Abstract

Pseudomonas protegens shows a high degree of lifestyle plasticity since it can establish both plant-beneficial and insect-pathogenic interactions. While P. protegens protects plants against soilborne pathogens, it can also invade insects when orally ingested leading to the death of susceptible pest insects. The mechanism whereby pseudomonads effectively switch between lifestyles, plant-beneficial or insecticidal, and the specific factors enabling plant or insect colonization are poorly understood. We generated a large-scale transcriptomics dataset of the model P. protegens strain CHA0 which includes data from the colonization of wheat roots, the gut of Plutella xylostella after oral uptake and the Galleria mellonella hemolymph after injection. We identified extensive plasticity in transcriptomic profiles depending on the environment and specific factors associated to different hosts or different stages of insect infection. Specifically, motor-activity and Reb toxin-related genes were highly expressed on wheat roots but showed low expression within insects, while certain antimicrobial compounds (pyoluteorin), exoenzymes (a chitinase and a polyphosphate kinase), and a transposase exhibited insect-specific expression. We further identified two-partner secretion systems as novel factors contributing to pest insect invasion. Finally, we use genus-wide comparative genomics to retrace the evolutionary origins of cross-kingdom colonization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pseudomonas is a highly versatile genus that comprises bacteria living in diverse environments and that colonizes an ecologically broad range of hosts [1,2,3]. Some pseudomonads are pathogens of plants or animals such as fish, insects, or mammals [3, 4]. Members of the Pseudomonas fluorescens group [1, 2] are known plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria that stimulate plant growth, induce systemic resistance against foliar diseases and control soilborne fungal pathogens [5,6,7,8]. Due to these characteristics, several Pseudomonas-based biocontrol products are currently deployed to control fungal and bacterial diseases [9, 10]. Microbial-based methods for pest control will be crucial in future agricultural practices because an increasing number of chemical fungicides and insecticides is already or will likely be banned due to environmental and health concerns [11,12,13]. Within the P. fluorescens group, the two species Pseudomonas protegens and Pseudomonas chlororaphis are particularly interesting for plant protection applications because, unlike other biocontrol pseudomonads, they are crop plant colonizers with antifungal activity and pest insect colonizers with insecticidal activity [14,15,16].

P. protegens and P. chlororaphis colonize the insect gut after oral intake and transmigrate into the hemolymph, causing systemic infections and the eventual death of several Lepidoptera, Diptera, Coleoptera, and Hemiptera insect species [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. The P. fluorescens subgroup [2] harbors insecticidal strains with lower pathogenicity than the P. protegens/P. chlororaphis species [14, 16, 18, 22]. In addition, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas entomophila are also able to infect and kill different insect species, through different mechanisms [24, 25].

The first insecticidal trait discovered was the Fit toxin [17] typically produced by strains belonging to the P. protegens and P. chlororaphis species [16]. The contribution of this protein toxin to oral and systemic insecticidal activity and its tight insect host-dependent regulation were studied in some detail in P. protegens type strain CHA0 [15, 20, 26, 27]. Fit toxin production only partially explains the insecticidal capabilities of these bacteria as fit deletion mutants retain some toxicity [15, 20]. Studies on P. protegens CHA0 and other P. protegens/P. chlororaphis strains related insecticidal activity and host persistence to additional factors, including type VI secretion components [28], chitinase and phospholipase C [16], hydrogen cyanide [29], the cyclic lipopeptide orfamide [29, 30], the toxins rhizoxin [31] and IPD072Aa [32], and specific lipopolysaccharide O-antigens [33]. P. protegens/P. chlororaphis strains can also cause nonlethal infections [18, 22, 23, 31]. Even if the infection does not kill the insect after oral uptake, strains such as CHA0 can persist until pupal and imago stages, thus affecting the insect development as shown for Delia radicum, Plutella xylostella and Pieris brassicae, and be transmitted to new host plants by D. radicum [23]. Therefore, the ability of P. protegens to colonize cross-kingdom insect and plant hosts is impressively demonstrated by work on the model strain CHA0. However, it remains largely unknown what specific traits underlie cross-kingdom host colonization and how plastic responses including transcriptional remodeling contribute to switching between hosts.

We analyzed the transcriptome of P. protegens CHA0 during the colonization of plant roots, as well as from different compartments of insect hosts, specifically the hemolymph and gut, representing different stages of infection. We provide the first evidence for transcriptome remodeling underlying switches between insect pathogenic and plant beneficial lifestyles. We showed that CHA0 uses a host-specific set of tools for roots and for different insect compartments. Finally, we use genus-wide comparative genomics to retrace the evolutionary origins of cross-kingdom host colonization.

Material and methods

Preparation of P. protegens CHA0 samples from different hosts and environments

For each host/environment four independent replicate samples were prepared. From all samples an aliquot was used for assessment of bacterial numbers by plating serial dilutions onto King’s B+++ agar (see Supplementary Methods) [34, 35]. The remaining samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Grace’s insect medium (GIM) and lysogeny broth (LB)

P. protegens CHA0 was grown on KB+++ agar for two days. Single colonies were transferred to LB [36] or GIM (Sigma Aldrich, MO, USA) and grown to OD600 = 1.74–1.86 (~1.5 × 109 cells/ml) at 24 °C while shaking at 180 rpm. Four milliliters of cultures were centrifuged (7500 rpm) and pellets used for RNA extractions.

Wheat roots

Root colonization assays were performed as described in de Werra et al. [37] and further explained in Supplementary Methods. Briefly, pre-germinated seeds of spring wheat, variety Rubli, were inoculated with 1 ml of a suspension containing 108 CHA0 cells/ml and placed into seed germination pouches. Plants were grown at 22 °C and 60% humidity with a 16/8 h day (270 μmol m−2 s−1)/night cycle. After 1 week, roots of 99 wheat plants per replicate were harvested, shaken in 0.9% NaCl, the resulting suspensions were centrifuged and pellets containing bacteria were pooled for RNA extraction.

P. xylostella gut (oral infection)

P. xylostella eggs were kept before and during the experiment at 25 °C, 60% relative humidity and a 16/8 h day/night cycle with 162 μmol m−2 s−1. Second instar P. xylostella were fed with pellets of artificial diet spiked with 4 × 106 CHA0 cells or NaCl 0.9% (control) as previously described by Flury et al. [29] and further explained in Supplementary Methods. For each replicate 120 treated alive larvae were collected 24 or 36 h post-feeding, surface disinfected and homogenized and homogenates were pooled. Sixty-three to sixty-five larvae per treatment were used for assessing survival over time. In addition, the resident cultivable microflora of untreated insects was assessed by growing the extracts on LB media plates at 18, 24, and 37 °C for 1 week.

G. mellonella hemolymph (hemocoel injection)

Seventh instar G. mellonella larvae were injected with 2 × 103 CHA0 cells or 0.9% NaCl solution as previously described by Flury et al. [29] and further explained in Supplementary Methods. After 24 h, 55 alive non-melanized larvae per replicate were surface disinfected, one leg was cut and the hemolymph collected. Thirty to fifty larvae per treatment were used to assess survival.

RNA extraction and sequencing

The range of total numbers of CHA0 cells used for sequencing were: LB, 5.6–5.9 × 109; GIM, 5.5–5.9 × 109; wheat, 5 × 108–2 × 1010; P. xylostella 24 h, 2.8 × 106–4.1 × 107; P. xylostella 36 h, 2.4 × 106–1.6 × 108; and G. mellonella, 8.2 × 107–2.2 × 109 cells. RNA from insect and media samples was extracted using the GENEzol Reagent (Geneaid International, Taiwan) and from wheat root samples using the RNeasy Plant Mini KitTM (Qiagen, Germany) without bead-ruption. All extracts were treated with DNase from the RNeasy Mini KitTM (Qiagen, Germany). RNA quality was assessed using the 2200 Tapestation (Agilent, CA, USA) and Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). For details, see Supplementary Table S1. Libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit. The RiboZero Bacteria kit was used for medium samples, RiboZero Epidemiology for insect samples and Ribozero Plant Root for wheat samples to remove bacterial, insect and plant rRNA, respectively (Illumina, CA, USA). Samples were sequenced using Illumina NextSeq500 single-end 81 bp sequencing (Illumina, CA, USA) at the Genomics Facility BSSE in Basel, Switzerland.

Bioinformatics analysis

Read trimming, alignment, and normalization

Raw reads were quality trimmed and filtered for adapter contamination with Trimmomatic 0.36 [38]. Processed reads were aligned against the P. protegens CHA0 genome (NCBI entry number LS999205.1, [39]) using STAR 2.3.5a [40]. Mapped reads were counted with featurecounts 1.5.3 [41] using the stranded option and normalized with the TMM (trimmed mean of M values) method [42] of the edgeR 3.26.6 package [43] in R 3.6.0 (www.r-project.org). Genes with <1 count per million (CPM) in the four biological replicates were discarded. Normalized CPM were used for: (1) a multidimensional scaling analysis; (2) a transcriptome profile analysis with the K-means algorithm. The optimal number of clusters was assessed with the sum of square error method, which showed that six clusters can optimally predict the different transcription patterns; (3) a differential gene expression (DGE) analysis following the general linear model from edgeR package [43, 44]. The differentially expressed genes were determined using “glmFit” function with a Benjamin–Hochberg FDR correction for false positives; (4) Log10 transformation and heatmap generation with heatmap.2 package (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gplots).

Finally, predicted P. protegens CHA0 coding genes were assigned to Gene Ontology (GO) terms using InterproScan 5.27-66.0 [45]. A GO database was generated with GO.db 3.8.2 package [46]. All DGE genes and transcription profile main clusters genes were used in GO enrichment with GOstats 1.7.4 package in R [47].

Ortholog analysis

Whole protein sequences of 97 Pseudomonas species (Supplementary Table S2) were compared using OrthoFinder 2.3.3 [48] in an orthologue protein analysis with the default settings. Results were then filtered for chosen categories of proteins. The tree output was represented using FigTree 1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/).

The detailed RNA-seq Script is placed in Supplementary Material 2.

RT-qPCR

In order to verify the RNA-seq results, the expression of selected genes pap, chiD, pltA, tpsA2, tpsA4, and the PPRCHA0_1961 IS3 transposase gene in the investigated environments/hosts were quantified using RT-qPCR as described in Supplementary Methods, and Supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

Role of two-partner secretion (TPS) proteins

Domains of tpsA1, tpsA2, tpsA3, and tpsA4 encoded proteins were predicted using the HMMER database (www.hmmer.org). The tpsA deletion mutants of CHA0 were constructed as described in Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table S5 and tested for insecticidal activity in feeding assays of 32 or 64 P. xylostella larvae and in injection assays of 18 G. mellonella larvae as previously described.

Statistics of insect assays

Survival data in the P. xylostella feeding and G. mellonella injection assays were evaluated using a Log-Rank test of the Survival package of R 3.6.0 (www.r-project.org) with a p value < 0.05.

Results and discussion

We analyzed the transcriptomic plasticity enabling P. protegens CHA0 to colonize lepidopteran larvae and wheat roots. These constitute two very different ecological niches in which CHA0 is known to establish pathogenic and beneficial interactions, respectively. We used the CHA0 strain to inoculate wheat roots, feed P. xylostella larvae or inject the hemocoel of G. mellonella larvae.

We analyzed the transcriptome of CHA0 after 1 week on wheat roots, when bacteria had established population sizes of 106–107 CFU/mg dry root (Fig. 1b). At this time point, where roots elongate fast, we expect the transcriptome to represent the whole spectrum of bacterial root colonization with already established microcolonies on older roots and continuing growth towards the root tips. In addition, the absence of resident microflora from the soil or the plant, allowed us to observe transcriptomic variation exclusively in response to the plant.

The “Wheat” samples correspond to wheat-roots 1 week after inoculation, “P. xylostella 24/36 h” to Plutella xylostella 24 and 36 h after oral infection; “G. mellonella” to Galleria mellonella hemolymph 24 h after hemocoel injection; “LB” to lysogeny broth, and “GIM” to Grace’s insect medium. a Survival of P. xylostella larvae after exposure to artificial diet pellets spiked with 4 × 106 CHA0 cells (top) and of G. mellonella larvae upon injection of 2 × 103 CHA0 cells (bottom). One representative experiment with 64 (Plutella) and 30 (Galleria) larvae is shown. Time points where insects were sampled for RNA extraction are indicated with arrows. b Bacterial densities at collection time points. Boxplots are created from four replicates per environment and show CFU per mg of root dry weight (wheat), CFU per mg of larvae (24/36 h), CFU per µl hemolymph (G. mellonella) and CFU per ml medium (GIM, LB). c Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) analysis was performed with four replicate CHA0 transcriptomes per environment. The different replicates of the different biological samples are numbered from 1 to 4.

P. xylostella was selected as model to study the progress of insect gut infection 24 and 36 h after feeding. Previous microscopy studies showed that, 1–2 days after feeding P. xylostella with treated pellets, CHA0 could only be found in the microvilli of the gut cells and, 3 days after feeding, the insect hemocoel was already heavily colonized by CHA0 [23]. In addition, P. xylostella larvae were shown to only harbor up to 100 cultivable CFU (including bacteria and fungi) of resident microorganisms per larvae at the moment of feeding with CHA0 (Supplementary Fig. 1c). In our study, at 24 h, the larvae showed no disease symptoms yet and were colonized by 104–105 CFU/mg larvae (Fig. 1a, b). At 36 h bacterial loads were ten times higher, some treated larvae started to die and the remaining were smaller and darker than non-treated larvae, indicating the start of bacterial transmigration from gut to hemocoel (Fig. 1a, b). Final mortality assessed in non-extracted P. xylostella was 90.6–98.4% (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S2). When CHA0 transmigrates into the hemocoel, it causes a systemic infection and eventually kills the insects.

Next, we wanted to understand the transcriptomic response in a pure hemolymph environment excluding transmigration factors. Therefore, we injected CHA0 directly into the hemocoel of the bigger insect model G. mellonella and extracted RNA 24 h later when the larvae were still alive, non-melanized and inoculant cell numbers had reached 105 CFU/µl hemolymph (Fig. 1b). CHA0 killed 93.3–100% of G. mellonella larvae within 48 h (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S2). We used the G. mellonella injection model because to inject P. xylostella larvae without causing harm and to extract enough hemolymph for RNA sequencing without disrupting the gut is very difficult due to their small size.

In addition to CHA0 transcriptome remodeling on insect hosts, we analyzed the bacterial response to an insect-simulating culture medium without the influence of host immune responses i.e., GIM. Finally, the transcriptome of CHA0 was analyzed when growing in a rich culture medium (Lysogeny broth).

We obtained 108–109 reads from RNA Illumina NextSeq sequencing for each sample and quantified expression levels of CHA0 gene models (Supplementary Table S1). We performed a multidimensional scaling analysis to distinguish CHA0 transcriptomes according to the colonized host or culture condition (Fig. 1c). All transcriptomes were differentially separated except for the P. xylostella at 24 and 36 h due to the differences in infection progression across the biological samples. The first principal component axis of Fig. 1c separates the transcriptomes from culture media from those obtained from living hosts. This is probably due to the fact that bacteria need to actively colonize both wheat and insect hosts even though bacteria do not establish a pathogenic interaction on roots. This may explain the position of the wheat transcriptome between the culture media and the insect backgrounds. The second principal component separates P. xylostella gut and G. mellonella hemolymph samples (Fig. 1c). Some differences in gene expression between gut and hemolymph environments may be due to the different lepidopteran species used. However, CHA0 was shown to multiply in and kill larvae of different lepidopteran species following a similar pattern [15, 16, 20, 23, 26, 28]. Figure 1c also shows the transcriptome plasticity within the same insect species probably due to the implication of different bacterial factors at different phases in the infection.

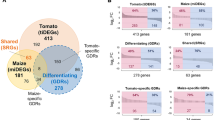

Pronounced differences between CHA0 transcriptomes during the colonization of wheat roots and insects

The clustering analysis revealed distinct expression profiles for each of the hosts and culture condition (Fig. 2a). This implies that the CHA0 transcriptome changes drastically according to the colonized plant or insect host. We also monitored pronounced differences between the P. xylostella gut and the G. mellonella hemolymph, which indicates that a different set of genes is active in different insect compartments. But we cannot exclude that some of the observed differences might be due to the use of two different insect species.

a Normalized counts per million (CPM) of P. protegens CHA0 transcriptomes obtained using the K-means clustering method. Genes clustered in six different groups according to different hosts/media. Standard errors for four biological replicates show small variations among the genes included in each cluster. The number of genes that belong to the main cluster of each transcription profile are indicated. From each cluster, those genes with a gene ontology (GO) annotation were used in the enrichment analyses presented in b. b Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the specific genes of each transcription profile main cluster. Significant GO terms for the given set of genes are shown. The number of total genes related to a GO term present in the CHA0 genome is given between brackets and the indicated percentage shows how many of those have higher expression in the specific transcription profile (p value < 0.001). BP biological process, MF molecular function. Redundant GO terms were merged. The “Wheat” sample corresponds to wheat-roots 1 week after inoculation, “P. xylostella 24/36 h” to Plutella xylostella 24 and 36 h after oral infection; “G. mellonella” to Galleria mellonella hemolymph 24 h after hemocoel injection, “LB” to lysogeny broth; “GIM” to Grace’s insect medium.

We found that general metabolic processes and genes related to organic compound biosynthesis were upregulated on wheat roots (Figs. 2b and 3a). Genes related to nucleotide and protein synthesis were downregulated during insect colonization compared to wheat roots (Fig. 3a). This might indicate that at the chosen time points the bacterium was more metabolically active on the roots e.g., colonizing growing root zones, whereas bacterial growth may have been restricted in the gut. Though, our study reflects only specific moments in time and we cannot generally conclude that proliferation on the roots was higher than proliferation in the gut. Observed differences in gene expression could be caused by host-derived factors or by differences in growth rate or population sizes. This implies that the CHA0 transcriptome changes significantly depending on the colonized plant or insect. We also found pronounced differences between P. xylostella gut and G. mellonella hemolymph suggesting that a different set of genes is used for different insect compartments. However, the use of two insect species may influence on the observed differences.

CHA0 transcriptomes colonizing different hosts were analyzed by the general linear model pipeline of edgeR package in R. Transcriptomes derived from different hosts were compared pairwise; the reference is always the host shown in the right side of the figure. Total differentially expressed genes for each comparison for each condition were subjected to a GO enrichment analysis. Significant GO terms for the given set of genes are shown. Total genes related to a GO term present in the CHA0 genome are given between brackets and the indicated percentage shows how many of those are differentially expressed in each comparison (p value < 0.001). a P. xylostella vs. wheat roots, b G. mellonella hemolymph vs. wheat roots, c P. xylostella vs. G. mellonella hemolymph. BP biological process, MF molecular function. The “Wheat” sample corresponds to wheat-roots 1 week after inoculation, “P. xylostella 24/36 h” to Plutella xylostella 24 and 36 h after oral infection; “G. mellonella” to Galleria mellonella hemolymph 24 h after hemocoel injection.

To successfully reach root zones where exudates are released and to outcompete other organisms, the bacteria need to actively move [49,50,51]. Motor activity-related genes were expressed under all conditions but especially upregulated on wheat roots as shown by clustering, DGE and heatmap analyses (Figs. 2b, 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. S3). This confirms the relevance of flagella for wheat root colonization. Interestingly, the reb genes required for R-body synthesis were upregulated on wheat roots and repressed in both insect compartments (Fig. 4), which supports the lack of differences in insecticidal activity between a ΔrebB1 mutant and wildtype CHA0 in oral and injection assays [16]. R-bodies disrupt membranes and deliver toxins in several bacterial genera including Pseudomonas. In Azorhizobium caulinodans, the R-bodies have also been related to Paramecium killing and cell-disruption in the legume Sesbania rostrata [52,53,54].

Black indicates low expression (less than 10 counts per million reads) and yellow indicates high expression (more than 103 counts per million reads). The “Wheat” sample corresponds to wheat-roots 1 week after inoculation, “P. xylostella 24/36 h” to Plutella xylostella 24 and 36 h after oral infection; “G. mellonella” to Galleria mellonella hemolymph 24 h after hemocoel injection.

Specific activities in the insect gut are related to defense against the host immune system and to competition

The gut is a challenging environment for exogenous bacteria as they have to compete with the resident microflora and to overcome the insect immune response e.g., antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) [55]. The P. xylostella expression profiles reveal upregulation of several genes, which might help CHA0 to cope with these menaces in the gut. The P. xylostella 24 h transcription profile main cluster harbors most of the genes related to amidase activity (Fig. 2). Amidases cleave proteoglycans that trigger host immune response thereby helping bacteria to avoid recognition [55,56,57]. We suggest a similar mechanism in our model. At 36 h after feeding, we found that genes related to the transport of nitrogen and organic substances were specifically upregulated (Fig. 2b, P. xylostella 36 h). This might be related to the use of nitrogenous compounds emerging from the interaction of ROS and RNS during the insect immune response [58]. The combined evidence from the P. xylostella 24/36 h transcriptomic responses compared to wheat root transcriptomes showed upregulation of coding genes related to oxidoreductase activity proteins (Fig. 3a). This could be related to the bacterial defense against ROS produced by the insect host. Among the most upregulated genes in the P. xylostella-wheat comparison, were pap and PPRCHA0_1961 encoding a polyphosphate kinase (PPK) and a predicted “copy-paste” transposase, respectively (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 6). PPKs have been related to motility, quorum sensing, biofilm formation, and virulence of P. aeruginosa and regulation of stress response in Campylobacter jejuni [59,60,61,62,63]. We hypothesize that pap might play a similar role in CHA0 insect pathogenesis. The PPRCHA0_1961-encoded transposase might perform genomic rearrangements which are important for bacterial adaptation and pathogenesis as shown for P. aeruginosa with another transposable element family [64, 65].

The insect immune response also triggers the production of AMPs that kill invasive bacteria [55]. The dominant short O-antigenic polysaccharide (O-PS) encoded by the OSA cluster confers resistance to insect AMPs in CHA0 [33]. This supports invasion competences through oral and systemic insecticidal activity of the bacterium. Of the four CHA0 O-PS clusters [33], OSA and OBC3 (which encodes the major long O-antigen of CHA0) were expressed in all our backgrounds. Interestingly, OBC1 and OBC2 were only expressed in the P. xylostella gut (Supplementary Fig. S3). It remains unknown whether OBC1 and OBC2 might also play a role in avoiding resistance to or recognition by the insect immune system.

In order to persist, attach and breach the gut epithelium, CHA0 must successfully compete against the resident gut bacteria. CHA0 competes in the rhizosphere by producing a variety of antimicrobial compounds, which contribute to rhizosphere competence and the suppression of soilborne pathogens [5]. Among the tested hosts, all of the biosynthetic genes involved in the production of the broad-spectrum antimicrobials hydrogen cyanide, 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol, and pyrrolnitrine were expressed in P. xylostella and expressed at low levels on wheat roots (with the exception of 2,4-diactetylphloroglucinol which was highest expressed on roots), but were not expressed in the G. mellonella hemolymph. Although the expression of hydrogen cyanide is low in our study, it has been previously shown to influence insect survival when CHA0 is injected into the G. mellonella hemocoel [29]. Although the expression of pyoluteorin biosynthetic genes was not detected on the roots of any tested plants [37], they were expressed in P. xylostella (Supplementary Fig. S3). Hence, pyoluteorin might play a more important role in persistence in insect hosts than on plant roots. Combined, our results support that antimicrobials are not only used for competition against microorganisms in the rhizosphere but also during colonization of an insect. We think that the expression of antimicrobials was mainly modulated by the insect background and less by the presence of resident microorganisms in the Plutella gut because the analysis of control larvae revealed a very low microbial background cultivable on LB (Supplementary Fig. S1). Likewise, CHA0 expresses antimicrobials on roots, even in the absence of other microorganisms [37].

The type VI secretion system (T6SS) has been related to pathogenicity and bacterial competition in the insect gut. In CHA0, the vgrG1a and vgrG1b genes encoding distinct T6SS spikes and rhsA and ggh1 encoding respective associated effectors with predicted nuclease activity were demonstrated to contribute to invading P. brassicae. These genes play a role in the ability of CHA0 to compete with the gut microflora and impact on its composition [28]. In our study, these genes were expressed in both insect models (Fig. 4). This underlies the importance of these T6SS components during competitive host invasion [66,67,68]. Interestingly, the expression of vgrG1b and its associated effector gene ggh1 was higher in the P. xylostella gut than in the G. mellonella hemolymph. But we found the opposite for vgrG1a and rhsA (Fig. 4) indicating that T6SS-mediated competition is important not only in the gut but also at a later infection stage in the hemolymph.

Expression patterns of pap, chiD, pltA, and the PPRCHA0_1961 IS3 transposase analyzed by qPCR showed the same tendencies as in the RNA-seq with significant differences between environments (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Functions underlying transmigration from the gut lumen into the hemocoel

In order to transmigrate from the gut to the hemolymph CHA0 needs to overcome several barriers such as the peritrophic matrix and the gut epithelium. Based on the established expression profiles, we propose the following model of the transmigration process.

Orfamide A, the chitinase and the phospholipase C encoded by ofaABC, chiD, and plcN, respectively, showed the highest expression in P. xylostella when compared to the other environments (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S3). In previous studies, CHA0 mutants lacking any of these genes had reduced activity in oral P. xylostella feeding assays, but not upon injection into G. mellonella hemolymph [16, 29]. This suggests that ofaABC, chiD, and plcN are important in the gut infection/transmigration phase. Orfamide A and chitinases were shown to be important in insect pathogenesis even though the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated [29,30,31]. We hypothesize that orfamide A might be important for adsorption to the peritrophic matrix that lines the gut epithelium and the chitinase might create a passage through this chitinous membrane into the mucus layer. The mammal lung and gut mucus layers are rich in phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine, two major components of eukaryotic membranes [69]. Phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylcholine are cleaved by PlcN [70] and used as a nutrient source in P. aeruginosa [71, 72]. Therefore, we propose that the nonhemolytic PlcN phospholipase might release phospholipids from the gut mucus and weaken the enterocyte membranes in insects. At a later stage of infection, Pseudomonas probably use exopolysaccharides to attach to the epithelium as described in chronic lung infections by P. aeruginosa [73,74,75,76] before they transmigrate to the hemocoel. We identified the protein functions associated to alginic acid metabolism and the transport of organic compounds being differentially regulated when comparing P. xylostella to G. mellonella (Fig. 3c) supporting our model. The CHA0 exopolysaccharide gene clusters alg, psl, pga, and pel were barely expressed in the G. mellonella hemolymph but were upregulated on wheat roots and in P. xylostella. This upregulation could play a role in attachment to the insect gut surface (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Once the bacteria have passed through the peritrophic matrix and are attached to the gut, they need to disrupt the epithelial cells to create a passage to the hemocoel. Based on our transcriptomic evidence, we found that TPS systems may be involved in this process. TPS of Gram-negative bacteria consist of a B transporter and an A effector protein, e.g., an adhesin, hemolysin, or exolysin [77]. TPS secreted toxins were identified in different Gram-negative bacteria e.g., in P. aeruginosa, Serratia marcescens, Proteus mirabilis, Haemophilus influenza, and entomopathogenic bacteria such as Photorhabdus luminescens and P. entomophila [77,78,79,80,81,82]. TPS are related to cellular adhesion, pore formation, and competition across bacterial species [77, 83], host tissue damage [84], cell-junctions cleavage in P. aeruginosa PA7 [77, 82, 85], and macrophage pyroptosis in P. aeruginosa PA7, P. entomophila L48, P. putida KT2440, and P. protegens CHA0 by ExlA-like proteins [81].

The CHA0 genome harbors four predicted complete TPS named tpsBA1-4 encoding TpsBA1-4 (Fig. 5; PPRCHA0_0168-169, PPRCHA0_0625-0626, PPRCHA0_1574-1575, and PPRCHA0_4277-4278). TPSA1-4 effector proteins share between 39.3% and 59.5% amino acid identity with the ExlA protein of P. aeruginosa PA7 (Supplementary Table S7). Similarly to PA7, ExlA, and FhaB of Bordetella pertussis, CHA0 TpsA1-4 have a N-terminal TPS domain followed by several copies of filamentous-haemagglutinine domains (FLH1 and 2 domains, Fig. 5) [82, 83]. In addition, TpsA1 also has a pre-toxin VENN domain (Fig. 5a) commonly involved in cell–cell interactions [83, 86]. While the domain structure of TpsA4 is highly similar to PA7 ExlA, TpsA1-3 contain several predicted FLH1 repeats in addition to the FLH2 domains (Fig. 5).

a Domain analysis of the secreted protein with HMMER database comparing Bordetella pertussis protein FhaB, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA7 protein ExlA and P. protegens CHA0 proteins TpsA1, TpsA2, TpsA3, and TpsA4 (PPRCHA0_0168-169, PPRCHA0_0625-0626, PPRCHA0_1574-1575, and PPRCHA0_4277-4278, respectively). The signal peptide and TPS domains are used to interact with the transporter protein for membrane translocation; the filamentous hemagglutinin 1 attaches to the host-cell and the filamentous hemagglutinin 2 translocates the PT-VENN domain into the host; DUF637 is common to hemagglutinins but its function is still unclear [83]. b Heatmap showing the normalized expression values for genes related to the four complete two-partner secretion systems in P. protegens CHA0 colonizing different hosts. The “Wheat” sample corresponds to wheat-roots 1 week after inoculation, “P. xylostella 24/36 h” to Plutella xylostella 24 and 36 h after oral infection, “G. mellonella” to Galleria mellonella hemolymph 24 h after hemocoel injection. c Survival of P. xylostella larvae after exposure to artificial diet pellets spiked with 4 × 106 cells of CHA0 wild type, or its tpsA2 or tpsA4 deletion mutants. Thirty-two 2nd instar larvae were used per bacterial strain. d Survival of G. mellonella larvae after injection of 2 × 103 cells into the hemocoel. Eighteen 7th instar larvae were used per bacterial strain. One experiment of each is shown and two more P. xylostella feeding and one G. mellonella injection are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. Asterisks indicate significant differences of mutants to the wildtype (log-rank test, p value < 0.05).

The four tpsA genes showed very different expression profiles across the examined environments (Fig. 5b). While tpsA2 was equally expressed in all examined hosts, the other three variants were upregulated in insects when compared to wheat roots. tpsA3 was similarly expressed in both insect models, in comparison to tpsA1 which was upregulated during P. xylostella infection and tpsA4 which was highly upregulated in G. mellonella hemolymph. Interestingly, tpsA4 was among the 20 most upregulated genes in G. mellonella when compared to P. xylostella (Supplementary Table S6).

In order to assess the importance of TpsA toxins for insect infection, we tested tpsA knockout mutants in feeding assays with P. xylostella and in injection assays with G. mellonella. The deletion of tpsA4, which was highly expressed in an insect background but not on wheat roots, resulted in significantly reduced insecticidal activity in two out of three feeding experiments. A deletion mutant of tpsA2, which was expressed in all tested hosts, led to significantly reduced insecticidal activity in one out of three feeding experiments (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. S5a, b). In addition, a tpsA4 deletion mutant showed significantly slower mortality when injected into the G. mellonella hemocoel in two experiments (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. S5c). Furthermore, we confirmed the expression patterns of tpsA2 and tpsA4 by qPCR showing the same tendencies as found in the transcriptomic analyses with significant differences between environments (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. S4).

The functions of the CHA0 TPS-secreted toxins are still unknown, but these toxins may play similar roles as the P. aeruginosa toxin ExlA. TpsBA1-3 may be involved in gut colonization, adhesion to tissues, bacterial competition, and the disruption of the gut epithelium. The high expression of TpsBA4 in the hemolymph suggests that the protein could be involved in the defense against insect immune reactions e.g., by triggering hemocyte cell death. Our model of TPS interactions are supported by the findings that CHA0 mutants lacking tpsA4 are largely impaired in macrophage killing [81].

The insect hemocoel is more permissive for rapid proliferation than the gut

During the first phase of gut infection, CHA0 shows limited growth and metabolism. In contrast, we found an upregulation of structural ribosome constituents and nucleic acid synthesis in the G. mellonella hemolymph (Figs. 2b and 3c). The pairwise comparison revealed a general upregulation of genes involved in proliferation and metabolic activities in the G. mellonella hemolymph compared to the P. xylostella gut (Fig. 3c). In contrast, oxidoreductase and catalase activity were downregulated compared to P. xylostella and wheat (Fig. 3c, b). These differences indicate that the hemolymph is a less stressful environment and that CHA0 has enough nutrients allowing rapid proliferation leading to the systemic infection and ultimately death of the insect. However, oxidoreductase functions were upregulated in the G. mellonella hemolymph when compared to the hemolymph mimicking Grace’s Medium (Supplementary Fig. S6 and Table S6). This may be related to defenses against insect immune responses. Furthermore, the bacteria are challenged by iron deprivation forcing a strong upregulation of pyoverdine synthesis and heme-acquisition related genes (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S6). Pathogenic bacteria need siderophores such as pyoverdine and heme-acquisition systems to acquire the essential iron from iron-binding proteins e.g., ferritin or transferrin in the gut lumen, the hemolymph, and the fat body. Also, the hemolymph pH is not acidic enough for the scarce free iron to be bioavailable for the bacteria [87,88,89]. However, mutants defective in pyoverdine production still show insecticidal activity [29], probably because the loss of pyoverdine is compensated by the production of other siderophores e.g., enantio-pyochelin during insect colonization [90, 91].

The Fit insect toxin substantially contributes to insect killing in systemic infections by CHA0 and other P. protegens/P. chlororaphis [15, 17, 20]. It possibly interferes with the activity of hemocytes as was shown for the related apoptotic toxin Mcf of P. luminescens [92, 93]. Previously, Fit was shown to be only produced in the insect hemolymph but not on plant roots using a mCherry-labeled FitD [20]. We can show now that fitD was among the 20 most upregulated genes in the G. mellonella-wheat comparison (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S6). Our study further shows that the maximal expression of fitD occurs in the hemolymph but that the upregulation is initiated when the bacteria colonize the insect gut (Fig. 4).

Genus-wide comparative genomics to retrace the evolutionary origins of Pseudomonas protegens CHA0 pathogenicity factors

We compared the full protein sequence of CHA0 and 96 pseudomonads using ortholog analyses (Supplementary Fig. S7). We analyzed phylogenetic groups harboring strains showing plant beneficial interactions as well as plant-, insect-, and human pathogenic abilities (Supplementary Table S2). P. protegens/P. chlororaphis subgroups possess a set of specific traits absent in other Pseudomonas groups (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. S7). We investigated whether CHA0 genes responding to lifestyle changes were common to other pathogenic and beneficial Pseudomonas. We focussed on genes with host or insect compartment specific expression that have emerged from this study and/or have been shown to contribute to insecticidal activity in earlier studies [16, 28] i.e., specific exoenzymes, exopolysaccharides, T6SS modules, and toxins.

A comparison of the full in silico proteomes of 97 pseudomonads belonging to phylogenetic groups harboring insect pathogenic, human pathogenic, plant pathogenic, and plant beneficial strains (groups and subgroups as defined by Hesse et al. [2]) was performed and is shown in Supplementary Fig. S7. Here, we show the distribution of selected CHA0 traits investigated in this study in ecologically different Pseudomonas strains. Strains with described activity are marked in: pink for insecticidal activity (oral or injectable); dark-blue for human pathogenic activity; orange for plant pathogenic activity; green for plant-beneficial activity (references in Supplementary Table S2). Am. amidases, Enz. enzymes, Trans. transposase.

Some genes with lifestyle specific expression patterns are distinct of the P. protegens subgroup including the transposase PPRCHA0_1961, Vgr1a elements e.g., the Rhsl effector [28] and TpsB1 (Fig. 6). This suggests that these genes were recently acquired by P. protegens or were lost in all other groups. We propose that some of these genes are specific for insect interactions. However, most functions in insecticidal activity are shared by the P. protegens and P. chlororaphis subgroups. Intriguingly, some of these traits are also present in the phylogenetically distant P. aeruginosa group [1, 2] harboring animal and human pathogens. Among these functions, we found a chitinase, the phospholipase PlcN, proteins related to the production of the exopolysaccharide Pel, T6SS components of the Vgr1A and Vgr1b modules, the Reb toxins or some proteins related to stress-response. The presence of these insect interaction-related CHA0 traits in very distant species such as P. aeruginosa (Fig. 6) suggests that either these are ancestral functions and were lost repeatedly during the evolution of Pseudomonas or that they have been independently acquired. Interestingly, the entomopathogen P. entomophila [24] lacks several of the CHA0 functions shared with the aeruginosa group including Pel, Psl, the Vgr1a, and b elements [28], and some stress-related proteins (Fig. 6). P. chlororaphis and P. protegens with the ability to colonize plant and insect environments seem to have a very distinct toolbox when compared to the rest of the analyzed species (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. S7).

Conclusions

P. protegens and P. chlororaphis are bacterial species with multifaceted lifestyles as they can easily switch between plant and insect hosts. Our analyses of the P. protegens CHA0 transcriptomes across plant, insect and specific culture medium conditions significantly enhance our understanding of the shared and specific functions deployed across host-associated lifestyles. We have also shown how different functions are modulated over the course of an insect infection. Our results show that CHA0 deploys distinct toolsets to colonize plant-roots, the insect gut, and the insect hemocoel with specific expression in some environments (e.g., flagella on roots or the Fit toxin in the insect hemocoel). In contrast, we also discovered that antimicrobial metabolites, the T6SS, and exopolysaccharides serve as weapons or colonization factors across multiple environments. We also identified potential new factors involved in insect interactions of P. protegens CHA0 i.e., PPK and the transposase PPRCHA0_1961 and we demonstrated the contribution of TPS systems in insect pathogenicity. Based on the results presented here and our previous studies on insecticidal traits, we propose a comprehensive insect colonization and pathogenesis model for P. protegens CHA0 as summarized in Fig. 7.

In the proposed pathogenesis model, the insect immune response is marked in blue, CHA0 factors emerging from this study in dark green and factors shown to be involved in P. protegens CHA0 insecticidal activity in previous studies in pink. As described previously by Engel and Moran [55], in the event of a pathogen invasion, the insect will detect the presence of proteoglycans or other bacterial components that will trigger the immune response. The gut epithelium activates the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) through the DUOX membrane oxidases and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) through the IMD pathway. If the signal reaches the insect fat body, the Toll pathway will activate the production of AMPs as well [55, 94]. We hypothesize the following infection process: CHA0 is taken up by an insect feeding on plant colonized by the bacterium. In the gut, the bacterium faces the first line of the insect defense and has to compete with the resident microflora. Amidase activity degrading proteoglycan residues from the cell wall helps P. protegens CHA0 to avoid recognition by the immune system. The bacterium further uses oxidoreductases and the Pap protein to protect itself against reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Nitrogen transporters might capture nitrogenous compounds resulting from the interaction of RNS and ROS. In order to better survive this adverse and stressful environment, it is possible that P. protegens CHA0 activates transposases for genomic rearrangements in order to increase its genomic variability. The bacterial cells can resist AMPs thanks to the O-polysaccharide conformation of its surface [33]. CHA0 also produces antimicrobial compounds as shown here and in Flury et al. [29] and it uses the type VI secretion system (T6SS) to fight the microflora of the insect or other ingested bacteria. For breaching the gut epithelium, we propose the following scenario: to adhere to the surface of the peritrophic matrix, CHA0 uses the cyclic lipopeptide surfactant orfamide A [29]. Then, the chitinase disrupts the chitinous peritrophic matrix [16]. P. protegens CHA0 may use the phospholipase PlcN to release nutrients from the mucus layer or to damage the epithelial cells [16, 95] and exopolysaccharides to establish in the epithelium [76]. Subsequently, the production of different two-partner secretion proteins (TPS) triggers host cell death and disrupts the cadherin junctions between epithelial cells. This will allow the bacteria to transmigrate into the hemocoel. Here CHA0 has to resist phagocytosis by granulocytes, encapsulation by plasmatocytes, melanin coating by oenocytoids and AMPs produced by the fat body [21, 96]. To fight the immune cells, CHA0 might use the FitD toxin [33], hydrogen cyanide (HCN) [29], and the TpsA proteins which, in combination with the bacterial multiplication, will finally lead to the death of the insect.

We finally show that some key insect pathogenicity factors are conserved across Pseudomonas groups, while other factors are patchily distributed in P. protegens or P. protegens/chlororaphis suggesting distinct evolutionary origins.

Data availability

The generated RNA-seq datasets were deposited on the NCBI Short Read Archive under the BioProject ID PRJNA595077.

References

Garrido-Sanz D, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Göker M, Martín M, Rivilla R, Redondo-Nieto M. Genomic and genetic diversity within the Pseudomonas fluorescens complex. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0150183.

Hesse C, Schulz F, Bull CT, Shaffer BT, Yan Q, Shapiro N, et al. Genome-based evolutionary history of Pseudomonas spp. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20:2142–59.

Peix A, Ramírez-Bahena M-H, Velázquez E. The current status on the taxonomy of Pseudomonas revisited: An update. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;57:106–16.

Silby MW, Winstanley C, Godfrey SAC, Levy SB, Jackson RW. Pseudomonas genomes: diverse and adaptable. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:652–80.

Haas D, Défago G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:307–19.

Vacheron J, Desbrosses G, Bouffaud M-L, Touraine B, Moënne-Loccoz Y, Muller D, et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and root system functioning. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:1–19.

Pieterse CMJ, Zamioudis C, Berendsen RL, Weller DM, Van Wees SCM, Bakker PAHM. Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2014;52:347–75.

Mauchline TH, Malone JG. Life in earth—the root microbiome to the rescue? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2017;37:23–8.

Berg G. Plant–microbe interactions promoting plant growth and health: perspectives for controlled use of microorganisms in agriculture. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;84:11–18.

Arthurs S, Dara SK. Microbial biopesticides for invertebrate pests and their markets in the United States. J Invertebr Pathol. 2019;165:13–21.

Oerke E-C. Crop losses to pests. J Agric Sci. 2006;144:31–43.

Kumar V, Kumar P. Pesticides in agriculture and environment: impacts on human health. In: Contaminants in agriculture and environment: health risks and remediation. Haridwar, India: Agro Environ Media—Agriculture and Environmental Science Academy; 2019. pp 76–95.

Savary S, Willocquet L, Pethybridge SJ, Esker P, McRoberts N, Nelson A. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat Ecol Evol. 2019;3:430–9.

Loper JE, Hassan KA, Mavrodi DV, Ii EWD, Lim CK, Shaffer BT, et al. Comparative genomics of plant-associated Pseudomonas spp.: insights into diversity and inheritance of traits involved in multitrophic interactions. PLOS Genet. 2012;8:e1002784.

Ruffner B, Péchy‐Tarr M, Ryffel F, Hoegger P, Obrist C, Rindlisbacher A, et al. Oral insecticidal activity of plant-associated pseudomonads. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:751–63.

Flury P, Aellen N, Ruffner B, Péchy-Tarr M, Fataar S, Metla Z, et al. Insect pathogenicity in plant-beneficial pseudomonads: phylogenetic distribution and comparative genomics. ISME J. 2016;10:2527–42.

Péchy-Tarr M, Bruck DJ, Maurhofer M, Fischer E, Vogne C, Henkels MD, et al. Molecular analysis of a novel gene cluster encoding an insect toxin in plant-associated strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:2368–86.

Olcott MH, Henkels MD, Rosen KL, L.Walker F, Sneh B, Loper JE, et al. Lethality and developmental delay in Drosophila melanogaster larvae after ingestion of selected Pseudomonas fluorescens strains. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12504.

Kupferschmied P, Maurhofer M, Keel C. Promise for plant pest control: root-associated pseudomonads with insecticidal activities. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:1–17.

Kupferschmied P, Péchy-Tarr M, Imperiali N, Maurhofer M, Keel C. Domain shuffling in a sensor protein contributed to the evolution of insect pathogenicity in plant-beneficial Pseudomonas protegens. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003964.

Keel C. A look into the toolbox of multi-talents: insect pathogenicity determinants of plant-beneficial pseudomonads. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:3207–9.

Rangel LI, Henkels MD, Shaffer BT, Walker FL, Ii EWD, Stockwell VO, et al. Characterization of toxin complex gene clusters and insect toxicity of bacteria representing four subgroups of Pseudomonas fluorescens. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0161120.

Flury P, Vesga P, Dominguez-Ferreras A, Tinguely C, Ullrich CI, Kleespies RG, et al. Persistence of root-colonizing Pseudomonas protegens in herbivorous insects throughout different developmental stages and dispersal to new host plants. ISME J. 2019;13:860–72.

Vodovar N, Vinals M, Liehl P, Basset A, Degrouard J, Spellman P, et al. Drosophila host defense after oral infection by an entomopathogenic Pseudomonas species. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:11414–9.

Maciel-Vergara G, Jensen AB, Eilenberg J. Cannibalism as a possible entry route for opportunistic pathogenic bacteria to insect hosts, exemplified by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a pathogen of the giant mealworm Zophobas morio. Insects. 2018;9:88–103.

Péchy‐Tarr M, Borel N, Kupferschmied P, Turner V, Binggeli O, Radovanovic D, et al. Control and host-dependent activation of insect toxin expression in a root-associated biocontrol pseudomonad. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:736–50.

Ruffner B, Péchy-Tarr M, Höfte M, Bloemberg G, Grunder J, Keel C, et al. Evolutionary patchwork of an insecticidal toxin shared between plant-associated pseudomonads and the insect pathogens Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:609–23.

Vacheron J, Péchy-Tarr M, Brochet S, Heiman CM, Stojiljkovic M, Maurhofer M, et al. T6SS contributes to gut microbiome invasion and killing of an herbivorous pest insect by plant-beneficial Pseudomonas protegens. ISME J. 2019;13:1318–29.

Flury P, Vesga P, Péchy-Tarr M, Aellen N, Dennert F, Hofer N, et al. Antimicrobial and insecticidal: cyclic lipopeptides and hydrogen cyanide produced by plant-beneficial Pseudomonas strains CHA0, CMR12a, and PCL1391 contribute to insect killing. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–15.

Jang JY, Yang SY, Kim YC, Lee CW, Park MS, Kim JC, et al. Identification of orfamide A as an insecticidal metabolite produced by Pseudomonas protegens F6. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:6786–91.

Loper JE, Henkels MD, Rangel LI, Olcott MH, Walker FL, Bond KL, et al. Rhizoxin analogs, orfamide A and chitinase production contribute to the toxicity of Pseudomonas protegens strain Pf-5 to Drosophila melanogaster. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:3509–21.

Schellenberger U, Oral J, Rosen BA, Wei J-Z, Zhu G, Xie W, et al. A selective insecticidal protein from Pseudomonas for controlling corn rootworms. Science. 2016;354:634–7.

Kupferschmied P, Chai T, Flury P, Blom J, Smits THM, Maurhofer M, et al. Specific surface glycan decorations enable antimicrobial peptide resistance in plant-beneficial pseudomonads with insect-pathogenic properties. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:4265–81.

King EO, Ward MK, Raney DE. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J Lab Clin Med. 1954;44:301–7.

Landa BB, de Werd HAE, McSpadden Gardener BB, Weller DM. Comparison of three methods for monitoring populations of different genotypes of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens in the rhizosphere. Phytopathology. 2002;92:129–37.

Bertani G. Studies on lysogenesis I: the mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1951;62:293–300.

de Werra P, Baehler E, Huser A, Keel C, Maurhofer M. Detection of plant-modulated alterations in antifungal gene expression in Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 on roots by flow cytometry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:1339–49.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20.

Smits THM, Rezzonico F, Frasson D, Vesga P, Vacheron J, Blom J, et al. Updated genome sequence and annotation for the full genome of Pseudomonas protegens CHA0. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2019;8:e01002–19.

Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21.

Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–30.

Robinson MD, Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R25.

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–40.

McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4288–97.

Jones P, Binns D, Chang H-Y, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–40.

Carlson M. GO.db: A set of annotation maps describing the entire Gene Ontology. R package version. 3.8.2. 2019. https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/annotation/html/GO.db.html.

Falcon S, Gentleman R. Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:257–8.

Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16:157–71.

Huang X-F, Chaparro JM, Reardon KF, Zhang R, Shen Q, Vivanco JM. Rhizosphere interactions: root exudates, microbes, and microbial communities. Botany. 2014;92:267–75.

Benizri E, Baudoin E, Guckert A. Root colonization by inoculated plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 2001;11:557–74.

Barahona E, Navazo A, Martínez-Granero F, Zea-Bonilla T, Pérez-Jiménez RM, Martín M, et al. Pseudomonas fluorescens F113 mutant with enhanced competitive colonization ability and improved biocontrol activity against fungal root pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:5412–9.

Raymann K, Bobay L-M, Doak TG, Lynch M, Gribaldo S. A genomic survey of Reb homologs suggests widespread occurrence of R-Bodies in proteobacteria. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2013;3:505–16.

Polka JK, Silver PA. A tunable protein piston that breaks membranes to release encapsulated cargo. ACS Synth Biol. 2016;5:303–11.

Matsuoka J, Ishizuna F, Kurumisawa K, Morohashi K, Ogawa T, Hidaka M, et al. Stringent expression control of pathogenic R-body production in legume symbiont Azorhizobium caulinodans. mBio. 2017;8:e00715–17.

Engel P, Moran NA. The gut microbiota of insects—diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:699–735.

Humann J, Lenz LL. Bacterial peptidoglycan-degrading enzymes and their impact on host muropeptide detection. J Innate Immun. 2009;1:88–97.

Atilano ML, Pereira PM, Vaz F, Catalão MJ, Reed P, Grilo IR, et al. Bacterial autolysins trim cell surface peptidoglycan to prevent detection by the Drosophila innate immune system. eLife; 3:e02277.

Fang FC. Antimicrobial reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: concepts and controversies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:820–32.

Rashid MH, Rao NN, Kornberg A. Inorganic polyphosphate is required for motility of bacterial pathogens. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:225–7.

Rashid MH, Rumbaugh K, Passador L, Davies DG, Hamood AN, Iglewski BH, et al. Polyphosphate kinase is essential for biofilm development, quorum sensing, and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:9636–41.

Zhang H, Ishige K, Kornberg A. A polyphosphate kinase (PPK2) widely conserved in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16678–83.

Chandrashekhar K, Kassem II, Nislow C, Gangaiah D, Candelero-Rueda RA, Rajashekara G. Transcriptome analysis of Campylobacter jejuni polyphosphate kinase (ppk1 and ppk2) mutants. Virulence. 2015;6:814–8.

Gangaiah D, Liu Z, Arcos J, Kassem II, Sanad Y, Torrelles JB, et al. Polyphosphate kinase 2: a novel determinant of stress responses and pathogenesis in Campylobacter jejuni. PLOS ONE. 2010;5:e12142.

Vandecraen J, Chandler M, Aertsen A, Van Houdt R. The impact of insertion sequences on bacterial genome plasticity and adaptability. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2017;43:709–30.

Obi CC, Vayla S, de Gannes V, Berres ME, Walker J, Pavelec D, et al. The integrative conjugative element cIc (ICEcIc) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa JB2. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1532.

Fu Y, Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. Tn-seq analysis of vibrio cholerae intestinal colonization reveals a role for T6SS-mediated antibacterial activity in the host. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:652–63.

Hachani A, Wood TE, Filloux A. Type VI secretion and anti-host effectors. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;29:81–93.

Chen C, Yang X, Shen X. Confirmed and potential roles of bacterial T6SSs in the intestinal ecosystem. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1484.

Braun A, Treede I, Gotthardt D, Tietje A, Zahn A, Ruhwald R, et al. Alterations of phospholipid concentration and species composition of the intestinal mucus barrier in ulcerative colitis: a clue to pathogenesis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1705–20.

Ostroff RM, Vasil AI, Vasil ML. Molecular comparison of a nonhemolytic and a hemolytic phospholipase C from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5915–23.

Vasil ML. Pseudomonas aeruginosa phospholipases and phospholipids. In: Ramos J-L, Levesque RC, editors. Pseudomonas. Springer: US; 2006. pp. 69–97.

Titball RW. Bacterial phospholipases. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;84:127S–137S.

Laverty G, Gorman SP, Gilmore BF. Biomolecular mechanisms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli biofilm formation. Pathogens. 2014;3:596–632.

Jones CJ, Wozniak DJ. Psl produced by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa contributes to the establishment of biofilms and immune evasion. mBio. 2017;8:e00864–17.

Valentini M, Gonzalez D, Mavridou DA, Filloux A. Lifestyle transitions and adaptive pathogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2018;41:15–20.

Skariyachan S, Sridhar VS, Packirisamy S, Kumargowda ST, Challapilli SB. Recent perspectives on the molecular basis of biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and approaches for treatment and biofilm dispersal. Folia Microbiol. 2018;63:413–32.

Guérin J, Bigot S, Schneider R, Buchanan SK, Jacob-Dubuisson F. Two-partner secretion: combining efficiency and simplicity in the secretion of large proteins for bacteria-host and bacteria-bacteria interactions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:148.

Hertle R, Hilger M, Weingardt-Kocher S, Walev I. Cytotoxic action of Serratia marcescens hemolysin on human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:817–25.

Brillard J, Duchaud E, Boemare N, Kunst F, Givaudan A. The PhlA hemolysin from the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens belongs to the two-partner secretion family of hemolysins. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:3871–8.

Elsen S, Huber P, Bouillot S, Couté Y, Fournier P, Dubois Y, et al. A type III secretion negative clinical strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa employs a two-partner secreted exolysin to induce hemorrhagic pneumonia. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:164–76.

Basso P, Wallet P, Elsen S, Soleilhac E, Henry T, Faudry E, et al. Multiple Pseudomonas species secrete exolysin‐like toxins and provoke Caspase‐1‐dependent macrophage death. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19:4045–64.

Reboud E, Basso P, Maillard A, Huber P, Attrée I. Exolysin shapes the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa clonal outliers. Toxins. 2017;9:364–76.

Allen JP, Hauser AR. Diversity of contact-dependent growth inhibition systems of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2019;201:e00776–18.

Melvin JA, Gaston JR, Phillips SN, Springer MJ, Marshall CW, Shanks RMQ, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa contact-dependent growth inhibition plays dual role in host-pathogen interactions. mSphere. 2017;2:e00336–17.

Reboud E, Bouillot S, Patot S, Béganton B, Attrée I, Huber P. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExlA and Serratia marcescens ShlA trigger cadherin cleavage by promoting calcium influx and ADAM10 activation. PLOS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006579.

Zhang D, Iyer LM, Aravind L. A novel immunity system for bacterial nucleic acid degrading toxins and its recruitment in various eukaryotic and DNA viral systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4532–52.

Ma L, Terwilliger A, Maresso AW. Iron and zinc exploitation during bacterial pathogenesis. Metallomics. 2015;7:1541–54.

Tang X, Zhou B. Iron homeostasis in insects: Insights from Drosophila studies. IUBMB Life. 2013;65:863–72.

Cornelis P, Dingemans J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa adapts its iron uptake strategies in function of the type of infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:3–75.

Maurhofer M, Reimmann C, Schmidli-Sacherer P, Heeb S, Haas D, Défago G. Salicylic acid biosynthetic genes expressed in Pseudomonas fluorescens Strain P3 improve the induction of systemic resistance in tobacco against tobacco necrosis virus. Phytopathology. 1998;88:678–84.

Youard ZA, Mislin GLA, Majcherczyk PA, Schalk IJ, Reimmann C. Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 produces enantio-pyochelin, the optical antipode of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa siderophore pyochelin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35546–53.

Daborn PJ, Waterfield N, Silva CP, Au CPY, Sharma S, ffrench-Constant RH. A single Photorhabdus gene, makes caterpillars floppy (mcf), allows Escherichia coli to persist within and kill insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:10742–7.

Vlisidou I, Dowling AJ, Evans IR, Waterfield N, ffrench-Constant RH, Wood W. Drosophila embryos as model systems for monitoring bacterial infection in real time. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000518.

Buchon N, Silverman N, Cherry S. Immunity in Drosophila melanogaster—from microbial recognition to whole-organism physiology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:796–810.

Korbsrisate S, Tomaras AP, Damnin S, Ckumdee J, Srinon V, Lengwehasatit I, et al. Characterization of two distinct phospholipase C enzymes from Burkholderia pseudomallei. Microbiology. 2007;153:1907–15.

Hillyer JF. Insect immunology and hematopoiesis. Dev Comp Immunol. 2016;58:102–18.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Oliver Kindler from Syngenta Crop Protection for providing insect material. We thank Maria Péchy-Tarr for the generation of the TPS mutant strains, Camille Tinguely for her help in the plant assays and Emanuel Kopp, Florence Gilleron, Caroline Meier, and María Péchy-Tarr for their assistance with the insect assays. The quantitative PCR experiments and analysis were performed in collaboration with the Genetic Diversity Centre (GDC), ETH Zurich. Lastly, we would like to thank Simone Fouché for her valuable comments on this paper. Open Access funding provided by ETH Zurich.

Funding

This study was financed by the Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research SNSF (grant numbers 31003A_159520 and 406840_161904).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vesga, P., Flury, P., Vacheron, J. et al. Transcriptome plasticity underlying plant root colonization and insect invasion by Pseudomonas protegens. ISME J 14, 2766–2782 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-0729-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-0729-9

This article is cited by

-

Relation of pest insect-killing and soilborne pathogen-inhibition abilities to species diversification in environmental Pseudomonas protegens

The ISME Journal (2023)

-

Host-adaptive traits in the plant-colonizing Pseudomonas donghuensis P482 revealed by transcriptomic responses to exudates of tomato and maize

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Molecular bases for the stronger plastic response to high nitrate in the invasive plant Xanthium strumarium compared with its native congener

Planta (2023)

-

Pseudomonas protegens Affects Mosquito Survival and Development

Current Microbiology (2023)

-

When Competitors Join Forces: Consortia of Entomopathogenic Microorganisms Increase Killing Speed and Mortality in Leaf- and Root-Feeding Insect Hosts

Microbial Ecology (2023)