Abstract

Global trade increases plant introductions, but joint introduction of associated microbes is overlooked. We analyzed the ectomycorrhizal fungi of a Caribbean beach tree, seagrape (Coccoloba uvifera, Polygonacaeae), introduced pantropically to stabilize coastal soils and produce edible fruits. Seagrape displays a limited symbiont diversity in the Caribbean. In five regions of introduction (Brazil, Japan, Malaysia, Réunion and Senegal), molecular barcoding showed that seagrape mostly or exclusively associates with Scleroderma species (Basidiomycota) that were hitherto only known from Caribbean seagrape stands. An unknown Scleroderma species dominates in Brazil, Japan and Malaysia, while Scleroderma bermudense exclusively occurs in Réunion and Senegal. Population genetics analysis of S. bermudense did not detect any demographic bottleneck associated with a possible founder effect, but fungal populations from regions where seagrape is introduced are little differentiated from the Caribbean ones, separated by thousands of kilometers, consistently with relatively recent introduction. Moreover, dry seagrape fruits carry Scleroderma spores, probably because, when drying on beach sand, they aggregate spores from the spore bank accumulated by semi-hypogeous Scleroderma sporocarps. Aggregated spores inoculate seedlings, and their abundance may limit the founder effect after seagrape introduction. This rare pseudo-vertical transmission of mycorrhizal fungi likely contributed to efficient and repeated seagrape/Scleroderma co-introductions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global trade increases plant introductions, and thereby the emergence of invasive exotic plant species [1, 2], some of which drastically modify ecosystem dynamics and services [3, 4]. Beyond introduction of plants, microbes hitchhike on plant movements [5,6,7]. Such co-introductions also modify ecosystems, because parasites can spread [5, 8], and because mutualist microbes reinforce invasive abilities of their host [9, 10]. Better understanding of how microbes accompany plant introductions is thus required. However, microbial co-introductions have been documented in a limited number of model plants, mostly invasive or planted on a large scale, and mostly from temperate regions [7, 11]. Conversely, we lack microbial data on non-invasive introductions, especially in the tropics.

Mycorrhizal fungi are vital for plant nutrition and survival [12]. Some mycorrhizal fungi were deliberately introduced for management purposes [11, 13, 14], but also have spread unintentionally [15]. Introduction of mycorrhizal fungi can entail unwanted effects, such as emergence of toxic species in new places [16], enhancement of host invasiveness [17, 18] and modification of fungal communities [19, 20]. Three scenarios are documented for mycorrhizal fungi of introduced plants [9, 21]: co-introduction (and sometimes co-invasion), cosmopolitan mutualisms and new mutualisms. The ‘co-introduction’ of fungal symbionts from the host native range is especially required when the host needs fungi absent from sites of introduction, as documented for ectomycorrhizal (ECM) trees in regions devoid of ECM fungi, for example, Pinus out of the Northern Hemisphere [17, 18], or Alnus and Salix in New Zealand [22]. Whenever similar fungi exist in both native and introduction ranges, they allow ‘cosmopolitan mutualisms’, that is, association with symbionts existing over both ranges, as commonly observed for plants mycorrhizal with Glomeromycota [23]. Finally, introduced plants can also form ‘new mutualisms’ with members of local fungal communities, as documented for Eucalyptus in the Seychelles [24] and in Zambia [25], or Pinus in Iran [26]. A combination of co-introductions and new mutualisms has often been observed, for example, for Pseudotsuga menziesii in New Zealand [27] and France [14], Pinus species in Argentina [17], and Eucalyptus species in Iberia [28] and Africa [25, 29]. Although non-specificity dominates in mycorrhizal associations [12], some preference may thus exist for fungi from the native range. However, when considering specific vs. generalist mycorrhizal fungi (i.e., narrow vs. broad host range), both types display a similar predisposition to introduction [15]. This has never been addressed with regard to specific plant: what happens after introduction of plants displaying mycorrhizal specificity in their regions of origin (ROs)? We postulate that such specificity drives co-introduction, with limited or no new mutualisms.

We document here a case study of an introduced, non-invasive plant displaying mycorrhizal specificity, namely seagrape (Coccoloba uvifera), a Caribbean Polygonacaeae introduced pantropically. The neotropical genus Coccoloba displays low ECM fungal diversity [30, 31], likely due to the recent emergence of the ECM symbiosis in this genus [32]. Seagrape is a tree natively growing on Caribbean sandy seashores [33], where associates with few ECM fungal taxa (from 1 to 25 species, from 1 to 6 families, depending on populations; [30, 32]). These specific associations enhance growth and salt tolerance [34] and are probably selected by soil drought and salinity [32]. Seagrape generated interest because it stabilizes sandy or salty soils, and because it produces fruits with a fleshy edible pericarp. Seagrape has been planted pantropically from dry, single-seeded fruits, although details on times and origins of introductions are lacking [35]. Seagrape offers replicates of non-invasive introductions to test for the co-introduction potential in species with specific mycorrhizal partners.

In this study, we sampled five globally distributed regions of introduction (RIs), and revealed by fungal barcoding that seagrape in RIs nearly exclusively associates with two Scleroderma species (Basidiomycota; [36]). We then explored the geographic origin of one Scleroderma species by investigating its genetic diversity in RIs vs. Caribbean ROs of seagrape. Assuming co-introduction, we expected a founder effect in RIs and incongruences between patterns of genetic isolation by distance at the global level vs. within ROs. Further investigating mechanisms for co-introduction, we tested the possibility that fruits transmit Scleroderma spores to explain the worldwide association of Scleroderma spp. and seagrape.

Materials and methods

Fungal barcoding

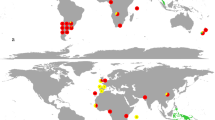

Seagrape ECM fungi were identified from five RIs, where native ECM fungi either exist on other hosts (Senegal, Japan and Malaysia) or not (Brazil and Réunion; Table S1). In each region, we investigated one to four sites (Table S1; Fig. 1). We sampled 9–14 soil cores (15-cm diameter and 20-cm depth) per site under adult seagrapes. For each core, 8–45 ectomycorrhizae were randomly excised and barcoded using internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of the nuclear ribosomal DNA as in Séne et al. [32]. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were defined for sequences sharing at least 97% pairwise similarity, and representative sequences were deposited in GenBank (Table S2). Scleroderma ITS sequences were used to build a phylogenetic hypothesis for this genus (see Fig. S1 for details).

Ectomycorrhizal communities in one region of origin of seagrape (Guadeloupe, after Séne et al. [30]) and sites from five regions of introduction, in percent of barcoded ectomycorrhizae. For each site, the numbers in brackets indicate the sampling effort, respectively, the number of soil cores and total number of ectomycorrhizae investigated. The diverse OTUs found in Guadeloupe are detailed in Table S2; Thelephora sp. #1 occurs in both Guadeloupe and Brazil

Mycorrhizal baiting experiments under adult trees in RI

Sterile seedlings of seagrapes and Eucalyptus camaldulensis (an ECM Myrtaceae introduced in Senegal that coexists with seagrape; [29]) were pre-grown in the greenhouse at Laboratoire Commun de Microbiologie (LCM, Dakar, Senegal), away from any S. bermudense spore source. Seeds were surface sterilized: for seagrape, remnants of pericarp were trimmed before fruit incubation for 90 min in H2SO4 (95%) due to the woody endocarp, while E. camaldulensis seeds were incubated for 90 min in sodium hypochlorite (9% v/v). Seeds were sown in individual pots filled with beach soil sterilized by heating at 200 °C for 2 h. Soil was protected from ambient air by aluminum sheets and watered daily with sterile water. After 1 month, a subset of 10% of seedlings was checked for the absence of ectomycorrhizae and the remaining seedlings were transplanted for two experiments. For a first in situ experiment, three adult seagrapes and three adult E. camaldulensis growing on sandy soil at Mbour (Senegal; see Table S1) each received five seagrape seedlings and five E. camaldulensis seedlings. For a second ex situ experiment, soils were sampled under three adult trees of each species from three sites in Senegal (Mbour, Gandiol and Dakar; Table S1). Soils from same tree species and site were pooled, resulting in six soil pools (Table S3) at the LCM greenhouse. Sterile seedlings of seagrape or E. camaldulensis were transplanted in individual pots filled with the non-sterile soil pools (n = 5 seedlings per species and soil pool).

In each experiment, 6 months after transplant, five ectomycorrhizae were randomly sampled from five different seedlings per treatment (in total, 25 samples for each of the six treatments and two species in each experiment). Fungi were identified in three steps: first, ectomycorrhizae were sorted by morphotype; second, homogeneity of ITS sequence in each morphotype was ensured by restriction fragment length polymorphism using the enzymes MspI and HaeIII as in Richard et al. [37]; finally, up to 10 representatives per morphotype were barcoded as above to ensure homogeneity for ITS (except for morphotypes found <3 times, classified as ‘others’).

Scleroderma bermudense population genetics

We investigated S. bermudense populations under seagrape in three RIs (French Guiana, Senegal and Réunion) and three ROs (Guadeloupe, Martinique and Puerto Rico), sampling 1–5 sites per region (Table 1 and S1). We re-used S. bermudense ectomycorrhizae obtained in Guadeloupe by Séne et al. [32], and sampled ectomycorrhizae and/or sporophores from other regions (Table S1). Sporophores were sampled in the French Guiana site, an introduced seagrape plantation (Howard 1961; our personal observations) with roots exclusively colonized by S. bermudense [30]. For ectomycorrhizae, we randomly selected one sample per core to avoid repetitive sampling of the same genet. DNA was extracted as above and submitted to microsatellite analysis using six polymorphic loci designed for this study (see Table S4 for methods). Allelic richness, FST values and Mantel test for isolation by distance were investigated using Genepop 4.4 [38]. To test for recent bottlenecks in each population, the M-ratio (ratio of the number of microsatellite alleles to the range of allele size due to repetition polymorphism) was calculated as in Garza and Williamson [39]. Genetic structure among populations was analyzed using STRUCTURE 2.2 [40] without prior knowledge of sample origin, with number of potential clusters from K = 1 to 18 (5 independent runs of 100,000 simulations after a burn-in of 10,000 simulations); we tested four possible a priori parameter combinations (ancestry model with or without admixture; allelic frequencies correlated or independent). STRUCTURE 2.2 was used with similar simulation parameters for assignment tests, which were conducted on samples from RI (Senegal, Reunion, French Guiana) with option Usepopinfo, where prior geographic information was given for RO samples used as learning samples. In order to estimate the proportion of genetic variance explained by geographic regions, or by RO and RI, analyses of molecular variance (AMOVA) were run in Arlequin 3.5 ([41]; standard AMOVA, 1000 repetitions).

Microscopic observation of seagrape fruits

Dry seagrape fruits were collected under trees in Guadeloupe (Bois-Jolan, Cluny and Viard) and Martinique (Diamant and Carbet; Table S1) in August 2013 and isolated from each other in sterile bags (n = 10 fruits per site; Table S1). The presence of S. bermudense spores was checked on fruit trimmings by light microscopy, and one densely colonized fruit per site was submitted to scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Pericarp trimmings were fixed for 2 h at 4 °C in 2% glutaraldehyde solution in cacodylate buffer (900 mM, pH 7.2), then dehydrated in graded concentrations of acetone, critical point-dried in CO2, and finally sputter-coated with gold (using a sputter coater; Bio-Rad Microscience Division). Observations were made with a Quanta 250 SEM (trademark FEI), fitted with a tungsten filament, running at 10 kV in High Vac mode (6.10−4 Pa). Secondary electron images were acquired with an Everhart-Thornley detector. To confirm the presence of S. bermudense, trimmings from the fruits were barcoded as above with the basidiomycete-specific primers ITS4B-ITS1F (as in Séne et al. [32]).

Axenic germination of seagrape

The potential of seagrape fruits to inoculate S. bermudense onto seedlings was investigated on fruits sampled in August 2013 from the three Guadeloupe beach sites above. Soil from each site was collected and sterilized as above. Fruits, either non-sterile or sterilized as above, were sown in 1 kg of their respective sterilized soils in the LCM greenhouse in September 2013. To ensure ECM abilities of seedlings after fruit surface sterilization, we supplemented additional sterilized fruits with either unsterile trimmings from three other fruits each or 0.5 g of dried S. bermudense spores for Bois-Jolan only (trimmings and spores from the same origin as fruits). For each origin, 10 replicate sowings were done for each of the four treatments (control = non-sterilized; sterilized; sterilized with trimmings; sterilized with spores), protected from air by aluminum sheets. After 6 months, we evaluated the percentage of root tips with ectomycorrhizae. Five ectomycorrhizae from five seedlings per treatment were analyzed as for the baiting experiments above.

Results

Scleroderma spp. dominate inRIs of seagrape

Fungal ECM communities were investigated in five RIs (Brazil, Japan, Malaysia, Réunion and Senegal), from 105 soil cores and 1688 ectomycorrhizae in all. They were dominated by two Scleroderma OTUs (Fig. 1). Three other OTUs were found, namely one Entolomataceae and two Thelephoraceae, one of which was known from RO (Thelephora sp. #1; [32]). Non-Scleroderma ectomycorrhizae occurred in one core per RI only, except Thelephora sp. #1 (4 cores in Malaysia). In Senegal and Réunion, S. bermudense was the exclusive partner, with a monomorphic ITS sequence (KJ209670). In Brazil, Japan and Malaysia, Scleroderma sp. #1 dominated with two closely related ITS sequences differing by an indel (KX573919-20) and diverging from S. bermudense by 8.1% and 9.6%, respectively. Scleroderma sp. #1 is referred as ‘SH192839.06FU’ in the UNITE database [42] and is already known from RO Caribbean sites [30]. In an ITS phylogeny of the genus Scleroderma, Scleroderma sp. #1 clusters with S. bermudense and an unknown Caribbean Scleroderma species with 0.97 bootstrap support (Fig. S1).

Introduced seagrape seedlings preferentially associate with S. bermudense

To test whether the low ECM diversity on seagrape in RIs was due to a restricted access to local ECM fungi, seedlings of seagrape and Eucalyptus camaldulensis were grown in Senegal under adult trees of each species. Under E. camaldulensis adults, conspecific seedlings were colonized by several ECM fungi including Scleroderma bovista, but no S. bermudense, whereas seagrape seedlings were exclusively colonized by S. bermudense (Table 1). Conversely, under seagrape adults, E. camaldulensis seedlings were not mycorrhizal, whereas seagrape seedlings were exclusively colonized by S. bermudense (Table 1). Similar baiting results were observed in the greenhouse, using soils from three Senegal sites (Table S3). Thus, the fungal community of E. camaldulensis offered no symbiont suitable for seagrape seedlings, whereas seagrape and S. bermudense showed a reciprocal preference in all soils.

Evidence for co-introduction of S. bermudense with seagrape

To elucidate whether S. bermudense is indigenous in RIs or introduced from ROs, we genotyped 410 samples from three RIs (French Guiana, Senegal and Réunion) and three ROs (Guadeloupe, Martinique and Puerto Rico; Table 2 and S4). Allelic richness did not differ among regions, whereas private alleles occurred only in Puerto Rico (Table 2), even after rarefaction analysis (data not shown). Puerto Rico may thus be closer to the center of genetic diversity of S. bermudense. Nei’s diversities, which account for sampling effort, tended to be slightly higher in ROs than in RIs (Table 2), but values overlapped. M-ratios (which are expected to decline after a bottleneck; Table 2) were all below the 0.68 threshold proposed by Garza and Williamson [39] for stable populations, and RIs tended to have slightly lower M-ratios. This result, along with other tests for population size reduction (Table S6), suggested that founder effects in RIs were similar or only slightly more pronounced, as compared with ROs.

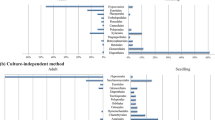

Mantel tests revealed significant isolation by distance in ROs (i.e., in the Caribbean; P = 0.007; R2 = 0.304), but strikingly not at the global scale (P = 0.996; Table S5; Fig. 2a). Compared with extrapolation of the trend observed among RO populations (dotted line on Fig. 2a), populations from RIs were poorly genetically differentiated from the RO ones, and between them (see, e.g., Senegal and Réunion). Accordingly, AMOVAs showed that the variance is explained by regions, sites and within-sites diversity, but not by RI vs. RO (Table 3). Cluster analysis with STRUCTURE revealed, whatever the prerequisites of the ancestry model and allelic frequencies, two genetic clusters as the most likely scenario (Fig. 2b): one cluster encompassed Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana and Senegal, and the second Réunion and Puerto Rico (Fig. 2b). Finally, in assignment tests of individuals from RIs to the RO metapopulation (Guadeloupe, Martinique and Puerto Rico), 97.1% of RI individuals were assigned to RO with a >0.95 probability. Thus, RIs and ROs populations showed genetic similarities not explained by geography.

Global genetic structure of S. bermudense populations. a Isolation by distance among S. bermudense populations in regions of origin of seagrape (ROs, i.e., considering pairs of populations from Caribbean sites; pairs in red) and at global scale (i.e., all population pairs including sites from the regions of introduction, RIs). Pairs are colored according to the sites considered (see panel legend); due to overlap, several pairs may be represented by a single dot. b Cluster analysis of S. bermudense populations, based on the software STRUCTURE 2.2 for two clusters, the most likely scenario retrieved. All 410 samples are represented on the abscissa, with their geographic origin; on the ordinate, estimated membership probability (Q) to cluster #1 (in red) or cluster #2 (in green) for each sample

Scleroderma bermudense inoculant spores are transported on seagrape fruits

Seagrape fruits contain a single seed surrounded by a fleshy pericarp (Fig. 3a) that fall and dry on sand (Fig. 3b) where old Scleroderma sporocarps deliver spores (Figs. 3c, d). To understand how S. bermudense efficiently colonizes seagrape populations, we looked for S. bermudense spores on dried fruits from five Caribbean sites (Table S1). Under light microscopy, 4 to 8 (5.6 ± 1.5, out of 10) fruits per site showed Scleroderma spores on the pericarp, and this was confirmed by SEM (Figs. 3e, f). Finally, PCR amplification of DNA extracted from pericarp trimmings with the basidiomycete-specific primers ITS1F-ITS4B detected S. bermudense in 16 fruits (out of 50; 0 to 6 fruits per site; 3.2 ± 2.6).

Seagrape fruits and S. bermudense spores from Bois-Jolan (Guadeloupe). a Fresh and b dry seagrape fruit; c S. bermudense sporocarps, either semi-hypogeous and immature (red asterisks), or old and releasing spores (arrowheads), with a section of a young sporocarp displaying the violet immature spore mass; d S. bermudense spores in light microscopy; e, f TEM of pericarp surface from a fruit covered by Scleroderma spores (arrowheads). Bars are 1 cm in a-c; 10 µm in d-f

Spores carried by seagrape fruits can inoculate seedlings

To test for the inoculum potential of spores adhering to the pericarp, we sowed fruits from three Guadeloupe sites (Fig. 4) on sterilized beach sand. After 6 months, seedlings from non-sterilized fruits were scarcely (at Bois-Jolan and Cluny) to highly (Viard) colonized by a single ECM morphotype identical in morphology and ITS to S. bermudense. Seedlings from surface-sterilized fruits were non-mycorrhizal, except one seedling with 2 out of 5 sampled roots colonized by Pyronemataceae sp. #1 (KJ690091). This suggested that pericarp spores inoculated S. bermudense in non-sterilized treatments. Seedlings from sterilized fruits supplemented with either pericarp trimmings or S. bermudense spores were ECM with S. bermudense (Fig. 4; in addition, two Cluny seedlings were colonized by Pyronemataceae sp. #1 on, respectively, 1 and 2 out of 5 roots sampled). Despite one Pyronemataceae contaminant, we conclude that S. bermudense spores adhering to the pericarp can inoculate seagrape seedlings.

Mycorrhizal colonization (% of apex colonized) by S. bermudense of 6-month-old seagrape seedlings from Bois-Jolan, Cluny and Viard, sown on their respective sterilized beach sand. Treatments: control = non-sterilized fruits (dotted column), surface-sterilized fruits (gray; always 0%), surface-sterilized fruits inoculated by non-sterile fruit trimmings from the same origin (white), and surface-sterilized fruits inoculated by S. bermudense spores (black, for Bois-Jolan only). See main text for ECM contaminants observed in a few seedlings (not presented here). Bars correspond to standard deviations (n = 10 seedlings per treatment) and for each site, different letters indicate a significant difference according to ANOVA (P < 0.0001). 0, no S. bermudense ectomycorrhizae found

Discussion

During its pantropical introduction, seagrape lost most of its Caribbean ECM fungal diversity, and mostly associated with two phylogenetically close Scleroderma species in RIs. An unknown Scleroderma in Brazil, Malaysia and Japan, and S. bermudense in Réunion and Senegal colonized 96.7% of investigated ectomycorrhizae. Seagrape seedlings in Senegal did not associate with locally available ECM fungi. We discuss these results taking into account (1) the attachment of Scleroderma spores on seagrape fruits, and (2) the genetic diversity of S. bermudense in RIs.

Scleroderma spp. dominate inRIs

Diversity indices for ECM fungi in Caribbean seagrape forests are among the smallest for monospecific ECM forests ([30, 31]; [43]. Yet, this diversity is even lower in RIs, with up to two taxa per region, despite a higher sampling effort than in the ROs. The two dominant Scleroderma species found in RIs also abound, and sometimes even dominate, under seagrape in ROs [30, 32]. They can even coexist in ROs ([30]; our unpublished study at Pastillo Middles (Puerto Rico) detected Scleroderma sp. #1 and S. bermudense in a 1:9 ratio on 151 ectomycorrhizae). In RIs, however, these two Scleroderma species never occur sympatrically. Põlme et al. [30] investigated the seagrape ECM community in the RI site from French Guiana that we investigated here for population genetics, and recovered exclusively S. bermudense. Thus, Scleroderma species exclusively dominate in RIs, even close to ROs.

Scleroderma spp. dominated even in RIs where native ECM fungi occur (i.e., Japan, Malaysia and Senegal). In Senegal, seagrape seedlings do not associate with ECM fungi from E. camaldulensis, although this tree harbors diverse ECM fungi [29]. Thus, the depauperate ECM community in RIs potentially results from a trend to ECM specificity, in addition to the founder effect of limited ECM co-introductions. A long coevolution with few fungal partners in extreme soil conditions [44] may have reinforced seagrape preference for a few fungal lineages. Põlme et al. [30] suggested a similar coevolution for Thelephora species that dominate ROs communities, and indeed we found Thelephora spp. in two sites of RIs.

The inability of S. bermudense to colonize E. camaldulensis seedlings suggests a reciprocal specificity. The genus Scleroderma has variable ECM specificity [36], and includes a subclade specific to ECM Gnetum (Gnetopsida), which is highly frequent or even dominant on Gnetum roots [45, 46]. Scleroderma sp. #1 and S. bermudense themselves belong to a Caribbean subclade within Scleroderma that may similarly have evolved specificity to seagrape and its particular soil conditions. An ancient evolutionary and ecological link would also explain the protective effect against salt described for S. bermudense on seagrape [34, 44].

Pseudo-vertical transmission of Scleroderma bermudense

Symbioses undergo two modes of transmission [47]. In vertical transmission, at least one parent provides symbionts to the next generation, whereas in horizontal transmission, different symbionts reassemble at each generation. Horizontal transmission is the rule for root symbionts, perhaps because they are too far from seeds to evolve vertical transmission. Yet, in some formally horizontal transmissions, the symbionts acquired are actually those from the parents that live in the neighborhood. In mycorrhizal symbioses, such a ‘pseudo-vertical’ transmission occurs when seeds germinate close to the maternal plant [48, 49]. Here, we describe a novel mechanism of pseudo-vertical transmission.

This pseudo-vertical transmission requires (i) the fleshy pericarp of seagrape that aggregates dust while drying on soil, and (ii) the dense spore bank produced by S. bermudense. Dense spore banks characterize fungi producing (semi-)hypogeous sporocarps filled with thick-walled spores, some of which remain undispersed [50, 51]. In an additional experiment, we tested the inoculum potential of this spore bank by adding soil from seagrape beach sites on seedlings germinated axenically: this resulted in 13–56% ECM roots colonized by S. bermudense (Fig. S2). Thus, the spore bank and fleshy fruits favor a pseudo-vertical transmission. Whether spore adhesion resists dispersal by sea water (which is common for seagrape) remains to be demonstrated, but it is relevant for local propagation on a beach and for anthropic dispersal of fruits.

Vertical transmission selects for mutualism [52, 53], because any cheater harming its symbiont will produce offspring interacting with partners of lower quality, while any better altruist will provide improved partners to its offspring. In the seagrape-Scleroderma interaction, the spore bank is likely genetically close to established mycelia, due to limited dispersal, as in other (semi-)hypogeous fungi [50, 51]. Thus, fruits tend to associate with spores genetically close to mycelia colonizing mother trees, and maintaining similar genetic combinations over Scleroderma/seagrape generations. This may have selected for increasing mutualism, including specificity, growth enhancement and protection against salt [34].

Pseudo-vertical transmission in mycorrhizal symbiosis deserves investigation in other plants with fleshy fruits, and beyond. Indeed, spores were recently found on dry seeds of a Southern Asian Dipterocarpaceae tree, Shorea leprosula, inoculating Thelephoraceae and, interestingly, Scleroderma spp. on seedlings [54]. The seagrape-Scleroderma pseudo-vertical transmission may explain (i) the abundance of Scleroderma in all seagrape ECM communities [30], and (ii) why other taxa mycorrhizal associated with seagrape in ROs scarcely ever colonize seagrape in RIs.

A co-introduction of seagrape and S. bermudense ?

Are Scleroderma spp. in RIs introduced or locally recruited? We can only comment on genetic data available for S. bermudense. On the one hand, this species is considered as Caribbean [36]. Indeed, to our best knowledge, it was only reported under seagrape, and private alleles occurred only in Puerto Rico. On the other hand, S. bermudense could be a hitherto overlooked pantropical species, becoming conspicuous after seagrape introduction, which could explain the absence of founder effect in RIs.

Although genetic isolation by distance exists in ROs, as expected for ECM fungi (especially hypogeous or semi-hypogeous; [51]), this pattern is disrupted at a global level, with RI populations less differentiated from ROs (and between them) than expected by considering their distance. The loss of genetic geographic structure is expected after anthropic dispersal, whose geopolitical and economic logic escapes the limitations of spore dispersal (e.g., Rivera et al. [13]). High mutation rates at microsatellite loci [55] or non-equilibrium patterns of population expansion [56] can explain the absence of isolation by distance between anciently diverged populations, which could be expected if S. bermudense was anciently pantropical. However, the strong genetic similarities between Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana and Senegal, on one hand, and Réunion and Puerto Rico, on the other hand, may recapitulate introduction patterns. Moreover, a founder effect is reduced if each fruit introduces several S. bermudense spores, and aggregate many genotypes from the beach spore bank: indeed, microsatellite amplifications from fruit trimmings revealed several alleles (data not shown). Thus, our data favor at least two separate introductions of S. bermudense in Africa, and one in French Guiana. Considering Thelephora spp. found in RIs, we cannot exclude that they pre-existed in these regions. However, Thelephora have a potential to be dispersed on ECM hosts’ seeds [54]. Thelephora #2, very abundant on Malaysian seagrapes, is known from Guadeloupe [32], may thus be another co-introduction of a specific symbiont.

Two hypotheses can explain why the two Scleroderma species never co-occur in the RIs, assuming that they share a common Caribbean origin. First, drift may have occurred, leading to the random loss of one species. However, the absence of intraspecific genetic drift for S. bermudense argues against efficient drift during seagrape introduction. Second, Scleroderma sp. #1 and S. bermudense can exclusively dominate in some RO populations ([30]; e.g., Scleroderma sp. #1 exclusively dominates in Colombia), so that different seagrape origins can introduce a different Scleroderma species. As all investigated RIs harboring S. bermudense are French speaking, exchanges between former French colonies may have disseminated S. bermudense that dominates in French Caribbean islands [32].

Conclusions

Anthropic dispersal of seagrape drastically reduced its associated ECM fungal community. The scenario of co-introductions of ECM fungi is supported by (1) the fact that one Thelephora and all Scleroderma spp. found in RIs also occur in ROs of seagrape, and (2) the population genetic structure of S. bermudense. Such plant–fungal co-introductions where new mutualisms are absent or rare, confirms on the plant side, in a non-invasive framework, a pattern reported for specific fungi hitchhiking host invasions, for example, ECM fungi of Pinus [17]. Our results show how introduced horticultural plants can cause hidden fungal introductions, and support our prediction of a high co-introduction potential for species with low diversity of mycorrhizal partners. Seagrape displays two predispositions for co-introduction, namely its specificity (making it irresponsive to local ECM fungi) and its unusual pseudo-vertical transmission of Scleroderma spores aggregating on fruits.

Finally, specific fungi can generate exclusive nursery effects for conspecific seedlings growing under adults [43, 57], because seedlings benefit from fungi already established at the expense of adults. Selectively positive feedback is a common feature in invasive species [58]. Thus, although seagrape is currently non-invasive, careful monitoring of this (and other) mycorrhizal-specific species appears necessary in the long term [60, 61].

References

Boivin N, Petraglia M, Crassard R. Human dispersal and species movement. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

Bradley BA, Blumenthal DM, Early R, Grosholz ED, Lawler JJ, Miller LP, et al. Global change, global trade, and the next wave of plant invasions. Front Ecol Env. 2012;10:20–28.

Simberloff D, Martin JL, Genovesi P, Maris V, Wardle DA, Aronson J, et al. Impacts of biological invasions: what’s what and the way forward. Trends Ecol Evol. 2013;28:58–66.

Vilà M, Espinar JL, Hejda M, Hulme PE, Jarošík V, Maron JL, et al. Ecological impacts of invasive alien plants: a meta-analysis of their effects on species, communities and ecosystems. Ecol Lett. 2011;14:702–8.

Dickie IA, Bufford JL, Cobb RC, Desprez-Loustau M-L, Grelet G, Hulme PE, et al. The emerging science of linked plant–fungal invasions. New Phytol. 2017;215:1314–32.

Mallon CA, van Elsas JD, Salles JF. Microbial invasions: the process, patterns, and mechanisms. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:719–29.

Van der Putten WH, Klironomos JN, Wardle DA. Microbial ecology of biological invasions. ISME J. 2007;1:28.

Gladieux P, Feurtey A, Hood ME, Snirc A, Clavel J, Dutech C, et al. The population biology of fungal invasions. Mol Ecol. 2015;24:1969–86.

Dickie IA, Bolstridge N, Cooper JA, Peltzer DA. Co-invasion by Pinus and its mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 2010;187:475–84.

Traveset A, Richardson DM. Mutualistic interactions and biological invasions. Ann Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2014;45:89–113.

Schwartz MW, Hoeksema JD, Gehring CA, Johnson NC, Klironomos JN, Abbott LK, et al. The promise and the potential consequences of the global transport of mycorrhizal fungal inoculum. Ecol Lett. 2006;9:501–15.

Van der Heijden MGA, Martin F, Selosse M-A, Sanders I. Mycorrhizal ecology and evolution: the past, the present and the future. New Phytol. 2015;205:1406–23.

Rivera Y, Kretzer AM, Horton TR. New microsatellite markers for the ectomycorrhizal fungus Pisolithus tinctorius sensu stricto reveal the genetic structure of US and Puerto Rican populations. Fungal Ecol. 2015;13:1–9.

Selosse M-A, Jacquot D, Bouchard D, Martin F, Le Tacon F. Temporal persistence and spatial distribution of an American inoculant strain of the ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete Laccaria bicolor in a French forest plantation. Mol Ecol. 1998;7:561–73.

Vellinga EC, Wolfe BE, Pringle A. Global patterns of ectomycorrhizal introductions. New Phytol. 2009;181:960–73.

Pringle A, Adams RI, Cross HB, Bruns TD. The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:817–33.

Hayward J, Horton TR, Pauchard A, Nunez MA. A single ectomycorrhizal fungal species can enable a Pinus invasion. Ecology. 2015;96:1438–44.

Nuñez MA, Horton TR, Simberloff D. Lack of belowground mutualisms hinders Pinaceae invasions. Ecology. 2009;90:2352–9.

Gazol A, Zobel M, Cantero JJ, Davison J, Esler KJ, Jairus T, et al. Impact of alien pines on local arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities—evidence from two continents. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2016;92:fiw073.

Remigi P, Faye A, Kane A, Deruaz M, Thioulouse J, Cissoko M, et al. The exotic legume tree species Acacia holosericea alters microbial soil functionalities and the structure of the arbuscular mycorrhizal community. Appl Env Microbiol. 2008;74:1485–93.

Nunez MA, Dickie IA. Invasive belowground mutualists of woody plants. Biol Invasions. 2014;16:645–61.

Bogar LM, Dickie IA, Kennedy PG. Testing the coinvasion hypothesis: ectomycorrhizal fungal communities on Alnus glutinosa and Salix fragilis in New Zealand. Divers Distrib. 2015;21:268–78.

Moora M, Berger S, Davison J, Öpik M, Bommarco R, Bruelheide H, et al. Alien plants associate with widespread generalist arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal taxa: evidence from a continental-scale study using massively parallel 454 sequencing. J Biogeo. 2011;38:1305-17.

Tedersoo L, Suvi T, Beaver K, Kõljalg U. Ectomycorrhizal fungi of the Seychelles: diversity patterns and host shifts from the native Vateriopsis seychellarum (Dipterocarpaceae) and Intsia bijuga (Caesalpiniaceae) to the introduced Eucalyptus robusta (Myrtaceae), but not Pinus caribea (Pinaceae). New Phytol. 2007;175:321-33.

Jairus T, Mpumba R, Chinoya S, Tedersoo L. Invasion potential and host shifts of Australian and African ectomycorrhizal fungi in mixed eucalypt plantations. New Phytol. 2011;192:179–87.

Bahram M, Koljalg U, Kohout P, Mirshahvaladi S, Tedersoo L. Ectomycorrhizal fungi of exotic pine plantations in relation to native host trees in Iran: evidence of host range expansion by local symbionts to distantly related host taxa. Mycorrhiza. 2013;23:11–19.

Moeller HV, Dickie IA, Peltzer DA, Fukami T. Mycorrhizal co-invasion and novel interactions depend on neighborhood context. Ecology. 2015;96:2336–47.

Diez J. Invasion biology of Australian ectomycorrhizal fungi introduced with eucalypt plantations into the Iberian Peninsula. Biol Invasions. 2005;7:3–15.

Ducousso M, Duponnois R, Thoen D, Prin Y. Diversity of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Eucalyptus in Africa and Madagascar. Int J Res. 2012;2012:450715.

Põlme S, Bahram M, Kõljalg U, Tedersoo L. Biogeography and specificity of ectomycorrhizal fungi of Coccoloba uvifera. In: Tedersoo L, editor. Biogeography of mycorrhizal symbiosis. Berlin: Springer; 2017. p. 345–59.

Tedersoo L, May TW, Smith ME. Ectomycorrhizal lifestyle in fungi: global diversity, distribution, and evolution of phylogenetic lineages. Mycorrhiza. 2010;20:217–63.

Séne S, Avril R, Chaintreuil C, Geoffroy A, Ndiaye C, Diédhiou AG, et al. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities of Coccoloba uvifera (L.) L. mature trees and seedlings in the neotropical coastal forests of Guadeloupe (Lesser Antilles). Mycorrhiza. 2015;25:547–59.

Howard RA. Studies in the genus Coccoloba, X. New species and a summary distribution in South America. J Arn Arbor. 1961;42:87–95.

Bâ AM, McGuire KL, Diédhiou AG. Ectomycorrhizal symbioses in tropical and neotropical forests. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2014.

Séne S. Analyse de la diversité ectomycorhizienne du Coccoloba uvifera en zone d’origine et en zone d’introduction. PhD thesis, Université Antilles-Guyane, Pointe-à-Pitre, France; 2015.

Wilson AW, Binder M, Hibbett DS. Diversity and evolution of ectomycorrhizal host associations in the Sclerodermatineae (Boletales, Basidiomycota). New Phytol. 2012;194:1079–95.

Richard F, Millot S, Gardes M, Selosse M-A. Diversity and structuration by hosts of the below-ground mycorrhizal community in an old-growth Mediterranean forest dominated by Quercus ilex L. New Phytol. 2005;166:1011–23.

Rousset F. Genepop’007: a complete re-implementation of the Genepop software for Windows and Linux. Mol Ecol Res. 2008;8:103–6.

Garza JC, Williamson EG. Detection of reduction in population size using data from microsatellite loci. Mol Ecol. 2001;10:305–18.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59.

Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Res. 2010;10:564–7.

Koljalg U, Larsson KH, Abarenkov K, Nilsson RH, Alexander IJ, Eberhardt U, et al. UNITE: a database providing web-based methods for the molecular identification of ectomycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 2005;166:1063–8.

Ebenye HCM, Taudière A, Niang N, Ndiaye C, Sauve M, Awana ON, et al. Ectomycorrhizal fungi are shared between seedlings and adults in a monodominant Gilbertiodendron dewevrei rain forest in Cameroon. Biotropica. 2017;49:256–67.

Bandou E, Lebailly F, Muller F, Dulormne M, Toribio A, Chabrol J, et al. The ectomycorrhizal fungus Scleroderma bermudense alleviates salt stress in seagrape (Coccoloba uvifera L.) seedlings. Mycorrhiza. 2006;16:559–65.

Bechem EET, Alexander IJ. Mycorrhiza status of Gnetum spp. in Cameroon: evaluating diversity with a view to ameliorating domestication efforts. Mycorrhiza. 2012;22:99–108.

Tedersoo L, Põlme S. Infrageneric variation in partner specificity: multiple ectomycorrhizal symbionts associate with Gnetum gnemon (Gnetophyta) in Papua New Guinea. Mycorrhiza. 2012;22:663–8.

Douglas AE, Werren JH. Holes in the hologenome: why host-microbe symbioses are not holobionts. MBio. 2016;7:e02099–15.

Selosse M-A, Richard F, He X, Simard SW. Mycorrhizal networks: des liaisons dangereuses? Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:621–8.

Wilkinson DM. The role of seed dispersal in the evolution of mycorrhizae. Oikos. 1997;78:394–6.

Taschen E, Rousset F, Sauve M, Benoît L, Dubois M-P, Richard F, et al. How the truffle got its mate: insights from genetic structure in spontaneous and managed Mediterranean populations of Tuber melanosporum. Molr Ecol. 2016;25:5611–27.

Vincenot L, Selosse M-A. Population biology and ecology of ectomycorrhizal fungi. In: Tedersoo L, editor. Biogeography of mycorrhizal symbiosis. Berlin: Springer; 2017. p. 39–59.

Douglas AE. Conflict, cheats and the persistence of symbioses. New Phytol. 2008;177:849–58.

Sachs JL, Wilcox TP. A shift to parasitism in the jellyfish symbiont Symbiodinium microadriaticum. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2006;273:425–9.

Ramadhani I, Sukarno N, Listiyowati S. Basidiospores attach to the seed of Shorea leprosula in lowland tropical dipterocarp forest and form functional ectomycorrhiza on seed germination. Mycorrhiza. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-017-0798-4.

Rousset F. Genetic differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation by distance. Genetics. 1997;145:1219–28.

Slatkin M. Isolation by distance in equilibrium and non‐equilibrium populations. Evolution. 1993;47:264–79.

McGuire KL. Common ectomycorrhizal networks may maintain monodominance in a tropical rain forest. Ecology. 2007;88:567–74.

Bever JD, Mangan SA, Alexander HM. Maintenance of plant species diversity by pathogens. Ann Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2015;46:305–25.

Nei M. Molecular evolutionary genetics. New York: Columbia University Press; 1987.

Dickie IA, Bennett BM, Burrows LE, Nuñez MA, Peltzer DA, Porté A, et al. Conflicting values: ecosystem services and invasive tree management. Biol Invasions. 2014;16:705–19.

Hulme PE. Trade, transport and trouble: managing invasive species pathways in an era of globalization. J Appl Ecol. 2009;46:10–18.

Acknowledgements

We thank three referees for revisions, David Marsh for English corrections, and the Service de Systématique Moléculaire (UMS2700 MNHN/CNRS) for its facilities. Seynabou Séne received grants from the Guadeloupe Region, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Ministry of Education and Research of Senegal, World Federation of Scientists, and the Laboratoire Mixte International-Adaptation des Plantes et microorganismes associés aux Stress Environnementaux (Dakar).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Séne, S., Selosse, MA., Forget, M. et al. A pantropically introduced tree is followed by specific ectomycorrhizal symbionts due to pseudo-vertical transmission. ISME J 12, 1806–1816 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0088-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0088-y

This article is cited by

-

Using the ectomycorrhizal symbiosis between Coccoloba uvifera L. and Scleroderma bermudense Coker to restore a degraded coastal sand dune in Cuba

Trees (2024)

-

Quo vadis? Historical distribution and impact of climate change on the worldwide distribution of the Australasian fungus Clathrus archeri (Phallales, Basidiomycota)

Mycological Progress (2021)

-

Alien ectomycorrhizal plants differ in their ability to interact with co-introduced and native ectomycorrhizal fungi in novel sites

The ISME Journal (2020)

-

Soil spore bank in Tuber melanosporum: up to 42% of fruitbodies remain unremoved in managed truffle grounds

Mycorrhiza (2019)

-

On mycorrhizal individuality

Biology & Philosophy (2019)