Abstract

Mutualisms between symbiotic microbes and animals have been well documented, and nutritional relationships provide the foundation for maintaining beneficial associations. The well-studied mutualism between bark beetles and their fungi has become a classic model system in the study of symbioses. Despite the nutritional competition between bark beetles and beneficial fungi in the same niche due to poor nutritional feeding substrates, bark beetles still maintain mutualistic associations with beneficial fungi over time. The mechanism behind this phenomenon, however, remains largely unknown. Here, we demonstrated the bark beetle Dendroctonus valens LeConte relies on the symbiotic bacterial volatile ammonia, as a nitrogen source, to regulate carbohydrate metabolism of its mutualistic fungus Leptographium procerum to alleviate nutritional competition, thereby maintaining the stability of the bark beetle–fungus mutualism. Ammonia significantly reduces competition of L. procerum for carbon resources for D. valens larval growth and increases fungal growth. Using stable isotope analysis, we show the fungus breakdown of phloem starch into d-glucose by switching on amylase genes only in the presence of ammonia. Deletion of amylase genes interferes with the conversion of starch to glucose. The acceleration of carbohydrate consumption and the conversion of starch into glucose benefit this invasive beetle–fungus complex. The nutrient consumption–compensation strategy mediated by tripartite beetle–fungus–bacterium aids the maintenance of this invasive mutualism under limited nutritional conditions, exacerbating its invasiveness with this competitive nutritional edge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mutualistic associations between symbiotic microbes and animals are pervasive in every ecosystem [1,2,3,4,5], where they commonly compete with intraspecific and interspecific species within the host-provided environment [6,7,8]. These competitors include vector insects, other insects and coexisting microorganisms. Some specialist insects feed on nutrient-deficient food that experience particularly severe competition with their symbiotic microbes [9, 10]. Bark beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) are major economic and ecological pests in forest ecosystems that feed within nutritionally poor substrates including woody tissues, bark, phloem, and the pith of twigs [11, 12]. Most bark beetles vector symbiotic fungi that coexist with a multitude of microbes [12,13,14,15,16]. Bark beetle–fungi interactions have been classified as mutualistic, antagonistic, and commensal [12, 14]. Mutualistic fungi are often pathogenic to the host plant, facilitating their vector’s survival in living or newly killed plant tissues until the defenses subside [10]. Some mutualistic fungi also can induce the release of attractive volatiles from infected host trees, and these volatiles can facilitate aggregation of bark beetles on host trees [17]. Bark beetles associated with mutualistic fungi grow faster, have larger body size and their progeny suffer lower mortality [9, 18,19,20,21]. Meanwhile, fungi benefit from the mutualistic association by being vectored to otherwise inaccessible plant resources [19, 22]. However, the phloem that they consume has a low nutritional value relative to their requirements [21, 22], and it remains elusive exactly how these insects maintain mutualistic associations with beneficial symbionts under nutritional stress.

Nutritional contribution of beneficial symbionts has a critical role in maintaining the stability of the mutualism [9, 21, 23,24,25,26]. One well-studied insect-beneficial symbiosis is the interaction between aphids and their primary symbiont, Buchnera, which provides essential amino acids for its insect host [23, 27]. Similarly, genomic analysis of the obligate flavobacterial endosymbiont, Blattabacterium of Periplaneta americana also revealed that Blattabacterium were able to synthesize and provide all essential amino acids for P. americana [28]. In mosquitoes, gut microbiota mediate lipid absorption via the hypoxia pathway [25]. However, while these previous studies have extensively studied endosymbiotic and intestinal bacteria, little is known about the role of external microbes in contributing to nutrition. For nutritional deficiency in beetle–fungus symbioses, some symbiotic fungi serve as important food resources for the developing larvae to reduce nutritional challenges for beetles [19, 29]. In addition, some symbiotic fungi may expand the capacity of beetles to use nutrient-poor plant resources. For example, most plant tissues have relatively low levels of nitrogen and sterols, and the beetles’ mutualistic fungi benefit larval growth by concentrating nitrogen or producing sterols in phloem tissue where feeding occurs [9, 30]. For carbohydrates, however, mutualistic fungi compete with beetles for this resource leading to reduced larval growth [31]. In addition, antagonistic fungi also compete for the same carbohydrates, which reduced the stability of bark beetle–fungus mutualisms [10, 31, 32].

Carbohydrates are essential nutrients that provide energy and precursors for tissue building during bark beetle and fungi development [33]. Competition for this resource inevitably affects the stability of beetle–fungus mutualisms. Symbiotic bacteria of insects have been reported to have a stabilizing effect on the maintenance of insect–fungus mutualisms [1, 2], e.g., bark beetle-associated bacteria limited the growth and reproduction of symbiotic fungi [34,35,36]. Symbiotic actinomycetous bacteria can protect the beetle–fungus mutualism by producing antibiotics, which selectively inhibit antagonistic fungi [2]. However, only a few studies have focused on the effects of symbiotic bacteria on the bark beetle–fungus mutualism from the perspective of nutrition. The bacteria-released volatile, ammonia, has been found to be a regulator of the beetle–fungus mutualism and exposure to ammonia affected the symbiotic fungus’ growth and monosaccharides consumption, thereby contributing to the maintenance of the mutualistic community [37]. However, the underlying mechanisms behind how the volatile ammonia, which is produced by the beetle’s symbiotic bacteria, actually help them preserve the persistence of beneficial fungi through regulation of the fungus’ carbohydrate consumption, remains largely unknown. Previous studies show transcriptional regulators appeared to integrate control of both carbon and nitrogen metabolism in filamentous fungi [38,39,40].

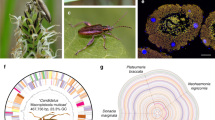

Red turpentine beetle (RTB), Dendroctonus valens LeConte, native to North America, is a destructive invasive pest in China. It feeds on nutrient-poor phloem of the pine tree Pinus tabuliformis Carrière, causing extensive pine mortality in China [41]. The beetles are commonly associated with various ophiostomatoid fungi including Leptographium procerum and Ophiostoma minus, which coexist with a multitude of microbes [42, 43]. These fungal species were found in pits and on setae on their body surfaces and frass [42]. L. procerum is the most frequently isolated species from RTB and forms a tightly mutualistic beetle–fungus invasive complex, thereby contributing to RTB’s successful invasiveness in China [17, 42, 44]. However, this invasive complex faces a particularly severe challenge because the phloem that they consume is nutritionally poor (containing nitrogen-limited sources, recalcitrant carbohydrate sources, and plant defensive compounds) [9, 37]. Nitrogen concentrations (% dry weight) of P. tabuliformis and Pinus taeda phloem are 0.66% and 0.4%, respectively, whereas the nitrogen concentrations of fungal and insect tissues are in the ranges 1.5–7% and 8–13%, respectively [9, 37]. Bacteria associated with beetles cope with nitrogen limitation by recycling nitrogen from beetle excretions or fixing atmospheric nitrogen (N2) [9, 45, 46]. Carbon is in fact not limited but bound to polysaccharides in cellulose and starch, while easily accessible monosaccharides for RTB and its associated microbes are limited [31, 37]. RTB larval growth is drastically inhibited by competition over saccharides from L. procerum and some other fungi [31]. Further investigations revealed that three species of bacteria associated with RTB larvae (Serratia liquefaciens B310, Rahnella aquatilis B301, and Pseudomonas sp. 7 B321) produced the bacterial volatile ammonia, and experimentally adding ammonium eliminated the negative effects caused by symbiotic fungi on RTB larval growth [37]. In addition, associated bacterial volatiles inhibited the growth of antagonistic fungi O. minus, but had no effect on the growth of mutualistic fungi L. procerum by regulating monosaccharides consumption [37, 47]. All of these results demonstrated that the nitrogenous volatile ammonia released by several mutualistic bacterial strains apparently alleviate the nutritional competition for monosaccharides (i.e., d-glucose) between larvae and fungi [31, 37]. In this study, in order to elucidate the underlying mechanisms upon which a cryptic insect maintain mutualistic associations with beneficial symbionts under poor nutritional conditions, we examined the D. valens–L. procerum mutualism as a model. Results showed that the associated bacterial volatile ammonia, as a nitrogen source, regulates the mutualistic fungus L. procerum’s monosaccharide consumption and starch metabolism pathway that optimizes both the mutualistic fungus’ growth and larval development of RTB. We speculated that this is a strategy that helps maintain mutualistic associations with beneficial symbionts for insects in substrates with limited nutrition.

Materials and methods

Fungal strains and maintenance

The fungal strain L. procerum CMW25626, commonly associated with RTB and reported as a mutualistic fungal associate for RTB larvae, was used [17, 42]. The strain was cultured as previously described [31]. Escherichia coli DH5a bacterial strain was used for plasmid construction. Agrobactium tumefaciens AGL1 strain was used for fungal transformation [48].

Ammonia, ammonium, and fungal growth in the phloem medium

Cultures of L. procerum were grown and maintained on 2% malt extract agar medium (MEA: 2 g malt extract, 2 g agar, and 100 mL purified distilled water). Phloem medium was prepared to examine the effects of ammonia and ammonium on the growth rate, dry weight, and density of L. procerum. The ammonia concentration measured in bacterial Luria–Bertani (LB) cultures and the effects of the serial dilution of ammonia water solution on growth and carbon source usage in L. procerum indicated that the regulation of ammonia and ammonium is concentration-dependent [37]. Medium preparation and experiments were performed as described in the Supplementary Methods.

Ammonia, ammonium, and D. valens larval growth in the phloem medium

The effects of ammonia and ammonium on larval growth by L. procerum were determined using a phloem-medium method. The phloem medium was poured into petri dishes as described above. Experiments were performed as described in the Supplementary Methods.

Effects of ammonium on carbohydrate composition in desugared phloem medium after L. procerum growth at different time points

In this experiment, in order to eliminate the effects of other carbohydrates and to show that the system is indeed carbon-limited in nature, we used desugared phloem medium, instead of standard phloem medium, to study the effects of ammonium on specific carbohydrate composition, then analyzed L. procerum growth at different time points. Medium preparation and experiments were performed as described in the Supplementary Methods.

13C6-labeled glucose treatment

In order to investigate the dynamics of glucose in the medium, a stable isotope of glucose (d-glucose-13C6) was utilized, and its concentration in the medium was measured by GC/MS. A total of 200 mg of d-glucose and d-glucose-13C6 standard aqueous solution (2 g/mL) was sampled and analyzed to obtain mass spectra with GC/MS [37]. To further clarify the source of the remaining glucose in the medium, d-glucose-13C6 1 g/L and d-pinitol 1 g/L were added to desugared phloem medium. Particularly, the medium with ammonium was set as treatment and medium without ammonium was set as control. The desugared phloem medium with fungus was sampled on day 5 after the inoculation of fungus, and carbohydrate composition was measured [37]. An additional treatment with only d-pinitol 1 g/L added to desugared phloem was also analyzed using the same methods. For each treatment, eight biological replicates were used.

Carbohydrate analysis

The carbohydrate content in phloem related to glucogenesis was extracted and analyzed. The starch was ground up determined using EnzyChrom Starch Assay Kit (BioAssay Systems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the starch extraction, we ground up 5 mg phloem, phloem medium and desugared phloem sample, and washed off any free glucose and small oligosaccharides with 1 mL 90% ethanol, then warmed it to 60 °C for extraction and analysis. Other polymers like pectin, xylan, and lignin that do not break up in d-glucose were not analyzed. The other carbohydrates, including sucrose, maltose, and trehalose, were also extracted and analyzed [37]. Eight replicates were used.

RNA-seq analyses and qRT-PCR analysis

RNA extractions, RNA-seq analyses, cDNA synthesis, and qRT-PCR were performed as described in the Supplementary Methods. Three biological replicates were used for both RNA-sequence and qRT-PCR. The primers used here are included in Supplementary Table S1.

Enzymatic activity

The enzymatic activities of the α-amylase, amyloglucosidase, and α-glucosidase of the fungus were measured using the corresponding model substrates (three replicates per treatment). Enzymes were extracted from fungi from three petri dishes in a centrifuge tube containing 1 mL of ice-cold PBS buffer (0.1 mol−1, pH = 7.4) [49]. The homogenate was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C and the resulting supernatant was used directly for spectrophotometric assays of AMYA, AMYG, and α-GLU activities. The activities of α-amylase, amyloglucosidase were determined using commercial ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) kits (Jiangsu Yutong Biological Technology Co., Ltd, Jiangsu, China), and α-glucosidase was measured by a commercial ELISA kit (Shanghai MLBIO Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China).

Confirmation of starch as carbon source for d-glucose using minimal medium

The standard minimal medium was made as follows: 1 g of KH2PO4, 0.5 g of MgSO4·7H2O, 0.02 g of FeSO4·7H2O, 0.02 g of ZnCl2, 0.01 g of MnCl2, 0.01 g of Pyridoxine, and 25 g of Difco Bacto agar were dissolved into 1 L of distilled water. To further confirm the conversion of starch to glucose, 1 g of d-pinitol was added into the standard minimal medium. In addition to d-pinitol, either 20 g of starch, 20 g of cellulose, or 1 g of sucrose was also individually added to rule out their possible conversion to glucose. Eight biological replicates were used. For investigating the effects of d-glucose and starch on the growth of L. procerum and RTB larvae, 0.4% (w/v) of starch or d-glucose was added into standard minimal medium, respectively. pH of these media was adjusted to 6.0 ± 0.1 with 1 N KOH or 1 N H2SO4 before autoclaving (30 min, 120 °C, 0.14 Mpa). To ensure enough valid biological replicates, n = 32 was used.

Gene knockout in L. procerum

Gene deletions of SUC1, AMYG, and AMYA3 were performed by homologous recombination [50, 51], as described in the Supplementary Methods. The primers used here are included in Supplementary Table S1.

Results

Ammonia, ammonium, and fungal growth

Laboratory-based experiments compared the presence or absence of ammonia/ammonium within the phloem medium with the growth performance of L. procerum. Ammonia/ammonium significantly promoted the growth of L. procerum. The spore and mycelium densities of L. procerum revealed that ammonia/ammonium exposure significantly increased the growth of L. procerum (Fig. 1a, b). The fungal growth rate was 109.0%, and 107.0% compared with the control at doses of 1.56 mol/L ammonia and 0.019 mol/L ammonium, respectively (Fig. 1c, d) (df = 35.241, t = −17.330, P < 0.001; df = 38, t = −12.403, P < 0.001 t-test). The activity on fungal growth by ammonia (1.56 mol/L) and ammonium (0.019 mol/L) was determined using the fungal biomass yield method. After 13 days, the fungal biomass yield with ammonia/ammonium (14.58 mg [dry weight] petri−1/27.30 mg [dry weight] petri−1) was significantly greater than that with sterile water (1.73 mg [dry weight] petri−1/4.60 mg [dry weight] petri−1) (Fig. 1e, f) (df = 7.223, t = 14.748, P < 0.001; df = 9.32, t = 13.213, P < 0.001 t-test).

Representative growth of L. procerum on phloem medium infused with ammonia (a) and ammonium (b), respectively (Top: Low-magnification images; Bottom: High-magnification images of samples from day 13). Effects of exposure of ammonia (c) and ammonium (d) on the growth of L. procerum. Effects of exposure of ammonia (e) and ammonium (f) on the dry weight of L. procerum. Error bars of c–f represent SEs of at least eight biological replicates. Asterisk indicates significant difference between treatment and control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NS means no significance.

Ammonia, ammonium, and D. valens larval growth

We observed no significant difference in weight change of RTB larvae in phloem media with or without ammonia (1.56 mol/L)/ammonium (0.019 mol/L) (Fig. 2a) (F2, 66 = 2.163, P = 0.124 ANOVA, Dunnett’s test). Bioassays using the phloem medium infused with 1.56 mol/L ammonia or 1 g/L ammonium characterized the effects of ammonia and ammonium on RTB larval growth by L. procerum. RTB larval weight decreased significantly on L. procerum-colonized phloem media compared to fungus-free phloem media. The weight of RTB larvae fed with phloem media colonized by L. procerum with ammonia (1.56 mol/L)/ammonium (0.019 mol/L) presented were significantly higher compared to those with sterile water. In addition, no significant difference was noted between ammonia and ammonium treatments (Fig. 2b) (F3, 80 = 24.865, P < 0.0001 ANOVA, Dunnett’s test).

(a) Effects of exposure of ammonia and ammonium on the weight change of RTB. (b) Effects of exposure of ammonia and ammonium on the weight change of RTB with the present of L. procerum. Error bars represent SEs of at least 20 biological replicates. Asterisk indicates significant difference between treatment and control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NS means no significance.

Ammonium and carbohydrate consumption

Previously, we determined that ammonia can regulate L. procerum consumption sequence of d-pinitol and d-glucose in phloem medium but it did not affect the consumption of other carbohydrates [37]. Here, we verified the same result that ammonium can regulate the L. procerum consumption of d-pinitol and d-glucose using desugared phloem medium (adding 1 g/L of d-glucose and d-pinitol) (Supplementary Fig. S1) [37]. Compared to the untreated control cultures, the marked reduction in d-pinitol began earlier than d-glucose. d-glucose started to decline significantly on the 5th day in plates colonized by L. procerum without the ammonium, and was depleted on the 11th day. However, the content of d-pinitol stayed constant before the 7th day and 38.65% remained on the 11th day (Supplementary Fig. S1a) (d-pinitol: F9, 70 = 462.667, P < 0.001 ANOVA, Tukey’s test; d-glucose: F9, 70 = 1057.377, P < 0.001 ANOVA, Dunnett’s T3 test). In presence of ammonium, d-pinitol in plates colonized by L. procerum started to decline significantly on the 5th day and was used up on the 11th day, and 51.25% d-glucose remained in plates on the 11th day (Supplementary Fig. S1b) (d-pinitol: F9, 70 = 652.753, P < 0.001; d-glucose: F9, 70 = 97.468, P < 0.001 ANOVA, Dunnett’s T3 test). Ammonia and ammonium reduced inhibition of L. procerum on RTB larval growth and increased fungal growth by regulating d-glucose and d-pinitol consumption in the fungus (Figs. 1 and 2). Obviously, d-glucose was a readily available and preferred carbon source for L. procerum compared to d-pinitol [45]. In order to further confirm the relationship between the carbohydrates consumption by the fungus and the fungal growth in the presence of ammonium, we analyzed the carbohydrate composition of the desugared phloem medium (adding 1 g/L, d-glucose and d-pinitol) in L. procerum-colonized area as the fungus grew over time. Without the ammonium, the d-glucose and d-pinitol consumption by the fungus was similar to the whole desugared phloem medium and fungi-colonized area of the desugared phloem medium (Fig. 3a) (d-pinitol: F9, 70 = 628.211, P < 0.001; d-glucose: F9, 70 = 760.623, P < 0.001 ANOVA, Dunnett’s T3 test). With the presence of ammonium, d-pinitol also decreased significantly over time in plates colonized by L. procerum. On the other hand, the content of d-glucose in L. procerum-colonized area initially decreased sharply and then increased to its peak on day 5, and then decreased with time (Fig. 3b) (d-pinitol: F9, 70 = 564.548, P < 0.001 ANOVA, Dunnett’s T3 test; d-glucose: F9, 70 = 103.886, P < 0.001 ANOVA, Tukey’s test). Given these findings, we initially speculated that ammonia and ammonium do not affect d-glucose consumption by L. procerum and d-glucose left in the medium that originated from conversion from other substances.

Carbohydrate composition in L. procerum-colonized area of desugared phloem media at different time points without (a) and with (b) ammonium. Error bars represent SEs of at least eight biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences among different treatments (P < 0.05). NS means no significance.

13C6-labeled glucose treatment

The mass spectra of d-glucose and d-glucose-13C6 standards were shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. On the basis of the mass spectra for d-glucose and d-glucose-13C6, we decided to consider the ions m/z 319 and m/z 323, which have large mass numbers and relatively high intensities, as monitor ions. Without ammonium, there was no difference in the concentration of natural glucose between fungus-free and the fungus-colonized medium, and the concentration of labeled glucose significantly decreased in fungus-colonized medium when compared to the fungus-free medium (Fig. 4a, b) (m/z 319: df = 14, t = 1.110, P = 0.293; m/z 323: df = 5.686, t = 22.951, P < 0.001 t-test). In the presence of ammonium, the concentration of natural glucose increased and the labeled glucose was depleted on the fungus-colonized medium compared to the fungus-free medium (Fig. 4b, c) (m/z 319: df = 11, t = −8.309, P < 0.001; m/z 323: df = 7.035, t = 114.821, P < 0.001 t-test). Compared to the control, labeled glucose was also consumed faster by the fungus in the presence of ammonium (Fig. 4). Even with desugared phloem medium only supplied with d-pinitol (1 g/L), the production of glucose was detected in L. procerum-colonized phloem media in the presence of ammonium (Supplementary Fig. S3a, b). However, when ammonium was absent, no glucose was found in L. procerum-colonized phloem media (Supplementary Fig. S3a, b). Furthermore, in the L. procerum-colonized minimal medium (glucose-free medium with only 1 g/L d-pinitol added), no glucose was produced in either the presence or absence of ammonium (Supplementary Fig. S3c).

Carbohydrate composition in L. procerum-colonized area of desugared phloem media at day 5 without (a) and with (c) ammonium. (b) GC–MS traces of natural glucose and 13C6-labeled glucose. Error bars of (a) and (c) represent SEs of eight biological replicates. Asterisk indicates significant difference between fungus and fungus-free (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NS means no significance.

Carbohydrate analysis

The preceding results indicated that ammonium exposure caused the conversion of phloem substances to glucose in L. procerum. Thus, we subsequently analyzed the content of glucogenesis-related substances in the phloem. It is well known that pine phloem is rich in cellulose [38]. Other carbohydrates related to glucogenesis in Pinus tabuliformis phloem were extracted and analyzed. Starch and sucrose were the only carbohydrates related to glucogenesis detected in the phloem (Table 1). All sample preparations from the phloem (311.87 ± 17.08 mg/g, DW), the phloem medium (236.72 ± 7.03 mg/g, DW) and the desugared phloem (258.61 ± 4.46 mg/g, DW) contained relatively high percentages of starch. Very small amounts of sucrose were present in the sample preparations from the phloem (1.65 ± 0.06 mg/g, DW) and the phloem medium (2.20 ± 0.13 mg/g, DW), and it was not detected in the preparations from the desugared phloem.

No glucose was produced in the L. procerum-colonized minimal medium (adding 1 g/L d-pinitol) despite the presence or absence of ammonium (Supplementary Fig. S3c). However, in the minimal medium supplemented with 1 g/L d-pinitol and 20 g/L starch, glucose was detected only in the L. procerum-colonized minimal medium with the addition of starch in the presence of ammonium (Fig. 5a, b) (d-glucose: df = 6, t = −18.630, P < 0.001 t-test). In addition, after introducing two other glucogenesis-related carbohydrates (cellulose and sucrose) to the minimal medium (adding 1 g/L d-pinitol), there was still no glucose detected in the minimal medium in the presence of ammonium (Supplementary Fig. S4). Further investigation revealed that L. procerum and RTB larvae performed better on minimal media with glucose than that on minimal media with only starch (Supplementary Fig. S5) (df = 42, t = 2.957, P = 0.008 t-test). All of these results indicated that starch is the only substance in phloem available for the production of glucose, and L. procerum is able to convert the nutrient-poor but abundant carbohydrate (starch) into a highly nutritional carbon source (glucose).

Carbohydrate composition in L. procerum-colonized area of minimal media with starch and d-pinitol at day 5 without (a) and with (b) ammonium. Error bars represent SEs of eight biological replicates. Asterisk indicates significant difference between fungus and fungus-free (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NS means no significance.

The bacterial volatile ammonia, as a nitrogen source, induces the L. procerum starch metabolism pathway to convert starch to high nutritional-value glucose

As evidenced that starch is responsible for the production of glucose by L. procerum, we then used next generation sequencing to determine which gene was involved in this process (Fig. 6a). Genes for hydrolyzing starch to glucose/digestion of starch, including α-amylase (AMYA3), which is involved in the breakdown of long chain carbohydrates, amyloglucanase (AMYG) and α-glucosidase (α-glu1 and α-glu5), which are involved in breaking down starch to the monosaccharide glucose, were upregulated by the exposure of ammonium (Fig. 6b). Other genes related to cellulose and sucrose metabolism showed no response to ammonium exposure (Supplementary Fig. S6). qRT-PCR analyses also found that exposure to ammonium significantly induced the expression of AMYA3, AMYG and α-glu5 (Fig. 6c) (AMYG: df = 4, t = −8.402, P < 0.001; AMYA3: df = 4, t = −4.693, P < 0.001; α-glu5: df = 4, t = −5.618, P = 0.005; α-glu6: df = 4, t = 0.288, P = 0.787; α-glu1: df = 4, t = −1.247, P = 0.280 t-test).

(a) Schematic showing key components of the conversion of starch to glucose. (b) Heatmap of genes for hydrolyzing starch to glucose/the digestion of starch at different time point. Asterisk (*) indicated that an absolute value of log2Ratio ≥ 1 and FDR < 0.05. (c) qRT-PCR validation. All tested samples were collected at day 5. (d) Enzymatic activities of amylolytic enzymes. Asterisk of (c) and (d) indicates significant difference between control and NH4Cl treatment (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NS means no significance. Error bars of (c) and (d) represent SEs of three biological replicates.

Besides the expression of these genes, we also measured the enzymatic activity of α-amylase, amyloglucanase, and α-glucosidase by double antibody sandwich methods. Compared to the control, ammonium-treated L. procerum showed higher enzymatic activities of α-amylase (df = 4, t = −45.369, P < 0.001 t-test), amyloglucanase (df = 4, t = −30.845, P < 0.001 t-test) and α-glucosidase (df = 4, t = −285.833, P < 0.001 t-test) (Fig. 6d). Taken together, these outcomes strongly indicated that the bacterial volatile ammonia mediated the conversion of starch to glucose via the activation of starch hydrolyzes-related enzymes.

Deletion of amylolytic enzyme genes causes a growth defect of L. procerum and RTB larvae

Given these findings, we subsequently generated ΔAMYG and ΔAMYA3 mutants of L. procerum by homologous recombination. Carbohydrate composition in the desugared phloem medium (adding 1 g/L, d-glucose and d-pinitol) showed that, when exposed to ammonium, the glucose left in the culture medium colonized by ΔAMYG mutant was significantly reduced compared to wild-type (WT), while deletion of AMYA3 was not (Fig. 7a) (AMYG: df = 7.426, t = 10.572, P < 0.001; AMYA3: df = 14, t = 4.248, P = 0.180 t-test). We found that loss of AMYG led to growth defects of L. procerum (Fig. 7b, c) (b: df = 14, t = 12.648, P < 0.001; c: df = 14, t = 4.075, P = 0.003 t-test), and weight loss of RTB larvae (Fig. 7d) (df = 43, t = 3.681, P = 0.001 t-test). The morphology of ΔAMYG mutant is also different from WT (Supplementary Fig. S7).

(a) Carbohydrate composition in L. procerum-colonized area of desugared phloem medium with additional 1 g/L of d-pinitol and d-glucose at day 5 (left) and GC–MS traces of WT, ΔAMYG, and ΔAMYA3 of L. procerum on desugared phloem medium (right). Fungal growth (b) and dry weight (c) of WT and ΔAMYG of L. procerum on ammonium infused desugared phloem medium at day 13. (d) Effects of exposure of ammonium on the weight change of RTB larvae with the present of WT or ΔAMYG of L. procerum. Error bars of (a–c) represent SEs of eight biological replicates, and error bars of (d) represent SEs of at least 20 biological replicates. Asterisk indicates significant difference between WT, ΔAMYG, and ΔAMYA3 of L. procerum (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NS means no significance.

The inhibition of glucose sensing/metabolism and starch metabolism pathway caused by ΔSUC1 mutant

Having confirmed the conversion of starch to glucose, we then investigated which factors regulate this conversion. A transcription factor deletion of COL-26 and its homology gene has been reported to have a critical role in utilization of starch and integration of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Neurospora crassa and Trichoderma reesei [40]. In this work, the homology gene of COL-26 was identified and named as SUC1 in L. procerum (Supplementary Fig. S8). When compared to WT strains, ΔSUC1 mutants showed growth defects in the presence of ammonium and desugared phloem medium, which also had an extra 1 g/L of d-glucose-13C6 and d-pinitol added (Supplementary Fig. S8a, b). To investigate the functions of SUC1 in this process, we analyzed the carbohydrate composition in the plates and evaluated transcriptional changes in the ΔSUC1 mutant when switched to desugared phloem medium containing 1 g/L of d-glucose-13C6 and d-pinitol under identical conditions as with the WT parent strain (see above). We found that loss of SUC1 has no effect on the content of pinitol and glucose in desugared phloem medium (adding 1 g/L of d-glucose-13C6 and d-pinitol) following fungus consumption in the presence of ammonium (Fig. 8a) (d-pinitol: df = 14, t = 1.87, P = 0.086; d-glucose: df = 14, t = −1.277, P = 0.226 t-test). Furthermore, glucose left in plates with ΔSUC1 mutant was mainly labeled glucose. In contrast, glucose left in plates with WT mainly was natural glucose (Fig. 8b and Supplementary S9) (m/z 319: F2, 21 = 228.376, P < 0.001; m/z 323: F2, 21 = 162.146, P < 0.001 ANOVA, Tukey’s test). Based on the transcription analysis, we found that the main genes in the glucose regulon gene set and starch regulon gene set were downregulated in the ΔSUC1 mutant (Fig. 8c) (PK: df = 4, t = 5.745, P = 0.005; PFK: df = 4, t = 6.450, P = 0.003; PGD: df = 4, t = 4.752, P = 0.009; G6PD: df = 4, t = 3.076, P = 0.037; AMYA3: df = 4, t = 14.602, P < 0.001; AMYG: df = 4, t = 4.983, P = 0.008; α-glu1: df = 4, t = 3.315, P = 0.030; α-glu5: df = 4, t = 0.085, P = 0.936 t-test), including two key genes of the glycolysis (6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase: PGD and glucose 6‐phosphate dehydrogenase: G6PD), two key genes of the pentose phosphate pathway (pyruvate kinase: PK and phosphofructokinase: PFK), and three amylolytic genes (AMYA3, AMYG and α-glu1). In addition, deletion of SUC1 also impaired the growth of L. procerum (Fig. 8d, e) (d: df = 14, t = 10.25, P < 0.001; e: df = 14, t = 5.785, P < 0.001 t-test) and RTB larvae (Fig. 8f) (df = 33.878, t = 3.276, P = 0.002 t-test) significantly. The morphology of ΔSUC1 mutant was different from WT as well (Supplementary Fig. S7). These data indicated that deletion of the SUC1 repressed the glucose sensing/metabolism and starch metabolism pathway in L. procerum with ammonium, which therefore disrupted the beneficial association of L. procerum and RTB larvae.

(a) Carbohydrate composition in L. procerum-colonized area of desugared phloem medium with additional 1 g/L of d-glucose and d-pinitol at day 5. (b) Carbohydrate composition in L. procerum-colonized area of desugared phloem medium with additional 1 g/L of pinitol and 13C6-labeled glucose at day 5. (c) Expression of genes that involved in glucose and starch metabolism in WT and ΔSUC1 of L. procerum on desugared phloem medium at day 5. Fungal growth (d) and dry weight (e) of WT and ΔSUC1 of L. procerum on ammonium infused desugared phloem medium at day 13. (f) Effects of exposure of ammonium on the weight change of RTB larvae with the present of WT or ΔSUC1 of L. procerum. Error bars of a–c represent SEs of eight biological replicates, and error bars of (d) represent SEs of at least 20 biological replicates. Different letters of (b) indicate significant differences among different treatments (P < 0.05). Asterisks of a, c, d, e and f indicate significant difference between WT and ΔSUC1 of L. procerum (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NS means no significance.

Discussion

Many aggressive beetles infesting conifers over a wide geographical range depend upon associations with fungi to fulfill a range of physiological and ecological functions [52,53,54]. Our previous studies have shown that D. valens–L. procerum formed a mutualistic beetle–fungus invasive complex under the nutrient-poor bark, and this mutualism is consistently maintained for multiple generations [55]. However, competition for nutritional resources is ultimately unavoidable. The symbiotic bacteria volatile ammonia regulates carbohydrate consumption in L. procerum to eliminate the negative effects on the RTB larval growth caused by the carbohydrate competition of L. procerum, yet little was known prior to this study about the mechanism behind this phenomenon. Based on our results, we propose that D. valens maintains mutualistic associations with the beneficial symbiont L. procerum under poor nutrition with the symbiotic bacterial volatile regulating the mutualistic fungus’ carbohydrate metabolism. On one hand, the carbohydrate consumption of L. procerum is accelerated (Fig. 4), which is beneficial for its competition with antagonistic fungi while the carbohydrate consumption of antagonistic fungi was significantly reduced by symbiotic bacteria [17]. Moreover, it induces the L. procerum starch metabolism pathway to secret extracellular amylase (Fig. 6), converting the abundant starch in the phloem into a high nutritional-value carbon source (glucose) (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S5), and providing sufficient preferred carbon source for the symbionts, maintaining the stability of the D. valens–L. procerum mutualism [47]. As glucose is a better carbon source for these associated bacteria, the conversion not only replenishes the energy cost of releasing ammonia but also provides more energy for its growth [47]. These results show carbohydrate metabolism mediated by associated bacteria–fungi interactions can have a key role in maintaining the bark beetle–fungus mutualism in face of nutritional limitation. In addition, we find that the transcription factor, SUC1, is an essential regulator for the process (Fig. 8). Our RNA-sequence data also showed that ammonia nitrogen is converted into glutamate by glutamate dehydrogenase (Supplementary Fig. S10), and further investigation is needed to explore the full extent of how ammonia is used as a nitrogen source [37]. Notably, the homolog of SUC1 in N. crassa, COL-26, was reported to have a role in coordinating the utilization of starch components with nitrogen regulation [40].

In nature, ten fungal species were found in association with RTB, while only L. procerum was consistently found with D. valens at all collection sites and the isolation frequency of this species was the highest in China [42, 43]. Due to the consistent relationship and potential to facilitate the invasion of RTB, L. procerum has been proven to be a symbiotic fungus for RTB [17]. In pine phloem, carbon sources available for both fungal and bacterial symbionts are mainly d-pinitol followed by d-glucose [31]. Previous studies have shown that dominant bacteria associated with RTB and their released volatiles, including ammonia, inhibit the growth and main carbohydrates consumption of antagonistic fungi O. minus, which alleviate antagonistic effects of O. minus on RTB larvae [37, 47, 56]. On the contrary, in this study, the volatile ammonia from bacteria associated with RTB accelerates the consumption of the main carbohydrates by mutualistic fungi L. procerum. The growth of L. procerum is significantly enhanced by the acceleration of carbohydrate consumption. This enhancement might have resulted in higher pathogenicity to Chinese host pines since L. procerum is generally considered as a weakly pathogenic fungus, thereby facilitating the invasion of RTB by helping to overcome tree defenses [17]. Taken together, all of these results indicated that accelerated consumption of carbohydrates by the mutualistic fungi L. procerum improves the chances of this mutualistic fungal symbiont to outcompete other microbial competitors and leads L. procerum to be the dominant fungus in the gallery with different life stages of RTB [42]. The enhancement of growth and competitiveness of L. procerum is potentially conducive to the successful invasion of RTB.

The mutualistic fungi L. procerum has been revealed to be beneficial to the colonization and invasion of the RTB [17]. However, the competition for carbon source via carbohydrate competition could drastically inhibit RTB larval growth and then indirectly affect bark beetle population dynamics [31]. The accelerated consumption of glucose by fungi L. procerum would inevitably affect the maintenance of the D. valens–L. procerum mutualism. However, RTB successfully maintains beneficial fungi under natural conditions in the field, which suggests that the mutualism has a strategy to overcome the disadvantages of nutritional competition. Our current study demonstrates that the associated bacteria can alleviate the antagonistic effects of the fungus L. procerum on RTB larval growth with the volatile ammonia regulating carbon source usage in the fungus. Tripartite beetle–fungus–bacterium mutualisms are widespread in nature, e.g., Dendroctonus frontalis uses associated bacteria to protect its fungal food source from a competitor fungus to maintain the D. frontalis–Entomocorticium sp. mutualism [2]. In our study, we found that the bacterial volatile ammonia, as a nitrogen source, triggered L. procerum to convert the phloem’s abundant starch resources, normally not easily accessible to RTB, into glucose by the activation of starch metabolism pathways, while elimination of the conversion by AMYG deletion impaired the growth of L. procerum and RTB larvae. Thus, we suggest that the conversion of starch into glucose compensates the acceleration of carbohydrate consumption, and subsequently alleviates the nutrient competition between beneficial fungi and bark beetles.

The preceding results showed that the volatile ammonia not only accelerated the consumption of glucose but also triggered conversion of starch into glucose in L. procerum. The acceleration of carbohydrate consumption and the conversion of starch into glucose benefit this invasive beetle–fungus complex by alleviating nutrition-limitation in the presence of RTB-associated bacteria. However, the molecular mechanism of how the volatile ammonia influences the metabolic ability of L. procerum remains unknown. In N. crassa, the transcription factor COL-26 was reported to have a role in coordinating the utilization of starch components with nitrogen regulation [40]. Here, we found a homolog of COL-26 in L. procerum, SUC1. The ΔSUC1 mutant showed a defect on converting starch to glucose and inhibited the utilization of glucose. All of these results demonstrated that the volatile ammonia influenced the metabolism of L. procerum by regulating the expression of SUC1, which functions as a mediator of glucose signaling and metabolism.

Overall, we defined a novel nutrient consumption–compensation strategy to illustrate how insects can maintain mutualistic associations with beneficial symbionts under nutritional stress. Our results revealed that the nutrient consumption–compensation strategy, mediated by tripartite beetle–fungus–bacterium interactions, benefits the invasive bark beetle by facilitating the maintenance of its mutualistic associations with beneficial fungus under poor nutritional conditions. As nutritional competition is inevitable in the case of a nutrient-poor environment, this nutrient consumption–compensation strategy may prove to be ubiquitous among many species of bark beetles and their symbiotic fungi [9]. Furthermore, several investigations have revealed that the phloem of bark is nitrogen-limited and bark beetle-associated microbes could help ease nitrogen limitation [9, 22, 57]. In this work, we found that bacterial ammonia serves as a nitrogen source to regulate the stability of the bark beetle–fungus complex, suggesting that nitrogen fertilizers used in farming might affect the stability of other insect–microbe symbionts in plantation forests or agriculture. Understanding the consumption–compensation strategy not only provides novel insights into the maintenance of insect–microbes mutualisms, but also may lead to the exploration of new management strategies for these devastating forest pests.

References

Currie CR, Scott JA, Summerbell RC, Malloch D. Fungus-growing ants use antibiotic-producing bacteria to control garden parasites. Nature. 1999;398:701.

Scott JJ, Oh DC, Yuceer MC, Klepzig KD, Clardy J, Currie CR. Bacterial protection of beetle-fungus mutualism. Science. 2008;322:63.

Moran NA, Ochman H, Hammer TJ. Evolutionary and ecological consequences of gut microbial communities. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2019;50:451–75.

Strand MR. Composition and functional roles of the gut microbiota in mosquitoes. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2018;28:59–65.

HDFL Henrik, Schiøtt M, Rogowska-Wrzesinska A, Nygaard S, Roepstorff P, Boomsma JJ. Laccase detoxification mediates the nutritional alliance between leaf-cutting ants and fungus-garden symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:583–7.

Franklin O, Näsholm T, Högberg P, Högberg MN. Forests trapped in nitrogen limitation–an ecological market perspective on ectomycorrhizal symbiosis. N Phytol. 2014;203:657–66.

Herre EA, West SA. Conflict of interest in a mutualism: documenting the elusive fig wasp-seed trade-off. Proc R Soc B: Biol Sci. 1997;264:1501–7.

Herre EA, Knowlton N, Mueller UG, Rehner SA. The evolution of mutualisms: exploring the paths between conflict and cooperation. Trends Ecol Evol. 1999;14:49–53.

Ayres MP, Wilkens RT, Ruel JJ, Lombardero MJ, Vallery E. Nitrogen budgets of phloem‐feeding bark beetles with and without symbiotic fungi. Ecology. 2000;81:2198–210.

Klepzig KD, Moser JC, Lombardero MJ, Ayres MP, Hofstetter RW, Walkinshaw CJ. Mutualism and antagonism: ecological interactions among bark beetles, mites and fungi. In:Jeger MJ, Spence NJ, editors. Biotic interactions in plant-pathogen associations. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing; 2001. p. 237–67.

Wood DL. The role of pheromones, kairomones, and allomones in the host selection and colonization behavior of bark beetles. Annu Rev Entomol. 1982;27:411–46.

Six DL. Bark beetle-fungus symbioses. In: Bourtzis K, Miller TA, editors. Insect symbiosis. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2003. p. 97–114.

Sauvard D. General biology of bark beetles. In: Lieutier F, Day KR, Battisti A, Gregoire JC, Evans HF, editors. Bark and wood boring insects in living trees in Europe: a synthesis. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; 2004. p. 63–88.

Harrington TC. Ecology and evolution of mycophagous bark beetles and their fungal partners. In: Vega FE, Blackwell M, editors. Ecological and evolutionary advances in insect-fungal associations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 257–91.

Whitney HS, Bandoni RJ, Oberwinkler F. Entomocorticium dendroctoni gen. et sp. nov. (Basidiomycotina), a possible nutritional symbiote of the mountain pine beetle in lodgepole pine in British Columbia. Can J Bot. 1987;65:95–102.

Six DL. Ecological and evolutionary determinants of bark beetle-fungus symbioses. Insects. 2012;3:339–66.

Lu M, Wingfield MJ, Gillette NE, Mori SR, Sun JH. Complex interactions among host pines and fungi vectored by an invasive bark beetle. N Phytol. 2010;187:859–66.

Six DL, Paine TD. Effects of mycangial fungi and host tree species on progeny survival and emergence of Dendroctonus ponderosae (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). Environ Entomol. 1998;27:1393–401.

Mueller UG, Gerardo NM, Aanen DK, Six DL, Schultz TR. The evolution of agriculture in insects. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2005;36:563–95.

Bleiker KP, Six DL. Dietary benefits of fungal associates to an eruptive herbivore: potential implications of multiple associates on host population dynamics. Environ Entomol. 2014;36:1384–96.

Scriber JM, Slansky F Jr. The nutritional ecology of immature insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 1981;26:183–211.

Six DL, Wingfield MJ. The role of phytopathogenicity in bark beetle–fungus symbioses: a challenge to the classic paradigm. Annu Rev Entomol. 2011;56:255–72.

Douglas AE, Minto LB, Wilkinson TL. Quantifying nutrient production by the microbial symbionts in an aphid. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:349–58.

Zheng H, Powell JE, Steele MI, Dietrich C, Moran NA. Honeybee gut microbiota promotes host weight gain via bacterial metabolism and hormonal signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:4775–80.

Valzania L, Coon KL, Vogel KJ, Brown MR, Strand MR. Hypoxia-induced transcription factor signaling is essential for larval growth of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:457–65.

Shukla SP, Plata C, Reichelt M, Steiger S, Heckel DG, Kaltenpoth M, et al. Microbiome-assisted carrion preservation aids larval development in a burying beetle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:11274–9.

Chong RA, Moran NA. Evolutionary loss and replacement of Buchnera, the obligate endosymbiont of aphids. ISME J. 2018;12:898–908.

Sabree ZL, Kambhampati S, Moran NA. Nitrogen recycling and nutritional provisioning by Blattabacterium, the cockroach endosymbiont. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19521–6.

Beaver RA, Wilding N, Collins N, Hammond P, Webber J. Insect-fungus relationship in the bark and ambrosia beetles. In: Wilding N, Collins NM, Hammond PM, Webber JF, editors. Insect–fungus interactions. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1989. p. 121–43.

Nasir H, Noda H. Yeast-like symbiotes as a sterol source in anobiid beetles (Coleoptera, Anobiidae): possible metabolic pathways from fungal sterols to 7‐dehydrocholesterol. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2003;52:175–82.

Wang B, Lu M, Cheng CH, Salcedo C, Sun JH. Saccharide-mediated antagonistic effects of bark beetle fungal associates on larvae. Biol Lett. 2013;9:20120787.

Wang B, Salcedo C, Lu M, Sun JH. Mutual interactions between an invasive bark beetle and its associated fungi. Bull Entomol Res. 2012;102:71–7.

House HL. Insect nutrition. Annu Rev Entomol. 1961;6:13–26.

Cardoza YJ, Klepzig KD, Raffa KF. Bacteria in oral secretions of an endophytic insect inhibit antagonistic fungi. Ecol Entomol. 2006;31:636–45.

Adams AS, Six DL, Adams SM, Holben WE. In vitro interactions between yeasts and bacteria and the fungal symbionts of the mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae). Micro Ecol. 2008;56:460–6.

Adams AS, Currie CR, Cardoza Y, Klepzig KD, Raffa KF. Effects of symbiotic bacteria and tree chemistry on the growth and reproduction of bark beetle fungal symbionts. Can J For Res. 2009;39:1133–47.

Zhou FY, Xu LT, Wang SS, Wang B, Lou QZ, Lu M, et al. Bacterial volatile ammonia regulates the consumption sequence of D-pinitol and D-glucose in a fungus associated with an invasive bark beetle. ISME J. 2017;11:2809–20.

Wilson RA, Jenkinson JM, Gibson RP, Littlechild JA, Wang ZY, Talbot NJ. Tps1 regulates the pentose phosphate pathway, nitrogen metabolism and fungal virulence. EMBO J. 2007;26:3673–85.

Fernandez J, Wright JD, Hartline D, Quispe CF, Madayiputhiya N, Wilson RA. Principles of carbon catabolite repression in the rice blast fungus: Tps1, Nmr1-3, and a MATE–Family Pump regulate glucose metabolism during infection. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002673.

Xiong Y, Wu VW, Lubbe A, Qin LN, Deng SW, Kennedy M, et al. A fungal transcription factor essential for starch degradation affects integration of carbon and nitrogen metabolism. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006737.

Sun JH, Lu M, Gillette NE, Wingfield MJ. Red turpentine beetle: innocuous native becomes invasive tree killer in China. Annu Rev Entomol. 2013;58:293–311.

Lu M, Zhou XD, De Beer ZW, Wingfield MJ, Sun JH. Ophiostomatoid fungi associated with the invasive pine-infesting bark beetle, Dendroctonus valens, in China. Fungal Divers. 2009;38:133–45.

Taerum SJ, Duong TA, De Beer ZW, Gillette N, Sun JH, Owen DR, et al. Large shift in symbiont assemblage in the invasive red turpentine beetle. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78126.

Cheng CH, Zhou FY, Lu M, Sun JH. Inducible pine rosin defense mediates interactions between an invasive insect-fungal complex and newly acquired sympatric fungal associates. Integr Zool. 2015;10:453–64.

Ulyshen MD. Insect-mediated nitrogen dynamics in decomposing wood. Ecol Entomol. 2015;40:97–112.

Morales-Jiménez J, Vera-Ponce De León A, García-Domínguez A, Martínez-Romero E, Zúñiga G, Hernández-Rodríguez C. Nitrogen-fixing and uricolytic bacteria associated with the gut of Dendroctonus rhizophagus and Dendroctonus valens (Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Micro Ecol. 2013;66:200–10.

Zhou FY, Lou QZ, Wang B, Xu LT, Cheng CC, Lu M, et al. Altered carbohydrates allocation by associated bacteria-fungi interactions in a bark beetle-microbe symbiosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20135.

Feng P, Shang YF, Cen K, Wang CS. Fungal biosynthesis of the bibenzoquinone oosporein to evade insect immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:11365–70.

Kim JS, Kwon CS, Son KH. Inhibition of alpha-glucosidase and amylase by luteolin, a flavonoid. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000;64:2458–61.

Mullins ED, Kang S. Transformation: a tool for studying fungal pathogens of plants. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:2043–52.

Xu C, Zhang X, Qian Y, Chen X, Liu R, Zeng G, et al. A high-throughput gene disruption methodology for the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e107657.

Cai YW, Cheng XY, Xu RM, Duan DH, Kirkendall LR. Genetic diversity and biogeography of red turpentine beetle Dendroctonus valensin its native and invasive regions. Insect Sci. 2008;15:291–301.

Paine TD, Raffa KF, Harrington TC. Interactions among scolytid bark beetles, their associated fungi, and live host conifers. Annu Rev Entomol. 1997;42:179–206.

Viiri H, Lieutier F. Ophiostomatoid fungi associated with the spruce bark beetle, Ips typographus, in three areas in France. Ann Sci. 2004;61:215–9.

Cheng CH, Xu LT, Xu DD, Lou QZ, Lu M, Sun JH. Does cryptic microbiota mitigate pine resistance to an invasive beetle-fungus complex? Implications for invasion potential. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33110.

Wang SS, Zhou FY, Wang B, Xu DD, Lu M, Sun JH. Volatiles produced by bacteria alleviate antagonistic effects of one associated fungus on Dendroctonus valens larvae. Sci China Life Sci. 2017;60:924–6.

Ayayee P, Rosa C, Ferry JG, Felton G, Saunders M, Hoover K. Gut microbes contribute to nitrogen provisioning in a wood-feeding cerambycid. Environ Entomol. 2014;43:903–12.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Frontier Science Key Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (QYZDJ-SSW-SMC024) and National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0600100 and 2018YFC1200400). We appreciate the constructive comments from two anonymous reviewers, which greatly improved the quality of our paper. We are grateful to Dr. Cheng-Shu Wang, Yun-Dan Wang, and Xi-Wen Tong for their help in experimental methods, and Dr. Xing-Zhong Liu and Ya-Ni Fan for providing us the disruption plasmid. We thank Mr. Ji-Meng Kou (Northeast Forestry University, China) for his assistance in sample collection. Thanks also extended to Dr. Zhi-Wei Kang (Northwest A&F University, China) for statistical assistance and comments on the manuscript and Dr. Nancy E. Gillette for her review of an earlier version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FL and JS designed the study; FL performed the experiments; and FL, JDW, QC, ML, and JS wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, F., Wickham, J.D., Cao, Q. et al. An invasive beetle–fungus complex is maintained by fungal nutritional-compensation mediated by bacterial volatiles. ISME J 14, 2829–2842 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00740-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00740-w

This article is cited by

-

A review on nutritional and non-nutritional interactions of symbiotic and associated fungi with insect

Symbiosis (2023)

-

Mutualism promotes insect fitness by fungal nutrient compensation and facilitates fungus propagation by mediating insect oviposition preference

The ISME Journal (2022)

-

Phylogeny of Leptographium qinlingensis cytochrome P450 genes and transcription levels of six CYPs in response to different nutrition media or terpenoids

Archives of Microbiology (2022)