Abstract

Introduction

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is most caused by lumbar disc herniation, and the associated treatment involves prompt surgical decompression. Rarer causes of CES include perineural (Tarlov) cysts.

Clinical presentation

A 62-year-old female with history of rheumatoid arthritis, hip and knee replacements, and chronic low back pain presented with worsening back pain, left leg weakness and pain for 6 weeks, and bowel/bladder incontinence with diminished sensation in the perianal region for 24 h prior to presentation. MRI demonstrated severe spinal stenosis at L4-S1, central disc herniation at L5-S1, and compression of the cauda equina, consistent with CES. A lumbar decompression was performed. Patient did well at 2-week follow up, but presented 5 weeks post-discharge with increased left leg pain/weakness and genitalia anesthesia. Imaging was unremarkable. Two months later, the patient presented with diminished sensation in the buttocks and bilateral lower extremities and bowel/bladder incontinence. Imaging demonstrated a large cystic presacral mass with involvement of the left sciatic foramen and S3 neural foramen. A team of plastic, orthopedic, and neurological surgeons performed an S3 sacral laminectomy, foraminotomy, partial sacrectomy, and S3 rhizotomy, and excision of the large left hemorrhagic pudendal mass. Final pathology demonstrated a perineural cyst with organizing hemorrhage. On follow-up, the patient’s pain and weakness improved.

Conclusion

CES-like symptoms were initially attributed to a herniated disk. However, lumbar decompression did not resolve symptoms, prompting further radiographic evaluation at two separate presentations. This represents the first reported case of a pudendal tumor causing symptoms initially attributed to a herniated disc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is characterized by urinary retention, sciatica, leg weakness, back pain, and saddle anesthesia [1]. CES occurs due to compression of the lumbosacral spinal canal and is most commonly caused by disc herniation [2]. Treatment involves decompression, and delaying treatment over 48 h results in poorer outcomes [3].

We describe a patient who presented with classic CES symptoms. Imaging demonstrated severe lumbosacral stenosis from central disc herniation, prompting a decompression. However, the patient presented twice in following months for worsening symptoms, and workup revealed a pudendal nerve tumor. This represents the first reported case of a pudendal tumor causing symptoms initially attributed to a herniated disc.

Case presentation

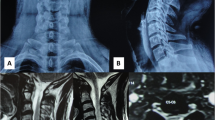

A 62-year-old female with rheumatoid arthritis, left total hip replacement and bilateral total knee replacements, and chronic low back pain presented to the emergency department with worsening back pain and left lower extremity radiculopathy for 6 weeks. Patient described pain as “ripping,” stating it radiated from her back and left groin to her posterior thigh to her left heel. Patient had difficulty ambulating, and developed bowel and bladder incontinence with decreased rectal tone and diminished perianal sensation for 24 h prior to presentation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated severe spinal stenosis at L4-S1, central disc herniation at L5-S1 and compression of the cauda equina (Fig. 1). The MRI was a lumbar series so did not extend caudally enough to demonstrate a sacral mass; sagittal and parasagittal views did not reveal a cyst or mass (Supplementary Fig. 1). A posterior lumbar L3-5 decompression was performed the following day. Patient was discharged to home on postoperative day 2 and had no bowel/bladder incontinence at 2-week follow-up.

Five weeks post-discharge, the patient presented to the emergency department with left leg pain/weakness and genital anesthesia. MRI showed good decompression at the previous surgical site without any acute findings (Fig. 2). Patient was admitted, given intravenous morphine and dexamethasone for pain, and discharged home on hospital day 3.

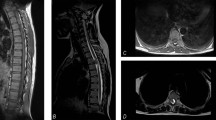

Two months later, she was transferred to our institution after presenting at an outside hospital with 4 days of diminished sensation to light touch and pain in the buttocks and left lower extremity and bowel/bladder incontinence after an epidural steroid injection. Outside imaging demonstrated a large, cystic presacral mass with involvement of the left sciatic foramen and S3 neural foramen (Fig. 3). A CT-guided biopsy was performed, and final pathology demonstrated necrotic organizing tissue. After multidisciplinary tumor board discussion, a joint team of plastic, orthopedic, and neurological surgeons performed a multidisciplinary approach to resecting the lesion.

After exposure of the mass, the associated nerve was identified with free electromyography. The cyst was noted to be firm, and was decompressed with expulsion of chronic hemorrhagic material. Cephalad dissection continued until reaching the sacrum. A sacral laminectomy and left S3 foraminotomy were then performed. The mass was identified in the S3 foramen and appeared to be in continuity with the S3 nerve root. We elected to perform a S3 rhizotomy to decompress the epidural component of the mass. The mass was dissected from the anterior aspect of the sacrum, and removed in its entirety in the peripheral neural space. A neurolysis and decompression of the lumbar plexus to the sciatic nerve was completed, and the pudendal mass was resected to its peripheral attachment. Patient tolerated this procedure well and was discharged to a skilled nursing facility on postoperative day 7. Final pathology of the lesion demonstrated a perineural cyst with organizing hemorrhage.

One week after discharge, the patient endorsed improvement in her back pain and improved sensation in her legs bilaterally. She continued to use membrane stabilizing agents and weaned herself from opioid pain medication. She continued to have urinary incontinence and an indwelling catheter remained in place. At 2-month follow-up, the patient was taught intermittent self-catheterization. Patient did well with intermittent self-catheterization and was able to resume sexual activity. Continued follow-up is planned.

Discussion

This is the first report of a presacral pudendal mass causing CES-mimicking symptoms that prompted a lumbar decompression. Given the patient’s superimposed lumbar degenerative disease, her initial presentation was believed to be CES. Hemorrhage of the cyst with subsequent clot formation and resorption likely led to the relapsing/remitting nature of symptoms. The lumbar disc herniation seen on initial imaging likely contributed to her symptoms, and also likely contributed to her short-term relief after the decompressive surgery.

The patient’s mass, a perineural cyst (Tarlov cyst), has a global prevalence between 2.5–6.3% [4], a typically sacral lesion found most often at S2-S3 [5]. These cysts are generally incidental findings, and only 16% of spinal Tarlov cysts are associated with neurological symptoms [4]. The cysts can grow via a ball-valve mechanism, and can eventually cause compression [6]. Hydrostatic and pulsatile forces of cerebrospinal fluid flow can cause Tarlov cysts to grow [7], and so the initial decompressive surgeries could have caused growth and worsening of the perineurial cyst. Among patients with persistent genital arousal disorder, and pudendal neuralgia, 37.9% and 16.1%, respectively, had a Tarlov cyst [4]. With surgery, patients with symptomatic cysts experience complete or significant reduction in pain and improvement in sensation [8].

Other tumors have been reported to cause similar symptoms as our patient, and were likewise overlooked on initial imaging. A 34-year-old with a 3.2 × 2.8 × 3.2-cm pudendal schwannoma presented with perianal pain, fasciculations, and paresthesias for 10 years [9]. Imaging taken 5 years prior demonstrated the mass, which was not commented on, and the lesion grew 1.2 cm in 5 years. After resection, the patient’s symptoms fully resolved. Additionally, a 33-year-old male presented with low back pain and unilateral radiculopathy that progressed to severe paresis [10]. An MRI showed a presacral mass at the L5 root level, but was initially overlooked and was diagnosed with psychogenic paresis. However, after additional imaging, the lesion was identified and surgical resection yielded complete symptom resolution.

We propose the following algorithmic approach to identify rare causes of CES in older adults and avoid delayed diagnosis. First, if patient presents with classic symptoms, including saddle anesthesia, urinary retention, and lower extremity pain or weakness, imaging should be done. We support that imaging of both the lumbar and sacral spine should be done, particularly if symptoms occur in the sacral nerve distribution, such as the posterior thigh, lower leg, and anal area. Secondly, in individuals with degenerative spine disease, we support specific inspection of imaging for others causes of CES, including neoplasms, vascular lesions, infection [11]. We also support specific history gathering regarding constipation, chemotherapy, and radiation. Lastly, if disc herniation is found to be the cause and surgery is pursued, the postoperative imaging should also be particularly reviewed for the other etiologies of CES detailed above.

The value in this case is that the patient was initially treated for a herniated disk, which was present on imaging, also localized to her constellation of symptoms, and is the most common cause of CES [2]. However, after lumbar decompression, symptoms did not ultimately resolve, prompting further radiographic evaluation on two separate presentations to different hospitals. After the presacral mass was identified and removed by an interdisciplinary team of surgeons, the patient’s pain and paresthesias permanently improved. We demonstrate a novel method to remove this mass, with a S3 sacral laminectomy, foraminotomy, partial sacrectomy, and S3 rhizotomy.

In the future, when patients present with CES, we urge for careful examination of imaging given the rarer causes of CES symptoms and the high prevalence of non-contributory spinal findings (i.e., disk herniations), particularly in aging populations.

Change history

20 September 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-022-00547-1

References

Quaile A. Cauda equina syndrome-the questions. Int Orthop. 2019;43:957–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-4208-0.

Spector LR, Madigan L, Rhyne A, Darden B, Kim D. Cauda equina syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:471–9. https://doi.org/10.5435/00124635-200808000-00006.

Thakur JD, Storey C, Kalakoti P, Ahmed O, Dossani RH, Menger RP., et al. Early intervention in cauda equina syndrome associated with better outcomes: a myth or reality? Insights from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database (2005-11). Spine J. 2017;17:1435–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2017.04.023.

Klepinowski T, Orbik W, Sagan L. Global incidence of spinal perineural Tarlov’s cysts and their morphological characteristics: a meta-analysis of 13,266 subjects. Surg Radio Anat. 2021;43:855–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-020-02644-y.

Lim VM, Khanna R, Kalinkin O, Castellanos ME, Hibner M. Evaluating the discordant relationship between Tarlov cysts and symptoms of pudendal neuralgia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:70.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.07.021.

Langdown AJ, Grundy JRB, Birch NC. The clinical relevance of Tarlov cysts. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:29–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.bsd.0000133495.78245.71.

Acosta FL, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Schmidt MH, Weinstein PR. Diagnosis and management of sacral Tarlov cysts. Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E15. https://doi.org/10.3171/foc.2003.15.2.15.

Elsawaf A, Awad TE, Fesal SS. Surgical excision of symptomatic sacral perineurial Tarlov cyst: case series and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:3385–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4584-3.

Mazzola CR, Power N, Bilsky MH, Robert R, Guillonneau B. Pudendal schwannoma: a case report and literature review. Can Urol Assoc J. 2014;8:E199–203. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.1734.

Tschugg A, Tschugg S, Hartmann S, Rhomberg P, Thomé C. Far caudally migrated extraforaminal lumbosacral disc herniation treated by a microsurgical lateral extraforaminal transmuscular approach: case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016;24:385–8. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.7.SPINE15342.

Long B, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M. Evaluation and management of cauda equina syndrome in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38:143–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158402.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed and provided approval on this case report.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The patient signed a consent for use of her records for deidentified research purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahajan, U.V., Labak, K.B., Labak, C.M. et al. Pudendal tumor mimicking cauda equina syndrome and acute radiculopathy: case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 8, 71 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-022-00537-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-022-00537-3