Abstract

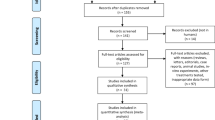

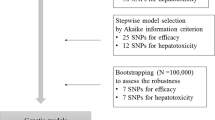

Leukopenia is a serious, frequent side effect associated with azathioprine use. Currently, we use thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) testing to predict leukopenia in patients taking azathioprine. We hypothesized that a risk score incorporating additional clinical and genetic variables would improve the prediction of azathioprine-associated leukopenia. In the discovery phase, we developed four risk score models: (1) age, sex, and TPMT metabolizer status; (2) model 1 plus additional clinical variables; (3) sixty candidate single nucleotide polymorphisms; and (4) model 2 plus model 3. The area under the receiver-operating-characteristic curve (AUC) of the risk scores was 0.59 (95% CI: 0.54–0.64), 0.75 (0.71–0.80), 0.66 (0.61–0.71), and 0.78 (0.74–0.82) for models 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. During the replication phase, models 2 and 4 (AUC = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.59–0.70 and AUC = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.58–0.69, respectively) were significant in an independent group. Compared with TPMT testing alone, additional genetic and clinical variables improve the prediction of azathioprine-associated leukopenia.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, Bombardieri S, Cervera R, Dostal C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:195–205.

Rispo A, Testa A, De Palma GD, Donetto S, Diaferia M, Musto D, et al. Different profile of efficacy of thiopurines in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2570–5.

Terdiman JP, Gruss CB, Heidelbaugh JJ, Sultan S, Falck-Ytter YT.AGA Institute Clinical Practice Quality Management Committee American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the use of thiopurines, methotrexate, and anti-TNF-alpha biologic drugs for the induction and maintenance of remission in inflammatory Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1459–63.

van Gelder T, van Schaik RH, Hesselink DA. Pharmacogenetics and immunosuppressive drugs in solid organ transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:725–31.

Kane SP. Azathioprine, ClinCalc DrugStats Database, Version 20.0. ClinCalc. 2019. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Azathioprine. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2018. https://www.ahrq.gov/data/meps.html. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

World Health Organization. WHO model list of essential medicines 2017. 2017. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/.

Zabala W, Cruz R, Barreiro-de Acosta M, M C, Panes J, Echarri A, et al. New genetic associations in thiopurine-related bone marrow toxicity among inflammatory bowel disease patients. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:631–40.

Roberts RL, Gearry RB. IMPDH1 promoter mutations in a patient exhibiting azathioprine resistance. Pharmacogenom J. 2007;7:312–7.

Matimba A, Li F, Livshits A, Cartwright CS, Scully S, Fridley BL, et al. Thiopurine pharmacogenomics: association of SNPs with clinical response and functional validation of candidate genes. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:433–47.

Shih DQ, Nguyen M, Zheng L, Ibanez P, Mei L, Kwan LY, et al. Split-dose administration of thiopurine drugs: a novel and effective strategy for managing preferential 6-MMP metabolism. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:449–58.

Toruner M, Loftus EV Jr., Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Orenstein R, Sandborn WJ, et al. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:929–36.

Roberts RL, Barclay ML. Update on thiopurine pharmacogenetics in inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16:891–903.

Broekman M, Coenen MJH, Wanten GJ, van Marrewijk CJ, Klungel OH, Verbeek ALM, et al. Risk factors for thiopurine-induced myelosuppression and infections in inflammatory bowel disease patients with a normal TPMT genotype. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:953–63.

Broekman M, Coenen MJH, van Marrewijk CJ, Wanten GJA, Wong DR, Verbeek ALM, et al. More dose-dependent side effects with mercaptopurine over azathioprine in ibd treatment due to relatively higher dosing. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1873–81.

Pulley J, Clayton E, Bernard GR, Roden DM, Masys DR. Principles of human subjects protections applied in an opt-out, de-identified biobank. Clin Transl Sci. 2010;3:42–8.

Roden DM, Pulley JM, Basford MA, Bernard GR, Clayton EW, Balser JR, et al. Development of a large-scale de-identified DNA biobank to enable personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:362–9.

Wei WQ, Denny JC. Extracting research-quality phenotypes from electronic health records to support precision medicine. Genome Med. 2015;7:41.

Yang SK, Hong M, Baek J, Choi H, Zhao W, Jung Y, et al. A common missense variant in NUDT15 confers susceptibility to thiopurine-induced leukopenia. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1017–20.

Varnell CD, Fukuda T, Kirby CL, Martin LJ, Warshaw BL, Patel HP, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil-related leukopenia in children and young adults following kidney transplantation: Influence of genes and drugs. Pediatr Transplant. 2017;21:e13033. https://doi.org/10.1111/petr.13033.

Kurzawski M, Dziewanowski K, Lener A, Drozdzik M. TPMT but not ITPA gene polymorphism influences the risk of azathioprine intolerance in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:533–40.

Honda K, Kobayashi A, Niikura T, Hasegawa T, Saito Z, Ito S, et al. Neutropenia related to an azathioprine metabolic disorder induced by an inosine triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase (ITPA) gene mutation in a patient with PR3-ANCA-positive microscopic polyangiitis. Clin Nephrol. 2018;90:363–9.

Ban H, Andoh A, Imaeda H, Kobori A, Bamba S, Tsujikawa T, et al. The multidrug-resistance protein 4 polymorphism is a new factor accounting for thiopurine sensitivity in Japanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1014–21.

Dubois PCA. The risk of azathioprine-induced pancreatitis depends on genetic variants in the HLA gene region. Gut 2011;60:A60.

Abla N, Chinn LW, Nakamura T, Liu L, Huang CC, Johns SJ, et al. The human multidrug resistance protein 4 (MRP4, ABCC4): functional analysis of a highly polymorphic gene. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:859–68.

Hawwa AF, Millership JS, Collier PS, Vandenbroeck K, McCarthy A, Dempsey S, et al. Pharmacogenomic studies of the anticancer and immunosuppressive thiopurines mercaptopurine and azathioprine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66:517–28.

Chiabai MA, Lins TC, Pogue R, Pereira RW. Population analysis of pharmacogenetic polymorphisms related to acute lymphoblastic leukemia drug treatment. Dis Markers. 2012;32:247–53.

Zelinkova Z, Derijks LJ, Stokkers PC, Vogels EW, van Kampen AH, Curvers WL, et al. Inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase and thiopurine s-methyltransferase genotypes relationship to azathioprine-induced myelosuppression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:44–9.

Uchiyama K, Takagi T, Iwamoto Y, Kondo N, Okayama T, Yoshida N, et al. New genetic biomarkers predicting azathioprine blood concentrations in combination therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95080.

Skrzypczak-Zielinska M, Borun P, Bartkowiak-Kaczmarek A, Zakerska-Banaszak O, Walczak M, Dobrowolska A, et al. A simple method for TPMT and ITPA genotyping using multiplex HRMA for patients treated with thiopurine drugs. Mol Diagn Ther. 2016;20:493–9.

Kurzawski M, Dziewanowski K, Safranow K, Drozdzik M. Polymorphism of genes involved in purine metabolism (XDH, AOX1, MOCOS) in kidney transplant recipients receiving azathioprine. Ther Drug Monit. 2012;34:266–74.

Lee MN, Kang B, Choi SY, Kim MJ, Woo SY, Kim JW, et al. Impact of genetic polymorphisms on 6-thioguanine nucleotide levels and toxicity in pediatric patients with IBD treated with azathioprine. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2897–908.

Krishnamurthy P, Schwab M, Takenaka K, Nachagari D, Morgan J, Leslie M, et al. Transporter-mediated protection against thiopurine-induced hematopoietic toxicity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4983–9.

Steinberg KK, Relling MV, Gallagher ML, Greene CN, Rubin CS, French D, et al. Genetic studies of a cluster of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cases in Churchill County, Nevada. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:158–64.

Carroll MB, Smith DM, Shaak TL. Genomic sequencing of uric acid metabolizing and clearing genes in relationship to xanthine oxidase inhibitor dose. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:445–53.

Eklund BI, Moberg M, Bergquist J, Mannervik B. Divergent activities of human glutathione transferases in the bioactivation of azathioprine. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:747–54.

Zhang W, Moden O, Mannervik B. Differences among allelic variants of human glutathione transferase A2-2 in the activation of azathioprine. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;186:110–7.

Stocco G, Pelin M, Franca R, De Iudicibus S, Cuzzoni E, Favretto D, et al. Pharmacogenetics of azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: a role for glutathione-S-transferase? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3534–41.

Hollman AL, Tchounwou PB, Huang HC. The association between gene-environment interactions and diseases involving the human GST superfamily with SNP variants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:379.

Silva SN, Azevedo AP, Teixeira V, Pina JE, Rueff J, Gaspar JF. The role of GSTA2 polymorphisms and haplotypes in breast cancer susceptibility: a case-control study in the Portuguese population. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:593–8.

Sylvester RK, Steen P, Tate JM, Mehta M, Petrich RJ, Berg A, et al. Temozolomide-induced severe myelosuppression: analysis of clinically associated polymorphisms in two patients. Anticancer Drugs. 2011;22:104–10.

Andonova IE, Justenhoven C, Winter S, Hamann U, Baisch C, Rabstein S, et al. No evidence for glutathione S-transferases GSTA2, GSTM2, GSTO1, GSTO2, and GSTZ1 in breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:497–502.

Ke HL, Lin J, Ye Y, Wu WJ, Lin HH, Wei H, et al. Genetic variations in glutathione pathway genes predict cancer recurrence in patients treated with transurethral resection and Bacillus Calmette-Guerin instillation for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:4104–10.

Mitrokhin V, Nikitin A, Brovkina O, Khodyrev D, Zotov A, Vachrushev N, et al. Association between interleukin-6/6R gene polymorphisms and coronary artery disease in Russian population: influence of interleukin-6/6R gene polymorphisms on inflammatory markers. J Inflamm Res. 2017;10:151–60.

Song GG, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Lee YH. Genome-wide pathway analysis of a genome-wide association study on multiple sclerosis. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:2557–64.

Heap GA, Weedon MN, Bewshea CM, Singh A, Chen M, Satchwell JB, et al. HLA-DQA1-HLA-DRB1 variants confer susceptibility to pancreatitis induced by thiopurine immunosuppressants. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1131–4.

Zabala-Fernández W, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Echarri A, Carpio D, Lorenzo A, Castro J, et al. A pharmacogenetics study of TPMT and ITPA genes detects a relationship with side effects and clinical response in patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving azathioprine. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2011;20:247–53.

Park SK, Hong M, Ye BD, Kim KJ, Park SH, Yang DH, et al. Influences of XDH genotype by gene-gene interactions with SUCLA2 for thiopurine-induced leukopenia in Korean patients with Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:684–91.

Moriyama T, Nishii R, Perez-Andreu V, Yang W, Klussmann FA, Zhao X, et al. NUDT15 polymorphisms alter thiopurine metabolism and hematopoietic toxicity. Nat Genet. 2016;48:367–73.

Reiner AP, Lettre G, Nalls MA, Ganesh SK, Mathias R, Austin MA, et al. Genome-wide association study of white blood cell count in 16,388 African Americans: the continental origins and genetic epidemiology network (COGENT). PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002108.

Ibanez L, Velli PS, Font R, Jaen A, Royo J, Irigoyen D, et al. HIV-infection, atherosclerosis and the inflammatory pathway: candidate gene study in a Spanish HIV-infected population. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112279.

Schaefer BA, Flanagan JM, Alvarez OA, Nelson SC, Aygun B, Nottage KA, et al. Genetic modifiers of white blood cell count, albuminuria and glomerular filtration rate in children with sickle cell anemia. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0164364.

Dickson A, Stanley B, Anandi P, Kawai V, Birdwell K, Hung A, et al. Development and validation of algorithms using electronic health records to identify azathioprine use and azathioprine-induced leukopenia for pharmacogenetic studies [abstract]. San Diego, CA: American Society of Human Genetics; 2018.

Turner S, Armstrong L, Bradford Y, Carlson C, Crawford D, Crenshaw A, et al. Quality control procedures for genome-wide association studies. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2011;1.19.1–1.19.18.

Das S, Forer L, Schonherr S, Sidore C, Locke AE, Kwong A, et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1284–7.

rs1800584 Frequency (updated 1/8/2019). https://useast.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Variation/Population?db=core;r=6:18130281-18131281;v=rs1800584;vdb=variation;vf=104059606.

Relling MV, Gardner EE, Sandborn WJ, Schmiegelow K, Pui CH, Yee SW, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for thiopurine methyltransferase genotype and thiopurine dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:387–91.

Jostins L, Barrett J. Genetic risk prediction in complex disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:R182–8.

Hessels AC, Rutgers A, Sanders JSF, Stegeman CA. Thiopurine methyltransferase genotype and activity cannot predict outcomes of azathioprine maintenance therapy for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis: a retrospective cohort study. PloS ONE. 2018;13:e0195524–e.

Walker G, Harrison J, Heap G, Voskuil M, Andersen V, Anderson C, et al. Association of genetic variants in NUDT15 with thiopurine-induced myelosuppression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA. 2019;321:773–85.

Project G. rs746071566 Frequency. 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs746071566#frequency_tab.

Ensembl. rs746071566 Frequency. 2019. https://useast.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Variation/Population?db=core;r=13:48037283-48038288;v=rs746071566;vdb=variation;vf=45794599.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grant R01GM126535 R01GM109145, R35GM131770, and by the Rheumatology Research Foundation K-supplement and R01 bridge awards. PA was supported by grants T32AR059039 and T32GM007569. VKK was supported by NIH/NIGMS K23GM117395 and the National Arthritis Research Foundation—All Arthritis Grant Program Award. CPC was also supported by grant AR073764. The dataset(s) used for the analyses described were obtained from Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s BioVU which is supported by numerous sources: institutional funding, private agencies, and federal grants. These include the NIH funded Shared Instrumentation Grant S10RR025141; and CTSA grants UL1TR002243, UL1TR000445, and UL1RR024975. Genomic data are also supported by investigator-led projects that include U01HG004798, R01NS032830, RC2GM092618, P50GM115305, U01HG006378, U19HL065962, R01HD074711; and additional funding sources listed at https://victr.vumc.org/biovu/index.html?sid=229. The funding sources had no role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing of the paper, or decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anandi, P., Dickson, A.L., Feng, Q. et al. Combining clinical and candidate gene data into a risk score for azathioprine-associated leukopenia in routine clinical practice. Pharmacogenomics J 20, 736–745 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41397-020-0163-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41397-020-0163-4

This article is cited by

-

Precision medicine for rheumatologists: lessons from the pharmacogenomics of azathioprine

Clinical Rheumatology (2021)

-

A case-control study of a combination of single nucleotide polymorphisms and clinical parameters to predict clinically relevant toxicity associated with fluoropyrimidine and platinum-based chemotherapy in gastric cancer

BMC Cancer (2021)