Abstract

Introduction

Patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) and concomitant lower limb fractures are a challenge to rehabilitate. Conventionally, postural orientation is an important milestone in the rehabilitative process. We propose an alternative strategy in achieving goals in individuals with an SCI with concomitant injuries that preclude weight bearing below the knee.

Case presentation

A 16-year-old girl sustained a burst fracture of L1 in conjunction with bilateral ankle fractures. During rehabilitation, the calcaneal fracture on the left and tibial plafond fracture on the right prevented her progression in conventional rehabilitation. An alternative strategy “K-ing” (Kneel Standing/Kneel Walking) was adopted to facilitate truncal activation without loading the ankle joints. This was found to be helpful in obtaining upright posture stability without hampering her recovery of associated ankle injuries.

Discussion

“K-ing” strategy can be useful and presents a simple alternative in the presence of associated ankle injuries. It also avoids complications associated with bedrest when there is delay in initiation of ambulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gait training in individuals with an SCI is challenging to patients and physical therapists. The possible comorbidities in the progression of rehabilitation in these cases are postural hypotension [1], heterotrophic ossification [2], and other concomitant injuries like lower-extremity fractures [3, 4]. The incidence of lumbar spine injuries in calcaneal fractures has been reported to be 80% [5]. In the rehabilitation process, bipedal loading is an integral part [6, 7] prior to ambulation training. The associated lower-extremity fractures can be a setback in individuals with an SCI, which can always pose a threat in achieving standing balance and gait training [8, 9]. The objective of this case report is to present a low-cost rehabilitation strategy that can be performed without loading the fractured lower limbs and help achieve functional goals.

Case presentation

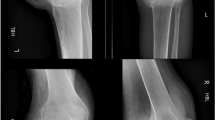

A 16-year-old girl sustained an L1 fracture and bilateral fractures involving foot and ankle (left calcaneum and right tibial plafond). The clinical presentation was AIS A paraplegia with the absence of sensation below T10 and loss of motor power below T12 along with loss of bladder and bowel sensation. She was treated surgically with decompression and posterior stabilization with pedicle screws and rods. Fracture of the tibial plafond was managed by closed reduction and below-knee plaster-of-paris cast application. Fracture of the calcaneus was treated by closed reduction followed by below-knee plaster-of-paris cast application. The patient was transferred to rehabilitation at the end of the first week following surgery.

The initial assessment of the neurological level of injury postoperatively remained T10 AIS A [10]. The manual muscle test (MMT) was grade zero in all the muscles of both the lower limbs. The motor index score was 50 of 100, while the sensory index score was 68 of 112. Our postoperative spinal stabilization physiotherapy protocol was followed for the first week (Table 1). The individual progressed to sitting upright by the end of the second week using a spinal hyperextension support (ASH Brace). Electrical stimulation to the knee extensors and flexors with galvanic currents (30 contractions—3 sets/day) was provided [11, 12]. At the end of 5 weeks, a trace of contraction was noted in the left quadriceps with muscle power grade 1 (MMT).

Although the Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence guidelines indicate that standing in a tilt table or in the parallel bars is a recommended therapy at the end of 4–6 weeks [13], this is to be done only if the individual does not have an associated lower limb fracture. Since the calcaneal [14] and tibial plafond fractures [15] prevented this individual from loading through the feet, physician clearance was obtained to progress the subject to quadruped positioning. The objective was to obtain static balance training to enhance trunk stability with loading through the femurs. Medical clearance was also given to progress to quadruped crawling. Once quadruped balance was achieved for 2–5 min, during weeks 2through 4, crawling was initiated. This facilitated the progression to kneel standing with support on a cushioned mat and later in the parallel bars with adequate cushion support in order to avoid skin complications.

At 3 months post injury, static kneeling was achieved for 3–5 min at 2 months and kneel walking was initiated afterward. Initially, kneel walking was introduced gradually with pillows over the knee with height adjusted in the parallel bars to accommodate the lower trunk alignment (Fig. 1). The progression started with 3–5 min twice a day and increased to 10–12 min twice a day as tolerated. At the end of 3 months, kneeling balance with the cushion was achieved for about 8–10 min and kneel walking inside the parallel bars for (10–15 steps) × 2 was achieved. Subsequently, loading started in the bilateral lower limb as the fracture union was radiologically confirmed. Bilateral knee ankle foot orthoses (KAFO) were fabricated to allow standing balance training and ambulation progression. The participant was made to stand inside the parallel bars for 2–5 min for a few days and the standing duration was increased gradually to 5–10 min. As the standing balance improved, walking was initiated. Within a week, walking inside parallel bars was achieved for about (5–10 steps) × 2/day (Fig. 2).

During initial assessment, there was a complete loss of sensation below T10 and the predischarge examination at 3 months post injury revealed a partial return of sensation from T10 to S1 on the right and from T10 to S3 on the left. The sensory index score was 87 out of 112. There was a partial recovery of muscle power in lower limb key muscles [Hip flexors (from 0/5 to 3/5 bilateral) and knee extensors (from 0/5 to 2/5 bilateral)]. The motor index score was 60 out of 100. Even though the individual showed partial return of motor and sensory functions in the lower limbs, there was no gain in deep anal pressure and thus remained as AIS A type of injury at the time of discharge (Table 2).

The walking index for spinal cord injury was used to measure her outcome ambulation score. She obtained a score of 7 (ambulates with two crutches, with braces and physical assistance of one person, 10 meters) at the end of 4 months [16].

Discussion

This case report describes the K-ing strategy used in early mobilization on a participant with cauda equina injury and bilateral foot and ankle injury. Studies indicate that early mobilization reduces postoperative complications and provides physiological and psychological benefits [1, 2]. Early vertical loading can promote balance and ambulation training in a SCI rehabilitation program [5,6,7, 17,18,19,20].

The K-ing strategy can be a safe alternative in promoting vertical orientation [21, 22] without loading the leg and foot component and simultaneously preserving the fracture sites. Since the kneel standing and kneel walking re-education simulated standing and walking respectively, this might also have been a positive effect on improving motor function. In SCI rehabilitation, loading the hip joint is a critical stimulus in the process of re-innervation of muscles concerned with locomotor training [23,24,25]. Hence, this strategy could be a crucial intervention in promoting postural orientation despite the comorbidities.

Hip extension [26] is crucial in achieving standing balance in SCI rehabilitation. In this case, K-ing strategy facilitated hip extension by loading through femurs when bipedal stance could not be allowed. Bipedal stance and ambulatory training with orthotic support may be achieved by 8–12 weeks. In this case, bipedal stance had to be delayed due to the associated lower limb fractures, thereby resulting in a possible delay of another 4–6 weeks. Introducing this alternative strategy in early mobilization to an upright position may have reduced the length of stay and therefore the cost of hospitalization [27].

Conclusion

“K-ing strategy” may be useful for progression to ambulation in SCI patients associated with foot and ankle fractures. This technique may also have a positive effect on neural activation and prevent the deleterious effects of prolonged inactivity. Further studies are required to validate if “K-ing strategy” ambulation outcomes are similar to or more effective than other conventional interventions in SCI patients.

References

Nas K, Yazmalar L, Sah V, Aydin A, Ones K. Rehabilitation of spinal cord injuries. World J Orthop. 2015;6:8–16.

Ragnarsson KT. Medical rehabilitation of people with spinal cord injury during 40 years of academic physiatric practice. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91:231–42.

Carbone LD, Chin AS, Burns SP, Svircev JN, Hoenig H, Heggeness M, et al. Morbidity following lower extremity fractures in men with spinal cord injury. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2261–7.

Frotzler A, Cheikh-Sarraf B, Pourtehrani M, Krebs J, Lippuner K. Long-bone fractures in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2015;53:701–4.

Walters JL, Gangopadhyay P, Malay DS. Association of calcaneal and spinal fractures. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53:279–81.

Harkema SJ, Hillyer J, Schmidt-Read M, Ardolino E, Sisto SA, Behrman AL. Locomotor training: as a treatment of spinal cord injury and in the progression of neurologic rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:1588–97.

Dietz V, Harkema SJ. Locomotor activity in spinal cord-injured persons. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1954–60.

Krajacic A, Ghosh M, Puentes R, Pearse DD, Fouad K. Advantages of delaying the onset of rehabilitative reaching training in rats with incomplete spinal cord injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:641–51.

Wrigley PJ, Gustin SM, Macey PM, Nash PG, Gandevia SC, Macefield VG, et al. Anatomical changes in human motor cortex and motor pathways following complete thoracic spinal cord injury. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:224–32.

Roberts TT, Leonard GR, Cepela DJ. Classifications in brief: American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) impairment scale. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:1499–504.

de Freitas GR, Santo C, de Machado-Pereira N, Bobinski F, Dos Santos ARS, Ilha J. Early cyclical neuromuscular electrical stimulation improves strength and trophism by akt pathway signaling in partially paralyzed biceps muscle after spinal cord injury in rats. Phys Ther. 2018;98:172–81.

Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, Brodke DS, et al. A clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with acute spinal cord injury: recommendations on the type and timing of rehabilitation. Global Spine J. 2017;7(3 Suppl):231s–8s.

Eng JJ, Teasell R, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Aubut JA, et al. Spinal cord injury rehabilitation evidence: methods of the SCIRE systematic review. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2007;13:1–10.

Yang Y, Zhao H, Zhou J, Yu G. Treatment of displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures with or without bone grafts: a systematic review of the literature. Indian J Orthop. 2012;46:130–7.

Marsh JL, McKinley T, Dirschl D, Pick A, Haft G, Anderson DD, et al. The sequential recovery of health status after tibial plafond fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:499–504.

Menon N, Gupta A, Khanna M, Taly AB. Ambulation following spinal cord injury and its correlates. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2015;18:167–70.

Driver S, Warren AM, Reynolds M, Agtarap S, Hamilton R, Trost Z, et al. Identifying predictors of resilience at inpatient and 3-month post-spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39:77–84.

Drigotaite N, Krisciunas A. [Complications after spinal cord injuries and their influence on the effectiveness of rehabilitation]. Medicina. 2006;42:877–80.

Madsen UR, Hommel A, Berthelsen CB, Baath C. Systematic review describing the effect of early mobilisation after dysvascular major lower limb amputations. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:3286–97.

Harvey L. Management of spinal cord injuries. London: Elsevier; 2008.

Gallagher S. Trunk extension strength and muscle activity in standing and kneeling postures. Spine. 1997;22:1864–72.

Ulbrich J, Raheja A, Alexander NB. Body positions used by healthy and frail older adults to rise from the floor. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1626–32.

Edgerton VR, Tillakaratne NJ, Bigbee AJ, de Leon RD, Roy RR. Plasticity of the spinal neural circuitry after injury. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:145–67.

Dietz VG. Heiner Sell memorial lecture: neuronal plasticity after spinal cord injury: significance for present and future treatments. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29:481–8.

Roy RR, Harkema SJ, Edgerton VR. Basic concepts of activity-based interventions for improved recovery of motor function after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:1487–97.

Behrman AL, Bowden MG, Nair PM. Neuroplasticity after spinal cord injury and training: an emerging paradigm shift in rehabilitation and walking recovery. Phys Ther. 2006;86:1406–25.

Truchon C, Fallah N, Santos A, Vachon J, Noonan VK, Cheng CL. Impact of therapy on recovery during rehabilitation in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:2901–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jagadevan, M., Mohanakrishnan, B., Murugesan, S. et al. Progression to ambulation following lower limb fractures in an individual with a spinal cord injury: a case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 5, 26 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0171-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0171-2