Abstract

Aims To establish what work a sample of Overseas Registration Examination (ORE) registrants were undertaking and understand what had facilitated or impeded them from finding suitable employment as dentists. Method An online questionnaire, consisting of both closed and open questions, was used to capture data from a population of 1,106 former ORE candidates who passed the examination between 2009 and 2014 and were registered by the General Dental Council (GDC). The data were analysed and presented in the form of tables, figures and a presentation of the major themes that emerged from the responses. Results There was a 42% response rate. Seventy-one percent of respondents were employed as dentists in the UK, with the majority providing a mixture of private and NHS patient treatment. Most who were not working as dentists were actively seeking training places. Additional themes that were identified included: the availability of Dental Foundation/Vocational Training places; poor employment practices; perceptions of the strengths and weaknesses of the ORE; and some ideas about the future responsibilities of the GDC. Conclusions This survey has highlighted some difficulties that many ORE registrants face finding suitable work as dentists. Stakeholders should be aware of these challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

Describes the work undertaken by ORE-route registered dentists in the UK.

-

Provides insight into the challenges many faced finding suitable Performers List Validation by Experience places and subsequent employment.

-

Raises awareness among multiple stakeholders of these challenges and the role of the GDC in relation to the ORE.

Introduction

At present, all dentists who are nationals of European Economic Area (EEA) countries, and who have gained a primary dental qualification after training in a dental school within the EEA, can apply to register with the General Dental Council (GDC) if they are of good professional standing. With some exceptions, dentists from other countries are required to pass the Overseas Registration Examination (ORE)1 if they wish to register with the GDC. The ORE advisory group (OREAG) is responsible for the quality assurance of the ORE.1 It does this by adopting recognised academic approaches to ensure that the examination is conducted according to best practice. To pass the examination, overseas-qualified dentists must demonstrate standards of knowledge, skills and professional attitudes consistent with those expected of recently graduated UK dentists. However, the ultimate test of the examination's fitness for purpose is the performance of ORE-route registrants in the workplace. To investigate that issue more closely, it is necessary to know more about the progression routes for those dentists who gain their GDC registration through the ORE route. This study was therefore carried out to look at that specific issue in some detail, and it involved a unique survey of all dentists who passed the ORE between 2009 and 2014.

New graduates who have trained in the UK follow funded dental foundation training schemes (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) or vocational training programmes (Scotland). These schemes provide a supportive, mentored environment for a period of one year while additional training is undertaken. Successful completion of training is obligatory if a dentist wishes to be enrolled on a Performers List (or equivalent) to work in the NHS. While there is no guarantee of UK-trained dentists being successful in finding a training place post-graduation, the process can be considerably more difficult for many overseas applicants. Overseas dentists who have passed the ORE can apply for Performers List Validation by Experience (PLVE), formerly known as Dental Foundation Training Equivalence (DFTE) or Vocational Training Equivalence (VTE), following a period of approved further training. We use 'PLVE' throughout the text accepting that this is recently introduced terminology; the ORE-dentists surveyed will have most likely encountered 'VTE' and responded accordingly. Therefore, the training experiences of ORE-route registered dentists was one of the key issues investigated through this study.

The two main objectives of the survey were to discover:

-

1.

The employment history of individuals who followed the ORE route to registration

-

2.

Their personal experiences in accessing training places and entering the workforce.

The results of this survey, which are presented in this paper, shed new light upon the formerly neglected topic of the experiences of overseas-qualified dentists who take the ORE as a means of seeking to further their dental careers in the UK.

Method

Selection of cohort

Between 2007 and 2009, dentists entering the GDC register via the statutory examination could potentially have passed components of both the ORE and its predecessor the IQE (International Qualifying Examination), under transitional arrangements that followed the introduction of the ORE. To ensure that the cohort surveyed had passed only ORE components, the invitation to participate was restricted to those who were successful in the examination from the beginning of 2009 to the end of 2014. Therefore, 1,106 individuals were identified as fitting that profile as recorded on the GDC dentists register.

Data capture

An online questionnaire was chosen as an efficient means of collecting the data from such a large sample. Most questions were 'closed', but a small number of 'open' questions were included because it was acknowledged that some responses were likely to be diverse, complex and contextually dependent. It was felt that capturing this information in the respondents' own words would provide richer data than could be achieved with closed questions.

The questions in the initial draft were developed through collaboration between the GDC's research team and two members of the OREAG. Informal discussions with a small sample of ORE registrants, and members of the profession with first-hand experience of advising and/or working with ORE-registered dentists, refined the content by providing additional stakeholder perspectives.

The questionnaire comprised 20 questions and was split into three sections. The first section gathered background demographic information; the middle section focused on employment history, training needs and professional organisations that had provided support; and the final section was designed to explore registrants' personal experiences of finding training places and subsequently entering the workforce. The last question asked about individuals' willingness to participate in future research. The survey questionnaire is included in the supplementary information.

The survey was sent electronically to all eligible registrants in November 2015 and remained 'live' for a three-week period. A short covering letter was included to explain the purpose of the research with an emphasis on anonymity, which was guaranteed for all respondents. Participation was voluntary. Reminders were sent two weeks after first issue and a few days before the closing date in mid-December.

Data management

Descriptive data from seventeen questions were organised into a series of tables and figures. The data from two further open questions were analysed thematically.

Results

Four hundred and sixty-five ORE registrants replied; a return rate of 42%. Three hundred and fifty-seven (77%) of respondents were female. Primary qualifications were from 40 different countries, but most obtained their first dental degree/diploma from the following five: India 53%, Pakistan 14%, Nigeria 3.9%, Iraq 3.7% and Egypt 3%. Most registrants had passed both parts of the examination within two attempts at each component, part 1: 445 (96%), part 2: 357 (77%). The smallest group of respondents comprised those who passed the examination in 2011.

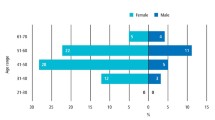

At the time of the survey, 330 registrants (71%) were employed and working as dentists (Table 1). One hundred (21.7%) were either employed but not working as dentists or were unemployed. A further 24 (5%) were not resident in the UK. Two hundred and seventy-two registrants who had found employment as a dentist were working either in independent or corporately-owned practices (Table 2). Two hundred and forty-nine respondents who were working as dentists (80.1%) said they were providing a mixture of private and NHS patient treatment. Thirty-three (10.6%) were working exclusively in the private sector and 29 (9.3%) were providing NHS treatment only. The employment status of those not working as a dentist is shown in Figure 1.

There were 109 comments left for 'other'. Responses were varied, but for those in employment, the most frequent answers were: working as a hygienist (13) and working as a dental practitioner in another country (10). Fifty-five respondents stated that they were unemployed, with many commenting that they were actively seeking Performers List Validation by Experience (PLVE), also known as Vocational Training by Equivalence (VTE), places to allow them to work as dentists. One hundred and eighty-nine registrants had secured a training place that led to the allocation of a performer number within twelve months of first registration, but for many the process took much longer (Table 3).

Ninety-eight (35%) respondents answered 'yes' to the question about additional training being recommended as part of their PLVE placement. Respondents could select all that applied from a list provided (see supplementary information). Responses were therefore recorded for more than one category. Details of training recommended are provided in Table 4.

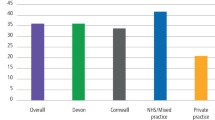

The survey asked about the length of time between ORE dentists finishing PLVE training and finding paid employment that allowed them to work unsupervised. The results are set out in Figure 2. One hundred and ninety-eight (77%) respondents who answered this question were able to find employment as a dentist within six months of finishing PLVE, and a further 47 (18.2%) within one year. Three individuals (1%) waited more than two years.

Respondents could select all that applied from a list provided (see supplementary information) when asked about whom they had approached for employment advice. Responses were therefore recorded for more than one category and are shown in Figure 3. Friends, colleagues or mentors were most frequently consulted. Between 15% and 20% had asked post-graduate deaneries and/or the British Dental Association for help. The deaneries most frequently approached were based in London and the West Midlands. Listings for the 'other' category included dental practices, recruitment agencies and a variety of professional organisations' websites.

Question 17 was a follow-up question that asked respondents to identify any postgraduate deanery, dental school or professional body they had approached for help. The response (n = 82) was varied, but the deaneries most frequently asked for advice were as follows: London (21), West-Midlands (13), East of England (8) and Wales (8). The Dental Institute at King's College London was the only dental school that featured significantly (7).

Most (91%) ORE registrants who responded to the survey answered open questions 18 and 19 (see supplementary information). Question 18 asked about finding employment in the UK and the challenges faced before and after passing the ORE. Question 19 invited other comments about respondents' careers in the UK. There was some overlap for responses with the previous question, particularly in relation to PLVE placements. The latter have therefore been included in the analysis for question 18.

The authors do not have the means to check the veracity or validity of the comments returned by participants. However, several themes did emerge quite strongly. These were:

-

1.

Accessing PLVE training

-

2.

Finding employment

-

3.

Potentially poor employment practices in the workplace.

These are discussed below. 'Direct quotes' are presented alongside as appropriate to aid interpretation.

PLVE placements

Four main areas of concern were raised:

-

1.

Availability

-

2.

Funding

-

3.

No centralisation of information

-

4.

Lack of understanding about the ORE and 'equivalence training' among the profession.

Of the 425 comments collected through question eighteen, 188 (44%) included something about the difficulty of finding a PLVE placement which was identified as the main barrier to finding suitable employment. The application process was noted to be unwieldy and delays completing the required paperwork by deaneries sometimes led to an applicant losing a place on a scheme. A small number of individuals failed to secure any place despite repeated efforts. Lack of funding was perceived as a major obstacle. There was no financial incentive for trainers to accept ORE registrants in their practices. The onus had been on the registrant to find a place, but without funding this had proved difficult. Some had succeeded only through existing contacts and connections. There was a perception of a general lack of information about how to locate a suitable training practice, and no 'central list' of those who would be willing to accept ORE registrants. While some were given good advice by their local deaneries, some remarked that they had found them unhelpful:

'No help for us whatsoever, left in the jungle all alone to find VT, no central place to apply to get the VT placement.'

'Deaneries have no specific outline on what is expected from a VTE candidate & no clear guidance for trainers or trainees.'

'We don't have any support of deanery (funding) or any organisation. Even if we join hands and try to take some action and submit our plea, no one seems to hear/respond.'

'Deaneries make it really difficult to process a VTE application.'

For those who succeeded in finding a placement, some commented that there were key differences between PLVE (formerly VTE) training and the training available for UK graduates. For example, UK graduates can attend funded study days, while ORE registrants had to fund their own courses. There were concerns that ORE registrants had to accept reduced wages, unpaid work and in some cases were required to pay practice principals for work:

'Me and my friends were exploited while doing equivalence, I was not getting paid for two-three months and then the employer used to cut my wages…I finally had to leave the practice.'

'People who want to employ overseas dentists take advantage of our vulnerable situation and make us work for little or nothing. Someone needs to regulate this.'

'We need more support and we need a body that is responsible for us. Someone who we can complain to if employers take advantage of our vulnerable situation. It is absolutely vital that something is done about this!'

Some seemed to be caught in a 'Catch-22' situation with registrants finding it impossible to find a PLVE place without providing evidence of an NHS performer number, yet being unable to access the latter without a training place. This links to comments about a lack of awareness within the profession about the examination, the standard required to pass it, and how PLVE training sits alongside it:

'Most of the British dentists don't even know what a VTE is.'

'Many employers or principal dentists do not have any idea how to employ us or the process of VTE. Please do make some awareness or let everyone know that they can employ us.'

'They [people who deal with VTE applications] knew nothing about ORE. All I heard was "sorry we don't put these rules, maybe you need to ask the GDC why they made you do these exams".'

Finding employment

Some respondents commented that employers were looking for previous UK work experience, particularly those in the private sector, where finding work was noted to be difficult. There was sometimes an expectation that places should be available in their local towns and cities, as illustrated by the following comments:

'Yes, [the difficulty of] finding a job in London which offered VT equivalence.'

'Difficult to get job close to my house.'

There were examples where being able to relocate to a different part of the country brought dividends.

'It was hard to get the first job. I had to relocate from London to Norwich, but that turned out for the best in the end as I had an amazing mentor who also offered me a job post-VTE. It was a very important learning curve and exposure to dentistry in UK.'

In the absence of paid employment in the area where they lived, some had been advised to work unpaid, which they could not afford to do. Not having a performer number and the difficulty of obtaining one was identified as a major barrier to finding a job as a dentist. However, it should be noted that not all responses were negative. Seventy respondents (16%) reported that they had experienced little or no difficulty finding training places or employment:

'I was accepted as a VDP candidate from the first attempt, and afterwards finding jobs were easy.'

'Had no problem with the exam or finding employment.'

'Everything went smooth, and the experience gained through the ORE journey was priceless as this really prepared me for UK dentistry (very different from my experience in France and Algeria).'

'My past experience from my original country helped a lot, in addition I have obtained MFDS while I was preparing for ORE exam, all these paved the way to get a good job offers.'

Poor employment practice post-PLVE

Some respondents felt they had been treated differently from UK graduates. There were comments about ORE registrants being asked to sign long-term contracts with their employer and claims of being paid at a lower rate than their UK-trained colleagues. One respondent was advised that she should not get pregnant during the following eighteen months. Some talked about feeling less appreciated than their UK counterparts and the impact this had on their well-being:

'Sometimes employers assume less qualification due to the fact that I have qualified abroad although I have taken the ORE and completed one-year VT.'

'Being foreign was an issue, the stigma of "being different".'

'Not having qualified here, so the assumption that I'm less skilled by fellow colleagues.'

'The damage to one's self esteem is quite considerable. You end up questioning yourself after a while.'

The main themes that emerged from question 19 (other than PLVE placements) were:

-

1.

The examination

-

2.

The role of the GDC.

These are discussed below. Direct quotes are presented alongside to aid interpretation.

The ORE

Mixed views were expressed about the ORE. Some questioned its value for money. Despite that, many felt it was a good test of knowledge and skills; and worthy of higher recognition because many employers did not appreciate its equivalence to a UK dental degree:

'The ORE should be a qualification or a degree rather than an exam.'

'People are not aware that ORE is a very stringent and rigorous exam that requires uncompromising skill on behalf of the candidate and the candidate who passes ORE has the necessary baseline skill that can be further polished with proper guidance.'

'The ORE examination is a rigorous and competitive method of testing competencies for overseas dentists…the local dental clinic owners do not know the level of expertise needed to pass this examination.'

Indeed, there were some very positive comments about the examination.

'I always wanted to state this, I'm one of the few ORE candidates that thinks that the ORE is a great opportunity to polish skills and prepare to the stressful job of being a dentist is such a busy atmosphere we face in the UK. I always felt that I was in a higher level than my colleagues in the different practices I worked in, and I would like to thank the GDC for the great effort to produce ORE.'

'I am very very fortunate to find employment…the ORE prepared me better for work in the UK than an EU candidate because after the ORE you are well versed in legislative matters as well as the idiosyncrasies of dental practice in the UK.'

However, this feeling was not unanimous. There were those who felt that it did not test all the clinical skills needed in general dentistry, or the knowledge required for working in NHS dentistry. As a result, additional courses were required to understand the latter at extra cost.

The role of the GDC

There was a general view that the GDC was not doing enough to support ORE registrants and had failed to make clear the difficulties of obtaining a visa and finding work in the United Kingdom. There was a call for better signposting of PLVE placements and standardisation of practices and policies around employing ORE dentists. There was also some support for a cap on the numbers sitting the ORE. Some respondents reflected that they regretted doing the ORE because of the lack of career opportunities available post-assessment. There were also strong feelings about paying the registration fee when unemployed and with no guarantee of a job:

'If there aren't enough VTE placements then reduce intake for part 1, no point having qualified people when they can't get a VTE.'

'STOP conducting exams if there is no way to provide the performer number…principal dentists are abusing the system.'

'Had there been more information about what the whole registration involves or at least like testimonials or something on the GDC website, many people would think twice before going through this whole process.'

Most respondents agreed that they would be prepared to be involved with future research.

Discussion

This survey has broken new ground by giving valuable insights into the real-life experiences of a significant group of dentists who gained the right to be registered in the UK via the ORE route. Given the disparate nature of the individuals being studied, the response rate of 42% that was achieved in this survey is seen as being sufficient for the findings to warrant attention. The lowest response rate was from those who passed the ORE in 2011. The reason for that is unclear. The pass rate for 2011 was not unusual. However, there were just two iterations of the part 2 examination that year, so there may have been a smaller pool of registrants than for other years.

There are many possible reasons for individuals not being able to respond to a survey. Some may not have received the original or follow-up messages. Despite reassurances that individuals would not be identified, a proportion may have felt uncomfortable sharing their experiences via an online platform. Low response rates are in fact quite common for surveys of dental practitioners. Tan and Burke2 reviewed seventy-seven academic publications that had used a questionnaire sent to dentists. They found response rates to be very variable, from just 17% to 100%. A more recent online survey of recent dental graduates' knowledge of restorative dentistry training and service provision gathered just 100 responses from a potential pool of 4,000.3

Sending follow-up reminders to the target population is one way of increasing the response rate; a strategy that was used in this survey. Low response rates create uncertainty that the respondents accurately reflect the views of the target population and that some groups might be underrepresented. ORE-route registered dentists originate from many different countries, with India the most frequently represented (43%), a demographic reflected in this survey. Three-quarters of individuals who were eligible to join the register via the examination route since 2009 were female. The fact that seventy-seven per cent of survey respondents were female might therefore be expected. Low response rates do not necessarily indicate bias.4 Nevertheless, the authors acknowledge the possibility that responders were more likely to have negative 'issues' they wished to address than those who did not reply to the invitation.

Just over 71% per cent of respondents were working as dentists at the time the survey was conducted. Independently-owned practice was most commonly recorded as a place of work, followed by the corporate sector. The majority were providing a mixture of NHS and private patient treatment; a pattern of practice not dissimilar to that previously reported for UK registrants as a whole.5 Just over a third of dentists who undertook the ORE route to registration, and were working in the NHS, had found a PLVE place within six months of registration, and just under another third within one year. For the remainder, the process took much longer, with 11% waiting more than two years.

For those who had completed PLVE training, nearly 77% had found paid employment that allowed them to work unsupervised within six months, and a further 18% within a further six-month period. Unfortunately, the process took much longer for the remaining 5%, with some respondents waiting more than two years before securing employment. This is not ideal, as they may have become deskilled in the interim period. However, it should be remembered that the profile of the average individual following the ORE route to registration is not identical to that of recent a UK graduate. Many already have years of experience gained in their own countries, or from working in UK hospitals following temporary registration. Moreover, skill retention and decay following non-use is a complex area with many mitigating factors.6 It is thought to be influenced by the degree of original learning or 'overlearning' (the extent to which someone has learned and practised a skill beyond initial proficiency).7 The frequency and intensity of practise needed to maintain skills is unclear, but skill decay is more likely to be rapid in novice providers,8 so the decline may not be as great a problem as anticipated.

A few respondents felt that by passing the ORE they had already demonstrated linguistic competence, and that the GDC should provide a certificate as proof of that. This could be used when applying for jobs with primary care trusts and would save the expense of renewing the International English Language Testing System certificate, which is valid for two years only. However, it should be appreciated that this would effectively mean the regulator awarding a 'qualification', which is outside its remit.

Given the comments about the variation in the support provided by deaneries and other professional organisations, it was perhaps not surprising that the majority said they had turned to friends and colleagues for help. This may have been someone who had already gone through the same process and could provide 'expert' knowledge of the system and how best to navigate a way through it.

Nearly a third of respondents were on the register but not in employment as dentists. Some remained connected to the world of dentistry and were working as hygienists and practice managers. Others had found work in unrelated fields. However, many were simply unemployed and actively seeking a PLVE placement. Responses to the open questions provided rich data about the difficulties of securing a PLVE training place that would lead to an NHS performer number. It can take several years to go through the whole examination process, at a cost of thousands of pounds. In this study, many respondents made heartfelt comments about their personal struggles and a sense of abandonment by a system they perceived to have taken their money and provided little in return. There is no doubt that the ORE is an expensive undertaking, however, the emphasis on quality means that it is a costly examination to develop and to deliver. The control of costs is a key consideration in the tendering process for supply of the examination.

If accurate, reports of registrants being coerced into poorly paid work, unpaid work and being subjected to poor employment practices in general dental practice settings is undoubtedly a matter of concern. It should be noted that this study did not seek to collect information from a comparative group of UK graduates. It is possible that some of these graduates also face similar challenges finding a satisfactory first job as an associate. Indeed, Gamble,9 citing his own personal struggle to find satisfactory employment after qualifying in the UK, discusses the challenges recent graduates face seeking suitable employment in general dental practice. The difficulties highlighted in our survey may therefore not be specific to ORE-route registered dentists. This subject could be explored with future research.

The findings of this survey share common ground with research carried out by the British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (BAPIO) in 2015 (N. Shah, BAPIO, personal communication, January 2018). That survey gathered 222 responses from overseas dentists who had passed the examination. However, the study only reported the factors that impinged negatively on ORE registrants. What emerged from the results of our survey was that 70 ORE dentists (16% of those who answered the question about the barriers to finding a PLVE placement and gaining paid employment thereafter) encountered no difficulties navigating their way through the system, and for some it had even been a positive experience. While this does not minimise the impact on the lives of those who were less fortunate, there was evidence that some ORE dentists felt well supported. The majority of respondents approached the London and West Midlands deaneries for advice. The reasons for that are unclear but may have been simply because that was where they were living at the time, so those places were a local point of contact. Relocating to a different part of the country sometimes provided better opportunities, however, it is appreciated that this may be more difficult for those with young families.

While registration conveys professional recognition, it does not constitute a work permit or a guarantee of further training or employment. Nevertheless, many ORE registrants felt unfairly treated when compared with UK graduates, perceiving the latter to have the benefit of fully-funded foundation training places. Where there is a shortfall in those places, the perception was that UK graduates generally find themselves better supported. From the comments made, many ORE registrants seemed to be in a postcode lottery with variable support nationwide. Some were very positive about the help given by local deaneries, while others had a different experience and were less complimentary.

In response to suggestions that greater transparency is needed about what to expect once the examination has been passed, a great deal has already been achieved in recent years to highlight the challenges, with no attempt to 'sugar-coat' the message. Both the Royal College of Surgeons of England10 (RCS) and the Committee of Postgraduate Dental Deans and Directors11 (COPDEND) websites have a section devoted to PLVE. The NHS Health Education England website12 also makes it clear that registration with the regulatory authority does not give overseas dentists the right to work in the UK, and those seeking work in general practice undertaking NHS work will need to have their names on an NHS Performers List. The BDJ Jobs webpage13 also informs visitors to the site that the NHS places additional requirements on overseas registrants seeking work in primary care settings, and that these requirements and the underpinning regulations will vary in the four countries that make up the United Kingdom. The RCS10 and COPDEND11 websites both provide a link to a comprehensive 'competency assessment framework' document commissioned by COPDEND and written by Alison Bullock in 2010. This sets out the process by which experienced non-EEA dentists who have passed the ORE and are registered with the GDC may gain VT equivalence that will allow them to join a list of performers. Thus, it appears that there is already a great deal of information available to prospective ORE candidates. However, from the perspective of ORE-route registered dentists, there remains a lack of clarity about whom to approach for advice and where to go for support that goes beyond 'the theoretical'.

Conclusion

This survey report provides insight into the experiences of ORE dentists once they register with the GDC. Though direct comparisons cannot be made with the experiences of UK graduates, the study has nevertheless highlighted the difficulties many of this group face. As a result, multiple stakeholders including deaneries, post-graduate trainers, the GDC and the wider dental community are better informed about the challenges that exist for these registrants. Overseas-qualified dentists contemplating practice in the UK should undoubtedly make themselves aware of the requirements that must be met following successful completion of the ORE through the currently available sources of information. However, all individuals and organisations that influence the experience of ORE-route registrants should consider their role in advising and supporting these potential contributors to the UK dental workforce.

References

Bissell V, Chamberlain S, Davenport E, Dawson L, Jenkins S, Murphy R. The Overseas Registration Examination of the General Dental Council. Br Dent J 2016; 221: 257-261.

Tan R T, Burke F J T. Response rates to questionnaires mailed to dentists. A review of 77 publications. Int Dent J 1997; 47: 349-354.

Kalsi A S, Kochlar S, Lewis N J, Haemmings K W. New graduates' knowledge of training and service provision within restorative dentistry: a survey. Br Dent J 2017; 222: 881-887.

Krosnick J A. Survey research. Annu Rev Psychol 1999; 50: 537-567.

British Dental Association. The State of General Dental Practice in 2013. 2013. Available at https://bda.org/dentists/policy-campaigns/campaigns/Documents/ddrb/state_of_general_dental_practice_november_2013.pdf (accessed February 2019).

Farmer E, van Rooij J, Riemersma J, Moraal J, Jorna P. Handbook of simulator-based training. Abingdon: Routledge, 1999.

Driskell J E, Willis R P, Copper C. The effect of overlearning on retention. J Appl Psychol 1992; 77: 615-622.

Sawyer T, White M, Zaveri P et al. Learn, see, practice, prove, do, maintain: an evidence-based pedagogical framework for procedural skills training in medicine. Acad Med 2015; 90: 1025-1033.

Gamble M A. Finding your first job as an associate in general dental practice. Br Dent J 2015; 218: 223-225.

Royal College of Surgeons. VT by Equivalence. Available at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/dental-faculties/fds/nacpde/vtbyequivalence/ (accessed February 2019).

COPDEND. Guidelines for British citizens with an EEA or Non-UK, Non-EEA, Overseas dental degree. 2017. Available at http://www.copdend.org/content.aspx?Group=eea&Page=eea_guidance (accessed February 2019).

NHS Health Careers. Information for overseas dentists. Available at https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/i-am/outside-uk/informationoverseasdentists (accessed February 2019).

BDJ Jobs. Working in UK dentistry from overseas. 2017. Available at https://www.bdjjobs.com/article/-workinginukdentistry (accessed February 2019).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the GDC for funding this survey, the GDC research team for help and advice, and lastly, the many ORE dentists who shared their thoughts and experiences with us.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jenkins, S., Bissell, V., Dawson, L. et al. What did they do next? A survey of dentists who have passed the Overseas Registration Examination of the General Dental Council. Br Dent J 226, 342–348 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0032-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0032-1

This article is cited by

-

COVID-19 self-isolation patterns in UK dental care professionals from February to April 2020

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Profiles of registrant dentists and policy directions from 2000 to 2020

BDJ Open (2020)