Abstract

This study investigates the longitudinal association between living arrangements and psychiatrists’ diagnosis of depression in the general population. In 1990, 1254 Japanese men and women aged 40–59 years were enroled and completed questionnaires on the living arrangement in the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study (JPHC Study) and participated in a mental health screening (2014–2015). The study diagnosed a major depressive disorder (MDD) assessed by well-trained certified psychiatrists through medical examinations. During the follow-up, a total of 105 participants (36 men and 69 women) aged 64–84 years were diagnosed with MDD by psychiatrists. Living with a child (ren) was associated with a reduced risk of MDD for men but not for women; the respective multivariable ORs (95% CIs) were 0.42 (0.19–0.96) and 0.59 (0.32–1.09). These associations remained unchanged after adjusting for living with spouse and parent(s). In conclusion, living with a child (ren) was associated with a reduced risk of MDD in men, suggesting the role of a child (ren) in the prevention of MDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental health problems, particularly depression, are already known as serious public health issues. According to WHO reports, depression has emerged as the third leading cause of the global burden of disease in 2004 and is expected to become the first by 2030 [1]. Japan is not an exception [2]. A study reported that the economic burden of depression was approximately $11 billion, with $1570 million relating to direct medical costs, and $2542 million relating to depression-related suicide costs in Japan [3].

There are many potential risk factors for depression. Among them, living arrangements have attracted scientific interest [4, 5] because many countries have undergone rapid demographic changes [6]. The decline in marriage and birth rates has substantially changed living arrangements [6, 7]. These situations are particularly remarkable in Japanese society [7,8,9].

Previous studies have examined the association between living arrangements and psychological health [10,11,12,–13]. Almost all studies regarding depression were performed in Western countries to examine the association with living arrangements (living alone or not) [10]. Many previous studies in non-Western countries such as China, Singapore, and Thailand used a cross-sectional design or a longitudinal design, but the follow-up duration was as short as one year [14,15,16,–17]. Most studies using a self-report questionnaire used depressive symptoms as an outcome.

We used the data from a large nationwide cohort study with over a 20-year follow-up with certified psychiatrists’ diagnosis of MDD [18,19,–20] to investigate the association between the living arrangement of living with a spouse, child(ren), and parent(s) and the risk of MDD among Japanese men and women.

Methods

Study population

Participants of the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study (JPHC study) in 2014–2015, living in the Saku Public Health Center catchment area in Nagano prefecture, were invited for a mental health survey. The JPHC Study was launched at five public health centres (PHCs) in Japan for Cohort I in 1990 [18]. A self-administered questionnaire on demographic information, lifestyle characteristics, and social factors was distributed to uninstitutionalised residents aged 40–59 years in 1990 and follow-ups of 5 years, ten years, and 15 years after the first survey (response rates: 74–81%) were conducted.

There were 12,219 participants (6172 men and 6047 women) in the baseline survey. After excluding 3392 participants as they moved out of the study area, died, or did not respond to the latter questionnaires during follow-up, we selected the remaining 8827 persons. We invited participants to participate in a mental health survey. A total of 1299 out of 8827 participants (14.7%) responded to the mental health screening. We further excluded 21 participants due to incomplete data for the questionnaires relating to family configuration and 24 participants with a history of depression in the mental health screening questionnaires. The remaining 1254 participants (529 men and 725 women) aged 64–84 were included in the analysis. A flow diagram of the study participants is shown in Fig. 1.

Assessment of living arrangement

The question about the individual’s family configuration in the baseline questionnaire was, “Are you living with someone (spouse, child (ren), parent(s), others, alone) together now?” According to the Japanese culture, “others” are regarded as other family members; siblings, grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins, in-laws, etc. The same question was repeated for each follow-up survey. In the present study, we used a questionnaire of 1990, and only 15 persons (five men and ten women) living alone participated; hence, we could not analyse them as explanatory variables.

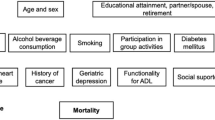

Covariates

Regarding past histories, we followed up the participants from 1990 until the screening in 2014–2015 and registered participants’ conditions, including survival and medical status, within the catchment areas of Saku City. We assessed the incidence of cancer using medical records from each hospital in the study area. We interviewed past histories of depression, diabetes mellitus, stroke, and myocardial infarction by self-administrated questionnaire of this mental health survey. All other covariates, except for past histories (smoking status, alcohol frequency, sleeping duration, and occupation), were questioned through the baseline survey in 1990.

Confirmation of depression

Certified psychiatrists assessed all participants in this mental health screening. First, we administrated the Center for Epidemiological Scale-Depression (CES-D) [21, 22] and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [23, 24] screening tests at the same time. Second, well-trained board-certified psychiatrists interviewed the participants by referring to the CES-D and PHQ-9 scores. Finally, the psychiatrists assessed whether the participant was diagnosed with MDD based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria [19, 20] and reached a consensus for final diagnosis when each psychiatrist’s diagnosis was different.

If a patient experiences depressive symptoms, they are not always diagnosed with depression [25]. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), dementia, and pseudodementia may be associated with similar symptoms [25,26,–27]. It is often difficult for general doctors to distinguish MDD from others, and patients sometimes have overlapping diseases [25, 28]. Well-trained board-certified psychiatrists met the 1299 participants, confirmed their self-report questionnaires, and assessed whether the participants currently met the DSM-IV criteria for MDD after considering whether their depressive symptoms caused clinically significant distress or impairment [19].

Statistical analysis

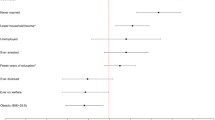

Logistic regression analyses were performed to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of MDD associated with the family configuration. We adjusted for age (years, continuous) and sex in the first model and adjusted for other lifestyle-related factors and health history in the second model. These factors included smoking status (never, former, current), alcohol frequency (seldom, 1–3 times per month, 1–2 times per week, 3–4 times per week, 5–6 times per week, every day), sleeping duration (≤4 h, 5–9 h, ≥10 h), occupation (professional, managerial, white-collar, and blue-collar jobs), and education (primary education, lower secondary education, upper secondary education, post-secondary education), history of cancer (yes or no), stroke (yes or no), myocardial infarction (yes or no), and diabetes mellitus (yes or no). The rate of missing values was lower than 0.2–1.4%. Missing data were assumed to be missing at random (MAR), and we used multiple imputations to handle missing data of confounding variables using the ‘mice’ package in R software. All variables in the dataset used in this study were included in the imputation model. Results across five imputed datasets were combined by averaging, and standard errors were adjusted to reflect both within-imputation variability and between-imputation variability in the pooling phase [29]. The level of statistical significance was set α = 0.05 (two-tailed). All statistical analyses were conducted by the R software (version 3.5.3; https://www.r-project.org/).

Results

The characteristics of study participants who had lived with a child (ren), a spouse, and a parent(s) at baseline are shown in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 47 years, and 58% were women. Except for age, no significant differences were found for any other characteristics. Among the 1254 participants (529 men and 725 women), 105 participants (36 men and 69 women) were diagnosed with MDD by board-certified psychiatrists.

Table 2 shows the odds ratios (ORs) of MDD according to living arrangements. Among the group living with a child (ren) or not, ORs (95% CI) of MDD were 0.42 (0.19 to 0.96) for men, 0.59 (0.32 to 1.09) for women and 0.53 (0.32 to 0.85) for total participants. When we tested our hypothesis of no association with Bonferroni correction in total participants, the P value was 0.012, which was under 0.0167(=0.05/3), rejecting the hypothesis. These associations remained unchanged after further adjustment for living with a spouse and living with parent(s).

Fifteen persons living alone participated in the present study. However, we found that the association between living with a child (ren) and the risk of MDD remained unchanged even after excluding participants living alone (Supplementary Table 1). We conducted another sensitivity analysis, dividing the group of ‘not living with a child(ren)’ into two groups of ‘not having a child(ren)’ and ‘having but not living with a child(ren)’ because the child(ren) of participants had already moved out from home at the baseline survey. Then, we examined the ORs of MDD in ‘having but not living with a child(ren)’ and ‘living with a child(ren)’ in reference to ‘not having a child(ren),’ and found that these two groups had a lower risk of MDD in total participants (Supplementary Table 2).

However, no significant associations were observed between living with a spouse, parent(s), and risk of MDD.

Discussion

In this prospective study of Japanese men and women aged 40–59 years, we found that living with a child (ren) was associated with a 62% lower risk of MDD after adjusting for potential confounding factors for men, and a weak and insignificant association was observed for women.

A cross-sectional study of 1561 parents aged ≥60 years in the Anhui Province, China, found that older adults living with three generations or living with grandchildren had a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms than those living in single-generation households [14]. Another cross-sectional analysis under the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) of 6001 men and women aged ≥60 years showed that older adults living with both a child and spouse or living alone were more likely to have depressive symptoms than those living only with a spouse (odds ratio = 1.23 [1.06–1.42] and 1.40 [1.03–1.92], respectively) [17]. These two studies showed the opposite effect of living with descendants. However, the cross-sectional design was liable to reverse causation because family members likely supported those who experienced depression episodes in their families [30].

Moreover, a 3-year follow-up of the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES) of 19,656 men and 22,513 women aged ≥65 years reported that living with a spouse and child for men was associated with increased odds of depressive symptoms (odds ratio = 1.19 [1.04–1.36]) In the 65–74 years group, but the odds reduced for women (odds ratio = 0.81 [0.71–0.94]) [10]. In the present study we found a strong association between living with a child (ren) and a reduced risk of MDD in men but not in women. This difference may be due to the different durations of follow-up and outcome estimation. While JAGES used depressive symptoms assessed by the self-report questionnaire, this study used a certified psychiatrist’s diagnosis.

The absence of a significant association between living with a spouse and the risk of MDD in the present study could be due to the small number of persons who did not live with their spouse. A cross-sectional study of 4685 Finnish men and women aged 30–64 years showed that persons living alone were more likely to have depressive disorders than persons living with spouses [13]; ORs (95% CI) of MDD were 1.62 (1.01–2.62) for men and 1.66 (1.12–2.45) for women. We found no association between living with parents and the risk of MDD. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the effect of living with parent(s) separately on the risk of MDD.

Almost all of the previous studies conducted in Western countries have not focused on who people live with but on whether people live alone or not [10]. A past systematic review of 74 community-based mental health surveys on depression reported that living alone was identified as a risk factor for depression in aged populations in the world including Europe, North America, South America, Australia, and Asia [31].

Living with a child (ren) may soothe men’s stress, probably because they can receive social and financial support. According to the Annual Report on Health, Labour and Welfare 2015–2016, the first leading cause of worry in old age among Japanese was a healthy life, and the second was finance [32]. More than 72 percent of Japanese aged ≥40 years wanted to stay in their own houses instead of the nursing home when they were older and tended to seek social support from their child(ren) [32]. More than 60 per cent of persons aged ≥70 years wanted to live with a child (ren) or nearby [32]. Additionally, 78 per cent of old-age households depend mainly on public pension income [33]. However, the population census in Japan has shown that the proportion of people living alone or residing with aging parents has increased for both middle-aged women and married couples since the 1970s [34].

An advantage of the present study is that we used long-term follow-up data instead of cross-sectional data. We could reduce the possibility of reverse causality, a limitation for most cross-sectional previous research. Another strength of this study is that we minimised the outcome measurement errors by the board-certified psychiatrists’ diagnosis, which is highly recommended [28].

Several limitations of our study warrant discussion. First, the statistical power was insufficient to examine the association, as the limited number of persons living alone enroled. Second, selection bias may have occurred because 14% of the eligible participants participated in this study. Last, there was residual or uncontrolled confounding for the association between living arrangements and risk of MDD such as household income, a family history of mental disease and depression/psychiatric status.

In conclusion, our study indicated that living with a child (ren) was associated with a reduced risk of MDD. Our results suggest that elderly persons may benefit by preventing MDD, possibly through social and financial support from children.

Data availability

For information on how to apply to gain access to JPHC data, follow the instructions at https://epi.ncc.go.jp/en/jphc/805/8155.html.

References

World Federation for Mental Health. DEPRESSION: A Global Crisis World Mental Health Day, October 10 2012: World Federation for Mental Health. 2012. Available at https://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/wfmh_paper_depression_wmhd_2012.pdf (Accessed 30 Jan 2021).

Naganuma Y, Tachimori H, Kawakami N, Takeshima T, Ono Y, Uda H, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in four areas in Japan: Findings from the World Mental Health Japan Survey 2002–2003. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:240–8.

Okumura Y, Higuchi T. Cost of depression among adults in Japan. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13:e1–9.

Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119–38.

Sarris J, O’Neil A, Coulson CE, Schweitzer I, Berk M. Lifestyle medicine for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:1–13.

Bongaarts J. Human population growth and the demographic transition. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2009;364:2985–90.

The Japanese National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. The 7th National Survey on Household Changes, 2014;2014.

Muramatsu N, Akiyama H. Japan: Super-aging society preparing for the future. Gerontologist. 2011;51:425–32.

The Japanese National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. The 6th Annual Population and Social Security Surveys, 2018;2018.

Honjo K, Tani Y, Saito M, Sasaki Y, Kondo K, Kawachi I, et al. Living alone or with others and depressive symptoms, and effect modification by residential social cohesion among older adults in Japan: The JAGES longitudinal study. J Epidemiol. 2018;28:315–22.

Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, McGinn MM. Recommended for how to write a search strategy - marital quality and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bull. 2015;140:140–87.

Russell D, Taylor J. Living alone and depressive symptoms: The influence of gender, physical disability, and social support among hispanic and non-hispanic older adults. J Gerontol - Ser B Psychological Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:95–104.

Joutsenniemi K, Martelin T, Martikainen P, Pirkola S, Koskinen S. Living arrangements and mental health in Finland. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:468–75.

Silverstein M, Cong Z, Li S. Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: consequences for psychological well-being. J Gerontol: Ser B. 2006;61:256–66.

Chan A, Malhotra C, Malhotra R, Østbye T. Living arrangements, social networks and depressive symptoms among older men and women in Singapore. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:630–9.

Abas M, Tangchonlatip K, Punpuing S, Jirapramukpitak T, Darawuttimaprakorn N, Prince M, et al. Migration of children and impact on depression in older parents in rural Thailand, Southeast Asia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:226–34.

Zhang Y, Liu Z, Zhang L, Zhu P, Wang X, Huang Y. Association of living arrangements with depressive symptoms among older adults in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1–10.

Tsugane S, Sawada N. The JPHC Study: design and some findings on the typical Japanese diet. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:777–82.

Matsuoka YJ, Sawada N, Mimura M, Shikimoto R, Nozaki S, Hamazaki K, et al. Dietary fish, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid consumption, and depression risk in Japan: a population-based prospective cohort study. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1242.

Okubo R, Matsuoka YJ, Sawada N, Mimura M, Kurotani K, Nozaki S, et al. Diet quality and depression risk in a Japanese population: the Japan Public Health Center (JPHC)-based Prospective Study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7150.

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychological Meas. 1977;1:385–401.

Shima S, Shikano T, Kitamura T, Asai MA. New self-report depression scale (in Japanese). Seishinigaku. 1985;27:717–23.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Muramatsu K, Miyaoka H, Kamijima K, Muramatsu Y, Yoshida M, Otsubo T, et al. The patient health questionnaire, Japanese version: validity according to the miniinternational neuropsychiatric interview-plus. Psychol Rep. 2007;101:952–60.

Lamberty GJ, Bieliauskas LA. Distinguishing between depression and dementia in the elderly: a review of neuropsychological findings. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1993;8:149–70.

Gagliardi JP. Differentiating among depression, delirium, and dementia in elderly patients. Virtual Mentor. 2008;10:383–8.

Ismail Z, Elbayoumi H, Fischer CE, Hogan DB, Millikin CP, Schweizer T, et al. Prevalence of depression in patients with mild cognitive impairment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:58.

Cepoiu M, McCusker J, Cole MG, Sewitch M, Belzile E, Ciampi A. Recognition of depression by non-psychiatric physicians - a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:25–36.

Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation for interval estimation from simple random samples with ignorable nonresponse. J Am Stat Assoc. 1986;81:366–74.

Kramer EJ, Kwong K, Lee E, Chung H. Culture and Medicine Cultural factors influencing the mental. West J Med. 2002;176:227–31.

Barua A, Ghosh MK, Kar N, Basilio MA. Socio-demographic factors of geriatric depression. Indian J Psychol Med. 2010;32:87–92.

Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Annual Health, Labour and Welfare Report, 2016;2016.

Japanese Public Relations Office of the Cabinet Office Public Opinion Survey on the Life planning of old age and Public pension, 2018;2019.

Statistics Bureau of Japan. The Population Census of Japan, 2015;2015. Available at https://www.scb.s/okumentatio/lassifikationer-och-standarde/vensk-utbildningsnomenklatur-sun/. Accessed 24 Jan 2021.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all the support of group members in the Saku area, Keio University, for carrying the survey out and in the headquarter. We thank their enormous efforts to collect the data from baseline to follow-up survey of this study. The authors also appreciate every participant in this survey. The opinions showed in this paper are those of authors and do not necessarily correspond to the ones of the National Cancer Center, Japan.

Funding

The National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund, and the SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation supported this study. There is no involvement of funding agency in the design of this study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, manuscript, and the progression to publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

KO, KS, and HI contributed to the conception. KO, KS, NS, MM and HI contributed to the design. SN, RS, NS, MM, HI and ST contributed to data acquisition and pre-processing. KO, KS, and HI contributed to data-analysis. KO drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in revising it critically for important intellectual content. We sincerely thank the participants in Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study Group for their ongoing participation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Boards of the National Cancer Centre of Japan, Osaka University, and the Keio University School of Medicine approved this study. We conducted this research according to the protocol and the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) statement [35]. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. The protocol of this study was approved by the ethical review board of Osaka University, Osaka, Japan. Since the registry data were already anonymous, the review board waived informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogawa, K., Shirai, K., Nozaki, S. et al. The association between midlife living arrangement and psychiatrist-diagnosed depression in later life: who among your family members reduces the risk of depression?. Transl Psychiatry 12, 156 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-01880-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-01880-7