Abstract

Study design

This is a cross-sectional study using questionnaires.

Objectives

This paper investigates the correlation between forgiveness and acceptance of disability and mediation effects of appraisal of disability in people with traumatic spinal cord injury (T-SCI).

Setting

Community-dwelling people with T-SCI in Poland.

Methods

The study assessed forgiveness, appraisal of disability, and acceptance of disability. The association between all the variables was examined by Pearson correlation analysis, and multiple mediation macro Preacher and Hayes’ (Behav Res Methods 40:879–91, 2008)—model 4, including appraisals of disability as a mediator on the relationship between forgiveness and acceptance of disability.

Results

Participants were 163 adults with T-SCI (63 females and 100 males, the average age of the sample was 39.6, SD = 9.38). Forgiveness showed a significant relationship with all dimensions of acceptance of disability. In addition, appraisal of disability, especially determined resolve, overwhelming disbelief, and negative perceptions of disability were mediators between forgiveness and all dimensions of acceptance of disability. In case of acceptance of disability as a subordinating physique relative to other values, full mediation was observed.

Conclusions

Forgiveness along with appraisal of disability is important for explaining disability acceptance. Promoting forgiveness and positive assessments of disability at the same time weakening negative assessments of disability can be favorable for making necessary changes in values, and as a result, for strengthened mental health and successful psychosocial adaptation in individuals with T-SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

From a global perspective, traumatic spinal cord injury (T-SCI) is most often caused by road accidents, plunging into shallow water, falls, and acts of violence [1]. It is a significant basis for disability, which is reflected in various psychosocial consequences, shaped as a result of complex relationships with personal, social, and environmental factors [2]. After the acquisition of T-SCI, people persistently ask the question, “why me?” trying to attribute the cause and responsibility to themselves, others, God, or other higher force [3]. Early theories of adaptation to physical disability included self-blame, blaming others, the extremely negative accompanying emotions (e.g., anger, shame, and resentment), and scapegoating [4]. In the context of the adaptation process, long-lasting self-blame is maladaptive and may indicate concentration on the self in the past, or it may be a past-oriented postimpact coping modality (similarly to blaming others) [5, 6]. Empirical analyses highlight the significant relationship between self-blame and quality of life, post-traumatic stress, psychological distress, and depression (see research overview [7]), confirming theoretical assumptions about its unique importance in the process of adaptation and acceptance of acquired disability [3]. Unforgiveness, directly associated with self-blame (or blaming others) can increase the level of psychological stress and dysfunctional behavior, leading to health problems. Therefore, forgiveness, although challenging for the individual, is desirable for beneficial adaptation and better health in people who have acquired a permanent physical disability [8]. Research indicates that intraindividual changes in forgiveness are positively correlated with adaptive changes [9].

Forgiveness in the literature on rehabilitation and adaptation to disability is presented in the context of the important role of spirituality. It is emphasized that forgiveness can be a powerful tool in achieving successful psychological results and an exceptionally important force in resolving negative emotions and their associated consequences. Forgiveness is treated as a coping strategy and a factor that improves the process of adapting to a disability, leading to improved adaptation effects [10], thus able to promote a good life following acquired physical disability [11]. What is more, living with acquired limitations and changes on almost all levels of functioning, not only forces transformations in existing thinking patterns, but it can also trigger recognition of the need for forgiveness [10, 12]. However, the attitude of forgiving oneself and others, important (despite its limitations) for such a transformation of values to develop further, has not yet been sufficiently explored in people with T-SCI. To date, relatively limited research findings indicate a positive correlation between forgiveness, health, and life satisfaction, even taking into account the effects of socio-demographic variables. At the same time, the type of forgiveness (oneself vs. others) differentiated these connections [8]. Other studies have shown the important role of forgiveness in revealing positive adaptive responses in people with T-SCI [13]. Forgiveness can also help reduce negative reactions to T-SCI which could lead to complications in physical and mental health [8, 10].

From the cognitive perspective, forgiveness constitutes such reformulations of the experienced harm that the harm and its consequences are transformed from negative to neutral or positive. Forgiveness pertains to oneself, another person, or circumstances/situation [14]. The harm, in this case, is the event leading to the acquisition of T-SCI (or the acquisition of T-SCI itself), which radically violated the basic assumptions of the individual about the world and themselves [15]. Forgiveness understood in this way can create a favorable basis for a person to make the necessary transformations in their value system that constitute disability acceptance, according to Wright, for whom acceptance of disability is the perception of limitations in a non-devaluing way as a result of certain transformations in beliefs and appraisal processes [16, 17]. Therefore, forgiveness based on a reevaluation of harm and its consequences may be conducive to adapting the system of values in such a way that the individual will perceive and recognize the preserved opportunities [18].

Referring to Wright’s theory of acceptance of loss, it was assumed that the assessment of disability is an important stimulus for its appraisal and the evaluation of the person’s abilities after the acquisition of T-SCI [17, 18]. Studies confirm that appraisal of disability is a strong factor in psychological adjustment following T-SCI [19, 20]. Since forgiveness includes a disposition to change the perception of harm, appraisal of disability can be a legitimate mediator in the analysis of its relationship with acceptance of disability.

The purpose of this study was, first, to investigate the correlation between forgiveness and acceptance of disability in people with T-SCI, and second, to examine mediation effects of appraisal of disability.

Although in a cross-sectional design it is difficult to prove this relationship directly, the available theoretical and empirical literature provides the basis for hypothesizing that appraisal of disability will mediate the relationship between forgiveness and acceptance of disability in people with T-SCI.

Methods

Participants

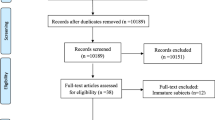

The participants were 191 people with spinal cord injury, of whom 163 adults qualified for final data analysis. Eighteen questionnaires were rejected due to missing data. Inclusion criteria included the following: (1) being 18 years of age or older; (2) having a traumatic injury; (3) tetraplegia or paraplegia. The sample included individuals with both complete and incomplete injuries. A power analysis was conducted and it was found that such a sample size is appropriate for the designed data analysis.

The study was conducted at rehabilitation clinics by trained interviewers (employees or students of psychology were trained in conducting survey studies). The respondents were informed about the purpose of the study. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study. Participation was voluntary (with no remuneration). They were given paper-and-pencil questionnaires, asked to answer all the questions in private, and then to return the completed questionnaires. Participants who expressed willingness were assisted by the interviewer. They completed the Polish versions of the measures as anonymous self-report questionnaires. The research was carried out in 2019.

Materials

Data were collected using the following instruments:

The Polish adaptation of the Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS) [14]. HFS is a multidimensional tool assessing dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations beyond anyone’s control. Participants rate their responses to 18 items on a seven-point Likert-scale from 1 (almost always false of me) to 7 (almost always true of me). Sample items: “With time I am understanding of myself for mistakes I’ve made,” “If others mistreat me, I continue to think badly of them.” The Total HFS score indicates how forgiving a person tends to be [21]. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha value for total HFS was 0.81.

Polish version of The Multidimensional Acceptance of Loss Scale [18]. This is a 41-item instrument that contains four components of disability acceptance: (a) A-I: subordinating physique relative to other values (e.g., “I understand I have limitations, but I can achieve a lot in my daily life”)—Cronbach’s α = 0.89; (b) A-II: enlarging the scope of values (e.g., “It is difficult for me to find other ways of achieving my life goals”)—Cronbach’s α = 0.88; (c) A-III: transforming comparative-status values into asset values (e.g., “I perceive only my limitations”)—Cronbach’s α = 0.86; (d) A-IV: containing the effects of disability (e.g., “My disability is only a small part of who I am”)—Cronbach’s α = (0.79). Satisfactory indicators of reliability and validity of the Polish version of this instrument were obtained [22].

Polish version of Appraisals of Disability Primary and Secondary Scale (ADAPSS; R.E. Dean and P. Kennedy) is a 32-item measure that consists of 6 subscales: fearful despondency (FD), overwhelming disbelief (OD), negative perceptions of disability (NPD), determined resolve (DR), growth and resilience (GR), and personal agency (PA) [23]. Higher scores of subscales FD, OD, NPD indicate more negative appraisals, while lower scores in subscales DR, GR, PA indicate more positive appraisals. The Polish version of ADAPSS showed good validity and reliability [24]. Cronbach’s α for the ADAPSS in the present sample for all subscales is satisfactory (FD: 0.89; OD: 0.87; NPD: 0.88; DR: 0.77; GR: 0.88; PA: 0.79).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted in two stages. First, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were examined to determine whether there were any links between forgiveness, appraisal of disability, and acceptance of disability. Second, the hypothesized mediation models were tested using the PROCESS macro for SPSS written by Preacher and Hayes [25] through bootstrapping of 5000 subsamples. The mediation effects of appraisals of disability on the relationship between forgiveness and acceptance of disability were tested. More specifically, four separate serial mediation analyses were tested with references to subscales of The Multidimensional Acceptance of Loss Scale. When the 95% confidence interval for indirect effect did not include zero, the indirect effect was significant [26]. PROCESS is used to test not only the indirect relationship but also the direct relationships between the constructs. We estimated total effect (TE) (estimates by regressing dependent variables on independent variables), direct effect (DE) (measures the extent to which the dependent variable changes when the independent variable increases by one unit and the mediator variable remains unaltered), and indirect effect (measures the extent to which the dependent variable changes when the independent variable is fixed and the mediator variable changes by the amount it would change if the independent variable increased by one unit). On the other hand R2 estimates % of the explained variance of dependent variables.

Results

The participants were 163 adults (63 females and 100 males) with T-SCI. The average age of the sample was 39.6 (SD = 9.38), with age ranging from 19 to 73 years. Other socio-demographic variables revealed that 37.5% of respondents were married, 12% divorced, 2% separated, 1% widowed, and the remaining 47.5% were single; 64% lived in cities and 36% lived in the country. Average time since injury is 12.05 years (SD = 4.22). Table 1 shows socio-demographic variables.

Table 2 shows correlations between forgiveness, appraisals of disability, and acceptance of disability.

Forgiveness was found to be inversely correlated with all subscales of appraisals of disability, and positively correlated with all subscales of acceptance of disability. All subscales of appraisals of disability were negatively associated with all the subscales of acceptance of disability:

Mediation analyses—appraisals of disability as a mediator of the relationship between forgiveness and acceptance of disability.

Preacher and Hayes’ [25] multiple mediation analyses were used to test the hypothesis that appraisals of disability would mediate the relationship between forgiveness and acceptance of disability. Forgiveness was a predictor, six subscales measuring appraisals of disability (FD, OD, NPD, DR, GR, and PA) were used as mediators, and four subscales of acceptance of disability were the outcome variables.

Taking the relationship between forgiveness and A-I: subordinating physique relative to other values, forgiveness was negatively associated with all ADAPSS subscales: DR, GR, PA, FD, OD, and NPD (see Fig. 1). However, only DR, GR, and PA as mediators were negatively associated with subordinating physique relative to other values. This means that higher scores in this dimension of acceptance of disability associated with a more positive appraisal. The TE of forgiveness (B = 0.53, p = 0.000) on subordinating physique relative to other values was reduced to non-significance (DE: B = 0.14, p = 0.07) indicating full mediation via appraisals of disability. Forgiveness indeed had an indirect effect on subordinating physique relative to other values through growth, resilience (B = 0.06, CI95% = [0.021, 0.110]), and PA (B = 0.06, CI95% = [0.018, 0.107]). The model explained 53% of the variance of subordinating physique relative to other values (F(155, 7) = 24.63; p < 0.001).

Second, the link between forgiveness and A-II: enlarging the scope of values was tested (Fig. 2). NPD and DR were negatively associated with A-II as mediators. The TE of forgiveness (B = 0.61, p = 0.001) on Enlarging the scope of values was not reduced to non-significance with the inclusion of the mediators (DE: B = 0.34, p = 0.001) indicating partial mediation. There was an indirect effect through NPD (B = −0.03, CI95% = [0.000, 0.059]) and DR (B = 0.07, CI95%= [0.040, 0.127]). The mediation model explained 52% of the variance of enlarging the scope of values (F(155, 7) = 23.78; p < 0.001).

Next, the relationship between the tendency to forgive and A-III: transforming comparative-status values into asset values was tested (Fig. 3). OD and DR were negatively associated with A-III as mediators. The TE of forgiveness (B = 0.61, p = 0.001) on transforming comparative-status values into asset values was not reduced to non-significance with the inclusion of the mediators (DE: B = 0.27, p = 0.001) indicating partial mediation. There was an indirect effect through OD (B = 0.06, CI95% = [0.027, 0.120]) and DR (B = 0.09, CI95% = [0.055, 0.136]). The model explained 55% of the variance of transforming comparative-status values into asset values (F(155, 7) = 27.07; p < 0.001).

Finally, the association between forgiveness and A-IV: containing the effects of disability was tested (Fig. 4). OD and DR were negatively associated with A-IV as mediators. The TE of forgiveness (B = 0.50, p = 0.001) on containing the effects of disability was not reduced to non-significance with the inclusion of the mediators (DE: B = 0.36, p = 0.001) indicating partial mediation. There was an indirect effect through OD (B = −0.06, CI95% = [−0.101, −0.027]) and DR (B = 0.03, CI95% = [0.001, 0.059]). The described mediation model explained 36% of the variance of containing the effects of disability (F(155, 7) = 12.67; p < 0.001).

Discussion

The obtained results confirmed the assumed indirect relationship between forgiveness and acceptance of disability in people with T-SCI, already suggested by other researchers in relation to adaptation indicators [6]. The significant and negative correlation between forgiveness and appraisal of disability and positive associations with acceptance of disability were found. Importantly, it was revealed that forgiveness is positively associated with all dimensions of disability acceptance through disability appraisal. The results obtained here provide premises for consistent interpretation and inference. The ability to forgive, i.e., such cognitive transformation of harm and its consequences that they are perceived as neutral or positive may be conducive to recognizing the experienced spinal cord injury and changes in body functions as its features, but not the most important ones for defining oneself as a person [16, 17]. Highly forgiving people are found to appraise their disability more positively, consider it less overwhelming, and have greater acceptance of restrictions, both resulting from their condition related to T-SCI and those experienced in their various social roles [8, 10, 16, 17]. Thus, our results suggest that forgiveness is strongly correlated with better functioning with disability. The underlying mechanism of forgiveness and acceptance of disability understood this way may be similar to the mechanism of attributing the effects of acquired disability and harm, based, e.g., on the internal locus of control [27, 28].

The indirect relationship found in this study between forgiveness and all dimensions of disability acceptance with mediation by appraisal is interesting for at least three reasons. First, except for subordinating physique relative to other values, mediation was only partial. Second, not all categories of disability appraisal served as a mediator. And third, both positive and negative appraisals mediated the relationship analyzed here. These results are consistent with other research findings on the mediation role of positive and negative cognitive assessment in the relationship between forgiveness and psychological health indicators [29]. This means that the role of forgiveness is equally important in attenuating negative assessment and shaping or strengthening positive assessment. Reducing the negative and strengthening positive appraisal of disability leads to more successful coping and adapting [30].

The presented study shows the role of all positive disability appraisal (especially DR) in mediating the relationship between forgiveness and individual dimensions of disability acceptance. With regard to the role of negative disability appraisals in relationships between forgiveness and dimensions of disability acceptance, our findings show that OD and NPD were mediators. Therefore, recognizing the limitations of cross-sectional studies, the obtained results support our hypothesis. The tendency to forgive reinforced by more positive and less negative disability assessments leads to a change in beliefs, values, and life philosophies in such a way that acceptance of the loss of ability is possible. These results are consistent with other findings, e.g., where forgiveness was significant for mental health (e.g., reductions in depression, anxiety, and hostility) [29], favorable for well-being [31], predicted health behavior among people with spinal cord injury [8, 13], and post-traumatic growth [32], as well as with those findings which show that failing to forgive oneself often leads to decreased acceptance of restrictions and negative self-esteem in people with disability [33].

Our study reveals the special role of disability appraisals as a DR in determining the relationship between forgiveness and three dimensions of disability acceptance (enlarging the scope of values, transforming comparative-status values into asset values, and containing the effects of disability). Therefore, the effect of forgiveness in the form of the tendency to appraise restrictions as a challenge that can be successfully resolved proves beneficial for the important transformation of values (their enlarging and changing evaluation criteria) that constitute acceptance of disability. These results confirm the previous study that showed that higher levels of forgiveness were associated with challenge primary appraisals [34]. These findings are also largely consistent with the results of other studies with people with T-SCI, indicating the predictive functions of disability appraisals as a challenge for explaining the acceptance of disability [35].

It is interesting that appraisal of disability as OD is a mediator in the relationship between forgiveness and two dimensions of disability: transforming comparative-status values into asset values and containing the effects of a disability. Higher forgiveness can decrease feelings of helplessness and weaken the rumination about the trauma associated with the onset of permanent disability. Forgiveness as an adaptive and resilient response to trauma can help individuals perceive the maintained possibilities, despite the acquired limitations, achieve greater hope, as well as reduce anger and rumination [36]. Negative relationships found between disability appraisal as OD and acceptance of disability are consistent with the results obtained by other researches who proved the negative importance of this appraisal for successful adaptive effects [30].

The presented research is one of the first to analyze the importance of forgiveness for adaptation, in this case: the acceptance of disability in people with T-SCI. In this respect, it is cognitively valuable. However, it also has some limitations, which is why it should be treated as a preliminary diagnosis and a starting point for subsequent analyses.

First, the study only includes the total score of forgiveness. This was a deliberate decision to analyze the relationship between forgiveness (regardless of its source) and acceptance of disability, being aware that results obtained by Web et al. [8] suggest that the type of forgiveness (self or others) may provide a better understanding of this relationship. Second, the sample of respondents is heterogeneous, not only in terms of the severity of the damage, but also its cause (traffic accident, jump into the water), and time from its acquisition. In future research, these variables should be controlled in analyzes of forgiveness and its links with adaptive effects. Third, all analyzed variables relate to dynamic phenomena and explaining the relationship between them should take into account their processual nature. Thus, longitudinal studies would be more adequate than the applied cross-sectional study. And fourth, a relatively low percentage of explained variance in the level of disability acceptance in its individual dimensions suggests the importance of other mediators. Future studies should explore the mediating role of gratitude and positive emotions in establishing the relationship between forgiveness and acceptance of disability in people with spinal cord injury. It would also be valuable to include socio-cultural factors, including values or religious beliefs in the future analyzes of forgiveness in people with T-SCI.

Despite the indicated limitations, the results of the present study may be useful for therapy and rehabilitation. First, they can increase the awareness of therapists and people with T-SCI about the important role of forgiveness in the process of adapting and transforming the hierarchy of values successfully, necessary for redefining what good life is with limitations resulting from T-SCI. The therapeutic function of forgiveness can be manifested in psychological benefits such as reduction of negative emotions (e.g., anger, depression, guilt, blame, and hopelessness) and becoming emotionally healthier, reframing and finding new purpose in life, increasing self-compassion and self-acceptance. Second, the obtained results reinforce the importance of disability acceptance (understood as the transformation of the hierarchy of values) and negative assessment of disability in the adaptation process of people with traumatic T-SCI, including forgiveness. Therefore, they can be used in rehabilitation interventions focused on the elements of assessment, including injustice perception related to the injustice of damage/disability [37].

Possible therapeutic interventions include those directly focused on training and strengthening forgiveness strategies and, as a result, promoting psychological well-being. Both in the case of external and internal attribution of guilt occurring in people with T-SCI, interventions reorienting the perception of oneself and others as wrongdoers by facilitating sympathy, empathy, and acknowledging the experienced harm are important [37, 38]. Interventions aimed at accepting changes (usually adverse) after the acquisition of T-SCI may also be useful, e.g., strengthening psychological flexibility, helping to find preserved opportunities for development, and using resources and abilities in confronting numerous challenges of everyday life [19, 37]. Importantly, these interventions should take into account the previous personal characteristics or the cultural background of people with T-SCI.

Data availability

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lee BB, Cripps RA, Fitzharnis M, Wing PC. The global map for traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: update 2011, global incidence rate. Spinal Cord. 2011;52:110–6.

Huber JG, Silick J, Skarakis-Doyle E. Personal perception and personal factors: incorporating health-related quality of life into the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;32:1955–65.

Richards JS, Kewman DG, Richardson E, Kennedy P. Spinal cord injury. In: Frank RG, Rosenthal M, Caplan B, editors. Handbook of rehabilitation psychology. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2010. p. 9–28.

Gaventa W. Forgiveness, gratitude, and spirituality. In: Wehmeyer ML, editor. The Oxford handbook of positive psychology and disability. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. p. 226–38.

Livneh H. Quality of life and coping with chronic illness and disability: a temporal perspective. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2016;59:67–83.

Kennedy P, Smithson EF. Spinal cord injury. In: Kennedy P, editor. The Oxford handbook of rehabilitation psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 285–97.

Van Leeuwen CMC, Kraaijeveld S, Lindeman E, Post MWM. Associations between psychological factors and quality of life ratings in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:174–87.

Web JR, Toussaint L, Kalpakjian CZ, Tate DG. Forgiveness and health-related outcomes among people with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:360–6.

Orth U, Berking M, Walker N, Meier LL, Znoj H. Forgiveness and psychological adjustment following interpersonal transgressions: a longitudinal analysis. J Res Pers. 2008;42:365–85.

Web JR. Spiritual factors and adjustment in medical rehabilitation. Understanding forgiveness as a means of coping. In: Dell Orto AE, Power PW, editors. The psychological and social impact of illness and disability. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. p. 455–71.

Dunn DS, Brody C. Defining the good life following acquired physical disability. Rehabil Psychol. 2008;53:413–25.

Stuntzer S, Dalton JA, MacDonald A. Application for forgiveness in rehabilitation psychology: a positive option for change. Int Phys Med Rehab. 2019;4:184–91.

Stuntzer S, Lynch RT, Enright R, Hartley MT, MacDonald A. Forgiveness and psychosocial reactions to disability: a pilot study to examine change in persons with spinal cord injury. Int Phys Med Rehab. 2019;4:171–7.

Thompson LY, Snyder CR, Hoffman L, Michael ST, Rasmussen HN, Billings LS, et al. Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. J Pers. 2005;73:313–59.

Livneh H. Quality of life and coping with chronic illness and disability: a temporal perspective. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2016;59:1–17.

Wright B. Physical disability—a psychosocial approach. New York, USA: Harper & Row; 1983.

Dunn DS. The social psychology of disability. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Ferrin JM, Chan F, Chronister J, Chiu Ch-Y. Psychometric validation of the Multidimensional Acceptance of Loss Scale. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25:166–74.

deRoon-Cassini TA, de St. Aubin E, Valvano AK, Hastings J, Brasel KJ. Meaning-making appraisals relevant to adjustment for veterans with spinal cord injury. Psychol Serv. 2013;10:186–93.

Russel M, Ames H, Dunn C, Beckwith S, Holmes SA. Appraisal of disability and psychological adjustment in veterans with spinal cord injuries. J Spinal Cord Med. 2020;14:1–8.

Kaleta K, Mróz J, Guzewicz M. Polska adaptacja Skali Przebaczenia—Heartland Forgiveness Scale (Polish adaptation of the Forgiveness Scale). Przegląd Psychologiczny (Psychol Rev). 2016;59:401–16.

Byra S. Wielowymiarowa Skala Akceptacji Utraty Sprawności (WSAUS)—polska adaptacja Multidimensional Acceptance of Loss Scale Jamesa M. Ferrina, Fonga Chana, Julie Chronister i Chung-Yi Chiu. (WSAUS—Polish adaptation of the Multidimensional Acceptance of Loss Scale by James M. Ferrin, Fong Chan, Julie Chronister and Chung-Yi Chiu). Człowiek – Niepełnosprawność – Społeczeństwo (Man Disabil Soc). 2017;1:29–50.

Dean RE, Kennedy P. Measuring appraisals following acquired spinal cord injury: a preliminary psychometric analysis of the appraisal of disability. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:222–31.

Byra S. Appraisal of Disability Primary and Secondary Scale—RE. Dean, P. Kennedy—polska adaptacja (Polish adaptation). Przegląd Badań Edukacyjnych (Rev Educ Res). 2017;27a:1–47.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–91.

MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar Behav Res. 2004;39:99–128.

Lichtenfeld S, Maier MA, Buechner VL, Fernández Capo M. The influence of decisional and emotional forgiveness on attributions. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1425.

Waldron B, Benson C, O’Connell A, Byrne P, Dooley B, Burke T. Health locus of control and attributions of cause and blame in adjustment to spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:598–602.

Davis DE, Ho MY, Griffin BJ, Bell C, Hook JN, Van Tongeren DR, et al. Forgiving the self and physical and mental health correlates: a meta-analytic review. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62:329–35.

Kennedy P, Lude P, Elfström ML, Smithson E. Appraisals, coping and adjustment pre and post T-SCI rehabilitation: a 2-year follow-up study. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:112–8.

Akhtar S, Dolan A, Barlow J. Understanding the relationship between state forgiveness and psychological well-being: a qualitative study. J Relig Health. 2017;56:450–63.

Heintzelman A, Murdock NL, Krycak RC, Seay L. Recovery from infidelity: differentiation of self, trauma, forgiveness, and posttraumatic growth among couples in continuing relationships. Couple Fam Psychol. 2014;3:13–29.

Smart J. Disability across the developmental life span: for the rehabilitation counselor. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 2012.

Maltby J, Macaskill A, Gillett R. The cognitive nature of forgiveness: using cognitive strategies of primary appraisal and coping to describe the process of forgiving. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63:555–66.

Groomes DAG, Leahy MJ. The relationships among the stress appraisal process, coping disposition, and level of acceptance of disability. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2002;46:15–24.

Wade GN, Tucker J, Cornish MA. Forgiveness interventions and the promotion of resilience following interpersonal stress and trauma. In: Kent M, Davis MC, Reich JW, editors. The resilience handbook: approaches to stress and trauma. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2014. p. 256–69.

Monden KR, Trost Z, Scott W, Bogart KR, Driver S. The unfairness of it all: exploring the role of injustice appraisals in rehabilitation outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61:44–53.

Wade NG, Worthington EL Jr. In search of a common core: a content analysis of interventions to promote forgiveness. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 2005;42:160–77.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB was responsible for study concepts, reviewing of literature and writing of introduction, description of measures, writing summary of findings and discussion and also research limitations, and updating reference list. JM was responsible for study concepts, collection of research material and statistical analysis, description of measures, interpretation of results. KK was responsible for study concepts, research and statistical analysis, interpretation of results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Byra, S., Mróz, J. & Kaleta, K. Forgiveness and acceptance of disability in people with traumatic spinal cord injury—the mediating role of disability appraisal. A cross-sectional study. Spinal Cord 58, 1317–1324 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0507-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0507-6