Abstract

Introduction The use of apps has increased in recent years, especially in healthcare. Due to apps being largely unregulated, the quality and accuracy of the information provided can be variable.

Aim To assess the availability of patient-focused oral hygiene apps and profile the characteristics of the most popular apps on Apple's 'App Store' and, on Android, 'Google Play'.

Method Oral hygiene-related search terms were used to identify apps on these platforms. Detailed information for the 20 most popular apps for each search term was recorded.

Results In total, 1,075 apps were identified with fewer apps available on the App Store than on Google Play. The 20 most popular apps for each search term focused on providing oral hygiene information, were free of charge and were developed after 2015. No apps contained information regarding whether they were approved by official organisations and if effectiveness or acceptability testing had been conducted. App ratings were variable and unrelated to the quality and accuracy of the information.

Conclusion Due to a lack of professional regulation, there is a risk that patients may access inaccurate information via apps. Therefore, evaluation, validation, and quality assessment of healthcare apps is needed before recommending these to patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

Provides an overview of the availability of patient-focused oral hygiene apps.

-

Profiles the most popular patient-focused oral hygiene apps.

-

Highlights the shortcomings of the information provided within apps and the lack of regulation of this information.

Introduction

Mobile phones are potentially an invaluable tool in improving patient care. They are readily available in Western Europe, and are very versatile.1 Mobile communication, the internet and smartphones are an integral part of many people's lives and this often involves the use of mobile applications. A mobile application, most commonly referred to as an 'app', is designed specifically to run on small, wireless computing devices such as smartphones.2 Apps are usually small, individual software units with limited functions; therefore, each app provides limited and isolated functionality such as a game, calculator or mobile web browsing.2 The specificity of apps is part of their desirability because they allow consumers to customise what their devices are able to do.

The use of apps was originally popularised by Apple and then by Google (Android), who both launched application stores in 20083,4,5,6,7 and at present these are the most commonly used mobile application marketplaces.8 The number of apps available has grown year-on-year. In the first quarter of 2018, there were approximately 3.8 million Android apps and 2.2 million Apple apps available to download.8 In 2017, there were approximately 197 billion app downloads which had increased from 149 billion in 2016.8 In 2017, it was found that the average American spent 2.3 hours per day on digital media on their mobile phone. It has also been found that 18-24-years-olds are the age range that spends the most time on apps, spending, on average 93.5 hours per month using apps.8

The use of apps in healthcare and dentistry

The increasing availability of apps has seen their use in healthcare increase significantly in recent times. There are currently over 97,000 mobile apps that are related to health and fitness and the top ten rated health apps are downloaded approximately four million times a day.9 Bohn et al.10 assessed patient preferences relating to the use of apps as dental education aids and found that patients liked using apps and found educational apps to be a valuable tool to enhance patient-provider communication in the dental setting.

There are many advantages to the use of apps in healthcare, including easy access to information and potentially improved patient engagement and compliance with treatment.6,11,12,13 Despite these advantages, there are also some limitations to the use of apps, most notably that the information on apps may be unregulated and, therefore, some apps accessed by patients may contain significant inaccuracies. The potential advantages and disadvantages of apps are summarised in Table 1.

The aim of this study was to assess the availability of patient-focused apps on oral hygiene. In addition, the characteristics of the 20 most popular apps available on the App Store and Google Play store have been profiled. Oral hygiene was selected as the focus for this study because it is a common area of interest for patients and is of relevance to all dental professionals.

Method

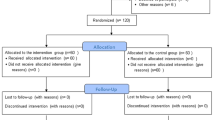

Common terms used to describe either oral hygiene or those to seek oral hygiene advice were selected as search terms and piloted. Search terms included: 'oral hygiene', 'dental hygiene', 'brushing', 'proper brushing', 'tooth brushing', 'teeth cleaning', 'cleaning teeth', 'dental flossing', and 'interdental brushing'. Following the pilot, it was found that some of the search terms were insensitive and retrieved mainly non-dental apps; therefore, the final search terms used were: 'oral hygiene', 'dental hygiene', 'tooth brushing', 'teeth cleaning', 'dental flossing' and 'interdental brushing'. These were entered into the App Store and Google Play store search functions on 25 July 2018, and the results recorded and analysed. Clinician-focused apps, dental education apps aimed at students or dental professionals, and non-English apps were excluded. All other apps were downloaded and assessed for inclusion by two assessors (RB and KP), and a third assessor (MOS) was consulted to mediate and achieve a consensus in cases of disagreement.

For each search term, the total number of apps meeting the inclusion criteria was recorded. The characteristics of the 20 most popular apps was determined by identifying the highest ranking apps that met the inclusion criteria for each search term on both the App Store and Google Play store. These were then assessed in more detail, with information collected including main app function, app rating, cost and the year of development.

Results

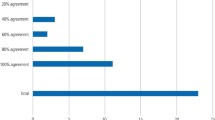

A total of 1,075 apps were retrieved, however a number of apps were duplicated across the different search terms and stores. The total number of apps retrieved for each search term is shown in Table 2; this shows that there are a large number of apps available for each search term and that generally more apps are available via Google Play when compared to the App Store. 'Tooth brushing', 'teeth cleaning' and 'oral hygiene' search terms resulted in the highest number of apps being retrieved. Table 3 summarises the characteristics of the 20 most popular apps retrieved for each search term. It can be seen that, for all search terms, the majority of apps were developed after 2015, were focused on the provision of oral hygiene instruction and were free of charge.

Discussion

At present, there are a large number of patient-focused apps available for oral hygiene-related search terms. An analysis of the 20 most popular apps (Table 3) highlights that a number of approaches have been utilised by app developers to elicit an improvement in oral hygiene. These include the provision of oral hygiene advice, ability to time toothbrushingv and gamification. Utilising a variety of approaches in a single app may be better for improving adherence to effective oral hygiene practices. For example, knowledge provision may increase motivation, and the ability to time toothbrushing with a summary of frequency and duration of toothbrushing episodes may allow for self-monitoring and act to motivate individuals whereas gamification may improve engagement with apps.

Unsurprisingly, the majority of apps were designed to provide oral hygiene advice and the vast majority of the apps were available free of charge. All apps requiring a payment cost less than £2.00. The availability of inexpensive apps helps to limit potential access barriers; this is particularly important as it has been shown that apps are often primarily chosen according to price, with users frequently preferring free apps to those requiring a payment.6 App analysis did not reveal any independent dental or oral health organisation approval for development and publication, and there was no indication on research testing of the apps. Furthermore, none of the apps profiled clearly stated if they had been developed based on theoretical models of behaviour change. This is significant, as interventions designed on the basis of behavioural theory have been shown to be more effective than those that are not.14,15

During the conduct of this study, it became apparent that the apps retrieved were more likely to have a rating on the Google Play store than the App Store. It is unclear if the overall rating of an app on both platforms is simply an average of the user review ratings or if any other factors are considered. Moreover, information on the number of downloads and therefore number of potential app users was not available on the App Store, however the Google Play store provided download data in categories, such as over 10,000 or over 100,000 downloads. Due to a lack of precise download data comparing the number of downloads for each app for the different search terms and for the different platforms was not attempted.

Although many of the apps had a rating, these ratings were an accumulation of user reviews and not an objective assessment of app quality, or the accuracy of the information contained within the apps. Therefore, at present it is not possible to comment on the quality, effectiveness and accuracy of the apps retrieved. However, apps do appear to be acceptable; one study concluded that 80% of patients reported that the 'Brush DJ' app motivated them to brush for longer and 92.3% would recommend the app to their friends.16 Furthermore, in the field of orthodontics, apps have been shown to be effective in improving appointment attendance, oral hygiene and in reducing appliance breakages.15,17,18,19

Given the availability of smartphones, and the many potential advantages of apps, the role of this technology in supporting dental patients is invaluable. Nevertheless, in contrast to websites and other modes of information provision, the development of mobile phone apps to support dental care can be said to be in its infancy. There are a number of factors that need to be considered when developing and recommending apps for patients, these are detailed later in this article.

Quality and accuracy of information

The current lack of professional regulation for app development means that there may be much variability in the quality and reliability of the information contained within apps. To be available on Google Play and the App Store, apps are submitted for consideration and theses apps are then assessed and checked against many factors including usability and desirability of the app; however, the accuracy of app content is not assessed.3,4 A review of oral health app content concluded that the quality of apps was generally poor and that none of the app developers were oral health experts or cited any sources for the information contained within the apps.20 In addition, it is not clear whether patients' perspectives are taken into account when developing apps. Therefore, in future, qualitative research, focused on interviewing patients about their use of apps and the information they would like apps to contain, would be extremely useful and would be a beneficial area for future research.

Given the lack of professional control surrounding the development of and information contained within apps, it is prudent for dental health professionals to assess the quality and accuracy of apps before recommending them to patients. The NHS has developed an app library.21 This is an online resource listing healthcare apps that have been approved by the NHS and requires developers to evidence that their app passes numerous NHS tests,22 including:

- 1.

Eligibility

- 2.

Clinical safety

- 3.

Data protection

- 4.

Security and usability.

At present, the only dental app within the library is 'Brush DJ' which contains videos on oral hygiene techniques and a toothbrushing timer. This app is free of charge and was created in 2011; it has been downloaded over 100,000 times.8 To facilitate easy access to quality-assured apps for patients, it would be beneficial to create a dental app library similar to the existing NHS library but solely focused on dentistry. This app library could be hosted by an approved dental or medical organisation such as the British Dental Association or one of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Another tool available for professionals to assess the quality of healthcare apps is the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS).23 This is a validated tool to assess app functionality, aesthetics, information and engagement; these domains are rated from one to five, and mean scores are then calculated. It is important to note that this is a subjective, questionnaire-based assessment tool and is, therefore, limited in assessing the accuracy and validity of the information provided in the app.

In contrast, there are a number of validated healthcare assessment tools available to help with the assessment of information quality of websites. Two commonly used tools include: the LIDA24 tool which assesses usability, validity and accessibility of websites;25 and the DISCERN26 tool which assesses the quality of health information and the reliability of websites.27

Relevant legislation and guidance

The General Dental Council

In 2013, the General Dental Council (GDC) published Guidance on Advertising,28 which includes information placed on websites. This document specifies that websites created by GDC registrants should be: accessible, not misleading, and that any dental services provided are clearly explained. If these guidelines are not adhered to, individuals risk being brought before the GDC's fitness to practise committee for advertising false information. Although this guidance does not explicitly extend to apps, it would be prudent for dental care professionals developing apps/recommending apps to ensure that they adhere to this advice in the absence of other guidance.

Advertising Standards Authority

The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) is a regulatory organisation for the advertising industry29 and it has a code of advertising practice which covers advertising through non-broadcasting media, including online and print. In recent times, the ASA have highlighted that dental patients are often presented with inaccurate and misleading claims relating to dental treatment and have taken action.30,31,32,33 It would, therefore, be prudent for dental care professionals developing apps and recommending apps to ensure that they adhere to this advice in the absence of other guidance.

General Data Protection Regulation

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was implemented on 25 May 2018 and applies to the processing of data within the European Union.34 GDPR outlines a number of requirements for the processing and handling of data including how and what private data is stored. Although GDPR is not a specific tool designed to assess apps or websites, those who develop such resources must comply with GDPR requirements. Prior to the implementation of GDPR, in December 2017, it was reported that over 55% of apps may not comply with the new guidelines.35 Therefore, following the introduction of GDPR, it is now hoped that at least some aspects of the information contained and stored on apps will now be governed, which will increase the security of such data.

Conclusion

Since the introduction of apps in 2008, their popularity and use has increased rapidly on a global scale. These advances have been possible due to improvement and greater access to mobile technology and internet access becoming ubiquitous. Although healthcare apps have numerous advantages and may improve patient outcomes, many are currently being used without a full understanding of their advantages and disadvantages.36 Due to a lack of professional regulation, there is a risk that patients may access inaccurate content via apps.20 Therefore, evaluation, validation, and quality assurance is needed, as well the need to develop best practice standards and guidelines for app use. Furthermore, ensuring apps are quality-assured and theoretically grounded before use and that ongoing regulation is undertaken is essential.20,36

References

Cartesian. The Rise of Mobile Phones: 20 Years of Global Adoption. 2015. Available at https://blog.cartesian.com/the-rise-of-mobile-phones-20-years-of-global-adoption (accessed March 2019).

Wallace S, Clark M, White J. 'It's on my iPhone': attitudes to the use of mobile computing devices in medical education, a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2012; 2: e0019009.

Apple. App Store. Available at https://www.apple.com/uk/ios/app-store/ (accessed March 2019).

Google. Google Play. Available at https://play.google.com/store?hl=en_GB (accessed March 2019).

Chase J. Healthcare Professionals: iPads and other drugs. 2013. Available at https://www.mmm-online.com/home/channel/features/healthcare-professionals-the-ipad-and-other-drugs/ (accessed March 2019).

Murfin M. Know your apps: an evidence-based approach to evaluation of mobile clinical applications. J Physician Assist Educ 2013; 24: 38-40.

Yoo J H. The meaning of information technology (IT) mobile devices to me, the infectious disease physician. Infect Chemother 2013; 45: 244-251.

Statista. Mobile App Usage Statistics & Facts. Available at https://www.statista.com/topics/1002/mobileappusage (accessed March 2019).

Y Media Labs. The Future of Healthcare: How Mobile Medical Apps Give Control Back to Us. Available at https://ymedialabs.com/future-of-healthcare (accessed March 2019).

Bohn C E, McQuistan M R, McKernan S C, Askelson N M. Preferences Related to the Use of Mobile Apps as Dental Patient Educational Aids: A Pilot Study. J Prosthodont 2018; 27: 329-334.

Aungst T D. Medical applications for pharmacists using mobile devices. Ann Pharmacother 2013; 47: 1088-1095.

Divali P, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Baker R. Use of personal digital assistants in clinical decision making by health care professionals: a systematic review. Health Informatics J 2013; 19: 16-28.

Mickan S, Tilson J K, Atherton H, Roberts N W, Heneghan C. Evidence of effectiveness of health care professionals using handheld computers; a scoping review of systematic reviews. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e212.

Webb T L, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behaviour change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behaviour change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res 2010; 12: e4.

Zotti F, Dalessandri D, Salgarello S et al. Usefulness of an app in improving oral hygiene compliance in adolescent orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod 2016; 86: 101-107.

Underwood B, Birdsall J, Kay E. The use of a mobile app to motivate evidence-based oral hygiene behaviour. Br Dent J 2015; 219: E2.

Li X, Xu Z R, Tang N et al. Effect of intervention using a messaging app on compliance and duration of treatment in orthodontic patients. Clin Oral Investig 2016; 20: 1849-1859.

Alkadhi O H, Zahid M N, Almanea R S, Althaqeb H K, Alharbi T H, Ajwa N M. The effect of using mobile applications for improving oral hygiene in patients with orthodontic fixed appliances: a randomised controlled trial. J Orthod 2017; 44: 157-163.

Lima I F P, de Andrade Vieira W, de Macedo Bernardino Í et al. Influence of reminder therapy for controlling bacterial plaque in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Angle Orthod 2018; 88: 483-493.

Tiffany B, Blasi P, Catz S, McClure J B. Mobile Apps for Oral Health Promotion: Content Review and Heuristic Usability Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018; 6: e11432.

NHS. Apps Library. Available at https://apps.beta.nhs.uk/ (accessed March 2019).

NHS. How we assess apps. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/apps-library/how-we-assess-apps/ (accessed March 2019).

Stoyanov S R, Hides L, Kavanagh D J, Zelenko O, Tjondronegoro D, Mani M. Mobile App Rating Scale: A New Tool for Assessing the Quality of Health Mobile Apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015; 3: e27.

Minvervation. LIDA Tool. 2012. Available at http://www.minervation.com/category/lida/ (accessed March 2019).

Patel U, Cobourne M T. Orthodontic extractions and the internet: quality of online information available to the public. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011; 139: e103-e109.

DISCERN. Available at www.discern.org.uk (accessed March 2019).

Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999; 53: 105-111.

General Dental Council. Guidance on advertising. 2013. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/api/files/Guidance%20on%20advertising%20(Sept%202013).pdf (accessed March 2019).

Advertising Standards Authority. Who we are and what we do. Available at https://www.asa.org.uk/transparency/who-we-are-and-what-we-do.html (accessed March 2019).

Healthcare News. GDC joins forces with Advertising Standards Authority. 2014. Available at http://www.smile-onnews.com/news/view/gdc-joins-forces-with-advertising-standards-authority (accessed March 2019).

Advertising Standards Authority. ASA Ruling on 15 Dental. 2017. https://www.asa.org.uk/rulings/15-dental-a16-365575.html (accessed March 2019).

Advertising Standard Authority. ASA Ruling on IGDP Ltd. 2017. Available at https://www.asa.org.uk/rulings/igdp-ltd-a16-348854.html (accessed March 2019).

Advertising Standards Authority. ASA Ruling on OrthoAccel Technologies Inc t/a AcceleDent. 2018. Available at https://www.asa.org.uk/rulings/orthoaccel-technologies-inc-a17-393373.html (accessed March 2019).

Information Commissioner's Office. Available at www.ico.org.uk (accessed March 2019).

Safe DK. December 2017 Mobile SDKs Data Trends Report in the Android Market. 2017. Available at http://mobile-sdk-data-trends.safedk.com/full-report-Dec-2017 (accessed March 2019).

Misra S, Lewis T L, Aungst T D. Medical application use and the need for further research and assessment for clinical practice: creation and integration of standards for best practice to alleviate poor application design. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149: 661-662.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parker, K., Bharmal, R. & Sharif, M. The availability and characteristics of patient-focused oral hygiene apps. Br Dent J 226, 600–604 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0197-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0197-7

This article is cited by

-

Smartphone applications as a tool to improve children’s brushing habits

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2023)

-

Impact of smartphone application usage by mothers in improving oral health and its determinants in early childhood: a randomised controlled trial in a paediatric dental setting

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2022)

-

Patient focused oral hygiene apps: an assessment of quality (using MARS) and knowledge content

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

A systematic review to assess interventions delivered by mobile phones in improving adherence to oral hygiene advice for children and adolescents

British Dental Journal (2019)