Abstract

The Research Domain Criteria project (RDoc) proposes a new classification system based on information from several fields in order to encourage translational perspectives. Nevertheless, integrating genetic markers into this classification has remained difficult because of the lack of powerful associations between targeted genes and RDoC domains. We hypothesized that genetic diseases with psychiatric manifestations would be good models for RDoC gene investigations and would thereby extend the translational approach to involve targeted gene pathways. To explore this possibility, we reviewed the current knowledge on Prader–Willi syndrome, a genetic disorder caused by the absence of expression of some of the genes of the chromosome 15q11–13 region inherited from the father. Indeed, we found that the associations between genes of the PW locus and the modification identified in the relevant behavioral, physiological, and brain imaging studies followed the structure of the RDoC matrix and its six domains (positive valence, negative valence, social processing, cognitive systems, arousal/regulatory systems, and sensorimotor systems).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The current diagnostic systems in psychiatry, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), were developed to provide a common language to define psychiatric disorders. These systems improved psychiatric diagnosis by specifying symptom clusters and offering standardized categorization across the world. Nevertheless, this diagnostic approach is based only on symptoms and thus presents some limitations, especially for a pathophysiological approach. The inclusion of biomarkers was a request for the last edition of the DSM but this did not occur. Although the diagnostic categories have been built from clearly defined symptoms, they have continued to show considerable clinical heterogeneity, which has made it difficult to determine the significant biomarkers1. An alternative of the categorical approach is the dimensional approach. This approach was discussed deeply for the DSM-5, but it was finally not chosen. However it is considered particularly relevant for NeuroDevelopmental Disorder (NDD)2,3.

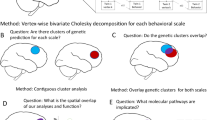

To address the need for a new approach to classifying mental disorders, the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) launched the Research Domain Criteria project (RDoC). The ultimate goal of this project is prediction medicine for psychiatry, which means a diagnostic system based on a deeper understanding of the biological and psychosocial bases of a group of disorders4. The current version of the RDoC matrix is constructed around six major domains: negative valence systems, positive valence systems, cognitive systems, systems for social processes, arousal/regulatory systems, and sensorimotor systems. The RDoC matrix is used to investigate circuit-based functional dimensions across multiple units of analysis (circuits, physiology, behavior, and self-reports) both synchronically and diachronically, this last through the neurodevelopmental dimension. In addition, the two additional aspects of neurodevelopmental trajectories and interactions with the environment are equally important elements of the RDoC framework.

Despite the clear relevance of gene investigations that include neurodevelopment and environmental interactions (epigenetic), the references to specific genes had to be removed from the RDoC matrix indeed psychiatric disorders are complex disorders and genetic variance (major gene and common variation) do not explain transmission as a whole5. Genetic investigations have thus continued to be a major challenge for psychiatric research. For this reason, we hypothesized that genetic disorders presenting psychiatric symptoms would provide valuable information to expand the RDoC matrix, especially by connecting the RDoC domains to well-identified mutations. Moreover, some genetic disorders can be diagnosed just after birth, offering the possibility of neurodevelopmental investigation.

Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS) is a rare genetic neurodevelopmental disorder resulting from a paternally inherited gene mutation, including the lack of expression of several imprinted genes of the chromosome 15 locus q11-q136 region (Fig. 1). At birth, PWS patients present hypotonia with impaired feeding behavior comprising sucking and swallowing deficits and anorexia, which lead to failure to thrive. Conversely, in childhood and adulthood, the patients display hyperphagia and poor satiety, which leads to early severe obesity with endocrine dysfunction (impaired sexual development and growth, central hypothyroidism) and intellectual disabilities. This syndrome is also associated with psychiatric manifestations, including symptoms that can be connected with several DSM and ICD diagnoses, such as intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders7, schizophrenic disorders8, addictive behaviors9,10, obsessive-compulsive disorders11, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and mood disorders12. Besides ID that is common, the heterogeneity in these potential ICD and DSM diagnoses indicates the limitations of these classifications, especially for comprehensive genetic models. The dimensional approach has, however, been supported by a rich literature for PWS that includes biological, neuroimaging, and behavioral characterizations of human disease combined with data from mice and cell models.

The diagnosis of PWS is currently made in the first months of life13 and the early follow-up of these patients has made it possible to describe the evolution in symptoms. This is especially the case for eating behavior, which generally shifts from anorexia in infancy to hyperphagia in childhood and adulthood following specific nutritional phases14. Moreover, therapeutic studies have observed the age-related effects—and therefore the neurodevelopmental steps (or phases)—on the therapeutic results, which have been well-documented in studies on the administration of intranasal oxytocin (OXT). The studies have revealed results that vary with the age at administration and have clearly identified an early biological window15,16.

Last, the clinical and pathophysiological research on PWS has paved the way for unraveling the functions of the candidate genes. Indeed, although the PWS chromosomal region encompasses several maternal imprinted genes, recent studies were able to connect some of them with specific symptoms and phenotypes. The lack of expression of the MAGEL2 gene causes Schaaf–Yang disease, which includes social interaction deficits with autism spectrum disorders and early feeding deficits17. SNORD116 is the minimal gene mutation associated with the PWS-like phenotype, including the shift from early anorexia to hyperphagia and social interaction impairments18,19.

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that the RDoC matrix would be a useful way to combine the data on the psychiatric manifestations of PWS and the genetic data on this disease, ultimately helping to identify new genetic markers to document the RDoC dimensions. To develop this point, we describe the current knowledge on PWS following the RDoC matrix structure.

RDoC approach and PWS

Positive valence

Positive valence systems include the response to positive motivational situations or contexts, such as reward seeking, consummatory behavior, and reward learning. They are composed of several constructs, such as reward responsiveness, reward learning, and reward valuation. PWS patients present an excessive response in the positive valence system for food.

Behavior

PWS patients display hyperphagia and food‐related behaviors that dramatically impair socialization and occupational performance, substantially deteriorate their quality of life and that of their relatives, and are responsible for significant morbidity and mortality especially linked to obesity development, complications, and gorging behavior10. Early diagnosis has led to better knowledge of the natural evolution of the disease and a description of the nutritional phases and eating behavior14. At birth, PWS newborns show poor appetite and sucking, with low weight gain and failure to thrive. Then, at about 2 years old, rapid and excessive weight gain precedes the manifestation of an excessive interest in food and a growing appetite, with ultimately the development of hyperphagia with poor satiety. The gradual rise in the focus on food and the continuing changes in appetite can be detected at ~4–5 years old, while independent food-seeking behaviors and visible hyperphagia becomes evident at 8–9 years. In the absence of proper care and management, early excessive weight gain followed by hyperphagia and impaired satiety results in severe obesity10. Moreover, the eating behavior presents specificities in reward control: that is, patients with PWS who are offered unlimited access to food will consume approximately three times more food and spend more time searching for and storing food than control subjects. The response to reward is also modified, as the preference for high-carbohydrate food is significantly higher in PWS patients than in obese patients. In addition, PWS patients are more likely to eat contaminated food and to make inappropriate food combinations than controls with and without intellectual disabilities.

Pathophysiology

The levels of ghrelin, and more generally the ghrelin system20, are abnormal in PWS. This gut peptide secreted by the stomach is the only orexigenic peptide. It is associated with eating behavior regulation, especially with the food craving, food hoarding and foraging, and food anticipatory activity that are displayed by patients with PWS, and it may be linked to the dopaminergic reward circuits. PWS patients display high circulating levels of ghrelin21 and this hyperghrelinemia starts early in life, before the occurrence of hyperphagia and obesity. Moreover, the circulating ghrelin levels in these patients remain elevated at all ages compared with age-matched controls and obese patients21. Modifications in the ratio of the two forms of ghrelin (acylated and unacylated) have been described in PWS. Acylated ghrelin (AG), considered the active form of the so-called “hunger hormone,” has orexigenic effects, and the unacylated (UAG) form has been reported to have the opposite effects. Infants with PWS have normal AG levels and high UAG levels, in contrast to later in life when they display obesity and hyperphagia. The relatively high UAG in infants may explain their poor appetite, which is comparable to anorexia22 and the high levels of AG with a relative deficit of UAG later on in life explain the hyperphagia and food craving. As a whole, total ghrelin levels are elevated in PWS at all ages.

Interestingly, the elevated total ghrelin levels with normal AG levels were also found in Magel2-knockout (KO) mice, which reproduce the postnatal anorexic phase observed in patients with PWS and show the same findings regarding circulating ghrelin20. In humans, MAGEL2 mutations cause Schaaf–Yang syndrome, a PWS‐like syndrome characterized by an early feeding deficit and hypotonia, in association with severe autistic features, hormonal deficits and a lower occurrence of obesity compared to PWS.

Moreover, Snord116 KO mice display an elevated ratio of proghrelin to mature ghrelin protein in stomach lysates. Of note, the antibodies used in conventional ghrelin assays detect both mature and unprocessed AG and UAG. However, the mice do not become obese, although display hyperphagia. Nevertheless, mediobasal hypothalamic deletion of Snord116 induced in adult animals, which necessarily bypasses the neonatal period, resulted in both frank hyperphagia and, in a subset of animals, frank obesity23. These data are consistent with observations in cell models deleted for SNORD116, which display low levels of the hypothalamic gene PSK1 encoding for the proconvertase PC1 enzyme, an endopeptidase responsible for the maturation of several hypothalamic and nonhypothalamic peptides, including ghrelin24. Thus, the reported hyperghrelinemia in patients with PWS and Snord116 KO mice models likely reflects elevated circulating proghrelin and ghrelin.

Circuits

Modifications in brain activation were found to be related to eating behaviors in PWS, with significantly greater BOLD activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in patients than controls when viewing food pictures25. In addition, these patients exhibit greater activation in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), medial prefrontal cortex (PFC), insula, hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus as they viewed the food pictures26. Compared with obese patients, PWS patients also demonstrate higher activity in reward/limbic regions (NAc, amygdala) and lower activity in the hypothalamus and hippocampus27. According to structural studies, PWS individuals show small gray matter volume in the OFC, a region that may be associated with both overeating and a propensity for detrimental food preferences, such as overindulgence in sweet foods. In addition, small gray matter volume is also noted in the caudate nucleus, a region that gives rise to disinhibition and a variety of affective disorders28.

Negative valence

Negative valence systems are responsible for responses to aversive situations or contexts, such as fear, loss, or anxiety. They are composed of several constructs: acute threat (fear), potential threat (anxiety), sustained threat, loss, and frustrative nonreward. In PWS patients, negative valence has been associated with changes in routines or expectations.

Behavior

The aversive nature of change in PWS might be associated with frustrative nonreward and it may cause specific behavior patterns (e.g., temper outbursts)29,30. PWS patients frequently display anxiety and anxious moods. Indeed generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety, and compulsive behaviors are more frequently diagnosed in PWS children than other children with intellectual disabilities6,31.

Pathophysiology

The genetic mutation of PWS encompasses the SNORD 115 gene responsible for changes in the edition and alternative splicing of the serotonin receptor 2 C (5-HT2cR)32,33. Moreover, one study reported abnormal serotonin turnover associated with PWS, with elevated concentrations of serotonin metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid of children and adolescents34.

5-HT2cR is implicated in the regulation of a variety of physiological functions, such as mood, satiety, and reproduction, and aberrant 5-HT2cR signaling might be associated with anxiety, depression, and obesity. People with PWS present features, close to obsessive-compulsive behavior, that can be explained by dysregulation of the serotonergic system, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are sometimes prescribed to ameliorate the symptoms35,36. Mice lacking expression of PWS locus genes exhibit alterations in specific 5-HT2cR-related behaviors along with increased RNA-editing of the 5ht2c pre-mRNA37. Moreover, mice with mutations of all the sites for edition of 5HT2c R display features comparable to PWS, including failure to thrive, decreased somatic growth, neonatal hypotonia, and reduced food consumption followed by postweaning hyperphagia38.

Circuits

PWS patients show small gray matter volume in the OFC that is linked to compulsive behavior28 and abnormal functional connectivity between the PFC and basal ganglia and within the subcortical structures that correlate with the presence and severity of obsessive-compulsive behaviors39.

Cognitive systems

Cognitive systems are responsible for several cognitive processes. They are composed of attention (referring to processes that regulate access to capacity-limited systems), perception (referring to processes that perform computations on sensory data), declarative memory (referring to the acquisition or encoding, storage and consolidation, and retrieval of representations of facts and events), and language and cognitive control (referring to a system that modulates the operation of other cognitive and emotional systems and is engaged in the case of novel contexts). Intellectual disability is classically described in PWS as involving several cognitive systems, although the intellectual quotient (IQ) also depends on the type of mutation, and PWS subjects with maternal disomy have significantly higher verbal IQ scores than those with a deletion40.

Behavior

Attentional skill is weakened in the PWS population for both global and selective attention41,42. Immediate memory is also affected, with low scores43. However, when the task requires simultaneous visual processing, the scores are preserved44,45. PWS patients display learning difficulties especially in observational learning46,47. A deficit in executive function has been observed with impaired mental switching30,48, and impaired inhibition capacities have also been noted49. Concerning visual perception, some authors have argued that patient with PWS display higher skills to detect similarities which possibly explain their high performance in puzzle processing45. However, more recent study noted greater deficits verbal or visual concerning the sequential processes42.

Pathophysiology

Currently, the biological markers in the model of cognitive impairment and behavior suggests the effect of the genetic status on brain development, with the assumption that a genetic abnormality will influence neurodevelopment30. Nevertheless, the biological pathway that has been impaired during neurodevelopment has yet to be specified.

Circuits

During neurodevelopment, several brain regions show impairment in PWS: the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes have lower local gyrification indices, and lower gyrification in the frontal lobes is correlated with lower IQ in children with PWS50.

Social processes

The social processes mediate responses in interpersonal settings of various types and include the perception and interpretation of the actions and thoughts of others. These processes are composed of constructs of affiliation and attachment, social communication and perception, and understanding of self. PWS patients show deficits in emotion recognition, expression, and regulation and in social behaviors. The ability to establish appropriate social interactions entails several distinct processes. First, the social agent must recognize the others as “living persons,” then she/he has to recognize the other behaviors in terms of mental states and dispositions (i.e., “mentalizing” or “theory of mind”, finally she/he has to modulate the decision-making of her/his behavior. The outcome of these processes will likely lead the observer to adapt her/his own social behavior. The impairment in social interaction could impact one of several of these steps. Various tests have been developed to precisely identify the deficits in social skills such as Sally et Ann test and proposed scoring systems.

Behavior

PWS patients recognized joy in 90% of the cases presented to them but sadness in only 55%, anger in 40%, fear in 37%, surprise in 55%, and disgust in 43%51. These patients have an impaired ability to organize visual information into a coherent social story, have more difficulty making appropriate social attributions than do other patients matched for IQ52, and show impaired voice detection and face53,54,55. Moreover, PWS patients fare worse than Down’s syndrome patients in behavior with others and are less active in social organization56 in association with emotional lability57,58.

Pathophysiology

Event-related potential (ERP) research has shown that PWS patients demonstrate altered processing of, attention to and/or recognition of faces and their expressions59. In PWS, the pathophysiology underlying social withdrawal has been attributed to impaired and dysfunctional hypothalamic OXT neurons57,60, and studies have shown improvements in PWS patients after intranasal OXT administration15,16. MAGEL2 KO mice, which also show impaired eating behavior at birth and social impairment close to autism, are likewise improved by postnatal intranasal OXT treatment. In the MAGEL2 mice model, defects in OXT secretion, receptors and neurons have now been clearly established. In addition, the inactivation of Magel2 suppresses OXT neuron activity through an altered synaptic input profile, with reduced excitatory and increased inhibitory currents61. Last, hypothalamic neurons derived from induced pluripotent cells (IPSCs) deleted for SNORD116 display a dysfunction in OXT synthesis with a defect in OXT maturation24.

Circuits

PET scans of PWS patients have revealed a hypoperfusion in the anterior gyrus cinguli and the superior part of the temporal lobes, two regions implicated in theory of mind and empathy62. In addition, these patients show small gray‐matter volume in the OFC. In this brain region, two distinct populations of neurons were identified in mice, one related to feeding and the other to social response. This naturally feeding-responsive neuron population was causally linked to increased feeding behavior and the naturally social-responsive neuron population, which inhibits feeding, thereby indicating an association between social processes and eating behaviors63.

Arousal/ regulatory systems

The arousal/regulatory systems are responsible for activating neural systems for various systems, as appropriate, and providing homeostatic regulation. They are composed of constructs of arousal, circadian rhythms, sleep, and wakefulness. PWS patients present sleep disorders and arousal dysregulation.

Behavior

PWS patients display sleep abnormalities with central sleep apnea predominating in infants and children64 and excessive daytime sleepiness with or without narcolepsy. Moreover, some patients continue to have difficulty with hypersomnia even after the sleep apnea has been treated, and the excessive sleepiness seems to be due to hypothalamic dysfunction65,66. In others, the sleep disorder is associated with a narcolepsy-like phenotype that includes sleep-onset REM periods and sometimes cataplexy67. PWS patients also show endocrine dysfunction with pituitary hormone deficits, which explains the growth retardation, hypogonadism, and metabolic and appetite dysregulation.

Pathophysiology

The sleep-wake cycle is regulated by two major processes: homeostatic sleep pressure, which is defined as the gradual accumulation of sleep factors (i.e., peptides, hormones, and neurotransmitters), and circadian rhythms, which can be linked to the feedback loop of the core time-keeping genes: Per, Cry, CLOCK, and BMAL1 and their target genes. These genes in turn mediate circadian timing in physiological processes, such as sleep, feeding, and energy balance68. In PWS, the lack of expression of MAGEL2 and SNORD116 has been noted to be associated with a shortened circadian rhythm and dysregulation of diurnally regulated gene expression, as well as with a further dysregulation of sleep and activity69,70,71. Moreover, orexin-A (hypocretin-1), a neuropeptide crucial for maintaining wakefulness, has shown an intermediate level in the cerebral spinal fluid of some PWS patients with excessive daytime sleepiness72,73.

Concerning homeostasis, mice deleted for Snord116 display an increased energy expenditure, likely via the Neuropeptide Y (NPY) system in the hypothalamus74, the upregulation of AGRP, and the downregulation of Proopiomelanocortin (POMC)19,75 The lack of expression of Magel2 in mice leads to dysregulation of leptin sensitivity in the POMC neurons, which thus fail to induce the fasting response76.

Sensorimotor systems

The sensorimotor systems are primarily responsible for the control and execution of motor behaviors and their refinement during learning and development. They are composed of constructs for motor actions, agency and ownership, habits, and innate motor patterns. Sensory processing involves perceiving, organizing and interpreting information received through sensory systems (e.g., touch, smell, sight, auditory, taste, and vestibular) in order to produce an adaptive response. The term “sensory integration” refers to the ability to produce appropriate motor and behavioral responses to stimuli. PWS is characterized by motor and sensory impairment.

Behavior

PWS is characterized by motor system modifications with severe hypotonia in infancy. PWS patients in general have normal muscle size but low muscle mass and their grip strength is diminished by about 25%, and PWS children have lower maximal muscle power and force relative to their body weight77,78. The sensory system is also implicated with skin-picking, a pathological behavior particularly prevalent in PWS and previously found in 69–95% of young PWS patients79 and 81% of adults80. Hall et al. suggested that this skin-picking was maintained by automatically produced sensory consequences81, and Hustyi et al. proposed that it might serve as sensory stimulation82, with both thus suggesting an alteration in the sensory pathway. In addition, an impairment in multisensory integration has been described with a lower gain in sensitivity in a multimodal condition compared with a control condition in visual–auditive combinations54.

PWS patients also present an autonomic nervous system dysfunction with a lower resting diastolic blood pressure and significantly less change in diastolic blood pressure after standing, which correlates significantly with the body mass index (BMI)83,84. In addition, several cardiac autonomic parameters differ during sleep between PWS patients and gender- and age-matched controls, with the patients showing altered parasympathetic activity84. Moreover, thermoregulation problems, resulting in hypo‐ or hyperthermia, have been infrequently reported in children with PWS85. Last, patients with PWS present gastrointestinal autonomic disorders characterized by an increased prevalence of prolonged total gastrointestinal transit time86, and delayed gastric emptying has generally been reported87.

Circuits

Interoceptive dysfunction has been detected in PWS patients, who show higher pain thresholds than controls88 with increased functional connectivity across the anterior cingular/insula and frontal regions89 and abnormal GABA-A receptor binding within the insula90. Klabunde et al. noted that the functional activation of interoceptive circuits occurs during skin-picking, and the relationship between insula activation and the severity of skin-picking suggests that this behavior may be reinforced by interoceptive consequences91. In addition, treatment with N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a derivative of the amino acid cysteine, is thought to act by either modulating NMDA glutamate receptors or increasing glutathione, and it has been associated with improvement in skin-picking behaviors92.

PWS patients also show small gray matter volume in the supplementary motor area, the caudate nucleus and the cerebellum with a hyperperfusion of the cerebellum62. The small gray matter volume in the cerebellum, as well as in the motor and sensory cortices, may be related to the central hypotonia in PWS28. In addition, the supplementary motor area and the caudate nucleus contribute to the control of movement. Interestingly, OXT treatment not only improves feeding skills, but also enhances spontaneous movements and improves coordination skills15. Moreover, it has been demonstrated in the mice model that Magel2 is required for normal strength and endurance and the maintenance of muscle mass93.

Conclusion

This review summarizes the current knowledge on the psychiatric symptoms observed in PWS patients and offers a new perspective through the RDoC matrix (Table 1). This work suggests the interest of constructing a developmental trajectory by combining the data on PWS collected from physiological, brain imaging, mice, and cell model studies. The brain imaging studies in PWS are usually limited by their sample size but that some results are comforted by several animal models very helpful. The early diagnosis of PWS enables us to investigate the neurodevelopmental and environmental influences on symptom emergence, such as the first changes in appetite and weight, which appear at ~9 months in PWS, the age at which complementary foods are first introduced to an infant’s diet94. Early diagnosis also facilitates the study of how modulating the environment can influence symptom improvement. One example is the setting of an energy-restricted and well-balanced diet before PWS children begin to develop excessive weight gain, as this has been shown to be efficient to reduce weight gain and fat mass95,96. Importantly, the neurodevelopmental aspect is illustrated by the differences observed for early and late treatment with OXT that confirm the therapeutic window relative to brain development. This observation is relevant, with studies demonstrating OXT circuit development in animal models, and underlines the need to take into account the brain specificities over the time for treatment97.

One of the issues for research in psychiatry, especially translational research, is the constitution of homogenous groups for the same diagnosis. The advantage of approaches that use the data of rare genetic disorders is that they are able to identify specific relationships between an objective marker and clinical manifestation through comprehensive animal models. We suggest that these observations will help identify therapeutic targets and biomarkers in psychiatry as supported by the RDoC framework and its multidimensional exploration. This hypothesis is supported by the RDoC framework, which proposes the multidimensional exploration of psychiatric disorders.

Exciting perspectives can then emerge, as well as new therapeutic approaches including genetic or epigenetic therapy. Indeed, reactivation of the SNORD116 gene in the Snord116 KO mice model improves the PWS phenotype98. Obviously, many steps are required before envisaging these treatments; however, the current scientific advances have opened up this field (or this possibility)99.

References

Kapur, S., Phillips, A. G. & Insel, T. Why has it taken so long for biological psychiatry to develop clinical tests and what to do about it? Mol. Psychiatry 17, 1174–1179 (2012).

Lai, M.-C. & Baron-Cohen, S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry 2, 1013–1027 (2015).

Xavier, J., Bursztejn, C., Stiskin, M., Canitano, R. & Cohen, D. Autism spectrum disorders: an historical synthesis and a multidimensional assessment toward a tailored therapeutic program. Res. Autism Spect. Dis. 18, 21–33 (2015).

Insel, T. et al. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 748–751 (2010).

Brainstorm Consortium, Anttila, V. et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science 360, 1–15 (2018).

Goldstone, A. P. Prader-Willi syndrome: advances in genetics, pathophysiology and treatment. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 15, 12–20 (2004).

Bennett, J. A., Hodgetts, S., Mackenzie, M. L., Haqq, A. M. & Zwaigenbaum, L. Investigating autism-related symptoms in children with Prader-Willi syndrome: a case study. nt. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 517 (2017).

Krefft, M., Frydecka, D., Adamowski, T. & Misiak, B. From Prader-Willi syndrome to psychosis: translating parent-of-origin effects into schizophrenia research. Epigenomics 6, 677–688 (2014).

von Deneen, K. M., Gold, M. S. & Liu, Y. Food addiction and cues in Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Addict. Med. 3, 19–25 (2009).

Tauber, M. et al. Prader-Willi syndrome as a model of human hyperphagia. Front. Hormone Res. 42, 93–106 (2014).

Dykens, E. M., Leckman, J. F. & Cassidy, S. B. Obsessions and compulsions in Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 37, 995–1002 (1996).

Singh, D., Wakimoto, Y., Filangieri, C., Pinkhasov, A. & Angulo, M. Guanfacine extended release for the reduction of aggression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, and self-injurious behavior in Prader-Willi syndrome—a retrospective cohort study. J.Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 29, 313–317 (2019).

Bar, C. et al. Early diagnosis and care is achieved but should be improved in infants with Prader-Willi syndrome. Orphan. J. Rare Dis. 12, 118 (2017).

Miller, J. L. et al. Nutritional phases in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 155A, 1040–1049 (2011).

Tauber, M. et al. The use of oxytocin to improve feeding and social skills in infants with Prader-Willi syndrome. Pediatrics 139, e20162976 (2017).

Tauber, M. et al. Oxytocin may be useful to increase trust in others and decrease disruptive behaviours in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome: a randomised placebo-controlled trial in 24 patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 6, 47 (2011).

Schaaf, C. P. Truncating mutations of MAGEL2 cause Prader-Willi phenotypes and autism. Nat. Genet. 45, 1405–1408 (2013).

Bieth, E. et al. Highly restricted deletion of the SNORD116 region is implicated in Prader-Willi syndrome. Euro. J. Hum. Genet. 23, 252–255 (2015).

Qi, Y. et al. Snord116 is critical in the regulation of food intake and body weight. Sci. Rep. 6, 18614 (2016).

Tauber, M. et al. Prader-Willi syndrome: a model for understanding the ghrelin system. J. Neuroendocrinol. 31, e12728 (2019).

Feigerlová, E. et al. Hyperghrelinemia precedes obesity in Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 2800–2805 (2008).

Beauloye, V. et al. High unacylated ghrelin levels support the concept of anorexia in infants with Prader-Willi syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 11, 56 (2016).

Polex-Wolf, J. et al. Hypothalamic loss of Snord116 recapitulates the hyperphagia of Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 960–969 (2018).

Burnett, L. C. et al. Deficiency in prohormone convertase PC1 impairs prohormone processing in Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 293–305 (2017).

Miller, J. L. et al. Enhanced activation of reward mediating prefrontal regions in response to food stimuli in Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 78, 615–619 (2007).

Holsen, L. M. et al. Neural mechanisms underlying hyperphagia in Prader-Willi syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 14, 1028–1037 (2006).

Holsen, L. M. et al. Importance of reward and prefrontal circuitry in hunger and satiety: Prader-Willi syndrome vs simple obesity. Int. J. Obesity 36, 638–647 (2012). (2005).

Ogura, K. et al. Small gray matter volume in orbitofrontal cortex in Prader-Willi syndrome: a voxel-based MRI study. Hum. Brain Mapping 32, 1059–1066 (2011).

Oliver, C. Annotation: self-injurious behaviour in children with learning disabilities: recent advances in assessment and intervention. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 36, 909–927 (1995).

Woodcock, K. A., Oliver, C. & Humphreys, G. W. A specific pathway can be identified between genetic characteristics and behaviour profiles in Prader-Willi syndrome via cognitive, environmental and physiological mechanisms. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 53, 493–500 (2009).

Skokauskas, N., Sweeny, E., Meehan, J. & Gallagher, L. Mental health problems in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Canad. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 21, 194–203 (2012).

Cavaillé, J. Box C/D small nucleolar RNA genes and the Prader-Willi syndrome: a complex interplay. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 8, https://doi.org/10.1002/wrna.1417 (2017).

Kishore, S. et al. The SnoRNA MBII-52 (SNORD 115) is processed into smaller RNAs and regulates alternative splicing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 1153–1164 (2010).

Akefeldt, A., Ekman, R., Gillberg, C. & Månsson, J. E. Cerebrospinal fluid monoamines in Prader-Willi syndrome. Biol. Psychiatry 44, 1321–1328 (1998).

Soni, S. et al. The course and outcome of psychiatric illness in people with Prader-Willi syndrome: implications for management and treatment. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 51(Pt 1), 32–42 (2007).

Bonnot, O. et al. Psychotropic treatments in Prader-Willi syndrome: a critical review of published literature. Euro. J. Pediatr. 175, 9–18 (2016).

Doe, C. M. et al. Loss of the imprinted SnoRNA Mbii-52 leads to increased 5htr2c pre-RNA editing and altered 5HT2CR-mediated behaviour. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 2140–2148 (2009).

Morabito, M. V. et al. Mice with altered serotonin 2C receptor RNA editing display characteristics of Prader-Willi syndrome. Neurobiol. Dis. 39, 169–180 (2010).

Pujol, J. et al. Anomalous basal ganglia connectivity and obsessive-compulsive behaviour in patients with Prader Willi syndrome. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 41, 261–271 (2016).

Roof, E. et al. Intellectual characteristics of Prader-Willi syndrome: comparison of genetic subtypes. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 44(Pt 1), 25–30 (2000).

Gross-Tsur, V., Landau, Y. E., Benarroch, F., Wertman-Elad, R. & Shalev, R. S. Cognition, attention, and behavior in Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Child Neurol. 16, 288–290 (2001).

Jauregi, J. et al. A neuropsychological assessment of frontal cognitive functions in Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 51(Pt 5), 350–365 (2007).

Cassidy, S. B. Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 34, 917–923 (1997).

Curfs, L. M., Wiegers, A. M., Sommers, J. R., Borghgraef, M. & Fryns, J. P. Strengths and weaknesses in the cognitive profile of youngsters with Prader-Willi syndrome. Clin. Genet. 40, 430–434 (1991).

Dykens, E. M., Hodapp, R. M., Walsh, K. & Nash, L. J. Adaptive and maladaptive behavior in Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 31, 1131–1136 (1992).

Foti, F. et al. Explorative function in Prader-Willi syndrome analyzed through an ecological spatial task. Res. Dev. Disabil. 38, 97–107 (2015).

Whittington, J. & Holland., T. Cognition in people with Prader-Willi syndrome: insights into genetic influences on cognitive and social development. Neurosc. Biobehav. Rev. 72, 153–167 (2017).

Chevalère, J. et al. Executive functions and Prader-Willi syndrome: global deficit linked with intellectual level and syndrome-specific associations. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 120, 215–229 (2015).

Puri, M. R., Sahl, R., Ogden, S. & Malik, S. Prader-Willi syndrome, management of impulsivity, and hyperphagia in an adolescent. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 26, 403–404 (2016).

Lukoshe, A., Hokken-Koelega, A. C., van der Lugt, A. & White, T. Reduced cortical complexity in children with Prader-Willi syndrome and its association with cognitive impairment and developmental delay. PloS ONE 9, e107320 (2014).

Whittington, J. & Holland, T. Recognition of emotion in facial expression by people with Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 55, 75–84 (2011).

Koenig, K., Klin, A. & Schultz, R. Deficits in social Attribution ability in Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Autism and Dev. Dis. 34, 573–582 (2004).

Debladis, J. et al. Face processing and exploration of social signals in Prader-Willi syndrome: a genetic signature. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 14, 262 (2019).

Salles, J. et al. Deficits in voice and multisensory processing in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Neuropsychologia 85, 137–147 (2016).

Strenilkov, K. et al. A study of voice and non-voice processing in Prader-Willi syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 15, 22 (2020).

Rosner, B. A., Hodapp, R. M., Fidler, D. J., Sagun, J. N. & Dykens, E. M. Social competence in persons with Prader-Willi, Williams and Downs syndromes. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 17, 209–217 (2004).

Dimitropoulos, A., Feurer, I. D., Butler, M. G. & Thompson, T. Emergence of compulsive behavior and tantrums in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 106, 39–51 (2001).

Dykens, E. M. & Roof, E. Behavior in Prader-Willi syndrome: relationship to genetic subtypes and age. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 49, 1001–1008 (2008).

Key, A. P., Jones, D. & Dykens, E. M. Social and emotional processing in Prader-Willi syndrome: genetic subtype differences. J. Neurodev. Dis. 5, 7 (2013).

Swaab, D. F., Purba, J. S. & Hofman, M. A. Alterations in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and its oxytocin neurons (Putative Satiety Cells) in Prader-Willi syndrome: a study of five cases. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 80, 573–579 (1995).

Ates, T. et al. Inactivation of Magel2 suppresses oxytocin neurons through synaptic excitation-inhibition imbalance. Neurobiol. Dis. 121, 58–64 (2019).

Mantoulan, C. et al. PET scan perfusion imaging in the Prader-Willi syndrome: new insights into the psychiatric and social disturbances. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 275–282 (2011).

Jennings, J. H. et al. Interacting neural ensembles in orbitofrontal cortex for social and feeding behaviour. Nature 565, 645–649 (2019).

Cohen, M., Hamilton, J. & Narang, I. Clinically important age-related differences in sleep related disordered breathing in infants and children with Prader-Willi syndrome. PLoS ONE 9, e101012 (2014).

Harris, J. C. & Allen, R. P. Is excessive daytime sleepiness characteristic of Prader-Willi syndrome? The effects of weight change. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 150, 1288–1293 (1996).

Miller, J. L. & Wagner, M. Prader-Willi syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatr. Ann. 42, 200–204 (2013).

Manni, R. L. et al. Hypersomnia in the Prader Willi syndrome: clinical-electrophysiological features and underlying factors. Clin. Neurophysiol. 112, 800–805 (2001).

Takahashi, J. S. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 164–179 (2017).

Coulson, R. L. et al. Snord116-dependent diurnal rhythm of DNA methylation in mouse cortex. Nat. Commun. 9, 1616 (2018).

Kozlov, S. et al. The imprinted gene Magel2 regulates normal circadian output. Nat. Genet. 39, 1266–1272 (2007).

Powell, W. T. et al. A Prader–Willi locus LncRNA cloud modulates diurnal genes and energy expenditure. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 4318–4328 (2013).

Nevsimalova, S. et al. Hypocretin deficiency in Prader-Willi syndrome. Euro. J. Neurol. 12, 70–72 (2005).

Omokawa, M. et al. Decline of CSF orexin (Hypocretin) levels in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 170A, 1181–1186 (2016).

Qi, Y. et al. Ambient temperature modulates the effects of the Prader-Willi syndrome candidate gene Snord116 on energy homeostasis. Neuropeptides 61, 87–93 (2017).

Ding, F. et al. SnoRNA Snord116 (Pwcr1/MBII-85) deletion causes growth deficiency and hyperphagia in mice. PLoS ONE 3, e1709 (2008).

Wijesuriya, T. M. et al. The Prader-Willi syndrome proteins MAGEL2 and Necdin regulate leptin receptor cell surface abundance through ubiquitination pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 4215–4230 (2017).

Edouard, T. et al. Muscle-bone characteristics in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, E275–E281 (2012).

Reus, L. et al. Objective evaluation of muscle strength in infants with hypotonia and muscle weakness. Res. Dev. Disabil. 34, 1160–1169 (2013).

Whitman, B. Y. & Accardo, P. Emotional symptoms in Prader-Willi syndrome adolescents. Am. J. Med. Genet. 28, 897–905 (1987).

Thornton, L. & Dawson, K. P. Prader-Willi syndrome in New Zealand: a survey of 36 affected people. N. Z. Med. J. 103, 97–98 (1990).

Hall, S. S., Hustyi, K. M., Chui, C. & Hammond, J. L. Experimental functional analysis of severe skin-picking behavior in Prader–Willi syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 35, 2284–2292 (2014).

Hustyi, K. M., Hammond, J. L., Rezvani, A. B. & Hall, S. S. An analysis of the topography, severity, potential sources of reinforcement, and treatments utilized for skin picking in Prader–Willi syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 34, 2890–2899 (2013).

DiMario, F. J., Dunham, B., Burleson, J. A., Moskovitz, J. & Cassidy, S. B. An evaluation of autonomic nervous system function in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Pediatrics 93, 76–81 (1994).

Haqq, A. M. et al. Autonomic nervous system dysfunction in obesity and Prader-Willi syndrome: current evidence and implications for future obesity therapies. Clin. Obes. 1, 175–183 (2011).

Ince, E. et al. Characteristics of hyperthermia and its complications in patients with Prader Willi syndrome. Pediatr. Int. 47, 550–553 (2005).

Kuhlmann, L., Joensson, I. M., Froekjaer, J. B., Krogh, K. & Farholt, S. A descriptive study of colorectal function in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome: high prevalence of constipation. BMC Gastroenterol. 14, 63 (2014).

Arenz, T., Schwarzer, A., Pfluger, Th., Koletzko, S. & Schmidt, H. Delayed gastric emptying in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 23, 867–871 (2010).

Priano, L. et al. On the origin of sensory impairment and altered pain perception in Prader-Willi syndrome: a neurophysiological study. Euro. J. Pain (London, England) 13, 829–835 (2009).

Zhang, Y. et al. Altered functional brain networks in Prader-Willi syndrome. NMR Biomed. 26, 622–629 (2013).

Lucignani, G. et al. GABA A receptor abnormalities in Prader-Willi syndrome assessed with positron emission tomography and [11C]Flumazenil. NeuroImage 22, 22–28 (2004).

Klabunde, M. et al. Neural correlates of self-injurious behavior in Prader-Willi syndrome. Hum. Brain Mapping 36, 4135–4143 (2015).

Miller, J. L. & Angulo, M. An open-label pilot study of N-acetylcysteine for skin-picking in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 164A, 421–424 (2014).

Kamaludin, A. A. et al. Muscle dysfunction caused by loss of Magel2 in a mouse model of Prader-Willi and Schaaf-Yang syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25, 3798–3809 (2016).

Salminen, I. I., Crespi, B. J. & Mokkonen, M. Baby food and bedtime: evidence for opposite phenotypes from different genetic and epigenetic alterations in Prader-Willi and angelman syndromes. SAGE Open Med. 7, 2050312118823585 (2019).

Crinò, A., Fintini, D., Bocchini, S. & Grugni, G. Obesity management in Prader-Willi syndrome: current perspectives. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 11, 579–593 (2018).

Miller, J. L., Lynn, C. H., Shuster, J. & Driscoll, D. J. A reduced-energy intake, well-balanced diet improves weight control in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Hum. Nutr. Dietetics 26, 2–9 (2013).

Fu, Y. & Depue, R. A. A novel neurobehavioral framework of the effects of positive early postnatal experience on incentive and consummatory reward sensitivity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 107, 615–640 (2019).

Kim, Y., Wang, S. E. & Jiang, Y.-H. Epigenetic therapy of Prader–Willi syndrome. Transl. Res. 208, 105–118 (2019).

Bochukova, E. G. et al. A transcriptomic signature of the hypothalamic response to fasting and BDNF deficiency in Prader-Willi syndrome. Cell Rep. 22, 3401–3408 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French Association for Prader–Willi Syndrome (grant R15062BB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salles, J., Lacassagne, E., Benvegnu, G. et al. The RDoC approach for translational psychiatry: Could a genetic disorder with psychiatric symptoms help fill the matrix? the example of Prader–Willi syndrome. Transl Psychiatry 10, 274 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-00964-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-00964-6

This article is cited by

-

Introducing a depression-like syndrome for translational neuropsychiatry: a plea for taxonomical validity and improved comparability between humans and mice

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

-

Differential volume reductions in the subcortical, limbic, and brainstem structures associated with behavior in Prader–Willi syndrome

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Patients with PWS and related syndromes display differentially methylated regions involved in neurodevelopmental and nutritional trajectory

Clinical Epigenetics (2021)

-

What can we learn from PWS and SNORD116 genes about the pathophysiology of addictive disorders?

Molecular Psychiatry (2021)