Abstract

Pseudomonas protegens are multi-talented plant-colonizing bacteria that suppress plant pathogens and stimulate plant defenses. In addition, they are capable of invading and killing agriculturally important plant pest insects that makes them promising candidates for biocontrol applications. Here we assessed the role of type VI secretion system (T6SS) components of type strain CHA0 during interaction with larvae of the cabbage pest Pieris brassicae. We show that the T6SS core apparatus and two VgrG modules, encompassing the respective T6SS spikes (VgrG1a and VgrG1b) and associated effectors (RhsA and Ghh1), contribute significantly to insect pathogenicity of P. protegens in oral infection assays but not when bacteria are injected directly into the hemolymph. Monitoring of the colonization levels of P. protegens in the gut, hemolymph, and excrements of the insect larvae revealed that the invader relies on T6SS and VgrG1a module function to promote hemocoel invasion. A 16S metagenomic analysis demonstrated that T6SS-supported invasion by P. protegens induces significant changes in the insect gut microbiome affecting notably Enterobacteriaceae, a dominant group of the commensal gut bacteria. Our study supports the concept that pathogens deploy T6SS-based strategies to disrupt the commensal microbiota in order to promote host colonization and pathogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacteria of the Pseudomonas fluorescens species complex [1] are commonly associated with plant and soil environments and many exert plant-beneficial functions, including the suppression of plant diseases and stimulation of plant defenses [2, 3]. Moreover, a subgroup encompassing the species Pseudomonas protegens and Pseudomonas chlororaphis is capable of engaging in pathogenic interactions with plant pest insects [4, 5]. The insect-pathogenic and plant-beneficial activities and the capacity to colonize the two contrasting hosts makes these bacteria promising candidates for biocontrol applications in agriculture.

P. protegens type strain CHA0 investigated here is among the best-characterized environmental bacteria with plant-protecting activities [4,5,6,7]. CHA0 exhibits potent oral insecticidal activity toward herbivorous larvae of several major Lepidopteran pest insects of agricultural crops [4, 5, 8, 9]. A number of virulence factors contributing to insect pathogenicity have been identified in P. protegens CHA0 and the closely related strain Pf-5 [10]. They include several toxins (Fit toxin, hydrogen cyanide, cyclic lipopeptides, rhizoxins) and secreted lytic enzymes (chitinase, phospholipase) [5, 8, 11,12,13,14]. The infection process starts with the ingestion of P. protegens by the larvae feeding on contaminated plant tissues, leading to the establishment of the invader in the intestinal tract [4]. The bacteria then cross the gut epithelial barrier to invade the hemocoel by a yet unknown mechanism. This passage can take place as early as 24 h after oral infection [4, 5, 8]. Owing to a particular O-antigen decoration of the cell surface, P. protegens is capable of resisting antimicrobial peptides (cecropins), i.e., central defense molecules of the insect [15]. In the hemolymph, P. protegens proliferates and produces specific virulence factors, notably the insecticidal toxin Fit, resulting in septicemia and ultimately death of the insect [8, 13, 16].

During the establishment in the insect gut and the preparation of the passage through the gut epithelial barrier, invading P. protegens cells face competition from the resident gut microbiota. Nothing is currently known about the factors that help the bacteria to be competitive during this crucial infection step. We speculated that type VI secretion system (T6SS)-mediated antagonism toward commensal gut bacteria might be involved. The T6SS is as a sophisticated nano-weapon used by many Gram-negative bacteria to inject toxic effector proteins into prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells, thereby promoting interbacterial antagonism and virulence in various host environments such as the gut [17,18,19,20,21]. T6SS-mediated strategies are known to help pathogenic bacteria achieve optimal host colonization by displacing host commensal bacteria or eliminating bacterial competitors [19]. This is exemplified by the enteropathogens Vibrio cholerae and Salmonella Typhimurium, which were shown to deploy T6SS-based antibacterial activities for the colonization of animal models [22, 23]. Likewise, T6SS-mediated interbacterial competition promotes host plant colonization by phytopathogenic bacteria [24, 25].

The T6SS apparatus shows striking similarity with the injection machinery of bacteriophages [26, 27] and consists of a membrane-anchoring complex that stands on a baseplate-like structure to which is docked a tube that is composed of Hcp proteins [17, 18, 20, 21]. The Hcp tube is fitted in a contractile sheath-like structure and capped with a spike formed by VgrG proteins [17, 18]. PAAR domain proteins sharpen the VgrG spike and can function as adapters for effector delivery [18, 28,29,30]. Antibacterial effectors typically have severe lytic and toxic activity targeting essential bacterial structures, such as cell walls, cell membranes, and nucleic acids [31,32,33]. Some effectors impact eukaryotic cells by manipulating the cytoskeleton or exerting cytotoxic effects [19]. Cognate immunity proteins protect the producer bacteria from self-destruction [28, 32]. The T6SS can be fitted with different VgrG–PAAR–effector assemblies allowing a modular usage of the injection device to deliver diverse toxic effectors [28,29,30, 34].

Here we report on the characterization of the T6SS core apparatus and two VgrG modules with associated effectors of P. protegens CHA0 for their role in insect invasion and pathogenesis. Using larvae of the cabbage butterfly Pieris brassicae as plant-feeding insect model, we establish that the T6SS and both VgrG modules contribute to insect killing following oral infection. We show that P. protegens uses the T6SS and one of the VgrG modules to promote insect gut colonization and competition with commensal gut bacteria. A 16S metagenomic analysis demonstrates that TSS6-supported invasion by P. protegens induces significant changes in the insect gut microbiome affecting notably Enterobacteriaceae, a dominant group of the commensal gut bacteria.

Material and methods

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and in vitro competition assays

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables S1-S2. Bacterial culture conditions, isolation, and identification of commensal insect gut bacteria and interbacterial competition assays are detailed in Supplementary Information.

T6SS core apparatus and VgrG module loci in the P. protegens CHA0 genome

Gene clusters encoding the T6SS core apparatus and the VgrG1a and VgrG1b modules were localized in the chromosome of P. protegens CHA0 by performing BLAST searches on the NCBI website (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BlastAlign.cgi) and in the Pseudomonas Genome Database [35] focusing on orthologous genes and shared synteny in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. For the identification of the T6SS and the VgrG proteins, we used blastp with a minimum of 70% of amino acid sequence identity over at least 70% of the total sequence length. We admitted less sequence conservation for the detection of the effectors associated with the VgrG modules. The functions of the identified proteins were predicted using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database Search [36] and InterPro [37] with default parameters and published information about the related proteins in P. aeruginosa [34, 38,39,40].

Creation of deletion mutants of P. protegens CHA0

Mutants of strain CHA0 with deletions of gene clusters encoding (i) the T6SS core apparatus (PFLCHA0_RS30085 through PFLCHA0_RS30180), (ii) the VgrG1a module encompassing predicted spike VgrG1a, effector RhsA and immunity protein RhsI (PFLCHA0_RS30185 through PFLCHA0_RS30220), and (iii) the VgrG1b module encompassing predicted spike VgrG1b, effector Ghh1, and immunity protein GhhI (PFLCHA0_RS15145 through PFLCHA0_RS15190) were constructed. In addition, mutants with individual deletions of the effector genes rhsA (PFLCHA0_RS30195) and ghh1 (PFLCHA0_RS31250) and VgrG spike genes vgrG1a (PFLCHA0_RS30185) and vgrG1b (PFLCHA0_RS15170) were generated. Mutants (Table S1) were created using the suicide vector pEMG and the I-SceI system [41] adapted to P. protegens [16], with plasmids and primers listed in Tables S2-S3.

P. brassicae pathogenicity assays

The insect pathogenicity of P. protegens strains was assessed in oral infection and injection assays with larvae of P. brassicae. After hatching, larvae were kept on pesticide-free cabbage plants in a Percival PGC-7L2 plant growth chamber at 25 °C and 60% relative humidity, with 16 h of light and 8 h of darkness. For the oral infection assay, 18 second instar larvae (body length 1.0–1.5 cm) were selected for each testing condition. Larvae were starved the night before infection and placed individually into six-well culture plates. Each larva was fed with a 0.6-g pellet of artificial diet containing horseradish powder as feeding attractant (adapted from ref. [42]). Diet pellets were inoculated with 5 μl of a suspension containing 5.0 × 106 washed bacterial cells in sterile 0.9% NaCl solution. Artificial diet with the same volume of NaCl solution was used as negative control. Larvae that did not consume the entire inoculated diet pellet were excluded from the experiment. After 24 h, larvae from each culture plate were transferred to a Petri dish, fed with fresh sterile artificial diet, and monitored for survival every 24 h for 7 days.

For the injection assay, bacterial suspensions (2.5 µl containing 102 washed cells) were injected via the second proleg directly into the hemolymph of fourth instar P. brassicae larvae (body length 2.5–3.0 cm). In each experiment, 18 larvae per treatment were injected and incubated in groups of three in Petri dishes in the plant growth chamber. Larval survival was checked hourly starting at 19 h postinjection.

P. brassicae colonization assays

For use in the colonization assay with P. brassicae larvae, bacterial strains were marked with a constitutively expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tag using pBK-miniTn7-gfp1 [8]. Oral infection was done as described above, except that third instar larvae (body length 2.0–2.5 cm) and a larger bacterial inoculum (i.e., 10 μl with 1.0 × 107 cells per larva) were used. At 24 h following oral infection, each larva was placed on ice, bled by cutting a proleg to collect the hemolymph, and then dissected to extract the entire gut. In addition, excrements were instantly collected from corresponding culture plate wells. Hemolymph, gut, and excrement samples were placed in tubes containing 900 μl of sterile 0.9% NaCl solution and homogenized. Aliquots of 10 μl of serially diluted samples were spotted on NA containing 10 µg ml−1 of gentamycin. Colony-forming unit counts were determined with a Fusion FX Spectra imaging platform (Vilber-Lourmat®) by checking colonies for fluorescence under blue light (~470 nm) indicative of growth of GFP-tagged strains.

16S rRNA gene sequencing for metagenomic analysis

Third-instar Pieris larvae were orally infected with P. protegens strains as described above for the colonization assays. For each condition, 40 larvae were infected. At 24 h following oral infection, each larva was surface-disinfested in ethanol and dissected to extract the gut. For each condition, 10 samples each containing pooled guts from four larvae were prepared. Samples were processed by Geno-Screen (Lille, France) for DNA extraction, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and metagenome analysis using the Metabiote® pipeline (see Supplementary Information). Following establishment of the abundance matrix, non-infected insect gut samples in which no Pseudomonas operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were detected were removed from the analysis (Table S4). Sequences affiliated to mitochondria and chloroplasts (indicative of insect tissues and ingested plant material) were removed from the sample prior to analysis. The abundance matrix was loaded into the Calypso software version 8.18 [43] using total sum scaling and cumulative sum scaling normalization [44]. Statistical analysis for 16S metagenomic data (principal coordinates analyses (PCAs), calculation of diversity indices, and comparison of taxa abundances between treatments) were done using the Calypso software.

Statistical analysis of data

Data were statistically analyzed using R studio version 3.3.2 (http://www.rstudio.com/) and considered significantly different when P < 0.05. For oral pathogenicity assays with P. brassicae, only sample sets with <2 dead larvae out of 18 in the non-infected control were considered for statistical analysis. Data were analyzed using the mixed-effect Cox model. To identify significant differences between treatments, analysis of variance (ANOVA) coupled with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test including Bonferroni correction was employed. For insect colonization and interbacterial competition assays, data were log10-transformed. Student’s t test was performed to detect significant differences between colonization levels of the CHA0 wild type and ∆T6SS mutant. ANOVA followed by Fisher’s least significant difference test was done to detect significant differences between colonization levels of the CHA0 wild type and ∆VgrG1a-mod and ∆VgrG1b-mod mutants. Data of interbacterial competition assays were analyzed using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test.

Results and discussion

Characterization of gene clusters encoding the T6SS and VgrG modules in P. protegens CHA0

To identify T6SS components in P. protegens CHA0, we searched for protein homology with the well-annotated T6SS components of P. aeruginosa PAO1. The cluster encoding the unique T6SS core apparatus of CHA0 ranges from taqQ (PFLCHA0_RS30085) to clpV (PFLCHA0_RS30180) and shows extensive similarity to the H1-T6SS cluster of P. aeruginosa PAO1 [39, 45, 46] in terms of sequence identities and synteny (Fig. 1; Table S5). A near identical T6SS gene cluster exists also in the related strain P. protegens Pf-5 [47, 48]. Within the H1-T6SS locus of CHA0, the tag encoded proteins (PFLCHA0_RS30085 through PFLCHA0_RS30115) share at least 55% identity with the PAO1 PpkA-PppA and Tag proteins (Fig. 1; Table S5) that are involved in T6SS signaling and regulation [18, 20, 49]. The 13 conserved tss genes upstream of the tag genes are required for the assembly of the T6SS core components, including baseplate, membrane complex, sheath, and tube [17, 21, 29, 50, 51].

T6SS and VgrG1a and VgrG1b module gene clusters of Pseudomonas protegens CHA0 and orthologous genomic regions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Sequence identities and predicted functions are detailed in Supplementary Table S5. PAO1 genes that are absent in the CHA0 genome are shown as empty arrows. Numbers indicate the locus tags for P. protegens CHA0 (prefix PFLCHA0_RS…) and P. aeruginosa PAO1 (prefix PA…)

T6SS-associated membrane-puncturing devices are mainly composed by VgrG proteins forming a spike that is sharpened by associated PAAR proteins [29, 30]. We identified two proteins in CHA0 that share >70% identity with the spike proteins VgrG1a (PA0091) and VgrG1b (PA0095) of P. aeruginosa PAO1 [34, 38] and to which we attributed the same names (Fig. 1; Table S5). Both predicted CHA0 spike proteins harbor a conserved VI_Rhs_Vgr domain (TIGR03361), which identifies them as typical members of the T6SS Vgr protein family [46]. The CHA0 vgrG1a gene (PFLCHA0_RS30185) is located adjacent to the T6SS core apparatus genes, whereas CHA0 vgrG1b (PFLCHA0_RS15170) is located distant from the T6SS locus (Fig. 1), however, in notable vicinity of the locus encoding the insecticidal toxin Fit [52].

The vgrG genes are often located in clusters with genes encoding toxic T6SS effectors along with adaptor and cognate immunity proteins [29]. We found that vgrG1a and vgrG1b of CHA0 are part of such clusters that we termed here VgrG modules. The predicted VgrG1a module ranges from locus tags PFLCHA0_RS30185 to PFLCHA0_RS30220 (Fig. 1; Table S5). Within this module, PFLCHA0_RS30195, encodes a putative effector of the rearrangement hotspot (Rhs) protein family [53], which shares 29% identity over 74% of the entire protein length with the Rhs protein Tse5/RhsP1 (PA2684) of P. aeruginosa [33, 34]. A near-identical Rhs effector (99% identity with PFLCHA0_RS30195) belonging to the DNase enzyme family and termed RhsA (PFL_6096) was recently functionally characterized in P. protegens Pf-5 along with its cognate immunity protein RhsI (PFL_6097; 99% identity with PFLCHA0_RS30200) [54]. We adopted the same terminology for CHA0. The central part of RhsA of CHA0 harbors numerous Rhs repeats, which are thought to encapsulate the C-terminal toxic domain of T6SS-delivered Rhs-type effectors [28]. Like other Rhs T6SS effectors, RhsA of CHA0 possesses a typical N-terminal PAAR domain, described to bind and sharpen the VgrG spike to facilitate effector translocation into the targeted cell [18, 30, 53]. Moreover, two loci flanking the rhsA–rhsI effector–immunity gene pair of CHA0 (PFLCHA0_RS30190, PFLCHA0_RS30210) encode proteins of the DUF1795 superfamily, recently identified as adaptor proteins required for the secretion of PAAR domain T6SS effectors [18, 30, 54].

The predicted VgrG1b module of CHA0 comprises PFLCHA0_RS15145 through PFLCHA0_RS15170. Predicted proteins share 35–74% identity with those encoded by the P. aeruginosa PAO1 vgrG1b locus (PA0095 through PA0101) [34] located near the H1-T6SS locus (Fig. 1; Table S5). Within the CHA0 VgrG1b module, PFLCHA0_RS31250 is predicted to encode a T6SS effector that we named Ghh1. It harbors an N-terminal PAAR-like domain and a C-terminal TOX-GHH2 domain with predicted nuclease activity like the orthologous PA0099-encoded effector Tse7 (48% identity) in P. aeruginosa [34, 40]. By analogy, we predict that the gene that follows ghh1 in CHA0 (PFLCHA0_RS15150) encodes the cognate immunity protein and termed it ghhI. PFLCHA0_RS15160, upstream of ghh1, encodes a protein of the DUF2169 superfamily, members of which have recently been suggested to serve as adaptors or chaperones aiding binding of PAAR domain T6SS effectors to the VgrG spike [55, 56].

To summarize, our analysis of the genome of P. protegens CHA0 identified gene clusters coding for a single T6SS core apparatus and two distinct VgrG modules that we termed VgrG1a module (with spike VgrG1a and effector RhsA) and VgrG1b module (with spike VgrG1b and effector Ghh1). To assess the involvement of these components in insect pathogenicity, insect colonization, and competition with the gut microbiome, we compared the activity of wild-type CHA0 with mutants in which we deleted the entire T6SS or VgrG module gene clusters (ΔT6SS, ΔVgrG1a-mod or ΔVgrG1b-mod, respectively) or individual genes encoding the respective VgrG spikes or effectors (ΔvgrG1a, ΔvgrG1b, ΔrhsA, or Δghh1, respectively) (Table S1).

The T6SS contributes to insect pathogenicity of P. protegens following oral infection

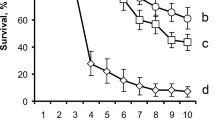

To assess the relative contribution of the T6SS and the two VgrG modules to the insect pathogenicity of P. protegens, we orally infected larvae of the plant pest insect P. brassicae with the CHA0 wild type and the various T6SS-related mutants and monitored larval survival for 1 week. After this period, <12% of the larvae infected by the CHA0 wild type had survived, whereas almost 90% of the larvae of the control treatment without bacteria administration were alive and healthy (Fig. 2a). Larval mortality was significantly lower when they were fed the ΔT6SS, ΔVgrG1a-mod, or ΔVgrG1b-mod mutants. More than 25% of these larvae survived, highlighting that the T6SS and the two VgrG modules are involved in the infection process. This was further supported by our finding that CHA0 mutants with individual deletions of the respective Vgr spike (ΔvgrG1a, ΔvgrG1b) or effector genes (ΔrhsA, Δghh1) were equally impaired in oral pathogenicity toward the Pieris larvae (Fig. S1).

The T6SS and the VgrG modules contribute to insect pathogenicity of Pseudomonas protegens CHA0 upon oral infection but not upon injection. a Oral activity was tested by feeding larvae of Pieris brassicae artificial diet inoculated with 5 × 106 cells of wild-type CHA0 or its ΔT6SS, ΔVgrG1a-mod or ΔVgrG1b-mod mutants and monitoring their survival daily during 1 week. b Systemic activity was tested by injecting 102 cells of the bacterial strains directly into the hemolymph of the larvae and checking their survival hourly, starting at 19 h postinjection. The feeding and injection experiments were repeated six and five times, respectively, with 18 larvae per treatment in each individual experiment. Sterile NaCl solution at 0.9% served as negative control. Data were analyzed using the mixed-effect Cox model incorporating the experiment repetition factor and one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s test with Bonferroni correction. For each panel, treatments with different letters (a–c) significantly differed from each other (P < 0.05)

Our previous studies established hemocoel invasion as a crucial step in insect pathogenesis of P. protegens CHA0 [4, 13]. The bacterium uses a tight control system to specifically activate the production of the insecticidal toxin Fit in this compartment leading to an acute disease phase and the death of the insect [8, 16]. Other toxic metabolites, notably hydrogen cyanide and the cyclic lipopeptide orfamide, contribute to insect killing during this infection step [11]. To address whether the T6SS and the two VgrG modules play a role in the insect hemolymph, we mimicked a systemic infection by directly injecting cells of the CHA0 wild type or the ΔT6SS, ΔVgrG1a-mod, or ΔVgrG1b-mod mutants into the hemolymph of Pieris larvae. At 24 h postinjection, the percentage of surviving larvae sharply declined for all bacterial strains tested, dropping to levels of <20% at 30 h postinjection (Fig. 2b). No differences were observed between the insecticidal effects of the wild-type and mutant strains (Fig. 2b), indicating that the T6SS and the VgrG modules are not involved in the hemocoel phase of pathogenesis.

These findings support a significant role of the T6SS and the two VgrG modules along with their respective spike and effector proteins in insect pathogenesis of P. protegens. To our best knowledge, we provide here the first example for the implication of T6SS components in the pathogenicity of an environmental bacterium in a plant pest oral infection model. During the past years, the involvement of T6SS components in pathogenicity, be it direct by subverting host cellular function or indirect by aiding competitive host colonization, has been documented for a number of human and plant pathogenic bacteria [19, 24, 32, 57]. In several cases, mutants defective for T6SS components were reported to be impaired in persistence and interbacterial competitiveness during host interaction [19]. These reports prompted us to speculate that the T6SS and the VgrG modules might be required for the successful establishment of P. protegens in the intestinal tract of the insect and thus in competitive interactions with the commensal microbiota populating this environment.

The T6SS of P. protegens contributes to insect invasion

We examined whether the reduced insect pathogenicity of the T6SS and VgrG module-deficient mutants of P. protegens CHA0 is linked to a reduced capability of insect invasion following oral infection. To address this, we performed in vivo colonization assays with GFP-tagged variants of the bacteria and monitored their establishment in the gut, the hemolymph, and the excrements of P. brassicae larvae 24 h after oral infection. We deliberately chose this sampling time point because after this incubation period the first larvae started to die (Fig. 2a), implying that pseudomonads by then began to breach the gut epithelial barrier to gain the hemolymph, i.e., a crucial step of insect invasion at the onset of systemic infection. Compared with the wild type, the ΔT6SS mutant was only slightly, but significantly, impaired in its capacity to establish in the insect gut (Fig. 3a) but was strongly hampered in its capacity to establish in the hemolymph (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, only one of the two VgrG modules appeared to be implicated in insect invasion. Indeed, the ∆VgrG1a-mod mutant was largely unable to cross the gut epithelial barrier of the Pieris larvae to reach the hemolymph, whereas the ∆VgrG1b-mod mutant established in this compartment at wild-type levels (Fig. 3b). At this time point, both VgrG module mutants were not significantly affected in their gut colonization abilities (Fig. 3a). The analysis of the larval excrements indicated that, although ingested bacteria established in the insect gut, a significant fraction was cleared from the larvae at roughly the same cell numbers for all the strains tested (Fig. 3c).

Contribution of the T6SS and the VgrG modules of Pseudomonas protegens CHA0 to the colonization of the gut (a), the hemolymph (b), and the excrements (c) of larvae of Pieris brassicae following oral infection. Larvae were fed with a small piece of artificial diet containing 107 cells of green fluorescent protein-tagged variants of wild-type CHA0 or its ΔT6SS, ΔVgrG1a-mod, or ΔVgrG1b-mod mutants. The T6SS mutant (upper figure panels below insect scheme) and the VgrG module mutants (lower figure panels) were tested in separate experiments. Data show colony-forming unit counts of bacterial inoculants per mg of gut, hemolymph, or excrements of individual larvae determined at 24 h post oral infection. Each dot corresponds to one insect. Each box plot graph represents the median of the colonization levels calculated from three independent experiments that were carried out with nine larvae per treatment in each experiment. For the statistical analysis, a Student’s t test was performed to detect significant differences between the colonization levels of the wild-type CHA0 and the ∆T6SS mutant. Analysis of variance followed by Fisher’s least significant difference test was done to detect significant differences between the colonization levels of CHA0 and the VgrG1a and VgrG1b module mutants. ***P value < 0.001 and *P value < 0.05

Together these results indicate that the P. protegens T6SS has a significant role in gut colonization and preparation of the subsequent passage of the invader into the insect blood system. This is in line with recent reports about the contribution of T6SSs to gut invasion by enteropathogenic Salmonella, Shigella, and Vibrio [22, 23, 58, 59] and to host colonization by various other animal and plant pathogens [19, 24]. Hemolymph invasion by P. protegens CHA0 required a functional VgrG1a module. Interestingly, the VgrG1b module had no apparent role in insect colonization although it contributed significantly to insect pathogenicity. This suggests that P. protegens employs the two VgrG modules for different activities during pathogenesis of which that of the VgrG1a module is in competitive host colonization (see also following chapter), whereas the exact function of the VgrG1b module needs to be addressed in further studies. Bacteria equipped with T6SSs commonly harbor several VgrG modules along with specific effectors providing them with diverse functionalities during interaction with the host or other bacteria as exemplified by studies on P. aeruginosa [34, 60] and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli [61].

T6SS-mediated modification of the insect gut microbiome composition by P. protegens

Since the T6SS is known to function as major antibacterial weapon in pathogenic and commensal pseudomonads [24, 32, 34, 54, 60], we speculated that a potential role of the T6SS components in insect pathogenesis of P. protegens could be to eliminate commensal bacteria within the insect gut thereby facilitating the establishment of the invader in this niche and preparing the access to the gut epithelial barrier for passage into the hemocoel. To test this hypothesis, we performed a 16S RNA gene metagenomic analysis of the gut bacterial microbiota of P. brassicae at the larval stage, both in the presence and absence of P. protegens infection. Gut samples were analyzed after 24 h, i.e., at the same time insect colonization was monitored.

We sequenced 50 samples corresponding to five conditions (non-infected control; infection with wild-type CHA0 or ΔT6SS, ΔVgrG1a-mod, or ΔVgrG1b-mod mutants), with 10 samples per condition and four Pieris guts pooled per sample, and generated a total of 763,328 high-quality reads. On average, 12,722 high-quality filtered reads per sample were obtained. Sequences clustered into 160 different OTUs at a sequence identity cut-off of 97%. Rarefaction curves affirmed that the bacterial diversity in each sample was fully described (Fig. S2). The gut bacterial microbiome of healthy insects fed with non-inoculated diet was composed mainly of two bacterial phyla, i.e., Firmicutes (61.7%) and Proteobacteria (38.1%), while other phyla accounted for <0.2% of the total abundance (Fig. S3). The two bacterial families Enterococcaceae (58.7%) and Enterobacteriaceae (40.4%) were dominant in the gut of the P. brassicae larvae (Fig. 4a). Other bacterial families constituted <1% of the total bacterial abundance. More than 99.9% of the sequences affiliated to the Enterococcaceae family corresponded to a single OTU (denovo2983) associated with the genus Enterococcus (Table S6). In the Enterobacteriaceae, >96.1% of the sequences were associated with a single OTU (denovo3889) identified as genus Enterobacter. Our analysis provides the first data about the composition of the gut bacterial community of this important Lepidopteran plant pest. Previous studies specified Enterobacter sp. as dominant members of the larval gut microbiota of the related insect Pieris rapae [62, 63]. Enterobacter and Enterococcus are commonly found in the gut of Lepidopteran species [64, 65] and can provide beneficial services to their host. For example, they provide enzymatic functions that permit the detoxification of ingested phenolic plant defense compounds [66] or may act as bodyguards against bacterial pathogens invading the insect gut, e.g., by forming a protective biofilm on gut epithelial cells, by producing antimicrobials such as bacteriocins, or by inducing insect defenses [67, 68].

The T6SS contributes to changes induced in the gut microbiome composition of larvae of Pieris brassicae upon invasion by Pseudomonas protegens, impacting in particular on members of the Enterobacteriaceae family. a Gut bacterial composition following oral infection with wild-type CHA0 or its ΔT6SS, ΔVgrG1a-mod, or ΔVgrG1b-mod mutants. Larvae were fed with a small piece of artificial diet containing 107 inoculant cells and were dissected 24 h later to retrieve their guts. Control larvae were fed sterile diet. For each treatment, ten samples were prepared each containing the pooled guts from four larvae. DNA preparation and 16S rRNA gene-based metagenome sequencing were performed by GenoScreen (Lille, France). The gut bacterial composition was determined using non-transformed abundance data and the eight most abundant families are presented. Box plots illustrate the effects of wild-type CHA0 and the T6SS and VgrG module mutants on the median relative abundance of the Enterococcaceae (b) and Enterobacteriaceae (c) families in the insect guts. The data from the abundance matrix were transformed using total sum scaling and cumulative sum scaling normalization [44] and statistically analyzed using the CALYPSO pipeline [43]. **P value < 0.01, *P value < 0.05 (*) and end dot represents P value between 0.05 and 0.09

We analyzed to what extent invasion by P. protegens CHA0 or its T6SS-related mutants shapes the bacterial community in the P. brassicae gut. We retrieved a single abundant Pseudomonas OTU (denovo2125) from the gut samples of P. protegens-treated larvae, which corresponded to the inocula fed to the insects as verified by Blast analysis (100% identity) (Fig. 4a). The bacterial alpha diversity was not strongly affected by the presence of CHA0 or the T6SS-related mutants according to the Simpson and Chao indices (Fig. S4). The observed significant increase of the diversity at family and genus levels according to the Shannon–Weaver index (Fig. S4a) could be due to the reduction of the most abundant species following P. protegens invasion facilitating the detection of other taxa. Moreover, PCA indicated that the beta-diversity remained stable at the phylum and class levels for all the tested conditions (Figs. S5a-5b). However, at the family and genus levels, the control condition was distant from the other conditions, which reflects the effect of Pseudomonas invasion (Figs. S5c-5d). The dominance of two bacterial families (Enterococcaceae, Enterobacteriaceae) in the P. brassicae gut made it difficult to observe significant shifts in the remaining fraction of gut bacteria, which accounted for <1% of the total bacterial abundance in each condition. Hence, we focused our analysis on the impact of Pseudomonas invasion on the relative abundance of Enterococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae. Infection by P. protegens CHA0 caused a non-significant, mild decrease (P < 0.09) in the abundance of Enterococcaceae, which did not depend on the bacterial T6SS or VgrG modules (Fig. 4b). This finding is not unexpected, since the T6SS is thought to be ineffective against Gram-positive bacteria [32, 69,70,71]. By contrast, gut invasion by CHA0 resulted in a significant decline of the Enterobacteriaceae population in the insect intestines, which required the presence of a functional T6SS (Fig. 4c). The two VgrG modules might have contributed to the observed effect to some extent (Fig. 4c); however, the high variability among the samples did not allow us to statistically fully affirm this observation.

To confirm the findings of the 16S metagenomic analysis, we isolated bacteria from the gut of P. brassicae larvae in order to test them in in vitro competition assays against P. protegens CHA0 and the T6SS and VgrG module mutants. We repeatedly obtained colonies with two distinct morphologies, which we purified and identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing exclusively as Enterococcus sp. and Enterobacter sp., respectively. In confrontation assays against Enterobacter, the competitive index for the wild-type CHA0 was significantly higher than that for the ∆T6SS mutant (Fig. 5a). A similar effect was observed in the competition of Enterobacter with the ∆VgrG1a-mod mutant but not with the ∆VgrG1b-mod mutant. This indicates that P. protegens uses its T6SS and the VgrG1a module to outcompete Enterobacter. Contrarily, the T6SS and the VgrG modules did not contribute to the competitive advantage of P. protegens CHA0 in confrontation with Enterococcus (Fig. 5b). These findings are consistent with the T6SS-mediated reduction of Enterobacteriaceae by P. protegens in the gut microbiome of Pieris observed in the 16S metagenomic analysis (Fig. 4c).

The T6SS and the VgrG1a module contribute to interbacterial competition of Pseudomonas protegens CHA0 with Enterobacter sp. (a) but not with Enterococcus sp. (b) isolated from the gut of Pieris brassicae larvae. Competition of P. protegens wild-type CHA0, the ΔT6SS mutant, or the ΔVgrG1a-mod or ΔVgrG1b-mod mutants against Enterobacter sp. and Enterococcus sp. was assessed in filter spot assays. Colony-forming unit (CFU) quantifications were performed at t = 0 h and t = 24 h based on the antibiotic resistance profiles of the strains as detailed in Supplementary information. The competitive index (CI) of the competitor was calculated as follows: CI = [CFUcompetitor_24 h/CFUgut isolate_24 h]/[CFUcompetitor_0 h/CFUgut isolate_0 h]. Box plots represent data from three independent experiments, each with three replicate strain confrontations. Each dot corresponds to one confrontation. Data were analyzed using analysis of variance followed by honestly significant difference of Tukey. Statistical differences between the competitive indices of CHA0 mutants in confrontations with Enterobacter are indicated with letters a and b (P < 0.05). No statistical differences were found in the competitions with Enterococcus

Collectively, these results demonstrate that during invasion of P. brassicae larvae P. protegens uses the T6SS to modify the composition of the gut microbiome of the insect, thereby targeting and eliminating in particular bacteria of the genus Enterobacter that constitute one of the two dominant groups of commensals present in the intestinal tract of the plant pest. For Enterobacter killing, P. protegens appears to deploy the T6SS primarily with the associated VgrG1a module, which is equipped with the DNase effector RhsA. Commensal gut bacteria may form a protective layer at the gut surface, preventing systemic infections by entomopathogens [65, 68]. It is plausible that T6SS-mediated killing of commensal Enterobacter by P. protegens might locally disrupt this protective layer allowing the invader to reach the hemolymph and kill the insect (Fig. 6).

Interaction model between Pseudomonas protegens and the plant pest insect Pieris brassicae. Step 1: Oral infection; P. protegens cells (red) are ingested by the larvae. Step 2: P. protegens cells follow the path of food through the gut and establish in this insect compartment. In the gut, the microflora is mainly composed of Enterococcus sp. (green cells) and Enterobacter sp. (blue cells). Step 3: P. protegens cells cross the gut epithelial barrier by a yet unknown mechanism to reach the hemocoel. For this step, the bacteria need to find their way through the indigenous microflora that can aggregate onto the epithelial cells to form an additional protective layer [65, 68]. P. protegens uses its T6SS and the associated VgrG1a module, encompassing the VgrG1a spike along with the RhsA effector, to kill Enterobacter locally in the vicinity of the gut epithelial cells. Step 4: Once in the hemocoel, P. protegens starts to proliferate. Step 5: The bacteria produce virulence factors, among which is the entomotoxin Fit [13] that is specifically produced in the hemolymph of the insect [8, 16]. During invasion, a particular lipopolysaccharide decoration protects P. protegens against antimicrobial peptides (cecropins) produced by the host [15] and additional virulence factors such as hydrogen cyanide, cyclic lipopeptides, chitinase, and phospholipase aid to promote pathogenesis [5, 10, 11]. As soon as the bacteria invade the hemocoel compartment, the insect enters in an acute disease phase leading to its death within about 1 day. IM inner membrane, P periplasm, OM outer membrane

Conclusion

The findings of this study support the concept that pathogens deploy T6SS-based strategies to disrupt or otherwise manipulate the commensal microbiota of their host in order to facilitate host colonization as recently demonstrated for the human enteropathogens Salmonella Typhimurium [23] and V. cholerae [72,73,74]. We provide here the first example of the use of this strategy by an environmental plant-colonizing bacterium to successfully invade a plant pest insect and hence to gain access to an alternative host. We show evidence that the T6SS-mediated changes to the gut microbiome of the pest insect induced by P. protegens are linked to the functional requirement of the T6SS (i) to outcompete specific members of the commensal gut microbiota, (ii) to colonize the insect, and ultimately (iii) to promote the pathogenic relationship with the insect host. This is in line with recent work of Fast et al. [72] who demonstrated that T6SS activity against commensal gut bacteria supports the pathogenesis of V. cholerae. The present work significantly expands our knowledge about the virulence strategies and weaponry that contribute to the capacity of a group of plant-associated pseudomonads to orally infect and kill plant pest insects. Genomic and mutational analyses carried out since the first discovery of the potent insecticidal activity in these pseudomonads [13] so far have identified secreted toxins (Fit toxin, rhizoxins, cyclic lipopeptides, hydrogen cyanide) and lytic enzymes (chitinase, phospholipase) as bacterial determinants promoting insect pathogenesis, i.e., all virulence factors likely deployed by the bacteria to cause direct damage to the insect host at some point during invasion [5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 16]. In turn, the bacteria appear to rely on specific cell surface decorations to escape the insect immune defense [10, 15]. Here we identified T6SS-mediated manipulation of the gut microbiota as further strategy to promote insect pathogenesis in the repertoire of insecticidal pseudomonads. In our study, P. protegens uses the T6SS to target a dominant group of commensals, i.e., Enterobacter sp., in the gut of the investigated plant pest. By eliminating part of the population of these commensals, P. protegens possibly improves the access to the gut epithelial barrier for the subsequent passage into the hemolymph. Collectively, all these findings advance our understanding of the infection process and allow us to further detail the interaction model between Pseudomonas and the insect as illustrated in Fig. 6. Since P. protegens is also known as an efficient root colonizer and biocontrol agent of crop diseases [4, 6], it will be of interest to study to which extent this bacterium deploys its T6SS weaponry to competitively colonize plants, i.e., its original host.

References

Garrido-Sanz D, Arrebola E, Martínez-Granero F, García-Méndez S, Muriel C, Blanco-Romero E, et al. Classification of isolates from the Pseudomonas fluorescens complex into phylogenomic groups based in group-specific markers. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:413.

Vacheron J, Desbrosses G, Bouffaud M-L, Touraine B, Moënne-Loccoz Y, Muller D, et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and root system functioning. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:356.

Mauchline TH, Malone JG. Life in earth - the root microbiome to the rescue? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2017;37:23–28.

Kupferschmied P, Maurhofer M, Keel C. Promise for plant pest control: root-associated pseudomonads with insecticidal activities. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:287.

Flury P, Aellen N, Ruffner B, Péchy-Tarr M, Fataar S, Metla Z, et al. Insect pathogenicity in plant-beneficial pseudomonads: phylogenetic distribution and comparative genomics. ISME J. 2016;10:2527–42.

Haas D, Défago G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:307–19.

Haas D, Keel C. Regulation of antibiotic production in root-colonizing Pseudomonas spp. and relevance for biological control of plant disease. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2003;41:117–53.

Péchy-Tarr M, Borel N, Kupferschmied P, Turner V, Binggeli O, Radovanovic D, et al. Control and host-dependent activation of insect toxin expression in a root-associated biocontrol pseudomonad. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:736–50.

Ruffner B, Péchy-Tarr M, Ryffel F, Hoegger P, Obrist C, Rindlisbacher A, et al. Oral insecticidal activity of plant-associated pseudomonads. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:751–63.

Keel C. A look into the toolbox of multi-talents: insect pathogenicity determinants of plant-beneficial pseudomonads. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:3207–9.

Flury P, Vesga P, Péchy-Tarr M, Aellen N, Dennert F, Hofer N, et al. Antimicrobial and insecticidal: cyclic lipopeptides and hydrogen cyanide produced by plant-beneficial Pseudomonas strains CHA0, CMR12a, and PCL1391 contribute to insect killing. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:100.

Loper JE, Henkels MD, Rangel LI, Olcott MH, Walker FL, Bond KL, et al. Rhizoxin analogs, orfamide A and chitinase production contribute to the toxicity of Pseudomonas protegens strain Pf-5 to Drosophila melanogaster. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:3509–21.

Péchy-Tarr M, Bruck DJ, Maurhofer M, Fischer E, Vogne C, Henkels MD, et al. Molecular analysis of a novel gene cluster encoding an insect toxin in plant-associated strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:2368–86.

Rangel LI, Henkels MD, Shaffer BT, Walker FL, Davis EW, Stockwell VO, et al. Characterization of toxin complex gene clusters and insect toxicity of bacteria representing four subgroups of Pseudomonas fluorescens. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0161120.

Kupferschmied P, Chai T, Flury P, Blom J, Smits THM, Maurhofer M, et al. Specific surface glycan decorations enable antimicrobial peptide resistance in plant-beneficial pseudomonads with insect-pathogenic properties. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:4265–81.

Kupferschmied P, Péchy-Tarr M, Imperiali N, Maurhofer M, Keel C. Domain shuffling in a sensor protein contributed to the evolution of insect pathogenicity in plant-beneficial Pseudomonas protegens. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003964.

Basler M. Type VI secretion system: secretion by a contractile nanomachine. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370:pii20150021.

Cianfanelli FR, Monlezun L, Coulthurst SJ. Aim, load, fire: The type VI secretion system, a bacterial nanoweapon. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:51–62.

Hachani A, Wood TE, Filloux A. Type VI secretion and anti-host effectors. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;29:81–93.

Ho BT, Dong TG, Mekalanos JJ. A view to a kill: the bacterial type VI secretion system. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:9–21.

Nguyen VS, Douzi B, Durand E, Roussel A, Cascales E, Cambillau C. Towards a complete structural deciphering of type VI secretion system. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2018;49:77–84.

Fu Y, Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. Tn-Seq analysis of Vibrio cholerae intestinal colonization reveals a role for T6SS-mediated antibacterial activity in the host. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:652–63.

Sana TG, Flaugnatti N, Lugo KA, Lam LH, Jacobson A, Baylot V, et al. Salmonella typhimurium utilizes a T6SS-mediated antibacterial weapon to establish in the host gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E5044–51.

Bernal P, Llamas MA, Filloux A. Type VI secretion systems in plant-associated bacteria. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20:1–15.

Ma L-S, Hachani A, Lin J-S, Filloux A, Lai E-M. Agrobacterium tumefaciens deploys a superfamily of type VI secretion DNase effectors as weapons for interbacterial competition in planta. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:94–104.

Filloux A, Freemont P. Structural biology: baseplates in contractile machines. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16104.

Silverman JM, Brunet YR, Cascales E, Mougous JD. Structure and regulation of the type VI secretion system. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:453–72.

Alcoforado Diniz J, Liu Y-C, Coulthurst SJ. Molecular weaponry: diverse effectors delivered by the type VI secretion system. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17:1742–51.

Cianfanelli FR, Alcoforado Diniz J, Guo M, De Cesare V, Trost M, Coulthurst SJ. VgrG and PAAR proteins define distinct versions of a functional type VI secretion system. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005735.

Shneider MM, Buth SA, Ho BT, Basler M, Mekalanos JJ, Leiman PG. PAAR-repeat proteins sharpen and diversify the type VI secretion system spike. Nature. 2013;500:350–53.

Durand E, Cambillau C, Cascales E, Journet L. VgrG, Tae, Tle, and beyond: the versatile arsenal of type VI secretion effectors. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:498–507.

Russell AB, Peterson SB, Mougous JD. Type VI secretion system effectors: poisons with a purpose. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:137–48.

Whitney JC, Beck CM, Goo YA, Russell AB, Harding B, De Leon JA, et al. Genetically distinct pathways guide effector export through the type VI secretion system. Mol Microbiol. 2014;92:529–42.

Hachani A, Allsopp LP, Oduko Y, Filloux A. The VgrG proteins are ‘à la carte’ delivery systems for bacterial type VI effectors. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:17872–84.

Winsor GL, Griffiths EJ, Lo R, Dhillon BK, Shay JA, Brinkman FSL. Enhanced annotations and features for comparing thousands of Pseudomonas genomes in the Pseudomonas genome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D646–53.

Marchler-Bauer A, Bo Y, Han L, He J, Lanczycki CJ, Lu S, et al. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D200–D203.

Finn RD, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, Bateman A, Bork P, Bridge AJ, et al. InterPro in 2017—beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D190–D199.

Hachani A, Lossi NS, Hamilton A, Jones C, Bleves S, Albesa-Jové D, et al. Type VI secretion system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa secretion and multimerization of VgrG proteins. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12317–27.

Hood RD, Singh P, Hsu F, Güvener T, Carl MA, Trinidad RRS, et al. A type VI secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targets a toxin to bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:25–37.

Pissaridou P, Allsopp LP, Wettstadt S, Howard SA, Mavridou DAI, Filloux A. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa T6SS-VgrG1b spike is topped by a PAAR protein eliciting DNA damage to bacterial competitors. PNAS. 2018;115:12519–12524.

Martínez-García E, de Lorenzo V. Engineering multiple genomic deletions in Gram-negative bacteria: analysis of the multi-resistant antibiotic profile of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:2702–16.

David WAL, Gardiner BOC. Rearing Pieris brassicae L. larvae on a semi-synthetic diet. Nature. 1965;207:882–883.

Zakrzewski M, Proietti C, Ellis JJ, Hasan S, Brion M-J, Berger B, et al. Calypso: a user-friendly web-server for mining and visualizing microbiome–environment interactions. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:782–3.

Paulson JN, Stine OC, Bravo HC, Pop M. Robust methods for differential abundance analysis in marker gene surveys. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1200–2.

Filloux A, Hachani A, Bleves S. The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. Microbiology. 2008;154:1570–83.

Mougous JD, Cuff ME, Raunser S, Shen A, Zhou M, Gifford CA, et al. A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science. 2006;312:1526–30.

Hassan KA, Johnson A, Shaffer BT, Ren Q, Kidarsa TA, Elbourne LDH, et al. Inactivation of the GacA response regulator in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 has far-reaching transcriptomic consequences. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:899–915.

Loper JE, Hassan KA, Mavrodi DV, Davis EW, Lim CK, Shaffer BT, et al. Comparative genomics of plant-associated Pseudomonas spp.: insights into diversity and inheritance of traits involved in multitrophic interactions. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002784.

Basler M, Ho BT, Mekalanos JJ. Tit-for-tat: type VI secretion system counterattack during bacterial cell-cell interactions. Cell. 2013;152:884–94.

Cascales E, Cambillau C. Structural biology of type VI secretion systems. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:1102–11.

Zoued A, Brunet YR, Durand E, Aschtgen M-S, Logger L, Douzi B, et al. Architecture and assembly of the type VI secretion system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:1664–73.

Ruffner B, Péchy-Tarr M, Höfte M, Bloemberg G, Grunder J, Keel C, et al. Evolutionary patchwork of an insecticidal toxin shared between plant-associated pseudomonads and the insect pathogens Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:609.

Ma J, Pan Z, Huang J, Sun M, Lu C, Yao H. The Hcp proteins fused with diverse extended-toxin domains represent a novel pattern of antibacterial effectors in type VI secretion systems. Virulence. 2017;8:1189–1202.

Tang JY, Bullen NP, Ahmad S, Whitney JC. Diverse NADase effector families mediate interbacterial antagonism via the type VI secretion system. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:1504–14.

Unterweger D, Kostiuk B, Pukatzki S. Adaptor proteins of type VI secretion system effectors. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:8–10.

Bondage DD, Lin J-S, Ma L-S, Kuo C-H, Lai E-M. VgrG C terminus confers the type VI effector transport specificity and is required for binding with PAAR and adaptor-effector complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E3931–40.

Kapitein N, Mogk A. Deadly syringes: type VI secretion system activities in pathogenicity and interbacterial competition. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:52–8.

Anderson MC, Vonaesch P, Saffarian A, Marteyn BS, Sansonetti PJ. Shigella sonnei encodes a functional T6SS used for interbacterial competition and niche occupancy. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:769–776.e3.

Joshi A, Kostiuk B, Rogers A, Teschler J, Pukatzki S, Yildiz FH. Rules of engagement: the type VI secretion system in Vibrio cholerae. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:267–79.

Sana TG, Berni B, Bleves S. The T6SSs of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAO1 and their effectors: beyond bacterial-cell targeting. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016;6:61.

Ma J, Sun M, Pan Z, Lu C, Yao H. Diverse toxic effectors are harbored by vgrG islands for interbacterial antagonism in type VI secretion system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2018;1862:1635–43.

Broderick NA, Robinson CJ, McMahon MD, Holt J, Handelsman J, Raffa KF. Contributions of gut bacteria to Bacillus thuringiensis-induced mortality vary across a range of Lepidoptera. BMC Biol. 2009;7:11.

Robinson CJ, Schloss P, Ramos Y, Raffa K, Handelsman J. Robustness of the bacterial community in the cabbage white butterfly larval midgut. Microb Ecol. 2010;59:199–211.

Tang X, Freitak D, Vogel H, Ping L, Shao Y, Cordero EA, et al. Complexity and variability of gut commensal microbiota in polyphagous lepidopteran larvae. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36978.

Paniagua Voirol LR, Frago E, Kaltenpoth M, Hilker M, Fatouros NE. Bacterial symbionts in Lepidoptera: their diversity, transmission, and impact on the host. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:556.

Xia X, Gurr GM, Vasseur L, Zheng D, Zhong H, Qin B, et al. Metagenomic sequencing of diamondback moth gut microbiome unveils key holobiont adaptations for herbivory. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:663.

Shao Y, Chen B, Sun C, Ishida K, Hertweck C, Boland W. Symbiont-derived antimicrobials contribute to the control of the Lepidopteran gut microbiota. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24:66–75.

Engel P, Moran NA. The gut microbiota of insects – diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:699–735.

Chou S, Bui NK, Russell AB, Lexa KW, Gardiner TE, LeRoux M, et al. Structure of a peptidoglycan amidase effector targeted to Gram-negative bacteria by the type VI secretion system. Cell Rep. 2012;1:656–64.

MacIntyre DL, Miyata ST, Kitaoka M, Pukatzki S. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system displays antimicrobial properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19520–4.

Schwarz S, West TE, Boyer F, Chiang W-C, Carl MA, Hood RD, et al. Burkholderia type VI secretion systems have distinct roles in eukaryotic and bacterial cell interactions. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001068.

Fast D, Kostiuk B, Foley E, Pukatzki S. Commensal pathogen competition impacts host viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:7099–104.

Logan SL, Thomas J, Yan J, Baker RP, Shields DS, Xavier JB, et al. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system can modulate host intestinal mechanics to displace gut bacterial symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:3779–87.

Zhao W, Caro F, Robins W, Mekalanos JJ. Antagonism toward the intestinal microbiota and its effect on Vibrio cholerae virulence. Science. 2018;359:210–3.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the group of Philippe Reymond at the Department of Plant Molecular Biology of the University of Lausanne for help with rearing Pieris brassicae and with the development of the artificial diet-based feeding assay. We thank the Biocommunications group (Consuelo De Moraes), Department of Environmental System Science, ETH Zurich for providing eggs of Pieris brassicae.

Sources of support (grants/equipment)

This study was supported by grant 31003A-159520 from the Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vacheron, J., Péchy-Tarr, M., Brochet, S. et al. T6SS contributes to gut microbiome invasion and killing of an herbivorous pest insect by plant-beneficial Pseudomonas protegens. ISME J 13, 1318–1329 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-019-0353-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-019-0353-8

This article is cited by

-

The role of the type VI secretion system in the stress resistance of plant-associated bacteria

Stress Biology (2024)

-

Changes in structure and assembly of a species-rich soil natural community with contrasting nutrient availability upon establishment of a plant-beneficial Pseudomonas in the wheat rhizosphere

Microbiome (2023)

-

Isolation, identification and pathogenicity of local entomopathogenic bacteria as biological control agents against the wild cochineal Dactylopius opuntiae (Cockerell) on cactus pear in Morocco

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Relation of pest insect-killing and soilborne pathogen-inhibition abilities to species diversification in environmental Pseudomonas protegens

The ISME Journal (2023)

-

Tomato defences modulate not only insect performance but also their gut microbial composition

Scientific Reports (2023)