Abstract

Introduction

Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma (SSEH) is a rare clinical entity, most often with acute symptomatic spinal cord compression and potentially permanent neurologic deficits. SSEH usually has surgical solutions and a good outcome after hematoma evacuation

Case presentation

A 61-year-old professional weight-lifting coach presented to the emergency department with sudden back pain, rapidly progressive paraparesis, and neurogenic bladder, after an intense training, 5 h previously. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a ventral thoracic epidural hematoma with significant compression at Th3-Th6. Surgical procedure was performed within the first 12 h: decompressive laminectomy from Th3 to Th7 vertebral levels and near total epidural hematoma removal. The patient improved rapidly from Th5 AIS-C to Th7 AIS-D paraplegia with independent ambulation, after the intervention. The rehabilitation program led to further improvement of the neurologic deficits and a favorable outcome, to AIS-E.

Discussion

Weightlifting has been reported as SSEH precipitating factor in young athletes. Our case is unique however, because the athlete was older. The underlying pathophysiological mechanism is represented by intravenous pressure changes and bleeding of the epidural venous plexus during a prolonged Valsalva maneuver, induced by strenuous, repeated efforts. Spondylosis, hypertension, and low doses of aspirin were incriminated as risk factors for SSEH. Prompt diagnosis, emergent decompressive intervention, early rehabilitation, and secondary prophylaxis were essential for a good outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma (SSEH) is a rare neurosurgical emergency, with an incidence of one per million inhabitants [1], accounting for <1% (0.3–0.9%) of the spinal extradural space-occupying lesions [2,3]. SSEH can cause severe morbidity and 5.7% mortality [4].

Due to the extremely rare occurrence of this pathologic entity, literature provides scattered case reports, some small series, and a few associated reviews. Kreppel et al. [5] published a meta-analysis of 613 patients with spinal hematoma. Groen [6] performed a comprehensive literature review in which he analyzed 64 non-operative cases vs. 474 operated, and Fedor et al. [7] added 107 more cases of SSEH (available in English), since Groen’s major review. Raasck et al. [4] identified 65 cases from 12 studies (published between 2000 and 2015), and added 6 new cases.

The typical clinical presentation is characterized by a sequential evolutive paradigm, including a sudden onset with spinal radicular pain, followed by progressive neurological deficits due to spinal cord compression. Most patients present with paraplegia or tetraplegia (in variable degrees of severity), possibly associating neurogenic bladder [2,6,8,9,10]. Misleading symptoms of acute hemiparesis mimicking stroke, have been described in a few cases of cervical epidural hematoma presenting as Brown–Séquard syndrome [8,9,10,11].

Any age groups can be affected, but most cases have been in their 60s or 70s, with a slight predominance of the masculine gender (1.4:1) [2,4,5,6,8]. The SSEH appears to have a bimodal topographic distribution, with highest frequencies in the upper thoracic (Th3–5) and middle to low cervical regions (C4–6) [8,9,10,11,12], distribution strongly dependent on age [8].

Diagnosis is performed mainly with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Management of SSEH usually implies a surgical solution; early decompressive intervention is mandatory with rapid deterioration of the neurological status. Conservative treatment is reserved for subjects with minimal neurological impairment or with high risk for surgery [6,7,11,13,14,15].

Case presentation

Our paper presents the clinical case of a professional athlete, 61-year-old male, with associated comorbidities and risk factors related to SSEH.

He awoke at midnight with severe mid-thoracic pain, and numbness of the lower limbs, that spontaneously developed 5 h after weight lifting.

He was referred to the emergency department with accentuated pain (evaluated 10 on visual analog scale), lower-limb weakness, walking difficulty, and urinary retention.

His past medical history was significant for multiple compensated comorbidities: arterial hypertension (therapeutically balanced with irbesartan and rilmenidine); type 2 diabetes mellitus (managed with diet); and obesity. He chronically received simvastatine and low doses of aspirin (75 mg). He reported occasional episodes of lower back pain, but no history of antecedent trauma.

The patient was afebrile, had stable vital signs, and overall well appearing. He had a muscular constitution (weight = 95 kg, height = 170 cm). Neurological examination revealed Th5 AIS-C paraplegia (strength in both legs was 2/5 and 3/5, with a motor subscore 23/50), hypoesthesia below the Th5 dermatome, decreased bilateral lower-limb reflexes, negative Babinski sign, and decreased rectal tone. Abdominal examination revealed a palpable bladder and urinary retention; Foley catheter drained 700 ml of clear urine.

Preoperative screening tests of hemostasis and coagulation profile were within normal parameters: platelet count 194 × 103/μl, INR 1.2; activated partial thromboplastin time 31 s; and bleeding time 5.2 min.

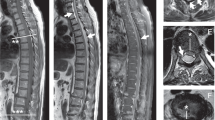

In this acute compressive cord syndrome the diagnosis was based on MRI examination of the spine (Fig. 1), and confirmed by surgery.

Rapidly worsening neurologic symptoms required emergent intervention, performed within the first 12 h. The technical procedure consisted of decompressive laminectomy from Th3 to Th7 vertebral levels, with near total epidural hematoma removal, using surgical microscope. The intraoperative assessment and histopathology analysis confirmed the hematoma, excluding vascular malformations, dural fistula, infection, or tumor.

Postoperative period was uneventful. The drain was removed on postoperative day 2. Evolution was favorable with near-complete regression of the neurological deficits. He improved rapidly from Th5 AIS-C (motor subscore 23/50) to Th7 AIS-D (motor subscore 41/50) and was independent in ambulation on day 7. Urinary dysfunction persisted and the urinary catheter was maintained.

He was subsequently transferred to rehabilitation for bladder training program and physical therapy. Bladder training consisted of electric modulation with interferential currents of medium frequency, tamsulosin (0.4 mg o.d.), and intermittent self-catheterization with pre-lubricated sterile urinary probes. Over the course of the next 14 days, the patient had a steady improvement in his lower extremity function. His outcome was excellent: no motor deficits at discharge, but only mild paresthesia, and subtle micturition problems.

He was reevaluated 3½ months after the surgical decompression of the neural structures (Fig. 2). All neurologic functions had returned: neither motor nor objective sensitive impairments (AIS-E), but only inconstant paresthesia in the lower limbs and insignificant micturition difficulty were found. Urodynamic investigation was recommended.

Discussion

Spontaneous hematoma is most often defined as a condition occurring in the absence of any traumatic event or iatrogenic invasive procedure. Most cases of SSEH have a multifactorial etiology, including congenital and acquired coagulopathies (hemophilia, autoimmune disease, and hemodialysis), platelet dysfunctions, pregnancy, and uncontrolled hypertension. The etiology remains unclear in ~40% [16,17] (up to 50–75%) cases [5].

The differential diagnosis includes a wide variety of medical disorders, such as the following: herniated disc; other hematomas associated with vascular congenital malformations; hemorrhagic tumors; trauma; spinal surgery; or spinal procedures (such as lumbar punctures, epidural anesthesia, myelography, or chiropractic maneuvers).

Messerer et al. [17] proposed a practical classification of the spinal epidural hematomas according to the most probable etiology (whatever the associated factors), in six groups: spontaneous, secondary, iatrogenic, traumatic, recurrent, and idiopathic.

SSEH is generally caused by rupture of the postero-internal vertebral venous plexus [8], secondary to minor barotrauma associated with Valsalva maneuver, described as a trigger factor during different activities: sportive training (weight lifting [18,19,20], breath-hold diving [21], high-level swimming [22], performing sit-ups [3], and stretch exercises [15]) or in apparently healthy individuals, performing highly demanding physical efforts (lifting a heavy box [23] or even piano playing [24]). Abrupt or sustained Valsalva maneuver (playing wind-instruments [25], and a trivial coughing or sneezing [26]) may also trigger a SSEH.

Sportive weight lifting, incriminated as trigger factor for SSEH, was reported by Latzka et al. [18] in a young athlete. Physical effort during lifting heavy objects as precipitating factor related to SSEH was reported in other case studies by Vitali and Steinbok [19], Chen et al. [20], and Kingery et al. [23] in three young healthy subjects, under the 40th. Our subject was at the threshold of old age, had a sportive fit and prolonged his activity as professional coach, performing regularly his training program.

The etiology of SSEH remains controversial. The bleeding is probably of multifactorial origin, incriminating veins and possible arteries. Literature supports both venous and arterial sources of bleeding. The epidural venous plexus is devoid of valves, and is vulnerable to sudden fluctuating hemodynamics and changes in pressure within intra-abdominal and intra-thoracic veins associated with heavy lifting, straining efforts, pregnancy, and uncontrolled hypertension [14]. The anatomical characteristics of the dorsal internal vertebral venous plexus and the segmental distribution of SSEH support the venous origin of bleeding [7,8,21,27,28].

In anteriorly located SSEH, the posterior venous plexus theory would not apply [8]. Beatty and Winston [29] suggested that bleeding can occur also from epidural arteries, because hemorrhage from epidural veins would not create enough pressure to compress the spinal cord.

Vascular structural degenerative changes and spinal venous wall susceptibility to intravenous pressure elevation represent the pathological substrate for the venous disruption. Tearing of the vertebral epidural veins (and possible spinal arterioles) was induced by repeated (minimal) biomechanical conflicts during intense efforts, forced and prolonged Valsalva maneuvers, in a person with degenerative spondylarthrosis [30], and multiple risk factors.

Old age, uncontrolled arterial hypertension, and anticoagulant therapy are main risk factors for SSEH: ~3% of the patients were hypertensive, and 17–30% linked to anticoagulation [16,27,31]. Scattered case studies associated SSEH with anti-platelet drugs (mainly clopidogrel) [32]. Low-dose (100 mg, even 50 mg) aspirin-related SSEH has been reported [28,33,34]; as mentioned afore, our patient received 75 mg of acetylsalicylic acid. Clinicians must consider the remote risk for SSEH in hypertensive patients with antithrombotic treatment.

Ineffectiveness of delayed decompression of the neural structures and removal of the hematoma after 24 h, has been clearly demonstrated [6,7,15,30,35,36]. In our patient the operation was performed within 12 h since the onset of the symptoms, being imposed by the rapidly progressive neurological impairment.

The axiomatic affirmation: “early diagnosis and early surgical intervention can confer a significant prognostic advantage to patients with SSEH” [15] was confirmed by the rapid clinical improvement, without recurrence.

Rehabilitation during the early post-acute phase and monitoring contributed to the favorable functional outcome.

Secondary prophylaxis was essential and our patient received recommendations for life course changing after the hemorrhagic event, to avoid any activity that implies straining while holding his breath. The patient was informed about a possible relapse of the SSEH [17,20] or even occurrence of a spinal cord infarction after weight lifting [37].

References

Holtas S, Heiling M, Lönntoft M. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: findings at MR imaging and clinical correlation. Radiology. 1996;199:409–13.

Figueroa J, DeVine JG. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: literature review. J Spine Surg. 2017;3:58–63.

Chen CL, Lu CH, Chen NF. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma presenting with quadriplegia after sit-ups exercise. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:1170.e3–7.

Raasck K, Habis A, Aoude A, Simões L, Barros F, Reindl R, et al. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma management: a case series and literature review. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2017;3:16043; https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2016.43.

Kreppel D, Antoniadis G, Seeling W. Spinal hematoma: a literature survey with meta-analysis of 613 patients. Neurosurg. Rev 2003;26:1–49.

Groen RJ. Non-operative treatment of spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas: a review of the literature and a comparison with operative cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2004;146:103–10.

Fedor M, Kim E, Ding K, Muizelaar P, Kim K. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: a retrospective study on prognostic factors and review of the literature. Korean J Spine. 2011;8:272–82.

Akimoto T, Yamada T, Shinoda S, Asano Y, Nagata D. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma as a potentially important stroke mimic. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2014;6:15–20.

Mendes PD, Lopes CL, Baptista GS, Scaldaferri PM, Cariri GA. Sudden back pain as clinical presentation of spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2017;75:76.

Perez J, Crespo M, Velez C, Caceres J. Inpatient rehabilitation following operative spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma mimicking stroke: a case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2016;2:16007; https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2016.7.

Matsumoto H, Miki T, Miyaji Y, Minami H, Masuda A, Shogo T, et al. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma with hemiparesis mimicking acute cerebral infarction: two case reports. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;4:262–6.

Raj R, Seppälä M, Siironen J. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: a surgical case series of ten patients. World Neurosurg. 2016;93:55–9.

Kim T, Lee C-H, Seung-Jae Hyun S-J. Clinical outcomes of spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: a comparative study between conservative and surgical treatment. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;52:523–7.

Buchanan CC, Lu DC, Buchanan C, Tran TT. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma and spinal cord infarction following orthotopic liver transplantation: case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4:S359–61.

Abe T, Nagamine Y, Ishimatsu S, Tokuda Y. Spinal epidural hematoma after stretch exercise: a case report. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:902.e1–2.

Dziedzic T, Kunert P, Krych P, Marchel A. Management and neurological outcome of spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:726.

Messerer M, Dubourg J, Diabira S, Robert T, Hamlat A. Spinal epidural hematoma: not always an obvious diagnosis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2012;19:2–8.

Latzka E, Neelwant Sandhu N. Acute radiating low back pain after olympic-lifting. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 2016;26:e98; https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000000359.

Vitali AM, Steinbok P. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma following weight lifting. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35:262–4.

Chen CJ, Fang W, Chen CM, Wan YL. Spontaneous spinal epidural haematomas with repeated remission and relapse. Neuroradiology. 1997;39:737–40.

Tremolizzo L, Patassini M, Malpieri M, Ferrarese C, Appollonio I. A case of spinal epidural haematoma during breath-hold diving. Diving Hyperb Med. 2012;42:98–100.

Fleager Kl, Lee A, Cheng I, Hou L, Ryu S, Boakye M, Massive spontaneous epidural hematoma in a high-level swimmer: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2843–6

Kingery WS, Seibel M, Date ES, Marks MP. The natural resolution of a lumbar spontaneous epidural hematoma and associated radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:67–91.

Chang HJ, Su FJ, Huang YC, Chen SH. Spontaneous spinal epidural hemorrhage from intense piano playing. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:688.e3–5.

David S, Salluzzo RF, Bartfield JM, Dickinson ET. Spontaneous cervicothoracic epidural hematoma following prolonged valsalva secondary to trumpet playing. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:73–5.

Štětkářová I, Jelínková L, Janík V, Peisker T. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma after abrupt sneezing with prompt recovery of severe paraparesis. Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:1555.e3–5.

Tawk C, El Hajj Moussa M, Zgheib R, Nohra G. Spontaneous epidural hematoma of the spine associated with oral anticoagulants: 3 case studies. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;13:8–11.

Finsterer J, Seywald S, Stöllberger C, Krugluger W, Tscherney R, Ulram A, et al. Recovery from acute paraplegia due to spontaneous spinal, epidural hematoma under minimal-dose acetyl-salicylic acid. Neurol Sci. 2008;29:271–3.

Beatty RM, Winston KR. Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma. A consideration of etiology. J Neurosurg 1984;61:143–8.

Arlecchini S, Boriani S. Acute spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1981;7:245–50.

Ozel O, Demircay E, Kircelli A, Cansever T. Atypical presentation of an epidural hematoma in a patient receiving rivaroxaban after total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2016;39:558–60.

Bhat KJ, Kapoor S, Watali YZ, Sharma JR. Spontaneous epidural hematoma of spine associated with clopidogrel: a case study and review of the literature. Asian J Neurosurg 2015;10:54.

Kim KT, Cho DC, Ahn SW, Kang SH. Epidural hematoma related with low-dose aspirin: complete recovery without surgical treatment. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;51:308–11.

Oh JY, Lingaraj K, Rahmat R. Spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma associated with aspirin intake. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:e353–5.

Wang M, Zhou P, Jiang S. Clinical features, management, and prognostic factors of spontaneous epidural spinal hematoma: analysis of 24 cases. World Neurosurg. 2017;102:360–9.

Muñoz Gonzáleza A, Cuelloa JP, Rodríguez Cruza PM, Iglesias Mohedanoa AM, Domínguez Rubio FR, Romero Delgado A, et al. Spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma: a retrospective study of a series of 13 cases. Neurologia. 2015;30:393–400.

Cooper D, Magilner D, Call J. Spinal cord infarction after weight lifting. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:352–5.

Acknowledgements

The SCSANDC’s editorial team, for their constructive observations.

Author contributions

Conception and design: A.A. Provision of study materials and patient: both authors. Literature review and manuscript writing: A.A. Data analysis and interpretation: both authors. Final approval of manuscript: both authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anghelescu, A., Rasina, A. Acute spontaneous thoracic epidural hematoma, triggered by weight-lifting training, in a retired sportsman: case report and literature review. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 3, 17090 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-017-0029-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-017-0029-4