Abstract

Infant oral mutilation (IOM) is a traditional practice involving extraction of an infant's unerupted primary tooth buds. IOM has implications for oral and overall health due to blood loss, infection or transmission of bloodborne diseases, such as human immunodeficiency virus. IOM also leads to long-term dental complications, such as malformation of the child's permanent dentition. IOM is practised primarily in East Africa but can also be seen among immigrant populations in other countries. Currently, there are no tools for a comparative IOM diagnosis and reporting. The aim of this paper is to describe a data collection tool for healthcare practitioners, which was created based on the existing literature and a clinical consultation with senior clinical and public health physicians working in the field.

The tool can be used to record IOM-related data for appropriate diagnosis, management and treatment, as well as for monitoring preventive interventions on a community level. Furthermore, this article also summarises clinical guidelines to support practitioners with the management of acute IOM cases. The article concludes by providing recommendations and examples of community education and engagement programmes that could guide the development of interventions to eradicate IOM globally.

Key points

-

Infant oral mutilation (IOM) involves extraction of an infant's unerupted primary tooth buds and has acute and chronic implications for both oral and overall health.

-

As presented in this paper, a comprehensive data collection is pivotal in diagnosing, managing, monitoring and preventing IOM, thereby reducing the associated morbidity and mortality.

-

Through advocacy, community engagement, and education and involvement of dental and other healthcare professionals, IOM can be addressed locally and globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infant oral mutilation (IOM) is a traditional practice that is prevalent in many African countries but practised most often in East Africa.1,2 IOM involves the extraction of an infant's unerupted primary teeth or ‘tooth buds' without anaesthesia.1,2 In various communities, the tooth buds may be referred to as ‘false teeth', Lugbara teeth, Nylon teeth, Lawalawa or Ebino.1,2,3,4,5 This practice does not have any health benefits. It is typically motivated by the belief that existing tooth buds, which may resemble worms under the mucosa, may be a cause of childhood diseases, such as diarrhoea and vomiting. Thus, tooth buds are removed to prevent and/or treat those diseases. IOM may also be performed for other reasons, such as superstitions or cultural beliefs.6,7,8,9The procedure is often carried out by elders or community healers, typically using unsanitary methods and exposing the infant to pain and risk of medical complications, such as anaemia and infection (for example, tetanus or human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).10 IOM is performed on infants at approximately seven months of age. The practice is most often sought by parents from rural areas and/or a lower socio-economic background.1

IOM is performed on the mandible around three times more than the maxilla, as the mandibular canine tooth bud is more visible and palpable than the maxillary canine tooth bud.11 IOM has both dental and non-dental outcomes that affect an individual's health and quality of life. Infants usually require hospitalisation following IOM due to infection or blood loss. A 2003 study by Accorsi et al.1 explored morbidity and mortality associated with IOM complications among infants (age 0-4 years) admitted to the paediatric ward of St. Mary's Hospital, Uganda, in 1999.1 According to the study, the average time between the beginning of symptoms that lead to IOM and hospital admission was 8.4 days, while it was 4.2 days between IOM and hospitalisation.1 Under certain circumstances, IOM can also lead to death - the fatality rate can be as high as 21%, as reported in a study based in Northern Uganda.12

Although awareness of other traditional practices, such as female genital mutilation (FGM) is increasing globally, the dangerous and life-threatening implications of IOM are largely unknown by many governments and aid organisations, particularly in the UK and other countries outside of Africa. As far as the authors are aware, there are no public health interventions in place in the UK to monitor, prevent and manage IOM. Anecdotal incidents of presence of IOM cases have been reported in the UK, but they are not systematically recorded. For example, IOM was reported in UK-born Somali children in Sheffield.13 IOM is a human rights issue that must be addressed to protect the health and wellbeing of infants and children.9 To aid health professionals to diagnose, treat and prevent IOM, this article provides a data collection tool and guidelines on clinical management of IOM, as well as public health recommendations to inform IOM-related community interventions.

Geographic distribution and prevalence

While data are not routinely collected, there are some published case reports and primary research articles that provide indication for the existence of IOM practice in different countries. For instance, there are publications that describe the practice of IOM in a range of African countries (Fig. 1), including the Democratic Republic of the Congo,3Uganda,1 Tchad,14 Tanzania,4Sudan,15,16 Somalia,17 Ethiopia,11,18Angola19 and Kenya.20 Recently, due to immigration and the global movement of populations, IOM cases have also been reported in New Zealand,21 the UK,22 Israel18 and Sweden,23where dental professionals may not necessarily be equipped with the knowledge or skills to diagnose and manage the consequences of IOM.24Though dental and medical professionals outside of East Africa may not observe early cases of IOM, they are likely to see cases of IOM in older children and even adults that are suffering from the long-term consequences of IOM on permanent teeth and soft and hard tissues of the oral cavity. Therefore, building greater awareness of IOM and preventing its complications, while also advocating for it to end, are of paramount importance to global population health.

Two studies from 1992 and 1997 reported an increase in IOM practice within Tanzania, with rates increasing from 37.4% to 60.3% in Dodoma (capital of Tanzania) over this five-year period.25,26 Similarly, in Kenya, in 1988, 35% of 5-7-year-old infants had undergone IOM, whereas a study published in 1995 indicated that approximately 72% of infants aged 3-7 years had undergone IOM, doubling the prevalence in seven years.20,27 Due to a lack of recent data, it is unclear if this upward trend has continued over the past few years and whether the trend is due to a rise in the incidence of IOM or better reporting over the years. However, a recent study found the IOM prevalence to be 61% among Kenyan adolescents from Maasai Mara.28

Consequences of IOM

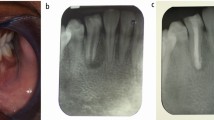

IOM not only exposes infants to pain and blood loss, but there are also many dental and other negative, non-dental outcomes associated with this practice. At the time of the procedure, or shortly after, infants may suffer from septicaemia, severe anaemia, fever, diarrhoea and dyspnea and may require hospitalisation.2,10 Furthermore, infants may be exposed to infections such as HIV, hepatitis, tetanus, osteomyelitis and osteitis due to the unsterilised instruments used, which include hot nails, bicycle spokes and pointed penknifes.1,7 The removal of tooth buds in an uncontrolled environment also has consequences for primary and permanent teeth. If the tooth bud is incompletely removed, this could lead to malformed primary teeth, dilacerated or deformed roots, or other developmental abnormalities, such as peg-shaped lateral incisors or enamel hypoplasia. In case of damage to the permanent tooth buds (developing adjacent to the primary tooth buds), failure of development or impaction, dislocation and early eruption of permanent teeth can also be observed.1,7,11,14,18,31 Other consequences of IOM may include loss of alveolar bone, scar tissue formation on the site of trauma and mesial movement of teeth located distally (behind the removed tooth bud) into the empty space.1,7,11,14,18,31 Collectively, these dental outcomes can negatively impact a child's wellbeing and overall quality of life.

IOM is also associated with long-term dental complications that are more likely to be seen by clinicians based in the UK and other countries outside East Africa. For example, in patients with missing teeth or midline shift, malocclusion may contribute to secondary trauma and increase the need for orthodontic treatment, which is usually not readily available in communities where IOM is prevalent.14,32 In rare cases, IOM is also associated with formation of odontomas, which are benign odontogenic tumours of epithelial and mesenchymal origin and require surgical removal and extensive post-operative care.15

Data collection tool for IOM

Congenital absence of canines is rare in Africa. A 2015 review reported the prevalence of congenitally missing teeth to be 6.34% for Africa compared to 16.2% for Asia and 15.7% for Europe.33 Therefore, any infant presenting with missing primary canines should be assessed for having undergone IOM.3 For IOM cases, data collection is important in making appropriate diagnoses, providing subsequent treatment and identifying long-term complications promptly.1,7

As far as the authors are aware, there is no data collection tool to support healthcare providers in recording or assessing cases of IOM. As a result, there is a lack of consistent and comprehensive data collection on IOM, which complicates the monitoring of clinical and public health interventions. Appendix 1 offers a tool to be used by healthcare professionals to collect data for diagnosis and management of IOM, as well as to monitor and measure the impact of a community-based intervention targeting IOM.1,7 The authors created this tool by integrating certain variables discussed in the existing literature with the variables that authors considered critical based on consultation with clinical and public health practitioners working in the field.1,3,10,11,12,17,22,27 This tool is to be used by anyone in healthcare, including but not limited to, medical doctors, dental professionals and nurses, to collect data on IOM as a way to compare trends temporally and spatially.

This tool includes questions regarding patients' demographic data to understand the IOM trends for different ages and ethnic groups, which may inform public health efforts. The data collection tool can be used everywhere, in print or online, for record-keeping at clinics and healthcare centres or by community and public health workers, to identify the need for a community-based intervention. This tool can be filled in at the time when a patient is seen by a healthcare professional, or as a ‘before and after' survey for evaluation of a public health intervention. Although multiple case reports have been published on IOM previously, this tool provides clinicians with a structured format on record-keeping and reporting of IOM cases, both within and beyond the UK. The authors are currently developing a database, which will be hosted on the End IOM (https://www.endiom.org/) website to record all reported IOM cases.34 Further details will be published on the website. Clinicians can send their questions to the Global Child Dental Fund's team at info@gcdfund.org.

Clinical management of IOM

Patients who are confirmed or suspected cases of IOM may benefit from a complete intra- and extra-oral examination. Key indicators to assess include: pain; swelling; blister and/or open wounds; redness and/or white patches; and any damage to teeth and/or gums.35 A complete clinical examination must be performed with the patient either seated or laying down under good lighting. Use of sterilised instruments, such as the mirror and tongue depressor, is encouraged. The healthcare professional must also use disposable gloves that have not been previously used.

For patients presenting with a suspected or confirmed IOM case, Figure 2 outlines the management of IOM-associated acute (seen in countries where IOM is performed) and chronic (seen in countries where individuals immigrate to) complications that may be performed by any medical professional.

Flowchart to guide clinical management of IOM36

Current efforts to eradicate IOM

There is limited recent evidence on preventive approaches to eradicate IOM. In 1988, a Ugandan study adopted informative radio broadcasts and education within the antenatal departments at the hospitals to emphasise the complications associated with IOM. However, the number of infants brought to the hospitals with IOM increased in the following years, indicating that the parents may be better equipped to identify the complications associated with IOM; merely education was not sufficient to prevent IOM from taking place. Even though this strategy was helpful in reducing the fatality rate stemming from IOM, other strategies may be valuable in conjunction to educational campaigns.35 Another study based in Uganda (2006)37 explored the effectiveness of educational programmes by measuring the IOM-related hospitalisation numbers. The programme involved role-plays, lectures and debates and was executed with 23 women's groups in 15 different communities. A few years following the completion of the programme, a reduction in IOM-related complications was reported. This community-based programme involved the community in the design and implementation of the programme, emphasising the importance of collective responsibility and sustainability of such programmes to eradicate IOM. Furthermore, this study concluded that interventions targeting mothers were cost-effective.37 Finally, the dental officer of Tororo, Uganda introduced a harm-reduction approach in their report by underlining the need to educate the healers on methods of sterilisation and extractions, IOM-associated complications and infection control. This led to an increase in appropriate referrals to trained dental professionals for extractions and use of sterile herbal medicine at the site of IOM.38

Current efforts to eradicate IOM involve both education and advocacy. Dental students at the Muhimbili Dental School in Tanzania have recommended a community-based approach to eradicating IOM. Their recommendations include training dentists and dental nurses on debunking myths related to IOM for their patients, as well as collaborating with the Ministry of Health on addressing this important public health issue.39 However, educating healthcare professionals may not be as effective, as some individuals may not have access to a healthcare provider to benefit from their knowledge. Additionally, organisations such as the Global Infant Dental Fund, the World Federation of Public Health Associations, the Paediatric Dental Association of East Africa and others, are also creating awareness and advocating for the eradication of IOM globally.40 In 2019, the Addis Ababa Declaration by the Global Child Dental Fund invited the dental community to support the chief dental officers of East and Central Africa to eradicate IOM within ten years.41 End IOM (https://www.endiom.org/)and Bridge2aid (https://bridge2aid.org/) are two of the organisations currently working to eradicate IOM on the frontlines. At present, there are no reports of the progress made to date since the Declaration. It is likely that the efforts to eradicate IOM were impacted by COVID-19, similarly to other programmes implemented to address FGM,42 malaria43and obesity44 among others. Amid a global pandemic, financial and human resources may be redirected to fighting the virus and other important health issues may be pushed aside.

Based on current evidence, eradication of IOM globally requires a multifaceted and multisectoral approach. Strategies that involve the community in the design, implementation and evaluation of programmes are deemed more effective and sustainable in the long term. Moreover, empowering parents, mothers and fathers alike to understand the harms associated with IOM and protect their infants from such practices is critical. Lastly, implementing public health interventions that address other determinants of health, such as access to clean water and sanitation, may also help the parents in addressing common childhood diseases, such as diarrhoea and vomiting, that are usually a precursor to IOM.

Conclusion

While concentrated in East Africa, IOM affects individuals in many parts of the world. However, through clinical training of health professionals, alongside routine data collection, IOM and its consequences can be managed and reported better, with the ambition to end the practice altogether. The data collection tool, described above, can be used by health professionals to identify and report a suspected IOM case. The consistent reporting of IOM cases is critical, especially in areas where an IOM-trained dental professional may not be readily available. Such reporting will also identify where interventions are most needed. With such interventions and public health-based approaches, the myths that contribute to IOM can be debunked and the morbidity and mortality associated with the practice can be reduced and eventually eradicated. To conclude, routine data collection, timely clinical care and context-specific interventions embedded in education, community involvement and empowerment, alongside advocacy and knowledge sharing, are needed to tackle IOM globally.

Appendix 1 IOM data collection tool. Section 1-3 to be completed for all patients; section 4a/4b based on each individual case

References

Accorsi S, Fabiani M, Ferrarese N, Iriso R, Lukwiya M, Declich S. The burden of traditional practices, ebino and tea-tea, on child health in Northern Uganda. Soc Sci Med 2003; 57: 2183-2191.

Dentaid. Dentaid Impact Document for IOM. Available at https://www.dentaid.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Dentaid-impact-document-for-IOM.pdf (accessed November 2022).

Abusinna I M. Lugbara teeth germectomy of canines for the newborn babies. A magico-religious phenomena in some African tribes. Egypt Dent J 1979; 25: 209-214.

Matee M I, van Palenstein Helderman W H. Extraction of ‘nylon' teeth and associated abnormalities in Tanzanian children. Afr Dent J 1991; 5: 21-25.

Mugonzibwa E A, Kahabuka F K, Mwalutambi S C, Kikwilu E N. Current status of nylon teeth myth in Tanzania: a cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2018; 18: 9.

Girgis S, Cheng L. Infant oral mutilation: A response to the subject - ‘Infant oral mutilation'. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 161.

Garve R, Garve M, Link K, Türp J C, Meyer C G. Infant oral mutilation in East Africa - therapeutic and ritual grounds. Trop Med Int Health 2016; 21: 1099-1105.

Nuwaha F, Okware J, Hanningtone T, Charles M. False teeth “Ebiino” and Millet disease “Oburo” in Bushenyi district of Uganda. Afr Health Sci 2007; 7: 25-32.

Girgis S, Gollings J, Longhurst R, Cheng L. Infant oral mutilation - a child protection issue? Br Dent J 2016; 220: 357-360.

Pope E A, Roberts M W, LaRee Johnson E, Morris C L. Infant Oral Mutilation. Case Rep Dent 2018; DOI: 10.1155/2018/7586468.

Holan G, Mamber E. Extraction of primary canine tooth buds: prevalence and associated dental abnormalities in a group of Ethiopian Jewish children. Int J Paediatr Dent 1994; 4: 25-30.

Iriso R, Accorsi S, Akena S et al. ‘Killer' canines: the morbidity and mortality of ebino in northern Uganda. Trop Med Int Health 2000; 5: 706-710.

Rodd H D, Davidson L E ‘Ilko dacowo:' canine enucleation and dental sequelae in Somali children. Int J Paediatr Dent 2000; 10: 290-297.

Khonsari R H, Corre P, Perrin J-P, Piot B. Orthodontic consequences of ritual dental mutilations in northern Tchad. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 67: 902-905.

Amailuk P, Grubor D. Erupted compound odontoma: case report of a 15-year-old Sudanese boy with a history of traditional dental mutilation. Br Dent J 2008; 204: 11-14.

A/Wahab M M. Traditional practice as a cause of infant morbidity and mortality in Juba area (Sudan). Ann Trop Paediatr 1987; 7: 18-21.

Graham E A, Domoto P K, Lynch H, Egbert M A. Dental injuries due to African traditional therapies for diarrhoea. West J Med 2000; 173: 135-137.

Davidovich E, Kooby E, Shapira J, Ram D. The traditional practice of canine bud removal in the offspring of Ethiopian immigrants. BMC Oral Health 2013; 13: 34.

Jones A. Tooth mutilation in Angola. Br Dent J 1992; 173: 177-179.

Hassanali J, Amwayi P, Muriithi A. Removal of deciduous canine tooth buds in Kenyan rural Maasai. East Afr Med J 1995; 72: 207-209.

De Beavis F O V, Foster A C, Fuge K N, Whyman R A. Infant oral mutilation: a New Zealand case series. N Z Dent J 2011; 107: 57-59.

Dewhurst S N, Mason C. Traditional tooth bud gouging in a Ugandan family: a report involving three sisters. International J Paediatr Dent 2001; 11: 292-297.

Barzangi J, Unell L, Söderfeldt B, Bond J, Musse I A, Arnrup K. Infant dental enucleation in an East African population in Sweden: a cross-sectional study on dental records. Int J Paediatr Dent 2014; 24: 209-214.

Dinur N, Becker T, Levin A et al. Long-term dental implications of infant oral mutilation: a case series. Br Dent J 2021; 231: 335-340.

Kikwilu E N, Hiza J F. Tooth bud extraction and rubbing of herbs by traditional healers in Tanzania: prevalence, and sociological and environmental factors influencing the practices. Int J Paediatr Dent 1997; 7: 19-24.

Hiza J F, Kikwilu E N. Missing primary teeth due to tooth bud extraction in a remote village in Tanzania. Int J Paediatr Dent 1992; 2: 31-34.

Hassanali J, Amwayi P. Report on two aspects of the Maasai dentition. East Afr Med J 1988; 65: 798-803.

Kemoli A, Gjørup H, Nørregaard M-L M et al. Prevalence and impact of infant oral mutilation on dental occlusion and oral health-related quality of life among Kenyan adolescents from Maasai Mara. BMC Oral Health 2018; 18: 173.

Waldman H B, Kemoli A M, Rader R, Perlman S P. Disabilities and superstition: infant oral mutilation. 2019. Available at http://reader.mediawiremobile.com/accessibility/issues/205494/articles/5dc1924250fcc301dfbccead/reader (accessed November 2022).

Wandera M N, Kasumba B. “Ebinyo” - The Practice of Infant Oral Mutilation in Uganda. Front Public Health 2017; 5: 167.

Edwards P C, Levering N, Wetzel, E, Saini T. Extirpation of the primary canine tooth follicles: a form of infant oral mutilation. J Am Dent Assoc 2008; 139: 442-450.

Musinguzi N, Kemoli A, Okullo I. Prevalence and dental effects of infant oral mutilation or Ebiino among 3-5-year-old children from a rural district in Uganda. BMC Oral Health 2019; 19: 204.

Rakhshan V. Congenitally missing teeth (hypodontia): A review of the literature concerning the aetiology, prevalence, risk factors, patterns and treatment. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2015; 12: 1-13.

EndIOM. What is IOM? Available at https://www.endiom.org/what-we-do (accessed November 2022).

Stefanini A. Influence of health education on local beliefs: incomplete success, or partial failure. Trop Doct1987; 17: 132-134.

World Health Organisation. Promoting Oral Health in Africa: Prevention and control of oral diseases and noma as part of essential noncommunicable disease interventions. 2016. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/205886/9789290232971.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed November 2022).

Jamieson L M. Using qualitative methodology to elucidate themes for a traditional tooth gauging education tool for use in a remote Ugandan community. Health Educ Res 2006; 21: 477-487.

Kirunda W. ‘Ebino' (False Teeth): How the Problem was Tackled in Tororo. Trop Doct1999; 29: 190.

Kahabuka F K. The ‘Nylon teeth myth'. Tanzania Dent J 2007.

Global Child Dental Fund. Eradicate Infant Oral Mutilation (IOM). Available at https://www.gcdfund.org/our-work/eradicate-infant-oral-mutilation-iom (accessed November 2022).

Wordley V, Bedi R. Infant oral mutilation in East Africa: eradication within ten years. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 14-15.

United Nations Population Fund and United Nations Children's Fund. COVID-19 Disrupting SDG 5.3: Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation. 2020. Available at https://www.unfpa.org/resources/covid-19-disrupting-sdg-53-eliminating-female-genital-mutilation (accessed November 2022).

Zawawi A, Alghanmi M, Alsaady I, Gattan H, Zakai H, Couper K. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on malaria elimination. Parasite Epidemiol Control 2020; DOI: 10.1016/j.parepi.2020.e00187.

Senthilingam M. Covid-19 has made the obesity epidemic worse, but failed to ignite enough action. BMJ 2021; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.n411.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for our colleagues working on the frontlines tackling IOM, who emphasised the need for a data collection tool and clinical management guidelines in their communities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zoha Anjum led the literature review, analyses and manuscript writing. Gemma Bridge and Raman Bedi contributed to manuscript preparation and provided mentorship to Zoha Anjum in drafting this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anjum, Z., Bridge, G. & Bedi, R. Infant oral mutilation: data collection, clinical management and public health guidelines. Br Dent J 233, 1042–1046 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-5317-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-5317-0