Abstract

How microbe–microbe interactions dictate microbial complexity in the mosquito gut is unclear. Previously we found that, Serratia, a gut symbiont that alters vector competence and is being considered for vector control, poorly colonized Aedes aegypti yet was abundant in Culex quinquefasciatus reared under identical conditions. To investigate the incompatibility between Serratia and Ae. aegypti, we characterized two distinct strains of Serratia marcescens from Cx. quinquefasciatus and examined their ability to infect Ae. aegypti. Both Serratia strains poorly infected Ae. aegypti, but when microbiome homeostasis was disrupted, the prevalence and titers of Serratia were similar to the infection in its native host. Examination of multiple genetically diverse Ae. aegypti lines found microbial interference to S. marcescens was commonplace, however, one line of Ae. aegypti was susceptible to infection. Microbiome analysis of resistant and susceptible lines indicated an inverse correlation between Enterobacteriaceae bacteria and Serratia, and experimental co-infections in a gnotobiotic system recapitulated the interference phenotype. Furthermore, we observed an effect on host behavior; Serratia exposure to Ae. aegypti disrupted their feeding behavior, and this phenotype was also reliant on interactions with their native microbiota. Our work highlights the complexity of host–microbe interactions and provides evidence that microbial interactions influence mosquito behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mosquitoes harbor a variety of diverse microbes that profoundly alter host phenotypes [1,2,3]. In general, the bacterial microbiome can vary considerably between mosquito species and individuals, but within an individual, it comprised relatively few bacterial taxa [4, 5]. It is becoming more apparent that a variety of factors contribute to this variation, but we have a lack of understanding regarding why some taxa are present in a host, yet others are absent. In mosquitoes and other insects, much effort has been undertaken to characterize the infection status of species and populations for specific endosymbiotic bacteria such as Wolbachia [6,7,8,9], yet few studies have examined the infection prevalence of specific gut-associated bacteria in mosquito vectors. It is evident that several gut-associated bacterial taxa are common between phylogenetically diverse mosquito species [4, 5], but less attention has been paid to identifying incompatible hos–microbe associations and the mechanism(s) behind this incompatibility.

Microbiome assembly in mosquitoes is influenced by the environment, host and bacterial genetics, and stochastic processes. While the host is instrumental in maintaining microbiome homeostasis [10,11,12,13,14], evidence is emerging that bacterial genetics and microbe–microbe interactions also dictate the prevalence and abundance of microbiota [15,16,17,18]. These processes are important as the microbiome can influence the ability of mosquitoes to transmit pathogens [3, 19, 20], but potentially other traits related to vectorial capacity. Evidence from other insect systems shows a role for commensal microbes influencing behavior [21, 22]. In mosquiotes, pathogen infection can also reduce feeding rates and host seeking behavior, possibly by altering expression of odorant binding proteins or immunity-related genes [23,24,25,26]; however, less know how gut-associated microbes alter these phenotypes. Therefore, a greater appreciation of factors that influence colonization of the mosquito gut and how microbes effect the host is critical for deploying microbial-based approaches to control mosquito-borne disease [23, 24].

Serratia is a ubiquitous genus of gut symbionts that is known to infect a diverse array of insects, including taxa within the Homopteran, Hymenopteran, Dipteran, and Lepidopteran orders [25,26,27,28,29,30]. Several medically relevant vectors also harbor this bacterium [31,32,33,34,35]. In mosquitoes, Serratia appears to broadly infect Culicine and Anopheles mosquitoes [36,37,38,39], and these infections can have important phenotypic effects including altering the ability of these vectors to transmit pathogens [40,41,42]. Previosuly, we found a species-specific infection cline in Serratia levels in Culex quinquefasciatus, Ae. albopictus, and Ae. aegypti mosquitoes reared under identical conditions within the same insectary [4]. Serratia was a dominant member of the microbiota within Cx. quinquefasciatus, infected Ae. albopictus at low levels, and poorly infected or was absent from Ae. aegypti [4]. We also found that field-collected Ae. aegypti from the Houston region (USA) lacked Serratia [4].

Other studies have found variable results in respect to the prevalence of Serratia in the yellow fever mosquito. Using high-throughput 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, Serratia was found to be absent or at low levels in some Ae. aegypti field populations [5, 40,41,42,43], yet present in others [37, 44]. Culture-dependent approaches have also confirmed the presence of Serratia in this mosquito species [45,46,47,48]. The variable nature of infection in the field could be due to the presence or absence of this bacterium in the local aquatic environment; however, this does not explain the infection cline we observed in our insectary when rearing Ae. aegypti given that Cx. quinquefasciatus, which reared in the same insectary, was heavily infected [4]. The lack of Serratia infection in these lab-reared Ae. aegypti mosquitoes suggests that there is a maladaptation between this particular mosquito line and Serratia strains.

To investigate the incompatibility between Serratia and the yellow fever mosquito, we isolated and characterized two distinct strains of S. marcescens present within the Cx. quinquefasciatus microbiome, and examined their ability to infect Ae. aegypti. We found that both S. marcescens strains poorly infected several Ae. aegypti lines. However, inducing dysbiosis in the native microbiota with antibiotics facilitated infections, suggesting the incompatibility was related to microbe–microbe interactions. In addition to microbial antagonism, we found that infection with these S. marcescens strains disrupted the feeding behavior of mosquitoes. We further show the phenotypes induced by S. marcescens are driven by interactions with Enterobacteriaceae bacteria. Our work highlights the complexity of host–microbe interactions and provides further evidence that microbial exclusion influences microbiome composition and abundance within mosquitoes. These results are also relevant in the context of the holobiont, whereby both the host and the associated microbiota dictate organism phenotypes.

Methods

Mosquito rearing

Colony mosquitoes were reared at 27 °C with 80% humidity in the UTMB insectary. Mosquitoes were fed 10% sucrose ad libitum and maintained at a 12:12 light:dark cycle. Mosquitoes were fed with defibrinated sheep blood (Colorado Serum Company, Denver, CO) using a hemotek membrane feeder. Table S1 lists the colony mosquitoes used in experiments.

Isolation and characterization of S. marcescens from Culex quinquefasciatus

Homogenates of Cx. quinquefasciatus were stored in PBS at −80 °C as a glycerol stock. S. marcescens was isolated using conventional microbiological culturing. Briefly, LB plates were inoculated and incubated at 30 °C. Individual bacterial colonies were selected and purified from two different Culex mosquitoes. Two S. marcescens strains, named CxSm1 and CxSm2, were selected. Both strains had a red pigmentation, although intensity of the color varied between strains. In addition, there were differences in swimming motility and oxidase activity. These strains were subcultured for species identification by PCR amplifying the variable region of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene using universal bacterial primers. Primer sequences are listed in Table S2. Swimming motility was determined by inoculating LB medium (0.35% agar), incubating at 30 °C overnight, and then quantifying motility toward the periphery of the plate [49]. DB BBLTM oxidase reagent droppers (BD & Comp., Sparks, MD) were used to detect cytochrome oxidase activity in bacteria following the manufacturer’s instructions. Scanning electron microscopy was conducted as previously described [50, 51].

Selection of S. marcescens antibiotic-resistant mutants

S. marcescens antibiotic-resistant mutants were created as described [52] with some modification. Briefly, tubes containing 5 ml of LB broth with different concentrations of streptomycin (Sm) (Sigma) and rifampicin (Rif) (Sigma) (range: 0 [control] and 5, 10, 25, 50 μg/ml) were inoculated with 0.1 ml of a dilution of the bacterial cultures to obtain an inoculum of ~106 colony forming unit (CFU)/ml. After overnight incubation at 30 °C, bacterial aliquots from the tubes with the highest concentration of appropriated antibiotic were inoculated in LB broth [Sm supplemented (range: 0 [control], 25, 50, 100 μg/ml) and Rif supplemented (range: 0 [control], 50, 100, 200, 250, 500 μg/ml)] and incubated overnight at 30 °C. Finally, after several passages in the presence of corresponding antibiotics, the CxSm1RifR (MIC 400 μg/ml) and CxSm2SmR (MIC 150 μg/ml) mutants were selected. The same approach was used to create a CedeceaRifR mutant.

Oral infection of mosquitoes with S. marcescens

The S. marcescens CxSm1RifR and CxSm2SmR strains were used for mosquito oral infection. Bacteria were grown in a 25-ml LB medium overnight culture at 30 °C containing either Rif (200 μg/ml) or Sm (100 μg/ml). Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 20 min and then washed twice with sterile PBS and suspended in 2.5-ml PBS. Bacterial PBS stock was titrated by serial dilutions and quantified by plating on LB agar and measuring CFUs. The bacterial PBS stock dilutions were resuspended in 10% sterile sucrose to a final concentration of 1 × 107 cells/ml. When supplementing antibiotics in the sugar meal, Rif (200 μg/ml) or Sm (100 μg/ml) was added to the sucrose solution. Mosquitoes were fed with a bacterial infected solution for 3 days. Then, mosquitoes were fed with 10% sterile sucrose or 10% sterile sucrose plus corresponded antibiotic, as required. At each time point, ten mosquitoes from each group were aspirated, surface sterilized, and homogenized in 250-μl PBS separately. Serial dilutions of mosquito homogenate were plated on LB agar and LB agar with the appropriate antibiotic and CFUs quantified. Experiments were repeated twice or three times as described in the figure legends.

Microbiome analysis of Ae. aegypti lines

The microbiomes of Ae. aegypti lines were analyzed using barcoded high-throughput amplicon sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene using a similar approach as previously described [4, 53]. DNA was extracted (QIAamp DNA Mini kit, QIAgen, Valencia, CA) from individual whole surface sterilized mosquitoes 5 days post eclosion (N = 15). To evaluative possible contamination, a spike in positive control [54] was amplified under the same conditions as genomic DNA isolated from mosquitoes. The spike in control was synthesized as a gBlock (Intergrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) and 100 pmole of template was used as template for PCRs. High-throughput sequencing of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene was performed using gDNA isolated from each sample. Sequencing libraries for each isolate were generated using universal 16S rRNA V3-V4 region primers in accordance with Illumina 16S rRNA metagenomic sequencing library protocols [55]. The samples were barcoded for multiplexing using Nextera XT Index Kit v2 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq instrument using a MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 (500-cycles). To identify the presence of known bacteria, sequences were analyzed using the CLC Genomics Workbench 11.0.1 Microbial Genomics Module. Reads were trimmed of sequencing adapters and barcodes, and any sequences containing nucleotides below the quality threshold of 0.05 (using the modified Richard Mott algorithm) and those with two or more unknown nucleotides or sequencing adapters were removed. Reference-based OTU picking was performed using the SILVA SSU v128 97% database [56]. Sequences present in more than one copy but not clustered to the database were placed into de novo OTUs (99% similarity) and aligned against the reference database with 80% similarity threshold to assign the “closest” taxonomical name where possible. Chimeras were removed from the dataset if the absolute crossover cost was three using a k-mer size of six. Alpha diversity was measured using Shannon entropy (OTU level), rarefaction sampling without replacement, and with 100,000 replicates at each point. Beta diversity was calculated and nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plots were created using Bray–Curtis dissimilarity. Differentially abundant bacteria (family level) were identified using analysis of composition of microbiomes (ANCOM) with a significance level of p < 0.05 [57].

The total Serratia load within each mosquito line was assessed by qPCR. The S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase (PFS) gene of Serratia was amplified with the primers psf1-F and psf-R [58]. The Ae. aegypti or Cx. quinquesfactius S7 gene was amplified with aeg-S7-F and aeg-S7-R or Cq-S7-F and Cq-S7-R primers, respectively [4]. The PCR was done in a 10-μl reaction containing 1 μM of each primer, 1× SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and 2 μl of genomic DNA template. Cycling conditions involved an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 1 min at 60 °C. Fluorescence readings were taken at 60 °C after each cycle before deriving a melting curve (60–95 °C) to confirm the identity of the PCR product. The PCR was carried out on the ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System. Relative abundance was calculated by comparing the Serratia load to the single-copy mosquito gene.

Life history assays

To determine blood-feeding success, mosquitoes were offered a sheep blood meal using a hemotek feeding system. Cups of 25 female mosquitoes were starved for 24 h prior to blood feeding. Mosquitoes were given the opportunity to feed, and then the number of blood-fed mosquitoes were counted. For a subset of mosquitoes, the prevalence of S. marcescens in blood-fed and non-blood-fed mosquitoes was determined by plating on selective media. To examine the reproductive output, we measured the number of eggs produced by a blood feed female. Individual blood-fed females were placed into a vial with an oviposition site. After 4 days, the number of eggs were counted. Females that did not lay were excluded from the analysis. For most assays, the mortality of mosquitoes was quantified daily by counting and removing dead mosquitoes in cups.

Genome sequencing

DNA isolation from bacteria was done using the PureLink™ Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Thermo Scientific, Carlsbad, CA). The Oxford Nanopore Technologies’s (ONT) MinION libraries were created with the 1D Native barcoding genomic DNA kit (with EXP-NBD103 and SQK-LSK108), following standard protocol (ver. NBE_9006_v103_revO_21Dec2016). In brief, 1.5 µg of each genomic DNA was fragmented (Covaris g-TUBE), end-repaired (NEBNext® Ultra™ II End Repair/dA-Tailing Module, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), barcodes are ligated, pooled in equal-molar amounts and finally adapter ligated. The pooled library was loaded to a FLO-MIN106 flow cell and sequenced using the default settings of the MinKNOW for at least 24 h. Base calling was conducted with Albacore (release 2.3.3, https://nanoporetech.com/) with the following parameters: -k SQK-LSK108 -f FLO-MIN106 --barcoding. Data trimming and quality filtering was conducted with Porechop (https://github.com/rrwick/Porechop) with the following parameter: --discard_unassigned.

In addition, bacterial strains were submitted for short-read Illumina sequencing to 30X coverage using the Standard Whole-Genome Service from the MicrobesNG service (www.microbesng.uk, Birmingham, UK). Assemblies were performed using unicycler [59], generating a hybrid assembly using both long- and short-read sequences as input for each strain, respectively, for the assembly process. FastANI (average nucleotide identity) was used on a set of Serratia reference genomes retrieved from NCBI (Table S3) to confirm the species allocation. ANI analysis shows that CxSm1 and CxSm2 are highly similar to Serratia sp. Y25, which likely forms a subspecies of S. marcescens with an average ANI distance of 0.054 (Table S4 and Fig. S1); there was no difference in ANI level between CxSm1 and CxSm2. Mapping against S. marcescens reference strains thus resulted in high numbers of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; 252,113 and 253,191 for CxSm1 and CxSm2, respectively, against NZ_HG326223 DB11); whereas 44,435 and 44,913 SNPs were detected when mapping against the Serratia sp. YD25 genome (CP016948.1). 44,169 of these were ACGT-only sites where at least one of the sequences differs from the reference; 29 of these core genome SNPs differ between CxSm1 and CxSm2. Mapping was performed using SMALT v0.7.4 (ref: SMALT: a mapper for DNA sequencing reads. Available from: https://sourceforge.net/projects/smalt/) to produce a BAM file. Variation detection was performed using SAMtools mpileup v0.1.19 [60] with parameters “-d 1000 -DSugBf” and bcftools v0.1.19 (ref: bcftools: utilities for variant calling and manipulating VCFs and BCFs. Available from: http://samtools.github.io/bcftools/) to produce a BCF file of all variant sites. The option to call genotypes at variant sites was passed to the bcftools call. All bases were filtered to remove those with uncertainty in the base call. The bcftools variant quality score was required to be >50 (quality < 50) and mapping quality greater than 30 (map_quality < 30). If the same base call was not produced by all reads, the allele frequency, as calculated by bcftools, was required to be either 0 for bases called the same as the reference, or 1 for bases called as a SNP (af1 < 0.95). The majority base call was required to be present in at least 75% of reads mapping at the base (ratio < 0.75), and the minimum mapping depth required was four reads, at least two of which had to map to each strand (depth < 4, depth_strand < 2). Finally, strand_bias was required to be <0.001, map_bias <0.001, and tail_bias <0.001. If any of these filters were not met, the base was called as uncertain. All sequence data are available under BioProject number PRJNA641526.

Results

Serratia strain characterization

Two strains of Serratia were isolated from Cx. quinquefasciatus by conventional microbiology procedures. 16S rRNA sequencing indicated that these strains were S. marcescens, and each produced a red pigmentation when grown in a culture, which is indicative of this species (Fig. S2a). Although the 16S rRNA sequence was identical between strains, we saw phenotypic differences in their swimming motility, oxidase activity, and capacity to form biofilms, suggesting that they were phenotypically divergent (Fig. S2a, b). Swimming motility has been implicated in host gut colonization of several hosts [61, 62], and these traits can influence pathogen infection in mosquitoes [63]. To further characterize these strains (named CxSm1 and CxSm2), we sequenced their genomes using nanopore and Illumina technologies. Comparative genome analysis indicated high similarity between the two strains (no difference reported at ANI level; 29 core SNPs differed between CxSm1 and CxSm2 when compared to Serratia sp. Y25; for details see “Methods”). They showed 94.7% ANI similarity to S. marcescens when comparing with a set of Serratia reference genomes, indicating that these might represent a subspecies of S. marcescens (Fig. S1 and Tables S3, S4). Recent work has indicated a population structure in S. marcescens with at least two different clades [64], which might be an indication for several subspecies or indeed a species complex, as is for example seen for Klebsiella pneumoniae or Enterobacter cloacae [65, 66]. To aid our recovery of each of these S. marcescens strains on media, we selected for rifampicin and streptomycin spontaneous antibiotic-resistant isolates for CxSm1 and CxSm2, respectively (antibiotic-resistant strains named CxSm1RifR and CxSm2SmR).

Serratia colonization of mosquitoes

We investigated the ability of Serratia to colonize the novel Ae. aegypti host by reinfecting bacteria into mosquitoes in a 10% sucrose meal and monitored infection dynamics in the mosquito over time. The Serratia infection was completely lost from Ae. aegypti by 12 dpi, whereas the bacterial prevalence in the native host, Cx. quinquefasciatus, remained constantly high with infection levels ranging from 100% infection for CxSm1RifR to 80% infection for CxSm2SmR at 12 dpi (Fig. 1a). Of the mosquitoes that were infected, both S. marcescens strains infected Ae. aegypti (Galveston) at significantly lower densities compared to their native host, Cx. quinquefasciatus (Fig. 1a). For example, at 3 dpi, we saw ~1000 times less Serratia in Ae. aegypti compared to Cx. quinquefasciatus (Fig. 1a). We also examined other culturable microbiota by plating mosquito homogenates on nonselective LB plates, and in general, we saw few changes in the number of CFUs between groups in either Ae. aegypti or Cx. quinquefasciatus (Fig. S3), suggesting Serratia infection had minimal effect on the total bacterial load of culturable microbiota in mosquitoes. The inability of Serratia to persistently infect Ae. aegypti, which was not observed for other bacteria (Fig. S3), suggests that barriers, either of bacterial or host origin, were promoting the maladaption between these Serratia strains and this line of Ae. aegypti.

Infection of CxSm1RifR and CxSm2SmR into Cx. quinquefasciatus (gray) and Ae. aegypti (black) mosquitoes (a). Solid lines indicate rearing on sucrose while dotted lines and pill cartoon indicated rearing on antibiotic. The line below shows the time line of the experiments and CFU sampling is indicated by the plates. Infection of CxSm1RifR and CxSm2SmR strains into antibiotic-treated or -untreated Ae. aegypti (b). Rifampamicin or spectinomycin was administered to mosquitoes in a sugar meal (capsule indicates antibiotic treatment). For both a and b, the upper panel shows a schematic of experimental design. The line graph indicates the titer of Serratia in mosquitoes, and the pie graph indicates infection prevalence in mosquitoes. For each time point, ten mosquitoes were sampled. Letters indicate significance from the Mann–Whitney test comparing density within a time point. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in Serratia in Cx. quinquefasciatus to Ae. aegypti (a) or antibiotic- and nonantibiotic-treated mosquitoes (b) using a Mann–Whitney test for densinty Fisher’s exact test for prevalence. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Both experiments (a, b) were repeated three times and comparible results were seen between replicates.

Microbial interaction in the mosquito gut

To gain insights into the mechanism promoting the incompatibility between Serratia and Ae. aegypti, we repeated infections in antibiotic-treated mosquitoes as we speculated that the native microbiota of mosquitoes might interfere with the colonization of the host (Fig. 1b). We formulated this hypothesis as we have previously seen evidence of bacterial exclusion of symbiotic microbes in mosquitoes [4, 18]. Strikingly, both CxSm1RifR and CxSm2SmR colonized mosquitoes at significantly higher titers when mosquitoes were treated with antibiotics compared to mosquitoes reared conventionally without antibiotics (Mann–Whitney test; CxSm1RifR; day 3 p < 0.002, day 9 p < 0.01; day 12 p < 0.0001, CxSm2SmR; day 3 p < 0.03, day 9 p < 0.01; day 12 p < 0.01) (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, for both Serratia strains, significantly more mosquitoes were infected at day 12 in antibiotic-treated mosquitoes compared to untreated (Fisher’s exact test; CxSm1RifR p = 0.01, CxSm2SmR p = 0.0007). The levels of Serratia in Ae. aegypti after microbiome homeostasis that were disrupted by antibiotics were comparable to infections in the native host Cx. quinquesfasciatus (Fig. 1a). These data indicated that the Ae. aegypti (Galveston) line had the capacity to harbor Serratia, and that the incompatibility in mosquitoes with an intact microbiome (Fig. 1a, [4]) was due to members of the native microbiota inhibiting Serratia, as opposed to intrinsic host factors or genetic factors of the S. marcescens strains.

To determine how widespread these microbial interactions were in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, we investigated eight diverse lines for native Serratia infections and their capacity to be infected with CxSm1RifR. When examining the native Serratia load by qPCR, seven of the eight Ae. aegypti lines had significantly lower titers compared to C. quinquefasciatus (Fig. 2a). Intriguingly, an Ae. aegypti line from Thailand had a high Serratia load that was comparable to the infection in the native Culex host. We also quantified Serratia levels in two other Cx. quinquefasciatus lines and found similar or higher loads of Serratia in these other lines (Fig. S4), indicating that the robust infection of Serratia in Cx. quinquefasciatus was commonplace. We then infected the CxSm1RifR Serratia strain into these eight diverse Ae. aegypti lines. For these infections we focused our attention on CxSm1RifR, as overall, it appears this strain had a greater capacity to infect Ae. aegypti compared to CxSm2SmR. We therefore hypothesized that this strain would be more likely to infect non-native hosts. Similar to our previous experiments, Serratia poorly infected the Galveston line and was eliminated by 12 dpi. In the other lines, we saw some variation in the time it took for Serratia to be eliminated, with clearance occurring rapidly in the Juchitan and Iquitos lines. Whilst the process took longer in others (Dakar, Salvador and Dominican Republic), infection was ultimately cleared from all lines. In stark contrast to these seven lines, Serratia effectively colonized the Thailand line and the Cx. quinquefasciatus at high density and prevalence. Combined, the qPCR and re-infection experiments indicated the majority of Ae. aegypti lines that were not permissive to Serratia infection, but infection dynamics in the Thailand line were similar to the native Culex host.

The density of Serratia was determined by qPCR in eight Ae. aegypti lines (a). CxSm1RifR was infected into Ae. aegypti lines and density (blue line) monitored over time (b). Total cultural microbiota (dotted line) was also quantified by culturing bacteria from homogenized mosquitoes on nonselective LB plates. Line graphs indicate titer of Serratia in mosquitoes, and pie graphs indicate infection prevalence in mosquitoes. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in Serratia prevalence in Ae. aegypti lines compared to Cx. quinquefasciatus using a Fisher’s exact test compared to the Cx. quinquefasciatus control line.

Microbiome analysis of resistant and susceptible mosquitoes

To determine which specific microbiota of Ae. aegypti altered Serratia infections, we sequenced the microbiome of four select lines that varied in the capacity to harbor the bacterium. The V3-V4 variable region of the 16S rRNA gene was sequenced from the Juchitan, Galveston, and Iquitos line, which were recalcitrant to Serratia, and the Thailand line that was able to sustain the infection similar to the native host. For each line, we sequenced 15 individuals and, on average, obtained 32,000 reads per mosquito. Rarefaction curves indicated that sufficient depth was obtained in the sequencing to adequately characterize the microbiome, while our spike in controls constituted 99.5% of the relative abundance indicating that there was negligible contamination in our sequencing (Fig. S5). Across all mosquito lines, we identify a total of 1163 bacterial OTUs, but only 55 were present in mosquitoes at an infection frequency above 1% (Table S5).

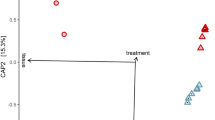

When examining taxa within the microbiome, the majority of sequences were from the Proteobacteria, while others were associated with Verrucomicrobia and Bacteroidetes. Within the Proteobacteria, the most abundant OTUs were in with the families Enterobacteriaceae, Acetobacteriaceae, and Pseudomonasaceae, while the Thailand line harbored a considerable amount of Verrucomicrobiaceae compared to the other three lines (Fig. 3a). Confirming our qPCR data, we saw minimal or no Serratia infection in the Galveston, Iquitos, or Juchitan lines, but this bacterium comprised ~4% of the relative abundance of the Thailand line (Fig. 3b). It was also noticeable that the Thailand line possessed a higher diversity of OTUs compared to the other lines (Fig. S6 and Table S5). This was corroborated by alpha diversity measures, which indicated that the Thailand line had a significantly elevated Shannon’s diversity index compared to the other three lines (Fig. 3c). To examine the community structure of the microbiome in each line, we undertook NMDS analysis based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity. Strikingly, the microbiomes of each line were significantly different from each other (Fig. 3d, p < 0.05); however, it was evident from the clustering that the Thailand line was considerably divergent compared to the other three lines.

16S rRNA amplicon sequencing was done on female adult mosquitoes 5 days post eclosion. All mosquitoes were reared in the same laboratory environment under identical conditions. The relative abundance of bacterial communities at the family (a) and genus level (b). Alpha (Shannon’s entropy; *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001) (c) and beta (NMDS) (d) diversity metrics. Differential abundance analysis (ANCOM) of bacterial families in pairwise comparisons (e) between the four lines (T—Thailand, G—Galveson, J—Juchitan, I—Iquitos). A bolded value indicates a significant difference. Positive value indicates greater adundance of bacteria in the denominator, negative indicates greater number of bacteria in the numerator in the pairwise comparison. Total bacterial load in mosquito lines measured by qPCR (f).

To examine specific taxa that may be the cause of microbial incompatibility, we undertook pairwise comparisons to identify bacteria that were differentially abundant between lines. We examined differences at the family level using ANCOM, which is specifically designed to handle variable microbiome data [57]. While the abundance of several families was significantly different between lines, the Enterobacteriaceae was the only family that was consistently reduced in the Thailand line compared to the other three lines (Fig. 3e). In addition to amplicon sequencing, we used qPCR to determine the total microbial load of mosquitoes and found that each possessed a similar density of bacteria (Fig. 3f), indicating the increase in taxa in the Thailand line were not simply due to possessing a greater number of bacteria. Taken together, these data indicated that the microbiome of the Thailand line was substantially different from the other lines and that members of the Enterobacteriaceae can inhibit Serratia infection in mosquitoes.

Co-infections in gnotobiotic infection model

To functionally demonstrate that members of the Enterobacteriaceae interfere with Serratia colonization, we undertook a series of co-infection experiments in antibiotic-treated mosquito lines. Prior to infection of the CxSm1RifR Serratia strain, we infected mosquitoes with CedeceaRifR, a member of the Enterobacteriaceae that commonly infects mosquitoes, or other Acetobacteraceae and Pseuduomonadaceae bacteria as controls (Fig. 4a). We chose Cedecea as we have previously documented that this bacterium infects Ae. aegypti effectively [4]. The infection prevalence of Serratia in the co-infected Ae. aegypti Galveston line was significantly reduced in all time points (Fig. 4b, p < 0.05, the Fisher’s exact test). In the few mosquitoes that did harbor a Serratia infection, the density was significantly lower compared to the single infection (Fig. 4b, t-test p < 0.05). These data indicated Serratia colonization was inhibited by the presence of Cedecea, and the phenotype we observed previously in conventionally reared mosquitoes could be recapitulated in a gnotobiotic setting. Similarly, we also found that the prevalence of Serratia was reduced by co-infection in the Ae. aegypti Thailand line (p = 0.05, Fisher’s exact test), although this effect was more subtle, and no significant difference was observed at 12 dpi (Fig. 4c). In contrast to co-infection with Cedecea, we found no effect in Serratia prevalence or titers when co-infected with Asaia or Pseudomonas (Fig. 4e, f), which are members of the Acetobacteraceae and Pseduomonadaceae families, respectively. Interestingly, there was evidence that Serratia interferes with Asaia infections in Ae. aegypti, as there was an initial reduction in the prevalence of Asaia in the co-infected group compared to the single infection (Fig. 4f, p = 0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Together, these co-infection studies demonstrate that inhibition of Serratia colonization in Ae. aegypti is bacteria-specific, and that antagonism occurs between members of the Enterobacteriaceae and Serratia.

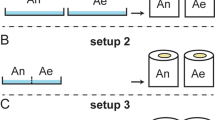

Schematic depicting the co-infection experimental design a Dotted lines and pill cartoon indicated rearing on antibiotic. The mosquito color indicates genotype (black: Galveston line, blue: Thailand line). Bacterial administration protocols and sampling time are represented above and below, respectively. Co-infection of CedeceaRifR and CxSm1RifR in Ae. aegpyti (Galveston) (b) and Thailand (c) lines. Control co-infections whereby Pseudomonas (d) or Asaia (e) were infected prior to CxSm1RifR. Line graphs show bacteria density (CFU/mosquito), and pie graphs show infection prevalence. For each time point, ten mosquitoes were sampled. Letters indicate significance from ANOVA comparing density within a time point. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between Serratia prevalence in single and co-infected mosquitoes using a Fisher’s exact test.

To determine how Cedecea influenced Serratia in its native host, we repeated co-infection experiments in Cx. quinquefasciatus using the gnotobiotic infection model. Cedecea infected Culex mosquitos less effectively compared to Aedes, with infection densities around two logs lower and an infection prevalence that dropped to 50% over the course of the experiment (Fig. 5). Despite a lower level of infection, Cedecea infection prior to Serratia reduced the infection of the latter. At 15 and 18 dpi, the prevalence of Serratia in the co-infection was 50% compared to 100% in the single infection (Fig. 5a, p = 0.03, Fisher’s exact test). We also examined the effect of Cedecea on an established Serratia infection by reversing the order each bacterium was administered to the mosquito. In this case, the prevalence of Serratia in the co-infection was significantly reduced only at the 18 dpi time point (Fig. 5b, p = 0.03 Fishers exact test). Taken together, these data show that antagonism between Serratia and other Enterobacteriaceae also occurs in Culex mosquitoes.

Infection of Cedecea followed by CxSm1RifR (a) or CxSm1RifR followed by Cedecea (b) in Cx. quinquefasciatus. Line graphs show bacteria density (CFU/mosquito), and pie graphs show infection prevalence. For each time point, ten mosquitoes were sampled. Letters indicate significance from Mann–Whitney test comparing density of CxSm1RifR single and co-infectons within a time point. For prevalence data, asterisks indicate a significant difference between Serratia prevalence in single and co-infected mosquitoes using a Fisher’s exact test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Effect of Serratia exposure on blood-feeding behavior

Anautogenous mosquitoes require a blood meal to acquire nutrition for egg development. Ingested blood alters the gut microbiota composition and abundance, often increasing total bacterial load but decreasing species richness [67, 68]. In other mosquito species, Serratia has been seen to rapidly increase in titer after a blood meal [69,70,71] and, in some cases, can be lethal to the host [38]. As such, we investigated the influence of blood feeding on Serratia-infected Ae. aegypti (Fig. 6a). We measured bacterial load in the mosquito (Fig. 6b) as well as a range of life history traits. For these experiments, we focused our attention on CxSm1RifR. In contrast to a previous study [38], we observed no fitness costs to infection in terms of mosquito survival pre- or post-blood meal (Fig. S7). After a blood meal, Serratia density precipitously increased around 100-fold. The increase in the antibiotic-treated mosquitoes was more subtle, likely because the bacterial load was initially greater, suggesting that there is an upper limit to infections. After blood feeding, Serratia infections were comparable to densities and infection frequencies seen in sugar-fed mosquitoes (Figs. 1 and 4), with levels in antibiotic-treated mosquitoes being maintained at around 1 × 106 bacteria/mosquito. In conventionally reared mosquitoes, Serratia was eliminated, albeit over a longer time period, likely due to the increased density of the bacterium after stimulation from the blood meal. Post blood feeding, Serratia densities equilibrated to levels around 106, which were comparable to infection densities seen in non-blood-fed mosquitoes (Fig. 6b). While we saw no differences in egg number (Fig. S8), in the process of conducting these experiments, we observed that CxSm1RifR-infected mosquitoes were less inclined to take a blood meal when reared on a convention sugar diet.

Schematic depicting the infection and blood-feeding experimental design (a). Infection density and prevalence of CxSm1RifR in conventional and antibiotic-fed Ae. aegypti (b). The red dotted line indicates the timing of blood meal. Significance was determined using a T-test comparing conventional and antibiotic groups for each time point. Ten mosquitoes were examined at each time point. The capsule indicates antibiotic treatment. Percentage of mosquitoes to take a blood meal for CxSm1RifR (c) or CxSm2SmR (d) infected or uninfected mosquitoes. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Either six (c) or three (d) cups were used for feeding experiments with 50 mosquitoes per cup. The CxSm1RifR experiment was replicated twice (three cups each and data pooled). Percentage Serratia administered mosquitoes infected with CxSm1RifR (e) or CxSm2SmR (f) blood-fed, or non-blood-fed groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine significance. Samples size is indicated for each group above the bars.

We therefore investigated further whether Serratia infection altered mosquito blood-feeding behavior. After providing mosquitoes with the opportunity to feed, we saw that significantly fewer females had imbibed a blood meal compared to uninfected or antibiotic-treated CxSm1RifR infected mosquitoes (Fig. 6c, ANOVA p < 0.001). Blood-feeding rates in Serratia-infected Ae. aegypti were restored when mosquitoes were fed antibiotics, indicating these behavioral changes were mediated by the interplay between CxSm1RifR and other bacterial constituents of the microbiome susceptible to antibiotics. Given this intriguing finding, we repeated these experiments with the CxSm2SmR isolate. Similar to findings with its close relative, the CxSm2SmR Serratia strain altered the blood-feeding rates in mosquitoes (Fig. 6d, ANOVA p < 0.001). Given the heterogeneity in the prevalence of CxSm1RifR and CxSm2SmR in conventionally reared mosquitoes, we examined individuals that did or did not blood feed for Serratia infection. For both CxSm1RifR (Fig. 6e) and CxSm2SmR (Fig. 6f), the Serratia infection rate was significantly higher in non-blood-fed mosquitoes compared to blood-fed (CxSm1RifR p < 0.005; CxSm2SmR p < 0.005), indicating that mosquitoes that took a blood meal were less likely to be infected with Serratia. When considering this, it is likely that the reductions we observed at the population level (Fig. 6c, d) are conservative, and the effect of Serratia infection on blood-feeding behavior is more pronounced.

Discussion

The interplay between the host and microbes can dictate insect microbiome homeostasis, but little is known regarding how microbe–microbe interactions within the gut influence microbial composition and abundance. Previously we identified a Serratia infection gradient in the arboviral vectors, Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopcitus, and Cx. quinquefasciatus, with high loads in the latter and an absence of infection in the former [4]. Here we show that Serratia poorly infects many Ae. aegypti strains and that the mechanism mediating this incompatibility is competitive exclusion with Cedecea, a member of the Enterobacteriaceae and close relatives of Serratia (also a member of the Gammaproteobacteria and the Enterobacterales, but the family Yersiniaceae). Given that Serratia can influence vector competence in mosquitoes and has been proposed as a microbe for paratransgenic control [69, 70], it is imperative we enhance our understanding of factors that influence Serratia acquisition in the mosquito gut.

After confirming that members of the microbiota were inhibiting Serratia colonization of mosquitoes, we characterized the microbiome of Ae. aegypti lines susceptible and resistant to infection. Interestingly, the susceptible Thailand line possessed a distinct and species-rich microbiome, and had significantly lower levels of Enterobacteriaceae. We speculated that this line had lost its capacity to maintain microbiome homeostasis, which subsequently enabled numerous other bacterial species to colonize. These other species likely reduced the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae in the host, as our qPCR data indicated that the Thailand line had a similar total bacterial load compared to the other lines. The reduced levels of potentially antagonistic Enterobacteriaceae in the Thailand line enabled the colonization of the Serratia at levels similar to Culex mosquitoes. This theory is strongly supported by the fact that inhibition of Serratia was restored in the Thailand line when mosquitoes were pre-infected with Cedecea.

Microbiome dysbiosis can profoundly alter several host phenotypes in insects, including symbiont processes [18]. In the Oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis, suppression of the dual oxidase gene (BdDuox) led to microbiome dysbiosis and an overabundance of Verrucomicrobiaceae bacteria [72]. Increases in Verrucomicrobiaceae have also been observed in mammalian systems when the microbiome transfers to a dysbiotic state [73,74,75,76]. In our analysis, Verrucomicrobiaceae was a dominant member of the microbiome of the Thailand line, yet was at relatively low abundance in the Iquitos and Juchitan lines and barely detectable in the Galveston line. The presence of this family suggests that the microbiome of the Thailand line was in a state of dysbiosis. In the Galveston line, the co-infection experiments recapitulated our previous results indicating that bacterial co-exclusion was the main factor driving Serratia incompatibility. However, the effects in the Thailand line were more subtle, with the presence of Cedecea only reducing the Serratia infection prevalence at earlier time points and not influencing titer. This suggests that other host factors likely contribute to the incompatibility of Serratia in the Galveston line, but these factors were deficient in the Thailand line, resulting in the more subtle phenotype.

While there are examples that a broad range of microbes can influence feeding behavior in insects, relatively little is known regarding how gut-associated microbes contribute to these phenotypes. Our data indicate that Serratia acts in concert with other microbes to reduce blood feeding. There is a complex immune interplay between gut microbes and the host [77,78,79], and it is possible that disruption of microbiome homeostatis by Serratia infection may alter basal immunity which subsequently affects feeding behavior. Alternatively, these mosquitoes may be suffering the effects of infection or microbiome dysbiosis resulting in a lack of interest in feeding. However, similar to findings in Culex mosquitoes [80], we saw little evidence for Serratia affecting other life history traits. Further studies are required to decipher the exact mechanism(s) causing this phenotype. From a vector control standpoint, reducing blood-feeding rates will greatly influence pathogen transmission. However, this phenotype is mediated by an interaction between Serratia and other native microbes of the Ae. aegpyti. Given the inherent variability in the microbiome of mosquitoes, further investigations are warranted to determine how universal this phenotype is, and in general how alterations in mosquito behaviors caused by microbiome dysbiosis can then impact upon vectorial capacity. In the laboratory setting, reduced feeding rates would act as a distinct process to eliminate Serratia infections from the microbiome of Ae. aegypti.

Another important aspect of our work is the finding that Ae. aegpyti lines reared under uniform insectary conditions have diverse microbiomes. While it was evident that the Thailand line has a particularly divergent microbiome, the microbiomes of the Juchitan, Galveston, and Iquitos lines were also distinct from each other. This is contrary to a recent finding [41], and suggests that similarity in microbiomes driven by environmental factors is not universal, and host or bacterial factors also play a role in microbiota community assembly and can lead to microbiome divergence, as shown in Drosophila [81, 82]. Here we demonstrate in mosquitoes that host genotype profoundly alters bacterial microbiome composition.

In conclusion, we show that microbe–microbe interactions influence microbiome composition and abundance in mosquito vectors. These processes are robust and can prevent the transfer of microbiota between mosquitoes that share a common environment by distinct mechanisms. Transfer of microbiota can occur in a host when microbiome homeostasis is disrupted, but this can also alter phenotypes important for host biology. Furthermore, we show that microbiota transfer can change mosquito traits that are important for pathogen transmission. From an applied standpoint, a greater understanding of the factors dictating microbial exclusion and acquisition could be exploited to develop strategies to create mosquitoes with designer microbiomes that induce desirable properties for vector control.

References

Patterson EI, Villinger J, Muthoni JN, Dobel-Ober L, Hughes GL. Exploiting insect-specific viruses as a novel strategy to control vector-borne disease. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2020;39:50–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2020.02.005.

Tawidian P, Rhodes VL, Michel K. Mosquito-fungus interactions and antifungal immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;111:103182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.103182.

Guégan M, Zouache K, Démichel C, Minard G, Tran-Van V, Potier P, et al. The mosquito holobiont:. fresh insight into mosquito-microbiota interactions. Microbiome. 2018;6:49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0435-2.

Hegde S, Khanipov K, Albayrak L, Golovko G, Pimenova M, Saldana MA, et al. Microbiome interaction networks and community structure from laboratory-reared and field-collected Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito vectors. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02160.

Osei-Poku J, Mbogo CM, Palmer WJ, Jiggins FM. Deep sequencing reveals extensive variation in the gut microbiota of wild mosquitoes from Kenya. Mol Ecol. 2012;21:5138–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05759.x.

Ricci I, Cancrini G, Gabrielli S, D’Amelio S, Favia G. Searching for Wolbachia (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) in mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae): large polymerase chain reaction survey and new identifications. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:562–7.

Rasgon JL, Scott TW. An initial survey for Wolbachia (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) infections in selected California mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2004;41:255–7.

Gloria-Soria A, Chiodo TG, Powell JR. Lack of evidence for natural wolbachia infections in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2018;7:e1002415. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjy084.

Goindin D, Cannet A, Delannay C, Ramdini C, Gustave J, Atyame C, et al. Screening of natural Wolbachia infection in Aedes aegypti, Aedes taeniorhynchus and Culex quinquefasciatus from Guadeloupe (French West Indies). Acta Trop. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.06.011.

Mitri C, Bischoff E, Belda Cuesta E, Volant S, Ghozlane A, Eiglmeier K, et al. Leucine-rich immune factor APL1 Is associated with specific modulation of enteric microbiome Taxa in the Asian malaria mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00306.

Short SM, Mongodin EF, MacLeod HJ, Talyuli OAC, Dimopoulos G. Amino acid metabolic signaling influences Aedes aegypti midgut microbiome variability. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005677. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005677.

Pang X, Xiao X, Liu Y, Zhang R, Liu J, Liu Q, et al. Mosquito C-type lectins maintain gut microbiome homeostasis. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16023. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.23.

Xiao X, Yang L, Pang X, Zhang R, Zhu Y, Wang P, et al. A Mesh-Duox pathway regulates homeostasis in the insect gut. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17020. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.20.

Zhao B, Lucas KJ, Saha TT, Ha J, Ling L, Kokoza VA, et al. MicroRNA-275 targets sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ adenosine triphosphatase (SERCA) to control key functions in the mosquito gut. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006943–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006943.

Dennison NJ, Saraiva RG, Cirimotich CM, Mlambo G, Mongodin EF, Dimopoulos G. Functional genomic analyses of Enterobacter, Anopheles and Plasmodium reciprocal interactions that impact vector competence. Malar J. 2016;15:425. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1468-2.

Hegde S, Nilyanimit P, Kozlova E, Anderson ER, Narra HP, Sahni SK, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene deletion of the ompA gene in symbiotic Cedecea neteri impairs biofilm formation and reduces gut colonization of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007883. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007883.

Ramirez JL, Short SM, Bahia AC, Saraiva RG, Dong Y, Kang S, et al. Chromobacterium Csp_P reduces malaria and dengue infection in vector mosquitoes and has entomopathogenic and in vitro anti-pathogen activities. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004398. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004398.

Hughes GL, Dodson BL, Johnson RM, Murdock CC, Tsujimoto H, Suzuki Y, et al. Native microbiome impedes vertical transmission of Wolbachia in Anopheles mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:12498–503. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1408888111.

Hegde S, Rasgon JL, Hughes GL. The microbiome modulates arbovirus transmissionin mosquitoes. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;15:97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2015.08.011.

Dennison NJ, Jupatanakul N, Dimopoulos G. The mosquito microbiota influences vector competence for human pathogens. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2014;3:6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2014.07.004.

Wong AC-N, Wang Q-P, Morimoto J, Senior AM, Lihoreau M, Neely GG, et al. Gut microbiota modifies olfactory-guided microbial preferences and foraging decisions in drosophila. Curr Biol. 2017;27:2397–.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.07.022.

Fischer CN, Trautman EP, Crawford JM, Stabb E, Handelsman J, Broderick NA. Metabolite exchange between microbiome members produces compounds that influence Drosophila behavior. eLife. 2017;6:e18855. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18855.001.

Saldana MA, Hegde S, Hughes GL. Microbial control of arthropod-borne disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. 2017;112:81–93. https://doi.org/10.1590/0074-02760160373.

Gao H, Cui C, Wang L, Jacobs-Lorena M, Wang S. Mosquito microbiota and implications for disease control. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36:98–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2019.12.001.

Briones-Roblero CI, Hernandez-Garcia JA, Gonzalez-Escobedo R, Soto-Robles LV, Rivera-Orduna FN, Zuniga G. Structure and dynamics of the gut bacterial microbiota of the bark beetle, Dendroctonus rhizophagus (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) across their life stages. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0175470. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175470.

Medina F, Li H, Vinson SB, Coates CJ. Genetic transformation of midgut bacteria from the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta). Curr Microbiol. 2009;58:478–82.

Muhammad A, Fang Y, Hou Y, Shi Z. The Gut Entomotype of Red Palm Weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Olivier (Coleoptera: Dryophthoridae) and their effect on host nutrition metabolism. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2291. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02291.

Renoz F, Noel C, Errachid A, Foray V, Hance T. Infection dynamic of symbiotic bacteria in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum gut and host immune response at the early steps in the infection process. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0122099.

Wang A, Yao Z, Zheng W, Zhang H. Bacterial communities in the gut and reproductive organs of Bactrocera minax (Diptera: Tephritidae) based on 454 pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e106988. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106988.

Lin X-L, Pan Q-J, Tian H-G, Douglas AE, Liu T-X. Bacteria abundance and diversity of different life stages of Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae), revealed by bacteria culture-dependent and PCR-DGGE methods. Insect Sci. 2015;22:375–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.12079

Gumiel M, da Mota FF, Rizzo V, de S, Sarquis O, de Castro DP, et al. Characterization of the microbiota in the guts of Triatoma brasiliensis and Triatoma pseudomaculata infected by Trypanosoma cruzi in natural conditions using culture independent methods. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:245. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0836-z.

Gupta AK, Rastogi G, Nayduch D, Sawant SS, Bhonde RR, Shouche YS. Molecular phylogenetic profiling of gut-associated bacteria in larvae and adults of flesh flies. Med Vet Entomol. 2014;28:345–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/mve.12054.

da Mota FF, Marinho LP, Moreira CJ, de C, Lima MM, Mello CB, et al. Cultivation-independent methods reveal differences among bacterial gut microbiota in triatomine vectors of Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1631. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001631.

Kelly PH, Bahr SM, Serafim TD, Ajami NJ, Petrosino JF, Meneses C, et al. The gut microbiome of the vector Lutzomyia longipalpisIs essential for survival of Leishmania infantum. MBio. 2017;8:e01121–16. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01121-16.

Vieira CS, Waniek PJ, Castro DP, Mattos DP, Moreira OC, Azambuja P. Impact of Trypanosoma cruzi on antimicrobial peptide gene expression and activity in the fat body and midgut of Rhodnius prolixus. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1398-4.

Zink S, Van Slyke G, Palumbo M, Kramer L, Ciota A. Exposure to West Nile virus increases bacterial diversity and immune gene expression in Culex pipiens. Viruses. 2015;7:5619–31. https://doi.org/10.3390/v7102886.

Thongsripong P, Chandler JA, Green AB, Kittayapong P, Wilcox BA, Kapan DD, et al. Mosquito vector‐associated microbiota: metabarcoding bacteria and eukaryotic symbionts across habitat types in Thailand endemic for dengue and other arthropod‐borne diseases. Ecol Evolution. 2017;16:118. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3676.

Seitz HM, Maier WA, Rottok M, Becker-Feldmann H. Concomitant infections of Anopheles stephensi with Plasmodium berghei and Serratia marcescens: additive detrimental effects. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A. 1987;266:155–66.

Muturi EJ, Bara JJ, Rooney AP, Hansen AK. Midgut fungal and bacterial microbiota of Aedes triseriatus and Aedes japonicus shift in response to La Crosse virus infection. Mol Ecol. 2016;25:4075–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13741.

Bennett KL, Gómez-Martínez C, Chin Y, Saltonstall K, McMillan WO, Rovira JR, et al. Dynamics and diversity of bacteria associated with the disease vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12160–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48414-8.

Dickson LB, Jiolle D, Minard G, Moltini-Conclois I, Volant S, Ghozlane A, et al. Carryover effects of larval exposure to different environmental bacteria drive adult trait variation in a mosquito vector. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1700585. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700585.

Zouache K, Raharimalala FN, Raquin V, Tran-Van V, Raveloson LHR, Ravelonandro P, et al. Bacterial diversity of field-caught mosquitoes, Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti, from different geographic regions of Madagascar. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.01012.x.

Dickson LB, Ghozlane A, Volant S, Bouchier C, Ma L, Vega-Rua A, et al. Diverse laboratory colonies of Aedes aegypti harbor the same adult midgut bacterial microbiome. Parasit Vectors. 2018;3:e1700585. https://doi.org/10.1101/200659.

David MR, Santos LMBD, Vicente ACP, Maciel-de-Freitas R. Effects of environment, dietary regime and ageing on the dengue vector microbiota: evidence of a core microbiota throughout Aedes aegypti lifespan. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2016;111:577–87. https://doi.org/10.1590/0074-02760160238.

de O, Gaio A, Gusmão DS, Santos AV, Berbert-Molina MA, Pimenta PF, et al. Contribution of midgut bacteria to blood digestion and egg production in Aedes aegypti (diptera: culicidae) (L.). Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:105. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-4-105.

Gusmão DS, Santos AV, Marini DC, Russo E, de S, Peixoto AMD, et al. First isolation of microorganisms from the gut diverticulum of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae): new perspectives for an insect-bacteria association. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:919–24.

Gusmão DS, Santos AV, Marini DC, Bacci M, Berbert-Molina MA, Lemos FJA. Culture-dependent and culture-independent characterization of microorganisms associated with Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) (L.) and dynamics of bacterial colonization in the midgut. Acta Trop. 2010;115:275–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.04.011.

Coon KL, Vogel KJ, Brown MR, Strand MR. Mosquitoes rely on their gut microbiota for development. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:2727–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12771.

Kozlova EV, Khajanchi BK, Sha J, Chopra AK. Quorum sensing and c-di-GMP-dependent alterations in gene transcripts and virulence-associated phenotypes in a clinical isolate of Aeromonas hydrophila. Micro Pathog. 2011;50:213–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2011.01.007.

Rose WA, McGowin CL, Spagnuolo RA, Eaves-Pyles TD, Popov VL, Pyles RB. Commensal bacteria modulate innate immune responses of vaginal epithelial cell multilayer cultures. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e32728. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032728.

Kozlova EV, Khajanchi BK, Popov VL, Wen J, Chopra AK. Impact of QseBC system in c-di-GMP-dependent quorum sensing regulatory network in a clinical isolate SSU of Aeromonas hydrophila. Micro Pathog. 2012;53:115–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2012.05.008.

Williams RP, Gott CL. Inhibition by streptomycin of the biosynthesis of prodigiosin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1964;16:47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-291X(64)90209-8.

Jeffries CL, Lawrence GG, Golovko G, Kristan M, Orsborne J, Spence K, et al. Novel Wolbachia strains in Anopheles malaria vectors from Sub-Saharan Africa. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:113. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14765.2.

Tourlousse DM, Yoshiike S, Ohashi A, Matsukura S, Noda N, Sekiguchi Y. Synthetic spike-in standards for high-throughput 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e23. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw984.

Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, Peplies J, Quast C, Horn M. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41:e1.

Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1219.

Mandal S, Van Treuren W, White RA, Eggesbø M, Knight R, Peddada SD. Analysis of composition of microbiomes: a novel method for studying microbial composition. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:1–7. https://doi.org/10.3402/mehd.v26.27663.

Zhu H, Sun S-J, Dang H-Y. PCR detection of Serratia spp. using primers targeting pfs and luxS genes involved in AI-2-dependent quorum sensing. Curr Microbiol. 2008;57:326–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-008-9197-6.

Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13:e1005595. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352

Kinosita Y, Kikuchi Y, Mikami N, Nakane D, Nishizaka T. Unforeseen swimming and gliding mode of an insect gut symbiont, Burkholderia sp. RPE64, with wrapping of the flagella around its cell body. ISME J. 2018;12:838–48. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-017-0010-z.

Wiles TJ, Schlomann BH, Wall ES, Betancourt R, Parthasarathy R, Guillemin K. Swimming motility of a gut bacterial symbiont promotes resistance to intestinal expulsion and enhances inflammation. PLoS Biol. 2020;18:e3000661. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000661.

Bando H, Okado K, Guelbeogo WM, Badolo A, Aonuma H, Nelson B, et al. Intra-specific diversity of Serratia marcescens in Anopheles mosquito midgut defines Plasmodium transmission capacity. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1641–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01641.

Abreo E, Altier N. Pangenome of Serratia marcescens strains from nosocomial and environmental origins reveals different populations and the links between them. Sci Rep. 2019;9:46–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37118-0.

Chavda KD, Chen L, Fouts DE, Sutton G, Brinkac L, Jenkins SG, et al. Comprehensive genome analysis of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter spp.: new insights into phylogeny, population structure, and resistance mechanisms. MBio. 2016;7. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02093-16.

Wyres KL, Lam MMC, Holt KE. Population genomics of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat Rev Micro. 2020;66:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-019-0315-1.

Pumpuni CB, Demaio J, Kent M, Davis JR, Beier JC. Bacterial population dynamics in three anopheline species: the impact on Plasmodium sporogonic development. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;54:214–8.

Wang Y, Gilbreath TM III, Kukutla P, Yan G, Xu J. Dynamic gut microbiome across life history of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24767. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024767.

Wang S, Ghosh AK, Bongio N, Stebbings KA, Lampe DJ, Jacobs-Lorena M. Fighting malaria with engineered symbiotic bacteria from vector mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12734–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1204158109.

Bai L, Wang L, Vega-Rodriguez J, Wang G, Wang S. A Gut Symbiotic Bacterium Serratia marcescens renders mosquito resistance to plasmodium infection through activation of mosquito immune responses. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1580. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01580.

Muturi EJ, Dunlap C, Ramirez JL, Rooney AP, Kim C-H. Host blood-meal source has a strong impact on gut microbiota of Aedes aegypti. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2019;95. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiy213.

Yao Z, Wang A, Li Y, Cai Z, Lemaitre B, Zhang H. The dual oxidase gene BdDuox regulates the intestinal bacterial community homeostasis of Bactrocera dorsalis. ISME J. 2016;10:1037–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.202.

Andersen K, Kesper MS, Marschner JA, Konrad L, Ryu M, SK VR, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis, barrier dysfunction, and bacterial translocation account for CKD–related systemic inflammation. JASN. 2017;28:76–83. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2015111285.

Schaubeck M, Clavel T, Calasan J, Lagkouvardos I, Haange SB, Jehmlich N, et al. Dysbiotic gut microbiota causes transmissible Crohn’s disease-like ileitis independent of failure in antimicrobial defence. Gut. 2016;65:225–37. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309333.

Peng W, Huang J, Yang J, Zhang Z, Yu R, Fayyaz S, et al. Integrated 16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomics, and metabolomics to characterize gut microbial composition, function, and fecal metabolic phenotype in non-obese type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:3141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.03141.

Li F, Wang P, Chen Z, Sui X, Xie X, Zhang J. Alteration of the fecal microbiota in North-Eastern Han Chinese population with sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2019;707:134297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134297

Hegde S, Voronin D, Casas-Sanchez A, Saldaña M, Acosta-Serrano A, Popov VL, et al. Gut-associated bacteria invade the midgut epithelium of Aedes aegypti and stimulate innate immunity and suppress Zika virus infection in cells. bioRxiv. 2019;37:866897. https://doi.org/10.1101/866897.

Xi Z, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. The Aedes aegypti toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000098–49.

Ramirez JL, Souza-Neto J, Torres Cosme R, Rovira J, Ortiz A, Pascale JM, et al. Reciprocal tripartite interactions between the Aedes aegypti midgut microbiota, innate immune system and dengue virus influences vector competence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1561. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001561.

Koosha M, Vatandoost H, Karimian F, Choubdar N, Abai MR, Oshaghi MA. Effect of Serratia AS1 (Enterobacteriaceae: Enterobacteriales) on the fitness of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) for paratransgenic and RNAi approaches. J Med Entomol. 2019;56:553–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjy183.

Adair KL, Bost A, Bueno E, Kaunisto S, Kortet R, Peters-Schulze G, et al. Host determinants of among-species variation in microbiome composition in drosophilid flies. ISME J. 2020;14:217–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-019-0532-7.

Early AM, Shanmugarajah N, Buchon N, Clark AG. Drosophila genotype influences commensal bacterial levels. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0170332–15.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the UTMB insectary core for providing mosquitoes and Alvaro Acosta-Serrano for commenting on a previous draft. GLH was supported by the BBSRC (BB/T001240/1), the Royal Society Wolfson Fellowship (RSWF\R1\180013), NIH grants (R21AI124452 and R21AI129507), the Western Gulf Center of Excellence for Vector-borne Diseases (CDC grant CK17-005), UKRI (20197), and the NIHR (NIHR2000907). GLH is affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at University of Liverpool in partnership with Public Health England (PHE), in collaboration with Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the University of Oxford. GLH is based at LSTM. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health or Public Health England. GLH and EH are also jointly funded by the BBSRC (V011278/1). This work was also supported by a James W. McLaughlin postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Texas Medical Branch and a Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine Director’s Catalyst Fund award to SH, and a NIH T32 fellowship (2T32AI007526) to MAS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kozlova, E.V., Hegde, S., Roundy, C.M. et al. Microbial interactions in the mosquito gut determine Serratia colonization and blood-feeding propensity. ISME J 15, 93–108 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00763-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00763-3

This article is cited by

-

Interkingdom interactions shape the fungal microbiome of mosquitoes

Animal Microbiome (2024)

-

Wolbachia dominance influences the Culex quinquefasciatus microbiota

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Holobiont perspectives on tripartite interactions among microbiota, mosquitoes, and pathogens

The ISME Journal (2023)

-

Overview of paratransgenesis as a strategy to control pathogen transmission by insect vectors

Parasites & Vectors (2022)

-

Interspecies microbiome transplantation recapitulates microbial acquisition in mosquitoes

Microbiome (2022)