Abstract

Study design

Type II hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial protocol.

Objectives

To (1) evaluate the implementation of coordinated physical activity (PA) coaching delivered by physiotherapists and spinal cord injury (SCI) peers during the transition from in-hospital care to living in a community (implementation objective) and (2) assess the effect of coaching on PA behaviour and psychosocial predictors among people with SCI (effectiveness objective).

Setting

Rehabilitation hospital and home/community settings in British Columbia, Canada.

Methods

Implementation objective: PA coaches (physiotherapists and SCI peers) receive an implementation intervention including training, monitoring, feedback, and champion support. A Theoretical Domains Framework-based questionnaire is collected at baseline, post-training, 2, and 6 months follow-up and semi-structured interviews conducted at 6 months. Effectiveness objective: Using a quasi-experimental design, 55 adults with SCI are allocated to intervention (PA coaching, n = 30) or control (usual care, n = 25) groups. Participants in the intervention group are referred by physiotherapists to receive 11 SCI peer-delivered PA coaching sessions in the community. Control participants received usual care. Questionnaires assessing PA behaviour and psychosocial predictors are administered at baseline, 2-months, 6-months, and 1-year. Semi-structured interviews are conducted to assess intervention satisfaction at 6 months. Analyses include one-way (implementation objective) and two-way (effectiveness objective) repeated measures ANCOVAs for questionnaire-reported outcomes and thematic content analysis for interview data. Data are summarised using the reach effectiveness adoption implementation maintenance (RE-AIM) framework.

Ethics and dissemination

The University of British Columbia Clinical Research Ethics Board approved the protocol (#H19-02694), clinicaltrials.gov registration NCT04493606. Documentation of the adoption process will inform implementation in future sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The scientific spinal cord injury (SCI) exercise guidelines recommend participating in at least 20 min of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity plus muscle-strengthening activity twice per week for fitness benefits, or at least 30 min of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity three times per week for cardiometabolic health benefits [1, 2]. However, individuals with SCI face several multi-level barriers to participating in physical activity (PA), such as pain, transportation, facility and equipment access, inadequate SCI-specific training amongst professionals and staff, and financial barriers [3]. Given these barriers, it is not surprising that individuals living with SCI report the lowest levels of PA, even when compared to other populations with chronic physical conditions [4]. The months after discharge from rehabilitation can be an overwhelming readjustment and are an especially susceptible period for PA levels to drop [5]. Accordingly, it has been suggested that the ideal time to promote an active lifestyle is immediately following discharge [6].

Coordinated support between hospital discharge to the community is needed to help address this critical drop in PA following rehabilitation [6]. Physiotherapists may be well-positioned to promote a physically active lifestyle among clients with SCI in the hospital setting. Evidence supports that physiotherapists perceive themselves to have the training, contact time, and confidence needed to provide information to help their clients with SCI become more physically active [7, 8]. In the community setting, SCI peers are considered one of the most credible sources of PA information for people with SCI [7] and could feasibly continue that PA support following hospital discharge. SCI peers bring the lived experience in communicating PA advice to those who are newly injured and have demonstrated effectiveness for improving PA behaviour previously [9]. Taken together, engaging both physiotherapists and SCI peers through a coordinated referral from the rehabilitation to a community setting is a promising approach to support people with SCI to be physically active.

In British Columbia (BC), Canada, two key opportunities exist to engage hospital physiotherapists and SCI peers as PA coaches (individuals who promote and provide PA advice). GF Strong Rehabilitation Centre is the province’s largest rehabilitation hospital and provides inpatient, outpatient, outreach and clinical support services specific to people with SCI. SCI BC is a charitable, SCI-focused community service organisation that employs SCI peers to deliver their services province-wide. While GF Strong physiotherapists and SCI BC peer staff may discuss PA with their clients as part of usual practice, they have yet to receive formal training in SCI-specific PA coaching, such as that provided by the ProACTIVE SCI intervention, a PA coaching method previously shown to be effective in improving PA behaviour among people with SCI [10, 11]. Furthermore, no standardised referral process exists to transition clients with SCI from hospital to SCI BC’s community services at discharge. Therefore, we will conduct a type II hybrid effectiveness-implementation study to (1) evaluate the effects of implementation strategies on reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of a coordinated PA coaching process among physiotherapists and SCI peers (implementation objective) and (2) assess the effects of physiotherapist referral to community-based, SCI peer-led coaching on PA behaviour and psychosocial predictors among people with SCI (effectiveness objective).

Methods

Design

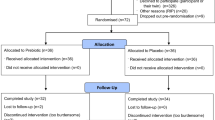

The Standards to Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) checklist was used to guide the reporting of this protocol [12]. We will employ a hybrid Type II effectiveness-implementation study design which is the simultaneous testing of an implementation strategy and a clinical intervention (for a detailed description of this design see [13]). This study design was selected in accordance with recommendations for both the implementation and clinical intervention to have at least indirect evidence (e.g., from a different setting or population) that the interventions are likely to be applicable in the new setting; [13] this has been supported previously [10, 11]. For the implementation objective, a single-group, within-subjects, repeated measures design will be used. For the effectiveness objective, a quasi-experimental design will be used where participants who are interested in receiving PA coaching will be allocated to the intervention group. This study design was selected to increase the reach of the intervention as well as for ethical reasons (given the critical role exercise has in rehabilitation immediately post-injury, it would be unethical to withhold PA prescription and coaching for the purposes of a controlled examination). Please see Fig. 1 for an overview of the study design.

Setting

Rehabilitation hospital setting and community/home setting in Canada.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria and recruitment

As the aim of this project is to implement the intervention using a pragmatic approach, SCI physiotherapists from GF Strong hospital who are interested in delivering the ProACTIVE SCI intervention will be recruited through email. Two SCI BC peer coordinators will be seconded as SCI peer PA coaches (i.e., these individuals are currently employed by SCI BC and a portion of their time will be allocated to PA coaching, paid for by the project).

Participants with SCI will be recruited through physiotherapist referral at GF Strong Hospital. Participants who are not interested in participating in the study at discharge, but enrol in SCI BC’s membership, will be contacted 3 months post-discharge by an SCI BC member to assess their interest in study participation. This is a routine part of the community care process in BC. Reasons for the decline will be documented at this follow-up or PA coaching sessions will be initiated for those who are interested. Physiotherapists will screen clients for eligibility to receive PA coaching. For inclusion and exclusion criteria, see Table 1.

Implementation intervention

Overview

The implementation intervention will consist of two training sessions, provision of the ProACTIVE SCI intervention toolkit, and PA coaching forms which are used to guide and document the PA coaching sessions (see Supplementary Files). Following training, the facilitator (JM) will provide monitoring and feedback of PA coaching and facilitate community of practice meetings (includes addressing issues, refresher training, or training of new physiotherapists). Clinician and SCI peer champions will be identified to act as local resources. Finally, the existing patient discharge summaries will be modified to include a prompt for clinicians to discuss PA prior to discharge. Implementation intervention strategies were informed by a previous pilot training investigation of the ProACTIVE SCI intervention toolkit amongst physiotherapists [10]. Additionally, the Quality Implementation Tool, which outlines specific actionable steps for implementation, was used to inform the adaptation of the implementation strategies and ProACTIVE SCI intervention to the local context [14].

Training

Training day 1 will be delivered in-person by a contributor to the development of the ProACTIVE SCI intervention [10] (https://sciactioncanada.ok.ubc.ca/resources/proactive-sci-toolkit/) and will include an overview of the intervention, demonstration of goal setting and problem solving, behavioural practice, group feedback, and provision of tools. During the four weeks following the first training session, PA coaches will be instructed to practice delivering the ProACTIVE SCI intervention in the clinical or community setting, and document any challenges they experience. The second day of training will be co-delivered by one of the GF Strong champions and JM. The second day of training will include addressing challenges experienced during the practice period, behavioural practice of PA coaching with volunteer clients with SCI, feedback from the facilitators, and a discussion of delivery logistics (e.g., where to access forms, who to contact for referral, coordination of clinical champions with SCI peer champion, etc.). Feedback received from the questionnaires will be analysed following training and implementation intervention components may be adapted to meet the needs of the PA coaches. Training will be delivered at the same time to both SCI peers and physiotherapists to encourage relationship building amongst the two interventionist groups. Additional training will be offered to individual groups to meet setting-specific needs.

PA coaching intervention

Physiotherapists will start the PA coaching conversation in-hospital and tailor the delivered content to what is appropriate for the client’s function and interest as well as the physiotherapist’s time (i.e., not all components of the PA coaching intervention are necessarily delivered at this time). When appropriate (e.g., prior to discharge, if the participant is interested) physiotherapists will refer the client to SCI BC to continue PA coaching in the community.

The PA coaching intervention is based on a previous intervention conducted by our group that was assessed in a randomised controlled trial and demonstrated substantial improvements in PA levels, psychosocial predictors of PA, and fitness for people with SCI more than one year post-injury [11]. The intervention has been described in detail previously [11]. Briefly, PA coaches will conduct an initial assessment to understand the client’s readiness, goals, barriers, preferences, and access to PA resources and mutually select tailored PA-enhancing strategies based on the initial assessment. These strategies include education (SCI exercise guidelines [1], safety, benefits, basics of PA, behaviour change techniques), referral to appropriate peers, programmes, and organisations, and development of adapted exercise prescriptions or action plans. Goals will be based on that target of meeting the international SCI exercise guidelines (strengthening activity twice per week in addition to at least 20 min of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity for fitness benefits or at least 30 min of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity three times per week for cardiometabolic health benefits) [1]. A maximum of 10 follow-up sessions will be delivered over the course of a year, with session timing tailored to the client’s needs. Of note, only physiotherapists will provide exercise prescriptions. If an exercise prescription is needed while in the community setting, SCI peers will refer to a designated kinesiologist to provide an exercise prescription. Physiotherapist-delivered physical activity coaching will be delivered face-to-face while, due to COVID-19 restrictions, SCI peer-delivered sessions will be delivered remotely using telephone or video-conferencing technology.

Primary outcome measure

Implementation objective

RE-AIM: the RE-AIM framework will be used to guide the evaluation of reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance of the implementation intervention. The RE-AIM framework has been used to evaluate behaviour change interventions in PA previously [15, 16]. See Supplementary Table 1 for a description of RE-AIM measures.

Effectiveness objective

Leisure time PA: a modified version of the leisure time PA questionnaire for people with SCI (LTPAQ-SCI) will be used to assess PA behaviour. The LTPAQ-SCI is a self-report measure that assesses minutes of mild, moderate, and vigorous-intensity leisure-time PA (i.e., activity that requires physical exertion and that one chooses to do in their free time [17]) that is broken down into strength training and aerobic activity performed over the past seven days. Support for the LTPAQ-SCI’s criterion validity and test–retest reliability has been previously demonstrated in a sample of 103 men and women with SCI [18]. Recently, construct validity has been supported in a comparison of LTPAQ-SCI scale responses and cardiorespiratory fitness assessed using a graded maximal exercise test among 39 individuals with SCI [19].

Secondary outcome measures

Implementation objective

Implementation factors: the implementation intervention process will be evaluated using a standardised questionnaire measure based on the theoretical domains framework (TDF) [20]. The TDF suggests 14 domains, or behavioural determinants, that evolved from a synthesis of 128 theoretical constructs from 33 theories [21]. PA coaching determinants will be evaluated on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. Support for the internal consistency, reliability, and discriminant validity of the TDF measure has been previously demonstrated amongst physiotherapists [22]. PA coaching behaviours (e.g., educating, referral, prescribing) frequency will be self-reported using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = never and 5 = always.

Semi-structured interviews-PA coaches: semi-structured, individual interviews will be conducted over the phone or video conference. Semi-structured interviews will explore the feasibility and sustainability of implementing PA coaching [23] and factors (barriers and facilitators) that affect PA coaching behaviour using the Theoretical Domains Framework as a guide (Supplementary Files) [21]. Interviews will be recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Modifications to the implementation process: modifications to the implementation process will be documented using the FRAME framework (see Supplementary File) [24].

Feasibility: the percent of people who are recruited and complete the trial as well as percent of counselling sessions completed will be calculated.

Effectiveness objective

Psychosocial predictors of PA: a survey based on the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) model will be used to assess psychosocial predictors of PA (e.g., perceived risks, self-efficacy, planning, and social support) [25]. Measures of the HAPA constructs are drawn from existing measures [3, 26,27,28] and previous SCI studies where possible [9, 11]. All items are assessed on 7-point Likert scales ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”. The ProACTIVE SCI intervention development was informed by the HAPA model (described in detail elsewhere [10]) and has demonstrated improvements across HAPA constructs previously [11].

Semi-structured interviews-clients: semi-structured interviews will be conducted over the phone or by video conference. Semi-structured interviews will explore the impacts of the intervention on physical and mental health, use of healthcare services, quality of life, and function, as well as participants’ satisfaction and future recommendations for the coaching intervention (Supplementary Files).

Sample size

Our implementation objective is powered to detect significant within-subject effects overtime on the TDF measures. Our previous evaluation of the ProACTIVE training amongst physiotherapists, when using within-subject pre-post analyses, demonstrated a very large effect size when averaged across TDF outcomes (d = 1.7) [10]. A minimum of five participants is needed to yield a significant effect of this magnitude in a within-subject, repeated measures ANOVA (4-time points), with β = 0.80, α = 0.05, and a conservative 0.25 correlation among repeated measures. Given this study’s pragmatic focus, the goal is to recruit all available physiotherapists (n = 13).

For the effectiveness objective, based on feasibility estimates calculated using a number of SCI clients admitted yearly to GF Strong (n = 100), an estimated 70% discharged to home, approximately 55% of clients willing to consent to the intervention, and a 20% dropout estimate (based on previous experience in conducting studies in this population) an estimated n = 30 individuals will be recruited to the intervention group and n = 25 will self-select to the control group (see Fig. 1).To ensure our sample size based on feasibility is adequately powered to detect an effect on PA, we conducted a power calculation based on a randomised controlled trial in the in-patient setting with individuals with SCI [29]. Physiotherapists delivered a bi-weekly behavioural coaching intervention to 39 individuals with SCI. A large-sized effect was observed at 6 months (d = 0.89) for self-reported PA. Given our quasi-experimental design, we are powering for a more modest between-groups difference (d = 0.75). Eight participants/condition (N = 16) are needed to yield a significant effect of this magnitude in a repeated-measures ANOVA, with β = 0.80 and α = 0.05. Thus, the feasibility-based projected sample size is adequate to detect a significant effect of the intervention on PA in this context.

Statistical methods

Questionnaire data will be analysed using one- (implementation objective) and two- (effectiveness objective) way repeated measure ANCOVAs, adjusting for potential covariates to be determined prior to analysis. Analyses will be based on intention-to-treat, including all participants with baseline, 2, 6, and 12-month data. Multiple imputations will replace missing data. Sensitivity analyses will be conducted where results including only participants completing at least nine coaching sessions will be compared with intention-to-treat results. For the qualitative data (PA coach semi-structured interviews), we will conduct a deductive content analysis guided by the TDF [21]. For the remaining content in the PA coach and participant interviews, we will use an iterative, inductive content analysis [30]. Member checking will be used to support the generalisability of the findings.

Compliance and retention

An integrated knowledge translation approach, whereby the interventions and supporting materials have been co-developed with participants to meet their needs, should help support continued study participation. Participants will be remunerated for their time at the end of the study to encourage study completion.

Blinding

Data analysis will be conducted blinded; however, due to personnel logistics, the individual collecting the data will be aware of the participant’s group condition when administering the self-report measures.

Adverse events

SCI-specific adverse events related to exercise (e.g., overuse, autonomic dysreflexia) will be recorded. PA coaches will prompt participants to report any adverse events related to study participation and record these on their weekly tracking sheets. A summary of adverse events will be reported using descriptive statistics.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval for the protocol was granted by the Clinical Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (H19-02694). We certify that appropriate consent will be collected and all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers will be followed during the course of this research. Results will be summarised in a journal article, an executive summary which will be shared back to SCI BC and GF Strong Rehabilitation Centre. Additionally, documentation of the adoption process using the FRAME will inform implementation in future sites [24].

Data management, safety, and monitoring

All participant data will be entered on the UBC-hosted version of Qualtrics Survey software and stored on UBC OneDrive. OneDrive is a secure, password-protected storage service. All project computers are password-protected. Only the PI and research coordinator will have access to directly identifiable information, while Co-Is will have access to de-identified data. Two scientists who are part of the trial comprise the data monitoring committee and will monitor trial progress, adherence, and safety. The trial steering committee (including a peer living with SCI, two physiotherapists, a physiotherapist clinical practice lead, the executive director of SCI BC, and two scientists) will monitor daily operations.

Data archiving

The de-identified datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study will be available in the Open Science Framework repository or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Martin Ginis KA, van der Scheer JW, Latimer-Cheung AE, Barrow A, Bourne C, Carruthers P, et al. Evidence-based scientific exercise guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury: an update and a new guideline. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:308–21.

Hoekstra F, Mcbride CB, Borisoff J, Jo M, Spero F, Ma AELJK, et al. Translating the international scientific spinal cord injury exercise guidelines into community and clinical practice guidelines: a Canadian evidence-informed resource. Spinal Cord. 2020;58:647–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0410-1.

Martin Ginis KA, Ma JK, Latimer-Cheung AE, Rimmer JH. A systematic review of review articles addressing factors related to physical activity participation among children and adults with physical disabilities. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10:478–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2016.1198240.

Van Den Berg-Emons RJ, Bussmann JB, Stam HJ. Accelerometry-based activity spectrum in persons with chronic physical conditions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1856–61.

van den Berg-Emons RJ, Bussmann JB, Haisma JA, Sluis TA, van der Woude LH, Bergen MP, et al. A prospective study on physical activity levels after spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation and the year after discharge. Arch Phys Med. Rehabil. 2008;89:2094–101.

Rimmer JH. Getting beyond the plateau: bridging the gap between rehabilitation and community-based exercise. Phys Med. Rehabil. 2012;4:857–61.

Letts L, Martin Ginis KA, Faulkner G, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Gorczynski P. Preferred methods and messengers for delivering physical activity information to people with spinal cord injury: a focus group study. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56:128–37.

Shirley D, van der Ploeg HP, Bauman AE. Physical activity promotion in the physical therapy setting: Perspectives from practitioners and students. Phys Ther. 2010;90:1311–22.

Martin Ginis KA, Tomasone JR, Latimer-Cheung AE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Bassett-Gunter RL, Wolfe DL. Developing physical activity interventions for adults with spinal cord injury. Part 1: a comparison of social cognitions across actors, intenders, and nonintenders. Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58:299–306.

Ma JK, Cheifetz O, Todd KR, Chebaro C, Hoong S, Robert P, et al. Co-development of a physiotherapist-delivered physical activity intervention for adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2020;58:778–86.

Ma JK, West CR, Martin Ginis KA. The effects of a patient and provider co-developed, behavioural physical activity intervention on physical activity, psychosocial predictors, and fitness in individuals with spinal cord injury: A randomized controlled trial. Sport Med. 2019;7:1117–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01118-5.

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter C, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths C, et al. Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI) statement. Br Med. J. 2017;7:e013318.

Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Cheryl S. Effectiveness-implementatation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveneness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med. Care. 2012;20:217–26.

Meyers DC, Katz J, Chien V, Wandersman A, Scaccia JP, Wright A. Practical implementation science: developing and piloting the quality implementation tool. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50:481–96.

Kahwati LC, Lance TX, Jones KR, Kinsinger LS. RE-AIM evaluation of the Veterans Health Administration’s MOVE! weight management program. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:551–60.

Jung ME, Bourne JE, Gainforth HL. Evaluation of a community-based, family focused healthy weights initiative using the RE-AIM framework. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:1–16.

Bouchard C, Shephard RJ. Physical activity, fitness, and health: the model and key concepts. In: Physical activity, fitness, and health: international proceedings and consensus statement. 1994;47:288–303.

Martin Ginis KA, Phang SH, Latimer AE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP. Reliability and validity tests of the leisure time physical activity questionnaire for people with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med. Rehabil. 2012;93:677–82.

Martin Ginis KA, Úbeda-Colomer J, Alrashidi AA, Nightingale TE, Au JS, Currie KD, et al. Construct validation of the leisure time physical activity questionnaire for people with SCI (LTPAQ-SCI). Spinal Cord. 2020;3:311–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00562-9.

Huijg JM, Gebhardt WA, Crone MR, Dusseldorp E, Presseau J. Discriminant content validity of a theoretical domains framework questionnaire for use in implementation research. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1–16.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

Huijg JM, Gebhardt WA, Dusseldorp E, Verheijden MW, van der Zouwe N, Middelkoop BJC, et al. Measuring determinants of implementation behavior: psychometric properties of a questionnaire based on the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1–15.

Wolfenstetter SB. Conceptual framework for standard economic evaluation of physical activity programs in primary prevention. Prev Sci. 2011;12:435–51.

Stirman SW, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019;14:1–10.

Schwarzer R, Lippke S, Luszczynska A. Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA). Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56:161–70.

Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. Bridging the intention–behaviour gap: planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. Psychol Health. 2005;20:143–60.

Sniehotta F, Scholz U, Lippke S, Ziegelmann J, Luszczynska A. Scale for the assessment of phase-specific self-efficacy of physical activity. Heal Psychol. 2002.

Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviours. Prev Med. 1987;16:825–36.

Nooijen CFJ, Stam HJ, Bergen MP, Bongers-Janssen HMH, Valent L, van Lageveld S, et al. A behavioural intervention increases physical activity in people with subacute spinal cord injury: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2016;62:35–41.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res. Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge John Chernesky for his contributions to study conceptualisation.

Funding

This work was supported by a PRAXIS Grant (grant number G2020-21). JKM is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Trainee Award (#17936), the Arthritis Society Post-Doctoral Fellowship (TPF-18-0209), and the Canadian Institute of Health Research Post-Doctoral Fellowship (201910MFE-430114-231890). The funding source did not play a role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JKM—contributed to study conceptualization, writing of the manuscript. KW: contributed to study conceptualization and review of the manuscript. CM: contributed to study conceptualization and review of the manuscript. CM: contributed to study conceptualization and review of the manuscript. CLL: contributed to study conceptualization and review of the manuscript. RC: contributed to study conceptualisation and review of the manuscript. TP: contributed to study conceptualization and review of the manuscript. TT: contributed to study conceptualization and review of the manuscript. HW: contributed to study conceptualization and review of the manuscript. KMG—contributed to the study conceptualization and review of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, J.K., Walden, K., McBride, C.B. et al. Implementation of the spinal cord injury exercise guidelines in the hospital and community settings: Protocol for a type II hybrid trial. Spinal Cord 60, 53–57 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00685-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00685-7