Abstract

Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic has had a large impact on dentistry across Wales. Dentists were facing significant levels of psychological distress prior to the pandemic, so it was important to monitor dentists' mental health during this unprecedented challenge.

Aims To gain both an understanding of the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has been having on the mental health of dentists working in Wales, as well as understanding the levels of stress the pandemic has caused. We also aimed to understand the specific causes of stress.

Results High levels of stress were found, with 82% of respondents saying stress levels in the dental team have increased noticeably. Three-quarters of respondents have gone to work despite not feeling mentally well enough. Working conditions and financial pressures caused by the pandemic have directly impacted the mental health of many dentists. As a result, they have been using both adaptive and maladaptive coping methods to cope with the stress of the pandemic, with over one-third of respondents drinking alcohol more frequently than before the pandemic.

Conclusions The pandemic has had a profound impact on the professional lives of dentists working in Wales. Their interactions with patients and colleagues have been greatly affected, as well as their work and working conditions. These have all substantially contributed to increased stress levels. Without significant improvements to the working conditions of dentists, as well as continued psychological support, large-scale burnout in the future is not only possible, but likely.

Key points

-

Provides detailed information of the stressors dentists dealt with during the pandemic and looks at how many dentists cannot cope with the stress of their job during the pandemic.

-

Looks at the maladaptive coping methods dentists have used over the course of the pandemic, such as alcohol and nicotine products, as well as the adaptive coping methods dentists have used, such as walks and mindfulness.

-

Discusses how many dentists went to work despite not feeling mentally well enough to do so, plus looks at the impact the pandemic has had on dentists' sleep.

-

Looks at the working conditions dentists in Wales are facing due to the pandemic and the way different aspects of dentistry have been affected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Overview

This study aimed to gain both an understanding of the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has been having on the mental health of dentists working in Wales, as well as understanding the levels of stress the pandemic has caused. We also aimed to understand the specific causes of stress. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a large impact on dentistry across Wales and almost all aspects of the profession have been affected. Workloads have significantly changed, as well as the way patients can be treated. The pandemic has also affected dentistry differently as it has progressed. The Welsh government's pandemic red phase massively impacted the work of community dental service (CDS) dentists who set up and treated patients in urgent dental care and who continue to do so. It also greatly changed the day-to-day work of the general dental services (GDSs) and created financial concerns for dental practices as businesses. In particular, private dentistry was financially impacted with very limited relief from any government schemes. Redeployment within the NHS has also taken place throughout the pandemic and public health dentistry had to focus on the pandemic with oral health programmes being suspended since March 2020. At the time of writing, 18 months on from the start of the pandemic and seven months since the survey was completed, dentistry is still operating within the Welsh government's pandemic low amber restrictions, with continuing enhanced infection control measures causing limits on patient throughput. Practices and clinics have also had to adapt to the various changes COVID-19 has brought; from enhanced personal protective equipment (PPE) becoming the norm, to the need for minimum air changes and fallow periods following aerosol generating procedures. Increased requirements for decontamination have also become routine. However, there is nothing normal or routine about dentistry in a pandemic and we heard many anecdotes of how working conditions were affecting the stress levels and morale of dentists and their teams in both the GDS and CDS. We decided a full investigation was needed in order to highlight the longer-term effects of the pandemic and altered working conditions on dentists' mental health. Data on dentists' mental health over the course of the pandemic were limited. However, the British Dental Association's Health Assured Service saw a 575% rise in calls for counselling. This study aimed to gather essential data on the mental health of dentists in Wales to uncover the extent of the problem so it could be addressed.

Introduction

Mental health wellbeing, as well as stress and burnout, is being increasingly studied and discussed in dentistry. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, depression and anxiety in the general population had increased in recent years1 and the British Dental Association (BDA) had begun investigating the stress dentists feel professionally. The 2019 BDA paper on stress and burnout in UK general dental practitioners (GDPs) discovered high levels of self-reported stress, with 43% of dentists stating they could not cope with the stress in their job.1 Almost one-fifth (17.6%) admitted they had seriously thought about suicide.2

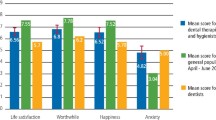

The recent BDA Health Assured data had shown an increase in use during the pandemic. The percentage of calls for counselling increased by 575% from September 2019 to July 2020 (Fig. 1). While Health Assured could not break these calls down nationally, dentists in the UK are using this service more.

Some research had been carried out early in the pandemic regarding the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and wellbeing of dentists. In May 2020, an online survey by the BDA collected demographic data, levels of psychological distress and experiences from UK dentists during the 'national lockdown' period of the pandemic. This survey found that GDPs in England, (who were the most populous respondents to the survey and remotely working during this time), valued the time away from the surgery.3 Others found the conditions stressful, facing previously acknowledged stressors, alongside novel stressors the pandemic has created.3 While that study found psychological distress was lower in UK dentists during the national lockdown period when compared to previous research using the same measure, this can be attributed to the time interval when the study took place. Dentists in the English GDSs were not performing face-to-face care at that time, but working remotely and not experiencing the day-to-day stressors of dentistry. This survey found that further research would be vital to monitor the ongoing and sustained effects this pandemic has had on dentists' mental wellbeing, especially when the stressors of performing face-to-face care were reintroduced.3 The study report also stated that despite the findings, psychological distress in dentists remained high in comparison to other professions.4 As dentistry in Wales has changed significantly since March 2020, with the de-escalation of the pandemic alert level from red to amber in Wales beginning in July 20205 and concomitant changes to the clinical standard operating procedure (SOP), the impact of the pandemic on dentists' mental health will likely have changed over time.

A survey on the psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on staff in a dental teaching hospital found high anxiety levels and significant psychosocial implications among dental staff during this virus pandemic.6 The British Dental Journal team had also published a paper about tackling mental health as a team during the pandemic.7 A study on depression and anxiety in UK frontline health and social care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic found that care workers without reliable access to PPE were more likely to meet criteria for a clinically significant mental disorder (Table 1).8 Studies, alongside anecdotal reports from dentists in Wales, suggested that stress levels had significantly increased for dentists during the COVID-19 pandemic. The baseline data before the pandemic suggested that there were already high levels of stress in the profession.2 The specific challenges that the pandemic has brought and continues to bring would likely have affected this.

Method

The data for this study were gathered through a survey of dentists working in Wales (Table 2). A cross sectional survey design was utilised. The survey was piloted by the committee members of the three BDA Wales committees; the Welsh Council, Welsh Committee for Community Dentistry and Welsh General Dental Practitioner Committee.

The survey was launched on 21 January 2021. It was highlighted in the member newsletter to Welsh Dentists and featured on the BDA website. A solus email was sent to 645 members and 443 non-members on 27 January 2021 and again on 6 February 2021. The survey received 132 responses, resulting in a response rate of 12%. This response rate was within the target range of 10-15%, which is common for surveys on mental health and is a 3% improvement in uptake compared to the 2018 UK-wide BDA stress and burnout survey.

SmartSurvey was used to design the survey. SmartSurvey also anonymised the data from the survey, with dentists providing a code to ensure that the survey was GDPR-compliant and that they could withdraw their data if they wished. There were no participants who wished to withdraw their responses. Participants were also informed of the purpose of the survey and how their data would be used.

All participants gave their express consent to participate in the study and to have their data used as part of the research. Hyperlinks to support organisations were listed before and on completion of the survey.

Measures of stress were taken from existing scales developed by Cooper et al.18 Coping methods were measured using a five-point or six-point Likert-type scale, with participants indicating whether they were utilising methods 'more frequently', 'without change' or 'less frequently' than before the pandemic.

Results

Stress experienced during the pandemic

The first section of the survey focused on the stress dentists have experienced in and because of their professional lives during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interpretation of these data should be made with caution due to the shift in perception that the pandemic has created in many individuals. What may have been deemed as highly stressful before the pandemic may be seen as relatively less stressful due to the perceived stressful circumstances of others and the stresses COVID-19 has brought to daily life outside of work.

Dentists were believed to have high potential occupational exposure to COVID-19, second only to medical practitioners.19,20 As a result, the early stages of the pandemic saw the cessation of routine dental care and the creation of urgent dental centres (UDCs) in Wales.21 Of the 132 survey participants, 14% (19) stated they had been redeployed during the pandemic, with 4% (5) remaining redeployed at the time of completing the survey. Two-thirds of those redeployed worked in UDCs. Other dentists were redeployed to administrative duties, critical care and COVID-19 testing. Some dentists were unable to work due to their circumstances during the pandemic. Over one-third of dentists redeployed to a UDC found this extremely stressful, with 91% (115) finding the experience at least moderately stressful. Sleep was also greatly affected, with 78% (13) of respondents who worked in a UDC rating their quality of sleep as bad or very bad. A study on depression and anxiety in UK frontline health and social care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic found that being redeployed during the pandemic and having had COVID-19 were associated with higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder.5

Carrying out NHS work had also been stressful for dentists in Wales, with over half of respondents finding this to be 'extremely stressful' or 'very stressful'. The needs of the patients being treated caused similar levels of stress. A study of English GDPs also showed that NHS work was a stressor for dentists, with over 40% stating it was likely or extremely likely that they would reduce their personal NHS commitment in the next 12 months.22

Treating patients and managing their expectations was cited as a large source of stress. Patient backlog was a concern to dentists, as well as managing patient expectations. Treating only urgent cases had an impact on dentists' mental health. Patients' health and wellbeing was also a source of stress for dentists, with almost one-third of respondents concerned for patients' needs and 7% (9) cited their stress of dealing with patient expectation. Enforcing safe practice during the pandemic had also caused stress.

Levels of stress in the dental team were discussed by participants. A quarter of respondents mentioned staff, with many concerned for their mental well-being. There was a clear disconnect in some practices between management and staff. Some practice managers felt that their guidance was continuously questioned when they were trying to 'keep staff safe, sometimes from themselves'.

Some respondents were concerned about contract reform and the next financial year. Multiple respondents felt that contract reform was being forced through.19 Some respondents felt that they needed more training with Assessment of Clinical Oral Risks and Needs (ACORN) forms. One respondent suggested an online national conference so that they could 'fully get behind' the reform. Respondents wanted more evidence to show contract reform's benefits. Others cited the need for more guidance and information. ACORN forms, which are an element of contract reform, were chosen to be utilised as part of the pandemic measures in NHS dentistry. This seems to have left some survey participants confused, resulting in them believing they had joined the contract reform programme, despite repeated clarification that this was not the case.

General and private dental practices are businesses as well as healthcare providers. This means that for associates and owners, finances are also a source of stress. Of those who worked in a practice, 43% (39) reported they were 'extremely stressed' about their practice's finances.

To determine whether the amount of stress experienced by dentists during the pandemic exceeded their ability to cope, dentists were asked to state the level of agreement to the following question: 'I can cope with the level of stress in my current job.' If respondents stated that they disagreed with this statement to some degree ('strongly disagreed', 'disagreed' and 'somewhat disagreed') this was taken as they could not cope with the stress in their job. Almost half of dentists (43%, 54) reported that they could not cope. Compared with the 2018 BDA Stress and Burnout survey,2 the percentage of dentists who disagreed extremely strongly that they could cope with their job has more than doubled and now stands at 12% (15). As previously discussed, the pandemic has caused a shift in perception on what it means to be stressed and what it means to cope. Making a direct comparison to before the pandemic should be done with caution.

A survey conducted by the Dental Defence Union found that 49% of the dentists who responded felt that they were unable to do their jobs effectively.24 This survey was conducted in the early stages of the pandemic, with the results being published in July 2020. It is concerning that nine months later in early 2021, a very similar number of 43% of dentists could not cope with the level of stress in their job (Fig. 2).

Lifestyle changes during the pandemic

The lifestyle changes dentists made during the pandemic showed the impact it had on their mental health. Both adaptive and maladaptive coping methods were looked at. Adaptive strategies promote long-term wellbeing and focus on ways of reducing stress, encompassing both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping. Maladaptive coping strategies typically can help to reduce stress in the short-term but do not promote long-term benefits.25 Avoidance, self-criticism, procrastination, drug and alcohol misuse and venting are all examples of maladaptive coping strategies.

The survey looked at both the duration and quality of sleep. Prior to the pandemic, 90% of dentists were getting either 6-8 or 8-10 hours of sleep. Only 7% (9) stated they slept between 4-6 hours a night. During the pandemic, dentists' sleep has drastically decreased. Just 11% (15) received 6-8 hours of sleep. There was a rise of almost one-third in those sleeping 4-6 hours, rising to 36% (48). Studies have found that getting only five hours sleep per night for four nights in a row negatively affected mental performance to a similar extent as having a blood alcohol content of 0.067. It can also affect mood and result in low productivity.26

Sleep quality for many dentists was also impacted. The charts in Figure 3 show a significant fall in sleep quality with almost two-thirds of dentists stating their sleep was 'bad' or 'very bad' during the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, 0% of dentists said their sleep quality was 'very bad'; during the pandemic, this had risen to 18%. Over 80% of dentists thought the pandemic had impacted the quality or duration of their sleep.

Dentists were asked about their activity levels before and during the pandemic. Exercise has been identified as being a popular coping strategy employed by dentists in dealing with stress.27 Prior to the pandemic, two-thirds of dentists were meeting or exceeding the recommended exercise levels. During the pandemic, over half were not achieving the recommended exercise levels, with 11% (14) doing no exercise. There was a 20% (27) drop in those meeting or exceeding the recommended 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity. There was a further reduction of one-fifth (15) of participants who were able to meet the recommended 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity.

Participants were also asked about their social media usage over the course of the pandemic. Social media can be both a positive and negative coping mechanism. There is a plethora of research on the positive and negative effects it can have on a user's mental health, but that remit is outside of this research. The survey found that 93% (123) of respondents used social media. Of these respondents, 63% (83) stated that they were using social media more than before the pandemic. It is unclear from the survey data whether this had an overall positive or negative effect, but some individuals have reported that, early on in the pandemic, social media was helpful and they found support in those social spaces, whereas later they were becoming quite toxic. As a result, some dentists withdrew from them.28

Alcohol usage was also looked at (Fig. 4). Results showed that 40% (52) of dentists were drinking alcohol more frequently than before the pandemic; this was the most reported description of alcohol use during the pandemic. Dentists may be using alcohol as a maladaptive coping strategy to deal with the stress of the pandemic. Studies have shown that in those communities where alcohol use is normal, alcohol has been used by the public as a coping mechanism over the course of the pandemic.29

Dentists were asked about prescribed or over the counter drugs or natural substances that are mood enhancers. Over one-third of dentists who used mood enhancing products were using them more frequently than before the pandemic. Use of prescribed or over the counter painkillers had increased for 21% (27) of dentists during the pandemic.

Of those dentists who use nicotine products, including cigarettes, e-cigarettes and cigars, almost two-thirds stated that they used them more frequently than before the pandemic. This figure is concerning and is not in keeping with trends in the public. A recent survey conducted by smoking cessation charity Action on Smoking and Health suggests that more than one million people have given up smoking since the COVID-19 pandemic, while University College London found more people quit smoking in the year of June 2020 than in any year since its survey began in 2007.30 It is concerning that among dentists who use nicotine products, there has been a significant increase in usage.

It should be noted that, where applicable and with the exception of alcohol, none of the respondents found themselves using substances less than before the pandemic.

Adaptive coping methods such as going for walks, practising yoga, gardening and meditation were used by 80% (101) of respondents to cope with the stress of the pandemic. It is also reassuring that dentists stated other positive changes they had made, such as reducing alcohol consumption and starting counselling. Some participants expanded on why they had not made positive changes to cope with stress.

Participants were asked whether they had had to shave their beard for PPE fit testing. Over one-third of dentists, who felt this question applied to them, had to shave their beard for PPE fit testing. While the need to shave for PPE fit testing is unavoidable, it is important to note the impact it has on a dentist's mental health and sense of identity. Participants also communicated that it was a visual reminder of the pandemic.

Dentists' working conditions during the pandemic

The working conditions of dentists during the pandemic were asked about. Questions looked at whether dentists were able to take breaks, redeployment, access to PPE and staff morale.

Perhaps due to an increase in PPE required, 31% (40) of dentists stated they were never able to fit in short rest and refreshment breaks in the morning and afternoon. One dentist shared 'when I went back to work in July [there were] no breaks whatsoever and [we were] in full PPE all session'. Many dentists commented on a rise in administrative tasks and time needed for triaging. Where breaks were available to be taken, dentists commented this due to a patient cancellation.

Over one-third of dentists were unable to take at least half an hour lunch break most working days. Dentists stated that meetings and triage calls often took up their lunch breaks. This resulted in 88% (116) of dentists stating they often or sometimes ate at their desk during their lunch break.

Over the course of the pandemic, concerns around PPE have been widely reported, with dentists voicing their concerns.31 The survey asked dentists in Wales about their access to PPE over the course of the pandemic. While almost half of participants said their practice/clinic struggled to access PPE in earlier stages of the pandemic, nine months later 8% (11) continued to struggle to access PPE. The comments regarding PPE were varied. Some participants praised their Health Boards' management of PPE, while others stated the out-of-date PPE the Health Board had supplied had failing straps. This is particularly concerning as inadequate PPE can adversely affect mental health in addition to risking infection.32 Fears for personal safety and a loss of trust in suppliers have been apparent since the early stages of the pandemic.33 Many associates stated they had to purchase their own PPE and others commented that cost and quality were still an issue. The price of surgical gloves and face masks had reportedly increased from £3.50 a box to upwards of £30. Inability to access good-quality PPE contributed to an already stressful working environment, particularly in the early stages of the pandemic.

A recent BDA survey of GDPs in England found that working in high-level PPE was damaging to morale.22 Almost all dentists (90%) dentists stated that working in high-level PPE was having a highly negative impact on morale. Dentists in England found it more impactful than financial uncertainty and hitting NHS targets.22

Participants were also asked about patient backlog (Fig. 5). Three-quarters of respondents (95) were very concerned about the levels of patient backlog. Most respondents (96%, 127) had at least some concern. The quality of oral health of the public was a concern highlighted by some respondents. One dentist commented that they were already 'seeing patients with multiple problems', while another was concerned that patient needs would become more complex due to the pandemic. There was a particular concern for general anaesthetic procedures, as well as sedation services and special care.

Multiple dentists also shared that patient backlog was a concern alongside contract reform. The need to see a minimum number of new patients was a source of stress when most patients had 'not had an examination in over a year'. One dentist queried how it would be possible to catch up on the backlog of patients while treating new patients, adding 'please don't [say] skills mix. There is only a minimal amount nurses and hygiene/therapists can do'. The inclusion of new patients while facing a large patient backlog was also a daunting prospect for many GDPs.

Dentists were also asked about testing positive for COVID-19 and having a COVID-19 vaccination. While only 6% (8) of dentists stated they had tested positive for COVID-19, 61% (81) of dentists stated that staff members or colleagues had tested positive. Others commented that staff had had to isolate due to family members. One dentist stated that half of the staff tested positive, resulting in the practice closing for two weeks. As well as stress caused by fearing they would contract the virus, dentists also must contend with the stress of other members of staff contracting the virus.

While 91% (116) of dentists had received the COVID-19 vaccine, one-third (3) of those had not felt stressed that they had not yet been vaccinated. Multiple individuals stated their concern regarding the length of time between the two vaccines administration and the impact this would have on the vaccination's efficacy.

Stress within the dental team had risen, with 83% (109) of respondents stating that stress levels in the dental team had increased noticeably. Participants shared that staff were physically and mentally exhausted. Fear of contracting COVID-19 was cited as a reason for increased stress. The treatment of staff by patients was also a cause of stress. One participant shared 'the levels of stress and anxiety with our staff is unprecedented. I have had issues with staff actively obstructing efforts [to] increase levels of patient care and coming up with spurious reasons not to interact with patients. Especially with aerosol generating procedures'.

Participants were asked approximately how many days they had gone into work during the pandemic despite not feeling mentally well enough (Figures 6 and 7). Three-quarters of respondents had done this. Furthermore, more than half of respondents in this group had done so for more than ten days. This is an extremely worrying figure. These results show an increase from the 2018 survey on mental health and burnout, where just under half of respondents in Wales had gone to work despite not feeling mentally well enough.

Other studies have shown that, from the early stages of the pandemic, dentists have been going to work despite not feeling mentally well enough. The Dental Defence Union (DDU) survey found that in the early months of the pandemic, 47% of dentists often went to work when they did not feel well.8 It is concerning that not only has this problem continued, but it has become worse. While the DDU did not provide a definition for what constitutes 'often', 52% of dentists had gone to work despite not feeling mentally well enough for more than ten days.

Access to support

Dentists were asked about their access to support, what help they were aware of and what provision they had accessed.

Nearly half of dentists felt there were barriers that prevented them from discussing their stress levels with their line manager. Just over one-third of dentists felt they were able to talk to their manager about their stress levels. Confidentiality was a commonly cited barrier; one dentist had observed their line manager discussing a colleague and feared being discussed as weak. One dentist cited concerns that discussing their stress levels would affect their pay. Other dentists cited a lack of empathy, understanding or interest from their manager. Some dentists said that their manager was never there.

A further concern was the stress that line managers were under themselves. Multiple dentists stated that their managers were busy and stressed. One dentist stated that their manager was 'under even more stress and I don't want to burden them'. Managers stated that their stress levels were high, one commented that they did not 'feel there's anywhere to go for support'. While there is a clear issue with a lack of support from management in dentistry, there was also a lack of support for management.

While 70% (89) of dentists stated that they were aware of mental health services available to them, only 18% (25) named any mental health services. Occupational health was cited frequently, as well as Denplan. Confidental, Mental Dental and the Health Board were also listed. The BDA was the most common support service mentioned and one dentist stated that they discovered Health Assured due to the survey and would likely try it. Accessibility to support offered by the Health Board was deemed poor by one dentist. Of the 9% (11) of respondents who had accessed mental health support services, the most common form was counselling.

Only 4% (5) of respondents had taken time off work due to stress since the pandemic began, even though three-quarters of respondents had gone to work despite not feeling mentally well enough. Multiple respondents felt they could not take time off work due to stress. One respondent queried how they could take time off for stress when they were running a business. Dentists have not taken time off despite not feeling mentally well enough, increasing the risk of burnout. The 2018 Stress and Burnout Survey found that 10% of participants from Wales had taken time off for mental health reasons in the previous year. It is concerning that despite the fact more participants felt that they were not mentally well enough to work, fewer respondents had taken any time off.

Multiple respondents stated the difficulty of seeing a general practitioner (GP) during the pandemic, while others felt there was 'little point in contacting them' as they believed GPs could not refer them to counselling and could only prescribe antidepressants. Consequently, only 9% (11) of respondents had been diagnosed by a GP with stress, anxiety or depression during the pandemic. Other respondents stated that they were trying to cope without seeing a GP. Results showed that 10% (13) of respondents were taking medication for stress, anxiety or depression. One respondent had declined a prescription for antidepressants.

Community dental service

The CDS changed rapidly during the pandemic and many CDS clinics became UDCs. Data from respondents working in the CDS showed that the change in their work had led to grave concern for the vulnerable patients they normally treat. The survey found that 88% (15) of respondents working in the CDS felt very concerned about the level of their patient backlog. One respondent stated that their waiting list was now a year longer. Respondents shared the impact that the pandemic had had on all aspects of community dentistry in Wales. One respondent stated that 'all services that [the CDS] offer have been affected: GA, sedation, domiciliary and general special care clinic'. Another respondent did not see how the CDS could ever catch up.

Results showed that 94% (16) of respondents reporting stress levels in CDS dental teams had increased noticeably. One respondent disclosed their impression that 'everyone is coping but that's what we all want everyone else to think'. Anecdotal reports previously suggested that hidden stress was a problem within the CDS. The survey has confirmed this. Almost all respondents (94%, 16) working in the CDS had gone to work despite not feeling mentally well enough during the pandemic.

Respondents in the CDS were less likely than their counterparts in the GDS to speak to their line manager, with 63% (10) of respondents feeling unable to speak to their manager. This figure may, in truth, be higher, as 92% (13) of respondents in the CDS reported barriers that prevented them from speaking to their line manager. Just under one-fifth of respondents working in the CDS had accessed mental health support over the course of the pandemic.

Despite high levels of stress and a great majority not feeling mentally well enough to work, none of the respondents working in the CDS had taken time off due to stress during the pandemic. It is also concerning that 47% (8) of CDS respondents had gone to work despite not feeling mentally well enough for more than ten days. These data show that even when mental wellbeing is consistently poor for CDS dentists, they still feel unable to take time off work. This unaddressed and prolonged stress will likely result in high levels of burnout in the future. Burnout can develop when someone is under stress for a prolonged period and in a state of emotional, physical and mental exhaustion, which the results show dentists in Wales are experiencing.36

General dental service

Patient care was a large source of stress for dentists working in the GDS. Limited time slots and fallow times caused stress. Multiple GDP respondents stated that patients had been rude to them. One participant elaborated that more needed to be done by the Welsh Government to inform patients as to why fewer NHS appointments are available.

Sleep quality and the negative impacts it creates is also a concern for practitioners in the GDS. Almost two-thirds of GDP respondents rated their sleep quality as bad or very bad. One survey participant stated they stay awake worrying about money for the future. Multiple respondents stated they wake in the night or struggle to sleep due to worrying about work. One-third of GDPs had gone to work for more than ten days during the pandemic when they did not feel mentally well enough. Finances and the future of dentistry were large sources of stress for GDPs who were concerned over the finances of their practice, with 90% (49) stating so. Uncertainty and concerns over the reform of the NHS contract were also a source of stress for some respondents. Among some GDPs, there was a lack of understanding about the contract reform programme and a desire to be included further.

General dental practice owners

Finances were a large source of stress for general dental practice owners. Over half were extremely stressed by the finances of their practice, while 93% (53) were at least moderately stressed. One practice owner shared that they had 'virtually lost all my income with no help, no grants, no furlough, nothing'. Contract reform and uncertainty regarding the contract, was also a source of stress for practice owners.

Data also showed a concerning lack of support for practice owners and managers. One respondent stated that as a practice owner 'of a very small practice, I have never felt so alone'. Managing staff and staff stress levels also caused considerable stress for practice owners. Almost one-fifth (10) of practice owners strongly disagreed that they could cope with the level of stress in their job, while almost half felt they could not cope. Three-quarters of practice owners rated their quality of sleep as very bad or bad during the pandemic.

One practice owner shared that they have felt helplessness over the course of the pandemic, stating that they wanted to answer staff's questions when they were unable to. As well as dealing with the stress of the pandemic as a practitioner, practice owners also felt responsible for their staff.

Practice owners are facing the stresses of being business owners during the pandemic, as well as being health care providers. It is clear that these combined stresses are affecting the mental wellbeing of practice owners. A study in the early stages of the pandemic found that practice owners reported significantly greater psychological distress (65%) compared to associates (55%).3 It is therefore likely that practice owners would have faced significant psychological distress throughout the pandemic and continue to do so.

Finances have been a huge source of stress for practice owners and GDPs in other countries. A study of dentists in Germany found that participants considering the pandemic a financial threat reported significantly higher scores on both The Impact of Event Scale-Revised and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 scales.23 This study also found that dentists who stated that they worked in other facilities showed lower psychological distress than their colleagues in dental practices.7 The financial implications of working at, or owning, a dental practice during the COVID-19 pandemic have had a negative impact on stress levels.

Sex and age

All respondents were asked which sex they identify with. Over half of respondents identified as women, 40% identified as men, 1% (1) identified as intersex and 1% (1) preferred not to say.

Data showed that the levels of stress experienced were often reported as higher by women. Finding an experience to be 'moderately stressful' was the most common response among male participants, while 'extremely' or 'very stressful' was the most common response among women. Female respondents were three times more likely to access support than their male counterparts.

Data also showed that Health Boards often did not provided PPE that fitted female staff properly. One respondent stated that their Health Board 'only send medium/large gloves - which is no good for most female nurses and dentists. So, we have to buy our own anyway.' The August 2020 Survey by The Health and Care Women Leaders Network found that 21% of the female NHS workers surveyed did not have access to the PPE they needed.37 Respondents also stated that staff were wearing gowns in size extra-large, when most required a small or medium.25 Despite 77% of the NHS workforce identifying as women, there was a clear problem with official supplies of PPE not being suitable for them. This is an example of institutional/systemic discrimination. Discrimination is a known contributor to poorer mental health in women38 and likely an additional stressor for female dentists.

Respondents were asked to indicate their age using the following age brackets: 18-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54 and over 65. Dentists in the 18-24 age bracket had the lowest levels of stress among the age brackets.

Respondents in the age bracket 45-54 were most likely to state that an experience was extremely stressful. Working during the red alert was the most stressful experience for dentists in this age bracket. Over 60% (24) of respondents found NHS work 'extremely stressful' or 'very stressful'. Finances of the practices was also a large source of stress, with over half of respondents deeming this 'extremely stressful' or 'very stressful'. Over 40% (18) of respondents could not cope with the level of stress in their job.

Dentists in the age bracket 25-34 were the least likely to take a break, with just 6% (1) able to take breaks often and 35% (6) never able to. Respondents in the age bracket 35-44 were most likely to never able to take at least a half hour lunch break, with 15% (4) stating this. This may contribute to why all respondents felt they could cope with the level of stress in their job. The age bracket 25-34 had the most respondents going to work despite not feeling mentally well enough, with 94% (16) doing so for at least one day. This age bracket also saw the highest number of participants going to work for more than ten days despite not feeling mentally well enough, with 47% (8) doing so.

Commentary

Survey response rate

Response rates for surveys of this nature are often between 10% and 30%. The Care Quality Commission's (CQC's) mental health survey response rate was 27% in 2019 and has been a similar figure for the last three years.39 The BDA Stress and Burnout Survey had a response rate of 9%.2 The recent BDA survey on psychological distress and the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK dentists during a national lockdown had a response rate of 12%.3 While the response rate of the survey was in keeping with previous surveys, the findings should be viewed with caution as there is a risk of participant bias.

Perception of stress during the pandemic

As previously stated, the pandemic has created a shift in perception in terms of stress. The exceptional circumstances seem to have impacted the respondents' view of stress and the way they perceive and report it. Previous research determined that some individuals may experience 'denial' or running on 'auto-pilot' while working during the pandemic.40,41 This is particularly clear when individual responses are looked at. Here are three such examples. One individual agreed they could cope with the current level of stress in their job, yet they stated they were drinking alcohol more frequently and found themselves waking up during the night, unable to get back to sleep which 'did not happen pre-COVID-19'. Another participant agreed they could cope, yet also stated they were drinking alcohol more frequently and stayed up at night worrying about staff and finances. Finally, a respondent working in the CDS found several aspects of working during the pandemic to be only mildly stressful and did not agree or disagree with the statement 'I can cope with the level of stress in my job'. However, they also stated that they re-lived their days at work instead of sleeping and that they had gone to work for more than ten days during the pandemic despite not feeling mentally well enough. The impact of this stress continuing unaddressed could result in future post-traumatic stress symptoms, burnout and increased psychological distress.42

Mind, the mental health charity, found that a third of adults did not access support because they did not think that their issue was serious enough.43 They also found the key challenge was to ensure those who want to access services know that they deserve support.28 Several survey participants stated felt that 'others have it worse' and that they needed to 'suck it up' or 'get on with it'. Respondents were also more likely to discuss the severity of stress among their colleagues rather than their own. Multiple respondents stated that their line manager lacked empathy, with one stating that their manager felt that they 'signed up to be health professionals so should get on with it'. Dentists may struggle to feel that their mental health problems are valid during the pandemic.

It is difficult to examine these data in comparison with wider research. Several studies have determined that psychological support is vital for health professionals,34 with one study determining that mental health support was at least as important as physical protection for dentists during the COVID-19 pandemic.35 However, there is a lack of research on the uptake of psychological support during the pandemic.

Changes during the pandemic

While the BDA study of psychological distress in May 2020 was populated mostly by English GDPs,3 it still provides an interesting point of comparison for dentist's stress levels during the pandemic. The study found a 10% drop in the number of dentists who exceeded the clinical threshold for psychological distress, though the figure still sat at 58%. However, Collin et al. found that common themes in the reasons for this. Multiple respondents stated that they enjoyed the break from dentistry while working remotely,3 allowing them to mentally recharge. Since July 2020, GDPs in Wales have returned to dental practices, while CDS dentists have largely treated patients face-to-face throughout the pandemic. Some dentists also stated that there had been a lack of pressure from the NHS, patients, GDC, CQC and GDPR.3 The resumption of face-to-face care meant that these pressures had returned, alongside further pressures relating to the pandemic. It is clear that there were significant differences in dentistry from May 2020 to January 2021 and Collin et al. stated the importance of continued research into the impact the pandemic on dentist's mental health.3

In contrast, in Wales, practices were never completely closed as they remained open for urgent care for low-risk patients. Results showed that dentists in Wales have faced abuse from patients since the pandemic restrictions eased from red to amber alert levels, with some patients unwilling to follow COVID-19 guidelines. One participant shared 'lots of the staff (are) on the edge and very tearful. Abuse from patients about waiting outside, wearing masks, waiting times'. As the pandemic continues, with pressures and stressors continuing to evolve, it is vital that research into the mental health of dentists continues.

Loneliness

Lockdown and social distancing resulted in an increase of loneliness among the public. The Mental Health Foundation found that a quarter of people (25%) reported feeling lonely in the previous two weeks.44 Dentistry has often been described as a lonely profession. The results of this survey show that the pandemic brought another layer of isolation into this. One associate described having to eat lunch alone in their car every day, while another respondent stated that loneliness is a source of stress during the pandemic. One practice owner stated that as the owner of a small practice, they had never felt so alone.

The amber standard operating procedure for dentistry and the impact on mental health

The SOP for the dental management of non-COVID-19 patients in Wales, that was current at the time of the survey, had been in place since December 2020, reflecting the Welsh government's low amber alert status for dentistry, which remains at the time of writing. Separate SOPs were used at centres for people with suspected/confirmed COVID-19. Several aspects of the SOPs were reported as a source of stress. One dentist commented that there was a lack of clarity over the air filtration in their practice and they did not know how many air changes were taking place or if they met the ten per hour that the SOP required. Another dentist stated that their main stress was patient expectations with their reduced working capacity due to the SOP. Fallow periods have had a large impact on working capacity and dentists had not been informed as to when this was likely to change. Some practitioners stated frustration that they had not been consulted by the Welsh government regarding the SOP's development.

Enhanced personal protective equipment and the impact on mental health

Enhanced PPE and duration of wear was cited as a source of stress by 15% (4) of respondents. Dentists cited pain in their necks, backs and shoulders due to stress and increased PPE and shared that they found it difficult to work in. One respondent found the enhanced PPE reasoning 'sometimes illogical'. Problems with enhanced PPE were also raised in the section on working conditions during the pandemic. One respondent stated that in July 2020 they were in enhanced PPE all session with 'no breaks whatsoever'.

A study published in the European Journal of Dentistry investigated COVID-19 PPE-induced headaches.45 The survey found that while healthcare workers with previous history of pre-existing headaches were found to be more susceptible to PPE-induced headaches, their age and the department where the healthcare workers performed could also be risk factors.

A further study on heat stress and PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic had been conducted in the UK, which looked at the impact on healthcare workers' performance, safety and wellbeing in NHS settings.46 The study found that 60% of health care workers involved stated that PPE affected their attentional focus. The study also investigated health care workers' experiences of heat stress. Just over three-quarters of respondents reported PPE impaired their physical performance at work. The study also focused on the items of PPE individually and the main issues healthcare workers experience with them. Some health care workers highlighted that wearing PPE increased the severity of symptoms associated with menopause such as hot flushes.34 The SOP has not changed, in terms of the level of PPE required, since the red alert stage of the pandemic.

On 4 June 2021, the four UK chief dental officers issued a statement confirming that a further review of the UK-wide infection control guidance (SOP) in the light of the current science and prevalence would take place.47 No doubt this was in response to the successful roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccination programme, which had not commenced at the time of the survey. This is a potential positive step that could greatly improve the conditions for dentists working in Wales. However, at the time of writing, a new SOP remains awaited.

Recommendations

The findings from this study support the following recommendations which would not only benefit patients but would likely have materially positive effects on dentists' stress levels:

Capacity and backlog of care need

-

The Welsh government must consider changes to the SOP, particularly in terms of reducing the need for enhanced PPE and reduction in fallow times when treating COVID-19-negative patients. This is realistic since the full rollout of the COVID-19 vaccination programme

-

The Welsh government and Health Boards must consider the impact that the expectation of practices to see new patients will have on an already large backlog of GDS patients

-

The Welsh government and the Health Boards must look at ways to address the backlog of CDS patients in Wales, starting with investing in overhauling the ventilation systems in all surgeries to reduce fallow times.

Planning with certainty

-

The Welsh government and Health Boards must offer further information on the future of dentistry in Wales for business planning. For example, a return to 100% contract value for all practices that are performing within the normal expectation ranges. A clear vision for the scope of NHS dentistry in Wales is needed

-

The Welsh government should continue to offer clear communication and increased involvement for practices regarding contract reform well in advance of April 2022.

Managing stress

-

The Welsh government and the Health Boards must provide training, funding and accessible, professional support. For example, allowing all dental workplaces in primary and secondary care to have a team member trained and supported as a mental health first aider if they so wish

-

The Welsh government should also provide stress awareness training for dentists, while continuing to allow Welsh dentists access to Health for Health Professionals

-

The BDA should carry out further research into the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of dentists in Wales and the potential longer-term and wider impacts of their mental health on their relationship with dentistry, especially NHS dentistry. The BDA will continue to share the findings with Welsh government.

Conclusion

The pandemic has had a profound impact on the professional lives of dentists working in Wales. Their interactions with patients and colleagues have been greatly affected, as well as their work and working conditions. Dentists continue to feel a significant sense of uncertainty regarding the future of dentistry, with high levels of stress caused by patient backlog and finances.

The working conditions dentists have faced over the course of the pandemic have been a significant cause of stress. Further research is needed into the effects that extended PPE has had on the mental health of dentists. This would be particularly pertinent to dentists experiencing menopause. The administrative responsibilities of dentists have also increased during the pandemic, which has resulted in dentists taking significantly fewer breaks. Dentists are also continuing to work despite not feeling mentally well enough, most for significant periods of time.

The recently published Mental Wellness Framework in Dentistry references the adverse effect the COVID-19 pandemic would have had on stress levels and emphasises the importance of putting mental health awareness at the centre of the dental workplace.48 It is vital that change takes place within dentistry so that dentists' mental health and wellbeing are supported.

If the working conditions for dentists during the pandemic continue to go unchanged, dentists' mental wellbeing is likely to erode; the results of which would be devastating. Access to NHS dentistry in Wales was worsening for new adult patients before the pandemic. This has been worsened during the pandemic due to the focus on emergency dental treatment, as well as the barriers the SOP creates. While safety precautions must be in place to protect both dentists and patients, it is vital that they are proportionate. Without significant changes to the working conditions of dentists, large scale burnout in the future is not only possible, but likely.

References

Bulman M. Anxiety and depression among UK workers up nearly a third in four years, figures show. The Independent (London) 2017 October 10.

Toon M, Collin V, Whitehead P, Reynolds L. An analysis of stress and burnout in UK general dental practitioners: subdimensions and causes. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 125-130.

Collin V, O´Selmo E, Whitehead P. Psychological distress and the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK dentists during a national lockdown. Br Dent J 2021; DOI: 10.1038/s41415-020-2592-5.

Fritischi L, Morrison D, Sirangi A, Day L. Psychological well-being of Australian veterinarians. Aust Vet J 2009; 87: 76-81.

Welsh Government. Restoration of Dental Services post COVID-19: De-escalation of RED Pandemic Plan. 2020. Available at https://awfdcp.ac.uk/content/files/Restoration-of-Dental-Services-post-Covid-19-de-escalation-of-RED-pandemic-plan.pdf (accessed June 2021).

Mahendran, K, Patel, S, Sproat C. Psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on staff in a dental teaching hospital. Br Dent J 2020; 229: 127-132.

Elnaqa F. You are not alone. BDJ Team 2020; 7: 35.

Greene T, Harju-Seppänen J, Adeniji M et al. Predictors and rates of PTSD, depression and anxiety in UK frontline health and social care workers during COVID-19. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2021; DOI: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1882781.

Lexico. Stress. Available at https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/stress (accessed June 2021).

Lexico. Stressor. Available at https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/stressor (accessed June 2021).

Lexico. Mental Health. Available at https://www.lexico.com/definition/mental_health (accessed June 2021).

World Health Organisation. Depression: definition. 2021. Available at https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases/pages/news/news/2012/10/depression-in-europe/depression-definition (accessed June 2021).

American Psychology Association. Anxiety. 2021. Available at https://www.apa.org/topics/anxiety/ (accessed June 2021).

Medical Dictionary. Psychological Distress. Available at https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/psychological+distress (accessed June 2021).

Dimitriu M, Pantea-Stoian A, Smaranda A C et al. Burnout syndrome in Romanian medical residents in time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Hypotheses 2020; DOI: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109972.

Taylor S. Coping Strategies. 1998. Available at https://macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/coping.php (accessed June 2021).

Tull M. What Is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder? 2021. Available at https://www.verywellmind.com/ptsd-in-the-dsm-5-2797324 (accessed June 2021).

Cooper C L, Watts J, Baglioni Jr A J, Kelly M. Occupational stress among general practice dentists. J Occup Psychol 1988; 61: 163-174.

Office for National Statistics. Which occupations have the highest potential exposure to the coronavirus (COVID-19)? 2020. Available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/whichoccupationshavethehighestpotentialexposuretothecoronaviruscovid19/2020-05-11 (accessed November 2021).

Gamio L. The Workers Who Face the Greatest Coronavirus Risk. The New York Times (New York) 2020 March 15.

Johnson D. Coronavirus: Progress and urgent dental centres in Wales. 2020. Available at https://www.bda.org/news-centre/blog/coronavirus-progress-and-urgent-dental-centres-in-wales (accessed June 2021).

British Dental Association. Where is dentistry's roadmap? 2021. Available at https://bda.org/news-centre/blog/Pages/Where-is-dentistrys-roadmap.aspx (accessed June 2021).

Mekhemar, Mohamed et al. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Dentists in Germany. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 5 1008.

GDPUK. Stress and anxiety levels have increased since the pandemic - DDU survey. 2020. Available at https://www.gdpuk.com/news/latest-news/3626-stress-and-anxiety-levels-have-increased-since-the-pandemic-ddu-survey (accessed June 2021).

Wadsworth M E. Development of Maladaptive Coping: A Functional Adaptation to Chronic, Uncontrollable Stress. Child Dev Perspect 2015; 9: 96-100.

Barnes C M, Drake C L. Prioritizing Sleep Health: Public Health Policy Recommendations. Perspect Psychol Sci 2015; 10: 733-737.

British Dental Association. The mental health and well-being of UK dentists: A qualitative study. 2017. Available at https://bda.org/about-the-bda/campaigns/Documents/The%20Mental%20Health%20and%20Well-being%20of%20UK%20Dentists.pdf (accessed December 2021).

British Dental Association. Wales: Mental Health in a time of crisis. 2021. Available at https://bda.org/news-centre/blog/Pages/Wales-Mental-health-in-a-time-of-crisis.aspx (accessed December 2021).

Sallie S N, Ritou V, Bowden-Jones H, Voon V. Assessing international alcohol consumption patterns during isolation from the COVID-19 pandemic using an online survey: highlighting negative emotionality mechanisms. BMJ Open 2020; DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044276.

Schraer R. Coronavirus: Smokers quit in highest numbers in a decade. BBC (London) 2020 July 15.

British Dental Association. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). 2020. Available at https://www.bda.org/advice/Coronavirus/Pages/facemaskshortage.aspx (accessed December 2021).

Gold J A. Covid-19: adverse mental health outcomes for healthcare workers. BMJ 2020; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m1815.

Godlee F. Protect our healthcare workers. BMJ 2020; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m1324.

Civil Service. Spotting signs of excessive stress and burnout. 2021. Available at https://civilservice.blog.gov.uk/2021/04/06/spotting-signs-of-excessive-stress-and-burnout/ (accessed July 2021).

Strauss, C, Patel-Campbell C. COVID-19 and the female health and care workforce: Survey of health and care staff for the Health and Care Women Leaders Network (August 2020). 2020. Available at https://www.nhsconfed.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/COVID19%20and%20the%20female%20health%20and%20care%20workforce%20report%20August%202020.pdf (accessed December 2021).

36. Hosang G M, Bhui K. Gender discrimination, victimisation and women's mental health. Br J Psychiatry 2018; 213: 682-684.

McAlonan G M, Lee A M, Cheung V et al. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can J Psychiatry 2007; 52: 241-247.

Murphy J, Spikol E, McBride O et al. The psychological wellbeing of frontline workers in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic: First and second wave findings from the COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC) Study. PsyArXiv 2020; DOI: 10.31234/osf.io/dcynw.

Care Quality Commission. 2019 Community mental health survey. 2019. Available at https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20191126_cmh19_statisticalrelease.pdf (accessed September 2021).

Maunder R G, Lancee W J, Balderson K E et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12: 1924-1932.

Mind. The mental health emergency: How has the coronavirus pandemic impacted our mental health? 2020. Available at https://www.mind.org.uk/media-a/5929/the-mental-health-emergency_a4_final.pdf (accessed May 2021).

Arslan H N, Karabekiroglu A, Terzi O, Dundar C. The effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on physicians' psychological resilience levels. Postgrad Med 2021; 133: 223-230.

Nemeth O, Orsos M. Simon F, Gaal P. An Experience of Public Dental Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Reflection and Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 1915.

Mental Health Foundation. Wave 8: Late November 2020. 2020. Available at https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/our-work/research/coronavirus-mental-health-pandemic/key-statistics-wave-8 (accessed May 2021).

Zaheer R, Khan M, Tanveer A, Farooq A, Khurshid Z. Association of Personal Protective Equipment with De Novo Headaches in Frontline Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur J Dent 2020; DOI: 10.1055/s-0040-1721904.

Davey S L, Lee B J, Robbins T, Randeva H, Thake C D. Heat Stress and PPE during COVID-19: Impact on health care workers' performance, safety and well-being in NHS settings. J Hospital Infect 2020; 108: 185-188.

British Dental Association. CDOs commit to roadmap. 2021. Available at https://bda.org/news-centre/latest-news-articles/Pages/CDOs-commit-to-roadmap.aspx (accessed June 2021).

Mental Health Wellness in Dentistry. Mental Health Wellness in Dentistry Framework. 2021. Available at https://mhwd.org/download/mentalhealthwellnessindentistry-framework/ (accessed September 2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the members of the BDA Welsh committees who contributed to this study and report, Dr Roz McMullan, immediate past president of the BDA who championed mental health in her year as president and who inspired the train of work that led to this paper and Dr Vicki Collins and colleagues in the Research Department of the BDA for discussions about this study from inception to publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the survey. Christie Owen and Caroline Seddon drafted the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Owen, C., Seddon, C., Clarke, K. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of dentists in Wales. Br Dent J 232, 44–54 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-021-3756-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-021-3756-7

This article is cited by

-

Powerful tactics to stop overthinking and increase self-assurance

BDJ In Practice (2023)

-

Mental health: Workplace related stress claims signal a profession under pressure

BDJ In Practice (2022)

-

Mental health in dentistry: Has the profession opened up through the years?

BDJ In Practice (2022)

-

Psychological impact on dental students and professionals in a Lima population during COVID-19s wave: a study with predictive models

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Mental health and inclusivity support and education in a UK dental school: a cross-sectional survey

British Dental Journal (2022)