Abstract

The internet and social media give our patients extraordinary access to information; in these unprecedented times of the COVID-19 pandemic, where so much of life takes place online, patients and professionals alike look to the internet more and more for information and (self-)diagnosis. This article details the treatment journey for a patient with a high-grade chondroblastic osteosarcoma of the right maxilla, paranasal area and zygoma, from misdiagnosis through to resection and full rehabilitation with free flap surgery and implant reconstruction. Uniquely, the article details the patient's treatment, in parallel with her own perception of the treatment, as shared on social media.

Key points

-

Alerts the reader to the power of social media as a tool to inform and educate the patient and the dental team.

-

Informs the reader of the power of social media as a means for the patient to describe and share their experiences - both positive and negative.

-

Describes contemporary management of an advanced oral malignancy, from the patient's and the surgeon's perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At the age of 29, Jen Taylor was diagnosed with a high-grade chondroblastic osteosarcoma of the right maxilla, paranasal area and body of zygoma. From referral through diagnosis, resection, reconstruction and dental rehabilitation, Jen posted every aspect of her treatment (Fig. 1), sharing the details in the press and on social media, and acquiring a substantial following of her blog 'The cancer chronicles'.1

The internet and social media give our patients extraordinary access to information and enables the sharing of experiences, both positive and negative. This case report details the complexities of the treatment that she received from her surgical and restorative team, in parallel with the patient's perception of her treatment, as shared by the patient on social media. In these unprecedented times of the COVID-19 pandemic, where so much of life takes place online, patients and professionals alike look to the internet more and more for information and (self-)diagnosis.

Case report

Jen presented to her general dentist with a large swelling of her upper jaw, just under her nose. A provisional diagnosis was made of a dental abscess, associated with a suspected non-vital tooth. She received endodontic treatment and a course of oral antibiotic therapy:

-

'He finished up hollowing out my tooth and taking out the nerve, and tried to cut into my "abscess" to drain it, but with no success. So he prescribed me some antibiotics and referred me and my poor tooth to the root canal specialist. I left in a lot of pain and shock, and £50 poorer. Yes, I got to pay for that lovely treatment'.

Jen was next referred to an endodontist:

-

'He said there was nothing he could do until the swelling went down, so he cut into the "abscess" deeper to try and drain it but once again to no avail. He gave me a temporary filling and said to go home, finish my antibiotics and go back in a couple of days. Another £50 for that privilege'.

When it became apparent that there was no response to the antibiotic therapy, a referral was made to an oral surgeon at Guy's Dental Hospital:

-

'I left with another script for antibiotics, and the instructions to go home and wait for my "urgent referral letter" to reach me in the post'.

Some six weeks later, an incisional biopsy was performed and a diagnosis of a high-grade chondroblastic osteosarcoma of the right maxilla was made:

-

'I met the lovely Dr [...] who whisked me away for scans and managed to get me in for a biopsy on the same day as my appointment. A week later I was back to see him, he was telling me the results and I was relieved and happy to have some idea finally about what was going on'

-

'There's no point in beating around the bush, yesterday a dental specialist told me I have cancer in my jaw. Bone cancer. Sarcoma. I literally have no idea what that is. He apologised a lot and kept asking if I wanted to ask him questions. I didn't know what to ask him'

-

'He seemed very stressed. I reassured him by saying that most people are likely to end up with cancer at some point in their life. He said that's true and assured me we would beat it. I said "of course we will" and asked what's next. He called me stoic. That's nice. I mean…I kind of just want to get rid of it and move on, I've got a lot coming up over the next few months. I don't have time for faffing'.

Following her diagnosis, Jen was referred to the London Head and Neck Sarcoma services based at University College London Hospital (UCLH) for staging and treatment. After staging and multidisciplinary team discussion, she was commenced on neo-adjuvant chemotherapy to reduce the chance of distant spread of the tumour and to reduce the local rate of progression, before surgical resection and free vascularised reconstructive surgery. Her neo-adjuvant chemotherapy2 was comprised of six cycles of cisplatin, doxorubicin and methotrexate over a seven-month period. Her chemotherapy was complicated by acute but temporary kidney injury; hence, methotrexate was stopped after cycle 4:

-

'Chemo is going to be…insane. It will last for 6 cycles, making up 7 months in total [...] Then surgery. The worst part is that the chemo won't shrink that tumour at all, as it is in the bone and not soft tissue. So I will have this lump on my face until they operate next year. But I didn't cry or get mad or upset. I just sighed and nodded and asked when we could start. Yes, I will rock the bald look. And blue wigs'

-

'On good weeks, chemo doesn't have to even factor into your thoughts. Ok so it's pretty much one good week in every 5, but still. That's one week of normality, and that's all it takes!'

During and directly following her neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed to assess tumour response to therapy. Tumour mapping and the planning of the surgical resection margins should be based on pre-chemotherapy radiographic imaging (Fig. 2). Based on the intended surgical resection and the general health condition of the patient, a detailed reconstructive plan, including implant-based dental rehabilitation, is made taking into account both the functional and aesthetic needs of the patient. In Jen's case, the surgical team decided the right scapular area was the most appropriate donor site for a complex combined bone and soft tissue vascularised free flap, a chimeric latissimus dorsi muscle and tip of scapula bone free flap,3 supplied by the thoracodorsal artery and vein. To avoid visible facial scars, the whole combined procedure would be performed via the 'facial degloving' method, which only requires incisions intraorally and inside both nostrils. Surgery was performed a month following cessation of her chemotherapy to allow for systemic recovery:

-

'[...] he [Mr Kalavrezos] cares about how the surgery will affect the patient aesthetically. He places cuts in areas where the patient would usually have lines in order to disguise them as well as possible. He really does care about his patients'.

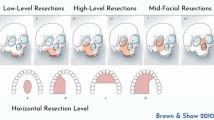

The compartmental resection included the maxilla, from the right pterygoid plates and zygomatic buttress to the contralateral canine region, incorporating the right nasal bone just inferior to the medial canthal area (Fig. 3). As planned, the simultaneous reconstruction of this complex three-dimensional (3D) defect was performed with a chimeric latissimus dorsi muscle and tip of scapula bone vascularised free flap,3 which closed the large defect and provided mid-facial contour.

Some days after the surgery, the flap showed signs of venous congestion, necessitating the harvesting of a leg vein in order to bypass the venous obstruction. This procedure was successful:

-

'I went into surgery at UCLH on the 5th, came out late (16 hr surgery) and started the recovery process. It was gruelling. Then on the Saturday morning, day 6, suddenly the new bit, the "flap" of skin from my shoulder that was making up the roof of my mouth started failing. They hoped it wouldn't be serious and they put me back into emergency surgery, hoping to save it in the 6-hour window they apparently had, planning on a 4-6-hour surgery. So before long they had me under and when I woke up I found out it had been another big 10-hour surgery in which they had taken a blood supply from my leg, to bypass the original blood supply taken from my shoulder, which had failed'.

Histopathological examination of the resection specimen showed complete tumour removal with adequate margins. The baseline post-operative scan three months following surgery showed no tumour recurrence. During those months, the flap was allowed to consolidate. Use of a removable prosthesis through this period would be difficult as a result of the ever-changing remodelling tissues and the lack of firm support or retention. Dental rehabilitation with an osseointegrated implant-supported prosthesis was seen as the best way forward:

-

'After weeks (months overall!!! 7 in fact!) of waiting and chasing (and healing!) I finally got the call I had been waiting for: a referral to the seemingly elusive teeth man'.

Although the free flap reconstruction elegantly closed the large defect, sealing the mouth from the nose, and provided much-needed bulk to the midface, the particular configuration of the bone flap and pedicle meant that the scapula could not be oriented to anchor dental implants, and so alternative sites needed to be used. In this complex reconstructed anatomical environment, implant planning took place using a combination of virtual modelling in implant planning software and physical modelling using a 3D printed model4 of the reconstructed maxilla. To establish an approximate relationship between the implants and the future prosthesis, a wax tooth setup was designed and subsequently copied to make a resin template:

-

'First they will look at making a denture and see how it fits (if it even fits after everything that has changed in there) and then later consider implants. Until we start trying, we don't know if it will work. If it doesn't work, it'll be back to my surgical team and back into surgery to look into more reconstruction from another body part [...]'.

The exceptionally large resection and the resulting scarring and tethering made access for treatment and definition of the restorative space particularly challenging:

-

'Also there's a good chance my lip won't be able to fit over teeth anymore, especially with my sunken face, collapsed nose and the scar tissue from the stitches. So there might be issues there with actually fitting teeth in my mouth. And even if I can get the teeth in, they won't fix these things so I'll always look a bit odd'.

With the addition of fiducial markers, the resin template was used as a radiographic stent.5 Several hours were spent working with implant planning software (DTX Studio Implant), comprehensively investigating different approaches to treatment with zygomatic and/or standard dental implants. The 3D visualisation enabled a detailed pre-visualisation of each potential plan before surgery - finally deciding upon a plan in which three zygomatic implants were used (Fig. 4a). The tooth setup allowed screw access to be planned and the relationship of the prosthetic teeth to the implant platforms to be understood. Eventually, an implant drill guide was 3D printed using a stereolithographic process. The cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) dataset was also 3D printed in nylon, using selective laser sintering to produce an autoclavable model for further visualisation and tangible guidance at the time of surgery (Fig. 4b). Surgical access to place the implants was carefully considered, along with the need to bodily support the lip at a high level. Implant surgery took place 13 months after the surgery, under general anaesthesia, with oral intubation further compromising access:

-

'I was so looking forward to my surgery to get my implants. I knew I had to manage expectations. People would say "don't worry, you'll look fine, they'll make you look just how you used to", completely dismissing how difficult this job was and not wanting to acknowledge that there are no guarantees. But I had to, I had to manage both my expectations and everyone else's'.

Surgical access for placement of zygomatic implants was difficult; due consideration was given to an external approach, using the reverse zygomatic implant.6 The limited bone bulk present on the right side presented a particular challenge. Implants were placed into the right infraorbital rim, the right residual zygoma and the left zygoma, traversing the dentate alveolus:

-

'Waking up from the implant surgery, my face was puffy, but it was obvious already how much a difference it had made. I didn't have teeth yet, but the implants were specifically placed forward to fill my face out, and my lip was released and re-set. I had a face again' Post-op: 'Weirdly, the pain in my face has been greater than it was from THE surgery'.

Two days post-implant placement, impressions were taken. A further five days later, a total of one week following implant placement, a screw-retained resin temporary bridge was provided:

-

'They're not yet perfect, but it took me mere minutes to realise how much of a difference they made. Ordering coffee after I got them in, I smiled, and I felt normal. I didn't feel like I was behind a barrier of "cancer face". I could speak clearer, and there was less chance of spitting on people now I had my teeth back and my lip moved. I haven't yet found the words to express this total change in my persona from not having teeth and having a weird sunken face, to having my face filled out and having teeth. But in that moment, I got my personality back, I got my confidence back, and I got my life back. Well, nearly. Ask me again in 3 months when I get my proper teeth. That will be the last step, so I can munch to my heart's content, and I'm hopeful they'll fit slightly better'.

Healing took place over subsequent months, at which point impressions and registrations were made. At UCLH, oncology patients with extensive defects will typically receive fixed, resin-veneered titanium implant prostheses or removable implant-supported overdentures to restore function. In this case, the extensive resection shortened the lip and the large osseocutaneous flap limited the restorative space. A porcelain bonded to milled cobalt chrome fixed bridge was provided to rigidly link the implants and provide a robust and aesthetic reconstruction in the limited restorative space (Fig. 5a).

Supporting the lip without creating the appearance of a 'snarl' and managing speech while also achieving a pleasing dental relationship can be a particular challenge. Returning a patient to their original pre-surgical state after such extensive treatment is seldom a realistic proposition; it is important not to promise too much:

-

'The lab people are great, they really listen and understand. But it was also a bit stressful, because there are things I don't like that they may have done for certain other reasons and they said they'd change it if I want and it's up to me to decide…but I don't know if changing the things I want will make something else worse…So I was a little scared that I'd get the things I want and be less happy with how it turns out overall. I can only use common sense and the knowledge of how I want them to look, I obviously don't know the intricacies of creating teeth'.

Discussion

Jen writes about her initial diagnosis, she details the various stages of her chemotherapy, tabooed side effects, and the people whom she has met along the way including the clinicians and other patients. She writes about adapting to daily activities and her pre- and post-operative experiences, all the while writing in the present rather than past tense, so her words have been written without yet knowing a definitive outcome.

The internet and social media gives our patients unprecedented access to information, though it is not always of adequate quality and readability,7 and enables the sharing of their experiences. Writing about their experience may be cathartic8 or rewarding,9 and this may benefit other patients who have experienced, are experiencing or are to experience similar treatment, especially for a rare diagnosis, facilitating shared decision-making. On the other hand, information may be difficult to understand,10 misinformation may be alarming and misunderstanding what is shown may deter patients from seeking treatment, or motivate them to seek inappropriate treatment. There may also be a real risk of clinicians resorting to defensive practice based on the intricacies of patient perceptions and what may be portrayed in social media.

Never before has the dental profession experienced this sort of 'exposure'. Access to social media means that we are on view to the public at large; both positive and negative experiences will be reported and discussed - perhaps negative experiences are more likely to be reported. This information is easily accessible to the local community, the press and the legal profession. The impact of COVID-19 and the global pandemic and lockdown will no doubt accentuate online interaction. Consider this:

-

'I suppose you can't expect an everyday dentist to know how to spot a very rare cancer in a very rare location. I suppose he did everything he could, everything within his realm of expertise. You just wouldn't expect them to do work if they're not sure what the problem is. I don't know if there's anyone to blame. It's just a series of unfortunate events, culminating in a cancer diagnosis'.

Engaging with social media may provide a wonderful opportunity for the dental team to better understand what their patients endure and to learn from their experience - and to learn how to be more sensitive too. It was through Jen's blog that this conversation was brought to light, initiating team training at the practice:

-

'The receptionist who booked me in was lovely but I had to laugh. She asked me if I'd had an accident and I said no, cancer, and they cut my jaw out and now I'm just waiting for teeth. "Oh so your mum or dad has it too?" She asked. The old what-did-you-do-to-cause-it-so-I-can-check-I-won't-get-it job. Sorry love, you're just as likely to get cancer as I was. Most cancers don't have a genetic, environmental or lifestyle cause, we didn't do anything wrong to bring it on ourselves…'

Social media raises awareness. The public perception of dentistry in the UK perhaps undervalues the contribution of the dental team to the nation's health and underestimates our scope of practice, and so there is also an opportunity for the profession to benefit from favourable exposure. On the other hand, the team faces the new challenge of working under the constant scrutiny of the 'public eye' with raised expectations and pressure for the dental team to adapt and deliver accordingly.

Head and neck cancer is the eighth most common cancer in the UK, accounting for 3% of all new cancer cases.11 However, although there has been a recent rise in head and neck cancer as a result of an increase in human papillomavirus-associated cancer, sarcomas are a distinctly different group of malignant neoplasms of mesenchymal origin and comprise less than 1% of all cancers. Of all adult sarcomas, only 10% occur in the head and neck region, with five-year survival rates ranging from 27% to 84% in various studies.12 Chondroblastic osteosarcoma is a rare tumour and is a subtype of osteosarcoma with a prevalence of 11% to 50%.13 Early diagnosis remains a challenge because of insidious clinical presentation. Symptoms such as an enlarging mass with or without the presence of pain, loose teeth, cranial nerve dysfunction, unilateral sinusitis, nodular vascular lesions, epistaxis, unilateral nasal mass, hoarseness, dysphagia and/or odynophagia should raise suspicion of a sarcoma and trigger an urgent referral to a sarcoma centre. Bone pain at night should always be considered a red flag. Diagnostic imaging such as ultrasound, MRI, CT and PET are employed in the head and neck instead of plain radiographs. Excisional biopsies must be avoided at all costs to prevent contamination of the field, which would jeopardise treatment and outcomes.14

Oral cancer is typically managed with surgery or with radiotherapy, alone or in combination - sometimes with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Fortunately, Jen did not need radiotherapy; radiotherapy substantially complicates implant treatments when high doses are delivered to implant sites and it is rarely given for osteosarcomas. The successful use of a removable prosthesis in a patient who has been reconstructed with a free flap is often complicated by the presence of thick 'bouncy' and tethered tissues, lack of a defined ridge/sulcus, reduced restorative space, difficult access and a sensory deficit which reduces proprioceptive feedback - very much the situation that presented in this case. On the other hand, a removable prosthesis may permit more control over appearance. In Jen's case, the implants were placed in native bone, which might have been more easily accomplished at the time of free flap surgery (primary insertion) and this could possibly have provided a more rapid rehabilitation15 - though this was impractical at the time, given the overall extent and complexity of the reconstructive surgery:

-

'You come out the other side of this ridiculously big surgery and your face isn't what it used to be. And people tell you [sic] should just be grateful because you're alive. And you are grateful that you're alive. Very. But you see yourself in the mirror every day and you see this strange face where yours once was, and you brush your teeth, or what's left of them, and you see the gap where they used to be. Every morning when you look in the mirror you are reminded of what happened, of yet another thing that cancer has taken away from you. So you stop looking in the mirror so much, a quick check of your face before you go to work. You even cut that down. You might catch your reflection in something and you're reminded again, and it all comes flooding back. You get a few moments of forgetting, forgetting what happened and feeling normal, and then you're reminded as soon as you see yourself again. So you avoid mirrors entirely and you think "this is fine", and you tell yourself "I don't look that bad, people probably can't even tell, it's just me"'.

As we become more specialised, perhaps seeing multiple similar cases, all with significant problems, there is a danger that we may forget that what may appear perfectly quotidian to us is an exceptionally significant, life-changing event to the patient:

-

'The work that they are doing is beyond belief, and I have gone into my surgeries with complete trust in these people, putting my life in their hands. From the beginning, the surgeons and my implant specialists prepared me for that fact that although we were hoping for everything to go wonderfully smoothly, it really is a big and difficult job, and there are no guarantees. I just want to stress this fact. There were so many things that could not go according to plan. Apart from the usual surgery things, there's also the fact that they're trying to fix implants into a "jaw" that is actually a shoulder bone…Like…what?! How is that even possible?'

Yet, in the spirit of Montgomery,16 we also see how important it is to answer the patient's questions, even if they haven't necessarily been asked:

-

'[...] I appear to not be told a lot of things. Maybe that's normal, but I seem to be expected to know what to ask and who to ask it to in order to find anything out'.

Jen's insights and her postings on social media give us a unique perspective on the need for careful and thoughtful communication, with a focus on patient-centred care. We read what information she has taken on board and she also portrays the manner in which something has been said. It is also perhaps showing that, even in such extreme surgery, it is entirely acceptable to be factual with the patient.

Jen is not alone; she has openly posted her treatment, rather than withdrawing from society as may be the case for some patients who have experienced radical surgery. She has filled in the 'gaps' between every stage of the extensive multidisciplinary care she received. This close documentation raises not only awareness of a patient's experience but the imperativeness of rehabilitation in its entirety.

Most importantly, Jen makes a case for post-operative reconstruction with dental implants; the authors concur with the Royal College of Surgeons guidance17 that, where practical, this should be the norm for any patient going through such procedures:

-

'My surgeons, oncologists, nurses saved my life, [the implant team] gave it back to me. Or as my friend put it, my oncologists and surgeons added days to my life, but [the implant team] added life to my days' (Fig. 5b).

References

Jen Eve. The Cancer Chronicles. Available at https://thecancerchronicles.blog/ (accessed November 2020).

Gerrand C, Athanasou N, Brennan B et al. UK Guidelines for the management of bone sarcomas. Clin Sarcoma Res 2016; DOI: 10.1186/s13569-016-0047-1.

Piazza C, Paderno A, Del Bon F et al. Palato-maxillary reconstruction by the angular branch-based tip of scapula free flap. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017; 274: 939-945.

Dawood A, Marti B M, Sauret-Jackson V, Darwood A. 3D printing in dentistry. Br Dent J 2015; 219: 521-529.

Dawood A, Patel S, Brown J. Cone Beam CT in Dental Practice. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 23-28.

Dawood A, Collier J, Darwood A, Tanner S. The reverse zygomatic implant: a new implant for maxillofacial reconstruction. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2015; 30: 1405-1408.

Riordain R N, Hodgson T. Content and quality of website information on the treatment of oral ulcers. Br Dent J 2014; 217: E15.

Merolli M, Gray K, Martin-Sanchez F. Therapeutic affordances of social media: emergent themes from a global online survey of people with chronic pain. J Med Internet Res 2014; DOI: 10.2196/jmir.3494.

Sherman L E, Hernandez L M, Greenfield P M, Dapretto M. What the brain 'Likes': neural correlates of providing feedback on social media. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2018; 13: 699-707.

Leung J-Y, Riordain R N, Porter S. Readability and quality of online information regarding dental treatment for patients with ischaemic heart disease. Br Dent J 2020; 228: 609-614.

Cancer Research UK. Head and neck cancers statistics. Available at https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/head-and-neck-cancers#heading-Zero (accessed November 2020).

Vassiliou L-V, Lalabekyan B, Jay A et al. Head and neck sarcomas: A single institute series. Oral Oncol 2017; 65: 16-22.

Sun H-H, Chen X-Y, Cui J-Q, Zhou Z-M, Guo K-J. Prognostic factors to survival of patients with chondroblastic osteosarcoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012636.

Kalavrezos N, Sinha D. Head and neck sarcomas in adulthood: current trends and evolving management concepts. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020; 58: 890-897.

Hutchison I L, Dawood A, Tanner S. Immediate implant supported bridgework simultaneous with reconstruction for a patient with mandibular osteosarcoma. Br Dent J 2009; 206: 143-146.

Main B G, Adair S R L. The changing face of informed consent. Br Dent J 2015; 219: 325-327.

Dabar U, Shahdad S, Ashley M et al. Guidance on the standards of care for NHS-funded dental implant treatment. 2019. Available online at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/dental-faculties/fds/publications-guidelines/clinical-guidelines/ (accessed November 2020).

Acknowledgements

Andrew and Hannah are joint first authors.

This article is a product of an experienced multidisciplinary team, each member bringing their own particular skillset to the table, working individually at times: Mr Nicholas Kalavrezos, Consultant in Head and Neck Surgery; Ms Deepti Sinha, Specialist in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Senior Fellow in Head and Neck Sarcoma Surgery; Dr Andrew Dawood, Honorary Consultant in Implant Dentistry, who carried out the implant treatment; and Ms Hannah Fullerton, lead surgical implant nurse, who carried out the digital planning and collated Jen's posts on Instagram and her blog, including Figures 1, 4b and 5b. Not least, the authors acknowledge the exceptional contribution of Ms Jen Taylor - the patient from whom we have all learnt so much. Post-lockdown 2020, at review, Jen presented with a recurrence. You can follow her progress on social media platforms.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fullerton, H., Dawood, A., Kalavrezos, N. et al. Contemporary management of advanced midface malignancy in the age of Instagram - a parallel surgical and patient's perspective. Br Dent J 231, 233–238 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-021-3320-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-021-3320-5