Abstract

Introduction The children and young people who utilise hospice services often have additional oral health care needs and may present with additional challenges in regard to mouth care. Hospice colleagues need support and would benefit from national direction in providing mouth care for this important group.

Methods Questionnaires were provided to hospice nursing colleagues, parents and carers to assess current knowledge and confidence around mouth care and diet. An audit was also completed on hospice records to assess the recording of mouth care provision prior to the introduction of Mini Mouth Care Matters. Training was then provided to colleagues in the form of a virtual interactive learning session and a re-audit of hospice records was then completed.

Results Almost 30% of colleagues had never received mouth care training and two-thirds of colleagues faced barriers in providing daily mouth care. Overall, 11% of children who accessed hospice services had never visited a dentist and nearly half of the children brushed less than twice a day. The Mini Mouth Care Matters assessment tool resulted in an increase in assessment of the mouth of children using the hospice, along with early identification of problems and improving daily mouth care.

Conclusion Mini Mouth Care Matters is transferable to children's hospices and should be extended to all children's hospices nationally.

Key points

-

As dentistry emerges from COVID-19, a truly multidisciplinary approach to paediatric oral health is required to support the profession. Mini Mouth Care Matters in children's hospices details a way that this can occur.

-

The expansion of Mini Mouth Care Matters beyond the hospital environment shows that it is applicable to other settings and could also potentially expand further.

-

This paper illustrates the need for national policy relating to oral health in children's hospices and that there is a need for increased oral health education during nursing training and throughout postgraduate development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Statistics from Public Health England in 2019 revealed that 23% of five-year-olds had experience of dental decay and the average number of teeth with decay was 3.45.1 Dental decay in children and young people (CYP) can often lead to extraction under general anaesthetic; there were 44,685 extractions of multiple teeth in under-18s under general anaesthetic in England in 2018/19, at a cost of £41.5 million.2 Certain groups of CYP are more at risk of developing mouth-related problems due to medical, cognitive or physical disabilities; this includes CYP with autism spectrum disorder, ventilated patients and palliative care patients. Some studies have shown little difference in the prevalence of decay between disabled and non-disabled children3 but in disabled children, it is more likely to remain untreated4 and be more complex to manage. This group of children will often utilise hospices and poor oral health can negatively impact their quality of life. For some of these children, a general anaesthetic could be life-threatening, therefore targeted prevention is essential.

There are 45 children's hospices in England which provide care for CYP who have life-threatening or life-limiting conditions and associated complex needs.5 Care is provided both within the hospice and at home as part of the outreach provision. Services include therapeutic and psychosocial support, short-stay breaks, emergency care and end-of-life care (EOLC). A 2020 study showed that the number of children in England requiring palliative care increased between 2001 and 2018 from 26.7 per 10,000 to 66.4 per 10,000.6 Not only does this group require more active support than their peers but the number of children within the group is growing. It is also already recognised that children from more deprived backgrounds are more likely to experience dental decay. However, a 2014 study showed that there was a higher prevalence of children with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions in areas of higher deprivation.7

Colleagues in children's hospices are therefore in a position to improve the oral health-related quality of life of these CYP. Very often, the colleagues responsible for delivering the necessary care have had little general mouth care training, let alone specific training for this important and unique group. Studies show that the training nursing colleagues receive in relation to mouth care is variable and the initial training received by healthcare assistants does not include mouth care.8,9

This paper reports a service evaluation undertaken by Mini Mouth Care Matters10 (Mini MCM) in conjunction with Acorns Hospices11 in the Midlands. Acorns operate from three sites in Selly Oak, Walsall and Worcester. Their hospice in Selly Oak opened on 14 December 1988 and the other sites opened in 2000 and 2005, respectively. The three sites employ 90 care staff, which is comprised of nurses, healthcare assistants and family team workers. During 2020, 740 children were supported across the three sites.

Mini MCM is a training initiative aimed at improving the oral health of hospitalised paediatric patients in England. Initially funded by Health Education England in 2019, it has been rolled out to 37 trusts nationally. The original aim of Mini MCM was to 'empower medical and allied medical healthcare professionals to take ownership of the oral health care of any paediatric in-patient with a hospital stay of more than 24 hours'. It has done this through face-to-face training and appointing hospital leads to collate baseline data on mouth care, implement change and re-evaluate mouth care practices. Mini MCM is now the agreed term for when non-dental professionals are asked to engage with a CYP's oral health. The aim of this project was to determine the knowledge of nursing teams within a children's hospice and the carers of those CYP who use the service. Through carrying out a quality improvement project to develop mouth care, the aim was to investigate whether the Mini MCM programme should be recommended for a wider implementation to children's hospices.

Method

This service evaluation was supported by Acorns Children's Hospices in the Midlands. Acorns Hospices were looking to develop their mouth care provision and contacted the lead for Mini MCM for support. Approval was sought from Acorns Hospices Research and Development team for cooperation and the project was registered with the hospice. NHS ethics approval was not required as the project was a service evaluation rather than research. A pilot questionnaire was formulated based on the Mouth Care Matters and Mini MCM hospital questionnaires.12 The questionnaire contained 12 questions for colleagues which were either multiple choice or free-format answers (Appendix 1). The questions sought to ascertain the level of previous mouth care training and colleague confidence in providing different aspects of mouth care, such as for CYP with an unsafe swallow, or a persistently dry mouth. A question was also asked about confidence in recognising common oral conditions noted within this population, including caries, oral ulceration and candida. The pilot was completed by five hospice colleagues, amendments were made and an electronic version of the questionnaire was sent to all hospice colleagues involved in mouth care. A second questionnaire was formulated for parents and carers. This questionnaire contained 17 questions and looked to ascertain current mouth care routines, diet and a basic dental history, including last dental attendance and any history of dental treatment. The participants consented to participate and to have their data used as part of the project and publication.

A baseline audit was also completed on mouth care practices in the hospices. This audit gathered information on whether an initial mouth care assessment was completed, whether any oral problems were documented, if mouth care was provided, and if so, which mouth care tools were used. The results from the two questionnaires and audit allowed the Mini MCM hospice team (which consisted of three dental core trainees and a consultant in paediatric dentistry) to construct a training module which was delivered virtually due to COVID-19 restrictions. Although this module was designed for Acorns Hospices, the aim was for it to be adaptable to children's hospices nationally. The training was delivered via an interactive two-hour session covering results from the questionnaires, common oral conditions, how to provide mouth care for CYP using the hospice and case-based scenarios. A further audit of hospice records was then carried out two months after training had been disseminated.

Results

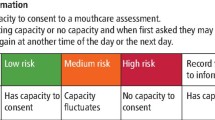

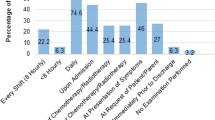

The colleague questionnaire was completed by 67 colleagues from a potential 90; 74.6% (n = 50) were nursing colleagues and the remainder were healthcare assistants and physiotherapists. However, 28.4% (n = 19) of colleagues had never had training in providing mouth care. For those who had received training, 61.2% (n = 30) were provided with in-house training and 49% (n = 24) received training as part of their initial nursing training. The questionnaire asked colleagues if a toothbrush and toothpaste were provided where CYP had not brought them to the hospice. Although 83.6% (n = 56) of colleagues checked if the CYP had brought a toothbrush and toothpaste, 23.4% (n = 15) said that these items were not always available to provide. Almost two-thirds (n = 42) of colleagues identified barriers to providing mouth care (Fig. 1). Although 97% (n = 65) felt confident in brushing teeth, 29.8% (n = 20) did not feel confident brushing the teeth of those who displayed challenging behaviour. The majority of colleagues felt confident at recognising a range of common oral conditions (Fig. 2) but did not feel confident in discussing them, including providing oral health advice or advising on how to find a dentist (Fig. 3).

The parents and carers of 73 CYP who utilised Acorns Hospices completed the questionnaire. Only 16.4% of CYP (n = 12) had attended the dentist within the last six months and 28.8% (n = 21) within the last year. Of note is the fact that 11% (n = 8) had never visited a dentist. This questionnaire was completed in March 2021, so it was therefore asked if the COVID-19 pandemic had impacted their child's dental attendance and 82.2% (n = 60) of respondents felt there had been an impact. When asked about dental treatment, 17.8% (n = 13) of parents advised their child had undergone restorative dental work or extractions, either under local or general anaesthetic. Dental problems can also lead to difficulty eating and drinking and this was the case for 15.1% (n = 11) of CYP. Nearly half of parents (n = 32) advised that toothbrushing happened less than twice per day and for those who did brush (n = 51), 50.9% (n = 26) rinsed after brushing. Only 37% (n = 27) of parents were able to confirm that the medications their child took were sugar-free and the same number (n = 27) were not sure.

Baseline audit records were also analysed. Ten records were retrospectively assessed for CYP who had utilised hospice care staying overnight. The ages of the CYP ranged from 1-16 and there was an equal split between sexes. On admission, 80% (n = 8) had not had a mouth care assessment or a record of any mouth-related problems. However, 70% (n = 7) had a record of having mouth care completed in the previous 24 hours but only 40% (n = 4) had any details recorded, such as products used.

After the above information was obtained, a virtual training session was provided for colleagues of the hospices in April 2021. This session was provided by three dental core trainees with the support of a consultant in paediatric dentistry. The training covered elements of the Delivering better oral health toolkit13 (DBOH), including how to ask about dental history, diet advice and oral hygiene advice, especially for those displaying challenging behaviours. Feedback was then sought from those who attended the session. All feedback was positive and the attendees felt it helped them with providing mouth care. This session was attended by 16 colleagues, with the intention that the knowledge and skills gained could then be cascaded through to other colleagues. The education team at Acorns already had mouth care on their agenda and had also put together a supplementary programme of online mouth care learning for their team, including topics such as anatomy of the mouth.

A second cycle of 35 records was assessed in June 2021. Two parents in this sample refused mouth care provision for their children. In this cycle, 94.2% (n = 33) of CYP had a mouth care assessment completed on arrival at the hospice and 85.7% (n = 30) had documentation of whether they had any mouth-related problems. Removing the two children whose parents refused mouth care provision by the hospice, 90.9% (n = 30) received mouth care in the previous 24 hours and 84.8% (n = 28) had a record of what mouth care products were used. Figure 4 shows a direct comparison between results from before and after training.

Discussion

This project shows that Mini MCM is directly transferable to children's hospices and can have a positive impact on the mouth care provided and colleague knowledge. There is little research on oral care in the end-of-life paediatric population. However, prevalence of debilitating oral conditions is high in this group;14,15 many of which have a profoundly negative impact on overall wellbeing. Expanding Mini MCM into this important care setting allows for an additional group of healthcare professionals to help 'put the mouth back in the body' through mouth care assessments, identification of dental disease and provision of mouth care. It also provides family support in the form of toothbrushing and advice, which can have far-reaching impact on mouth care practices at home.

Mouth care assessment

The Mini MCM mouth care assessment tool11 allows a comprehensive assessment of a CYP's mouth. The assessment tool begins with basic questions of whether the CYP has teeth, a dentist, any orthodontic appliances or dentures and whether they have brought a toothbrush and toothpaste with them. These questions are then followed by a visual examination of the oral cavity which will allow visualisation of any oral health-related problems which need addressing. This is not a means by which any diagnosis can be made but simply to identify any obvious problems. Enquiring about dental attendance provides an opportunity for the hospice colleague to recommend regular dental visits, promote Dental Check by One (DCBy1)16 and deliver key, evidence-based prevention messages. In the absence of the Mini MCM assessment tool, no initial oral health assessments were carried out by staff for CYP utilising the hospice. However, once integrated, 94% of CYP benefited from an oral assessment. This represents a significant cohort who may benefit from early detection and prevention.

It is important for all healthcare professionals to be aware of and discuss DCBy1. The DCBy1 campaign, promoting dental attendance before a child's first birthday, can be promoted by any healthcare professional and could have greater reach when promoted by healthcare professionals outside a dental environment. However, these questionnaire results indicated that colleagues were not confident in discussing dental attendance or advising about access. A 2008 study of nursing staff working in paediatric cancer care revealed a lack of awareness with regards to dental referrals and procedures for patients undergoing stem cell and cancer treatment.17 One study suggests that lack of parental awareness is a major contributory factor for low dental attendance in children who have a learning disability.18 The significant impact of a child with a long-term, life-limiting medical condition should also be considered as a potential barrier to regular dental visits.19 Support in this area from hospice colleagues could therefore have a positive impact and the training provided as part of this project included how to approach this topic with families in a sensitive manner. The COVID-19 pandemic has also impacted the nation's dental attendance. NHS dental attendance figures published in February 2021 show that over two-thirds of children (70.2%) in England did not see an NHS dentist in the 12 months to 31 December 2020.20 Similarly, 82.2% of parents in this service evaluation reported that COVID-19 had impacted their child's dental attendance.

Finding out whether a CYP has brought a toothbrush and toothpaste to the hospice allows for these essential items to be provided where necessary. Without this simple question, mouth care may not be carried out for a prolonged period as the family may not ask for them. These results also show that these items are not necessarily always available. As the CYP using these services will also likely often require specialist mouth care, including non-foaming toothpaste or toothbrushes with different heads, these products may be difficult to source for hospices, thereby rendering mouth care even more challenging. Figures from 2019 show that children's hospices receive only 21% of their funding from the state5 and lack of funding has meant some hospices have had to cut services. Provision of appropriate mouth care products is therefore an area where national support could be beneficial.

Mouth care in the hospice and oral health advice

The results from the mouth care records show improvement in the number of CYP receiving mouth care. However, the goal was also to improve colleague confidence and knowledge. CYP in a hospice are likely to have additional needs and challenges when providing mouth care, meaning specific training for these colleagues is key. Indeed, 77.6% of those undertaking our staff questionnaire felt they would benefit from training in providing mouth care and assessing the mouth. As part of this, standardising the care provided to children using hospices is important to ensure that out-of-date practices are not encouraged. For example, the use of foam swabs carries aspiration risks.21 Best practice is therefore to avoid their use, yet it is something which is still found in many settings. Studies have shown that mouth care training is often received early on in a nursing career (if at all) and regular updates do not necessarily occur.9,22

Research has also been carried out on barriers for nursing colleagues providing mouth care in hospitals. These barriers include lack of training, time, knowledge and assessment tools.23,24 An article in 2018 found similar barriers in an adult hospice setting.25 However, there is little literature from paediatric settings. This survey correlates with these hospital and adult hospice findings. Furthermore, a 2013 study assessing oral health perceptions of paediatric palliative care nursing staff perceived child and family resistance to mouth care as two major barriers to its provision.19 Paediatric hospice colleagues in the questionnaire stated that parents have specifically asked for their child's teeth not to be brushed. Confidence to question further around this is therefore imperative. If this barrier can be overcome, mouth care can be a way to build trust with the family, as the study by Couch et al. reported.26

Many of the CYP requiring hospice care will be oncology patients. Drug therapy and radiation will often adversely impact the oral health of these children.27 Studies of paediatric oncology patients show that the most effective means of preventing and treating pain from oral complications is through meticulous systematic oral care.14 Interestingly, a study from 2000 states that although a patient or family member can often perform oral care, it is the responsibility of palliative nursing staff to see that the care is provided.17,28 The goal of high quality EOLC is to ensure that the child is able to live as well as possible and to ensure that their needs and those of their family are identified and met.7 Mouth care is a key aspect of this. Research also shows that caring for a CYP at the end of their life is emotionally challenging and traumatic,29 yet as already discussed, training is limited. The training provided by Mini MCM encompassed all of these elements to develop colleague knowledge and confidence.

Survey results revealed just over half of CYP brush at least twice daily and over one-third rinse after brushing. This means there is plenty of room for oral hygiene improvement in line with the DBOH toolkit.13 According to a study published in the British Dental Journal, getting children to brush their teeth was a source of stress for many families.30 The study showed 46% of parents have worries about their child's teeth as a result of trying to get them to brush. This does not take into consideration the additional factor of medically compromised children, which potentially exacerbates concerns. There are a number of studies which have investigated the impact of a 'brushing reminder' through an app notification or text.31,32 For busy parents of medically compromised children, this could be a useful tool recommended by hospice colleagues. The DBOH toolkit also recommends sugar-free medication; however, 57.5% of survey respondents reported the medication their child requires contains sugar or they did not know the sugar content. Many of the medications these children take are lifesaving and do not come in sugar-free formulations. Therefore, it is even more important that appropriate mouth care occurs.

Consideration needs to be given to the limitations associated with the methodology of this service evaluation. Firstly, there is limited high-quality evidence and research on the topic of mouth care of CYP in hospice care. The baseline audit looked at ten records only. This is a small sample size and there is a risk that it may not accurately reflect overall record-keeping for the hospices involved. However, the retrospective records were difficult for the hospice to access and it was therefore necessary to accept a small sample size. Future audits would therefore benefit from being completed prospectively. The baseline audit also focused on records from Acorns Hospices only, rather than a range of hospices, which may have different policies and protocols. The staff questionnaire was answered by 67 staff members, out of a potential 90. This demonstrates a 74% respondent rate. In contrast, 73 parents and carers of children who utilise hospice care out of a potential 740 responded to the second questionnaire. This sample demonstrates less than 10% of the overall focus group. However, the basis of this service evaluation was to highlight the need for a nationally directed programme on mouth care for this group of children and provide a baseline for work with further hospices.

Conclusion

Acorns Hospices have now adopted a formal process for mouth care, demonstrating that change is achievable at local level. A nationally directed oral health care plan for children's hospices has the potential to positively influence the oral health-related quality of life of this complex and vulnerable group, while also alleviating some of the notable burden of paediatric dental need within the NHS.

Mini MCM is symbolised by Elwood the elephant: elephants never forget and mouth care is something all healthcare professionals should never forget. The mouth needs to be put back in the body, no matter what the healthcare setting is.

Change history

14 October 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-5094-9

References

UK Government. Oral health survey of five-year-old children 2019. 2020. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/oral-health-survey-of-5-year-old-children-2019 (accessed July 2021).

WiredGov. LGA: Nearly 180 operations a day to remove rotten teeth in children. 2020. Available at https://www.wired-gov.net/wg/news.nsf/articles/LGA+Nearly+180+operations+a (accessed January 2021).

Gizani S, Declerck D, Vinckier F, Martens L, Marks L, Coffin G. Oral health condition of 12-year-old handicapped children in Flanders (Belgium). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997; 25:352-357.

Pope J E, Curzon M E. The dental status of cerebral palsied children. Paediatr Dent 1991; 13: 156-162.

Together for Short Lives. Children's Hospice Services. Available at https://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/get-support/supporting-you/family-resources/childrens-hospice-services/ (accessed July 2021).

Fraser L K, Gibson-Smith D, Jarvis S, Norman P, Parslow R C. Estimating the current and future prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Palliat Med 2021; 35: 1641-1651.

Norman P, Fraser L. Prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children and young people in England: time trends by area type. Health Place 2014; 26:171-179.

Adams R. Qualified nurses lack adequate knowledge related to oral health, resulting in inadequate oral care of patients on medical wards. J Adv Nurs 1996; 24:552-560.

Doshi M, Mann J, Quentin L, Morton-Holtham L, Eaton K A. Mouth care training and practice: a survey of nursing staff working in National Health Service hospitals in England. J Res Nurs 2021; 26: 574-590.

Health Education England. e-lfh Mini Mouth Care Matters. Available at https://portal.e-lfh.org.uk/myElearning/Index?HierarchyId=0_57494_57494& programmeId=57494 (accessed September 2022).

Acorns Children's Hospice. About Acorns. Available at https://www.acorns.org.uk (accessed January 2021).

Health Education England. e-lfh Mouth Care Matters. Available at https://portal.e-lfh.org.uk/myElearning/Index?HierarchyId=0_50050&programmeId=50050 (accessed September 2022)..

UK Government. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2021. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/delivering-better-oral-health-an-evidence-based-toolkit-for-prevention (accessed November 2021).

Belfield P M, Dwyer A A. Oral complications of childhood cancer and its treatment: current best practice. Eur J Cancer 2020; 40:1035-1041.

Allerton L A, Welch V, Emerson E. Health inequalities experienced by children and young people with intellectual disabilities: a review of literature from the United Kingdom. J Intellect Disabil 2011; 15: 269-278.

British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. Dental Check by One. Available at https://www.bspd.co.uk/patients/dental-check-by-one (accessed July 2021).

Tewogbade A, FitzGerald K, Prachyl D, Zurn D, Wilson C. Attitudes and practices of nurses on a paediatric cancer and stem cell transplant ward: adaptation of an oral care protocol. Spec Care Dentist 2008; 28: 12-18.

Lo G L, Soh G, Vignehsa H, Chellappah N K. Dental service utilization of disabled children. Spec Care Dentist 1991; 11: 194-196.

Simons D, Pearson N, Dittu A. Why are vulnerable children not brought to their dental appointments? Br Dent J 2015; 219: 61-65.

NHS Digital. NHS Dental Statistics for England 2020-21, Biannual Report. 2021. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-dental-statistics/2020-21-biannual-report (accessed November 2021).

UK Government. Oral swabs with a foam head - heads may detach during use. 2014. Available at https://www.gov.uk/drug-device-alerts/medical-device-alert-oral-swabs-with-a-foam-head-heads-may-detach-during-use#:~:text=Problem-,Foam%20heads%20of%20oral%20swabs%20may%20detach%20from%20the%20stick,head%20could%20not%20be%20retrieved (accessed November 2021).

Talbot A, Brady M, Furlanetto D L C, Frenkel H, Williams B O. Oral care and stroke units. Gerodontology 2005; 22:77-83.

Gibney J, Wright C, Sharma A, Naganathan V. Nurses' knowledge, attitudes, and current practice of daily oral hygiene care to patients on acute aged care wards in two Australian hospitals. Spec Care Dentist 2015; 35: 285-293.

Costello T, Coyne I. Nurses' knowledge of mouth care practices. Br J Nurs 2008; 17:264-268.

Soileau K, Elster N. The Hospice Patient's Right to Oral Care: Making Time for the Mouth. J Palliat Care 2018; 33: 65-69.

Couch E, Mead J M, Walsh M M. Oral health perceptions of paediatric palliative care nursing staff. Int J Palliat Nurs 2013; 19: 9-15.

Levy-Polack M P, Sebelli P, Polack N L. Incidence of oral complications and application of a preventive protocol in children with acute leukemia. Spec Care Dentist 1998; 18: 189-193.

Gillam J L, Gillam D G. The assessment and implementation of mouth care in palliative care: a review. J R Soc Promot Health 2006; 126:33-37.

Maunder E Z. Emotion work in the palliative nursing care of children and young people. Int J Palliat Nurs 2006; 12: 27-33.

British Dental Journal. Many British parents say children not brushing teeth long enough. Br Dent J 2018, 225: 469.

Underwood B, Birdsall J, Kay E. The use of a mobile app to motivate evidence-based oral hygiene behaviour. Br Dent J 2015; DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.660.

Marshman Z, Ainsworth H, Chestnutt I G et al. Brushing RemInder 4 Good oral HealTh (BRIGHT) trial: does an SMS behaviour change programme with a classroom-based session improve the oral health of young people living in deprived areas? A study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2019;20: 452.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gemma Williams, Clinical Practice Educator and the rest of the team at Acorns Children's Hospices for their support with this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Charlotte Schofield, Reuben Bennett, Courtney Orloff and Urshla Devalia contributed to the development and delivery of hospice training and manuscript review and editing. Additionally, Charlotte Schofield carried out the data collection, primary analysis and drafting of the manuscript; Reuben Bennett developed the final figures for the manuscript; and Urshla Devalia conceived the project and oversaw its planning and execution.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

NHS ethics approval was not required as the project was a service evaluation utilising existing Mini Mouth Care Matters approved processes and tools rather than research. The participants in this study consented to participate and to have their data used as part of the project and publication.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised.

When this article was originally published, DCBO was used throughout to denote 'Dental Check by One' but should have read DCBy1. This has since been corrected.

In addition, an incorrect version of Figure 3 was displayed. The correct figure is presented here, in which the x-axis has been updated.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schofield, C., Bennett, R., Orloff, C. et al. Children's hospices: an opportunity to put the mouth back in the body. Br Dent J (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-4926-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-4926-y