Abstract

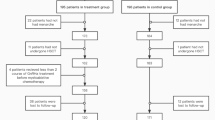

Serum concentrations of Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and Inhibin B were used to assess potential fertility in survivors of childhood haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) after three chemotherapy-conditioning regimens of differing intensity. Of 428 patients transplanted between 1990–2012 for leukaemia and immunodeficiency 121 surviving >1 year after a single HSCT were recruited. Group A had a treosulfan-based regimen (low-toxicity); Group B had fludarabine/melphalan (Flu-Mel) (reduced-intensity) and Group C had busulphan/cyclophosphamide (Bu-Cy) (myelo-ablative). Mean age at HSCT and follow-up and length of follow-up were 3.6, 11.8 and 9.9 years. Mean AMH standard deviation scores (SDS) were significantly higher in Group A (−1.047) and Group B (−1.255) than Group C (−1.543), suggesting less ovarian reserve impairment after treosulfan and Flu-Mel than after Bu-Cy. Mean serum AMH concentration was significantly better with treosulfan (>1.0 μg/l) than with Flu-Mel or Bu-Cy. In males, mean Inhibin B SDS was significantly higher in Group A (−0.506) than in Group B (−2.53) and Group C (−1.23) with the Flu-Mel group suffering greatest impairment. In conclusion, a treosulfan-based regimen confers a more favourable outlook for gonadal reserve than Flu-Mel or Bu-Cy in both sexes. Higher values of Inhibin B after Bu-Cy than after Flu-Mel may reflect recovery over time.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

09 February 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-020-0914-5

References

Brennan BM, Shalet SM. Endocrine late effects after bone marrow transplant. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:58–66.

Leiper AD. Non-endocrine late complications of bone marrow transplantation in childhood: part I. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:3–22.

Leiper AD. Non-endocrine late complications of bone marrow transplantation in childhood: part II. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:23–43.

Green DM, Kawashima T, Stovall M, Leisenring W, Sklar CA, Mertens AC, et al. Fertility of male survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:332–9.

Green DM, Kawashima T, Stovall M, Leisenring W, Sklar CA, Mertens AC, et al. Fertility of female survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2677–85.

Sklar CA, Mertens AC, Mitby P, Whitton J, Stovall M, Kasper C, et al. Premature menopause in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:890–6.

Grigg AP, McLachlan R, Zaja J, Szer J. Reproductive status in long-term bone marrow transplant survivors receiving busulfan-cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg). Bone Marrow Transpl. 2000;26:1089–95.

Sanders JE, Hawley J, Levy W, Gooley T, Buckner CD, Deeg HJ, et al. Pregnancies following high-dose cyclophosphamide with or without high-dose busulfan or total-body irradiation and bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1996;87:3045–52.

Teinturier C, Hartmann O, Valteau-Couanet D, Benhamou E, Bougneres PF. Ovarian function after autologous bone marrow transplantation in childhood: high-dose busulfan is a major cause of ovarian failure. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1998;22:989–94.

Michel G, Socié G, Gebhard F, Bernaudin F, Thuret I, Vannier JP, et al. Late effects of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for children with acute myeloblastic leukemia in first complete remission: the impact of conditioning regimen without total-body irradiation - a report from the Société Française de Greffe de Moelle. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2238–46.

Thibaud E, Rodriguez-Macias K, Trivin C, Espérou H, Michon J, Brauner R. Ovarian function after bone marrow transplantation during childhood. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1998;21:287–90.

Afify Z, Shaw PJ, Clavano-Harding A, Cowell CT. Growth and endocrine function in children with acute myeloid leukaemia after bone marrow transplantation using busulfan/cyclophosphamide. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2000;25:1087–92.

Laporte S, Couto-Silva AC, Trabado S, Lemaire P, Brailly-Tabard S, Espérou H, et al. Inhibin B and anti-Müllerian hormone as markers of gonadal function after hematopoietic cell transplantation during childhood. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:20.

Borgmann-Staudt A, Rendtorff R, Reinmuth S, Hohmann C, Keil T, Schuster FR, et al. Fertility after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in childhood and adolescence. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2012;47:271–6.

Bresters D, Emons JA, Nuri N, Ball LM, Kollen WJ, Hannema SE, et al. Ovarian insufficiency and pubertal development after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in childhood. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:2048–53.

Rao K, Amrolia PJ, Jones A, Cale CM, Naik P, King D, et al. Improved survival after unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation in children with primary immunodeficiency using a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen. Blood. 2005;105:879–85.

Chiesa R, Veys P. Reduced-intensity conditioning for allogeneic stem cell transplant in primary immune deficiencies. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8:255–66.

Shimizu M, Sawada A, Yamada K, Kondo O, Koyama-Sato M, Shimizu S, et al. Encouraging results of preserving ovarian function after allo-HSCT with RIC. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2012;47:141–2.

Papageorgiou SG, Ahmed O, Narvekar N, Davies M, Kottaridis PD. Preservation of fertility in women undergoing reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic transplantation with a fludarabine-based regime. Transplantation. 2012;94:e29–30.

Singhal S, Powles R, Treleaven J, Horton C, Swansbury GJ, Mehta J. Melphalan alone prior to allogeneic bone marrow transplantation from HLA-identical sibling donors for hematologic malignancies: alloengraftment with potential preservation of fertility in women. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1996;18:1049–55.

Jackson GH, Wood A, Taylor PR, Lennard AL, Lucraft H, Heppleston A, et al. Early high dose chemotherapy intensification with autologous bone marrow transplantation in lymphoma associated with retention of fertility and normal pregnancies in females. Scotland and Newcastle Lymphoma Group, UK. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;28:127–32.

Panasiuk A, Nussey SS, Veys P, Amrolia P, Rao K, Krawczuk-Rybak M, et al. Gonadal function and fertility after stem cell transplantation in childhood: comparison of a reduced intensity conditioning regimen containing melphalan with a myeloablative regimen containing busulfan. Br J Haematol. 2015;170:719–26.

Madden LM, Hayashi RJ, Chan KW, Pulsipher MA, Douglas D, Hale GA, et al. Long-term follow-up after reduced-intensity conditioning and stem cell transplantation for childhood nonmalignant disorders. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2016;22:1467–72.

Fujino H, Ishida H, Iguchi A, Onuma M, Kato K, Shimizu M, et al. High rates of ovarian function preservation after hematopoietic cell transplantation with melphalan-based reduced intensity conditioning for pediatric acute leukemia: an analysis from the Japan Association of Childhood Leukemia Study (JACLS). Int J Hematol. 2019;109:578–83.

ten Brink MH, Zwaveling J, Swen JJ, Bredius RG, Lankester AC, Guchelaar HJ. Personalized busulfan and treosulfan conditioning for pediatric stem cell transplantation: the role of pharmacogenetics and pharmacokinetics. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:1572–86.

Slatter MA, Rao K, Abd Hamid IJ, Flood T, Abinun M, Hambleton S, et al. Treosulfan and fludarabine conditioning for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with primary immunodeficiency: UK experience. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2018;24:529–36.

Levi M, Stemmer SM, Stein J, Shalgi R, Ben-Aharon I. Treosulfan induces distinctive gonadal toxicity compared with busulfan. Oncotarget. 2018;9:19317–27.

Greystoke B, Bonanomi S, Carr TF, Gharib M, Khalid T, Coussons M, et al. Treosulfan-containing regimens achieve high rates of engraftment associated with low transplant morbidity and mortality in children with non-malignant disease and significant co-morbidities. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:257–62.

Slatter MA, Rao K, Amrolia P, Flood T, Abinun M, Hambleton S, et al. Treosulfan-based conditioning regimens for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with primary immunodeficiency: United Kingdom experience. Blood. 2011;117:4367–75.

Slatter MA, Boztug H, Pötschger U, Sykora KW, Lankester A, Yaniv I, et al. Treosulfan-based conditioning regimens for allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with non-malignant diseases. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2015;50:1536–41.

Faraci M, Diesch T, Labopin M, Dalissier A, Lankester A, Gennery A, et al. Gonadal function after busulfan compared with treosulfan in children and adolescents undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2019;25:1786–91.

Anderson RA. What does anti-Müllerian hormone tell you about ovarian function? Clin Endocrinol. 2012;77:652–5.

Broer SL, Broekmans FJ, Laven JS, Fauser BC. Anti-Müllerian hormone: ovarian reserve testing and its potential clinical implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:688–701.

Kelsey TW, Wright P, Nelson SM, Anderson RA, Wallace WH. A validated model of serum anti-müllerian hormone from conception to menopause. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22024. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022024.

Lie Fong S, Visser JA, Welt CK, de Rijke YB, Eijkemans MJ, Broekmans FJ, et al. Serum anti-müllerian hormone levels in healthy females: a nomogram ranging from infancy to adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4650–5.

Brougham MF, Crofton PM, Johnson EJ, Evans N, Anderson RA, Wallace WH. Anti-Müllerian hormone is a marker of gonadotoxicity in pre- and postpubertal girls treated for cancer: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2059–67.

George SA, Williamson Lewis R, Schirmer DA, Effinger KE, Spencer JB, Mertens AC, et al. Early detection of ovarian dysfunction by anti-mullerian hormone in adolescent and young adult-aged survivors of childhood cancer. J Adolesc Young- Adult Oncol. 2019;8:18–25.

Pierik FH, Vreeburg JT, Stijnen T, De Jong FH, Weber RF. Serum inhibin B as a marker of spermatogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3110–4.

Crofton PM, Thomson AB, Evans AE, Groome NP, Bath LE, Kelnar CJ, et al. Is inhibin B a potential marker of gonadotoxicity in prepubertal children treated for cancer? Clin Endocrinol. 2003;58:296–301.

Chada M, Průsa R, Bronský J, Kotaska K, Sídlová K, Pechová M, et al. Inhibin B, follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone and testosterone during childhood and puberty in males: changes in serum concentrations in relation to age and stage of puberty. Physiol Res. 2003;52:45–51.

van der Kooi ALF, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, van den Berg SAA, van Dorp W, Pluijm SMF, Laven JSE. Changes in anti-müllerian hormone and inhibin B in children treated for cancer. J Adolesc Young- Adult Oncol. 2019;8:281–90.

van Beek RD, Smit M, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, de Jong FH, Hakvoort-Cammel FG, van den Bos C, et al. Inhibin B is superior to FSH as a serum marker for spermatogenesis in men treated for Hodgkin’s lymphoma with chemotherapy during childhood. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:3215–22.

van Casteren NJ, van der Linden GH, Hakvoort-Cammel FG, Hählen K, Dohle GR, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Effect of childhood cancer treatment on fertility markers in adult male long-term survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:108–12.

Crofton PM, Evans AE, Groome NP, Taylor MR, Holland CV, Kelnar CJ. Inhibin B in boys from birth to adulthood: relationship with age, pubertal stage, FSH and testosterone. Clin Endocrinol. 2002;56:215–21.

van Beek RD, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Laven JS, de Jong FH, Themmen AP, Hakvoort-Cammel FG, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone is a sensitive serum marker for gonadal function in women treated for Hodgkin’s lymphoma during childhood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3869–74.

Krawczuk-Rybak M, Leszczynska E, Poznanska M, Zelazowska-Rutkowska B, Wysocka J. Anti-müllerian hormone as a sensitive marker of ovarian function in young cancer survivors. Int J Endocrinol 2013;2013:125080

Miyoshi Y, Ohta H, Namba N, Tachibana M, Miyamura T, Miyashita E, et al. Low serum concentrations of anti-Müllerian hormone are common in 53 female childhood cancer survivors. Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;79:17–21.

Lunsford AJ, Whelan K, McCormick K, McLaren JF. Anti-müllerian hormone as a measure of reproductive function in female childhood cancer survivors. Fert Steril. 2014;101:227–31.

Charpentier AM, Chong AL, Gingras-Hill G, Ahmed S, Cigsar C, Gupta AA, et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone screening to assess ovarian reserve among female survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:548–54.

Hann IM, Stevens RF, Goldstone AH, Rees JK, Wheatley K, Gray RG, et al. Randomized comparison of DAT versus ADE as induction chemotherapy in children and younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Results of the Medical Research Council’s 10th AML trial (MRC AML10). Adult and Childhood Leukaemia Working Parties of the Medical Research Council. Blood. 1997;89:2311–8.

Gibson BE, Webb DK, Howman AJ, De Graaf SS, Harrison CJ, Wheatley K, United Kingdom Childhood Leukaemia Working Group and the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group. Results of a randomized trial in children with Acute Myeloid Leukaemia: medical research council AML12 trial. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:366–76.

Bergsten E, Horne A, Aricó M, Astigarraga I, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, et al. Confirmed efficacy of etoposide and dexamethasone in HLH treatment: long-term results of the cooperative HLH-2004 study. Blood. 2017;130:2728–38.

Andersson AM, Petersen JH, Jørgensen N, Jensen TK, Skakkebaek NE. Serum inhibin B and follicle-stimulating hormone levels as tools in the evaluation of infertile men: significance of adequate reference values from proven fertile men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2873–9.

Wigny KM, van Dorp W, van der Kooi AL, de Rijke YB, de Vries AC, Smit M, et al. Gonadal function in boys with newly diagnosed cancer before the start of treatment. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2613–8.

Mörse H, Elfving M, Lindgren A, Wölner-Hanssen P, Andersen CY, Øra I. Acute onset of ovarian dysfunction in young females after start of cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:676–81.

van Dorp W, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, de Vries AC, Pluijm SM, Visser JA, Pieters R, et al. Decreased serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels in girls with newly diagnosed cancer. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:337–42.

Lie Fong S, Laven JS, Hakvoort-Cammel FG, Schipper I, Visser JA, Themmen AP, et al. Assessment of ovarian reserve in adult childhood cancer survivors using anti-Müllerian hormone. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:982–90.

Thomas-Teinturier C, Allodji RS, Svetlova E, Frey MA, Oberlin O, Millischer AE, et al. Ovarian reserve after treatment with alkylating agents during childhood. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:1437–46.

van den Berg MH, Overbeek A, Lambalk CB, Kaspers GJL, Bresters D, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, et al. Long-term effects of childhood cancer treatment on hormonal and ultrasound markers of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1474–88.

Miyoshi Y, Yasuda K, Tachibana M, Yoshida H, Miyashita E, Miyamura T, et al. Longitudinal observation of serum anti-Müllerian hormone in three girls after cancer treatment. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. 2016;25:119–26.

Jadoul P, Anckaert E, Dewandeleer A, Steffens M, Dolmans MM, Vermylen C, et al. Clinical and biologic evaluation of ovarian function in women treated by bone marrow transplantation for various indications during childhood or adolescence. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:126–33.

La Marca A, Giulini S, Tirelli A, Bertucci E, Marsella T, Xella S, et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone measurement on any day of the menstrual cycle strongly predicts ovarian response in assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:766–71.

La Marca A, Grisendi V, Giulini S, Sighinolfi G, Tirelli A, Argento C, et al. Live birth rates in the different combinations of the Bologna criteria poor ovarian responders: a validation study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:931–7.

Nelson SM, Yates RW, Lyall H, Jamieson M, Traynor I, Gaudoin M, et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone-based approach to controlled ovarian stimulation for assisted conception. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:867–75.

La Marca A, Sighinolfi G, Radi D, Argento C, Baraldi E, Artenisio AC, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technology (ART). Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:113–30.

van Rooij IA, Tonkelaar ID, Broekmans FJ, Looman CW, Scheffer GJ, de Jong FH, et al. Anti-müllerian hormone is a promising predictor for the occurrence of the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2004;11:601–6.

Sowers MR, Eyvazzadeh AD, McConnell D, Yosef M, Jannausch ML, Zhang D, et al. Anti-mullerian hormone and inhibin B in the definition of ovarian aging and the menopause transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3478–83.

van den Berg MH, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Overbeek A, Twisk JW, Schats R, van Leeuwen FE, et al. Comparison of ovarian function markers in users of hormonal contraceptives during the hormone-free interval and subsequent natural early follicular phases. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1520–7.

Hamre H, Kiserud CE, Ruud E, Thorsby PM, Fosså SD. Gonadal function and parenthood 20 years after treatment for childhood lymphoma: a cross-sectional study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:271–7.

Dillon KE, Sammel MD, Ginsberg JP, Lechtenberg L, Prewitt M, Gracia CR. Pregnancy after cancer: results from a prospective cohort study of cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:2001–6.

van Dorp W, van der Geest IM, Laven JS, Hop WC, Neggers SJ, de Vries AC, et al. Gonadal function recovery in very long-term male survivors of childhood cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1280–6.

Rovó A, Tichelli A, Passweg JR, Heim D, Meyer-Monard S, Holzgreve W, et al. Spermatogenesis in long-term survivors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is associated with age, time interval since transplantation, and apparently absence of chronic GvHD. Blood. 2006;108:1100–5.

Anserini P, Chiodi S, Spinelli S, Costa M, Conte N, Copello F, et al. Semen analysis following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Additional data Evid-based counselling Bone Marrow Transpl. 2002;30:447–51.

Pfitzer C, Orawa H, Balcerek M, Langer T, Dirksen U, Keslova P, et al. Dynamics of fertility impairment and recovery after allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in childhood and adolescence: results from a longitudinal study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141:135–42.

Liesner RJ, Leiper AD, Hann IM, Chessells JM. Late effects of intensive treatment for acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia in childhood. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:916–24.

Molgaard-Hansen L, Skou AS, Juul A, Glosli H, Jahnukainen K, Jarfelt M, et al. Pubertal development and fertility in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia treated with chemotherapy only: a NOPHO-AML study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1988–95.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Great Ormond Street Hospital Childrens’ Charity (GOSHCC) who funded Dr Alison Leiper on a research grant, to make this research possible. Also thanks to Professor Yolanda de Rijke, head of the department of clinical chemistry, Erasmus MC, Netherlands and to Dr Helen Aitkenhead heading the clinical chemistry laboratory at GOSH, London, UK for ensuring the timely assay of AMH and Inhibin B samples. This work is supported by a grant (W1091) from the Great Ormond Street Hospital Childrens’ Charity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 14/WA/0115).

Informed consent

Patients were identified from the HSCT database and informed written consent obtained from all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leiper, A., Houwing, M., Davies, E.G. et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone and Inhibin B after stem cell transplant in childhood: a comparison of myeloablative, reduced intensity and treosulfan-based chemotherapy regimens. Bone Marrow Transplant 55, 1985–1995 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-020-0866-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-020-0866-9

This article is cited by

-

Treosulfan vs busulfan conditioning for allogeneic bmt in children with nonmalignant disease: a randomized phase 2 trial

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2024)

-

Allogeneic HSCT for Symptomatic Female X-linked Chronic Granulomatous Disease Carriers

Journal of Clinical Immunology (2023)

-

Recommendations on hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with Diamond–Blackfan anemia. On behalf of the Pediatric Diseases and Severe Aplastic Anemia Working Parties of the EBMT

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2021)

-

EBMT/ESID inborn errors working party guidelines for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for inborn errors of immunity

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2021)