Abstract

Introduction Dentists are known to function under stressful conditions. It is important to monitor, examine and understand the psychological effects the unprecedented challenge of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has had.

Aims To compare levels of psychological distress in UK dentists, before and during the pandemic, to determine if this was affected.

Materials and methods An online survey collected demographic data, levels of psychological distress (GP-CORE) and experiences from UK dentists during the 'national lockdown' period of the pandemic. Statistical and thematic analyses were performed and data compared with previous research.

Results Psychological distress was lower in UK dentists during the national lockdown period when compared to previous research using the same measure. GDPs, those in England and those with mixed commitment reported the highest levels of psychological distress. Most dentists had been affected by the pandemic. Some who were remotely working during this time valued the time away from the profession, relishing the absence of regulatory and contractual stressors, and used lockdown as an opportunity to re-evaluate their lives and careers. Others found the conditions stressful with some previously acknowledged stressors remaining and novel stressors introduced.

Conclusions We argue that the altered balance of stressors and the resulting reduced psychological distress is further evidence of the need for reform of the profession to improve working lives. Given the importance of mental health and wellbeing, it is vital that monitoring continues.

Key points

-

Identifies stressors for dentists and their perceived impact, including novel stressors introduced during the lockdown period.

-

Outlines the variety of circumstances and working environments dentists were working in during lockdown.

-

Shows that overall psychological distress was reduced during lockdown for dentists, attributed to the stressors of day-to-day clinical dentistry being alleviated for many.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, a β-coronavirus (CoV), was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation in March 2020.1 CoVs, which commonly infect mammals,2,3,4 are RNA viruses suggested to have pandemic potential due, in part, to their large genome and mutation rate.5 The dominant mode of person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is from the respiratory tract via droplets or indirectly via fomites and aerosols,1,6 with the latter being of heightened importance in clinical dentistry due to the unique nature of dental interventions.7,8 SARS-CoV-2 is not the first CoV to cause a pandemic but is an epidemiological challenge as asymptomatic carriers can transmit the virus, which can be fatal,9 during their incubation periods10 and most infections are mild or asymptomatic.9

Significant outbreaks of disease are one of the greatest risks faced by society, with pandemics impacting health and disrupting public services and economies.11 The scale of this pandemic is unprecedented in recent history and the UK government announced measures in response.11 Funding was made available to support health and social care and businesses, though some (including self-employed dentists earning anything above £50,000) were excluded,12 and control measures were initiated with laws passed to prevent non-essential travel and socialising, resulting in shutdown of public life and, for many, enforced isolation.11,13 This affected wellbeing in adults, with the population suffering from high levels of psychological distress and the nation as a whole just under the threshold for psychiatric morbidity.14 Psychological distress was particularly high for women, ethnic minority groups and key workers, with the latter primarily concerned about their health and safety, specifically the difficulty in following social distancing advice and limited or no protective clothing available.14,15

Dentists are believed to have high potential exposure to SARS-CoV-2, second only to medical practitioners due to the level at which they work with others and the exposure to disease, both measured by using a scale for proximity and frequency, respectively.16,17 In light of this, on 25 March, all routine dental care was effectively ceased in the UK and, during this time, most dental practices were closed and offered a remote triage and advice service, referring to urgent dental care centres for face-to-face treatment as appropriate. However, there were regional differences in the devolved nations. Many dentists also volunteered to be redeployed, including community dentists to staff urgent dental care centres and hospital dentists to work in other areas of secondary care, including treating COVID-positive patients in intensive care.

The impact that previous pandemics (such as SARS, MERS and flu) have had on healthcare workers (HCWs) has been widely reported. A systematic review found that working on the frontline in direct contact with infectious patients, being quarantined, a greater workload, a lack of perceived safety and greater risk of exposure were all contributing factors to reduced mental health in HCWs.18 Lai et al.19 reported on the mental health of HCWs in China during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the majority of whom (60.8%) were nurses and worked in Wuhan (60.5%), the origin of the current pandemic. The results showed that 50.4% had symptoms of depression, 44.6% anxiety, 34.0% insomnia and 71.5% distress (post-traumatic stress). Those who were nurses, who worked on the frontline and who worked in Wuhan exhibited higher scores. This has been attributed to increased workload and the close patient contact nurses had with COVID-19 patients, plus the increased risk of exposure and perceived danger. At the time this study was conducted, concerns surrounding personal protective equipment (PPE) have been widely reported, including by dentists.20 It has been argued that this constitutes a form of institutional betrayal, whereby powerful institutions act in a manner that harms those that rely on them for safety, which can exacerbate psychological distress.21

Previous research has highlighted that dentistry is a stressful profession, with fears surrounding litigation and issues relating to regulation cited as key stressors for dentists in the UK.22 Dentists also reported high levels of occupational stress (55%), burnout (86%) and psychological distress (68%). To cope with the pressures of practising, dentists have reported using a variety of different coping strategies, including active planning, forgetting about work, resting, and indulging in sports and hobbies.23,24

There have been a few studies looking at the effect of the current pandemic on dentists. A study conducted in Italy found that 85.1% were concerned about contracting COVID-19 during their clinical activities and this fear was strongly associated with elevated psychological distress.25 However, although concerns over the virus were high, the self-reported anxiety level of dentists as measured by the GAD-7 measure was mild. Dentists were deeply concerned about the future of the profession, especially concerning the financial viability of dental practice going forward. These sentiments have been echoed in recent BDA work.12 Similarly, recent work looking at psychological distress in dentists and dental hygienists in Israel found 11.5% to show elevated psychological distress, which was associated with fear of catching the virus, underlying medical conditions and greater subjective overload (job stress).26

Aims

The current study will therefore look at the levels of psychological distress in UK dentists during a period of 'lockdown' and uncertainty for the profession. Direct comparisons can also be made to previous research,22 to determine whether UK dentists are experiencing greater psychological distress than they were before the pandemic.

Methods

All dentists in the UK were invited to answer an electronic questionnaire to gather opinions on how the profession should resume routine care post-SARS-CoV-2. Questions covered demographics, the General Population-Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (GP-CORE) as a measure of psychological distress (described below),27 and the opportunity to comment on how the pandemic had affected them and how they thought it would affect practice in the medium and long term. The survey was launched on 22 May and was in the field for six days. An incentive - entry into a £100 John Lewis e-gift card prize draw - was offered.

GP-CORE

The GP-CORE is a 14-item measure to assess psychological distress in a non-clinical population. Respondents rate how frequently they have felt a certain way in the last week on a Likert-type scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (most or all of the time). Items include: 'I have felt able to cope when things go wrong' and 'I have difficulty going to sleep or staying asleep'. Lower scores indicate greater wellbeing. The measure has been shown to demonstrate good reliability and validity.27 Cronbach's alpha was shown to be 0.90.

Data analysis

Anonymised data were collated and analysed using SPSS (version 24, IBM, New York, USA). Both descriptive and inferential statistics are reported, in the form of percentages, t-tests and ANOVAs. Where post-hoc tests have been used, a Bonferroni adjustment was applied to take into account multiple comparisons. A p value of <0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant; where graphs are provided, the error bars represent 95% confidence intervals around the mean. Qualitative data were thematically analysed.

Respondents who did not consent or who were based overseas, retired, full-time students or dental care professionals were removed, as were partial responders. Responses for each region were similar; therefore, data are presented for the UK as a whole.

Results

Usable responses were obtained from 5,170 individuals (please see Table 1 for demographic information). This accounts for approximately 12% of all UK dentists registered on the General Dental Council (GDC) register. The majority (90.2%, n = 4,384) were general dental practitioners (GDPs), with 50.6% (n = 2,204) associates and 47.4% (n = 2,065) practice owners. National Health Service/Health Service (NHS/HS) commitment for GDP respondents varied, with 42.4% (n = 1,858) of dentists providing <25% NHS/HS treatment (21.7% of which were exclusively private) and 36.9% (n = 1,614) providing ≥75%. Over half of respondents (57.7%, n = 2,946) were White British, with the majority of all respondents (85.7%, n = 4,437) conducting most of their work in England.

Psychological distress

Prior to calculating mean scores and prevalence rates, reverse scoring and thresholds were administered according to guidelines.27 Overall 57.8% exceeded the clinical threshold for psychological distress. This is lower than levels reported in previous research conducted on UK dentists before the pandemic in 2017, which was 67.7%.22

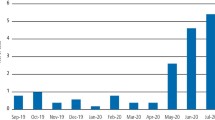

There was a significant difference between mean levels of psychological distress between different fields of practice - F(4, 4,856) = 10.98, p <0.001. GDPs reported significantly higher levels than hospital dentists (p <0.001) and those working in another field of practice (p = 0.02). Community dentists also scored significantly higher than hospital dentists (p = 0.001).

Dentists in most fields of practice were shown to have lower levels of psychological distress than in 2017 (pre-pandemic) (see Figure 1). This was significantly lower for GDPs, community dentists and hospital dentists.

Although dentists practising in England exhibited the highest levels of psychological distress (M = 1.83, SD = 0.79), there were no significant differences between the nations - F(3, 5,176) = 2.03, p = 0.11.

For GDPs, practice owners reported significantly higher levels of psychological distress (M = 1.83, SD = 0.79) than associates (M = 1.67, SD = 0.75) - t(4,267) = 6.79, p <0.001.

Psychological distress was also shown to significantly differ by NHS/HS commitment level - F(1,097.70) = 2.52, p = 0.03. Post-hoc tests revealed that those with 25-49% NHS level reported significantly higher levels of psychological distress than those with 75-99%, 1-24% and 0% NHS/HS commitment levels (exclusively private).

Compared to levels in 2017 (pre-pandemic), those with higher NHS/HS commitment levels (50% and above) scored significantly lower for psychological distress. Those with 25-49% NHS/HS level exhibited higher scores for psychological distress than pre-pandemic; however, this was not significant. Those with less than 50% NHS/HS commitment levels did not significantly differ from their pre-pandemic scores. These differences are presented in Figure 2.

How affected by pandemic

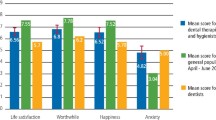

Ninety-three percent of participants stated that they had been affected by the pandemic; 77.2% of respondents stated that they had been impacted financially and 41.1% stated that their mental health had suffered.

There were differences between practice owners and associates, with a higher percentage of practice owners reporting negative consequences from the pandemic. Please see Figure 3.

Qualitative findings

When dentists were asked about the pandemic and the impact it has had on them, the results were varied, reflecting the different roles and working circumstances of dentists during this period. However, there were some common themes that emerged. For dentists who were working remotely, some respondents reported finding the time away from face-to-face clinical dentistry to be a positive and welcome experience (Table 2). Some had been finding their jobs overwhelming and the time off was allowing mental recharge and a physical break. For some, this was the first break from practice in decades. The pandemic and its immediate effects had been accepted, with some of those who responded not previously being able to fully acknowledge how destructive to health and wellbeing their work and its stresses were.

The lack of pressure from the NHS, patients, GDC, Care Quality Commission and GDPR was noted by many as being positive, with some dentists stating that they had never felt better than they did during this period. Some respondents valued, or were enjoying, the time spent with their family and the ability to partake in hobbies such as gardening, taking exercise, sleeping and enjoying the good weather, while some were expanding their professional knowledge or reflecting on and evaluating careers. This highlighted disillusionment; some respondents were concerned over restarting the treadmill and others wished to cut down their working hours.

Some who responded to the questionnaire acknowledged that, while they were enjoying the time away, others may have struggled. Some employed dentists, who were still seeing patients face-to-face, reported that they welcomed the opportunity to continue providing a service for patients and, as a healthcare professional, would find it hard not to do so. The level of pressure exerted onto practitioners at this time was noted and, on a practical level, was affecting professional and personal aspects such as concentration and sleep. Stressors named at this time were mainly financial, and included factors such as the threat of clawback and pressures such as bankruptcy or selling assets such as the family home to stay afloat. Dentists were also deeply concerned about their patients and the impact the pandemic will have on them, and the anticipated backlog of treatment (Table 3). Other stressors - such as the increased time at home affecting family relations, home schooling being difficult to balance with professional responsibilities, concern of the new norm, and health and wellbeing concerns for families, staff and patients - were also cited.

It was evident that some respondents felt let down by those leading the profession (Table 4), who were seen to be 'passing the buck', and the lack of trust and value that they were shown, believing the pandemic had exposed how poorly the profession is run, particularly in England. The profession was seen as being 'in a complete mess' and private dentistry aggrieved. There was anger and a sense of betrayal felt by dentists both for patients being left to fend for themselves and for them as practitioners, with respondents feeling bewildered, embarrassed and powerless at/with the situation.

Practitioners provided insight into how they believed the pandemic would affect practice. Few believed there would be little consequence, with the majority predicting a difficult future for the profession. Suggested effects fell into five themes (Table 2). The interruption to practice was suggested as being a push factor for early retirement, cutting hours worked and possibly leading to less dentistry being performed across the UK. The possibility that reform might follow was raised and could be welcome.

Discussion

Overall, nearly half of dentists reported that the pandemic had affected their mental health, with a high proportion (77%) stating that it had impacted them financially. It is apparent that the pandemic has caused upheaval to dentists' working lives and has brought with it many challenges for the profession.

The finding that dentists reported lower levels of psychological distress during the current pandemic and period of lockdown was unexpected. Research focusing on HCWs has typically found higher levels of mental distress during a pandemic; however, there are exceptions. For example, previous research found that HCWs working on the frontline during a H1N1 pandemic reported comparable levels of psychological distress to scores in HCWs before the pandemic.28 Other research has evidenced that HCWs did not differ from control subjects for psychological distress during a SARS outbreak.29 Greater confidence in infection control, education and understanding about viruses, and a sense of purpose and community (we are all in it together), may act as protective factors for HCWs in these circumstances. A recent study in the UK showed that key workers expressed higher levels of life satisfaction during the current pandemic, which was attributed to feeling that their work is important and feeling appreciated.14 This could possibly explain why hospital dentists and community dentists reported lower levels of psychological distress during the lockdown period, as they were more likely to be performing urgent clinical dentistry or redeployed to the frontline.

Another factor that needs to be considered is that much of this research has focused on HCWs who are working on the frontline treating infected patients. At the period this research was conducted, dentists in the UK were mainly working remotely, particularly GDPs. In day-to-day dentistry, practitioners face, for example, a high regulatory burden and litigation fears,22 which were (for some) alleviated during the period of reduced activity, as reflected in qualitative data. Additionally, time spent on coping strategies, including hobbies, was increased. For some, the pandemic and lockdown period has provided distance from work and time to evaluate and reflect on interests, beliefs and values, and an opportunity to find meaning in life and take control.30 Given that living in a way that fulfils our passions can protect against mental illness,31 and pastimes such as residential retreats have been suggested to benefit mental health,32 it may not be surprising that time away from known stressors reduced psychological distress in dentists. While the enforced break from clinical work could be welcome or beneficial for practitioners, reflection by some is aiding the realisation that the profession can be a thankless and stressful one, and the triggered re-evaluation of their careers has accumulated in plans to exit the profession. The realisation that dentistry is not enjoyable and the wish to step away from the profession is not a welcome one, and is further evidence that improvements to dentists' working lives is needed.

Despite the decrease in psychological distress during this pandemic, the level of psychological distress in dentists remains high in comparison to other professions.33,34 While some stressors were reduced or eliminated, others were heightened and new stressors introduced. Concerns relating to the financial viability of roles, practices and the profession were prominent, as were concerns for PPE. The latter raises the issue of institutional betrayal - institutions acting, deliberately or by omission, in ways that harm those dependent on them for safety and wellbeing,35,36 with inadequate PPE being suggested to adversely affect mental health in addition to risking infection.21,37 PPE concerns were not unique to dentistry.38 Reports of NHS doctors warned not to go public about PPE shortages were published39 and concerns expressed over guidance recommending PPE reuse,40 with similar situations occurring overseas.41 Feelings of betrayal were compounded by lost trust in leaders of the profession and the lack of communication during the pandemic. The opinion that dental services are the 'Cinderella service' were reinforced, with dentists feeling scepticism, being passed over and let down by the government. Given the prohibition of many aspects of routine patient care during the pandemic, it may not be surprising that some dentists have found this period stressful. Anxiety and self-reported stress are common reactions to this pandemic42 - considering known stressors for dentists include dissatisfied patients and that many dental practitioners enjoy their jobs/treating their patients and derive satisfaction from alleviating suffering, being prevented from treating their patients could have impacted negatively on them.22,43 Additionally, novel financial and business concerns stemming from the pandemic have caused anxiety.

Our findings also found that, for dentists working in general practice, practice owners reported significantly greater psychological distress (64.8%) compared to associates (55.3%). This is not surprising given that practice owners have the financial burden of trying to maintain their business. Indeed, many respondents commented on the financial side of running a practice and the worry and stress that has been caused by SARS-CoV-2. For NHS practices, contract funding has been maintained, but for mixed practices and solely private practices, revenue has been significantly reduced. This may explain the finding that those with less than 50% NHS commitment (including purely private) showed similar levels of distress pre-pandemic, yet those who had 50% or more NHS commitment level had significantly lower scores of psychological distress during the pandemic, as essentially, those with a higher NHS commitment are still being paid a higher proportion of their income, alleviating some financial pressure.

It is evident that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has affected dentists in a variety of different ways and this has implications for the profession as a whole. Although dentists experienced a reduction in psychological distress during lockdown compared to pre-pandemic levels, that is not to say that mental health has not been adversely affected. The current study employed a sole measure for examining mental health in the sample, which may not be able to capture the whole picture. Measures looking at different facets of mental health (for example, stress, post-traumatic stress, burnout and coping) may have yielded more nuanced results and provided a greater understanding into how UK dentists' mental health has been affected. Additionally, previous research has found that there may be delayed effects of stress, with some displaying 'denial' or running on 'auto-pilot' while in the midst of an infectious disease pandemic.44,45 Once the threat of a pandemic has passed, this chronic stress has been shown to manifest in post-traumatic stress symptoms, burnout and increased psychological distress.44,45,46 This may be particularly true for dentists who were redeployed to the frontline, working in challenging conditions very different to their usual environment of clinical dentistry, in which they may have witnessed distressing incidents such as patients dying. For many dentists, it may be that they are most at risk after routine dental care has resumed or the pandemic is over. It is likely that all dentists will have to adopt a new way of working, with challenges such as reduced patient numbers and increased costs to navigate. It would therefore be prudent to monitor the mental health of dentists during and after the current pandemic, to ascertain if there are any sustained effects. A more comprehensive programme of research looking at various facets of mental health would also be beneficial.

Limitations

There were some limitations to our study that need to be considered. As it was a cross-sectional study, there are inherent limitations with this methodology. Firstly, causality cannot be determined. Additionally, when we are making comparisons to pre-pandemic levels, we are not comparing the same cohort of dentists, so there could be potential differences between the cohorts. Further research could utilise a longitudinal approach to allow more insight into the causal processes involved.

A further limitation is that of representativeness and generalisability. Over 90% of those who responded were GDPs, which (although the largest field of practice) is likely an over-representation, as previous BDA research has typically yielded figures closer to 75-80%.22 A large proportion of GDPs who responded to this survey were practice owners (47.4%), when in the population, it is much lower - for example, for those performing any level of NHS dentistry in England, practice owners make up 20% of the population, with 80% being associates.47 When compared to the GDC register,48 our sample was broadly representative for gender (50.5% female compared to 50.4%) and region of the UK (85.7% England, 4.3% Northern Ireland, 6.3% Scotland and 3.8% Wales, compared to 82.0% England, 4.0% Northern Ireland, 9.9% Scotland and 4.1% Wales). However, our sample had an older age profile than registrants (34.2% of our sample was under 40, compared to 49.1% of those on the register who were 40 or under). It is important to note that the GDC register includes all registered dentists, regardless of whether they are currently practising.

Despite this, this work provides a valid and novel insight into how dentists have been affected by the pandemic.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates that, despite dentists' levels of psychological distress being reduced (presumably as the vast majority of respondents were no longer exposed to the 'normal' day-to-day stressors), novel stressors surrounding financial viability, PPE, dental leadership and changes to the dental profession going forward were introduced. It is therefore vital that research is conducted to monitor the ongoing and sustained effects this pandemic has on dentists' mental wellbeing, especially when the day-to-day stressors of performing routine care are reintroduced. The pandemic has further highlighted aspects of the profession that work to the detriment of practitioners and may offer a unique opportunity for meaningful reform in the profession, to benefit not only dentists but also dental teams and patients.

References

Contini C, Di Nuzzo M, Barp N et al. The novel zoonotic COVID-19 pandemic: An expected global health concern. J Infect Dev Ctries 2020; 14: 254-264.

Hageman J R. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19). Paediatr Ann 2020; DOI: 10.3928/19382359-20200219-01.

Chen Y, Liu Q, Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: Genome structure, replication and pathogenesis. J Med Virol 2020; 92: 418-423.

Li G, Fan Y, Lai Y et al. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J Med Virol 2020; 92: 424-432.

Kock, R A, Karesh W B, Veas F et al. 2019 n-Cov in context: lessons learned? Lancet Planet Health 2020; DOI: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30035-8.

Mackenzi J S, Smith D W. COVID-19: a novel zoonotic disease caused by a coronavirus from China: what we know and what we don't. Microbiol Aust 2020; 41: 45-50.

Checchi V, Bellini P, Bencivenni D, Consolo U. COVID-19 dentistry-related aspects: a literature overview. Int Dent J 2020; DOI: 10.1111/idj.12601.

Ather A, Patel B, Ruparel N B, Diogenes A, Hargreaves K M. Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19): Implications for clinical dental care. J Endod 2020; 46: 584-595.

Singhal T. A review of Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19). Indian J Paediatr 2020; 87: 281-286.

Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 970-971.

National Audit Office. Overview of the UK government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. Available at https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Overview-of-the-UK-governments-response-to-the-COVID-19-pandemic.pdf (accessed May 2020).

British Dental Association. Practices weeks from collapse without rapid action from government. 2020. Available at https://www.bda.org/news-centre/press-releases/Pages/Practices-months-from-collapse-without-rapid-action-from-UK-government.aspx (accessed April 2020).

UK Government. Coronavirus Act 2020. 2020. Available online at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2020/7/contents/enacted (accessed July 2020).

Fijiwara D, Dolan P, Lawton R et al. The wellbeing costs of COVID-19 in the UK. 2020. Available at https://www.jacobs.com/sites/default/files/2020-05/jacobs-wellbeing-costs-of-covid-19-uk.pdf (accessed May 2020).

Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain: 14 May 2020. 2020. Available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritain/14may2020 (accessed May 2020).

Office for National Statistics. Which occupations have the highest potential exposure to the coronavirus (COVID-19)? 2020. Available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/whichoccupationshavethehighestpotentialexposuretothecoronaviruscovid19/2020-05-11 (accessed May 2020).

Gamio L. The Workers Who Face the Greatest Coronavirus Risk. 2020. Available online at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/15/business/economy/coronavirus-worker-risk.html (accessed May 2020).

Brooks S K, Dunn R, Amlôt R, Rubin G J, Greenberg N. A systematic, thematic review of social and occupational factors associated with psychological outcomes in healthcare employees during an infectious disease outbreak. J Occup Environ Med 2018; 60: 248-257.

Lai J, Simeng M, Wang Y et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020; DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976.

British Dental Association. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). 2020. Available at https://www.bda.org/advice/Coronavirus/Pages/face-mask-shortage.aspx (accessed May 2020).

Gold J. Covid-19: adverse mental health outcomes for healthcare workers. BMJ 2020; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m1815.

Collin V, Toon M, O'Selmo E, Reynolds L, Whitehead P. A survey of stress, burnout and well-being in UK dentists. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 40-49.

Ayers K M S, Thomson W M, Newton J T, Rich A M. Job stressors of New Zealand dentists and their coping strategies. Occup Med 2008; 58: 275-281.

Chapman H R, Chipchase S Y, Bretherton R. Understanding emotionally relevant situations in primary dental practice 2. Reported effects of emotionally charged situations. Br Dent J 2015; 219: E8.

Consolo U, Bellini P, Bencivenni D et al. Epidemiological aspects and psychological reactions to COVID-19 of dental practitioners in the Northern Italy districts of Modena and Reggio Emilia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 3459.

Shacham M, Hamama-Raz Y, Koleman R et al. COVID-19 factors and psychological factors associated with elevated psychological distress among dentists and dental hygienists in Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 2900.

Sinclair A, Barkham M, Evans C, Connell J, Audin K. Rationale and development of a general population well-being measure: Psychometric status of the GP-CORE in a student sample. Br J Guid Counc 2005; 33: 153-173.

Goulia P, Mantas C, Dimitroula D et al. General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect Dis 2010; 10: 323.

Chua S E, Cheung V, Cheung C et al. Psychological effects of the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong on high-risk health care workers. Can J Psychiatry 2004; 49: 391-393.

Schippers M C, Ziegler N. Life crafting as a way to find purpose and meaning in life. Front Psychol 2019; 13: 2778.

Duffy R D, Dik B J. Research on calling: What have we learned and where are we going? J Vocat Behav 2013; 83: 428-436.

Naidoo D, Schembri A, Cohen M. The health impact of residential retreats: a systematic review. BMC Complent Altern Med 2018; 18: 8.

Fritischi L, Morrison D, Sirangi A, Day L. Psychological well-being of Australian veterinarians. Aust Vet J 2009; 87: 76-81.

Imo U O. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among doctors in the UK: a systematic literature review of prevalence and associated factors. BJPsych Bulletin 2016; 41: 197-204.

Smith C P, Freyd J J. Institutional betrayal. Am Psychol 2014; 69: 575-587.

Smidt A M, Freyd J J. Governmentmandated institutional betrayal. J Trauma Dissociation 2018; 19: 491-499.

Godlee F. Protect our healthcare workers. BMJ 2020; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m1324.

British Dental Association. Dentists: PPE shortages leaving staff at risk and urgent care in jeopardy. 2020. Available at https://www.bda.org/news-centre/press-releases/Pages/PPE-shortages-leaving-staff-at-risk-and-urgent-care-system-in-jeopardy-.aspx (accessed May 2020).

Dyer C. Covid-19: doctors are warned not to go public about PPE shortages. BMJ 2020; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m1592.

Rimmer A. Covid-19: Experts question guidance to reuse PPE. BMJ 2020; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m1577.

Klest B, Smith C P, May C, McCall-Hosenfeld J, Tamaian A. COVID-19 has united patients and providers against institutional betrayal in health care: A battle to be heard, believed, and protected. Psychol Trauma 2020; DOI: 10.1037/tra0000855.

Rajkumar R P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr 2020; 52: 102066.

O'Selmo E, Collin V, Whitehead P. Dental associates' perceptions of their working environment: a qualitative study. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 955-962.

McAlonan G M, Lee A L, Cheung V et al. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can J Psychiatry 2007; 52: 241-247.

Murphy J, Spikol E, McBride O et al. The psychological wellbeing of frontline workers in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic: First and second wave findings from the COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC) Study. 2020. Available online at https://psyarxiv.com/dcynw/ (accessed December 2020).

Maunder R G, Lancee W J, Balderson K E et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. J Emerg Infec Dis 2006; 12: 1924-1932.

NHS Digital. Dental Earnings and expenses estimates 2018/19. 2020. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/dental-earnings-and-expenses-estimates/2018-19/england (accessed August 2020).

General Dental Council. Registration report - May 2020. 2020. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/docs/default-source/registration-reports/05-registration-report---may-2020.pdf (accessed June 2020).

Acknowledgements

Victoria Collin and Ellena O'Selmo are joint first authors.

We would like to thank all of those who contributed to the research. They graciously made their time available and reflected openly on difficult questions.

This work was funded by the BDA Trust and the Shirley Glasstone Hughes Trust Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Collin, V., O´Selmo, E. & Whitehead, P. Psychological distress and the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK dentists during a national lockdown. Br Dent J (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2592-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2592-5

This article is cited by

-

A systematic review of dentists' psychological wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Dentists' preparedness to provide Level 2 services in the North East of England: a mixed methods study

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Psychometric evidence of a perception scale about covid-19 vaccination process in Peruvian dentists: a preliminary validation

BMC Health Services Research (2022)

-

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of dentists in Wales

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Moving on

BDJ In Practice (2022)