Abstract

Study design

Qualitative exploratory study.

Objectives

Pressure injuries (PIs) are a major secondary condition occurring after spinal cord injuries (SCI). Optimization of outpatient and community care may be a promising approach to better support community-dwelling individuals with SCI in preventing PIs. The aim of this study was to examine the experiences of individuals with SCI, family caregivers and health professionals (HPs) in using or providing outpatient and community services for early treatment and prevention of PIs in SCI.

Setting

Switzerland.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews with a sample of Swiss residents community-dwelling individuals with SCI (n = 20), family caregivers (n = 5) and HPs (n = 22) were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

General practitioners (GPs), home care providers, SCI-specialized outpatient clinics and an SCI-specialized nursing service are involved in the prevention and early treatment of PIs. Our findings show that the needs of individuals with SCI are not fully met: outpatient and community care is often fragmented, mono-professional and non-specialized, while persons with SCI and HPs prefer coordinated, inter-professional and specialized services for preventing and treating PIs. Our findings also highlight the challenges faced by HPs in providing care to individuals with SCI in the community.

Conclusions

Although there seems to be a gap in service provision, there is the potential for improvement by better integrating the different providers in a network and structuring their collaborations. Concrete suggestions are: systematizing knowledge transfer to home care providers and GPs; redefining the role of involved HPs and individuals with SCI and reinforcing the role of the SCI-specialized nursing service.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a rare and complex health condition including loss or changes of motor and sensation functions as well as the loss of autonomous regulation of the body [1]. Pressure injuries (PIs) are a major secondary condition occurring after SCI that can be life-threatening [2, 3]. The treatment of severe PIs requires long hospital stays and often surgery [4], leading to high treatment costs [2].

Prevention of PIs remains a challenge due to multiple risk factors, such as age, years since the injury and extent of lesion, as well as lifestyle [5, 6]. According to the Canadian Best Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers in People with SCI and to the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, many PIs may be preventable [7]. Moreover, evidence shows that early treatment of superficial PIs is effective in avoiding their worsening into severe PIs [8]. Despite existing recommendations and education programs, many persons with SCI will still develop severe PIs during their lifetime [9,10,11]. One of the reasons is that prevention of PIs requires daily commitment, which includes many preventive actions that individuals with SCI must carry out and that need to be incorporated into the person’s lifestyle to be sustainable [12, 13].

In this endeavour, the optimization of outpatient and community healthcare services may be a promising approach to better support community-dwelling individuals with SCI. Indeed, a robust system of primary care, characterized by an annual comprehensive health evaluation, multidisciplinary follow-ups and access to disability-specific expertise, is associated with good health outcomes for individuals with SCI [14]. In Switzerland, a variety of outpatient and community healthcare services for persons with SCI are available and frequently used. Research shows that individuals with SCI consult general practitioners (GPs) twice as often and outpatient centres six times more often, than the general population does [15]. One reason may be that individuals with SCI prefer to go to a GP, if the SCI-specialized centre is not offered in their linguistic region [15]. Regionally organized home care services are used by 88% of the population with SCI [16]. Furthermore, a small SCI-specialized nursing service composed of ten nurses offers expert support and education, home visits and phone consultations countrywide. With the exception of the outpatient clinics and one nursing service, these services are not specialized in SCI. Besides, they are not automatically activated after initial rehabilitation, and individuals with SCI play a key role in deciding which services to engage. Only the SCI-specialized outpatient clinics invite individuals with SCI for a yearly check-up.

A better understanding from the perspective of service users and providers of outpatient and community care may provide insights on how the Swiss healthcare system is meeting the needs of community-dwelling individuals with SCI for prevention and treatment of PIs. The aim of this study is to examine the experiences of individuals with SCI, family caregivers and HPs in using or providing outpatient and community services to prevent or treat PIs in SCI.

Methods

This paper presents a qualitative exploratory study using semi-structured interviews. The design was chosen to examine the experiences of service users and service providers [17].

Sampling and recruitment of participants

We recruited a sample of Swiss residents with SCI, family caregivers and HPs. Eligibility criteria for all participants included: being >18 years of age and speaking one of the official Swiss languages fluently. Specific inclusion criteria for individuals with SCI were that they have lived in the community more than 5 years. In addition, we identified individuals having had none, one or several severe PIs. Considering the major support that many family members offer, we also recruited a convenience sample of family caregivers to complement the perspective of individuals with SCI. The specific inclusion criterion for HPs was being involved in the care of individuals with SCI. We purposively sampled participants working in different settings (inpatient, outpatient and community care) and in different regions of Switzerland (i.e. in different cantons, in urban and rural areas).

Recruitment was conducted with the collaboration of the four Swiss specialized centres for SCI acute care and rehabilitation, and by relying on intermediaries and wheelchair clubs. Potential participants among the HPs were contacted by telephone or email, whereas individuals with SCI and their caregivers were invited to participate by their HPs, and were contacted by the researchers only by agreement. Additional potential participants were identified thanks to a snowballing technique (i.e. individuals with SCI suggesting that their GPs or home care providers be interviewed, or HPs from SCI-specialized clinics suggesting names of other HPs working in the community) [18]. Individuals who expressed an interest in participating were contacted, study information was sent to them and an interview was scheduled.

Data collection and analysis

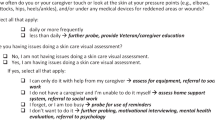

One researcher conducted all individual face-to-face semi-structured interviews. The interview topic guide was developed in collaboration with an inter-professional expert group. Interviews with individuals with SCI aimed at exploring their experience with PIs—knowledge and application of preventive measures, as well as the use of healthcare services for the prevention and treatment of PIs. Caregivers were asked similar questions, with a focus on their role in the prevention and treatment of PIs. Interviews with the HPs aimed at capturing the potential benefits and challenges of collaboration with patients and of the coordination of care to improve prevention and (early) treatment of PIs. Sample questions are presented in Table 1. Data were collected until thematic saturation was reached.

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, and analysed using thematic analysis. Thematic analysis was used to identify and interpret patterns, called themes, within the dataset [18]. Themes were developed by reading the interviews and assigning codes to text segments that captured something relevant in relation to the research question. The codes reflecting different aspects of a same phenomenon were collated in a theme. The themes were then reviewed by constantly comparing the excerpts among them and with those of other themes.

We used investigator triangulation to increase the trustworthiness of our findings [19]: NL developed preliminary codes and CZ reviewed the coding of half of the interviews (i.e. accepting the coding as performed by NL, suggesting a new code for the same excerpt or new codes for additional excerpts). This approach was useful to generate and examine multiple interpretations of data and to find convergence [20, 21]. As suggested by Lincoln and Guba [19], to ensure the fit between data and their interpretation, the findings were also discussed with other members of the research team. Furthermore, notes were taken to keep track of the rationale for decisions (i.e. methodological decisions), and a journal was kept by NL and CZ to record impressions and reflections [19]. The interviews were analysed in the original language and excerpts were translated only for the purpose of scientific publications. The software MAXQDA© (version 12.2.0) was used to organize and store data.

Results

The final sample included 47 participants—20 were persons with SCI, 5 were family caregivers and 22 HPs. Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 2.

The findings depict the experiences of individuals with SCI, caregivers and HPs with the outpatient and community care services to prevent and treat PIs. Two core themes were identified: the service users’ preference for expertise and the difficulty of providing adequate services in the community. Sample quotes are presented in Table 3.

Service users’ preference for expertise

Individuals with SCI stressed that, when it came to preventing and treating PIs, SCI-specialized knowledge was fundamental. Hence, they tended to seek out the support of and place their trust in HPs who had expertise in the field.

“I’d rather travel halfway around the world to see an SCI-expert.”

Most participants reported having first contacted an SCI-specialized centre or one of their outpatient clinics in the case of a PI. Some would rather make a long trip to reach the SCI-specialized centre than go to a closer general hospital without SCI expertise (Q1). Despite this preference for experts, all SCI-specialized physicians underscored that patients often made an appointment at the SCI-specialized centre only when the PI was already severe (Q2). One reason may have been that, as mentioned by some participants, distance presented an obstacle to their use of the service (Q3). Calling and digital transmission of photos were mentioned by one family caregiver as a reliable and appreciated alternative for seeking expert advice (Q4). In line with this preference for experts, the SCI-specialized nursing service was highly appreciated by all participants who had experienced its support: they valued its expertise in SCI and connections to the SCI-specialized centres, as well as home visits (Q5).

“I don’t need experiments.”

The limited knowledge of home care providers and GPs appeared to be a reason for their limited involvement in the prevention and care of PIs. While some participants described a well-established cooperation with their home care providers, others reported a feeling of distrust and the need to instruct them (Q6). Likewise, several individuals with SCI perceived themselves as more knowledgeable than GPs with regard to the prevention and treatment of PIs: they reported visiting GPs mostly for general conditions or for refilling prescriptions, and not specifically for PIs (Q7). Only two interviewees valued the advice of their GPs, but it emerged that their GPs had previous working experience in a specialized centre for SCI rehabilitation. It was not only the persons with SCI who considered that GPs generally had insufficient knowledge on the topic of PIs in SCI; the specialized HPs and the GPs themselves acknowledged their limited experience and preferred to leave the task to more experienced HPs (Q8). Indeed, according to the SCI-specialized HPs, the limited knowledge of some home care providers and GPs about SCI complications may have sometimes negatively affected the patient’s health (Q9).

The challenges of providing adequate community services

The analysis showed that HPs faced several challenges in providing care to individuals with SCI in the community.

“There is always a different nurse.”

More than half of the interviewed individuals with SCI and family caregivers had experiences with home care services. Many reported that their availability and turnover were suboptimal for adequately preventing and treating PIs. They reported that big nursing teams had more difficulties in judging and treating early stage PIs because effective monitoring of the skin over time is better done consistently by one person. Moreover, high staff turnover was also considered problematic by some participants because new staff members would not have the required SCI-specific knowledge (Q10). Other participants complained about the inflexible working hours of home care services, which could accommodate only in a limited way their lifestyle, needs and habits, with appropriate implementation of preventive measures (Q11). Several SCI-specialized HPs also confirmed these limitations of the home care service providers (Q12).

“We have to work with what we have in peripheral areas.”

Some HPs from the community services pointed out that, due to the limited number of specialized clinics in Switzerland and their concentration (three out of four) in the German-speaking region, in peripheral regions they tended to treat more complex cases and looked for other solutions to cope with the lack of specialized services (Q13).

“They are few and only work on call.”

The nurses of the SCI nursing service reported working in strict collaboration with the SCI-specialized centres and considered that being the contact person for HPs and patients could improve case management (Q14). This was confirmed by the HPs working in the specialized centres, who reported that the nurses of the counselling service were their eyes in the patients’ home (Q15). However, some HPs considered that the small number of nurses working for this service partially limited their potential for coordinating care (Q16). Moreover, the SCI nursing service needed to be activated by the patients, i.e., if they did not contact the nurses, the nurses could not provide their services (Q17).

“We have to know and respect each other’s work.”

Some participants stated that, for inter-professional collaboration to happen there needs to be knowledge of the available services on the part of all HPs. However, from what was reported by other participants, this did not seem to always be the case in our sample. For instance, not all home care providers and GPs knew of the SCI-specialized nursing service (Q18). Among the HPs working in community care, those with extensive experience in rehabilitation valued having a good network (Q19). In addition to the mutual knowledge, acceptance and respect for the expertise of other professionals were essential for inter-professional collaboration. It required tolerance for other ways of working, insofar as they did not harm the patient (Q20).

“We try to develop a common language and bridge the knowledge gap.”

The SCI-specialized HPs recognized the efforts exerted in developing a common language and bridging the knowledge gap of the home care providers, by regularly organizing courses for HPs assisting individuals with SCI (Q21). These offers for further SCI-education were well attended and appreciated by home care providers (Q22). In the process, these courses also helped mitigate potential conflicts between home care providers and individuals with SCI, by explaining that individuals with SCI are trained to self-manage their condition and that it is important to respect their know-how (Q23). Complementary to the training, the HPs pointed out the potential of the SCI-specialized nursing service to act as a key advisor for community services due to their knowledge of SCI-specific environmental and behavioural challenges (Q24).

Discussion

Outpatient and community healthcare services are central players in supporting people with SCI and their caregivers in the daily management of SCI and in the prevention of secondary conditions. In spite of this, some services seem to be more valued than others are when it comes to the prevention and treatment of PIs, a very common and severe complication. Thanks to its SCI-specialized knowledge and good connections with the specialized clinics, the SCI-specialized nursing service was considered a popular contact point by people with SCI and their caregivers, and a valid partner by other HPs. In contrast, GPs and home care providers were often criticized for their lack of expertise, and the latter also for the structural limitations of their service. SCI-specialized HPs reported that individuals with SCI often contacted the specialized services only when the PIs were already severe.

To sum up, a handful of services are involved in the prevention and early treatment of PIs in community-dwelling individuals with SCI in Switzerland. Our findings show that they do not always respond adequately to the needs of individuals with SCI: the various providers are not integrated into a network and often their collaborations are unstructured. Further, patients with SCI and HPs express a preference for coordinated, inter-professional and specialized services for preventing and treating PIs. In the reality, outpatient and community care are frequently fragmented, mono-professional and non-specialized. In the following, we discuss the extent of this gap in service provision, relate it to previous studies and reflect on the practical implications for the development of services that better meet the needs of individuals with SCI. By focusing on how to improve the services, our findings complement the existing literature, which emphasizes the role of self-management and personal responsibility of individuals with SCI in preventing complications [8, 22, 23].

Our study illustrates the problem of the lack of integration of care, which is already well-known in the fragmented Swiss health care system. Different from many other health conditions [24], in SCI the GPs do not seem to represent the first contact and are not in charge of the coordination of care, when it comes to the prevention and treatment of PIs. The connection between specialized and non-specialized services is established on a service-to-service level at discharge from rehabilitation (e.g. through the training of home care providers by specialized HPs), but a structured long-term collaboration is not formally established. In addition, the team of home care providers is often unstable, making an efficient exchange of information challenging in a system without integrated, shared e-health information. Consequently, SCI-specific expertise seems to be missing in the community. Indeed, GPs often have limited experience with PIs and specifically PIs in individuals with SCI, or they are unfamiliar with the complex interventions to reduce the incidence of PIs [4, 8]. The reason may be that SCI requires highly specialized knowledge and experience, which are difficult to build outside a specialized clinic and in the absence of recurrent contact with persons with SCI. Likewise, the competence of home care providers for preventing and treating PIs in SCI is limited. This is evidenced in studies in other specialized fields, such as heart failure or pain management, highlighting certain deficits in the knowledge of the nurses [25, 26].

GPs and home care providers have a general knowledge and expertise base to support individuals with all kinds of conditions. Therefore, expecting them to also provide specialized expertise in treating patients with SCI may not be realistic. However, it is essential to offer training and support to non-specialized HPs in order to improve the continuity of care and case management for individuals with SCI. This is even more important considering that individuals with SCI in Switzerland would rather go to GPs if the SCI-specialized service is not offered in their linguistic region, and that the treatment of PIs is currently one of the main reasons for being treated outside the residential canton [27].

In light of the above, we therefore suggest to, first, clarify the capacity of each involved partner—patient, family caregiver, GP, home care provider, specialized nurse and doctor. Being aware of the advantages and disadvantages of the different services could allow a clearer allocation of tasks and responsibilities. Second, in line with Cox et al. [28], we suggest an expanded inter-professional collaboration between SCI-specialized services and non-specialized services to improve the long-term care of individuals with SCI. This could start with a systematization of knowledge transfer to home care providers and GPs who are involved in the care of individuals with SCI. On the one hand, home care providers could take full advantage of the training offered by the SCI-specialized clinics. This also implies that each team caring for a person with SCI has enough trained personnel and that this specialized knowledge is taken into consideration when organizing shifts, to ensure that a trained person is available for serving the person with SCI. On the other hand, the SCI-specialized nursing service could ensure further education and support in the long-term and in situ for the home care providers. The experience of the inter-professional primary care-based Mobility Clinic in Canada is an encouraging example of how to improve primary care beyond just better physical accessibility for persons with SCI [29]. Last, we favour a reinforcement of the role of the SCI-specialized nursing services. As Williams highlighted, nurses can be change agents to promote more patient-centred care [30].

Nevertheless, the nurses of the SCI-specialized service currently suffer from limitations that hinder their role as case manager and coordinator of the outpatient care for people with SCI. The service is not automatically involved in community care—it only becomes involved on the initiative of the SCI-specialized HPs or of the patients themselves. Besides, its mandate is limited due to lack of financing. In order to help close the above-mentioned gap, the scope and support of the SCI-specialized service should be expanded. Concretely, this could enhance the timely referral to the centres and help overcome the current problem of delayed consultations.

Our study has certain limitations. The qualitative design generated rich and multi-perspective data, achieving thematic saturation, though limitations to the generalizability of our findings need to be acknowledged. To increase our chances of reaching a diversified population, we recruited our participants through different channels (SCI rehabilitation centres, wheelchair clubs and HPs). In spite of this, a self-selection bias cannot be excluded. Moreover, the final sample included many more specialized than non-specialized HPs, as it was difficult to identify non-specialized HPs who had experience with individuals with SCI. Further, although two researchers worked on the interview transcripts and regularly met to discuss alternative interpretations and refine the codes, no systematic independent coding was performed.

The current study provides an in-depth view of the potential weaknesses in the way the Swiss healthcare system responds to the needs of community-dwelling individuals with SCI for the prevention and early treatment of PIs. We suggest that outpatient and community healthcare services could be improved by three means to better support individuals with SCI in prevention and early treatment of PIs. First, the capacity of each involved partner should be clarified; second, inter-professional collaboration between SCI-specialized services and non-specialized services should be expanded; and third, the role of the SCI-specialized nursing services should be reinforced. Overall, in Switzerland there seems to be a service provision gap, but also the potential to improve the involvement of HPs in the prevention and early treatment of PIs in community-dwelling individuals with SCI.

Data availability

The transcripts of the interviews analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on request. Transcripts will be provided in the original language (mostly German).

References

Bickenbach J, Biering-Sørensen F, Knott J, Shakespeare T, Stucki G, Tharion G, et al. Chapter 1: understanding spinal cord injury. In: Bickenbach J, et al. editors. International perspectives on spinal cord injury. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

DeVivo M, Farris V. Causes and costs of unplanned hospitalizations among persons with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2011;16:53–61.

Brinkhof MWG, Al-Khodairy A, Eriks-Hoogland I, Fekete C, Hinrichs T, Hund-Georgiadis M, et al. Health conditions in people with spinal cord injury: contemporary evidence from a population-based community survey in Switzerland. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48:197–209.

Regan MA, Teasell RW, Wolfe DL, Keast D, Mortenson WB, Aubut JA. A systematic review of therapeutic interventions for pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:213–31.

Marin J, Nixon J, Gorecki C. A systematic review of risk factors for the development and recurrence of pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:522–7.

Gelis A, Dupeyron A, Legros P, Benaim C, Pelissier J, Fattal C. Pressure ulcer risk factors in persons with spinal cord injury part 2: the chronic stage. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:651–61.

Black JM, Edsberg LE, Baharestani MM, Langemo D, Goldberg M, McNichol L, et al. Pressure ulcers: avoidable or unavoidable? Results of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Consensus Conference. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2011;57:24–37.

Jackson J, Carlson M, Rubayi S, Scott MD, Atkins MS, Blanche EI, et al. Qualitative study of principles pertaining to lifestyle and pressure ulcer risk in adults with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:567–78.

Garber SL, Rintala DH, Hart KA, Fuhrer MJ. Pressure ulcer risk in spinal cord injury: predictors of ulcer status over 3 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:465–71.

Fuhrer MJ, Garber SL, Rintala DH, Clearman R, Hart KA. Pressure ulcers in community-resident persons with spinal cord injury: prevalence and risk factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:1172–7.

Chen Y, Devivo MJ, Jackson AB. Pressure ulcer prevalence in people with spinal cord injury: age-period-duration effects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1208–13.

Munce SE, Webster F, Fehlings MG, Straus SE, Jang E, Jaglal SB. Perceived facilitators and barriers to self-management in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:48.

Fogelberg D, Atkins M, Blanche EI, Carlson M, Clark F. Decisions and dilemmas in everyday life: daily use of wheelchairs by individuals with spinal cord injury and the impact on pressure ulcer risk. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2009;15:16–32.

McColl MA, Aiken A, McColl A, Sakakibara B, Smith K. Primary care of people with spinal cord injury: scoping review. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:1207–e635.

Ronca E, Scheel-Sailer A, Koch HG, Gemperli A.for the SwiSCI Study Group.Health care utilization in persons with spinal cord injury. Part 2: determinants, geographic variation and comparison with the general population. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:828–33.

Gemperli A, Ronca E, Scheel-Sailer A, Koch HG, Brach M, Trezzini B, et al. Health care utilization in persons with spinal cord injury. Part 1:outpatient services. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:823–7.

Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data: Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011.

Clarke V, Braun V. Teaching thematic analysis: overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist. 2013;26:120–3.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1985.

Creswell JW. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014.

Johnson RB. Examining the validity structure of qualitative research. Education. 1997;118:282–92.

Kruger EA, Pires M, Ngann Y, Sterling M, Rubayi S. Comprehensive management of pressure ulcers in spinal cord injury: current concepts and future trends. J Spinal Cord Med. 2013;36:572–85.

Clark FA, Jackson JM, Scott MD, Carlson ME, Atkins MS, Uhles-Tanaka D, et al. Data-based models of how pressure ulcers develop in daily-living contexts of adults with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1516–25.

Peytremann-Bridevaux I, Burnand B, Cassis I, Nolte E. Assessing chronic disease management in European health systems: country reports. In: Nolte EKC, editor. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2015.

Delaney C, Apostolidis B, Lachapelle L, Fortinsky R. Home care nurses’ knowledge of evidence-based education topics for management of heart failure. Heart & Lung. 2011;40:285–92.

Glajchen M, Bookbinder M. Knowledge and perceived competence of home care nurses in pain management: a national survey. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2001;21:307–16.

Ronca E, Scheel-Sailer A, Koch HG, Metzger S, Gemperli A. Inpatient migration patterns in persons with spinal cord injury: a registry study with hospital discharge data. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:259–68.

Cox RJ, Amsters DI, Pershouse KJ. The need for a multidisciplinary outreach service for people with spinal cord injury living in the community. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15:600–6.

Milligan J, Lee J. Enhancing primary care for persons with spinal cord injury: more than improving physical accessibility. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39:496–9.

Williams S. Improving the continuing care for individuals with spinal cord injuries. Brit J Nurs. 2005;14:161–5.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the participants for their time and engagement. We also thank Nadja Münzel for her comments on an earlier version of the paper, and Hans Georg Koch for his assistance in the recruitment of study participants. Thank you also to Lisa Adey, who carefully checked the translation of all quotes from the interviews.

Funding

This project was supported by the Suva, the Swiss National Accident Insurance Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NL contributed to the preparation of the protocol for the Ethics Committee, recruited the participants, conducted and transcribed the interviews. She also contributed to data analysis and publication drafting. CZ was involved in the design of the study, supervised data collection, mainly contributed to data analysis and interpretation of the findings, as well as to drafting, revising and finalizing the manuscript for submission. SE was involved in interpreting the findings, drawing implications for practice as well as in drafting, revising and finalizing the paper for submission. ASS was involved in developing the study protocol, interpreting the findings, drawing implications for practice as well as drafting the paper. GS, SR and MB developed the study protocol, provided feedback and approved the manuscript draft. AG provided feedback on the manuscript draft. GS, MB, AG, ASS and SE were also part of the Expert Advisory Group for this project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical treatment of human volunteers were followed throughout the study. The study obtained ethical approval from the regional committee of north-western and central Switzerland (Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz, reference number EKNZ 2015-311).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zanini, C., Lustenberger, N., Essig, S. et al. Outpatient and community care for preventing pressure injuries in spinal cord injury. A qualitative study of service users’ and providers’ experience. Spinal Cord 58, 882–891 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0444-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0444-4