Abstract

Introduction

Cultural and socioeconomic factors influence the risk of sustaining a Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury (TSCI). The standard of management and rehabilitation available to TSCI patients differs greatly between high-income and low-income countries.

Case presentation

We report a 17-year-old male bird hunter, with no prior medical history, presenting with paraplegia and sensory loss from the xiphoid process down after being struck by an arrow in the left lateral side of the neck.

Discussion

Penetrating neck injuries are potentially life threatening because of the complex arrangement of vital structures in the neck. Management of spinal cord trauma resulting from such injuries in low-resource settings is challenging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organisation reported that transport-related causes accounted for almost 70% of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injuries (TSCIs) in Africa [1]. The influence of one’s environment and activities on the risk profile for a spine or Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) is unmistakable. Despite the progressive urbanisation of regions in northern Tanzania associated with an increase in motor traffic levels, TSCIs most commonly occur due to fall injuries, often from trees [2,3,4,5]. It is a reflection of a society where widespread agricultural practices influence daily activities.

Bird hunting is a common practice amongst different tribes living in the rural areas of Tanzania. These tribes include the Sandawe and the Hadza people [6]. Trained hunters use bows and arrows as their equipment, and a missed target or a ricocheting arrow can cause serious injury to anyone standing in the path of the arrow as occurred to the patient described in this case report.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first case report of a TSCI resulting from penetrating neck trauma during bird hunting.

Setting

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) in northern Tanzania is the only health centre in the country with a dedicated SCI rehabilitation unit. The Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Unit (ORU) was inaugurated in 2014 and is a unit run by the team of orthopaedic surgeons, a neurologist, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and nurses. Patients with TSCI’s are initially admitted for acute care to the orthopaedics and trauma wards and transferred to ORU as soon as the acute management is complete. Due to limited space in our rehabilitation unit, transfers from the general ward may be delayed for several weeks.

Case presentation and diagnostics

A 17-year-old male was hunting birds with his companion in central rural Tanzania using bows and arrows as their hunting equipment. His companion had climbed a tree to better spot birds when he marked his prey in the general direction of the individual. He fired a non-poisonous arrow towards his mark which ricocheted off a branch and penetrated the left lateral side of the individual’s neck. This was followed by immediate loss of sensation and strength from the level of the mid-chest downwards. There was no history of impaired consciousness, convulsions or impaired bowel and bladder control. His companion removed the arrow within a few minutes with no significant bleeding from the entry site.

The patient was transported to a health centre on a motorcycle while being supported in a sitting position between two friends. Due to the loss of power and sensation, both his feet dragged on the ground during the 4-hour long transfer and he sustained deep abrasions on the toes of both feet. He was managed with unspecified intravenous fluids and analgesics, as well as antibiotics, ceftriaxone and metronidazole. The wound on the left lateral side of neck was cleaned and sutured. For further management, the patient was referred to KCMC 350 kilometres away and transported in a supine position, again without spinal precautions.

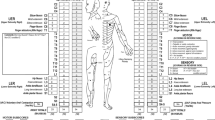

Upon presentation at KCMC 3 days after injury, the patient had a full level of consciousness and was hemodynamically stable, the pupils were equal in size, symmetrical and reacted to light and examination of the upper limbs revealed no motor or sensory deficits. Flaccid paralysis was noted on the lower limbs. There was a sutured 5 centimetre wound on the left lateral side of the neck (Fig. 1) and deep abrasions on the first and second digits of both feet. On examination of the respiratory system, significant findings included reduced chest expansion and an abdominal breathing pattern. Auscultation of the abdomen revealed reduced bowel sounds with an otherwise normal examination. The cardiovascular system examination was normal.

The only imaging modality acutely available and affordable during admission was a cervical x-ray which showed no abnormality.

Diagnosis

The working diagnosis was a thoracic level spinal cord transection secondary to a penetrating neck wound. Due to the high level of entry wound (mid-cervical) relative to the neurological level (upper thoracic) of injury, we also considered a spinal epidural haematoma resulting in ischaemia of the cord secondary to compression. However, the immediate onset of symptoms following entry of the arrow in a rostro-caudal direction into the patient’s neck favoured the former diagnosis.

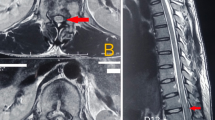

A Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan two and a half months following injury demonstrated extensive signal abnormality in the spinal cord extending from the inferior level of the C7 endplate involving the left anterior horn of the cord, tracking posteriorly at the superior level of the T1 endplate transecting both posterior horns and involving the right side where there is complete involvement of the right hemicord.

Bright T2/Short-T1 Inversion Recovery (STIR) signal intensity within the lesion site signified cerebrospinal fluid replacement. Minimal extramedullary intradural collection anterior to the cord from the mid C7 level to the inferior endplate of T2 reflected a possible haematoma, but there were no features of a compressive complication (Figs 2 and 3).

A Computed Tomography (CT) scan 3 months after injury demonstrated no evidence of a healed cervical or thoracic spine fracture.

Clinical course and outcome

The patient was initially admitted to the Orthopaedics and Trauma ward at KCMC and was treated in a supine position with a two hourly turning schedule. Apart from an x-ray of the cervical spine, further imaging could not be obtained to rule out an expanding haematoma or cervical spine injury during this time.

The patient remained hemodynamically stable but developed bilateral pressure sores over the greater trochanters. The sores were a few millimetres deep with necrotic edges and were managed well with serial bedside debridement and daily dressings. During this time there was no deterioration in his neurological status and the patient was planned for transfer to the rehabilitation unit.

Serial neurological examination demonstrated a gradual, albeit patchy return of vibration, pin prick and joint position sense on the right side of the body corresponding from the T7 dermatome level downwards; on the left side of his body there was absent sensation from the T4 level downwards (See Table 1, ref. [7]).

His lower limbs had rapidly developed spasticity with bilateral upgoing plantar reflexes and a triple flexion response (hip flexion, knee flexion and dorsiflexion of the foot) could be elicited bilaterally by stimulus application on the lateral aspect of the feet. Spasms were satisfactorily controlled with 4 milligrams of oral tizanidine used thrice daily.

Following transfer to the ORU, physiotherapists and occupational therapists worked closely with the patient beginning initially with upper limb strengthening exercises and regular passive mobilisation of the lower limbs. He gradually progressed to bedside sitting exercises and wheelchair transfer and skills training. During his time in ORU he was also trained on bowel management techniques. For bladder management, the patient was initially maintained on a Foley catheter. A few weeks later bladder function was assessed without a catheter; he demonstrated features of a spastic neurogenic bladder. He was maintained on a condom catheter and trained on techniques of continuous intermittent catheterisation to allow for residual urine drainage.

Before his discharge from hospital, a wheelchair was generously donated by a visiting physiotherapist at our centre. After the patient’s in-hospital management was complete, he was discharged to return to his home town—350 km away—after communication with occupational therapists in his region who would be able to assist him with the transition of hospital to home living and continue with his follow-up.

Discussion

We present a 17-year-old male bird hunter who sustained an incomplete spinal cord injury at the T3 level following a penetrating neck injury corresponding to the C5 level.

Several patterns emerge when examining the cause of TSCIs in injured populations; [1] in high-income countries and urban areas of low-income to middle-income countries road traffic crashes and falls in elderly people are the leading causes of injury [8]. However, in some areas of the world, the influence of cultural and socioeconomic factors determines the risk of sustaining a TSCI. Unintended gunshot wounds in Jordan account for a high percentage (25.8%) of TSCIs; this is likely due to traditional practices involving firing guns into the air [9]. Falls from rooftops in Turkey are often reported due to the summertime practice of sleeping on roofs [8]. Over a period of 29 years, the Guttman Institute in Barcelona received 5 patients who sustained cervical level TSCIs following the collapse of human towers [10].

In Northern Tanzania, the most common cause of TSCI’s in a hospital-based cohort was fall injuries [4]. This was commonly observed in young males falling from trees, whose culture dictates that they are stronger and more able to climb trees to forage for food, firewood and cattle feed [5]. Understanding the risk profile of a population is the first step towards developing and implementing primary prevention methods to reduce the incidence of injury.

The individual had not completed primary level education before he sustained his injury as the nearest school was a long distance from his home; the daily commute was too costly and time consuming. He lived in a community of pastoralists and tending cattle after completing primary level education was the considered the norm.

It is also notable that imaging later demonstrated that there was no unstable injury of the spine, the patient was transported in less than ideal circumstances for any trauma victim. A local and referral health centre were both several hours travel away from the site of accident. As a result of being strapped to a motorcycle while paralysed from the mid-chest down, the patient’s feet dragged along the road for a prolonged period of time, resulting in deep abrasions on the toes of both feet. Often, trauma patients in low-income and middle-income countries are brought to hospital in privately owned or public transport vehicles [11,12,13]. Patient positioning is often sub-optimal and individuals accompanying patients have had no formal training in trauma victim handling; a Nigerian review of pre-hospital patient transfer demonstrated a significantly higher mortality rate in patient’s transported in a crouched position [13].

A meticulous physical examination upon initial presentation and during his hospital stay did not reveal any sign of injury to vital structures before entry into the spinal canal. The anatomy of the neck is complex with several vital structures closely webbed in a relatively confined space. The penetrating arrow’s path entirely missed several neural structures (brachial plexus and cervical nerve roots), blood vessels (carotid artery, internal jugular vein and subclavian artery and vein), lymphatic drainage ducts (thoracic duct), bony structures (cervical vertebrae and ribs) and soft tissues (lung apices and trachea) (Fig. 4, an image which has the neck rotated in a similar way as the patient held his when the arrow struck [14]).

Anatomical structures of the lateral aspect of the neck [12]

The patient clearly recalls that he was looking upwards towards the right when he sustained the injury. Considering an entry wound which corresponds to the C5 vertebrae level, a spinal cord lesion at T1 on an MRI scan and the absence of any features which would indicate injury to other vital structures, it appears the arrow entered the patient’s neck at a sharp angle to his vertical axis while his neck was extended and in lateral flexion to the right. The patient only underwent MRI imaging 9 weeks after injury and CT imaging after 13 weeks. Due to financial constraints the patient’s family were unable to afford either. MRI imaging was kindly sponsored by the MRI Centre, and CT imaging by our hospital.

Suprasacral spinal cord lesions typically present with a spastic neurogenic bladder. Detrusor overactivity resulting in reflex bladder emptying may significantly reduce the quality of life of an individual. Anticholinergics may be used to circumvent this, but in our population this often proves challenging due to poor availability and high cost of the drugs. Several plants used in herbal medications have potent dosages of anti-cholinergic compounds [15]. Herbal medication in Tanzania is easily accessible and commonly utilised by the general population [16], however the pharmacology of the drugs is poorly defined and the potential of contamination is quite high. Further research into these compounds may yield a source of regulated and locally sourced anticholinergic medications.

In a utopian setting, our patient would have been transported with spinal precautions (neck collar, laid on a hard board) to a health facility with immediate access to imaging. The penetrating arrow would have been removed in a hospital setting while in the presence of medical professionals trained to manage penetrating neck trauma and any lesion requiring urgent surgical attention would have been attended to within the appropriate time frame. Our experience in this case serves to illustrate the challenges faced by healthcare workers in low-resource settings.

Strained healthcare budgets in low-income countries translate into limited medical resources; the general population’s accessibility to health facilities and the necessary care is further hampered by the cost of treatment, low medical insurance rates [17], long distances to hospitals [18] and poor rehabilitation services [19]. The authors have repeatedly observed that the interplay of these factors often results in late presentation to hospital and a high rate of loss to follow up.

Our patient was managed and underwent rehabilitation in one of only two spine rehabilitation centres in Eastern Africa. The distance from his home to the hospital was 350 kilometres and discharge from in-hospital care was only undertaken after extensive discussions with healthcare personnel in his hometown.

In January 2018, a multidisciplinary spine team was formed comprising of orthopaedic surgeons, a neurologist, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses and medical doctors. Every TSCI injury patient in the hospital is reviewed by this team on a weekly basis. The experience we have garnered over the past year and few months has allowed us to embark on developing an updated SCI protocol for our hospital. The protocol will take into consideration the health resources we have available and will allow us to better manage our TSCI patients.

SCI care in North Tanzania is still in its infant stages. Before we can envision providing more comprehensive and widespread acute stage and rehabilitation services, it is important to develop a communication network between all levels of health care who receive SCI patients. Apart from allowing a complete assessment of the burden of SCIs in North Tanzania, it will also allow healthcare providers to identify the investment required in terms of infrastructure and personnel.

Our team’s involvement in this series of events serves to demonstrate that comprehensive spinal cord injury care remains challenging in a resource-limited setting and it is imperative that long-term planning to improve several aspects of care be undertaken.

Conclusion

The rehabilitation efforts of a team based in northern Tanzania are beset with challenges that are not uncommon in a low-resource setting. A unique combination of circumstances surrounds the injuries of our patients; a low socioeconomic background and an income based on agriculture which is a labour-intensive activity with returns dependent on climate conditions. These factors need to be taken into consideration at every step of treatment and rehabilitation of our patients. Widespread public awareness of injury prevention and effects may result in a reduced incidence and morbidity of TSCIs and should be explored.

References

World Health Organisation. International perspectives on spinal cord injury. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2013.

Reardon JM, Andrade L, Hetz J, Kiwango G, Teu A, Pesambili M, et al. The epidemiology and hotspots of road traffic injuries in Moshi, Tanzania: an observational study. Injury. 2017;48:1363–70.

Fisk N, Hulme-Moir I, Scrimgeour EM, Schlabach WE. Traumatic paraplegia in northern Tanzania. Trop Doct. 1985;15:23–26.

Rashid SM, Jusabani MA, Mandari FN, Dekker MC. The characteristics of traumatic spinal cord injuries at a referral hospital in Northern Tanzania. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2017;3:17021.

Moshi H, Sundelin G, Sahlen KG, Sörlin A. Traumatic spinal cord injury in the north-east Tanzania describing incidence, etiology and clinical outcomes retrospectively. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1355604.

Yatsuka H. Reconsidering the “indigenous peoples” in the African context from the perspective of current livelihood and its historical changes: the case of the Sandawe and the Hadza in Tanzania. Afr Stud Monogr. 2015;36:27–47.

Kirshblum SC, Waring W, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns SP, Johansen M, Schmidt-Read M, et al. Reference for the 2011 revision of the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;1:547–54.

Cripps RA, Lee BB, Wing P, Weerts E, Mackay J, Brown D. A global map for traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: towards a living data repository for injury prevention. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:493–501.

Otom AS, Doughan AM, Kawar JS, Hattar EZ. Traumatic spinal cord injuries in Jordan – an epidemiological study. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:253–5.

Witt A, Kumru H, Opisso E, Vidal J. Traumatic spinal cord injury due to human tower accident in Catolonia. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2018;4:108.

Macharia WM, Njeru EK, Muli-Musiime F, Nantulya V. Severe road traffic injuries in Kenya, quality of care and access. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9:118–24.

London JA, Mock CN, Quansah RE, Abantanga FA, Jurkovich GJ. Priorities for improving hospital-based trauma care in an African city. J Trauma. 2001;51:747–53.

Ahidjo KA, Olayinka SA, Ayokunle O, Mustapha AF, Sulaiman GA, Gbolahan AT. Prehospital transport of patients with spinal cord injury in Nigeria. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:308–11.

Netter F. Atlas of human anatomy. 6th edn. UK: Elsevier; 2014.

Hung DZ, Hung YH. Anticholinergics syndrome related to plants and herbs. Toxinology. 2015;2:569–86.

Stanifer JW, Patel UD, Karia F, Thielman N, Maro V, Shimbi D, et al. The determinants of traditional medicine use in northern Tanzania: a mixed-methods study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122638.

Dekker MCJ, Urasa SJ, Howlett WP. Neurological letter from Kilimanjaro. Pr Neurrol. 2017;5:412–6.

Feikin DR, Nguyen LM, Adazu K, Ombok M, Audi A, Slutsker L, et al. The impact of distance of residence from a peripheral health facility on pediatric health utilization in rural western Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14:54–61.

Bright T, Wallace S, Kuper H. A systematic review of access to rehabilitation for people with disabilities in low- and middle- income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:2165.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The case study was approved of by the Medical Ethics Committee of KCMC, Moshi, United Republic of Tanzania in the framework of a study on neurological disorders.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and their guardian.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Adrichem, D.C., Ratering, M.R.H.A., Rashid, S.M. et al. Penetrating spinal cord injury causing paraplegia in a bird hunter in rural Tanzania. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 5, 49 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0195-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0195-7

This article is cited by

-

Ox cart accidents as a cause of spinal cord injury in Tanzania

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2020)

-

Prehospital care of trauma patients in Tanzania: medical knowledge assessment and proposal for safe transportation of neurotrauma patients

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2020)