Abstract

Study design

Exploratory qualitative study using photo-elicitation interviews.

Objectives

To identify contributors to falls, as perceived by individuals with incomplete spinal cord injury, and describe the impact of perceived fall risk on mobility and physical activity.

Setting

Participants’ home and community environments.

Methods

Eight individuals with chronic motor incomplete spinal cord injury participated. Participants took photographs of situations that increased/decreased their risk of falling, or depicted how this risk impacted mobility and physical activity. Photographs were discussed in semi-structured interviews. Inductive thematic analysis was used to describe participants’ perceptions and experiences.

Results

Photo-elicitation interviews identified four themes: (1) Perceived challenges were primarily environmental with biological (e.g., reduced strength) and behavioral (e.g., risk-taking) factors also identified. (2) Impact of perceived fall risk included moving slowly, avoiding balance-provoking activities, and feelings of frustration and/or fear. (3) Prevent falls: learn through experience included strategies used to avoid falls, which were learnt experientially and consisted of changes to behavior. (4) Factors mitigating impact of perceived fall risk included character traits (i.e., perseverance, optimism) and a desire for independence.

Conclusions

Primarily environmental factors were perceived to contribute to fall risk and mainly behavioral strategies were adopted to mitigate the risk.

Sponsorship

Physiotherapy Foundation of Canada.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Falls are prevalent among individuals living with spinal cord injury (SCI). This is especially true for the incomplete SCI (iSCI) population, which includes individuals who have some sparing of sensorimotor function below the neurological level of injury. Within a year about 75% of those with an iSCI will experience a fall [1]; most commonly while walking [1,2,3]. A fall can result in many adverse consequences for people with SCI. Bruising and skin abrasions are the most common physical injuries [3], however, 27% of injuries are sufficiently serious to warrant hospital readmission [4], resulting in increased attendant care and health care costs [4, 5]. In addition to physical injuries, those who fall may experience a “post-fall syndrome” characterized by dependence, reduced mobility, loss of autonomy, depression, and restricted participation in daily activities [6].

Despite the high risk of falling, few studies have sought to characterize the causes of falls among people with SCI [1, 3, 4]. Among ambulatory individuals with SCI, most falls occur while walking in the home or workplace, followed by transitioning between different postures (e.g., sit to stand) [3, 7, 8]. Two common reasons for falls are a “loss of balance” and “environmental hazards” [9]. Previous work has identified “obstacle[s] on the floor” [9] and “door swills, carpets, stairs, hills, uneven ground, darkness, and moving in crowds” [10] as potential hazards. Less research has focused on the causes of falls involving individuals with SCI who use a wheelchair as their main means of mobility [11]. Falls for this group often occur during transferring, propelling, and reaching [12].

The majority of the information about falls after SCI has been collected through surveys or structured interviews [1, 2, 7, 8, 13, 14], which limits the depth and breadth of the information that can be collected [15]. To our knowledge, only one study has used semi-structured interviews to capture details about falls in individuals with iSCI [10]. Compared with surveys and interviews, photo-elicitation interviews (PEI) may enable more detailed insight into the fall-related issues considered important by individuals with iSCI. With PEI, participants take photographs of situations, places, people, or things that are meaningful to them, and the photographs are then used to elicit narratives on the topic(s) of interest [16, 17]. Through PEI participants are actively involved in data collection [16]. Individuals with SCI have described this type of participatory research as providing them with “revelations” regarding the adaptations they utilize to overcome challenges [18]; hence, participatory research methods, such as PEI, may provide participants the opportunity to identify solutions to the issue being discussed [16]. By including individuals with iSCI in the research process, our understanding of the causes and consequences of falls among this group can be enhanced. This information will inform rehabilitation practice and create opportunities for enhancing fall prevention initiatives that are client-driven [18]. Hence, we used PEI to (1) identify the factors that contribute to falls, as perceived by individuals with iSCI, and (2) describe the perceived impact of fall risk on individuals with iSCI, with an emphasis on mobility and participation in physical activity.

Methods

This was an exploratory, qualitative study. Data collection spanned March through June in two Canadian provinces. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Boards of the University Health Network in Toronto and the University of Saskatchewan. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Participants

Participants were recruited through flyers posted within the Lyndhurst Centre—Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, Spinal Cord Injury Ontario, and the University of Saskatchewan. The target sample size, 7–10 participants, was based on the number of participants recommended for qualitative research combining interviews and photographs [19, 20]. To participate, individuals were required to meet the following criteria: (1) sustained a traumatic or non-traumatic iSCI that is motor incomplete (i.e., American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) C or D), (2) be at least 6 months post-injury, (3) live in the community, (4) report having experienced at least one fall in the past 6 months, with a fall defined as “an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level” [21], (5) be at least 18 years of age, and (6) have no other significant co-morbid condition that could affect mobility or physical activity, such as an acquired brain injury, vestibular disorder or cancer. Demographic information, injury-related data, and ambulatory status (i.e., ambulator or wheelchair user) were collected during the screening process.

Study procedures

Each participant completed the following procedures in the listed order over 8–10 days:

(1) Clinical Assessment: For descriptive purposes, two clinical measures were administered by a researcher with a background in physical therapy (KL or KEM). The Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury II (WISCI II) is a 21-point ordinal scale that rates one’s ability to walk ten meters [22, 23]. The rating is dependent on the devices, braces, and physical assistance required by the participant [22, 23]. The Mini-Balance Evaluation Systems Test (mini-BESTest) is a 14-item scale that assesses four aspects of balance control: anticipatory postural adjustments, reactive postural control, sensory orientation, and dynamic gait [24, 25].

(2) Photo-taking: Immediately following the clinical assessment, participants were oriented to the purpose and method of photo-elicitation. Each participant was given a digital camera, instructed in its use, and informed of the privacy and ethical aspects of photography. For example, they were asked not to take pictures of anyone under the age of 18 years. Participants were asked to take at least two photographs for each of the following questions over 7 days (i.e., photo assignment): (1) What increases your likelihood of falling? (2) What decreases your likelihood of falling? (3) How does the risk of falling affect your mobility and physical activity? At the end of the 7 days, participants would have taken a minimum of six photographs. If participants chose to include another adult in a picture, they were asked to obtain consent for inclusion of this individual’s image through use of a third party photo release form. If a participant had difficulty holding and manipulating a camera, adaptations were offered (e.g., small tripods, neck straps). Participants were also told they could have a caregiver or friend assist with the photo-taking.

(3) PEI Interviews: Within one week of photo-taking, a semi-structured, individual, in-person interview was conducted by a single researcher (KEM). At the interview, participants discussed a total of 6–9 of their photographs (i.e., 2–3 photographs per photo assignment question mentioned above), as well as the reasons why they chose to capture these images. Participants chose the 6–9 photographs that they wished to discuss. The target of 6–9 photographs was based on the time allocated for the interviews (i.e., 1 h) and the length of time required to discuss each photograph (i.e., 5–10 min). The interview questions followed the SHOWeD framework [19]. They were asked to describe what is happening in the photo, why they think the situation exists, and what can be done about it [19]. The researcher also asked a few open-ended questions concerning the participant’s experience with fall prevention education and training. The interview was digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim offline by the Social Sciences Research Laboratories at the University of Saskatchewan. Following transcription, each participant was asked to review their transcript and indicate whether it was an accurate reflection of the interview, and whether they would like to add or delete any information in the transcript (i.e., member check) [26].

Data analysis

Transcribed dialog from the interviews was imported into NVivo 11 (QSR International Pty Ltd., Burlington, MA) for data management, coding, and analysis. An inductive thematic analysis was used to identify the key messages that described the participants’ perceptions and experiences. First, two researchers (KEM and CP) independently reviewed two transcripts thought to contain the most information. They took note of the ideas and terms reflecting the content of the text, and then jointly developed a coding scheme (i.e., codes with definitions). The coding scheme was discussed with two other researchers (CA and SO) who had also read the transcripts. New codes were added or definitions of codes refined based on these discussions. The resulting coding scheme was then applied to the remaining interviews by KEM and CP, with further refinement of codes and code definitions. Lastly, the researchers grouped the identified codes into larger categories, and subsequently grouped these categories into overarching themes.

Results

Nine individuals with iSCI volunteered to participate. One was excluded as he had not experienced a fall in the past 6 months. Thus, eight individuals with iSCI participated (six male, two female, 48.9 ± 14.9 years old, 3 AIS C, 5 AIS D) (Table 1). Four participants used a wheelchair as their main means of mobility (WISCI II scores ranged 0–13). The remaining four participants were full-time ambulators (WISCI II scores ranged 19–20). The group demonstrated varying degrees of deficits in balance (i.e., mini-BESTest scores ranged 0–25/28).

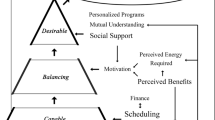

Four themes emerged from the discussion of participants’ photographs: Perceived Challenges, Impact of Perceived Fall Risk, Prevent Falls: Learn through Experience, and Factors Mitigating Impact of Perceived Fall Risk. Each theme included a number of categories (see Table 2).

Theme 1: Perceived challenges

Category 1a. Challenges in the community

In outdoor community environments, situations perceived to increase fall risk included stairs (especially descending), ramps, curbs, and uneven terrain or surfaces, such as grass and “sidewalk[s] with potholes” (Jason) (see Fig. 1a). Uneven pavement “cause[s] wheelchairs to either flip forward or backward…barriers like this exist all over the streets” (Steve). Transitioning between different surfaces was identified as a threat by both ambulators and wheelchair users, as were obstacles in the path such as crowds of people and snow/ice. Susie took a photograph of an outdoor thermometer because “if it’s really cold or really hot it’s going to increase [her] risk of falling” as high and low temperatures affect levels of muscle tone and pain.

In indoor community environments, negotiating public transit was frequently photographed. Subway stations are particularly challenging due to “the rushing of the whole subway system…the intensity of the people and making sure you’re moving fast enough” (Dawn). Other perceived challenges in indoor community environments included heavy doors with no power button, revolving doors, and “any set of stairs like in the mall” (Dawn). Having to walk a long distance to public washrooms was also mentioned as a challenge, as were inaccessible gyms and restaurants (see Fig. 1b).

Category 1b. Challenges in the home

Although less common, challenges were also perceived around and within the home. It was felt that “accessible homes and accessible apartments are almost non-existent” (Steve). Photographs focused on stairs, both within and at the entrances of homes. Narrow or small spaces were discussed, as were obstacles on the floor (see Fig. 1c). “Stepping in and out of the tub, especially when it’s wet” (Dawn) was another challenge highlighted, and participants identified transitions as placing them at risk of a fall (see Fig. 1d). For example, the transition between a carpeted and uncarpeted surface, or the “transition from light to dark…for anybody that’s got a balance issue it’s gonna be a problem” (Robert).

Category 1c. Physical impairments

Poor balance, drop foot, pain, and fatigue were perceived to contribute to an increased risk of falls. Reduced muscular strength was mentioned, for example if “you have no core, you can’t manage your legs” (Steve), as was reduced upper limb movement and function. As Dawn pointed out, if you are on the bus and “don’t have that ability to reach for [the grab handles], then your likelihood to fall is greater.” Not having “100% feeling in [one’s] feet” (Dawn) was also perceived to increase the risk of falls. Some participants expressed a lack of control over their movements. For example, when talking about walking down ramps Jason noted that “if you can’t control the speed if you’re walking then it’s a real problem.”

Category 1d. Variable fall prevention training

Participants had mixed views on whether or not they received adequate fall prevention education and training during rehabilitation. Some of the ambulatory participants discussed learning how to avoid falls from their therapists. Jack said “my physiotherapist told me everything, all the precautions.” Likewise, Dawn said her physical and occupational therapists provided guidance “in terms of things that would help reduce the amount of falls I would have, or safety precautions that I could take to keep myself safe from falling.” While physical and occupational therapists were the professionals most commonly identified as being involved in fall prevention training, a recreational therapist was involved in Dawn’s rehabilitation as well: “…we went onto the [bus] together…seeing how well I could get onto the bus, they taught me how to advocate for a seat on the bus if need be, being able to ring the bell and then [get] off.” In contrast Susie stated that fall prevention “was figured out on our own” and Jason felt that the rehabilitation professionals were “just focused on getting my muscles strong again.” Steve, who used a wheelchair as his primary means of mobility, identified a need for more emphasis on wheelchair skills during rehabilitation: “It’s something that should be of the highest priority as far as I’m concerned.”

Category 1e. Choosing to take risks

Some participants took photos of locations and/or situations in which they had fallen in the past. These photos often reflected challenging tasks that participants believed placed them at a greater risk of falling, like carrying a laundry basket on the stairs and other dual tasks. One participant talked of not implementing his occupational therapist’s recommendation to install a bath seat and then experiencing a fall in the shower. The choice to take a risk may be partly influenced by the length of time since injury, as Robert, who had the most chronic injury, explained “Because I’ve been on my feet for a while now I’m more apt to take more chances and do things as opposed to other people who are just starting out—starting to walk.”

Theme 2: Impact of perceived fall risk

Category 2a. Mobility

With respect to their mobility, participants described the risk of falls as causing them to “slow down…going from one place to the other.” (Jack) When trying to walk from one place to another in the community, and if the environment is perceived as posing a fall risk, “I’ll find an alternative way. Even though it may take a bit more longer.” (Gord) When asked how the risk of falling affects her mobility, Susie discussed the impact on her choice of footwear (see Fig. 2a).

Category 2b. Participation in physical activity

With respect to physical activity, two participants discussed how the risk of falls impacted their ability to exercise at fitness gyms. For example, Jason took a photo of an elliptical as an example of an exercise that he avoids due to the risk of falling (see Fig. 2b). Similarly, Dawn took a picture of a row of bicycles and explained that the risk of falling has caused her to give up a recreational activity that she used to enjoy (see Fig. 2c). Fall risk was also described as having an impact on other physically-demanding activities, such as shoveling snow, raking leaves, and carrying groceries home. Participants described either stopping these activities altogether or changing the way the activity is accomplished.

Category 2c. Emotional well-being

The perceived risk of falls may have impacted the emotional well-being of some participants. A few participants expressed frustration at the inaccessibility of community environments, that “not everyone has equal access to [an] establishment” (Gord). Frustration was expressed about the design of curbs and the hazards created by damaged sidewalks and roads. When Jason was asked why he took a picture of a cramped public washroom he said “I guess frustration because some of these things should not exist.” There was a feeling that inaccessible environments exist because “no one with a disability is consulted and included in the [decision making] process” (Gord). A fear or anxiety about falling was mentioned by several participants, but not all. A few participants who had sustained their SCI through a fall referred to a fear of falling and injuring their spine again. Gord stated “sometimes when I’m looking at black ice and stuff like that I get nervous because…of what happened to me.” Similarly, Jack stated that with “any stairs I always take a precaution and make sure I hold on to the [railing]—because you don’t want to re-injure your spine again.”

Theme 3: Prevent falls: Learn through experience

Participants described strategies that were learned experientially and addressed behavioral and environmental factors. All participants reported that they learned how to avoid falls through the experience of falls or near falls: for example, “my steep learning curve happened every time I fell” (Steve) and “when I first started…it was all trial and error” (Robert).

“…falling out of the chair helps you learn how not to fall out of the chair…kind of like a vicious little circle going on…to realize what are the hazards that you might not necessarily have thought were hazards.” Steve

Category 3a. Slow down

Participants described choosing “to slow down and make sure that you won’t fall…” (Jack) in situations that placed them at a risk of falling. For example, Jack stated “I take all the precautions especially on the ice…I slow down” and when discussing the challenge of public transit, Dawn explained that “if it’s full then I just won’t get on that train and then I’ll just get the next one…”. Gord acknowledged that “we just have to possibly avoid these situations, find alternative routes, be cautious, and just take [our] time; take whatever time [we] need to get from point A to point B.” Avoidance of activities was mentioned by a few participants in particular situations, but overall was not a consistently used strategy.

Category 3b. Increase awareness

Another strategy learned through experience was increasing one’s awareness of the environment (e.g., scanning for hazards in the path ahead), as well as awareness of one’s physical limitations. “Awareness, I think, is one of the key words that I use a lot now.” (Gord) As Susie explained, she “[has] to watch every step.” This increased awareness was viewed by some participants as enabling them to frequent locations they perceived as a fall risk. For example, when Gord shared a picture taken in a park where he had recently fallen, he explained that “I wouldn’t not go to a park or any environment. Just be more aware of certain things, what I can do.”

Category 3c. Modify movement patterns

Participants described modifying their movement patterns, or altering the way they completed a task, to increase stability. For example, Susie stated “I do vacuum sitting down sometimes.” While sharing a picture of the long hallway she walks along in her apartment building, Susie explained that “because there are walls on either side, there’s always something there I can lean against or coast on.” Dawn described a similar situation when descending stairs: “I tend to walk sideways down the stairs…whenever I’m walking down these stairs… I actually put my bum against the wall going down the stairs.”

Category 3d. Use assistive devices

Participants described using external supports to safely complete tasks like stair climbing and bathing. For example, for Jack, who is ambulatory, on “any stairs I always take a precaution and make sure I hold on to the [rail],” whereas Albert, who is a wheelchair user, took a picture of his wheelchair lift since “it is easier than the stairs.” Similarly, Dawn took a photo of the “slip mat in the tub…helps decrease any falls in the bathtub.” Many of the assistive devices were designed for each individual’s home environment. For example, Steve, a wheelchair user, discussed modifications that he made in his home, such as moving kitchen cabinets and counter space “down to [his] level.” Jason provided an example of a support used in the community as he talked about using a strengthening machine at a gym: “I was just thinking about this study and why I could take a picture of it. And I never realized that I used that bar until I actually caught myself—there was a mirror there. And so I saw myself in the mirror. And that’s what caused me to take the picture because otherwise if I didn’t hold onto [the bar] I probably wouldn’t make it to the machine.”

Theme 4: Factors mitigating impact of perceived fall risk

Category 4a. Character traits

When discussing the impact of perceived fall risk, participants described character traits that may alter future behavior in daily activities. Participants described situations where their perseverance and optimism prevented avoidance of activities that may have placed them at greater fall risk. For example, participants described persevering with the task at hand despite a perceived risk of falling or the occurrence of a fall:

“Well there’s risk in almost everything that we do…sometimes you just gotta do what you gotta do.” (Gord)

“If you wipe out totally you stand there, take count, and make sure nothing’s broken and then get back up and keep going.” (Robert)

As well, some participants expressed optimism in their ability to navigate their daily environments and activities: “There aren’t many barriers for me anymore in this chair other than pretty much climbing a ladder. And given enough time I could probably belt myself into this chair and maybe even do that too.” (Steve) Although their perseverance and optimism may have put them at an increased risk of falls, their perceived risk was worth the reward of continued participation in daily activities.

Category 4b. Desire for independence

Participants expressed a desire to be as independent as possible in their day-to-day life. While sharing the picture of the wheelchair lift at his home, Albert stated that the lift represented his desire for “more freedom.” Similarly, Steve explained “I still want to go out with my friends. I still want to have a relationship someday. I still want to do my own shopping. I want to be able to go to restaurants when I’m hungry without having to wait for somebody.”

Discussion

Here we used PEI to explore the factors that contribute to falls and the impact of fall risk as perceived by individuals with iSCI. Participants identified a variety of factors that they felt placed them at risk of falls, highlighting the multifactorial nature of falls. The perceived risk of falls had an impact on the participants’ mobility in their homes and communities, and participation in physical and recreational activity. Yet the impact on their emotional well-being was also evident, as frustration and fear of falling were expressed by some participants. As participants were also asked to take photographs of situations or conditions that lessened their fall risk, participants shared their strategies to mitigate the risk and impact of falls. These strategies were largely learnt through experience with falls or near falls rather than during inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation. The present study contributes uniquely to the topic of falls and fall risk after iSCI by gathering the perspectives and lived experiences of individuals with iSCI. By including individuals’ insights and preferences, this research will contribute to the development of a person-centered approach [27, 28] to fall prevention for individuals with iSCI.

The participants and researchers involved in this study perceived there to be a variety of factors that contribute to falls. The Biological, Behavioral, Social & Economic, and Environmental (BBSE) Model of fall-related risk factors [29, 30] is a framework that can be used to investigate the range of perceived contributors to falls. This model categorizes risk factors into four categories: (1) biological (e.g., balance deficits, muscle weakness), (2) behavioral (e.g., risk taking, fear of falling), (3) social and economic (e.g., inability to pay for assistive devices, lack of support networks), and (4) environmental (e.g., slippery surfaces, poor lighting) [29, 30]. In this study, the perceived challenges that increase fall risk included primarily environmental factors (e.g., challenges in the home and community), and some biological factors (e.g., physical impairments). Fewer behavioral (i.e., choosing to take risks) and social-economic (i.e., variable fall prevention training) factors were highlighted as contributors to falls.

Previous work has also identified environmental and biological factors as perceived causes of falls [1, 7, 9,10,11]. Through semi-structured interviews, Jørgensen, and Roaldsen [10] gained insight into what situations in the environment ambulatory individuals with iSCI felt were hazardous; for example, stairs, uneven ground, and crowds. Obstacles on the ground have also been identified [1, 9]. Reduced strength in the legs and trunk, spasticity and fatigue are biological factors that have been previously identified for ambulatory individuals with iSCI [1, 7, 9, 10]. In wheelchair users, uneven surfaces (environmental), muscle spasms and a loss of balance (biological) were perceived causes of falls [12]. Compared with previous work, our study reports detailed accounts of the perceived contributors to falls. This likely reflects the data collection methods used. Through PEI participants provided a visual display of the lived experience, as well as detailed verbal description of situations perceived as risky for maintaining balance. The present study also highlighted behavior as a contributor to falls. Risk-taking was reported by several participants, which is consistent with previous work examining personality traits and SCI [31]. Individuals living with SCI display greater extraversion (i.e., risk-taking, sensation seeking) than normative samples [32]. The findings presented here suggest that the willingness to take risks may contribute to the high frequency of falls among individuals with iSCI; a finding that disagrees with previous research involving older adults. There is evidence that low extraversion is associated with a greater risk of falls among older adults [33]. The role that personality plays in the risk of falling among the SCI population would be an interesting topic for future research. This finding may also help to guide clinicians to query and address risk-taking behavior in this population.

Identifying strategies to avoid falls was not an objective of this study, but this valuable information came out in PEI. Despite the emphasis on environmental factors when discussing fall risk, participants described strategies that targeted behavior, such as slowing down, increasing awareness of the environment, and using assistive devices. Additional factors mitigating the impact of fall risk, as described by participants, included persevering, being optimistic, and desiring independence. Although participants suggested that these factors helped them to participate in daily activities, it is also possible that perseverance and the strong desire to regain independence led them to risky situations. However, maintaining or achieving independence is an effective fall prevention message according to older adults [34]. In the present study, only one identified strategy was environmental (i.e., modifying home environment). The focus on behavioral strategies in the present study, rather than environmental, likely reflects what participants felt was modifiable. Indeed some participants expressed frustration about the lack of accessibility and maintenance of community environments (see Fig. 1a). As all participants in the present study had experienced at least one fall in the past 6 months, these perspectives on strategies to prevent falls resulted largely from the experience of falling, and hence, the strategies may be more reactive in nature. In future research, it would be valuable to capture the perspectives of the individuals with SCI who have not fallen to explore whether their strategies to avoid falls differ.

With respect to formal fall prevention training, ambulatory participants expressed greater satisfaction with the quantity of training that they received during rehabilitation. In contrast, wheelchair users reported minimal fall prevention training and disappointment with the lack of training in wheelchair skills. The quantity and content of fall prevention training in SCI rehabilitation warrants further exploration.

In our study, PEI allowed participants to engage in problem-solving around their perceived challenges. It is possible that PEI could influence the behavior of individuals living with iSCI and act as an intervention in itself. In this way, PEI may actively engage individuals in informing and guiding the rehabilitation process, and provide a venue for participants to directly share their challenges and lived experiences with their health care team [18]. Further, PEI may enhance the ability of health care professionals to support their clients’ problem-solving and return to activities of daily living. The use of PEI in clinical settings for SCI has not been elucidated and further study may be warranted [18].

The present study included individuals with motor incomplete SCI only; thus, the findings cannot be generalized to individuals with motor complete SCI (i.e., AIS A and B injuries). As falls are also a frequent event for individuals with motor complete SCI (i.e., 64% will fall in a given year [35]), future work should explore the perceptions and experiences of these individuals to enable development of person-centered fall prevention initiatives.

In conclusion, eight individuals with iSCI shared their experiences and perceptions of falls, and the impact on mobility and other physical activity, through photographs. Primarily environmental factors were perceived to place participants at a risk of falls, while a variety of behavioral strategies were adopted to reduce the impact of perceived fall risk on daily life. The data collected in this study may inform future rehabilitation and fall prevention strategies as rehabilitation specialists support individuals living with iSCI as they re-integrate into their everyday lives.

References

Brotherton SS, Krause JS, Nietert PJ. Falls in individuals with incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:37–40.

Amatachaya S, Wannapakhe J, Arrayawichanon P, Siritarathiwat W, Wattanapun P. Functional abilities, incidences of complications and falls of patients with spinal cord injury 6 months after discharge. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:520–4.

Wannapakhe J, Arayawichanon P, Saengsuwan J, Amatachaya S. Changes of functional ability in patients with spinal cord injury with and without falls during 6 months after discharge. Phys Ther. 2014;94:675–81.

Krause JS. Factors associated with risk for subsequent injuries after traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1503–8.

Dryden DM, Saunders LD, Rowe BH, May LA, Yiannakoulias N, Svenson LW, et al. Utilization of health services following spinal cord injury: a 6-year follow-up study. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:513–25.

World Health Organization. WHO Global Report on falls prevention in older age. 2017. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Falls_prevention7March.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2017.

Amatachaya S, Pramodhyakul W, Wattanapan P, Eungpinichpong W. Ability of obstacle crossing is not associated with falls in independent ambulatory patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2015;53:598–603.

Phonthee S, Saengsuwan J, Amatachaya S. Falls in independent ambulatory patients with spinal cord injury: incidence, associated factors and levels of ability. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:365–8.

Phonthee S, Saengsuwan J, Siritaratiwat W, Amatachaya S. Incidence and factors associated with falls in independent ambulatory individuals with spinal cord injury: a 6-month prospective study. Phys Ther. 2013;93:1061–72.

Jørgensen V, Roaldsen KS. Negotiating identity and self-image: perceptions of falls in ambulatory individuals with spinal cord injury—a qualitative study. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:544–54.

Nelson AL, Groer S, Palacios P, Mitchell D, Sabharwal S, Kirby RL, et al. Wheelchair-related falls in veterans with spinal cord injury residing in the community: a prospective cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1166–73.

Nelson A, Ahmed S, Harrow J, Fitzgerald S, Sanchez-Anguiano A, Gavin-Dreschnack D. Fall-related fractures in persons with spinal cord impairment: a descriptive analysis. SCI Nurs. 2003;20:30–37.

Matsuda PN, Verrall AM, Finlayson ML, Molton IR, Jensen MP. Falls among adults again with disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:464–71.

Saunders LL, Krause JS. Injuries and falls in an aging cohort with spinal cord injury: SCI aging study. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2015;21:201–7.

Ohman A. Qualitative methodology for rehabilitation research. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:273–80.

Clark-Ibáῆez M. Framing the social world with photo-elicitation interviews. Am Behav Sci. 2004;47:1507–27.

Harper D. Talking about pictures: a case for photo elicitation. Vis Stud. 2002;17:13–26.

La Vela SL, Balbale S, Hill JN. Experience and utility of using the participatory research method, photovoice, in individuals with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1310/sci17-00006.

Wang CC. Photovoice: a participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. J Women’s Health. 1999;8:185–92.

Wang CC. Youth participation in photovoice as a strategy for community change. J Community Prac. 2006;14:147–61.

World Health Organization. Falls Factsheet. 2012. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs344/en/. Accessed 3 Jul 2016.

Kim MO, Burns AS, Ditunno JF Jr, Marino RJ. The assessment of walking capacity using the walking index for spinal cord injury: self-selected versus maximal levels. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:762–7.

Ditunno JF Jr, Ditunno PL, Scivoletto G, Patrick M, Dijkers M, Barbeau H, et al. The walking index for spinal cord injury (WISCI/WISCI II): nature, metric properties, use and misuse. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:346–55.

Franchignoni F, Horak F, Godi M, Nardone A, Giordano A. Using psychometric techniques to improve the balance evaluation system’s test: the mini-BESTest. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42:323–31.

Jørgensen V, Opheim A, Halvarsson A, Franzén E, Roaldsen KS. Comparison of the Berg balance scale and the mini-BESTest for assessing balance in ambulatory people with spinal cord injury: validation study. Phys Ther. 2017;97:677–87.

Carpenter C, Suto M. Qualitative Research for Occupational and Physical Therapists: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2008. p. 153.

Epstein RM, Street RL Jr.. The values and value or patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:100–3.

Garrino L, Curto N, Decorte R, Felisi N, Matta E, Gregorino S, et al. Towards personalized care for persons with spinal cord injury: a study on patients’ perceptions. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:67–75.

Canadian Patient Safety Institute. Reducing falls and injuries from falls: getting started kit. Available from: www.safehealthcarenow.ca (2013, accessed 24 March 2016).

Canadian Patient Safety Institute. What’s new in falls best practices? 2016. http://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/en/NewsAlerts/News/pages/whats-new-in-falls-best-practices.aspx. Accessed 5 Jul 2016.

Berry JW, Elliott TR, Rivera P. Resilient, undercontrolled and overcontrolled personality prototypes among persons with spinal cord injury. J Pers Assess. 2007;89:292–302.

Rohe DE, Krause JS. The five-factor model of personality: findings in males with spinal cord injury. Assessment. 1999;6:203–14.

LeMonda BC, Mahoney JR, Verghese J, Holtzer R. The association between high neuroticism-low extraversion and dual-task performance during walking while talking in non-demented older adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2015;21:519–30.

Hughes K, van Beurden E, Eakin EG, Barnett LM, Patterson E, Backhouse J, et al. Older persons’ perception of risk of falling: implications for fall-prevention campaigns. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:351–7.

Forslund EB, Jørgensen V, Franzén E, Opheim A, Seiger Å, Ståhle A, et al. High incidence of falls and fall-related injuries in wheelchair users with spinal cord injury: a prospective study of risk indicators. J Rehab Med. 2017;49:144–51.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the participants for their dedication to this project. This work was supported by grants from the Physiotherapy Foundation of Canada and the Neurosciences Division of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association. We thank the reviewers for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Musselman, K.E., Arnold, C., Pujol, C. et al. Falls, mobility, and physical activity after spinal cord injury: an exploratory study using photo-elicitation interviewing. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 4, 39 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0072-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0072-9

This article is cited by

-

The relationship between balance control and thigh muscle strength and muscle activity in persons with incomplete spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2024)

-

Identifying priorities for balance interventions through a participatory co-design approach with end-users

BMC Neurology (2023)

-

The effects of light touch on gait and dynamic balance during normal and tandem walking in individuals with an incomplete spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

Current state of fall prevention and management policies and procedures in Canadian spinal cord injury rehabilitation

BMC Health Services Research (2020)

-

Falls after spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence proportion and contributing factors

Spinal Cord (2019)