 2017;277:76–89.

Laurien L, Nagata M, Schunke H, Delanghe T, Wiederstein JL, Kumari S, et al. Autophosphorylation at serine 166 regulates RIP kinase 1-mediated cell death and inflammation. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1747.

Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao D, et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell. 2012;148:213–27.

Murphy JM, Czabotar PE, Hildebrand JM, Lucet IS, Zhang JG, Alvarez-Diaz S, et al. The pseudokinase MLKL mediates necroptosis via a molecular switch mechanism. Immunity. 2013;39:443–53.

Samson AL, Zhang Y, Geoghegan ND, Gavin XJ, Davies KA, Mlodzianoski MJ, et al. MLKL trafficking and accumulation at the plasma membrane control the kinetics and threshold for necroptosis. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3151.

Wang T, Perera ND, Chiam MDF, Cuic B, Wanniarachchillage N, Tomas D, et al. Necroptosis is dispensable for motor neuron degeneration in a mouse model of ALS. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:1728–39.

Yang SH, Lee DK, Shin J, Lee S, Baek S, Kim J, et al. Nec-1 alleviates cognitive impairment with reduction of Abeta and tau abnormalities in APP/PS1 mice. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:61–77.

Caccamo A, Branca C, Piras IS, Ferreira E, Huentelman MJ, Liang WS, et al. Necroptosis activation in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1236–46.

Alvarez-Diaz S, Dillon CP, Lalaoui N, Tanzer MC, Rodriguez DA, Lin A, et al. The pseudokinase MLKL and the kinase RIPK3 have distinct roles in autoimmune disease caused by loss of death-receptor-induced apoptosis. Immunity. 2016;45:513–26.

Ofengeim D, Mazzitelli S, Ito Y, DeWitt JP, Mifflin L, Zou C, et al. RIPK1 mediates a disease-associated microglial response in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E8788–97.

Onate M, Catenaccio A, Salvadores N, Saquel C, Martinez A, Moreno-Gonzalez I, et al. The necroptosis machinery mediates axonal degeneration in a model of Parkinson disease. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:1169–85.

Iannielli A, Bido S, Folladori L, Segnali A, Cancellieri C, Maresca A, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of necroptosis protects from dopaminergic neuronal cell death in Parkinson’s disease models. Cell Rep. 2018;22:2066–79.

Mangiarini L, Sathasivam K, Seller M, Cozens B, Harper A, Hetherington C, et al. Exon 1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell. 1996;87:493–506.

Zhu S, Zhang Y, Bai G, Li H. Necrostatin-1 ameliorates symptoms in R6/2 transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e115.

Sekerdag E, Solaroglu I, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y. Cell death mechanisms in stroke and novel molecular and cellular treatment options. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16:1396–415.

Su X, Wang H, Kang D, Zhu J, Sun Q, Li T, et al. Necrostatin-1 ameliorates intracerebral hemorrhage-induced brain injury in mice through inhibiting RIP1/RIP3 pathway. Neurochem Res. 2015;40:643–50.

Northington FJ, Chavez-Valdez R, Graham EM, Razdan S, Gauda EB, Martin LJ. Necrostatin decreases oxidative damage, inflammation, and injury after neonatal HI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:178–89.

Vieira M, Fernandes J, Carreto L, Anuncibay-Soto B, Santos M, Han J, et al. Ischemic insults induce necroptotic cell death in hippocampal neurons through the up-regulation of endogenous RIP3. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;68:26–36.

Qin X, Ma D, Tan YX, Wang HY, Cai Z. The role of necroptosis in cancer: a double-edged sword? Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2019;1871:259–66.

McCormick KD, Ghosh A, Trivedi S, Wang L, Coyne CB, Ferris RL, et al. Innate immune signaling through differential RIPK1 expression promote tumor progression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37:522–9.

Wang Q, Chen W, Xu X, Li B, He W, Padilla MT, et al. RIP1 potentiates BPDE-induced transformation in human bronchial epithelial cells through catalase-mediated suppression of excessive reactive oxygen species. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2119–28.

Park S, Hatanpaa KJ, Xie Y, Mickey BE, Madden CJ, Raisanen JM, et al. The receptor interacting protein 1 inhibits p53 induction through NF-kappaB activation and confers a worse prognosis in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2809–16.

Vergara GA, Eugenio GC, Malheiros SMF, Victor EDS, Weinlich R. RIPK3 is a novel prognostic marker for lower grade glioma and further enriches IDH mutational status subgrouping. J Neurooncol. 2020;147:587–94.

Dong Y, Sun Y, Huang Y, Dwarakanath B, Kong L, Lu JJ. Upregulated necroptosis-pathway-associated genes are unfavorable prognostic markers in low-grade glioma and glioblastoma multiforme. Transl Cancer Res. 2019;8:821–7.

Gong Y, Fan Z, Luo G, Yang C, Huang Q, Fan K, et al. The role of necroptosis in cancer biology and therapy. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:100.

Ohsumi Y. Historical landmarks of autophagy research. Cell Res. 2014;24:9–23.

Yang Y, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy and disease: unanswered questions. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:858–71.

Doherty J, Baehrecke EH. Life, death and autophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:1110–7.

Sasaki S. Autophagy in spinal cord motor neurons in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70:349–59.

Morimoto N, Nagai M, Ohta Y, Miyazaki K, Kurata T, Morimoto M, et al. Increased autophagy in transgenic mice with a G93A mutant SOD1 gene. Brain Res. 2007;1167:112–7.

Rudnick ND, Griffey CJ, Guarnieri P, Gerbino V, Wang X, Piersaint JA, et al. Distinct roles for motor neuron autophagy early and late in the SOD1(G93A) mouse model of ALS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E8294–303.

Boland B, Kumar A, Lee S, Platt FM, Wegiel J, Yu WH, et al. Autophagy induction and autophagosome clearance in neurons: relationship to autophagic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6926–37.

Bordi M, Berg MJ, Mohan PS, Peterhoff CM, Alldred MJ, Che S, et al. Autophagy flux in CA1 neurons of Alzheimer hippocampus: increased induction overburdens failing lysosomes to propel neuritic dystrophy. Autophagy. 2016;12:2467–83.

Hardy J, Lewis P, Revesz T, Lees A, Paisan-Ruiz C. The genetics of Parkinson’s syndromes: a critical review. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:254–65.

Friedman LG, Lachenmayer ML, Wang J, He L, Poulose SM, Komatsu M, et al. Disrupted autophagy leads to dopaminergic axon and dendrite degeneration and promotes presynaptic accumulation of alpha-synuclein and LRRK2 in the brain. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7585–93.

Wold MS, Lim J, Lachance V, Deng Z, Yue Z. ULK1-mediated phosphorylation of ATG14 promotes autophagy and is impaired in Huntington’s disease models. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:76.

Ravikumar B, Vacher C, Berger Z, Davies JE, Luo S, Oroz LG, et al. Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36:585–95.

Kurosawa M, Matsumoto G, Kino Y, Okuno M, Kurosawa-Yamada M, Washizu C, et al. Depletion of p62 reduces nuclear inclusions and paradoxically ameliorates disease phenotypes in Huntington’s model mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:1092–105.

Lee JS, Oh E, Yoo JY, Choi KS, Yoon MJ, Yun CO. Adenovirus expressing dual c-Met-specific shRNA exhibits potent antitumor effect through autophagic cell death accompanied by senescence-like phenotypes in glioblastoma cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:4051–65.

Hombach-Klonisch S, Mehrpour M, Shojaei S, Harlos C, Pitz M, Hamai A, et al. Glioblastoma and chemoresistance to alkylating agents: Involvement of apoptosis, autophagy, and unfolded protein response. Pharm Ther. 2018;184:13–41.

Catalano M, D’Alessandro G, Lepore F, Corazzari M, Caldarola S, Valacca C, et al. Autophagy induction impairs migration and invasion by reversing EMT in glioblastoma cells. Mol Oncol. 2015;9:1612–25.

Jennewein L, Ronellenfitsch MW, Antonietti P, Ilina EI, Jung J, Stadel D, et al. Diagnostic and clinical relevance of the autophago-lysosomal network in human gliomas. Oncotarget. 2016;7:20016–32.

Kwon Y, Kim M, Jung HS, Kim Y, Jeoung D. Targeting autophagy for overcoming resistance to anti-EGFR treatments. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:1374.

Hu YL, DeLay M, Jahangiri A, Molinaro AM, Rose SD, Carbonell WS, et al. Hypoxia-induced autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and adaptation to antiangiogenic treatment in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1773–83.

Mowers EE, Sharifi MN, Macleod KF. Autophagy in cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2017;36:1619–30.

Kimmelman AC, White E. Autophagy and tumor metabolism. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1037–43.

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–72.

Dixon SJ, Winter GE, Musavi LS, Lee ED, Snijder B, Rebsamen M, et al. Human haploid cell genetics reveals roles for lipid metabolism genes in nonapoptotic cell death. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:1604–9.

Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:91–8.

Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156:317–31.

Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, da Silva MC, Ingold I, et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2019;575:693–8.

Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong L, Ford B, Tang PH, et al. The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature. 2019;575:688–92.

Kraft VAN, Bezjian CT, Pfeiffer S, Ringelstetter L, Muller C, Zandkarimi F, et al. GTP cyclohydrolase 1/tetrahydrobiopterin counteract ferroptosis through lipid remodeling. ACS Cent Sci. 2020;6:41–53.

Shah R, Shchepinov MS, Pratt DA. Resolving the role of lipoxygenases in the initiation and execution of ferroptosis. ACS Cent Sci. 2018;4:387–96.

Tuo QZ, Lei P, Jackman KA, Li XL, Xiong H, Li XL, et al. Tau-mediated iron export prevents ferroptotic damage after ischemic stroke. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:1520–30.

Do Van B, Gouel F, Jonneaux A, Timmerman K, Gele P, Petrault M, et al. Ferroptosis, a newly characterized form of cell death in Parkinson’s disease that is regulated by PKC. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;94:169–78.

Skouta R, Dixon SJ, Wang J, Dunn DE, Orman M, Shimada K, et al. Ferrostatins inhibit oxidative lipid damage and cell death in diverse disease models. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:4551–6.

Hambright WS, Fonseca RS, Chen L, Na R, Ran Q. Ablation of ferroptosis regulator glutathione peroxidase 4 in forebrain neurons promotes cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration. Redox Biol. 2017;12:8–17.

Chen L, Hambright WS, Na R, Ran Q. Ablation of the ferroptosis inhibitor glutathione peroxidase 4 in neurons results in rapid motor neuron degeneration and paralysis. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:28097–106.

Zhang Z, Wu Y, Yuan S, Zhang P, Zhang J, Li H, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4 participates in secondary brain injury through mediating ferroptosis in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Brain Res. 2018;1701:112–25.

Crapper McLachlan DR, Dalton AJ, Kruck TP, Bell MY, Smith WL, Kalow W, et al. Intramuscular desferrioxamine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1991;337:1304–8.

Guo C, Wang T, Zheng W, Shan ZY, Teng WP, Wang ZY. Intranasal deferoxamine reverses iron-induced memory deficits and inhibits amyloidogenic APP processing in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:562–75.

Zhang Y, He ML. Deferoxamine enhances alternative activation of microglia and inhibits amyloid beta deposits in APP/PS1 mice. Brain Res. 2017;1677:86–92.

Rao SS, Portbury SD, Lago L, Bush AI, Adlard PA. The iron chelator deferiprone improves the phenotype in a mouse model of tauopathy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;78:1783.

Moreau C, Danel V, Devedjian JC, Grolez G, Timmerman K, Laloux C, et al. Could conservative iron chelation lead to neuroprotection in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;29:742–8.

Devos D, Moreau C, Devedjian JC, Kluza J, Petrault M, Laloux C, et al. Targeting chelatable iron as a therapeutic modality in Parkinson’s disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21:195–210.

Southon A, Szostak K, Acevedo KM, Dent KA, Volitakis I, Belaidi AA, et al. Cu(II) (atsm) inhibits ferroptosis: Implications for treatment of neurodegenerative disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:656–67.

Nikseresht S, Hilton JBW, Kysenius K, Liddell JR, Crouch PJ. Copper-ATSM as a treatment for ALS: support from mutant SOD1 models and beyond. Life (Basel). 2020;10:271.

Rowe D, Mathers S, Smith G, Windebank E, Rogers M-L, Noel K, et al. Modification of ALS disease progression in a phase 1 trial of CuATSM. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2018;19:280–81.

Liu HJ, Hu HM, Li GZ, Zhang Y, Wu F, Liu X, et al. Ferroptosis-related gene signature predicts glioma cell death and glioma patient progression. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:538.

Hassannia B, Wiernicki B, Ingold I, Qu F, Van Herck S, Tyurina YY, et al. Nano-targeted induction of dual ferroptotic mechanisms eradicates high-risk neuroblastoma. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:3341–55.

Yi R, Wang H, Deng C, Wang X, Yao L, Niu W, et al. Dihydroartemisinin initiates ferroptosis in glioblastoma through GPX4 inhibition. Biosci Rep. 2020;40:BSR20193314.

Gao X, Guo N, Xu H, Pan T, Lei H, Yan A, et al. Ibuprofen induces ferroptosis of glioblastoma cells via downregulation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 signaling pathway. Anticancer Drugs. 2020;31:27–34.

Ivanov SD, Semenov AL, Mikhelson VM, Kovan’ko EG, Iamshanov VA. [Effects of iron ion additional introduction in radiation therapy of tumor-bearing animals]. Radiats Biol Radioecol. 2013;53:296–303.

Ivanov SD, Semenov AL, Kovan’ko EG, Yamshanov VA. Effects of iron ions and iron chelation on the efficiency of experimental radiotherapy of animals with gliomas. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2015;158:800–3.

Sehm T, Rauh M, Wiendieck K, Buchfelder M, Eyupoglu IY, Savaskan NE. Temozolomide toxicity operates in a xCT/SLC7a11 dependent manner and is fostered by ferroptosis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:74630–47.

Sehm T, Fan Z, Ghoochani A, Rauh M, Engelhorn T, Minakaki G, et al. Sulfasalazine impacts on ferroptotic cell death and alleviates the tumor microenvironment and glioma-induced brain edema. Oncotarget. 2016;7:36021–33.

Zhang Y, Kong Y, Ma Y, Ni S, Wikerholmen T, Xi K, et al. Loss of COPZ1 induces NCOA4 mediated autophagy and ferroptosis in glioblastoma cell lines. Oncogene. 2021;40:1425–39.

Yee PP, Wei Y, Kim SY, Lu T, Chih SY, Lawson C, et al. Neutrophil-induced ferroptosis promotes tumor necrosis in glioblastoma progression. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5424.

Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526:660–5.

Ding J, Wang K, Liu W, She Y, Sun Q, Shi J, et al. Pore-forming activity and structural autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature. 2016;535:111–6.

Voet S, Srinivasan S, Lamkanfi M, van Loo G. Inflammasomes in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. EMBO Mol Med. 2019;11:e10248.

McKenzie BA, Mamik MK, Saito LB, Boghozian R, Monaco MC, Major EO, et al. Caspase-1 inhibition prevents glial inflammasome activation and pyroptosis in models of multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E6065–74.

Vanlangenakker N, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. Many stimuli pull the necrotic trigger, an overview. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:75–86.

Kayagaki N, Kornfeld OS, Lee BL, Stowe IB, O’Rourke K, Li Q, et al. NINJ1 mediates plasma membrane rupture during lytic cell death. Nature. 2021;591:131–6.

Vakkila J, Lotze MT. Inflammation and necrosis promote tumour growth. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:641–8.

Place DE, Kanneganti TD. Cell death-mediated cytokine release and its therapeutic implications. J Exp Med. 2019;216:1474–86.

Doerflinger M, Deng Y, Whitney P, Salvamoser R, Engel S, Kueh AJ, et al. Flexible usage and interconnectivity of diverse cell death pathways protect against intracellular infection. Immunity. 2020;53:533–47 e7.

Bedoui S, Herold MJ, Strasser A. Emerging connectivity of programmed cell death pathways and its physiological implications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:678–95.

Kim HS, Suh YH. Minocycline and neurodegenerative diseases. Behav Brain Res. 2009;196:168–79.

Howard R, Zubko O, Gray R, Bradley R, Harper E, Kelly L, et al. Minocycline 200 mg or 400 mg versus placebo for mild Alzheimer’s disease: the MADE phase II, three-arm RCT. Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation. Southampton (UK); 2020.

Mullard A. Microglia-targeted candidates push the Alzheimer drug envelope. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:303–5.

Paganoni S, Macklin EA, Hendrix S, Berry JD, Elliott MA, Maiser S, et al. Trial of sodium phenylbutyrate-taurursodiol for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:919–30.

Stegh AH, Kesari S, Mahoney JE, Jenq HT, Forloney KL, Protopopov A, et al. Bcl2L12-mediated inhibition of effector caspase-3 and caspase-7 via distinct mechanisms in glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10703–8.

Strasser A, O’Connor L, Dixit VM. Apoptosis signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:217–45.

Bergmann A. Autophagy and cell death: no longer at odds. Cell. 2007;131:1032–4.

Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Vandenabeele P, Abrams J, Alnemri ES, Baehrecke EH, et al. Classification of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:3–11.

Field KM, Simes J, Nowak AK, Cher L, Wheeler H, Hovey EJ, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of carboplatin and bevacizumab in recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:1504–13.

Lesueur P, Lequesne J, Grellard JM, Dugue A, Coquan E, Brachet PE, et al. Phase I/IIa study of concomitant radiotherapy with olaparib and temozolomide in unresectable or partially resectable glioblastoma: OLA-TMZ-RTE-01 trial protocol. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:198.

Mandrioli J, D’Amico R, Zucchi E, Gessani A, Fini N, Fasano A, et al. Rapamycin treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: protocol for a phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, clinical trial (RAP-ALS trial). Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11119.

Zhu CW, Grossman H, Neugroschl J, Parker S, Burden A, Luo X, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of resveratrol with glucose and malate (RGM) to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;4:609–16.

Turner RS, Thomas RG, Craft S, van Dyck CH, Mintzer J, Reynolds BA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of resveratrol for Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2015;85:1383–91.

Sotelo J, Briceno E, Lopez-Gonzalez MA. Adding chloroquine to conventional treatment for glioblastoma multiforme: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:337–43.

Martin-Bastida A, Ward RJ, Newbould R, Piccini P, Sharp D, Kabba C, et al. Brain iron chelation by deferiprone in a phase 2 randomised double-blinded placebo controlled clinical trial in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1398.

Funding

Work by the authors is supported in part by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Programme Grant #101671 awarded to AS, NHMRC Fellowship #1020363 awarded to AS, Leukaemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS) SCOR Grant #7001-13, awarded to AS; the estate of Anthony (Toni) Redstone OAM awarded to AS and operational infrastructure grants through the Australian Government NHMRCS IRIISS and the Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DM planned the review. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the review.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

DM and AS are employees of The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, which receives milestone payments and royalties from Genentech and AbbVie for the development of ABT-199/venetoclax. AS collaborates with Servier on the development of MCL-1-specific BH3 mimetic drugs for cancer therapy. JRL has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Edited by: G. Melino

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moujalled, D., Strasser, A. & Liddell, J.R. Molecular mechanisms of cell death in neurological diseases. Cell Death Differ 28, 2029–2044 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-021-00814-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-021-00814-y

This article is cited by

-

Nicotine restores olfactory function by activation of prok2R/Akt/FoxO3a axis in Parkinson’s disease

Journal of Translational Medicine (2024)

-