Abstract

Diverse aerobic bacteria persist by consuming atmospheric hydrogen (H2) using group 1h [NiFe]-hydrogenases. However, other hydrogenase classes are also distributed in aerobes, including the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase. Based on studies focused on Cyanobacteria, the reported physiological role of the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase is to recycle H2 produced by nitrogenase. However, given this hydrogenase is also present in various heterotrophs and lithoautotrophs lacking nitrogenases, it may play a wider role in bacterial metabolism. Here we investigated the role of this enzyme in three species from different phylogenetic lineages and ecological niches: Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (phylum Proteobacteria), Chloroflexus aggregans (phylum Chloroflexota), and Gemmatimonas aurantiaca (phylum Gemmatimonadota). qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase of all three species is significantly upregulated during exponential growth compared to stationary phase, in contrast to the profile of the persistence-linked group 1h [NiFe]-hydrogenase. Whole-cell biochemical assays confirmed that all three strains aerobically respire H2 to sub-atmospheric levels, and oxidation rates were much higher during growth. Moreover, the oxidation of H2 supported mixotrophic growth of the carbon-fixing strains C. aggregans and A. ferrooxidans. Finally, we used phylogenomic analyses to show that this hydrogenase is widely distributed and is encoded by 13 bacterial phyla. These findings challenge the current persistence-centric model of the physiological role of atmospheric H2 oxidation and extend this process to two more phyla, Proteobacteria and Gemmatimonadota. In turn, these findings have broader relevance for understanding how bacteria conserve energy in different environments and control the biogeochemical cycling of atmospheric trace gases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aerobic bacteria mediate the biogeochemically and ecologically important process of atmospheric hydrogen (H2) oxidation [1]. Terrestrial bacteria constitute the largest sink of this gas and mediate the net consumption of ~70 million tonnes of atmospheric H2 per year [2, 3]. The energy derived from this process appears to be critical for sustaining the productivity and biodiversity of ecosystems with low organic carbon inputs [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Atmospheric H2 oxidation is thought to be primarily mediated by group 1h [NiFe]-hydrogenases, a specialised oxygen-tolerant, high-affinity class of hydrogenases [4, 10,11,12,13]. To date, aerobic heterotrophic bacteria from four distinct bacterial phyla, the Actinobacteriota (formerly Actinobacteria; [10, 12, 14, 15]), Acidobacteriota (formerly Acidobacteria; [16, 17]), Chloroflexota (formerly Chloroflexi; [18]), and Verrucomicrobiota (formerly Verrucomicrobia; [19]), have been experimentally shown to consume atmospheric H2 using this enzyme. This process has been primarily linked to energy conservation during persistence. Reflecting this, the expression and activity of the group 1h hydrogenase is induced by carbon starvation across a wide range of species [10, 12, 16, 18, 20,21,22]. Moreover, genetic deletion of hydrogenase structural genes results in impaired long-term survival of Mycobacterium smegmatis cells and Streptomyces avermitilis spores [20, 21, 23, 24].

Genomic and metagenomic surveys have suggested that other uptake hydrogenases are widely distributed among aerobic bacteria and potentially have a role in atmospheric H2 uptake [4, 25]. These include the widely distributed group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases. This hydrogenase class has primarily been investigated in Cyanobacteria, where it is encoded by most diazotrophic strains; the enzyme recycles H2 released as a by-product of the nitrogenase reaction and inputs the derived electrons into the respiratory chain [26,27,28,29]. However, according to HydDB, group 2a hydrogenases are also encoded by isolates from at least eight other phyla [25], spanning both obligate organoheterotrophs (e.g., Mycobacterium, Runella, Gemmatimonas) and obligate lithoautotrophs (e.g., Acidithiobacillus, Nitrospira, Hydrogenobacter) [12, 30, 31]. In M. smegmatis, this enzyme has a sufficiently high apparent affinity to oxidise H2 even at sub-atmospheric levels [12, 22] and is maximally expressed during transitions between growth and persistence [22, 32]. In common with the group 1h hydrogenase also encoded by this bacterium, the group 2a hydrogenase requires potential electron-relaying iron-sulphur proteins for activity [33] and is obligately linked to the aerobic respiratory chain [22]. However, it remains unclear if atmospheric H2 oxidation by the group 2a hydrogenase reflects a general feature of the enzyme or instead is a specific adaptation of the mycobacterial respiratory chain.

In this study, we investigated whether group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases play a general role in atmospheric H2 consumption. To do so, we studied this enzyme in three species, Gemmatimonas aurantiaca, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, and Chloroflexus aggregans, that differ in their phylogenetic affiliation, ecological niches, and metabolic strategies. The obligate chemoorganoheterotroph G. aurantiaca (phylum Gemmatimonadota; formerly Gemmatimonadetes) was originally isolated from a wastewater treatment plant and to date has not been shown to utilise H2 [34, 35]. The obligate chemolithoautotroph A. ferrooxidans (phylum Proteobacteria) was originally isolated from acidic coal mine effluent, and has been extensively studied for its energetic flexibility, including the ability to grow exclusively on H2 [31, 36, 37]. The metabolically flexible C. aggregans (phylum Chloroflexota), a facultative chemolithoautotroph and anoxygenic photoheterotroph, was originally isolated from a Japanese hot spring and is capable of hydrogenotrophic growth [38,39,40]. The organisms differ in their carbon dioxide fixation pathways, with A. ferrooxidans mediating the Calvin-Benson cycle via two RuBisCO enzymes, C. aggregans encoding the 3-hydroxypropionate cycle [37, 41, 42], and G. aurantiaca unable to fix carbon dioxide [34]. While all three species have previously been shown to encode group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases [4, 37], it is unknown whether they can oxidise atmospheric H2. To resolve this, we investigated the expression, activity, and role of this enzyme in axenic cultures of the three species.

Materials and methods

Bacterial growth conditions

Gemmatimonas aurantiaca (DSM 14586), Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (DSM 14882), and Chloroflexus aggregans (DSM 9486) were imported from DSMZ. All cultures were maintained in 120 mL glass serum vials containing a headspace of ambient air (H2 mixing ratio ~0.5 ppmv) sealed with lab-grade butyl rubber stoppers. Prior to use, stoppers were treated to prevent H2 release by boiling twice in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide for 2 h, and twice in deionised water for 2 h, prior to baking in a 70 °C overnight. Broth cultures of G. aurantiaca were grown in 30 mL of NM1 media as previously described [43] and incubated at 30 °C at an agitation speed of 180 rpm in a New Brunswick Scientific Excella E24 incubator. Cultures of C. aggregans were maintained chemoheterotrophically in 30 mL of 1/5 PE media, as previously described [38], and incubated at 55 °C at an agitation speed of 150 rpm in an Eppendorf 40 Incubator in the dark. Cultures of A. ferrooxidans were maintained in 30 mL DSMZ medium 882 supplemented with an additional 13 g L−1 of FeSO4.7H2O (pH 1.2) and incubated at 30 °C at an agitation speed of 180 rpm in a New Brunswick Scientific Excella E24 incubator. To assess whether bacterial growth was enhanced by the presence of H2 for each species, ambient air headspaces were amended with either 1 or 10% H2 (via 99.999% pure H2 gas cylinder). Growth was monitored by determining the optical density (OD600) of periodically sampled 1 mL extracts using an Eppendorf BioSpectrophotometer.

RNA extraction

Triplicate 30 mL cultures of G. aurantiaca, A. ferrooxidans and C. aggregans were grown synchronously in 120 mL sealed serum vials. Whereas one set of triplicate cultures were grown in an ambient air headspace, another set was grown in an ambient air headspace supplemented with H2 to a final concentration of 10% v/v (via a 99.999% pure H2 cylinder). Cultures were grown to either exponential phase (OD600 0.05 for G. aurantiaca; OD600 0.1 for C. aggregans; OD600 0.05 for A. ferrooxidans) or stationary phase (Day 10 for G. aurantiaca; Day 4 for C. aggregans; Day 14 for A. ferrooxidans). For G. aurantiaca and C. aggregans, cells were then quenched using a glycerol-saline solution (−20 °C, 3:2 v/v), harvested by centrifugation (20,000 × g, 30 min, −9 °C), resuspended in 1 mL cold 1:1 glycerol:saline solution (−20 °C), and further centrifuged (20,000 × g, 30 min, −9 °C). Briefly, resultant cell pellets were resuspended in 1 mL TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), mixed with 0.1 mm zircon beads (0.3 g), and subject to beat-beating (five cycles, 4000 rpm, 30 s) in a Mini-Beadbeater 96 (Biospec) prior to centrifugation (12,000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C). Total RNA was extracted using the phenol-chloroform method as per manufacturer’s instructions (TRIzol Reagent User Guide, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. RNA was treated using the TURBO DNA-free kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per manufacturer’s instructions. RNA from A. ferrooxidans was extracted using a previously described extraction method optimised for acid mine drainage microorganisms [44]. RNA concentration and purity were confirmed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to determine the expression profile of all hydrogenase genes present in each species during different growth phases with and without supplemental H2. cDNA was synthesised using a SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System kit for qRT-PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with random hexamer primers, as per manufacturer’s instructions. For all three species, the catalytic subunit gene of the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase (hucL) was targeted. In addition, transcript levels of the catalytic subunit of all additional [NiFe]-hydrogenases present in these strains were analysed, i.e., group 3d (hoxH) for C. aggregans and both group 1e (hyiB) and group 3b (hyhL) for A. ferrooxidans. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using a LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche) as per manufacturer’s instructions in 96-well plates and conducted in a LightCycler 480 Instrument II (Roche). Primers used in the study (Table S1) were designed using Primer3 [45]. Copy numbers of each gene were interpolated from standard curves of each gene created from threshold cycle (CT) values of amplicons that were serially diluted from 108 to 10 copies (R2 > 0.95). Hydrogenase expression data were then normalised to housekeeping genes in exponential phase under ambient air conditions for each species (16 S rRNA gene for G. aurantiaca and C. aggregans; DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta gene rpoC for A. ferrooxidans). All biological triplicate samples, standards, and negative controls were run in technical duplicate.

Gas chromatography

Gas chromatography measurements were used to determine the capacity of the three species to use sub-atmospheric concentrations of H2. For initial experiments, H2 consumption by triplicate cultures in vials containing an ambient air headspace was monitored during growth; H2 mixing ratios were measured immediately following inoculation (mixing ratio = 440 ± 34 ppbv), then at mid-exponential and late stationary phase. In subsequent experiments, to determine H2 oxidation rate constants, biological triplicate cultures of each species were opened, equilibrated with ambient air (1 h), and resealed. These re-aerated vials were then amended with H2 (via 1% v/v H2 in N2 gas cylinder, 99.999% pure) to achieve final headspace concentrations of ~10 ppmv. Headspace mixing ratios were measured immediately after closure and at regular intervals thereafter for 200 h or until the limit of quantification of the gas chromatograph was reached (42 ppbv H2). This analysis was performed for both exponential phase and stationary phase cultures. For H2 quantification, 2 mL headspace samples were measured using a pulsed discharge helium ionisation detector (model TGA-6791-W-4U-2, Valco Instruments Company Inc.) calibrated against standard H2 gas mixtures of known concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 20, 50, 100, 150, 500, 1000, 2500, 5000, and 7000 ppmv), prepared by diluting either 99.999% pure H2 gas cylinder in synthetic air (20.5% v/v O2 in N2) or 1% v/v H2 in N2 gas into He (99.999% pure) as described previously [18]. The vials for each species were maintained at their respective growth temperatures and agitation speeds for the entire incubation period to facilitate H2 and O2 transfer between the headspace and the culture. Concurrently, headspace mixing ratios from media-only negative controls (30 mL of media for each species) were measured to confirm that observed decreases in gas concentrations were biological in nature. First order rate constants (k values) for exponential and stationary phase H2 consumption were determined using the exponential function in GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.2).

Phylogenetic analysis

A phylogenetic tree was constructed to investigate the distribution and evolutionary history of group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases across bacterial phyla. Amino acid sequences of the catalytic subunit of the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase (HucL) and related enzymes were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Reference Sequence database by protein BLAST in February 2020. The resultant sequences were then classified using HydDB [25], with sequences matching group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases retained and any duplicate and multispecies sequences removed. The 207 amino acid sequences representative of genus-level diversity were aligned with reference sequences using Clustal W in MEGA X [46]. Evolutionary relationships were visualised by constructing a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree, with Neighbour-Joining and BioNJ algorithms applied to a matrix of pairwise distances that were estimated using a JTT model and topology selected by superior log-likelihood value. Gaps were treated with partial deletion, the tree was bootstrapped with 500 replicates, and the tree was midpoint rooted. Sequences used in this analysis are listed in Table S2. In addition, 20 annotated reference genomes (representative of order-level diversity) were retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database and manually analysed for putative group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase gene clusters. The web-based software Properon (doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3519494) was used to generate to-scale gene organisation diagrams of these group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases. All species names and taxonomic assignments follow the Genome Taxonomy Database [47, 48].

Results

The expression profile of group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases is antithetical to group 1h [NiFe]-hydrogenases

We used qRT-PCR to quantify the expression of the large subunit of the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase (hucL). The gene was expressed at moderate to high levels in all three strains during aerobic growth on preferred energy sources (organic carbon for G. aurantiaca and C. aggregans, ferrous iron for A. ferrooxidans) (Fig. 1). Expression levels did not significantly differ between strains grown in an ambient air headspace containing atmospheric H2 or supplemented with 10% H2 (Fig. 1). This suggests hydrogenase expression is constitutive and occurs even when atmospheric concentrations of the substrate are available.

The normalised transcript copy number of the large subunit gene (hucL) are plotted for (a) Gemmatimonas aurantiaca (locus GAU_0412), (b) Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (locus AFE_0702), and (c) Chloroflexus aggregans (locus CAGG_0471). Copy number was analysed by qRT-PCR in cultures harvested during exponential phase and stationary phase, in the presence of either ambient H2 or 10% H2. Error bars show standard deviations of three biological replicates (averaged from two technical duplicates) per condition. Values denoted by different letters were determined to be statistically significant based on a one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison (p < 0.05).

Across all three strains, hydrogenase expression significantly decreased during the transition from growth to persistence. For G. aurantiaca, high expression was observed during exponential phase under both H2-supplemented and H2-unamended conditions (av. 8.4 × 106 copies per gdw) and decreased 51-fold during stationary phase (av. 1.6 × 105 copies gdw−1; p = 0.012) (Fig. 1a). Hydrogenase expression of A. ferrooxidans was moderate during growth (av. 1.8 × 106 copies per gdw) and dropped 3.9-fold in stationary phase cultures (av. 4.5 × 105 copies per gdw; p = 0.013) (Fig. 1b), whereas expression in C. aggregans was very high during exponential growth (av. 2.9 × 109 copies gdw−1) and fell 15,000-fold during persistence (av. 1.9 × 105 copies gdw−1; 0.003) (Fig. 1c). Overall, while expression levels greatly vary between species, these results clearly show the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase is expressed primarily in growing cells. These expression profiles contrast with the group 1h [NiFe]-hydrogenase, which is induced during long-term persistence in a range of species [10, 16, 18, 20,21,22].

Group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases oxidise H2 to sub-atmospheric levels

Hydrogenase activity of the three strains was inferred from monitoring changes in headspace H2 mixing ratios over time by gas chromatography. In line with the expression profiles (Fig. 1), we observed that all three strains oxidised atmospheric H2 during growth in an ambient air headspace (Fig. S1). These observations extend the trait of trace gas scavenging to three more species and suggest that group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases broadly have the capacity to oxidise H2 at atmospheric levels.

We subsequently monitored the consumption of H2 by exponential and stationary phase cultures in ambient air supplemented with 10 ppmv H2. For G. aurantiaca and A. ferrooxidans, H2 was oxidised to sub-atmospheric levels under both conditions in an apparent first-order kinetic process (Fig. 2a, b). However, biomass-normalised first-order rate constants were higher in exponential than stationary phase cells by 23-fold (p = 0.0029) and 120-fold (p < 0.0001), respectively (Fig. 2d). For C. aggregans, H2 was oxidised at rapid rates in exponentially growing cells, but occurred at extremely slow rates in stationary cells (Fig. 2c, d). These observations support the qRT-PCR results by showing hydrogenase activity predominantly occurs during growth. It should be noted that additional [NiFe]-hydrogenases are encoded by both C. aggregans (group 3d) and A. ferrooxidans (group 1e and 3b), but not for G. aurantiaca. These additional hydrogenases are expressed at tenfold lower levels for C. aggregans, but at similar levels for A. ferrooxidans, and hence may contribute to H2 uptake (Fig. S2). It is nevertheless likely that the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases mediate atmospheric H2 uptake given (i) the H2 uptake activities of C. aggregans and A. ferrooxidans mimic that of G. aurantiaca, which lacks additional hydrogenases; (ii) previous genetic studies show group 2a enzymes mediate high-affinity aerobic H2 uptake in mycobacteria [12, 22]; and (iii) group 1e and 3b/3d enzymes are likely incapable of atmospheric H2 oxidation given their respective characterised roles in anaerobic respiration and fermentation [25].

H2 oxidation by cultures of (a) Gemmatimonas aurantiaca, (b) Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, and (c) Chloroflexus aggregans. Error bars show the standard deviation of three biological replicates, with media-only vials monitored as negative controls. Dotted lines show the atmospheric concentration of hydrogen (0.53 ppmv). d Biomass-normalised first-order rate constants based on H2 oxidation observed in exponential and stationary phase cultures. Error bars show standard deviations of three biological replicates and statistical significance was tested using a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison (**= p < 0.01; ****= p < 0.0001).

H2 consumption enhances mixotrophic growth in carbon-fixing strains

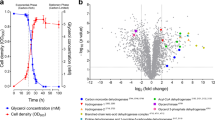

The observation that expression and activity of the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase is optimal during growth suggests this enzyme supports mixotrophic growth. To test this, we monitored growth by optical density of the three strains in headspaces containing H2 at either ambient, 1%, or 10% mixing ratios. No growth differences in the obligate heterotroph G. aurantiaca were observed between the conditions (p = 0.30) (Fig. 3a). In contrast, H2-dependent growth stimulation was observed for the obligate autotroph A. ferrooxidans (1.4-fold increase; p = 0.0003) (Fig. 3b) and facultative autotroph C. aurantiaca (1.2-fold increase; p = 0.029) (Fig. 3c). This suggests that reductant derived from H2 oxidation can be used by these bacteria to fix CO2 through the Calvin-Benson and 3-hydroxypropionate cycles, respectively.

The final growth yield (OD600) of (a) Gemmatimonas aurantiaca, (b) Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, and (c) Chloroflexus aggregans is shown in ambient air vials containing H2 at either ambient, 1%, or 10% concentrations. Error bars show the standard deviation of three biological replicates and statistical significance was tested using a one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison (*= p < 0.05; **= p < 0.01; ***= p < 0.001).

Hydrogenases with common phylogeny and genetic organisation are widely distributed across 13 bacterial phyla

Finally, we surveyed the distribution of group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases to infer which other bacteria may oxidise atmospheric H2. We detected the large subunit of this hydrogenase (HucL) across 171 genera and 13 phyla (Table S2; Fig. S3); this constitutes a 3.2-fold increase in the number of genera and 1.4-fold increase in the number of phyla previously reported to encode this enzyme [4, 25]. This increase in HucL distribution is due to the increase in available genome sequences since previous analyses were performed. The HucL-encoding bacteria include various known hydrogenotrophic aerobes, such as Nitrospira moscoviensis (Nitrospirota) [30], Hydrogenobacter thermophilus (Aquificota) [49], Kyrpidia tusciae (Firmicutes) [50, 51], Sulfobacillus acidophilus (Firmicutes) [52], and Pseudonocardia dioxanivorans (Actinobacteriota) [53], suggesting these strains may also consume atmospheric H2. The hydrogenase was also distributed in various lineages of Bacteroidota, Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, and Deinococcota for which H2 oxidation has not, to our knowledge, been reported.

A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree showed the retrieved HucL sequences form a well-supported monophyletic clade. Most sequences clustered into four major radiations, Bacteroidota-associated, Cyanobacteria-associated, Proteobacteria-associated (including A. ferrooxidans), and a mixed clade containing sequences from seven phyla (including G. aurantiaca and C. aggregans) (Fig. 4). Several genes were commonly genomically associated with hucL genes in putative operons, including the hydrogenase small subunit (hucS), a Rieske-type iron-sulphur protein (hucE) [33], hypothetical proteins (including NHL-repeat proteins) [32], and various maturation factors (Fig. S4). The group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases are distinct in both phylogeny and genetic organisation to the two most closely related hydrogenase subgroups, the previously described group 2e [NiFe]-hydrogenases of aerobic hydrogenotrophic Crenarchaeota [25, 54] and the novel group 2f [NiFe]-hydrogenases that are distributed sporadically in bacteria and archaea (Fig. 4).

Amino acid sequences of the catalytic subunit of the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase (hucL) are shown for 171 bacterial genera. The taxon names of the three study species, G. aurantiaca, A. ferrooxidans, and C. aggregans, are coloured in blue. The tree was constructed using the maximum-likelihood method (gaps treated with partial deletion), bootstrapped with 500 replicates, and rooted at the mid-point. Accession numbers and amino acid sequences used to construct the tree are listed in Table S2. The total number of genomes identified per phylum are as follows: Acidobacteriota (1), Actinobacteriota (27), Aquificota (4), Bacteroidota (34), Chloroflexota (5), Cyanobacteria (61), Deinococcota (2), Firmicutes (19), Gemmatimonadota (1), Myxococcota (1), Nitrospirota (2), Planctomycetota (1), Proteobacteria (49).

Discussion

Overall, these findings demonstrate that atmospheric H2 oxidation is not solely a persistence-linked trait. We infer that group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenases are optimally expressed and active during exponential phase, consume H2 at sub-atmospheric concentrations, and support mixotrophic growth. Largely concordant findings were made in three phylogenetically, physiologically, and ecologically distinct bacterial species. These findings contrast with multiple pure culture studies that have linked expression, activity, and phenotypes associated with group 1h [NiFe]-hydrogenases to survival rather than growth [10, 12, 16, 18, 20, 23, 24]. However, a growth-supporting role of atmospheric H2 oxidation is nevertheless consistent with several surprising recent reports: the measurement of atmospheric H2 oxidation during growth of several strains [12, 19, 23, 55]; the discovery of an Antarctic desert community driven by trace gas oxidation [9]; and the isolation of a proteobacterial methanotroph thought to grow on air alone [56]. Together, these findings suggest that the current persistence-centric model of atmospheric H2 utilisation is overly generalised and that this process also supports mixotrophic growth.

Atmospheric H2 oxidation during growth is likely to primarily benefit bacteria that adopt a mixotrophic lifestyle. While atmospheric H2 alone can sustain bacterial maintenance, theoretical modelling suggests this energy source is insufficiently concentrated to permit growth as the sole energy source [1, 57]. Instead, bacteria that co-oxidise this dependable gas with other organic or inorganic energy sources may have significant selective advantages, especially in environments where resource availability is very low or variable. Likewise, it is probable that many bacteria in natural environments supplement growth by taking advantage of transient increases in H2 availability. For example, the metabolic generalist C. aggregans may facilitate its expansion in geothermal mats by simultaneously utilising geothermal and atmospheric sources of H2, in addition to sunlight and organic compounds [38, 39, 58]. Similarly, in the dynamic environment of wastewater treatment plants, G. aurantiaca may be well-suited to take advantage of fermentatively-produced H2 released during transitions between oxic and anoxic states [35, 59].

The ability to consume atmospheric H2 may also be particularly advantageous during early stages of ecological succession. Indeed, A. ferrooxidans may initially rely on this atmospheric energy source as it colonises barren tailings and establishes an acidic microenvironment conducive for iron oxidation [60]. Hydrogen synthesis in tailings can further benefit A. ferrooxidans as acid conditions and more complex bacterial consortia develop. Specifically, acetate-dependent growth of dissimilatory sulphate reducing bacteria in tailings [58] will initiate endogenous geochemical production of trace hydrogen (FeS + H2S → FeS2 + H2). As tailings cycle between aerobic (vadose) and anaerobic (water-saturating) conditions, the H2 available from atmospheric and geochemical sources respectively may provide a continuous energy source for A. ferrooxidans. In addition, any environments possessing sulphate and iron, i.e., “downstream” from acid-generating ecosystems (including marine sediments), can generate hydrogen through bacterial organotrophic sulphate reduction.

This study also identifies key microbial and enzymatic players in the global hydrogen cycle. The group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase is the second hydrogenase lineage shown to have a role in atmospheric H2 oxidation across multiple bacterial phyla. The group 1h enzyme is probably the main sink of the H2 cycle given it is the predominant hydrogenase in most soils [4, 11, 61]. However, the group 2a enzyme is moderately to highly abundant in many soil, marine, and geothermal environments [62], among others, and hence is also likely to be a key regulator of H2 fluxes. This study also reports atmospheric H2 oxidation for the first time in two globally dominant phyla, Proteobacteria and Gemmatimonadota, and uncovers A. ferrooxidans as the first H2-scavenging autotroph. Until recently, atmospheric H2 oxidation was thought to be primarily mediated by heterotrophic Actinobacteriota [1, 10,11,12], but it is increasingly apparent that multiple aerobic lineages are responsible [4, 16, 17, 19, 33]. Some six phyla have now been described that are capable of atmospheric H2 oxidation and, given the group 2a [NiFe]-hydrogenase is encoded by at least eight other phyla, others will likely soon be described. It is possible that atmospheric H2 oxidation extends to other important groups, such as nitrite-oxidising Nitrospirota [30], methane-oxidising Proteobacteria [53], and potentially even oxygenic phototrophs; while Cyanobacteria are known to recycle endogenously-produced H2 [26, 63, 64], it should be tested whether they can also scavenge exogenous H2. Indeed, while atmospheric H2 oxidisers were only recently discovered [10, 14, 65], it is now plausible that these bacteria may represent the rule rather than the exception among aerobic H2 oxidisers.

References

Greening C, Constant P, Hards K, Morales SE, Oakeshott JG, Russell RJ, et al. Atmospheric hydrogen scavenging: from enzymes to ecosystems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:1190–9.

Ehhalt DH, Rohrer F. The tropospheric cycle of H2: a critical review. Tellus B. 2009;61:500–35.

Constant P, Poissant L, Villemur R. Tropospheric H2 budget and the response of its soil uptake under the changing environment. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407:1809–23.

Greening C, Biswas A, Carere CR, Jackson CJ, Taylor MC, Stott MB, et al. Genomic and metagenomic surveys of hydrogenase distribution indicate H2 is a widely utilised energy source for microbial growth and survival. ISME J. 2016;10:761–77.

Kanno M, Constant P, Tamaki H, Kamagata Y. Detection and isolation of plant-associated bacteria scavenging atmospheric molecular hydrogen. Environ Microbiol. 2015;18:2495–506.

Kessler AJ, Chen Y-J, Waite DW, Hutchinson T, Koh S, Popa ME, et al. Bacterial fermentation and respiration processes are uncoupled in permeable sediments. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:1014–23.

Khdhiri M, Hesse L, Popa ME, Quiza L, Lalonde I, Meredith LK, et al. Soil carbon content and relative abundance of high affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria predict atmospheric H2 soil uptake activity better than soil microbial community composition. Soil Biol Biochem. 2015;85:1–9.

Lynch RC, Darcy JL, Kane NC, Nemergut DR, Schmidt SK. Metagenomic evidence for metabolism of trace atmospheric gases by high-elevation desert actinobacteria. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:698.

Ji M, Greening C, Vanwonterghem I, Carere CR, Bay SK, Steen JA, et al. Atmospheric trace gases support primary production in Antarctic desert surface soil. Nature. 2017;552:400–3.

Constant P, Chowdhury SP, Pratscher J, Conrad R. Streptomycetes contributing to atmospheric molecular hydrogen soil uptake are widespread and encode a putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:821–9.

Constant P, Chowdhury SP, Hesse L, Pratscher J, Conrad R. Genome data mining and soil survey for the novel Group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase to explore the diversity and ecological importance of presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:6027–35.

Greening C, Berney M, Hards K, Cook GM, Conrad R. A soil actinobacterium scavenges atmospheric H2 using two membrane-associated, oxygen-dependent [NiFe] hydrogenases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:4257–61.

Schäfer C, Friedrich B, Lenz O. Novel, oxygen-insensitive group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase in Ralstonia eutropha. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:5137–45.

Constant P, Poissant L, Villemur R. Isolation of Streptomyces sp. PCB7, the first microorganism demonstrating high-affinity uptake of tropospheric H2. ISME J. 2008;2:1066–76.

Meredith LK, Rao D, Bosak T, Klepac-Ceraj V, Tada KR, Hansel CM, et al. Consumption of atmospheric hydrogen during the life cycle of soil-dwelling actinobacteria. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2014;6:226–38.

Greening C, Carere CR, Rushton-Green R, Harold LK, Hards K, Taylor MC, et al. Persistence of the dominant soil phylum Acidobacteria by trace gas scavenging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10497–502.

Myers MR, King GM. Isolation and characterization of Acidobacterium ailaaui sp. nov., a novel member of Acidobacteria subdivision 1, from a geothermally heated Hawaiian microbial mat. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:5328–35.

Islam ZF, Cordero PRF, Feng J, Chen Y-J, Bay S, Gleadow RM, et al. Two Chloroflexi classes independently evolved the ability to persist on atmospheric hydrogen and carbon monoxide. ISME J. 2019;13:1801–13.

Schmitz RA, Pol A, Mohammadi SS, Hogendoorn C, van Gelder AH, Jetten MSM, et al. The thermoacidophilic methanotroph Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV oxidizes subatmospheric H2 with a high-affinity, membrane-associated [NiFe] hydrogenase. ISME J 2020;14:1223–32.

Berney M, Cook GM. Unique flexibility in energy metabolism allows mycobacteria to combat starvation and hypoxia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8614.

Berney M, Greening C, Conrad R, Jacobs WR, Cook GM. An obligately aerobic soil bacterium activates fermentative hydrogen production to survive reductive stress during hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:11479–84.

Cordero PRF, Grinter R, Hards K, Cryle MJ, Warr CG, Cook GM, et al. Two uptake hydrogenases differentially interact with the aerobic respiratory chain during mycobacterial growth and persistence. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:18980–91.

Greening C, Villas-Bôas SG, Robson JR, Berney M, Cook GM. The growth and survival of Mycobacterium smegmatis is enhanced by co-metabolism of atmospheric H2. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103034.

Liot Q, Constant P. Breathing air to save energy – new insights into the ecophysiological role of high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase in Streptomyces avermitilis. Microbiologyopen. 2016;5:47–59.

Søndergaard D, Pedersen CNS, Greening C. HydDB: a web tool for hydrogenase classification and analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34212.

Papen H, Kentemich T, Schmülling T, Bothe H. Hydrogenase activities in cyanobacteria. Biochimie. 1986;68:121–32.

Houchins JP, Burris RH. Occurrence and localization of two distinct hydrogenases in the heterocystous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. Strain 7120. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:209–14.

Tamagnini P, Axelsson R, Lindberg P, Oxelfelt F, Wünschiers R, Lindblad P. Hydrogenases and hydrogen metabolism of cyanobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:1–20.

Bothe H, Schmitz O, Yates MG, Newton WE. Nitrogen fixation and hydrogen metabolism in cyanobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74:529–51.

Koch H, Galushko A, Albertsen M, Schintlmeister A, Gruber-Dorninger C, Lucker S, et al. Growth of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria by aerobic hydrogen oxidation. Science. 2014;345:1052–4.

Drobner E, Huber H, Stetter KO. Thiobacillus ferrooxidans, a facultative hydrogen oxidizer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2922–3.

Berney M, Greening C, Hards K, Collins D, Cook GM. Three different [NiFe] hydrogenases confer metabolic flexibility in the obligate aerobe Mycobacterium smegmatis. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:318–30.

Islam ZF, Cordero PRF, Greening C. Putative iron-sulfur proteins are required for hydrogen consumption and enhance survival of mycobacteria. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2749.

Taylor SW, Fahy E, Zhang B, Glenn GM, Warnock DE, Wiley S, et al. Characterization of the human heart mitochondrial proteome. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:281–6.

Park D, Kim H, Yoon S. Nitrous oxide reduction by an obligate aerobic bacterium, Gemmatimonas aurantiaca strain T-27. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83:e00502–17.

Razzell WE, Trussell PC. Isolation and properties of an iron-oxidizing Thiobacillus. J Bacteriol. 1963;85:595–603.

Valdés J, Pedroso I, Quatrini R, Dodson RJ, Tettelin H, Blake R, et al. Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans metabolism: from genome sequence to industrial applications. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:597.

Hanada S, Hiraishi A, Shimada K, Matsuura K. Chloroflexus aggregans sp. nov., a filamentous phototrophic bacterium which forms dense cell aggregates by active gliding movement. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1995;45:676–81.

Otaki H, Everroad RC, Matsuura K, Haruta S. Production and consumption of hydrogen in hot spring microbial mats dominated by a filamentous anoxygenic photosynthetic bacterium. Microbes Environ. 2009;27:293–9.

Kawai S, Nishihara A, Matsuura K, Haruta S. Hydrogen-dependent autotrophic growth in phototrophic and chemolithotrophic cultures of thermophilic bacteria, Chloroflexus aggregans and Chloroflexus aurantiacus, isolated from Nakabusa hot springs. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2019;366:fnz122.

Heinhorst S, Baker SH, Johnson DR, Davies PS, Cannon GC, Shively JM. Two copies of form I RuBisCO genes in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270. Curr Microbiol. 2002;45:115–17.

Klatt CG, Bryant DA, Ward DM. Comparative genomics provides evidence for the 3-hydroxypropionate autotrophic pathway in filamentous anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria and in hot spring microbial mats. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2067–78.

Zhang H, Sekiguchi Y, Hanada S, Hugenholtz P, Kim H, Kamagata Y, et al. Gemmatimonas aurantiaca gen. nov., sp. nov., a Gram-negative, aerobic, polyphosphate-accumulating micro-organism, the first cultured representative of the new bacterial phylum Gemmatimonadetes phyl. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:1155–63.

Zammit CM, Mutch LA, Watling HR, Watkin ELJ. The recovery of nucleic acid from biomining and acid mine drainage microorganisms. Hydrometallurgy. 2011;108:87–92.

Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, et al. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e115.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–9.

Parks DH, Chuvochina M, Waite DW, Rinke C, Skarshewski A, Chaumeil P-A, et al. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:996–1004.

Chaumeil P-A, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P, Parks DH. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics. 2020;6:1925–7.

Kawasumi T, Igarashi Y, Kodama T, Minoda Y. Hydrogenobacter thermophilus gen. nov., sp. nov., an extremely thermophilic, aerobic, hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1984;34:5–10.

Klenk H-P, Lapidus A, Chertkov O, Copeland A, Del Rio TG, Nolan M, et al. Complete genome sequence of the thermophilic, hydrogen-oxidizing Bacillus tusciae type strain (T2 T) and reclassification in the new genus, Kyrpidia gen. nov. as Kyrpidia tusciae comb. nov. and emendation of the family Alicyclobacilla. Stand Genom Sci. 2011;5:121.

Hogendoorn C, Pol A, Picone N, Cremers G, van Alen TA, Gagliano AL, et al. Hydrogen and carbon monoxide-utilizing Kyrpidia spormannii species from Pantelleria Island, Italy. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:951.

Hedrich S, Johnson DB. Aerobic and anaerobic oxidation of hydrogen by acidophilic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2013;349:40–45.

Grostern A, Alvarez-Cohen L. RubisCO-based CO2 fixation and C1 metabolism in the actinobacterium Pseudonocardia dioxanivorans CB1190. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:3040–53.

Auernik KS, Kelly RM. Physiological versatility of the extremely thermoacidophilic archaeon Metallosphaera sedula supported by transcriptomic analysis of heterotrophic, autotrophic, and mixotrophic growth. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:931–5.

Mohammadi S, Pol A, van Alen TA, Jetten MSM, Op den Camp HJM. Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV, a thermoacidophilic ‘Knallgas’ methanotroph with both an oxygen-sensitive and -insensitive hydrogenase. ISME J. 2017;11:945–58.

Tveit AT, Hestnes AG, Robinson SL, Schintlmeister A, Dedysh SN, Jehmlich N, et al. Widespread soil bacterium that oxidizes atmospheric methane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:8515–24.

Conrad R. Soil microorganisms oxidizing atmospheric trace gases (CH4, CO, H2, NO). Indian J Microbiol. 1999;39:193–203.

Spear JR, Walker JJ, McCollom TM, Pace NR. Hydrogen and bioenergetics in the Yellowstone geothermal ecosystem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2555–60.

Ferrera I, Sanchez O. Insights into microbial diversity in wastewater treatment systems: How far have we come? Biotechnol Adv. 2016;34:790–802.

Mielke RE, Pace DL, Porter T, Southam G. A critical stage in the formation of acid mine drainage: Colonization of pyrite by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans under pH‐neutral conditions. Geobiology. 2003;1:81–90.

Constant P, Chowdhury SP, Hesse L, Conrad R. Co-localization of atmospheric H2 oxidation activity and high affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria in non-axenic soil and sterile soil amended with Streptomyces sp. PCB7. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43:1888–93.

Cordero PRF, Bayly K, Leung PM, Huang C, Islam ZF, Schittenhelm RB, et al. Atmospheric carbon monoxide oxidation is a widespread mechanism supporting microbial survival. ISME J. 2019;13:2868–81.

Eichner MJ, Basu S, Gledhill M, de Beer D, Shaked Y. Hydrogen dynamics in Trichodesmium colonies and their potential role in mineral iron acquisition. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1565.

Houchins JP, Burris RH. Comparative characterization of two distinct hydrogenases from Anabaena sp. strain 7120. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:215–21.

Greening C, Grinter R, Chiri E. Uncovering the metabolic strategies of the dormant microbial majority: towards integrative approaches. mSystems. 2019;4:e00107–19.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an ARC DECRA Fellowship (DE170100310; awarded to C.G.), an ARC Discovery Grant (DP200103074; awarded to CG and RG), an NHMRC EL2 Fellowship (APP1178715; salary for CG), and Australian Government Research Training Program Stipend Scholarships (awarded to ZFI and KB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CG and ZFI conceived this study. CG, ZFI, and RG supervised this study. CG, ZFI, and CW designed experiments. ZFI, CW, and KB performed experiments. ZFI, CW, and CG analysed data. EJG and GS contributed to study conception and experimental development. ZFI, CG, and CW wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Islam, Z.F., Welsh, C., Bayly, K. et al. A widely distributed hydrogenase oxidises atmospheric H2 during bacterial growth. ISME J 14, 2649–2658 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-0713-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-0713-4

This article is cited by

-

Trace gas oxidation sustains energy needs of a thermophilic archaeon at suboptimal temperatures

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Structural basis for bacterial energy extraction from atmospheric hydrogen

Nature (2023)

-

Molecular hydrogen in seawater supports growth of diverse marine bacteria

Nature Microbiology (2023)

-

Microbial oxidation of atmospheric trace gases

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2022)

-

A nitrite-oxidising bacterium constitutively consumes atmospheric hydrogen

The ISME Journal (2022)