Abstract

Study design

A multi-centre online survey to staff working in specialised and non-specialised acute units.

Objectives

To identify clinical decisions and practices made for acute cervical spinal cord injury (CSCI) patients with respiratory impairments and oropharyngeal dysphagia.

Settings

All hospital intensive care units in the UK that admit acute cervical spinal cord injury patients.

Methods

Online distribution of a 35-question multiple-choice survey on the clinical management of ventilation, swallowing, nutrition, oral hygiene and communication for CSCI patients, to multi-disciplinary staff based in specialised and non-specialised intensive care units across UK.

Results

Responses were received from 219 staff members based in 92 hospitals. Of the 77 units that admitted CSCI patients, 152 participants worked in non-specialised and 30 in specialised units. Non-specialised unit staff showed variations in clinical decisions for respiratory management compared to specialised units with limited use of vital capacity measures and graduated weaning programme, reliance on coughing to indicate aspiration, inconsistent manipulation of tracheostomy cuffs for speech and swallowing and limited use of instrumental assessments of swallowing. Those in specialised units employed a multi-discplinary approach to clinical management of nutritional needs.

Conclusions

Variation in the clinical management of respiratory impairments and oropharyngeal dysphagia between specialised and non-specialised units have implications for patient outcomes and increase the risk of respiratory complications that impact mortality. The future development of clinical guidance is required to ensure best practice and consistent care across all units.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Demographics of SCI have changed in western countries from young men involved in high-velocity crashes towards older people with low-velocity falls [1]. This has led to increased rates of SCI at the cervical level [2] with associated paralysis of respiratory muscles and need for ventilatory support via tracheostomy. The disruption to respiratory mechanics and laryngeal function is linked to the disruption of normal swallowing function and oropharyngeal dysphagia, with a reported incidence of 30–40% increasing morbidity and mortality rates [3, 4].

In the UK, national guidance for ventilator weaning of CSCI patients was developed through consensus by a multi-professional group called Respiratory Information for Spinal Cord Injury (RISCI) [5]. This recommends a graduated process of respiratory weaning, using vital capacity (VC) as a key measure of respiratory fatigue. Periods of ventilator-free breathing will be determined based on VC with prescribed rest periods to limit fatigue due to retraining. Early gastrostomy is recommended for those who are likely to wean slowly and subglottic tracheostomy tubes support secretion clearance. Deflation of the tracheostomy cuff is encouraged to facilitate swallowing [6, 7] and speaking using a one-way valve, especially in the critical care environment. It is acknowledged that the weaning process can take an extended time with potential setbacks that demand a collaborative team approach. This guidance has been agreed and adopted by teams in specialised spinal units however it is not known whether staff in non-specialised units adhere to these recommendations. There is no specific guidance available on the clinical management of oropharyngeal dysphagia following CSCI.

The optimal management of respiratory, nutrition and swallowing problems requires involvement from multiple clinical professionals, including doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists and dietitians. The aim of this study was to explore the clinical practices of multi-disciplinary staff within specialised and non-specialised critical care units in the management of complex CSCI patients with respiratory and swallowing disorders. This information would highlight variations in care and help to contribute to future development of best practice recommendations to ensure consistent clinical management. This is the first study in a series of studies contributing to a doctoral investigation into the identification and management of oropharyngeal dysphagia in acute cervical spinal cord injury (DAISY project).

Methods

Owing to the absence of any pre-existing multi-disciplinary survey on the management of CSCI patients, a new survey was developed through a process of literature review to identify topic areas followed by survey construction and piloting with a representative group for validation.

Survey design and development

Topics for inclusion were derived from a review of the literature on oropharyngeal dysphagia, respiratory function, nutrition, oral care and communication in CSCI. A Medline search was performed using the terms “dysphagia”, “deglutition”, “ventilator weaning”, “tracheostomy”, “respiratory”, “enteral nutrition”, “oral hygiene” and “communication” each of which were paired with “spinal cord injury”, “cervical” and “tetraplegia”. Searches were limited to studies with human adults, written in English.

In devising the survey, multiple-choice questions were devised across five topic areas, with an option for free text comments. The topics were ventilator and tracheostomy weaning, nutritional decisions, dysphagia management, mouthcare and communication support.

A total of 35 questions were created across 22 pages with two additional free-text questions (see supplementary material). Adaptive questioning was used for two questions: grading differences between doctors, nurses and allied health professionals (AHPs) and mouthcare involvement. All professional groups were asked the same survey questions. The content and structure of the survey was evaluated by a steering group of representative multi-disciplinary professionals with expertise in acute SCI and amendments were made subject to their feedback.

Sample selection

Multi-professional respondents were sought from all critical care units in UK that admitted spinal cord injury patients, this included major trauma centres (MTC), district general hospitals (DGH), teaching hospitals (TCH), spinal injury units (SIU) and specialist hospitals (SPH) such as neurological or cardiothoracic units. Although it was expected that SCI patients would be admitted directly to one of 22 MTC, referrals to SIUs came from a broad range of hospitals, however it was not possible to identify all these units in advance. For this reason, purposive sampling was employed through email distribution to members of each critical care network and relevant professional bodies in UK. This included the Intensive Care Society, British Association of Critical Care Nurses (BACCN), Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT), British Dietetic Association (BDA) and The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) critical care groups. To increase recruitment of multi-professionals within and across units, snowball sampling was employed, whereby study participants were asked to invite other colleagues to respond to the survey.

Limited personal demographic details were collected, including profession, grade and hospital name, which was used to categorise unit type. Hospitals described as MTC, DGH and TCH were sub-categorised as non-specialised units as they did not specialise in SCI care, whereas SPH and SIU were considered specialised units, where the focus was only on SCI or neurological care.

Survey administration and analysis

The survey was launched in August 2014 and closed in January 2015. Responses were collected through an online web survey with results analysed using SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM) to generate descriptive data. This included the total number and percentage of responses per question and responses per hospital type. To explore variations in the care delivered to CSCI patients, responses were grouped into those from specialised and non-specialised hospitals. Responses from staff working in a SIU or SPH were grouped as specialised hospitals, while those responses from MTC, DGH and TCH were grouped as non-specialised hospitals (Table 1).

Results

Respondent demographics

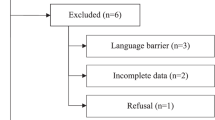

A total of 221 respondents participated in the survey (Fig. 1). Two overseas responses were excluded leaving a total of 219 multi-professional respondents from 92 units in UK. Respondent numbers varied across each hospital type and survey analysis was limited to 182 respondents from 77 units that admitted acute spinal cord injury patients, including eight spinal units in England, one from Scotland and one from Ireland, the remainder were excluded from survey completion. All five professional groups were represented in the responses from non-specialised units whereas specialised units lacked dietetic respondents. Medical respondents were senior and experienced while non-medical staff respondents represented a range of grades.

Clinical practices

These results focus on the clinical practices in the management of respiratory impairment, dysphagia, nutrition and communication for CSCI patients as reported by staff in non-specialised and specialised units. Owing to variations in group sizes, comparisons between units will be based on the typical practice reported.

Respondents from non-specialised units reported links to at least one spinal outreach team in England to access specialist advice and support. Eight respondents had links to spinal outreach teams in Glasgow or Dublin. Some respondents accessed more than one unit and five reported no known links to a spinal outreach service (Table 2).

Respiratory management of CSCI patients

Staff in specialised units utilised a number of methods to facilitate ventilator and tracheostomy weaning (Table 3). Vital capacity measures were routinely used to guide the respiratory weaning process, alongside cuff deflation, speaking valves and subglottic suction tubes, which were used less frequently by staff in non-specialised units. Routine tracheostomy capping prior to decannulation was strongly preferred by staff in specialised units. This forms the basis of the RISCI guidelines however few non-specialised unit staff used this guidance or outreach advice and some were uncertain about whether they used any guidance (Table 3).

Oropharyngeal dysphagia identification and management

Staff in specialised and non-specialised units reported the key signs of the presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in CSCI patients to be coughing, food suctioned from the tracheostomy with clinical symptoms being aspiration pneumonia, spiking pyrexia and wet sounding voice (Table 4). Methods for screening for oropharyngeal dysphagia involved monitoring saliva clearance, swallow trials with water and yoghurt. Staff also reported using blue dye and thickened fluids to test of swallowing. Routine swallow assessment used by Speech and Language Therapists was reported to be bedside swallow evaluations. The use of instrumental swallowing assessments, namely Fibreoptic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) and Videofluoroscopy (VFS), were reported as used more frequently by staff in specialised units (Table 4).

Speech and Language Therapists (SLT) are the staff members to manage oropharyngeal dysphagia in UK and approximately half of staff reported routine availability of SLT services. Referral to SLT was usually made after a positive nurse swallow screen test although aspiration pneumonia was a more frequent cause for referral by staff in specialised units. With some debate about patients eating with tracheostomy cuff inflated, this was reported as happening either routinely or sometimes by staff in non-specialised units whereas staff in specialised unit only allowed cuff up eating occasionally (Table 4).

Nutritional management

Staff at specialised and non-specialised units agreed on similar criteria for determining the need for non-oral feeding (Table 5). Having a tracheostomy in situ was reported more by staff in non-specialised units. The decision to transition to long term gastrostomy feeding tubes differed between units, staff in specialised units adhered to recommendations by SLT and dietitians, whereas staff in non-specialised units based their decisions on whether swallowing problems were ongoing (Table 5). Staff relied on repeat swallow assessments to determine whether a patient was safe to return to oral intake.

Communication

Overall, staff at both specialised and non-specialised units tended to use low-technology methods to facilitate patients’ ability to communicate, with advice given to patients and families and encouragement to use mouthing to help express themselves. High-technology aids were not used as frequently, as physical access is limited. Using cuff deflation to allow leak speech was more consistently employed by specialised unit staff along with in-line speaking valves (Table 6).

Discussion

This is the first exploratory study to investigate the clinical care of respiratory dysfunction, oropharyngeal dysphagia and nutrition in CSCI patients within specialised and non-specialised units across the UK. Systematic reviews of the care provision in SIUs support early admissions both to prevent complications and improve outcomes [8, 9]. Deteriorating respiratory function is frequently cited as a key complication with pneumonia contributing to mortality [10, 11]. Oropharyngeal dysphagia increases the risk of aspiration pneumonia, which is likely to add burden to existing respiratory dysfunction [12, 13]. The need for this study was based on the increasing delays to admission to specialised units, particularly for those with cervical level injuries and associated respiratory requirements. This is contrary to the nationally set algorithm for acute SCI care, suggesting prompt transfer to a specialised unit following an MTC admission in order to access the required specialist interventions [14]. A recent report has identified increasing demand and limited bed capacity in specialised units resulting in CSCI patients remaining in non-specialised units for prolonged acute care [15]. In the absence of clinical guidance, this survey aimed to identify clinical practices that have an impact on patient outcomes and would benefit from clear clinical guidance.

The evidence for the pathophysiology of oropharyngeal dysphagia following CSCI is unclear as studies are largely observational and retrospective. Respiratory, neurological and mechanical disruption to the cervical region appear to contribute to laryngeal dysfunction. Early case series reported links to dysphagia although the causes were unclear. Pollock et al. [16] reported four cases of unexpected pharyngeal damage post cervical trauma, while Grundy et al. [17] highlighted the presence of ‘bulbar palsy, with acute respiratory distress and dysphagia’’ in eight patients with cervical injuries. In a larger review, Hsu et al. [18] identified 47 cases of glottis or tracheal stenosis over a 20-year period, causing dysphagia, dysphonia and excessive secretions. Although the cranial nerves in the brainstem innervate many facial and laryngeal functions, there is evidence for anastomoses with the cervical spinal nerves creating a cervical plexus [19]. The ansa cervicalis provides motor innervation to the muscles control hyoid function, essential for swallowing and speech [20]. Fibres of the hypoglossal nerve also join the ansa cervicalis to innervate part of the tongue. The variability in the location of these structures may partially explain the loss of swallow function following CSCI [21].

The loss of phrenic nerve function with injuries above C5, interrupts normal breathing patterns and paralyses the diaphragm. Swallowing function is closely coordinated with the breathing cycle and disruption leads to accidental inhalation and aspiration during the swallow, with lack of cough preventing airway clearance [22]. Respiratory interventions including tracheostomy insertion and supported ventilation are known to cause additional disruption to swallowing and are frequently cited as factors linked to dysphagia following CSCI [3, 4, 23,24,25,26].

Cervical spinal surgery is often indicated for traumatic injuries and much of the evidence from elective surgery cohorts report both dysphagia and dysphonia as common post-operative complications often due to pharyngeal wall oedema and nerve injury due to retraction time [27,28,29], with both posterior and anterior approaches demonstrating neurological impact on swallowing function [30].

Gastrointestinal functions are often affected following CSCI due to the loss of autonomic control, leading to dysmotility and paralytic ileus, often requiring aspiration of gastric contents [31]. This adds another level of challenge for patients identified with dysphagia as alternative routes of nutrition need to be considered. High malnutrition rates have been reported in SCI populations admitted to specialised units in England [32] of which CSCI and tracheostomy patients were the largest cohort. Decisions about early nutritional support appear to be inconsistent and rely on a wait-and-see approach and evidence of prolonged oropharyngeal dysphagia rather than pro-active management.

The combination of respiratory, swallowing and gastrointestinal impairment increases the risk of aspiration and staff need to be aware of the signs in order to prevent symptoms developing, which can be difficult to reverse. The survey results demonstrate variations in care that can have an impact on these functions and the negative consequences of dysphagia. A graduated weaning approach, utilising vital capacity as a clinical measure, has been recommended for CSCI patients through expert consensus and adopted by the Intensive Care Society [5], however, this is not routinely used by staff in non-specialised units.

Accurate evaluation of laryngeal dysfunction helps the weaning process and permits more options for verbal communication, which is important for intensive care patients [33]. Currently there is little guidance to direct staff on optimal management of tracheostomy [34] or dysphagia and some methods described by staff may put patients at increased risk of aspiration pneumonia, dehydration and mortality [35, 36]. This includes the use of thickened fluids for patients with dysphagia, on the premise that increased viscosity slows transit of the fluid allowing more time for a delayed swallow initiation to capture the bolus. In contrast, the key feature of dysphagia in CSCI patients is not delayed swallowing but ineffective pharyngeal squeeze [26] making thickened fluids unsuitable as they are more challenging to clear from the pharynx and can increase damage to lung mucosa due to aspiration [37]. Similarly, a reliance on the cough reflex to signify aspiration is problematic especially for patients with inflated tracheostomy cuffs [38] or absent cough ability due to impairment to the vagus nerve [39]. Instead, instrumental assessments, such as FEES or VFS are recommended to identify laryngeal impairments that are asymptomatic at bedside [3, 23, 24, 26, 40].

As with many surveys, there were limitations to using this method of evaluating current practice. Recruitment of multi-professional staff in specialised and non-specialised units relied on purposive and snowball sampling, making a response rate difficult to calculate. However, responses from staff at a large number of units across UK did reveal the widespread transfer of SCI patients from trauma units to non-specialised units, which does not fulfil the national service specification for acute SCI management and this would benefit from further investigation and analysis of the national database. Sample sizes for each group varied considerably making statistical comparisons inappropriate, instead the results provide qualitative data and insight into current practices, which have not previously been identified. Some professional groups were less well represented and staff reported that they had little disease-specific training and expertise with this patient group, despite having to deliver care. This may have had an impact on the survey completion rate with a loss of just over a third (35%) of respondents. A follow-up study may consider profession specific questionnaires or interviews, to explore practices in more detail.

The incidence of CSCI are increasing nationally [1, 41] and are often associated with respiratory dysfunction and oropharyngeal dysphagia [42]. With limited bed availability in specialised units in UK, these patients remain in non-specialised units for management of these impairments. This survey highlighted variations in clinical practice in the absence of national guidance, which have an impact on clinical outcomes. With no plans to increase respiratory bed capacity in specialised units, clinical guidance is required to support multi-disciplinary teams to deliver safe and consistent care. Further research is needed to capture the clinical outcomes for CSCI patients managed in specialised and non-specialised units.

Disclaimer

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and Health Education England. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

McCaughey EJ, Purcell M, McLean AN, Fraser MH, Bewick A, Borotkanics RJ, et al. Changing demographics of spinal cord injury over a 20-year period: a longitudinal population-based study in Scotland. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:270–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.167. 2015/10/16.

Singh A, Tetreault L, Kalsi-Ryan S, Nouri A, Fehlings MG. Global prevalence and incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:309–31. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S68889.

Chaw E, Shem K, Castillo K, Wong SL, Chang J. Dysphagia and associated respiratory considerations in cervical spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2012;18:291–9. https://doi.org/10.1310/sci1804-291.

Shem K, Castillo K, Wong SL, Chang J, Kolakowsky-Hayner S. Dysphagia and respiratory care in individuals with tetraplegia: incidence, associated factors, and preventable complications. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2012;18:15–22. https://doi.org/10.1310/sci1801-15. 2012/01/01.

Respiratory Information for Spinal Cord Injury R. Weaning guidelines for spinal cord injury patients in critical care units, http://risci.org.uk/weaning-guidelines-for-spinal-cord-injured-patients-in-critical-care-units/. 2012 (Accessed 4th August 2015).

Ding R, Logemann JA. Swallow physiology in patients with trach cuff inflated or deflated: a retrospective study. Head Neck. 2005;27:809–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20248. 2005/08/09.

Pryor L, Ward E, Cornwell P, O’Connor S, Chapman M. Patterns of return to oral intake and decannulation post-tracheostomy across clinical populations in an acute inpatient setting. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2016;51:556–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12231. 2016/02/20.

Maharaj MM, Hogan JA, Phan K, Mobbs RJ. The role of specialist units to provide focused care and complication avoidance following traumatic spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:1813–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4545-x. 2016/04/03.

Parent S, Barchi S, LeBreton M, Casha S, Fehlings MG. The impact of specialized centers of care for spinal cord injury on length of stay, complications, and mortality: a systematic review of the literature. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:1363–70. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2009.1151. 2011/03/18.

Osterthun R, Post MW, van Asbeck FW, van Leeuwen CM, van Koppenhagen CF. Causes of death following spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation and the first five years after discharge. A Dutch cohort study. Spinal Cord. 2014;52:483–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.28.

Martin ND, Marks JA, Donohue J, Giordano C, Cohen MJ, Weinstein MS. The mortality inflection point for age and acute cervical spinal cord injury. J Trauma. 2011;71:380–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e318228221f.

Winslow C, Bode RK, Felton D, Chen D, Meyer PR. Impact of respiratory complications on length of stay and hospital costs in acute cervical spine injury. Chest. 2002;121:1548–54.

Berlly M, Shem K. Respiratory management during the first five days after spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:309–18. 2007/09/15.

CRG for Spinal Cord Injury. The initial management of adults with spinal cord injuries: advice for major trauma networks https://www.rnoh.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/advice_for_acute_centres_on_acute_sci_in_adults.pdf. 2016 (Accessed 20th March 2016).

Spinal Injuries Association. A paralysed system?. Spinal Injuries Association. https://www.spinal.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/SIA-APP-Paralysed-System-Report-FINAL-lores.pdf. 2015. (Accessed 18th July 2015).

Pollock RA, Purvis JM, Apple DF Jr., Murray HH. Esophageal and hypopharyngeal injuries in patients with cervical spine trauma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981;90:323–7. 1981/07/01.

Grundy DJ, McSweeney T, Jones HW. Cranial nerve palsies in cervical injuries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1984;9:339–43. 1984/05/01.

Hsu S, Dreisbach JN, Charlifue SW, English GM. Glottic and tracheal stenosis in spinal cord injured patients. Paraplegia. 1987;25:136–48. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.1987.23.

Shoja MM, Oyesiku NM, Shokouhi G, Griessenauer CJ, Chern JJ, Rizk EB, et al. Anastomoses between lower cranial and upper cervical nerves: A comprehensive review with potential significance during skull base and neck operations, part II: Glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory, and hypoglossal nerves and cervical spinal nerves 1–4. Clin Anat. 2014;27:131–44.

Loukas M, Thorsell A, Tubbs RS, Kapos T, Louis RG Jr., Vulis M, et al. The ansa cervicalis revisited. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2007;66:120–5. 2007/06/28.

Mwachaka PM, Ranketi SS, Elbusaidy H, Ogeng’o J. Variations in the anatomy of ansa cervicalis. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2010;69:160–3. 2010/12/15.

Hadjikoutis S, Pickersgill TP, Dawson K, Wiles CM. Abnormal patterns of breathing during swallowing in neurological disorders. Brain. 2000;123:1863–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/123.9.1863.

Kirshblum S, Johnston MV, Brown J, O’Connor K, Jarosz P. Predictors of dysphagia after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1101–5.

Brady S, Miserendino R, Statkus D, Springer T, Hakel M, Stambolis V. Predictors to dysphagia and recovery after cervical spinal cord injury during acute rehabilitation. J Appl Res. 2004;4:1–11.

Seidl RO, Nusser-Muller-Busch R, Kurzweil M, Niedeggen A. Dysphagia in acute tetraplegics: a retrospective study. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:197–201. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.102.

Shin JC, Yoo JH, Lee YS, Goo HR, Kim DH. Dysphagia in cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:1008–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.34. 2011/05/18.

Joaquim AF, Murar J, Savage JW, Patel AA. Dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a systematic review of potential preventative measures. Spine J. 2014;14:2246–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2014.03.030. 2014/03/26.

Leonard R, Belafsky P. Dysphagia following cervical spine surgery with anterior instrumentation: evidence from fluoroscopic swallow studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36:2217–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e318205a1a7. 2011/02/18.

Papavero L, Heese O, Klotz-Regener V, Buchalla R, Schroder F, Westphal M. The impact of esophagus retraction on early dysphagia after anterior cervical surgery: does a correlation exist? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:1089–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000261627.04944.cf. 2007/05/02.

Smith-Hammond CA, New KC, Pietrobon R, Curtis DJ, Scharver CH, Turner DA. Prospective analysis of incidence and risk factors of dysphagia in spine surgery patients: comparison of anterior cervical, posterior cervical, and lumbar procedures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:1441–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000129100.59913.ea. 2004/06/30.

Chung EAL, Emmanuel AV. Gastrointestinal symptoms related to autonomic dysfunction following spinal cord injury. Prog Brain Res. 2006;152:317–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(05)52021-1.

Wong S, Derry F, Jamous A, Hirani SP, Grimble G, Forbes A. The prevalence of malnutrition in spinal cord injuries patients: a UK multicentre study. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:918–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114511006234. 2011/12/17.

Cameron TS, McKinstry A, Burt SK, Howard ME, Bellomo R, Brown DJ, et al. Outcomes of patients with spinal cord injury before and after introduction of an interdisciplinary tracheostomy team. Crit Care Resusc. 2009;11:14–19.

Pryor LN, Ward EC, Cornwell PL, O’Connor SN, Chapman MJ. Clinical indicators associated with successful tracheostomy cuff deflation. Australian Crit Care. 2016;29:132–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2016.01.002.

Robbins J, Gensler G, Hind J, Logemann JA, Lindblad AS, Brandt D, et al. Comparison of 2 interventions for liquid aspiration on pneumonia incidence. Ann Int Med. 2008;148:509–18.

Cichero JAY. Thickening agents used for dysphagia management: effect on bioavailability of water, medication and feelings of satiety. Nutr J. 2013;12:54.

Nativ-Zeltzer N, Kuhn MA, Imai DM, Traslavina RP, Domer AS, Litts JK, et al. The effects of aspirated thickened water on survival and pulmonary injury in a rabbit model. Laryngoscope. 2018;128:327–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26698. 2017/07/22.

Goff D, Patterson J. Eating and drinking with an inflated tracheostomy cuff: a systematic review of the aspiration risk. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2019;54:30–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12430.

Valenzano TJ, Waito AA, Steele CM. A review of dysphagia presentation and intervention following traumatic spinalinjury: An understudied population. Dysphagia. 2016;31:598–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-016-9728-4.

Wolf C, Meiners TH. Dysphagia in patients with acute cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2003;41:347–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101440. 2003/05/15.

Devivo MJ. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury: trends and future implications. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:365–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.178.

Ihalainen T, Rinta-Kiikka I, Luoto TM, Koskinen EA, Korpijaakko-Huuhka AM, et al. Traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: a prospective clinical study of laryngeal penetration and aspiration. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:979 https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.71.

Author contributions

JM conceived the study, acquired the data, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. AE, CS and SB revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

Jackie McRae was funded by a National Institute of Health Research and Health Education England Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship. Anton Emmanuel was supported by the UCL Biomedical Research Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical committee approval was received through Stanmore Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 14.LO.1209) and NHS R&D as part of the doctoral study (JM) (IRAS: 129588).

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41394_2019_175_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Respiratory Information for Spinal Cord Injury UK (RISCI) weaning guidelines for spinal cord injured patients in critical care units

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McRae, J., Smith, C., Beeke, S. et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia management in cervical spinal cord injury patients: an exploratory survey of variations to care across specialised and non-specialised units. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 5, 31 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0175-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0175-y

This article is cited by

-

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Acute Cervical Spinal Cord Injury: A Literature Review

Dysphagia (2023)

-

Videofluoroscopic Profiles of Swallowing and Airway Protection Post-traumatic Cervical Spinal Cord Injury

Dysphagia (2022)

-

The experiences of individuals with cervical spinal cord injury and their family during post-injury care in non-specialised and specialised units in UK

BMC Health Services Research (2020)