Abstract

Schizophrenia is substantially comorbid with type 2 diabetes (T2D), but the molecular basis of this effect is incompletely understood. Here, we show that a cortical schizophrenia expression score predicts glycemic control from pancreatic islet cell expression. We used machine learning to identify a cortical expression signature in 212 schizophrenia patients and controls, which explained ~25% of the illness-associated variance. The algorithm was predicted in expression data from 51 subjects (9 with T2D), explained up to 26.3% of the variance in the glycemic control indicator HbA1c and could significantly differentiate T2D patients from controls. The cross-tissue prediction was driven by processes previously linked to diabetes. Genes contributing to this prediction were involved in the electron transport chain as well as kidney development and support oxidative stress as a molecular process underlying the comorbidity between both conditions. Together, the present results suggest a molecular commonality between schizophrenia and glycemic markers of type 2 diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with schizophrenia die, on average, about two decades earlier than healthy peers, an excess mortality largely due to somatic illnesses such as type 2 diabetes (T2D)1. T2D prevalence is increased 2–3-fold compared with the general population and family history of the illness is more common2,3. While T2D can be a consequence of antipsychotic treatment, glycemic alterations have been found in antipsychotic naive subjects, supporting a disease intrinsic molecular comorbidity between the two conditions4,5. Although at the genome-wide level schizophrenia and T2D show no genetic correlation6, molecular investigations found shared biological alterations in both illnesses. These include elevated levels of insulin and closely related molecules such as IGF, a metabolic profile also found in treated as well as medication-naive patients with schizophrenia4,7. On a candidate gene basis, individual risk variants have been implicated in both conditions8, supporting shared underlying genetic determinants. At a systems level, mitochondrial dysfunction has been suggested as unifying biological theme underlying T2D and schizophrenia9,10. In schizophrenia, increased mitochondrial β oxidation and upregulation of insulin signaling proteins are thought to indicate a state of glucose/energy starvation in the prefrontal cortex that may, in turn, lead to increased oxidative stress9. In T2D, abnormal skeletal glucose transport plays a major part in the molecular etiology of insulin-resistant T2D11. This defect is thought to arise from fatty acid-induced inhibition of insulin receptor (IRS-1) phosphorylation, potentially due to intramyocellular fatty acid accumulation that may result from abnormal mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation11. At the same time, mitochondrial dysfunction in pancreatic β-cells leads to an increase of reactive oxygen species that is thought to underlay the progressive development of β-cell failure, a central part of the T2D pathology12. Despite these intriguing data, it remains unclear whether molecular commonality of these two disorders can be demonstrated at a biological systems level.

To address this, we used a machine learning approach to identify a polygenic schizophrenia signature and explored its impact on T2D (Supplementary Fig. S1). The first aim was to identify a signature of genes expressed in the human cortex that could optimally differentiate schizophrenia patients from healthy controls. For this, we used transcriptome-wide cortical expression data from 212 schizophrenia patients and controls. We then predicted this signature in independent pancreatic islet cell expression data from 51 individuals (9 T2D patients). We tested the hypothesis whether the predicted schizophrenia scores were associated with glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, a quantitative readout of glycemic control, where values above 6.5% have been suggested as a diagnostic test for diabetes13. The cross-tissue prediction performed here was based on the assumption that (I) schizophrenia is associated with molecular alterations that are at least partially systemic and can be detected in central as well as peripheral tissues and (II) that such alterations are consistent in the direction of their change. We tuned the polygenic model toward schizophrenia relevant biological processes, through pre-selection of genes among gene ontology categories most associated with genetic schizophrenia risk14. This also allowed exploration of whether peripheral effects of the schizophrenia signature were masked by those more strongly linked to risk, which may be more brain specific.

Methods

Data sets and preprocessing

Transcriptome-wide expression data from four post mortem data sets of schizophrenia patients and controls (GSE53987, GSE21138, GSE35977, and GSE12679) were used to identify a polygenic schizophrenia model in the brain. A data set of pancreatic islet cell expression (GSE38642) was used to test the association of a predicted schizophrenia score with glycemic control. A further data set comprising transcriptome-wide expression data from pancreatic beta cells (GSE25462), acquired from T2D patients and controls using laser capture microdissection, was used for validation of the cross-tissue prediction. Finally, frontal cortex expression data sets from patients with HIV encephalitis (GSE3489) and Alzheimer’s disease (GSE36980) were used as negative controls. Data sets were identified through manual search from the GEO database (freeze date for search February 2017) and details of the data sets can be found in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Out of six identified cortical post mortem expression data sets comprising schizophrenia patients, two (GSE17612 and GSE21935) were excluded due to high average age (70.6 years vs. 44.7 in the remaining four data sets). Data were preprocessed using the robust multi-array average function of the R package affy, performing background correction, log2 transformation, and quantile normalization15,16. Multiple reads mapping to the same gene symbol were averaged. To exclude potential outliers, we visually inspected the first two principal components determined for each data set and excluded one patient in GSE53987 and two in GSE21138. Expression data were filtered to contain only genes that overlapped across all discovery studies, resulting in a total gene number of 17,062. To make overall expression levels comparable between brain and pancreatic islet or negative control data, data were quantile normalized again based on the, respectively, overlapping set of measured genes.

Covariate adjustment and propensity score matching of expression data

To prevent an impact of potential covariates on the ability to derive a polygenic profile from expression data, data sets were first normalized with respect to these variables. Specifically, for each of the schizophrenia brain expression data sets, we determined residuals after regressing expression information from each gene against site, gender, age, and post mortem interval (PMI), as well as the second polynomial of age. If a data set contained more controls than patients, this step was preceded by propensity score matching to identify a 1:1 matched sample based on age, gender, and PMI. This was performed using the R library MatchIt17. Pancreatic islet expression data were residualized against the same covariates, except for site. Brain pH was not used as a covariate, since measures were not fully available for all data sets. The pancreatic beta-cell validation data, as well as the Alzheimer’s disease negative control data, were residualized against the same covariates. The former data set was additionally residualized against the first principal component determined from the entire expression data set. This was performed since the authors reporting this study showed the first principal component to capture sample measurement dependent effects on overall variation18. Since no metadata were available for the HIV negative control data set, this data set was residualized only against its first principal component.

Gene selection and comparison of expression levels across tissues

To identify genes to be used for algorithm training, we selected those part of gene ontology categories that have previously been associated with schizophrenia, based on genome-wide functional analysis of GWAS data14,19. The selection was performed among the genes linked to schizophrenia (single disorder analysis) and focused on gene ontology only, since of the 4949 gene sets that were investigated by the PGC and annotated by five databases (GO, KEGG, Panther, Reactome, TargetScan), 4550 were from the gene ontology14. Among these, we selected the top 200 categories to obtain a likely over-inclusive list of genes. Subsequently, we explored the impact of removing genes in the most schizophrenia-associated categories. For this, we removed genes in the top 0, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 categories and corrected the resulting P-values for the family-wise error rate (FWER) according to the method of Bonferroni.

To compare expression levels between brain and pancreatic tissue, we used RNA-Seq data from human tissue samples from the genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) project20, available from the Expression Atlas21. The conventional 0.5 FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon model per million reads mapped) was used as expression cut-off.

Machine learning strategy

The machine learning strategy employed here was aimed at deriving a signature from a data set with correlated variables and a variable number that greatly exceeded the number of samples. Therefore, we utilized a strategy devised for this purpose that consisted of the following steps22: (I) determine the top n genes associated with case–control status. We used linear correlation for this purpose and chose n to be the sample number divided by 10. This selection was made since expression data were expected to show sufficient effect sizes such that accurate classifiers can be derived from a relatively small number of good predictors23. (II) Build a binomial model for case–control prediction via penalized maximum likelihood to further reduce the variable number to the most important predictors. Five-fold cross-validation was used to identify the optimal lambda value that determines the number of predictors. (III) Residualize the outcome variable against these predictors using a binomial model. (IV) Repeat the procedure from step (I) m times. We chose m = 2, such that the total number of predictors remained below 5024. (V) Using these predictors, build a smoothly clipped absolute deviation-penalized binomial regression model for prediction of diagnosis. Again, cross-validation was used to identify the optimal lambda value. (VI) Predict the final model in the pancreatic islet data.

The benefit of this method is its ability to efficiently select important predictors and cope with potential correlation among them. Compared to its original implementation, we made one further adaptation that can substantially improve classifier performance. Instead of training the classifier on the entire data set, we repeatedly trained it on subsets of the training data and averaged the prediction outcome. This method is also known as bootstrap aggregation (“bagging”) and integral part of other powerful machine learning tools, such as random forests25. Since our training data consisted of four different brain expression data sets, we randomly selected two-thirds of patient and control samples from each data set individually and combined them to form the training data. For the brain expression data, classification performance was tested on the samples not used for training, averaged over 1000 repetitions of the procedure. Classification accuracy was measured using non-parametric correlation between predicted and actual glycemic control values and using Nagelkerke’s R2 from logistic regression for classification of schizophrenia.

To demonstrate the specificity of associations between the schizophrenia polygenic model and glycemic control, the analysis was repeated 1000 times, starting with permuted diagnosis information in the brain expression data. We determined an empirical P-value as the frequency of explained variance estimates at least as high as the one observed for the original diagnostic information.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was performed using the R package WGCNA26, using only control subjects of the residualized cortical schizophrenia expression data. This analysis was performed on the combined data (rather than consensus analysis across individual dat asets) since, due to the small sizes of individual data sets, removal of associations with potential confounders may be more robust in the combined data. We identified a soft-threshold (the lowest β value to lead to an R2 of >0.8027, in the present analysis β = 4) to fit a scale-free topology to the network. The weighted adjacency matrix was then transformed into topological overlap (TOM) and hierarchical clustering (using flashClust28) was used to identify modules from the TOM dissimilarity matrix (1-TOM). We used a relatively small minimum module size of 10 to allow identification of gene sets with low gene numbers that may have high cross-tissue predictiveness. Although small module sizes may lead to biologically less plausible modules, this risk was minimized in the present study by performing WGCNA on a preselected set of genes from few gene ontology categories.

Results

Identification of a cortical schizophrenia signature

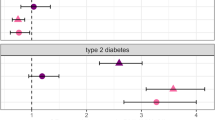

Machine learning was used to identify a cortical gene expression signature in 212 schizophrenia patients and controls. The model was built using genes within the 200 ontological categories that have previously been reported to be most strongly associated with genetic schizophrenia risk. Of these, 170 contained at least one gene measured across all investigated data sets (median number of genes was 14). Fig. 1a shows the polygenic model performance in schizophrenia brain expression data. The explained variance for classification of schizophrenia had a median of 25% with a median P-value of 6.1×10−9 and this did not depend on genes within ontological categories most associated with genetic schizophrenia risk. Specifically, performance was similar when genes part of the top 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 ontological categories were removed prior to machine learning analysis.

a Accuracy for HbA1c and case–control status prediction. The former was more accurate when the 60 ontological categories most associated genetic schizophrenia risk were excluded. b Association between the schizophrenia score and glycemic control. c Explained variance in glycemic control prediction for permuted and real schizophrenia diagnosis. SZ schizophrenia, HC healthy control

Association of predicted schizophrenia scores with glycemic control

Fig. 1a further shows that HbA1c levels could be predicted for all investigated gene sets below the FWER-corrected P-value threshold of 0.008. Notably, prediction performance peaked after removing genes within the top 60 ontological categories, suggesting that gene sets with the strongest genetic schizophrenia association were adversely affecting the prediction of glycemic control. At this threshold, the polygenic schizophrenia model explained 26.3% of variance in the glycemic control index (rho = −0.48, P = 0.0003, Fig. 1b) and differentiated T2D patients from healthy controls (P = 0.021, Wilcoxon test). Permuting diagnosis demonstrated the specificity of the findings for the real case–control status (P < 0.001, Fig. 1c, the median explained variance of schizophrenia classification during permutation was 0.8%). To explore the sensitivity of the results to the arbitrarily selected cut-off of 200 GO categories, the analysis was repeated for the 300 and 500 categories with the strongest genetic associations with schizophrenia. In both analyses, predicted schizophrenia scores were significantly associated with HbA1c levels (rho = -0.34, P = 0.015 and rho = −0.32, P = 0.023, respectively).

Next, we explored whether the bottom 200 ontological categories regarding genetic schizophrenia risk could also predict glycemic control. This was not the case with an explained variance of 3.9% (P = 0.17), even though the schizophrenia-control differentiation was not strongly affected (26% variance explained, P = 1.0×10−8).

Identification of genes underlying cross-tissue prediction

To identify ontological categories important for the cross-tissue prediction, we successively removed genes in each of the 140 remaining ontological categories from the analysis. Figure 2a shows the two most important categories were “kidney development” (GO:0001822) and “respiratory electron transport chain” (GO:0022904). WGCNA identified five gene modules among the two categories with one module of 22 genes contributing most to the decrease in explained variance (Fig. 2b). Among these, the four genes most strongly altered in schizophrenia were WFS1 (P = 1.8×10−7), angiotensinogen (AGT, P = 1.3×10−6), LRP4 (P = 2.7×10−6), and TNS2 (P = 9.3×10−4), all of which were increased in schizophrenia (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Table S3).

a Explained variance after excluding individual categories from the polygenic model, starting with the best model from Fig. 1. Circle radius is proportional to the number of genes part of the respective category. The solid line shows the mean explained variance, the dotted lines the 3.53 SD interval (FWER corrected at P = 0.05). b Explained variance after excluding individual modules from WGCNA of genes in the two categories shown in a. c Boxplots of the four genes in WGCNA module four most associated with schizophrenia. d Validation cohort: difference of predicted schizophrenia score between pancreatic beta cells of T2D patients and controls

GTEx RNA-seq data were used to compare expression levels of genes part of the cortical signature between brain and pancreatic tissue. This showed that 78% of the 2897 genes part of the 200 (170 represented with at least 1 gene) ontological categories most associated with schizophrenia risk were expressed in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA9) at a cut-off of 0.5 FPKM. For pancreatic tissue, this was the case for 70% of such genes. For genes part of the two identified ontological categories, the corresponding percentages were 82% (BA9) and 80% (pancreas), respectively. Supplementary Figure S2 shows a comparison of expression levels of these genes between tissue types.

Validation and negative control

To validate the cross-tissue prediction based on genes in the identified ontological categories, we used an additional, independent pancreatic expression data set, comprising 10 T2D patients and 10 healthy controls. Schizophrenia scores were predicted using all 162 genes part of the ontological categories “kidney development” and “respiratory electron transport chain” and which were shared between the brain and pancreatic expression data sets. The algorithm derived from these genes explained 23% of the variance (P = 2.7×10−8) for classification of schizophrenia. Prediction in pancreatic beta cells showed that T2D patients had significantly lower predicted schizophrenia scores compared to controls (P = 0.008, corrected for the influence of age and sex, Fig. 2d), consistent with findings from the pancreatic expression data set described above.

Two analyses were performed as a negative control. First, schizophrenia scores were predicted in a frontal cortex expression data set of subjects with HIV encephalitis (n = 16) and controls (n = 12) to support the specificity of the schizophrenia signature for prediction in comparable brain tissue samples. As above, the prediction was based on genes part of the two identified ontological categories and which overlapped with the schizophrenia data set (127 genes). This showed that predicted scores did not differ between HIV encephalitis patients and controls (P = 0.54).

Second, scores were predicted in frontal cortex expression data of subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (n = 15) and healthy controls (n = 18) using 162 overlapping genes of the two ontological categories. Also here, predicted schizophrenia scores were not associated with case–control status (P = 0.64, corrected for the influence of age and sex).

Discussion

Here, we show that a glycemic marker of T2D can be predicted using a schizophrenia brain expression score. This finding supports the presence of a systemic molecular commonality between schizophrenia and T2D. This is in agreement with studies identifying consistent alterations of individual molecules in the periphery and central nervous system of schizophrenia patients (e.g.,29). The association between the score and HbA1c levels was negative, meaning that subjects with a pancreatic islet profile more similar to that of schizophrenia patients had lower HbA1c levels. Consistent with this, T2D patients in this cohort as well as in an independent validation cohort had significantly lower schizophrenia scores compared to controls. There are several potential explanations for this finding. First, brain changes underlying the score may be of protective nature or affected by compensatory mechanisms. It is conceivable that such mechanisms are influenced by illness duration and the effects of antipsychotic medication. For example, a shared risk process may initially lead to comparable expression profiles. During later illness stages of schizophrenia, this process may be over-compensated, leading to an inversion of associations with HbA1c levels. This hypothesis could be examined by exploring potential interactions between the predicted schizophrenia score, pancreatic HbA1c levels, and illness duration. Such analysis would be particularly informative if schizophrenia patients would show similar expression profiles in peripheral cells. This would allow testing of samples from living and potentially untreated patients. A second possibility may be a shared risk mechanism that results in opposite expression effects in different tissues. To explore this, it would be interesting to investigate genetic risk overlap between schizophrenia and T2D in the identified processes. Potential joint risk signatures could then be examined regarding their tissue-specific, quantitative effects on expression.

Interestingly, prediction of HbA1c levels improved when gene sets with the highest genetic schizophrenia association were excluded. This implies that these genes were good predictors for schizophrenia with little relevance for HbA1c prediction. Therefore, their removal eliminated noise from the HbA1c prediction and led to improved performance. We further observed that genes relevant for the cross-tissue prediction clustered within the ontological categories more strongly linked to genetic schizophrenia risk. This may point toward genetic comorbidity effects within the identified signature but requires further elaboration.

We used data from subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and HIV encephalitis as a negative control for the present study. Interestingly, the pathology of both conditions has been linked to oxidative stress, supporting the specificity of the identified cortical signature for schizophrenia30,31.The two ontological categories contributing most to the prediction of glycemic control were “kidney development” and “respiratory electron transport chain”. While HbA1c levels are significantly predictive of chronic kidney disease32 and T2D is strongly associated with reduced kidney function and risk of kidney failure33,34, accumulating evidence suggests that the kidneys are directly involved in glucose homeostasis and insulin metabolism35. For example, insulin resistance is more frequent in patients with acute kidney injury36 and glucose uptake is decreased in uremia37. Renal glucose production and removal account for 25% and 20% of systemic production and removal, respectively38, supporting the kidneys’ central role in glucose homeostasis. Together, these reports suggest that kidneys play an important role in inducing abnormal glucose homeostasis and are also a target of the downstream consequences in the form of renal injury35.

The important predictive role of genes associated with the “respiratory electron transport chain” further supports mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress as the unifying theme underlying the comorbidity between schizophrenia and T2D9,10. The respiratory electron transport chain is a key part for oxidative phosphorylation of glucose, which has been identified as the most significantly downregulated pathway in schizophrenia post mortem brains9. It is also known to be deficient in skeletal muscle mitochondria of T2D patients39 and oxidative stress due to aberrant oxidative phosphorylation plays an important role in the development of diabetic nephropathy40. The predictive importance of oxidative phosphorylation and kidney-related genes identified here further supports their joint relevance for glucose homeostasis both in schizophrenia as well as T2D.

The most strongly implicated gene, WFS1, encodes the transmembrane protein Wolframin. Mutations in this gene can lead to Wolfram syndrome that presents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus41. Consistent with this, WFS1 variants have frequently been reported to contribute to T2D risk (e.g.,42,43,44). Two SNPs (rs10010131 and rs6446482) with intronic locations in the WFS1 gene are reproducibly associated with a protective effect on risk for T2D. The gene is characterized by a strong LD pattern and, albeit not consistently, evidence for further genetic risk associations has been reported. Meta-analysis investigating rs10010131 and rs734312 has confirmed significant protective effects for the minor alleles of both variants45, although the latter SNP may not be functionally relevant42. The risk allele of rs10010131 is further predictive of future T2D, progression from normal glucose tolerance to T2D46, as well as insulin secretion47. This allele has also been found to interact with a variant in hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (HNF4A) in an Ashkenazi Jewish Population, suggesting a potential gene–gene interaction effect on T2D risk48.

Interest in WFS1’s role in schizophrenia stems from observations that mutation carriers show an increased likelihood for psychiatric hospitalization49,50,51. Several subsequent genetic studies have investigated potential associations with schizophrenia risk, but these findings have thus far not supported a significant role52. For example, the T2D-associated variant rs10010131 has not been found associated with schizophrenia in a Danish cohort of 410 patients and 820 controls53. Similarly, WFS1 is not harbored by the well-established 108 genetic loci associated with schizophrenia risk54.

We further identified angiotensinogen as a gene important for the cross-tissue prediction in the present study. Angiotensinogen is a precursor of angiotensin I, a central part of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), an important regulator of glucose homeostasis55. In T2D, tissue RAS is activated leading to increased oxidative stress and progressive renal pathology [56]. While an angiotensinogen variant (rs699) that has previously been linked to hypertension, has not been found associated with T2D, such association has been identified for a variant in another gene central to the RAS (aldosterone synthase)57.

In schizophrenia, research into the RAS has focused on angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), which converts angiotensin I into angiotensin II but genetic association analyses have thus far been inconclusive58. The etiological role of the schizophrenia candidate gene ACE was initially thought to relate to its involvement in dopamine metabolism59,60. More recently, an ACE polymorphism has been shown to be associated with plasma glucose concentrations in chronic schizophrenia patients61. Together with the present findings, this may support the involvement of the RAS system in the comorbidity between schizophrenia and T2D, potentially due to their role in regulating glucose homeostasis.

A further gene important for cross-tissue prediction identified here is the LDL receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4). It belongs to the family of lipoprotein receptor-related proteins (LRPs) and antagonizes LRP6-mediated activation of canonical Wnt signaling. Mutations in this gene impact on such signaling and are associated with kidney anomalies in Cenani–Lenz Syndrome62. LRP5, a co-receptor of LRP6, has a central role in glucose-induced insulin secretion from pancreatic islets and for maintenance of normal cholesterol metabolism63. Polymorphisms in LRP5 are associated with obesity64 and variants in several other Wnt signaling genes have been linked to the development of T2D, most prominently in TCF7L265. Notably, Wnt signaling plays an important role in kidney development and regulates the expression of hormones essential for glucose homeostasis66.

Numerous studies have explored the role of Wnt signaling in schizophrenia, mainly due to its involvement in neuronal development67. Interestingly, a T2D risk variant in TCF7L2 has also been found to increase the risk for schizophrenia and this allele is associated with increased expression in pancreatic beta cells53. Further studies should explore the relationship between variation in Wnt signaling-related genes and glucose homeostasis as a potential factor underlying the comorbidity of schizophrenia and T2D. For example, another gene identified here, TNS2 (TENC1), has previously been found to interact with schizophrenia risk gene DISC168 and is involved in the regulation of Akt, an important modulator of Wnt signaling69,70.

The most significant limitation of the present study is that several confounding effects on the brain expression signature cannot be excluded. Although schizophrenia confers a significant endogenous risk for T2D, this risk is further increased by antipsychotic treatment71. Such medication effects may have influenced the identified cortical signature. Additional confounders include nicotine, alcohol, or drug use as well as the mode of death (i.e., suicide). Therefore, the molecular commonality identified in the present study should be interpreted as a state-dependent commonality between schizophrenia and T2D. Further studies are warranted to explore potential associations between this molecular overlap and factors underlying the genetic comorbidity between the conditions.

Conclusion

This study supports the presence of a molecular brain signature of schizophrenia that is associated with a glycemic marker of T2D in the periphery. These findings may help to elucidate the biological basis of comorbidity between the two illnesses. They may also aid in uncovering processes underlying the impact of antipsychotic treatment on T2D risk and highlight potential molecular targets for treatment of this clinically relevant comorbidity.

References

Ferentinos, P. & Dikeos, D. Genetic correlates of medical comorbidity associated with schizophrenia and treatment with antipsychotics. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 25, 381–390 (2012).

Mukherjee, S., Schnur, D. B. & Reddy, R. Family history of type 2 diabetes in schizophrenic patients. Lancet 1, 495 (1989).

Argo, T., Carnahan, R., Barnett, M., Holman, T. L. & Perry, P. J. Diabetes prevalence estimates in schizophrenia and risk factor assessment. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 23, 117–124 (2011).

Venkatasubramanian, G. et al. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 abnormalities in antipsychotic-naive schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 1557–1560 (2007).

Fernandez-Egea, E. et al. Metabolic profile of antipsychotic-naive individuals with non-affective psychosis. Br. J. Psychiatry 194, 434–438 (2009).

Bulik-Sullivan, B. et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat. Genet. 47, 1236–1241 (2015).

Guest, P. C. et al. Increased levels of circulating insulin-related peptides in first-onset, antipsychotic naive schizophrenia patients. Mol. Psychiatry 15, 118–119 (2010).

Lin, P. I. & Shuldiner, A. R. Rethinking the genetic basis for comorbidity of schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes. Schizophr. Res. 123, 234–243 (2010).

Prabakaran, S. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: evidence for compromised brain metabolism and oxidative stress. Mol. Psychiatry 9, 684–697 (2004). 643.

Lowell, B. B. & Shulman, G. I. Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Science 307, 384–387 (2005).

Parish, R. & Petersen, K. F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep. 5, 177–183 (2005).

Ma, Z. A., Zhao, Z. & Turk, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2012, 703538 (2012).

International Expert C. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 32, 1327–1334 (2009).

Network, Pathway Analysis Subgroup of Psychiatric Genomics C. Psychiatric genome-wide association study analyses implicate neuronal, immune and histone pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 199–209 (2015).

Irizarry, R. A. et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4, 249–264 (2003).

Gautier, L., Cope, L., Bolstad, B. M. & Irizarry, R. A. affy--analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics 20, 307–315 (2004).

HoKI, D. E. & King, G. EA Stuart MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J. Stat. Softw. 42, 1–28 (2011).

Marselli, L. et al. Gene expression profiles of beta-cell enriched tissue obtained by laser capture microdissection from subjects with type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 5, e11499 (2010).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29 (2000).

Consortium, G. T. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science 348, 648–660 (2015).

Petryszak, R. et al. Expression Atlas update--an integrated database of gene and protein expression in humans, animals and plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D746–D752 (2016).

Fan, J. Variable screening in high-dimensional feature space. ICCM 2, 735–747 (2007).

Schwarz, E. et al. Identification of a biological signature for schizophrenia in serum. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 494–502 (2012).

Schwarz, E. et al. Validation of a blood-based laboratory test to aid in the confirmation of a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Biomark. Insights 5, 39–47 (2010).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 559 (2008).

Zhang, B. & Horvath, S. A general framework for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 4, Article17 (2005).

Langfelder, P., Horvath, S. Fast R functions for robust correlations and hierarchical clustering. J. Stat. Softw. 46, i11 (2012).

Huang, J. T. et al. Independent protein-profiling studies show a decrease in apolipoprotein A1 levels in schizophrenia CSF, brain and peripheral tissues. Mol. Psychiatry 13, 1118–1128 (2008).

Perry, G., Cash, A. D. & Smith, M. A. Alzheimer disease and oxidative stress. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2, 120–123 (2002).

Masliah, E. et al. Patterns of gene dysregulation in the frontal cortex of patients with HIV encephalitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 157, 163–175 (2004).

Bash, L. D., Selvin, E., Steffes, M., Coresh, J. & Astor, B. C. Poor glycemic control in diabetes and the risk of incident chronic kidney disease even in the absence of albuminuria and retinopathy: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 168, 2440–2447 (2008).

Kramer, H. J., Nguyen, Q. D., Curhan, G. & Hsu, C. Y. Renal insufficiency in the absence of albuminuria and retinopathy among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 289, 3273–3277 (2003).

So, W. Y. et al. Glomerular filtration rate, cardiorenal end points, and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 29, 2046–2052 (2006).

Mehta, R. L. Glycemic control and critical illness: is the kidney involved? J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 2623–2627 (2007).

Mehta, R. L. et al. Spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit: the PICARD experience. Kidney Int. 66, 1613–1621 (2004).

Friedman, J. E. et al. Muscle insulin resistance in uremic humans: glucose transport, glucose transporters, and insulin receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 261, E87–E94 (1991).

Meyer, C., Dostou, J. M. & Gerich, J. E. Role of the human kidney in glucose counterregulation. Diabetes 48, 943–948 (1999).

Ritov, V. B. et al. Deficiency of electron transport chain in human skeletal muscle mitochondria in type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 298, E49–E58 (2010).

Forbes, J. M., Coughlan, M. T. & Cooper, M. E. Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes 57, 1446–1454 (2008).

Barrett, T. G. & Bundey, S. E. Wolfram (DIDMOAD) syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 34, 838–841 (1997).

Sandhu, M. S. et al. Common variants in WFS1 confer risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 39, 951–953 (2007).

Domenech, E., Gomez-Zaera, M. & Nunes, V. WFS1 mutations in Spanish patients with diabetes mellitus and deafness. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 10, 421–426 (2002).

Minton, J. A. et al. Association studies of genetic variation in the WFS1 gene and type 2 diabetes in U.K. populations. Diabetes 51, 1287–1290 (2002).

Cheng, S., Wu, Y., Wu, W. & Zhang, D. Association of rs734312 and rs10010131 polymorphisms in WFS1 gene with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Endocr. J. 60, 441–447 (2013).

Lyssenko, V. et al. Clinical risk factors, DNA variants, and the development of type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2220–2232 (2008).

Ruchat, S. M. et al. Association between insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity and type 2 diabetes susceptibility variants identified in genome-wide association studies. Acta Diabetol. 46, 217–226 (2009).

Neuman, R. J. et al. Gene-gene interactions lead to higher risk for development of type 2 diabetes in an Ashkenazi Jewish population. PLoS ONE 5, e9903 (2010).

Swift, R. G., Polymeropoulos, M. H., Torres, R. & Swift, M. Predisposition of Wolfram syndrome heterozygotes to psychiatric illness. Mol. Psychiatry 3, 86–91 (1998).

Swift, R. G., Perkins, D. O., Chase, C. L., Sadler, D. B. & Swift, M. Psychiatric disorders in 36 families with Wolfram syndrome. Am. J. Psychiatry 148, 775–779 (1991).

Swift, R. G., Sadler, D. B. & Swift, M. Psychiatric findings in Wolfram syndrome homozygotes. Lancet 336, 667–669 (1990).

Cryns, K. et al. Mutational spectrum of the WFS1 gene in Wolfram syndrome, nonsyndromic hearing impairment, diabetes mellitus, and psychiatric disease. Hum. Mutat. 22, 275–287 (2003).

Hansen, T. et al. At-risk variant in TCF7L2 for type II diabetes increases risk of schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 70, 59–63 (2011).

Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511, 421–427 (2014).

Putnam, K., Shoemaker, R., Yiannikouris, F. & Cassis, L. A. The renin-angiotensin system: a target of and contributor to dyslipidemias, altered glucose homeostasis, and hypertension of the metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302, H1219–H1230 (2012).

Giacchetti, G., Sechi, L. A., Rilli, S. & Carey, R. M. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, glucose metabolism and diabetes. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 16, 120–126 (2005).

Ichikawa, M. et al. Genetic variant of the renin-angiotensin system and prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a modest but significant effect of aldosterone synthase. Acta Diabetol. 51, 595–599 (2014).

Segman, R. H. et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism: case-control association studies in schizophrenia, major affective disorder, and tardive dyskinesia and a family-based association study in schizophrenia. Am. J. Med. Genet. 114, 310–314 (2002).

Jenkins, T. A. et al. Interactions of angiotensin II with central dopamine. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 396, 93–103 (1996).

Jenkins, T. A., Mendelsohn, F. A. & Chai, S. Y. Angiotensin-converting enzyme modulates dopamine turnover in the striatum. J. Neurochem. 68, 1304–1311 (1997).

Nadalin, S., Buretic-Tomljanovic, A., Ristic, S., Jonovska, S. & Tomljanovic, D. The impact of ACE gene I/D polymorphism on plasma glucose and lipid concentrations in schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res. 227, 71–72 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. LRP4 mutations alter Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and cause limb and kidney malformations in Cenani-Lenz syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86, 696–706 (2010).

Fujino, T. et al. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) is essential for normal cholesterol metabolism and glucose-induced insulin secretion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 229–234 (2003).

Guo, Y. F. et al. Polymorphisms of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) gene are associated with obesity phenotypes in a large family-based association study. J. Med. Genet. 43, 798–803 (2006).

Ip, W., Chiang, Y. T. & Jin, T. The involvement of the wnt signaling pathway and TCF7L2 in diabetes mellitus: the current understanding, dispute, and perspective. Cell. Biosci. 2, 28 (2012).

Pulkkinen, K., Murugan, S. & Vainio, S. Wnt signaling in kidney development and disease. Organogenesis 4, 55–59 (2008).

Freyberg, Z., Ferrando, S. J. & Javitch, J. A. Roles of the Akt/GSK-3 and Wnt signaling pathways in schizophrenia and antipsychotic drug action. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 388–396 (2010).

Millar, J. K., Christie, S. & Porteous, D. J. Yeast two-hybrid screens implicate DISC1 in brain development and function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311, 1019–1025 (2003).

Fukumoto, S. et al. Akt participation in the Wnt signaling pathway through Dishevelled. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 17479–17483 (2001).

Hafizi, S., Ibraimi, F. & Dahlback, B. C1-TEN is a negative regulator of the Akt/PKB signal transduction pathway and inhibits cell survival, proliferation, and migration. FASEB J. 19, 971–973 (2005).

Rajkumar, A. P. et al. Endogenous and antipsychotic-related risks for diabetes mellitus in young people with schizophrenia: a Danish population-based cohort study. Am. J. Psychiatry 174, 686–694 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), SCHW 1768/1-1 and has received funding from the Integrated Genome Research Network NGFNplus MooDS (Grant 01GS08147 to A.M.-L.) and from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no 602450 (IMAGEMEND, IMAging GENetics for MENtal Disorders. A.M.-L. acknowledges grant support by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, BMBF, through the Integrated Network IntegraMent (Integrated Understanding of Causes and Mechanisms in Mental Disorders) under the auspices of the e:Med Programme (BMBF grant no. 01ZX1314G) and the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking (IMI) under grant agreement no. 115300 (EU-AIMS) and no. 602805 (EU-Aggressotype).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.M.-L. received consultancy fees from Astra Zeneca, Elsevier, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, the Gerson Lehrman Group, The Lundbeck Foundation, Outcome Europe Sárl, Outcome Sciences, Roche Pharma, Servier International, and Thieme Verlag, and lecture fees, including the travel fees, from Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Aula Médica Congresos, Badische Anilin- & Soda-Fabrik, Groupo Ferrer International, Janssen Cilag, Lilly Deutschland, Landschaftsverband Rheinland Klinikum Düsseldorf, Servier Deutschland, and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. All other authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, H., Chen, J., Meyer-Lindenberg, A. et al. A polygenic score for schizophrenia predicts glycemic control. Transl Psychiatry 7, 1295 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-017-0044-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-017-0044-z

This article is cited by

-

Genetic analysis of the PCSK9 locus in psychological, psychiatric, metabolic and cardiovascular traits in UK Biobank

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)

-

Familial aggregation and shared genetic loading for major psychiatric disorders and type 2 diabetes

Diabetologia (2022)

-

Machine learning analysis of exome trios to contrast the genomic architecture of autism and schizophrenia

BMC Psychiatry (2020)