Abstract

Study design

Qualitative survey.

Objectives

Examine clinicians’ perspectives on adherence to published evidence-based guidelines and clinician-perceived barriers, and facilitators to optimising inpatient bladder management within one Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) service.

Setting

Surgical Hospital (acute care) and SCI Unit (sub-acute, rehabilitation) in Western Australia (WA).

Methods

Clinicians reviewed an ‘Evidence Matrix’ summarising published clinical practice guidelines and recommendations for SCI bladder management. Focus groups examined the extent to which current practice adhered to recommendations and identified perceived barriers and facilitators to optimal management. Data were analysed thematically using a deductive approach.

Results

Current management closely mirrors published recommendations. Key facilitators included long-standing prioritisation of rapid progression from urethral indwelling (IDC) to a 6 hourly intermittent catheterisation (IC) protocol; regular competency audits of catheterisation technique; and a Spinal Urology Clinical Nurse Consultant (CNC) position. Barriers included limited resources/staffing; restricted access to Neuro-urology consultation; inter-disciplinary communication gaps; and delays in determining and implementing long-term bladder management.

Conclusions

Inpatient SCI bladder care in WA closely emulates published evidence, although adherence at other sites may reveal different practices. Bladder management was found to have been facilitated by a strong culture of practice led by Neuro-urologists, informed by evidence and embraced by Senior Clinicians. Further reduction in duration of initial IDC, provision of early and ongoing Neuro-urology consultations as part of standard care, increased interdisciplinary communication and dedicated SCI Urology theatre lists would further optimise management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After spinal cord injury (SCI), changes in bladder function are associated with altered urinary voiding dynamics, bladder hypoperfusion, damage to the urothelial barrier and dysregulated inflammatory responses render patients susceptible to urinary tract infection (UTI) and other urological complications [1].

Initial management is directed at preventing bladder over-distension, usually by indwelling catheterisation (IDC), to allow continuous drainage until post-injury diuresis resolves, often at 7–10 days [2]. Subsequent management varies according to clinical presentation, hospital policy and patient preference. During in-patient stay, although IDC may still be required for some patients, research evidence shows that intermittent catheterisation (IC) may reduce UTI risk [3,4,5,6]. Indeed, our recent cohort study demonstrated associations between longer duration of IDC, earlier occurrence of UTIs and higher UTI rates [7]. While IDC is associated with a high urological complication rate [8] and IC is generally preferred [9, 10], early IC is not always practiced [11]. A recent study on SCI bladder management in Australia and New Zealand reported variation in catheterisation methods between centres and highlighted gaps between evidence and practice [12]. Perceived challenges to implementing best practice included social, economic, and resource factors.

As a follow-up to that study [12], we therefore conducted an investigation to 1) examine the extent to which recommendations in published SCI bladder-related clinical practice guidelines are followed and 2) determine Clinician-perceived barriers and/or facilitators to optimising bladder management, during acute care and sub-acute rehabilitation at one centre following new traumatic SCI.

A number of quantitative studies have investigated outpatient (chronic) neurogenic bladder management by engaging with consultant urologists, for example using a national data base [13] and written surveys [14,15,16,17]. Our investigation is qualitative in nature and extends these findings by examining in detail the approaches of complete medical and nursing teams in the delivery of bladder care during the entire in-patient journey.

Methods

This paper is reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research [18].

Approach

A qualitative approach incorporating focus groups was taken, since this is amenable to in-depth discussion that can provide practical answers to questions relevant to clinicians and policy makers.

Participant recruitment

Purposive sampling was undertaken to explore a range of views held by Clinicians involved in post-SCI inpatient care in Western Australia (WA). Senior staff at the two hospitals managing SCI in the state distributed written invitations and study information to senior and non-senior medical and nursing staff in relevant positions. Eleven focus groups were held, attended by 44 consenting staff at the ‘Surgical Hospital’ (Royal Perth Hospital): 1 Spinal Registrar, 6 Senior Nurses: 5 in Orthopaedics, 1 in Intensive Care; and at the ‘SCI Unit’ (Fiona Stanley Hospital): 2 Spinal Rehabilitation Consultants, 3 Neuro-urologists, 10 Senior Nurses, 16 Registered/Enroled Nurses. The sample of 44 participants represented ~70% of relevant nursing and medical staff.

Procedure

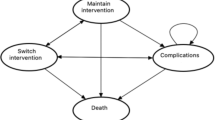

Focus groups were semi-structured, allowing exploration of emerging themes and salient issues in relation to optimal bladder-related clinical practice [19]. Prior to focus groups an ‘Evidence Matrix’ [20] (Supplementary File 1) summarising findings from a recently published systematic review of SCI bladder management guidelines [21] was distributed to medical and nursing staff in relevant positions at the Surgical Hospital and SCI Unit. Care was taken to group participants in a way to minimise reservations in responding associated with seniority hierarchies. Each focus group, of ~1 h duration, was led by an independent facilitator with a nursing background, audio recorded and attended by female authors with more than 50 years research and 40 years clinical experience collectively (Clinical Researchers: LG, background in Neuro-physiotherapy, and GK, SCI background in Nursing; and Professor of Research: SD, background in basic and clinical neurotrauma research). The authors, who were acquainted with some of the Participants in each focus group, introduced themselves and outlined the study objectives, procedures and intended methods for data analysis. Participants were assured that anonymity would be protected and the Chatham House Rule was observed [22], so that participants were aware they could speak freely about their personal views, without comments being attributed to specific individuals or interpreted as being representative of an institution/employer. The facilitator asked semi-structured questions, using an interview guide developed by the research team and pre-tested at the SCI Unit (see Fig. 1). Questions were based on elucidating the extent to which practice aligned with evidence, exploring Clinicians’ reflections on barriers and facilitators of practice and on how management might be optimised. After 11 focus groups involving 44 participants, ‘saturation’ was reached, with no new themes arising.

Data analysis

Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim, with data de-identified, coded and analysed thematically by a deductive approach [23], using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (NVivo11, QSR International) [24]. Thematic analysis focused on current practice in relation to the Evidence Matrix [20] (Supplementary File 1), barriers and facilitators to practice and potential change strategies. Transcripts were coded according to these themes and emerging relevant topics. Initially, two randomly selected transcripts were independently coded by two authors (LG & GK), who were previously aware of the main policies for inpatient SCI bladder management in WA, but not the extent to which these were adhered to in practice. These authors then met to resolve discrepancies and refine the coding framework (Table 1) before analysing all transcripts. To maximise trustworthiness, two Investigators (LG & GK) met several times to discuss and refine categorisation, minimising interpretation error by continually referring back to transcripts and checking accuracy.

Results

Current bladder management practice

In WA, acutely injured patients with SCI are admitted to the Surgical Hospital where initial bladder management is by IDC. Once medically and orthopaedically stable, patients are transferred to the SCI Unit for rehabilitation, including urodynamic bladder assessment and specialist bladder management. At the SCI Unit, if there are no contraindications, such as sepsis, urethral trauma or a requirement for surgery, the IDC is generally removed. Unless/until satisfactory spontaneous voiding returns, that is with minimal associated post-void residual volumes on ultrasound scanning and acceptable detrusor pressures according to Urology review of urodynamic assessment, patients are managed by nursing staff-administered IC (‘staff-IC’). The staff-IC regimen involves complete bladder emptying at least 6 h to reduce infection risk due to stasis, in combination with controlling fluid intake to prevent bladder volumes over 500 mL and upper urinary tract damage. Staff-IC is usually continued until long-term management is implemented; preferably by clean intermittent self-catheterisation (CISC), otherwise via suprapubic catheterisation (SPC), which may be suitable when hand function is very limited, promoting functional independence; or, much less frequently due to known association with increased risk of UTI, via IDC.

Extent to which best practice management is followed

Clinicians reported that in-hospital bladder management closely mirrors the Evidence Matrix, with close adherence to recommendations across all three categories: catheterisation, assessment and patient education/training.

Practice differed partly from one recommendation with ‘B’ grade evidence: patient education and training in CISC is extensive, but not ‘standardised’, and the quality and quantity of teaching and follow-up is inconsistent, depending on staffing levels and experience. The only other differences were in relation to recommendations with ‘0’ grade evidence: catheters are not always changed prior to urine collection for pathology testing; sterile technique is not considered for individuals conducting CISC experiencing recurrent UTIs; and standard polyvinyl rather than pre-lubricated/hydrophilic catheters are used for IC.

Barriers and facilitators to optimal management

In relation to all Evidence Matrix recommendations, and to additional aspects of bladder care, the following major themes concerning key areas of service delivery with potential to impact urological health outcomes were identified (Table 2 lists all barriers and facilitators, and additional representative quotes):

Surgical hospital

Clinicians described consistent acute management according to hospital protocol and Nursing Practice Standards.

Theme 1.1: Catheterisation is limited to IDC

Urethral IDC is used predominantly, unless contraindicated, such as in the rare event of concomitant pelvic trauma/urethral injury, when SPC may be implemented. For patients with severe cervical injury, while SPC may be appropriate long-term management, this option is usually only considered during rehabilitation at the SCI Unit.

Staff-IC is not conducted at the Surgical Hospital despite recommendations indicating, and SCI Unit Neuro-urologists in agreement, that it is safe and beneficial after resolution of diuresis and once the patient is medically stable. Clinicians described several perceived barriers to staff-IC (see Table 2), however, Senior Nurses expressed a willingness to conduct staff-ICs if this policy were to be adopted and adequate education provided.

Theme 1.2: Acute care and rehabilitation are delivered by different hospitals

Care being delivered by two different hospital services was perceived by Senior Clinicians at both sites as a barrier limiting communications and continuum of care. Only during rehabilitation at the SCI Unit is Neuro-urological consultation and specialist SCI bladder nursing provided. There was agreement across sites that, in early acute SCI, the priority is ensuring the survival of highly traumatised, often critically unwell, patients while “urological concerns are understandably put to one side”. However, as one SCI Unit Doctor noted, once patients are medically stable, the absence of a mechanism for Neuro-urological referral at the Surgical Hospital is a barrier to optimal management for patients with longer acute admissions. Earlier assessment would enable consideration of clinically indicated treatments, such as pharmaceutical support to prevent/reduce development of detrusor overactivity and reflux.

SCI unit

Clinicians described the complexity of bladder management during rehabilitation, highlighting a number of facilitators and barriers to optimal practice.

Theme 2.1: Health service changes have impacted delivery of care

Until 2014, a dedicated Neuro-urological team at the SCI Unit prioritised weekly consultation for every patient via ward rounds and a high degree of staff development in bladder rehabilitation. Senior Nurses attributed the high standard of current management to this culture of practice, which evolved at the SCI Unit over several decades. The policy of early removal of IDCs to instigate staff-IC stems from a ‘long-standing mantra’ of WA Neuro-urologists and a subsequent ‘collective mindset’ at the SCI Unit that prevention of urinary complications is essential and 6 h IC should be implemented consistently, without compromise. Senior Nurses with extensive experience and expertise continue to manage staff-IC protocols, but following health service changes in 2016, there is no longer a Neuro-urology Consultant and Registrar dedicated to the Unit; patients are seen only upon referral, rather than per standard practice. Senior Clinicians expressed concern that this change has compromised bladder care and a powerful mechanism for early identification of bladder-related issues has been lost. While two of three participating Neuro-urologists expressed satisfaction with the current system, many Clinicians described the transition between service models as difficult, with impacts on patient care not well appreciated by hospital policy/decision makers.

Theme 2.2: Maintaining a high-standard staff-IC protocol is increasingly challenging

According to Senior Nurses, factors associated with (nursing) staff experience and education continue to facilitate effective administration of early staff-IC; however, Nurses described growing barriers in relation to staffing and gaps in staff education (details provided in Table 2).

Theme 2.3: Determining appropriate long-term bladder management is complex

During rehabilitation, the advantages/disadvantages of various bladder drainage methods are discussed with patients in the context of their individual preferences and goals. One Doctor stated that ‘best practice’ determines appropriate long-term management, which is recommended to the patient, who considers the advice and ultimately makes the final decision. However, determining what is best for the patient is not straight forward and barriers to this process are listed in Table 2.

Patients with potential to master CISC are encouraged to commence one-to-one training as early as possible with experienced, confident Nursing Staff. Clinicians described a number of facilitators to this process, involving multi-disciplinary collaboration (see Table 2).

However, Clinician responses again indicated that SCI inpatient demographics are changing, with an increasing proportion of older patients with pre-existing mobility issues and comorbidities, which are barriers to performing CISC (these and other barriers are listed in Table 2). In relation to this, Nurses described the “insistence by Urologists” for certain patients to continue trying (with great difficulty) to self-catheterise as detrimental. Some Nurses called for earlier implementation of SPC for select patients with poor mobility/dexterity to facilitate in-hospital coping, rehabilitation and long-term lifestyle, expressing concern that their perspectives (and those of patients) were not being adequately considered. Neuro-urologists acknowledged that self-catheterisation was enormously challenging for some patients, but described a determination to address each obstacle, rather than viewing obstacles as reasons to “give up” and opt for permanent IDC.

Theme 2.4: Delayed implementation of suprapubic catheterisation

This was a major topic concerning Senior Clinicians. Responses across disciplines consistently agreed that for patients with severe, high-level SCI, SPC should commence early during rehabilitation, however barriers to best practice associated included scheduling delays (detailed in Table 2) and according to Senior Nurses, Neuro-urologists being reluctant to implement SPC until just prior to hospital discharge“…puts pressures on theatres” and “…sets them up for failure”.

Long theatre waitlists were also consistently identified across focus groups as a major barrier. Senior Nurses recounted that in previous years, patients with SCI were referred to a dedicated SCI-Urology theatre list, whereas procedures are now scheduled by the hospital’s general Urology department, prioritising life-saving surgeries. Subsequent delays frequently require patients to be sent home with IDC and readmitted weeks/months later for SPC insertion—a practice described by Senior Clinicians as “unacceptable”. Neuro-urologists described a preparedness to recommend early SPC for those with high cervical injuries, although agreed that implementation delays had been an obstacle to this.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the extent to which in-hospital SCI bladder management aligns with evidence and describing Clinician-perceived barriers and facilitators to optimal practice.

Early bladder care and timing of IDC removal

IDC is an appropriate method for the 7–10 day post-SCI diuresis period, allowing continuous bladder drainage and hourly urine output monitoring as part of major trauma medical care. Thereafter, while alternative management may reduce UTI risk [3, 4], it is not uncommon for IDC to continue. In WA, the median duration of initial IDC is 21.5 days, but higher (40.4 days) for patients with complete tetraplegia, reflecting Surgical Hospital length of stay [7]. A study conducted at another Australian service reported median IDC duration of 58 days [6].

Such prolonged IDC is likely to increase UTI risk. A prospective study of inpatients with new SCI showed that IDC duration of more than 30 days increased the risk of UTI fourfold compared with other bladder drainage methods [25].

SCI bladder rehabilitation is a complex specialty

The historical context and medical stewardship in the evolution of rehabilitation protocols are important. Senior Clinicians described a culture of high-standard evidence-based practice dating back to strong leadership during the 1950s and research that led to establishing early staff-IC, with improved urological outcomes [26]. A ‘Neuro-Urology and Urodynamics Unit’ was established at the SCI Unit in 2002, providing specialist consultation to all patients and world-class staff training.

Challenges in maintaining and further optimising care

Budgetary pressures and system changes can be challenging for any SCI service. At this centre, a new health model and relocation of the SCI Unit in 2014 presented specific challenges to maintaining established standards. A down-sized Neuro-urology team and cessation of weekly specialist reviews were perceived barriers, resulting in fewer interdisciplinary discussions about patient progress. This may explain the disconnect between perspectives on realistic long-term management for certain patients. Neuro-urologists, consulting infrequently, are focused on patients’ potential to achieve optimal outcomes, whereas Nursing Staff observe day-to-day progress, motivation levels and the struggle associated with achieving goals. Clinicians indicated that without regular discussions, differences of opinion were not resolved and it was inevitable for patients to receive mixed messages about appropriate management. The timing of SPC implementation, for example, is not a simple decision and has no evidence-based guideline associated with it. At some centres, patients with high level, neurologically complete SCI, commence SPC acutely [11, 27]. While some Nurses in the current study favoured this option, Senior Clinicians preferred SPC to be considered only during the sub-acute phase when the patient’s prognosis is clearer. It would seem appropriate to at least avoid extensive delays once the decision to adopt SPC is made, as this will in turn reduce long-duration IDC, which increases the risk of UTIs and other complications [28, 29].

Not all challenges are unique to WA. One study of brain injury also found organisational culture and inter-disciplinary communication were important domains [30]. Another identified long waiting lists and limited resources affecting delivery of SCI-related interventions as practice barriers, describing the development of a clinical care pathway to overcome region-specific obstacles [31].

Implications for practice and clinician suggestions

To minimise IDC durations, it may be beneficial to establish a staff-IC protocol for select patients once medically stable, who are at higher risk for UTI. In WA this would require support from Senior Clinicians at the Surgical Hospital, clear policy regarding patient selection, IC training and ongoing competency auditing and a mechanism for Neuro-urological consultation. Quality improvement activities at the SCI Unit may also be considered, since our recent cohort study [7] described several instances of IDC being prolonged for >3 weeks after patients were transferred to the Unit.

Establishing Case Coordinator/Liaison positions may improve continuum of care and provide greater patient support following SCI, particularly when acute care and rehabilitation are provided by different Clinicians and/or at separate sites. Adopting a clinical care pathway for SCI bladder management might also be beneficial, emphasising facilitators identified by this study and others, such as the international ‘Ability Network’ in relation to spasticity management [31], which also found an individualised approach and interdisciplinary coordination of care to be positive factors.

Interdisciplinary discussions, which will potentially enhance and expedite clinical decision-making, would be fostered by adopting regular patient progress meetings. At the SCI Unit, this might involve reinstating weekly Neuro-urology rounds. One Senior Clinician suggested greater Neuro-urology input is required, ideally from a dedicated Consultant and Registrar. Expanding the Spinal Urology CNC position, which was repeatedly identified as a key facilitator of best practice, was recommended, as was formalised education on SCI-specific bladder dysfunction and management for medical Residents rotating through the Spinal Unit.

Finally, centres managing SCI should make available a range of catheter types to enable patients with different abilities and circumstances to conduct CISC properly and safely. Catheter type for IC may also impact on UTI risk. Although high-quality published evidence on this topic has been conflicting [32,33,34,35], a systematic review in 2017 found hydrophilic-coated catheters decreased the risk of UTI and urethral trauma, as well as improving patient satisfaction [36]. Senior Nurses in WA favoured the use of pre-lubricated catheters for staff- and CISC, believing this also obviates poor CISC practices, such as applying lubricant directly with the hands. Indeed, pre-lubricated catheters have been introduced at the SCI Unit since the conclusion of this study.

Study limitations

Rather than audit data, this study involved self-reporting, with some recall bias likely. Some findings were supported, however, by data from our recent cohort study [7], conducted in parallel. While purposive sampling ensured a wide representation of views, including those of experienced SCI Clinicians, further studies are needed to examine practice at other sites, where other barriers/facilitators might be revealed.

Conclusions

In-hospital SCI bladder management in WA closely emulates published clinical guidelines. This study demonstrates that despite the evolution of a robust culture of practice, underpinned by Clinicians embracing evidence-based recommendations, systems-related barriers can arise, eroding quality of care. Study findings could inform national guidelines for optimising SCI bladder management.

Data availability

Data are stored on a password protected USB and on NVivo. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study will be made available in The University of Western Australia’s research repository; https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/datasets.

References

Vigil HR, Hickling DR. Urinary tract infection in the neurogenic bladder. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5:72–87.

Middleton J, Ramakrishnan K, Cameron I. Innovation NAfC. Management of the Neurogenic Bladder for Adults with Spinal Cord Injuries. 3rd Edition. Agency for Clinical Innovation, Chatswood NSW, 2014. p. 1–15.

Everaert K, Lumen N, Kerckhaert W, Willaert P, van Driel M. Urinary tract infections in spinal cord injury: prevention and treatment guidelines. Acta Clin Belgica. 2009;64:335–40.

Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, et al. Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection in Adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:625–63.

Ryu KH, Kim YB, Yang SO, Lee JK, Jung TY. Results of urine culture and antimicrobial sensitivity tests according to the voiding method over 10 years in patients with spinal cord injury. Korean J Urol. 2011;52:345–9.

Hennessey DB, Kinnear N, MacLellan L, Byrne CE, Gani J, Nunn AK. The effect of appropriate bladder management on urinary tract infection rate in patients with a new spinal cord injury: a prospective observational study. World J Urol. 2019;37:2183–8.

Goodes LM, King GK, Rea A, Murray K, Boan P, Watts A, et al. Early urinary tract infection after spinal cord injury: a retrospective inpatient cohort study. Spinal Cord 2019;58:25–34.

Nicolle LE. Urinary catheter-associated infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26:13–27.

Guttmann L, Frankel H. The value of intermittent catheterisation in the early management of traumatic paraplegia and tetraplegia. Paraplegia 1966;4:63–84.

Hill TC, Baverstock R, Carlson KV, Estey EP, Gray GJ, Hill DC, et al. Best practices for the treatment and prevention of urinary tract infection in the spinal cord injured population. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:122–30.

Zermann D, Wunderlich H, Derry F, Schroder S, Schubert J. Audit of early bladder management complications after spinal cord injury in first-treating hospitals. Eur Urol. 2000;37:156–60.

Goodwin DM, Brock J, Dunlop S, Goodes L, Middleton J, Nunn A, et al. Optimal bladder management following spinal cord injury: evidence, practice and a cooperative approach driving future directions in Australia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:2118–21.

Cameron AP, Wallner LP, Tate DG, Sarma AV, Rodriguez GM, Clemens JQ. Bladder management after spinal cord injury in the United States 1972 to 2005. J Urol. 2010;184:213–7.

Razdan S, Leboeuf L, Meinbach DS, Weinstein D, Gousse AE. Current practice patterns in the urologic surveillance and management of patients with spinal cord injury. Urology 2003;61:893–6.

Rikken B, Blok BF. Management of neurogenic bladder patients in The Netherlands: do urologists follow guidelines? Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27:758–62.

Bycroft J, Hamid R, Bywater H, Patki P, Craggs M, Shah J. Variation in urological practice amongst spinal injuries units in the UK and Eire. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:252–6.

Kitahara S, Iwatsubo E, Yasuda K, Ushiyama T, Nakai H, Suzuki T, et al. Practice patterns of Japanese physicians in urologic surveillance and management of spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord 2005;44:362–8.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57.

Patton MQ. Qualitative Research. In: Howell BSEDC, editor. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2005. p. 1633-6.

Wright B, Bragge P. Spinal Cord Injury Bladder Care Recommendations Matrix. VIC, Australia: BehaviousWorks Australia, Monash University; 2015.

Bragge P, Guy S, Boulet M, Ghafoori E, Goodwin D, Wright B. A systematic review of the content and quality of clinical practice guidelines for management of the neurogenic bladder following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2019;57:540–9.

Royal Institute of International Affairs. Chatham House Rule. Chatham House website [updated 2002]. https://www.chathamhouse.org/about/chatham-house-rule.

Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. CA: Sage Publishing, Thousand Oaks; 1998.

Edhlund B, McDougall A. Nvivo 11 Essentials. First Edition. Stallarholmen, Sweden: Lulu. com; 2016.

Escalarin De Ruz A, Garcia Leoni E, Herruzo Cabrera R. Epidemiology and risk factors for urinary tract infection in patients with spinal cord injury. J Urol. 2000;164:1285–9.

Pearman JW. Urological follow-up of 99 spinal injured patients initially managed by intermittent catherisation. Br J Urol. 1976;48:297–310.

Noll F, Russe O, Kling E, Botel U, Schreiter F. Intermittent catheterisation versus percutaneous suprapubic cystostomy in the early management of traumatic spinal cord lesions. Paraplegia 1988;26:4–9.

Stohrer M, Blok B, Castro-Diaz D, Chartier-Kastler E, Del Popolo G, Kramer G, et al. EAU guidelines on neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2009;56:81–8.

Krebs J, Wollner J, Pannek J. Risk factors for symptomatic urinary tract infections in individuals with chronic neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Spinal Cord 2016;54:682–6.

Brolliar SM, Moore M, Thompson HJ, Whiteside LK, Mink RB, Wainwright MS, et al. A Qualitative Study Exploring Factors Associated with Provider Adherence to Severe Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury Guidelines. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:1554–60.

Lanig IS, New PW, Burns AS, Bilsky G, Benito-Penalva J, Bensmail D, et al. Optimizing the management of spasticity in people with spinal cord damage: a clinical care pathway for assessment and treatment decision making from the ability network, an international initiative. Arch Phys Med Rehabilit. 2018;99:1681–7.

Cardenas DD, Moore KN, Dannels-McClure A, Scelza WM, Graves DE, Brooks M, et al. Intermittent catheterization with a hydrophilic-coated catheter delays urinary tract infections in acute spinal cord injury: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. PM R 2011;3:408–17.

De Ridder DJ, Everaert K, Fernandez LG, Valero JV, Duran AB, Abrisqueta ML, et al. Intermittent catheterisation with hydrophilic-coated catheters (SpeediCath) reduces the risk of clinical urinary tract infection in spinal cord injured patients: a prospective randomised parallel comparative trial. Eur Urol. 2005;48:991–5.

Li L, Ye W, Ruan H, Yang B, Zhang S, Li L. Impact of hydrophilic catheters on urinary tract infections in people with spinal cord injury: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabilit. 2013;94:782–7.

Bermingham SL, Hodgkinson S, Wright S, Hayter E, Spinks J, Pellowe C. Intermittent self catheterisation with hydrophilic, gel reservoir, and non-coated catheters: a systematic review and cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ 2013;346:e8639.

Shamout S, Biardeau X, Corcos J, Campeau L. Outcome comparison of different approaches to self-intermittent catheterization in neurogenic patients: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 2017;55:629–43.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms S. Jonescu, Trauma Case Manager, Royal Perth Hospital, and Ms Anne Watts, Nurse Unit Manager, Fiona Stanley Hospital, for distributing study packs to relevant staff positions. Thank you also to Ms S. Knape, Registered Nurse, for professional and effective independent facilitation of study focus groups.

Funding

Project Grant (number: N/A), Neurotrauma Research Program, Perron Institute for Neurological and Translational Science, Western Australia. The University of Western Australia (in-kind funding via staff salary support).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LG & SD: Grant writing, study design, project oversight, data collection and analyses, paper, table preparation. GK: Data collection and analyses, intellectual input on paper. GK, DG, PB, AW, JB, JM: Intellectual input on study design and focus group questions; review, editing and approval of paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All applicable Institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of data from consenting hospital staff participants were followed. The South Metropolitan Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee provided ethical approval (16-148).

Informed consent

All participants (Clinicians) were provided with a Participant Information and Consent Form requiring their signatures.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goodes, L.M., King, G.K., Goodwin, D.M. et al. Barriers and facilitators to optimising inpatient bladder management after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 58, 1291–1300 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0487-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0487-6