Abstract

Island biogeography theory is one of the most influential paradigms in ecology. That island characteristics, including remoteness, can profoundly modulate biological diversity has been borne out by studies of animals and plants. By contrast, the processes influencing microbial diversity in island systems remain largely undetermined. We sequenced arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungal DNA from plant roots collected on 13 islands worldwide and compared AM fungal diversity on islands with existing data from mainland sites. AM fungal communities on islands (even those >6000 km from the closest mainland) comprised few endemic taxa and were as diverse as mainland communities. Thus, in contrast to patterns recorded among macro-organisms, efficient dispersal appears to outweigh the effects of taxogenesis and extinction in regulating AM fungal diversity on islands. Nonetheless, AM fungal communities on more distant islands comprised a higher proportion of previously cultured and large-spored taxa, indicating that dispersal may be human-mediated or require tolerance of significant environmental stress, such as exposure to sunlight or high salinity. The processes driving large-scale patterns of microbial diversity are a key consideration for attempts to conserve and restore functioning ecosystems in this era of rapid global change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Islands have figured prominently in the development of ecological theory (e.g., [1,2,3]). With their theory of island biogeography, MacArthur and Wilson [2] argued that the equilibrium number of species inhabiting an island or other isolated habitat patch is determined by the balance between immigration and speciation on one hand and emigration and extinction on the other. They also suggested that island characteristics—notably the size of an island and its remoteness from potential source communities (i.e., mainlands)—modulate the importance of these processes, such that a positive species–area relationship leads to higher species richness on large islands, while a negative species–isolation relationship results in lower richness on remote islands. Descriptive and rarely experimental studies have lent empirical support to the theory and have confirmed both species–area and species–isolation relationships [4]. The theory has become one of the most influential ecological paradigms and is central to several applied (e.g., conservation ecology) and theoretical (e.g., metapopulation and metacommunity theories) disciplines [5]. Moreover, the study of island systems continues to provide new insights into a range of ecological questions, including those related to the process of community assembly [6].

Most empirical tests of island biogeography theory have focused on animals or plants, and attempts to understand equivalent processes acting on micro-organisms have mainly studied habitat fragmentation at the landscape level or below [7,8,9,10]. Despite notable work on certain taxonomic groups (e.g., Fungi, [11]), information about the large-scale biogeography of micro-organisms is lacking [12]. One group of micro-organisms whose global biogeography has been relatively well characterised is the arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi [13, 14]. AM fungi (subphylum Glomeromycotina; [15]) live in association with the roots of about 80% of terrestrial plant species, gaining plant-assimilated carbon while supplying their hosts with nutrients (mainly P) and resistance to abiotic stress and pathogens [16]. At small scales, the diversity patterns of these essential plant symbionts are influenced by both niche and neutral processes [17, 18], including some degree of dispersal limitation, i.e., an inability of taxa to reach potentially suitable habitats in a given time frame [19]. Nonetheless, AM fungi are found on all continents and many approximately species-level phylogroups (phylogenetically defined groupings of taxa described by DNA sequences) have been shown to exhibit wide distributions, frequently spanning multiple continents [13, 20]. AM fungi are soil-dwelling organisms and may disperse using spores or by transport of hyphal or colonised root fragments [16]. Limited evidence exists for a number of potential dispersal vectors (including wind [21], invertebrates [22], mammals [23], birds [24] and water [25]), but the relative importance of each remains unquantified. It is even unclear whether the wide distributions of AM fungal taxa are the result of incremental small-scale movement or long-distance dispersal events.

Evidence from plants indicates that taxon arrival and persistence on isolated islands is correlated with aspects of life history, such as the traits influencing propagule production, dispersal and establishment ([4, 26]; though see ref. [27]). For example, pteridophytes—a group of wind-dispersed plants with very small diaspores—are randomly distributed throughout the Galápagos islands, while the distributions of comparatively larger-seeded plants are correlated with island size and isolation within the archipelago [28, 29]. By contrast, assigning life history characteristics to micro-organisms in environmental samples remains extremely challenging (though metagenomic studies represent a promising avenue; [30, 31]), and there have been few attempts to connect micro-organism life history and biogeography [32,33,34].

Some AM fungal taxa produce spores, but DNA-based surveys of environmental samples have revealed a significant proportion of AM fungal diversity that does not correspond to known sporulating taxa [35]. While some taxa known only from environmental DNA may yet be shown to produce spores, abundantly sporulating and easily cultured taxa (hereafter ‘cultured’) are presumed to be relatively efficient dispersers and have been broadly characterised as ruderals (i.e., tolerant of disturbance; [36], [37]). Among such taxa, certain spore characteristics can also be used to infer a more detailed life history strategy (e.g., spore size). This means that a small number of life history characteristics are available for a fraction of recorded AM fungal diversity, but that alternative traits and methods (e.g., DNA-based) are required for a complete survey of naturally occurring AM fungal communities.

All else being equal, smaller fungal propagules are more efficiently transported by wind [38, 39]. Therefore, if wind is an important dispersal vector for AM fungi, one might expect cultured (i.e., known to be spore-producing) and specifically small-spored AM fungal taxa to predominate on islands. Conversely, among vascular plants and other fungi, large propagules are associated with establishment success in harsh conditions [40, 41]. This may equally apply to AM fungal spores; for instance, large-spored Gigaspora are capable of multiple germinations [42], and such spores stay viable for several years and through changing environmental conditions [43, 44]. In addition, vascular plants may arrive at islands via floating in seawater [29, 45], in which case the plant propagules are often relatively large [46]. If transport in seawater, or other long-distance dispersal mechanisms that impose significant stress, are important for AM fungi, large-spored, cultured taxa might be expected to predominate on islands. Finally, the origin of fungal propagules may be an important determinant of island AM fungal life history characteristics. Human-mediated transport might favour cultured taxa since these are known to be associated with anthropogenic habitats [37].

We sampled AM fungal communities on oceanic islands worldwide, allowing us to test hypotheses related to AM fungal biogeography and dispersal. We predicted that diversity or trait responses to island conditions should be most apparent on small or isolated islands, reflecting species–area and species–isolation relationships. Furthermore, we expected that the effects of isolation on the prevalence of culturable taxa and spore size estimates in AM fungal communities should provide evidence about the dispersal characteristics of AM fungi. If AM fungal dispersal is largely conducted through incremental small-scale dispersal events, then island isolation should represent a significant barrier to dispersal and consequently island community composition should be stochastic and characterised by lower diversity and greater endemism than mainland communities. Conversely, if AM fungi are efficient long-distance dispersers, then the taxon pools capable of colonising island and mainland communities should be similar, and endemism should not be particularly pronounced on islands. If small-spored taxa predominate on islands, this might indicate an important role of wind dispersal. However, if large-spored taxa predominate, it might indicate a dispersal or establishment route that requires significant stress tolerance (e.g., seawater transport). Equally, a predominance of cultured AM fungal taxa on islands might indicate that human-mediated transport plays a role.

Materials and methods

Sampling island AM fungal communities

We collected samples from 13 islands worldwide: in the Arctic Ocean (Svalbard), Baltic Sea (Öland and Saaremaa), Caribbean (Guadeloupe), Pacific Ocean (New Caledonia, Tikehau, Tahiti), Tasman sea (Tasmania), Atlantic Ocean (Iceland, Sal, Santiago) and Mediterranean sea (Mallorca, Crete) (Fig. 1; Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table S1). All islands besides Mallorca, Tasmania and possibly New Caledonia were of oceanic (i.e., volcanic) origin or were submerged following isolation from a continental mainland (Supplementary Methods). This means that vicariance was not a factor in the formation of most of the island AM fungal communities under investigation; rather taxa must have colonised following island formation. We compared island data with an existing global mainland data set, collected and analysed in an identical manner by Davison et al. [13].

Map of study island and mainland sites used for comparison. Island sites sampled in this study are shown by red symbols. Mainland sites from Davison et al. [13] are shown by black symbols; large symbols indicate those mainland sites that were closest to an island site and were paired in certain analyses (see Fig. S1)

On each island, we identified one or two sites in the locally present ecosystems that were least disturbed by human activities. Following the design used by Davison et al. [13], we sampled two plots at each study site, representing visually homogeneous vegetation and habitat conditions. The plots were approximately 30 × 30 m, and the distance between plots generally ranged between several hundreds of metres and several km. In each plot, we generally selected four locally abundant AM plant species and excavated four randomly chosen individuals of each plant species (Supplementary Table S1). However, fewer species were sampled on Tikehau and Tahiti, and in these cases more individuals (up to 10 per species) were sampled (Supplementary Table S1). Soil and other material adhering to plant roots was carefully removed by hand. A root sample of approximately 20 cm was wrapped in tissue paper and placed in a plastic bag containing silica gel. A pooled topsoil sample (approximately 500 g) comprising 10 individual samples was collected from all plots except Tasmania. For details of soil chemical analyses and other recorded environmental variables, see Supplementary Methods and Table S1.

Molecular methods and bioinformatics

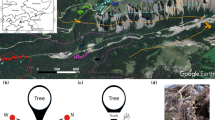

We followed the molecular methods and bioinformatics used by Davison et al. [13]. A full description of these methods is presented in the Supplementary Methods. Briefly, we amplified AM fungal DNA (partial SSU rRNA gene) from root samples and subjected this to high-throughput (454) sequencing. We used BLAST [47] to match (i) the obtained ‘island’ sequence reads and (ii) the ‘mainland’ sequencing reads from Davison et al. [13] against known virtual taxa (VT; i.e., phylogroups) from the MaarjAM database ([48]; Supplementary Table S2). Using the same classification criteria used to define VT in MaarjAM, we then searched for previously unrecorded VT among the reads not matching an existing VT (Supplementary Table S2). We used the MaarjAM database to identify those VT that could be associated with an AM fungal morphospecies (i.e., species described on the basis of spore traits from a cultured organism; Supplementary Table S3). VT were defined as ‘cultured’ if they contained sequences derived from an isolate of known morphospecies identity. For cultured VT, we estimated a mean spore diameter based on the spore characteristics of component morphospecies (Supplementary Table S3). Finally, we coestimated evolutionary timescale and phylogeny for all known VT using BEAST [49]. The phylogeny, VT-morphospecies associations and spore diameter estimates are shown on Fig. 2. Sequencing data generated in this study have been submitted to EMBL (study accession PRJEB20015). This includes raw sequencing reads from all runs and a set of representative sequences matched against different VT (where available, two sequences per VT from each host plant in each plot; accessions LT828649–LT835058). Sequencing data from Davison et al. [13] used for reanalysis in this study are also available from EMBL (study accession PRJEB9764).

Bayesian phylogeny of Glomeromycotina virtual taxa (VT; SSU rRNA gene sequences). The relative abundance of reads derived from each VT is shown for mainland and island sites collectively and for each island separately (i.e., symbol areas sum to 1 within each column). Islands are ordered by increasing remoteness. Blue symbols indicate islands of oceanic origin; green symbols indicate islands of continental origin. VT containing sequences from known morphospecies (cultured) are indicated by an open symbol. A mean estimate of spore diameter could be calculated for some cultured VT (shown in barplot in right-hand panel)

Statistical analysis

We primarily focused on AM fungal diversity and life history characteristics derived from taxon lists (i.e., presence–absence), since the predictions of island biogeography theory mainly relate to the distribution rather than abundance of organisms. However, since organism abundance is expected to influence the functional properties of communities and ecosystems [50], we included several analogous approaches incorporating the relative abundance of VT in samples (estimated from the relative abundance of sequencing reads). We expected these parallel analyses to provide an indication of whether island biogeographic processes were reflected by ecologically relevant changes in community assembly.

For each island and mainland site, we estimated local endemism by calculating the number of VT that were recorded at the site and nowhere else. We also calculated an index of VT distribution for each site: the mean number of other sites globally occupied by the VT present.

For further analysis of AM fungal communities on islands and in the mainland set, we pooled the replicates within each host plant species per plot. Based on these plant-species-level community estimates (hereafter referred to as samples), we investigated community diversity, composition and trait characteristics using two modelling approaches: (i) island biogeography models (IB) only containing the explanatory variables ‘set’ (island vs. mainland set) or ‘island area’ and ‘island remoteness’; and (ii) island biogeography and environment models (IBE), which in addition to IB variables incorporated all available explanatory variables related to soil chemistry (pH, N, P), altitude and climate (mean annual precipitation (MAP), mean annual temperature (MAT). The purpose of the IBE models was to test the importance of island biogeographic processes after accounting for measured environmental differences among island and mainland samples. In all analyses besides those describing multivariate community composition, the variable ‘island remoteness’ was calculated as the Haversine distance (accounting for the curvature of the earth) separating each island from the closest continental coastline. In analyses of composition, each island site was paired with the closest measured mainland site (from [13]), and in these cases, geographic separation was calculated as the Haversine distance separating the paired sites. This measure was highly correlated with the distance of each island from the closest continent (Pearson’s r = 0.97, P < 0.001), though the rank order of islands changed.

We used PERMANOVA (function adonis from R package vegan [51]) with Sørensen (abundance-unweighted) and Bray-Curtis (abundance-weighted) distance to estimate compositional differences between island and mainland samples. We also calculated mean pairwise distances between samples from each island and a paired mainland site (the geographically closest mainland site to each island; Supplementary Figure S1). These distances were regressed against island area and the geographic distance separating each island from its paired site. To place the effect of geographic separation on compositional distance in the context of compositional decay over continental land masses, we also included data points corresponding to all pairwise distances (compositional and geographic) between mainland sites within individual continents in the geographic distance analysis. We visualised community composition using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS; function metaMDS from vegan; Sørensen distance, stress = 0.19).

For all island and mainland samples, we calculated VT richness and two diversity estimators that incorporate organism abundance: the asymptotic estimators for exponential Shannon and reciprocal Simpson diversity [52]. We did not generate an extrapolated estimate of richness (Chao), since this estimator is not reliable beyond double the observed sample size and the corresponding sample completeness; by contrast, the abundance-sensitive diversity measures are generally robust in extrapolation to an asymptote [52]. Among the Pacific island samples, where as many as 10 replicates were sampled per host plant species, we randomly selected 4 replicates per host prior to calculating diversity, in order to balance sampling effort with the rest of the data set (Supplementary Table S1).

We also characterised each sample in terms of certain taxonomic and life history characteristics of its component VT: the proportion of VT in each sample that belonged to the order Glomerales; the phylogenetic diversity (mean pairwise distance; function mpd from R package picante; [53]) of VT present in each sample; the proportion of cultured VT in each sample (i.e., representing cultured morphospecies); and the mean spore diameter of VT in each sample, using those VT for which we had an estimate of this measure. We calculated these taxonomic and life history indices using abundance-unweighted (using presence–absence data) and abundance-weighted (using the relative abundance of VT reads in samples) approaches. We used linear or generalised linear mixed models [54, 55] to assess how the community parameters (diversity and taxonomic or life history characteristics) differed between island and mainland samples and in relation to island remoteness and area. A detailed description of the modelling and randomisation procedures used for inference is presented in the Supplementary Methods.

Results

Taxon distribution and endemism

We recorded 248 AM fungal VT (i.e., phylogenetically defined sequence groupings) from plant root samples collected on 13 islands worldwide (Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) and 252 VT from reanalysis of Davison et al.’s [13] global mainland data set (also derived from plant roots and generated using identical field and bioinformatics methods; Supplementary Table S2). Two-hundred and twenty-three VT were recorded from both island and mainland sites, with 25 and 29 VT recorded solely from island and mainland sites, respectively. Of 6 previously unrecorded VT, all were recorded from multiple sites, though the new Claroideoglomus VT (IS.Cl1) was only present on the remote atoll of Tikehau in the South Pacific. Island sites were more likely than mainland sites to harbour taxa that were recorded only at a single study site (i.e., endemic within our data set): 33% of island sites contained 1–4 such endemic VT; whereas 11% of mainland sites contained 1 such endemic VT (Wilcoxon Z = 2.09, P = 0.03). Correspondingly, island sites were composed of slightly less well distributed VT than mainland sites (mean ± SE number of other sites occupied by component VT: island sites = 15.4 ± 0.3, mainland sites = 16.4 ± 0.2; F1,51 = 7.06, P = 0.01).

Island vs. mainland communities

There was a systematic but minor difference in AM fungal community composition between island and mainland samples, both in models excluding (IB) and accounting for (IBE) measured environmental characteristics (PERMANOVA; Sørensen distance, IB model R2 = 0.01, P = 0.004; IBE model R2 = 0.01, P = 0.005; Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figure S2). Models accounting for VT relative abundance indicated a similar pattern (PERMANOVA; Bray-Curtis distance, IB model R2 = 0.01, P = 0.004; IBE model R2 = 0.01, P = 0.005). However, island and mainland samples were dominated by the same taxa (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figure S3) and did not differ significantly in any measure of diversity (Fig. 3 and Table 1) or in the level of any measured trait connected with taxonomy or life history (Glomerales proportion, mean pairwise genetic distance, proportion of cultured taxa, mean spore diameter; Table 1).

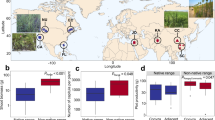

Estimates of diversity in island and mainland arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. Three different diversity metrics are presented: a raw richness; and the asymptotic estimators for b exponential Shannon diversity; and c reciprocal Simpson diversity. The violin plots show the distribution of diversity values (filled curves); as well as the median value (white point), quartiles (black bar) and range (whiskers). Diversity was measured at the level of host plant species per plot (i.e., pooling up to 4 individual samples)

Island remoteness and size

Mean compositional distance (Sørensen) between AM fungal communities was positively related to the geographic distance separating them (Fig. 4; IB model, Prand < 0.001; IBE model, Prand < 0.001), and was greater between island and paired mainland sites than between mainland sites an equivalent distance apart (Fig. 4; IB model, Prand < 0.001; IBE model, Prand < 0.001). Relationships based on relative abundance (Bray-Curtis distance) were similar (Supplementary Figure S4). Mean compositional distance between paired island and mainland sites did not vary significantly in relation to island area (IB model, Prand = 0.06; IBE model, Prand = 0.48).

Mean compositional distance (Sørensen) between root-associated AM fungal communities as a function of the geographic distance (Haversine; natural log km) separating them. Points represent community pairs: islands and paired mainland sites (i.e., the geographically closest mainland site; large blue or green points) or pairs of mainland sites within the same continent (small grey points). a Island biogeography (IB) model not accounting for environmental characteristics; b island biogeography and environment (IBE) model accounting for environmental characteristics. Separate regression lines are shown for island–mainland (solid) and mainland–mainland (dashed) points. Compositional distances in the IBE model were calculated among the residuals of a distance-based redundancy analysis model against measured environmental variables. Blue symbols indicate islands of oceanic origin; green symbols indicate islands of continental origin

No measures of diversity differed significantly in relation to island remoteness or island area (Table 1). However, island remoteness significantly explained the proportion of Glomerales VT in samples (lower on distant islands; IB and IBE models), the unweighted phylogenetic diversity of samples (higher on distant islands; IBE model), the proportion of cultured VT in samples (higher on distant islands; IBE model) and the mean spore diameter of VT in samples (higher on distant islands; IB model; Table 1; Fig. 5). Island area explained variation in the proportion of Glomerales VT in samples (lower on large islands; IBE model; Table 1; Supplementary Figure S5). Island remoteness and area both significantly explained the mean spore diameter of VT in samples in abundance-weighted analyses (greater on small and distant islands; Supplementary Table S4; Supplementary Figures S4 and S5).

Relationship between island remoteness (natural log Haversine distance in km from the closest mainland) and several (abundance-unweighted) taxonomic and life history characteristics of plant root-associated AM fungal communities: a the mean proportion of Glomerales VT, b the mean pairwise phylogenetic distance (MPD) between VT, c the proportion of cultured VT, and d the mean spore diameter of VT. Lines show predicted values from island biogeography (IB) generalised linear mixed models. Blue symbols indicate islands of oceanic origin; green symbols indicate islands of continental origin. VT virtual taxa (phylogenetically defined DNA-based taxa)

Discussion

Here, we report a first attempt to measure oceanic island biogeographic patterns in a group of microbial organisms: plant symbiotic AM fungi. We recorded only very minor compositional differences between island and mainland fungal communities and found no evidence of high endemism on islands or significant differences between mainland and island fungal communities in terms of diversity or characteristics reflecting taxonomy and life history. Furthermore, neither island remoteness nor island area significantly explained AM fungal diversity. These results indicate that isolation does not perceivably restrict immigration or promote endemism as a result of taxogenesis, in island compared with mainland communities, and suggest that long-distance dispersal might be effective within this group of organisms. Such a pattern deviates considerably from those typically recorded among macroscopic organisms [4]. Nonetheless, we found that compositional distances between AM fungal communities on islands and paired mainland sites exceeded those observed between mainland sites of equivalent geographic separation. Furthermore, island remoteness was associated with certain taxonomic and life history characteristics that provide clues about AM fungal dispersal and establishment on distant islands.

Few endemic taxa among island AM fungal communities

Some case studies have identified previously unrecorded AM fungal phylogroups or morphospecies from island systems [56, 57]. Measuring endemism is, however, contingent on the availability of comparative global data, while interpretation is also shaped by the taxonomic resolution of observations ([58]; see the Supplementary Methods for a discussion of VT resolution). Using the most comprehensive available comparative data set, we discovered six previously unrecorded AM fungal VT in this analysis, but only one was endemic to a single island (present at both sites on Tikehau, an atoll in French Polynesia in the South Pacific Ocean). Furthermore, all taxa that were recorded from a single island site in this analysis had previously been reported from mainland or other island locations (as indicated by their presence in the MaarjAM database). Our sampling approach may have overlooked endemic taxa in unsampled areas of study islands or indeed in sampling plots, if the taxa were present at low abundance. Nonetheless, the apparent lack of endemism in island communities—even large or isolated island communities—strongly suggests that the contribution to island diversity of in situ taxogenesis (at the level of VT) is low compared with that of immigration. Furthermore, the fact that taxonomic diversity was similar at island and mainland sites indicates that strong immigration is not significantly outweighed by local extinctions on islands.

Our inference that long distance dispersal of AM fungal VT is relatively efficient, compared with that of many animal and plant species, is not entirely unexpected. A global survey of mainland AM fungal communities indicated that many AM fungal VT have distribution areas encompassing multiple continents, with VT lists exhibiting low turnover at large spatial scales [13]. Furthermore, recent genetic evidence has shown that individual genotypes within the Rhizophagus irregularis species group are present on multiple continents [20]. The diversity and composition of local AM fungal communities on distant oceanic islands presented in this study suggest that the wide distribution of AM fungal VT cannot be explained solely by incremental small-scale dispersal events (i.e., in soil). Rather, long-distance dispersal must explain AM fungal presence on islands, and the apparent magnitude of immigration relative to taxogenesis and local extinction suggests that dispersal is relatively efficient rather than occasional.

Island remoteness favours certain life history characteristics

AM fungal communities on distant islands were characterised by relatively high phylogenetic diversity and comprised relatively more spore-forming cultured taxa and taxa from outside of the order Glomerales, even once the environmental characteristics of islands were accounted for. We also found that islands generally harboured somewhat less-well distributed taxa (in terms of the total number of sites occupied) compared with mainland sites, suggesting that the traits allowing taxa to establish on islands do not confer a generally widespread distribution. Furthermore, among cultured taxa, we recorded relatively more large-spored AM fungal taxa on distant islands. On one hand, a predominance of large-spored taxa may indicate that the germination and establishment phases are critical stages in the survival of AM fungal spores reaching distant islands, irrespective of the mode of dispersal. There is some evidence that large-spored fungi are characterised by high germinability and establishment [40] and predominate under resource limitation [33], but information about the significance of spore size for AM fungal establishment is limited [59]. Also, it is unclear why the harshness of the local environment should increase with island remoteness. However, in support of this interpretation, the effect of island remoteness on mean spore diameter was apparent in the IB model but not in the IBE model, where measured environmental variables were accounted for. On the other hand, large spores may indicate that conditions during the dispersal process require a high degree of stress tolerance. In the context of dispersal to distant oceanic islands, transport by seawater appears a plausible dispersal mechanism, as AM fungal spores maintain germinability after storage in seawater [60], though they vary in their tolerance of salinity [61]. Among plants, larger diaspores tend to be better able to survive transport in seawater [46]. Analysis of seawater currents suggests that microbial propagules might take less than 10 years to be transported between any two oceanic locations globally [62]. Such a timescale suggests that transport in seawater is a process potentially capable of producing the cosmopolitan patterns observed in this organism group, while at the same time highlighting the potential benefit of a stress tolerant dispersal strategy. Though AM fungal sequences have been detected from ocean water [63], direct empirical evidence with respect to transport of fungal spores in seawater is lacking.

An alternative explanation for the high diversity of island AM fungal communities and for some of the characteristics exhibited by AM fungal communities on distant islands is that they reflect the role of human-mediated transport. Human activities are believed to have transported some AM fungi over long distances [64]. Although the actual means and rates of human-mediated dispersal are not known, humans may preferentially facilitate dispersal of cultured taxa, simply because these occur disproportionately in disturbed systems, including agricultural settings [37], and produce relatively abundant propagules. Though not directly recorded, human transport is believed to have led highly similar genetic lineages of another soil organism group, Collembola, to occur on several continental landmasses and remote islands worldwide [65].

We recorded relatively more non-Glomerales taxa and greater phylogenetic diversity on distant islands. Case studies have suggested that disturbed habitats tend to be characterised by a relatively low proportion of Glomeraceae [66], which may again reflect favouring of stress tolerance. However, these results and evidence from elsewhere [23, 43, 67] demonstrate that trait–environment relationships must be considered in light of the phylogenetic conservatism in traits considered for analysis. In this analysis, cultured VT are more likely to belong to non-Glomerales clades and spore size is also conserved at a lower taxonomic level within the cultured set. Such patterns mean that observed trait–environment relationships might be a proxy for responses attributable to other conserved traits [68].

Area effects may operate at smaller scales

Recorded AM fungal community characteristics did not vary as much in relation to island area as they did in relation to island remoteness. A similarly weak effect of area has been reported at a smaller scale from remnant forest patches in an agricultural landscape [69]. We see multiple reasons why island area was generally not associated with characteristics of AM fungal communities. First, it is possible that our measures of local diversity did not adequately capture particular island biogeographic processes. For instance, a measure of whole-island gamma diversity might be more sensitive to processes (immigration, taxogenesis, extinction) that define island taxon pools, but which are modulated by local conditions in determining the alpha diversity of samples. Second, island area is expected to determine the rate of stochastic local extinction [4]. Our results might therefore indicate that either island diversity is not importantly limited by extinction or that this process operates at a scale below the range of island sizes in our study (e.g., well below 1 km2). A related point to note is that our study incorporated a relatively small number of islands located over a vast area (essentially global). By collecting a geographically widespread set of samples, we were able to conduct a general test of the effects of isolation per se. However, this generality may have come at the expense of some power to detect relationships between diversity and island characteristics (compared with studying multiple islands in a single archipelago). While we accounted for important environmental variables in our analyses, it is to be expected that the variable physical, climatic and biogeographic context of such a widespread set of islands [70] introduces noise into area–diversity and isolation–diversity relationships. For similar reasons, a degree of caution must be exercised when interpreting the relationships we identified, since our explanatory variables (island vs. mainland, island area, island remoteness) could have been confounded with other unmeasured variables.

Covariation in mutualist responses to isolation?

Different AM fungal communities are known to differentially affect plant performance [71, 72], and there is evidence of differences in effect between Glomerales vs. non-Glomerales AM fungal taxa and between taxa characterised as cultured vs. uncultured or large- vs. small-spored [73, 74]. Equally, the presence and density of suitable host plants may limit the establishment of certain AM fungal taxa (passenger hypothesis; [75]). Thus, it is possible that the dispersal characteristics of either symbiont community have shaped the functional attributes of both plant and AM fungal communities on islands. Our results suggest that dispersal limitation of AM fungi to distant islands is likely to be slight overall. So, it is perhaps more plausible that over-representation of ruderal plant species with small propagules (efficient dispersers) has favoured the establishment of ruderal, large-spored (efficient disperser) AM fungal taxa on islands. Nonetheless, if AM fungal taxa represent the more efficient group of dispersers, the early and efficient arrival of ruderal AM fungal taxa to islands may have had an effect on colonising plants in the past (driver hypothesis; [75]).

Conclusion

Our results provide a first indication of the oceanic island biogeographic processes influencing a microbial organism group. The island biogeography of AM fungi is characterised by efficient dispersal outweighing potential effects of endemism and extinction. Nonetheless, we found that remote island AM fungal communities are functionally distinct due to their high phylogenetic diversity and relative predominance of cultured taxa from non-Glomerales clades and those exhibiting relatively large spores. These characteristics suggest that stress tolerance is an important trait that either reflects the origin of colonising taxa (e.g., anthropogenic systems) or facilitates dispersal and establishment in the abiotic and biotic conditions associated with island systems.

References

Darwin C. (1845). Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N. John Murray, UK.

MacArthur RH, Wilson EO. The theory of island biogeography. NJ, USA: Princeton University Press; 1967.

Simberloff DS, Wilson EO. Experimental zoogeography of islands. A two-year record of colonization. Ecology. 1970;51:934–7.

Whittaker RJ, Fernandez-Palacios JM. Island biogeography: ecology, evolution and conservation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Patiño J, Whittaker RJ, Borges PA, Fernández‐Palacios JM, Ah‐Peng C, Araújo MB, et al. A roadmap for island biology: 50 fundamental questions after 50 years of The theory of Island Biogeography. J Biogeogr. 2017. https://doi.org/1mec.14037/jbi.12986.

Santos A, Field R, Ricklefs RE. New directions in island biogeography. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2016;25:751–68.

Andrews JH, Kinkel LL, Berbee FM, Nordheim EV. Fungi, leaves, and the theory of island biogeography. Microb Ecol. 1987;14:277–90.

Mangan SA, Eom AH, Adler GH, Yavitt JB, Herre EA. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi across a fragmented forest in Panama: insular spore communities differ from mainland communities. Oecologia. 2004;141:687–700.

Peay KG, Garbelotto M, Bruns TD. Evidence of dispersal limitation in soil microorganisms: isolation reduces species richness on mycorrhizal tree islands. Ecology. 2010;91:3631–40.

Bell T, Newman JA, Thompson IP, Lilley AK, van der Gast CJ. Bacteria and island biogeography - Response. Science. 2005;309:1998–9.

Tedersoo L, Bahram M, Põlme S, Kõljalg U, Yorou NS, Wijesundera R, et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science. 2014;346:1256688.

Bardgett RD, van der Putten WH. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature. 2014;515:505–11.

Davison J, Moora M, Öpik M, Adholeya A, Ainsaar L, Ba A, et al. Global assessment of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus diversity reveals very low endemism. Science. 2015;349:970–3.

Öpik M, Moora M, Liira J, Zobel M. Composition of root-colonizing arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in different ecosystems around the globe. J Ecol. 2006;94:778–90.

Spatafora JW, Chang Y, Benny GL, Lazarus K, Smith ME, Berbee ML, et al. A phylum-level phylogenetic classification of zygomycete fungi based on genome-scale data. Mycologia. 2016;108:1028–46.

Smith SE, Read DJ. Mycorrhizal symbiosis. NY, USA: Academic Press; 2008.

Dumbrell AJ, Nelson M, Helgason T, Dytham C, Fitter AH. Relative roles of niche and neutral processes in structuring a soil microbial community. ISME J. 2010;4:337–45.

Lekberg Y, Koide RT, Rohr JR, Aldrich-Wolfe L, Morton JB. Role of niche restrictions and dispersal in the composition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. J Ecol. 2007;95:95–105.

Davison J, Moora M, Jairus T, Vasar M, Öpik M, Zobel M. Hierarchical assembly rules in arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungal communities. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;97:63–70.

Savary R, Masclaux FG, Wyss T, Droh G, Cruz Corella J, Machado AP, et al. A population genomics approach shows widespread geographical distribution of cryptic genomic forms of the symbiotic fungus Rhizophagus irregularis. ISME J. 2018;12:17–30.

Egan C, Li DW, Klironomos JN. Detection of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spores in the air across different biomes and ecoregions. Fungal Ecol. 2014;12:26–31.

Gange AC. Translocation of mycorrhizal fungi by earthworms during early succession. Soil Biol Biochem. 1993;25:1021–6.

Lekberg Y, Meadow J, Rohr JR, Redecker D, Zabinski CA. Importance of dispersal and thermal environment for mycorrhizal communities: lessons from Yellowstone National Park. Ecology. 2011;92:1292–302.

Nielsen KB, Kjøller R, Bruun HH, Schnoor TK, Rosendahl S. Colonization of new land by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Fungal Ecol. 2016;20:22–29.

Harner MJ, Opitz N, Geluso K, Tockner K, Rillig MC. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on developing islands within a dynamic river floodplain: an investigation across successional gradients and soil depth. Aquat Sci. 2011;73:35–42.

Jacquet C, Mouillot D, Kulbicki M, Gravel D. Extensions of Island Biogeography Theory predict the scaling of functional trait composition with habitat area and isolation. Ecol Lett. 2017;20:135–46.

Carvajal-Endara S, Hendry AP, Emery NC, Davies TJ. Habitat filtering not dispersal limitation shapes oceanic island floras: species assembly of the Galápagos archipelago. Ecol Lett. 2017;20:495–504.

Adsersen H. Intra-archipelago distribution patterns of vascular plants in Galapagos. Monogr Syst Bot Mo Bot Gard. 1988;32:67–78.

Vargas P, Nogales M, Jaramillo P, Olesen JM, Traveset A, Heleno R. Plant colonization across the Galápagos Islands: success of the sea dispersal syndrome. Bot J Linn Soc. 2014;174:349–58.

Louca S, Parfrey LW, Doebeli M. Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean microbiome. Science. 2016;353:1272–7.

Nelson MB, Martiny AC, Martiny JBH. Global biogeography of microbial nitrogen-cycling traits in soil. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:8033–40.

Green JL, Bohannan BJM, Whitaker RJ. Microbial biogeography: From taxonomy to traits. Science. 2008;320:1039–43.

Halbwachs H, Heilmann-Clausen J, Bässler C. Mean spore size and shape in ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic assemblages show strong responses under resource constraints. Fungal Ecol. 2017;26:59–64.

Andrew C, Heegaard E, Halvorsen R, Martinez-Peña F, Egli S, Kirk PM, et al. Climate impacts on fungal community and trait dynamics. Fungal Ecol. 2016;22:17–25.

Öpik M, Davison J. Uniting species- and community-oriented approaches to understand arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity. Fungal Ecol. 2016;24:106–13.

van der Heijden MG, Bardgett RD, van Straalen NM. The unseen majority: soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol Lett. 2008;11:296–310.

Ohsowski BM, Zaitsoff PD, Öpik M, Hart MM. Where the wild things are: looking for uncultured Glomeromycota. New Phytol. 2014;204:171–9.

Nathan R, Schurr FM, Spiegel O, Steinitz O, Trakhtenbrot A, Tsoar A. Mechanisms of long-distance seed dispersal. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23:638–47.

Norros V, Rannik Ü, Hussein T, Petäjä T, Vesala T, Ovaskainen O. Do small spores disperse further than large spores? Ecology. 2014;95:1612–21.

Norros V, Karhu E, Norden J, Vahatalo AV, Ovaskainen O. Spore sensitivity to sunlight and freezing can restrict dispersal in wood-decay fungi. Ecol Evol. 2015;5:3312–26.

Westoby M, Falster DS, Moles AT, Vesk PA, Wright IJ. Plant ecological strategies: some leading dimensions of variation between species. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 2002;33:125–59.

Bago B, Zipfel W, Williams RM, Chamberland H, Lafontaine JG, Webb WW, et al. In vivo studies on the nuclear behaviour of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Gigaspora rosea grown under axenic conditions. Protoplasma. 1998;203:1–15.

Klironomos JN, Hart MM, Gurney JE, Moutoglis P. Interspecific differences in the tolerance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to freezing and drying. Can J Bot. 2001;79:1161–6.

Varga S, Finozzi C, Vestberg M, Kytoviita MM. Arctic arbuscular mycorrhizal spore community and viability after storage in cold conditions. Mycorrhiza. 2015;25:335–43.

Heleno R, Vargas P. How do islands become green? Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2015;24:518–26.

van der Pijl L. Principles of dispersal in higher plants. Berlin: Springer; 1982.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10.

Öpik M, Vanatoa A, Vanatoa E, Moora M, Davison J, Kalwij JM, et al. The online database MaarjAM reveals global and ecosystem distribution patterns in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota). New Phytol. 2010;188:223–41.

Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1969–73.

Grime JP. Benefits of plant diversity to ecosystems: immediate, filter and founder effects. J Ecol. 1998;86:902–10.

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.3-5. 2016. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

Chao A, Chiu CH, Jost L. Unifying species diversity, phylogenetic diversity, functional diversity, and related similarity and differentiation measures through Hill numbers. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2014;45:297–324.

Kembel SW, Cowan PD, Helmus MR, Cornwell WK, Morlon H, Ackerly DD, et al. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1463–4.

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team. nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1-125. 2016. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48.

Koske R, Gemma JN. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on Hawaiian sand dunes: Island of Kaua’i. Pac Sci. 1996;50:36–45.

Melo CD, Luna S, Krüger C, Walker C, Mendonça D, Fonseca HM, et al. Communities of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi under Picconia azorica in native forests of Azores. Symbiosis. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13199-017-0487-2.

Powell JR, Monaghan MT, Öpik M, Rillig MC. Evolutionary criteria outperform operational approaches in producing ecologically relevant fungal species inventories. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:655–66.

Marleau J, Dalpe Y, St-Arnaud M, Hijri M. Spore development and nuclear inheritance in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:51.

Koske R, Bonin C, Kelly J, Martinez C. Effects of sea water on spore germination of sand-dune-inhabiting arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. Mycologia. 1996;88:947–50.

Juniper S, Abbott LK. Soil salinity delays germination and limits growth of hyphae from propagules of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza. 2006;16:371–9.

Jönsson BF, Watson JR. The timescales of global surface-ocean connectivity. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11239.

Li W, Wang M, Pan H, Burgaud G, Liang S, Guo J, et al. Highlighting patterns of fungal diversity and composition shaped by ocean currents using the East China Sea as a model. Mol Ecol. 2018;27:564 https://doi.org/1mec.14037/mec.14440.

Rosendahl S, Mcgee P, Morton JB. Lack of global population genetic differentiation in the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus mosseae suggests a recent range expansion which may have coincided with the spread of agriculture. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:4316–29.

Cicconardi F, Borges PA, Strasberg D, Oromí P, López H, Pérez‐Delgado AJ, et al. MtDNA metagenomics reveals large‐scale invasion of belowground arthropod communities by introduced species. Mol Ecol. 2017;26:3104 https://doi.org/1mec.14037/mec.14037.

Moora M, Davison J, Öpik M, Metsis M, Saks Ü, Jairus T, et al. Anthropogenic land use shapes the composition and phylogenetic structure of soil arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2014;90:609–21.

Veresoglou SD, Caruso T, Rillig MC. Modelling the environmental and soil factors that shape the niches of two common arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal families. Plant Soil. 2013;368:507–18.

de Bello F, Berg MP, Dias AT, Diniz-Filho JAF, Götzenberger L, Hortal J, et al. On the need for phylogenetic ‘corrections’ in functional trait-based approaches. Folia Geobot. 2015;50:349–57.

Grilli G, Urcelay C, Galetto L, Davison J, Vasar M, Saks Ü, et al. The composition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in the roots of a ruderal forb is not related to the forest fragmentation process. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:2709–20.

Weigelt P, Jetz W, Kreft H. Bioclimatic and physical characterization of the world’s islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:15307–12.

Uibopuu A, Moora M, Öpik M, Zobel M. Temperate forest understorey species performance is altered by local arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities from stands of different successional stages. Plant Soil. 2012;356:331–9.

Williams A, Ridgway HJ, Norton DA. Growth and competitiveness of the New Zealand tree species Podocarpus cunninghamii is reduced by ex-agricultural AMF but enhanced by forest AMF. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43:339–45.

Hoeksema JD, Chaudhary VB, Gehring CA, Johnson NC, Karst J, Koide RT, et al. A meta-analysis of context-dependency in plant response to inoculation with mycorrhizal fungi. Ecol Lett. 2010;13:394–407.

Koch AM, Antunes PM, Maherali H, Hart MM, Klironomos JN. Evolutionary asymmetry in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: conservatism in fungal morphology does not predict host plant growth. New Phytol. 2017;214:1330–7. https://doi.org/1mec.14037/nph.14465.

Hart MM, Reader RJ, Klironomos JN. Life-history strategies of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in relation to their successional dynamics. Mycologia. 2001;93:1186–94.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Andres Koppel, Hendrik Moora, Jodi Price, Riin Tamme and Anna Zobel for help with fieldwork. We are grateful to José María Fernández-Palacios for commenting on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Estonian Research Council (IUT 20-28, IUT 20-29, PUT1170, PUTJD78), the European Regional Development Fund (Centre of Excellence EcolChange) and GIP CNRT (GIPCNRT98).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davison, J., Moora, M., Öpik, M. et al. Microbial island biogeography: isolation shapes the life history characteristics but not diversity of root-symbiotic fungal communities. ISME J 12, 2211–2224 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0196-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0196-8

This article is cited by

-

A genus in the bacterial phylum Aquificota appears to be endemic to Aotearoa-New Zealand

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Species diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal but not ectomycorrhizal plants decreases with habitat loss due to environmental filtering

Plant and Soil (2023)

-

Mycorrhizal types influence island biogeography of plants

Communications Biology (2021)

-

Uncovering multi-faceted taxonomic and functional diversity of soil bacteriomes in tropical Southeast Asian countries

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Dispersal of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi: Evidence and Insights for Ecological Studies

Microbial Ecology (2021)