Abstract

Introduction

Septic arthritis of a facet joint (SAFJ) is a relatively rare medical entity and the lumbar segment is its most frequent location. Although unusual, a spinal epidural abscess (SEA) can occur as a complication of SAFJ and possibly damage the spinal cord.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old woman presented with acute right dorsal pain, fever, loss of sphincters control, and paraparesis without causal factor. Forty-eight hours after the symptoms started, imaging revealed a thoracic posterior epidural collection causing compression of the spinal cord and features suggestive of septic arthritis of right T5-T6 facet joint. She underwent an urgent laminectomy and drainage of the abscess. Both blood and abscess cultures isolated Staphylococcus aureus. A diagnosis of complete paraplegia grade A of the ASIA (American Spinal Injury Association) Impairment Scale (AIS) with neurologic level T10 was made 5 days after surgery. She took 3 months of an intensive rehabilitation program at our Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine ward. With an unexpected favorable evolution, both neurological and functional, she was discharged with an incomplete paraplegia AIS D and functionally independent in all tasks.

Discussion

This case reveals an infrequent medical condition on a rarely affected spinal segment. An early diagnosis and proper treatment of SAFJ and SEA are of major importance to avoid severe related consequences. Patients with spinal cord injury with severe neurological deficits due to these conditions greatly benefit from an interdisciplinary rehabilitation program to improve neuromotor and functional status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Septic arthritis of a facet joint (SAFJ) is considered a relatively rare medical entity. Its exact incidence is unknown, with about 50 cases reported worldwide [1]. It represents about 4–20% of all spinal infections, contrasting with the higher incidence rates of spondylodiscitis [2]. The main dissemination pathway described in literature is via hematogenous spread [3] or contiguous spread from an infection in the vertebral body [4]. Unilateral facet joint involvement is normally associated with previous medical intervention, such as epidural injections or acupuncture [5]. The most frequent location of SAFJ is the lumbar segment (86–97%) [2]. The clinical presentation can be very sparse or may mimic a spondylodiscitis [2]. Spinal epidural abscess (SEA) is occasionally associated with SAFJ [5] and it can damage the spinal cord by direct compression or local ischemia [6]. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of these conditions are of major importance in order to prevent or minimize neurological deficits that can be devastating and improve the prognosis [6].

Case report

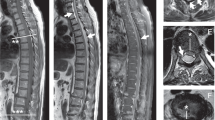

We report the case of a 53-years-old healthy and previously independent woman, that went to the emergency room (ER) with an acute intense right dorsal pain, ongoing for a day, without prior trauma or other known causal factors. She was initially discharged with oral analgesia but during the following days the pain persisted with appearance of fever (38,5° Celsius), loss of bowel and bladder control and rapidly progressive paraparesis. Within less than 48 h she returned to the ER and was transferred to our hospital. At admission the patient had flaccid paraparesis (manual muscle testing grade 1 in all segments of the lower limbs) sensory loss below T7, bilateral extension in plantar cutaneous reflex and loss of sphincter control. Blood tests showed a mild leukocytosis with left deviation (11.82 × 109/L with 85.3% neutrophils), and CT-scan revealed a posterior epidural collection between levels T4 and T9, about 5 mm thick, along with possible compression of the spinal cord at the myeloradicular space. Additional study with Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1) revealed a multiloculated extensive posterior epidural collection, extending from level T2 to T9, with greater thickness at levels T4 to T6 (slight right predominance at levels T5 and T6), causing compression of the spinal cord; presence of osseous edema at right T5-T6 facet joint with a small intra-articular effusion, thickening and reinforcement of the sign of the adjacent paravertebral tissues. The aspects described were compatible with posterior epidural abscess secondary to septic arthritis of right T5-T6 facet joint. An urgent laminectomy of T4-T6 and drainage of the abscess was performed. Abundant solid (granulomatous) and liquid (purulent) material was found and microbiological and mycobacteriological samples were taken.

Empiric antibiotic therapy was immediately initiated with ceftriaxone and metronidazole. Blood culture allowed the identification of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and antibiotic therapy was consequently changed to flucloxacillin.

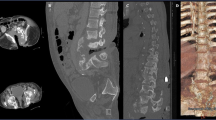

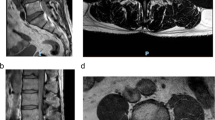

The patient was transferred to Infectious Disease Department (ISD) after surgery and maintained antibiotic therapy (flucloxacillin 12 g/day) for a total of 6 weeks. Laboratory tests revealed a progressive normalization of inflammatory markers; urine culture and echocardiogram ruled out other possible sources of hematogenous seeding. New MRI (Fig. 2) showed post-surgical changes with removal of the loculated posterior epidural component and maintenance of inflammatory/infectious changes of the structures adjacent to the right posterior facet joint T5-T6 and spinal edema at level T7-T8.

She was first observed by a physiatrist from our PRM department soon after her arrival at ISD. At examination, diagnosis was complete spinal cord injury AIS A, with neurologic level T10, hypotonia and absence of active movements in the lower limbs, preserved muscular strength in the upper limbs and neuropathic pain in lower abdominal quadrants and thighs, for which pharmacologic therapy was prescribed (amitriptyline and gabapentin) and fine-tuned during the hospital stay (nonetheless, these symptoms alleviated and the therapy was reduced).

The patient began a daily rehabilitation program in the ISD. The management of the neurogenic bowel dysfunction consisted of dietary fiber and fluid intake recommendations, oral laxatives and rectal pharmacological therapy.

The transfer to our PRM ward occurred 5 weeks after surgery, presenting at admission an incomplete paraplegia AIS C, with neurological level T10, hypotonia of the lower limbs except for hamstrings (grade 1 in Modified Ashworth Scale - MAS) and plantar flexors of the foot (grade 2 in MAS); absent voluntary anal contraction and no deep anal pressure; normal range of motion of all joints; manual muscular strength grade 1 in left hip flexors, ankle dorsiflexors and plantar flexors, both long toe extensors and grade 0 in all other segments; hypoesthesia and hypoalgesia below level T10; abolished lower limb proprioception; abolished Achilles reflex bilaterally; plantar cutaneous reflex in extension; effective static seating balance and ineffective dynamic; and she used a manual self-propelled wheelchair. On functional evaluation she was moderate dependent at bathing, needed maximal assistance for transfers and dressing the lower body, and total assistance for sphincter control. The Barthel index (BI) score was 30.

She integrated an interdisciplinary rehabilitation program coordinated by a physiatrist that included medical, nursing and social care, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and psychology. The main goals were improving motor control of the trunk, optimization of bladder and intestinal functions, prescription of assistive devices and improving capability for the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and participation. The rehabilitation program consisted of:

-

- Two daily 60-min session of physical therapy, 5 days per week, involving: passive range-of-motion (ROM) exercises for the lower limbs, with stretching of the main muscle-tendon units; active ROM exercises for the trunk and upper limbs; static and dynamic muscle strengthening exercises of the main muscle groups of the upper limbs and muscle strengthening of core muscles; motor sequence exercises; dynamic seated balance exercises; transfer training; readaptation of orthostatic position using a static standing frame;

-

- One 60-min session of occupational therapy, 5 days per week, consisting of activities for ADL training, focusing on dressing the lower body, bathing and transfers, study and training with assistive devices;

-

- Throughout every day at the ward, transfer and ADL training by the nursing staff.

During her stay at PRM ward, patient’s neuromotor and functional condition progressively improved. At physiotherapy and occupational therapy departments, the rehabilitation program was adapted with progressive lower-limb muscular strengthening, standing balance exercises and assisted gait training in a smooth surface with a walker. At discharge, the woman had incomplete paraplegia AIS D, with neurological level L1, strength was globally graded 5 in upper limbs and 4 in the lower limbs, except for right dorsiflexors and plantarflexors (grade 2); unchanged muscle tone; normal light touch and pin prick sensations until L1 (and diminished below); effective seating and static standing balance; ability to walk for short distances with two crutches (for long distances, a manual self-propelled wheelchair was used). She continued the bowel program with oral laxative and stimulant suppository on alternate days and bladder management with intermittent self-catheterization every 4 h (a renal and bladder ultrasound was performed which showed no alterations and a urodynamic study was postponed due to urinary tract infection). Functionally, at time of discharge she was completely independent, with modified independence at bathing (using a bath chair), toileting, transfers, dressing the lower body and sphincter control. The BI was 95.

MRI was repeated again 2 months after surgery (Fig. 3), revealing a reduction in thickness and extension of the signal reinforcement of the posterior epidural space and no spinal cord compression. Due to radiological improvement and absence of clinical or laboratory criteria of infection, the dose of flucloxacillin was reduced to 8 g/day until completeness of 8 weeks of treatment.

There were, however, some complications: urinary tract infection due to Enterococcus faecium; bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome, which required development of a costume-made night orthosis as well as corticoanesthetic ultrasound-guided injections, with symptomatic resolution; identification in urine culture of Klebsiella pneumoniae with the ability to produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamases which was interpreted as an urinary tract colonization and therefore isolation precautions were taken.

Discussion

SAFJ is a rare clinical entity that is included in the group of spinal infections. The exact pathogenesis is multifactorial [5] and several risk factors have been described, such as immunocompromised conditions like diabetes mellitus and chronic liver disease, alcoholism and corticosteroid therapy [2]. Iatrogenic causes are also plausible like epidural injections, acupuncture or spinal surgery [5]. However, it has been stated that more than 60% of patients with SAFJ don’t show any systemic risk factors [7]. Previously reported epidemiology reveals that the most common pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus [2, 4, 7].

An important and often difficult differential diagnosis of SAFJ is spondylodiscitis. In both entities, the most commonly affected area is the lumbar and lumbosacral segments, while thoracic involvement is rare (4.5%) [2, 7]. SAFJ generally presents as a persistent back pain, often unilateral, with possible radiation to the flank or buttocks, and fever [1, 4]. Compared to spondylodiscitis, the symptoms tend to be more acute and severe in early stages [7].

The development of severe neurological deficits is very uncommon (less than 10% of cases) [1] and usually occurs due to extension of the infection into the epidural or intradural space [8]. Despite the majority of SEA being associated with vertebral osteomyelitis and affecting the anterior epidural space [9], SEA and paraspinal muscle abscess can also be complications of SAFJ. This can be explained by the narrow facet joint articular cavity, which can lead to the easy spread of the infection to the epidural space or paravertebral muscles, when the ventral aspect of the articular capsule is ruptured [10]. The clinical presentation depends on its location but is non-specific which can make diagnosis more difficult [6]. In a relatively small percentage of cases (10–15%) a classic symptom triad can be present: back pain, fever and neurological deterioration [9]. There are several mechanisms suggested for the spinal cord injury correlated with SEA: direct compression, ischemia or septic thrombophlebitis [6]. The progression of neurological deficits is highly variable [9].

It is required to identify the microorganism causing the infection. As hematogenous spread of SAFJ is so common, is it important to search for possible sources of infections, and blood cultures are mandatory [2]. If positive, the microorganism is assumed to be responsible for the process [7]. Other sources of infection should be excluded.

Diagnosis of SAFJ is difficult and a high level of suspicion is necessary. As stated above, this condition is hard to distinguish from spondylodiscitis. The clinical manifestations and laboratory findings can be similar, with inflammatory markers generally elevated [9, 11]. Plain radiography is not useful in early stages as abnormalities only appear 6–12 weeks after the onset of symptoms [2]. CT-images only show facet joint destruction about 1 week after the onset of symptoms [3]. MRI remains the gold standard for image diagnosis, being a highly sensitive and specific method. It allows early diagnosis, evaluation of the spinal cord, and identification of infection spread to structures including the epidural space and/or nearby paraspinal tissues [5, 7, 8, 11].

The first treatment choice rests on antibiotics. It is suggested that the duration of treatment should be 4–6 weeks, but should be continued until the pain has disappeared and inflammatory markers are normalized [11]. Surgical drainage and debridement are reserved for patients with severe neurological dysfunction [3]. In SEA without neurological symptoms, conservative treatment with intravenous antibiotics with careful monitoring can be tried [6, 9]. The duration of treatment varies between 4 and 16 weeks, but resolution of the abscess usually is achieved after 4–6 weeks [9]. If this intervention fails, a CT-guided needle aspiration can be performed [9]. In other cases, the only effective treatment for SEA is rapid surgical intervention with decompressive laminectomy and debridement of infected tissues followed by antibiotic treatment [6]. The neurologic outcome correlates strongly with the duration of deficits prior to surgery and their severity. If complete paralysis is present for about 48–72 h, it’s unlikely that neurological deficits will improve after surgery [9].

Regarding the prognosis of neurological recovery in spinal cord injury, it is known that patients with complete spinal cord injury (AIS A) at the first examination have very few chances of neurological recovery. Upon diagnosis of AIS A at 72 h post-injury, 84% of the patients will remain AIS A at 1-year follow-up, 8% will convert to AIS B, 5% to AIS C and 3% to AIS D. However, if the first examination is made at 30 days post-injury and an AIS A diagnosis is made, 96% will remain AIS A at 1-year follow-up and 5% will converted to AIS C and D (2,5% each) [12]. Regarding recovery of walking function, there is evidence that it is comparable between traumatic and non-traumatic spinal cord injuries [12].

In our case, the individual had a SAFJ with no risk factors identified, indicating that this condition can appear in immune-competent patients. Moreover, the occurrence of an epidural abcess in the thoracic spine is rare. Rapid diagnosis was established with identification of both arthritis of the facet joint and posterior SEA via MRI. Due to compression of the spinal cord, severe neurological deficits were present requiring an urgent surgical procedure with laminectomy and drainage of the abscess. The isolation of Staphylococcus aureus both in blood and SEA cultures identified the most common microorganism described in literature for SAFJ. Our hypothesis is that SAFJ occurred via hematogenous spread with unknown origin, which lead to SEA by contiguous spread. Our patient presented a surprisingly favorable neuromotor recovery, starting with a diagnosis of complete paraplegia AIS A with neurological level T10. She was discharged 4 months after surgery with an incomplete paraplegia AIS D with neurological level L1. The functional improvement should also be noted, with an additional 65 points in BI score.

In conclusion, physicians should be aware of the existence of SAFJ and SEA, as early diagnosis and proper treatment can prevent potential severe consequences and improve the prognosis. As seen in this clinical case, in the event of spinal cord injury with severe neurological deficits due to these conditions, a rehabilitation program with an interdisciplinary team has an important role in neuromotor and functional recovery of these patients.

References

Mas-Atance J, Gil-García MI, Jover-Sáenz A, Curià-Jové E, Jové-Talavera J, Charlez-Marco A, et al. Septic arthritis of a posterior lumbar facet joint in an infant: a case report. Spine (Philos Pa 1976). 2009;34:E465–E468. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a4e64b.

Huguet S, Ibáñez N, Bernaus M, Font-Vizcarra L. Acute medullar compression secondary to a septic arthritis of a thoracic facet joint: a case report and review of literature. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2018;4:80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0117-0.

Setoue T, Nakamura JI. A rare case of thoracic pyogenic facet joint infection. Case Rep. Orthop. 2019;2019:8252986. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8252986.

Rhyu KW, Park SE, Ji JH, Park I, Kim YY. Pyogenic arthritis of the facet joint with concurrent epidural and paraspinal abscess: a case report. Asian Spine J. 2011;5:245–9. https://doi.org/10.4184/asj.2011.5.4.245.

Harries LW, Watura R. Septic arthritis of unilateral lumbar facet joint with contiguous abscess, without prior intervention. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr0920114849 https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.09.2011.4849.

Rosc-Bereza K, Arkuszewski M, Ciach-Wysocka E, Boczarska-Jedynak M. Spinal epidural abscess: common symptoms of an emergency condition. A case report. Neuroradiol J. 2013;26:464–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/197140091302600411.

Narváez J, Nolla JM, Narváez JA, Martinez-Carnicero L, De Lama E, Gómez-Vaquero C, et al. Spontaneous pyogenic facet joint infection. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:272–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.09.003.

Lopes Correia B, Diniz SE, Lopes da Silva E, Rodrigues-Pinto R. Septic arthritis of the lumbar facet joint presenting as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a rare case requiring surgical intervention. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2020;30:175–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-019-02527-y.

Sendi P, Bregenzer T, Zimmerli W. Spinal epidural abscess in clinical practice. QJM. 2008;101:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcm100.

Ogura T, Mikami Y, Hase H, Mori M, Hayashida T, Kubo T. Septic arthritis of a lumbar facet joint associated with epidural and paraspinal abscess. Orthopedics. 2005;28:173–5.

Doita M, Nabeshima Y, Nishida K, Fujioka H, Kurosaka M. Septic arthritis of lumbar facet joints without predisposing infection. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:290–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.bsd.0000211285.91271.b3.

Scivoletto G, Tamburella F, Laurenza L, Torre M, Molinari M. Who is going to walk? A review of the factors influencing walking recovery after spinal cord injury. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00141.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to Pedro Alves and Sofia Amante for the help and information regarding the imagiological point of view.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Plancha da Silva, T., Amaral Silva, M., Santos Boaventura, S. et al. Spinal cord disorder due to spinal epidural abscess secondary to thoracic facet joint septic arthritis—a rare case with a surprising evolution. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 6, 102 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-020-00353-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-020-00353-7