Abstract

Study design

Comparative study of survey self-report data.

Objectives

To compare individuals living with spinal cord injury (SCI) in Switzerland to the general population in terms of mental health, quality of life, self-efficacy, and social support.

Setting

Community, Switzerland.

Methods

Data from the 2017 community survey of the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Cohort Study were compared to data from two matched (1:3 nearest neighbor propensity score) general population surveys collected in the same year. Measures of mental health (mental health index, psychological distress item, vitality scale, and energy item), quality of life (WHOQOL-BREF item), self-efficacy (General Self-Efficacy Scale item), and social support (items of relationship satisfaction, living alone, and marital status) were compared across datasets using regression adjusted for non-response correction weights. The analyses were then replicated in subgroups defined by sociodemographic, lesion-related, and secondary health issues factors.

Results

Individuals with SCI had significantly higher psychological distress and poorer mental health, vitality, energy, and quality of life than the general population, with medium to large effect sizes (Cohen’s d: 0.35–1.08). They also had lower self-efficacy and relationship satisfaction, lived more frequently alone, and were more frequently single. Individuals with less severe secondary health issues reported mental health and quality of life more similar to the general population than those reporting more severe issues.

Conclusions

This study highlights a significant long-term impact of SCI on well-being and psychosocial resources, underlining the need for ongoing biopsychosocial care beyond inpatient rehabilitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Even if individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) present different trajectories of mental health and QoL [1], they have been shown to have, on average, lower mental health and quality of life (QoL) than the general population in various European, American, and Asian countries [2, 3]. Theoretical models (e.g., the Spinal Cord Injury Adjustment Model [4]) suggest that psychosocial resources such as self-efficacy, dispositional optimism, and social support explain differences in mental health and QoL. In line with this, empirical research has confirmed that higher self-efficacy and self-esteem are associated with better mental health and QoL of individuals with SCI [5]. Similarly, a systematic review showed that social support, both its quantity (network size, presence and/or availability of social support sources) and its quality (appraisal of social support resources) is associated with better mental health and QoL [6]. However, fewer studies have investigated the impact of SCI onset on these psychosocial resources. There is evidence that purpose in life, self-esteem, and self-efficacy can decrease in the first months following SCI [7, 8]. As for social resources, individuals with SCI have been shown to be more frequently single [9], to have higher divorce rates [10], to report higher loneliness [9], and to have lower evaluation of the social support received [11].

The existence of inter-individual differences in psychological adaptation to SCI does not negate the importance of investigating general trends to guide decision making in and provision of health care services. In that regard, many studies comparing individuals with SCI to the general population are limited by the use of unmatched samples which does not account for demographic differences such as more males and elderly in the SCI population [12]. Given that older individuals or males generally have a better mental health than younger individuals or females [13], demographic differences must be controlled for by using matched samples when comparing individuals with SCI to the general population. Moreover, more studies comparing individuals with SCI to the general population in countries with different healthcare system are needed to evaluate the potential impact of different health policies. In contrast to other countries, individuals living in Switzerland are obliged to pay for an insurance that grants a pension to individuals who cannot work due to disability. Thus, analyses of the relative mental health, QoL, and psychosocial resources of individuals with SCI are needed in the Swiss context.

The main objective of this study was to investigate differences in mental health, QoL, self-efficacy, and social support between people living with SCI in Switzerland and matched samples from the national general population. Based on the research conducted in other countries, we hypothesized that on average people with SCI would present with lower mental health, QoL, self-efficacy, and social support than the general population.

Sociodemographic factors such as sex, age, and occupation [13, 14], lesion-related characteristics such as lesion level, completeness, etiology, and time since injury, and the severity of secondary health issues [15] can influence mental health and QoL of individuals with SCI. Consequently, a secondary aim of this study was to explore whether differences observed between individuals with SCI and the general population would hold for different subgroups defined by sociodemographic, lesion-related, and secondary health issues factors.

Methods

Design

This was a cross-sectional study comparing survey data of individuals with SCI to that of matched samples selected from two Swiss general population surveys.

Sample

This study used the second Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Cohort Study (SwiSCI) community survey (survey 2017 [16]) as well as the general population Swiss Household Panel (SHP) and the Swiss Health Survey (SHS) datasets. As some SwiSCI variables were assessed in the SHP, but not in the SHS or vice versa, two general population datasets were used to increase the number of outcomes that could be compared.

The SwiSCI is a population-based longitudinal cohort study performed by Swiss Paraplegic Research. The second SwiSCI community survey was conducted between March 2017 and March 2018 and included two questionnaires with the second questionnaire sent after four to six weeks to the individuals who filled in the first one (response rate = 38.6% and 32.7% respectively) [16]. Each questionnaire could be completed online, paper-and-pencil, or by face-to-face or telephone interview. Eligible participants were individuals 16 years or older living in the community with a permanent residence in Switzerland and a diagnosed SCI. Individuals presenting “congenital conditions leading to SCI (e.g., spina bifida), those with neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., multiple sclerosis or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) and Guillain-Barré syndrome” [16] were not eligible. Data were collected in collaboration with the four specialized SCI rehabilitation centers in Switzerland, the national organization for persons living with SCI (Swiss Paraplegic Association), and an SCI-specialized home care organization (ParaHelp). As shown in Fig. 1, the sample for this study included all participants who completed the two questionnaires of the second SwiSCI community survey (N = 1294).

The SHP is a yearly national survey conducted by the Swiss Center of Expertise in the Social Sciences (FORS) using telephone interviews. It uses a nationally representative panel of all individuals living in private households with random sampling stratified by major geographic regions. Exclusion criteria are: younger than 14 years or not permanently living in a private household in Switzerland. This study used the 2017 individual questionnaire data collected between September 2017 and February 2018 (N = 4232).

The SHS is a nationally representative survey conducted every five years by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office using a telephone interview followed by a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. Participants are selected through a random draw stratified by cantons’ size of households based on the cantonal population registries. Exclusion criteria are being younger than 15 years and not permanently living in a private household in Switzerland. This study used the 2017 data collected between January and December (N = 22,134).

Sample harmonization

To lower bias resulting from differences in sampling procedures, participants younger than age 16 were excluded from the SHP and SHS, and participants living in an institution (i.e., elderly housing or nursing homes) or not indicating their living situation were excluded from the SwiSCI (see Fig. 1). Consequently, the final sample of this study includes 1235 SwiSCI participants.

Measures

The outcomes were selected from the SwiSCI questionnaire [17] based on conceptual relevance and being assessed in the SHP, the SHS, or both. Mental health was assessed with a psychological distress single item [18], an energy single item [18], and the mental health index and vitality scale of the SF-36 [13, 19]. Some authors suggest that mental health index scores lower than 72 indicate mental health problems and severe mental health problems when below 60 [20]. QoL was assessed with a single item of the WHOQOL-BREF [21]. Regarding psychosocial resources, self-efficacy was measured with one item from the General Self-Efficacy Scale [22]. Moreover, the relationship satisfaction item of the WHOQOL-BREF [21] assessed quality of social support, and quantity of social support was assessed with a living alone or not item and marital status. The item wordings, missing data rates, and internal consistency of these measures are described in Table 1.

To explore which factors influence the differences between individuals with SCI and the general population, sociodemographic factors (sex, age, having a paid job or not, and having a productive activity or not), lesion-related factors (level, completeness, etiology, and years since injury; retrieved from medical records or self-reported if the record was not available), and the severity of three separate secondary health conditions (pain, bladder, and bowel issues) were assessed as described in Table 1.

Variable harmonization

The five outcome variables relating to QoL, self-efficacy, and social support had different scaling in the SwiSCI survey than in the general population surveys. Moreover, self-efficacy was assessed with one item in the SwiSCI survey (“When I am confronted with a problem, I can usually find several solutions.”) and another item deemed equivalent in the SHS survey (“There is no way I can solve some of the problems I have.” [23]). Thus, a variable harmonization process based on existing guidelines [24], logical thinking, and inter-researcher consensus was performed; the results are available in Supplementary Table 1. Examples of harmonization are reversing a scale (e.g., QoL), recoding a 0–10 scale into a 1–5 scale (e.g., relationship satisfaction), or merging categories (e.g., marital status).

Analysis

Data matching

Given that the three surveys might present unequal representations of certain groups of individuals due to different sampling techniques, we used a matching technique to balance the distribution of some covariates between the SCI and general population samples. As described in Supplementary Information 1 and 2, The STATA psmatch2 command was used in three rounds to enable a 1:3 nearest neighbor matching without replacement based on propensity scores (i.e., probability to present an SCI based on individual covariates). For each individual in the SwiSCI dataset, three individuals from both the SHP and SHS datasets were matched according to similarity in terms of sex, age, language of questionnaire (German/French/Italian), and country of birth (Switzerland/other).

Multiple imputation

SHP and SHS participants with missing information on any of the outcomes (mental health, QoL, and psychosocial resources listed in Table 1) or matching variables (sex, age, language of questionnaire, and country of birth) were excluded before the matching procedure. For the SwiSCI dataset, multiple imputation with chained equations was used to impute missing information on the outcomes at the item-level (20 imputed datasets). The matching variables, the lesion characteristics (level, completeness, etiology, and years since injury), and the non-response correction weights (described elsewhere [16]) were entered as auxiliary variables.

Main analyses

To compare the SCI sample to the matched general population samples, regression analyses adjusted for non-response correction weights were run using the imputed datasets. Ordinary least squares regression was used for the continuous outcomes (mental health, psychological distress, vitality, energy, QoL, self-efficacy, and relationship satisfaction) and logistic regression for the binary outcomes (living alone or not and dummy variables for marital status categories). Each outcome variable was tested in a separate regression model with a single binary independent variable (SCI vs general population) and no other covariate. Regression models had to be used, because multiple imputation and weight adjustment are not implemented for t or chi2 tests in the statistical program used for the analyses (Stata 16 [25]). However, ordinary least squares regressions with a single binary independent variable run independent sample t-tests. Also, the test for coefficient significance in logistic regressions with multiply imputed data are based on Student’s t distribution due to non-normality of the reference distribution. Thus, ts are consistently reported for significance tests, whereas for effect sizes, Cohen’s ds (small = 0.20, medium = 0.50, large = 0.80 [26]) and odds ratios are reported for the continuous and binary outcomes respectively. A conservative significance level of .01 was applied to avoid an increased chance of type I error due to multiple analyses applied to the same samples.

Subgroup analyses

The main analyses were replicated in different subgroups defined by: sex, age categories, having a paid job or not, having a productive activity (work, study, homemaker) or not, lesion level, completeness, and etiology (traumatic or non-traumatic), years since injury, and severity of pain, bladder, and bowel issues (described in Table 1). Individuals from the SwiSCI sample were classified into the different subgroups according to these sociodemographic, lesion-related, and secondary health issues factors. However, the individuals from the general population had no lesion-related or secondary health issues information and could not be classified into corresponding subgroups. Given that the matching procedure paired each individual from the general population sample to one SwiSCI individual based on their similarity on the matching variables (see also Supplementary Information 1), individuals from the general population samples were classified in the same lesion-related or secondary health issues subgroup as their paired SwiSCI individual. Due to smaller sample size, some reduction in statistical significance are to be expected when repeating the analyses in subgroups. For this reason and the sake of conciseness, we highlighted only the most salient results showing consistent trends across several outcomes and substantial effect size changes (>0.20) compared to the main analyses’ results.

Results

Data matching and descriptive statistics

After the previously described sample harmonization and matching procedure, the final SCI sample included 1235 participants matched to 3705 individuals from the SHP and 3705 individuals from the SHS (see Fig. 1). Post-tests estimating the effectiveness of the matching procedure showed a satisfactory reduction of the difference between the SCI and the general population samples as well as no significant difference between the SwiSCI and the matched general samples in terms of sex, age, language of questionnaire, and country of birth (see Supplementary Table 2).

The descriptive statistics of the three samples after matching are displayed in Table 2. One-way ANOVAs with post-hoc tests showed that individuals answering the SwiSCI questionnaires online reported significantly higher vitality, energy, QoL, and self-efficacy than individuals choosing the paper-and-pencil questionnaires (see Supplementary Table 3). All other comparisons of data collection methods within SwiSCI were non-significant (p > 0.05).

Comparisons between the final SCI sample and the excluded individuals (see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 4) showed that the 236 participants who did not return the second questionnaire had lower QoL, had more frequently a tetraplegic injury level and non-traumatic lesion, were less frequently born in Switzerland, and were more frequently living alone compared to the final SCI sample. Moreover, the 59 participants excluded for data harmonization reasons showed less self-efficacy and were more frequently female, older, not married, or widowed than the final SCI sample.

Main analyses

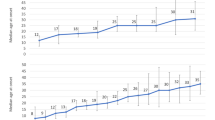

Results of the analyses comparing the final SCI sample to the matched general population samples are displayed in Fig. 2 and show significant differences on almost all outcomes studied. Individuals with SCI had significantly lower mental health, higher psychological distress, less vitality, less energy, and lower QoL compared to the matched samples. Cohen’s ds showed that the difference was large for mental health, vitality, and QoL (Cohen’s ds between 0.71 and 1.08) and medium for psychological distress and energy (Cohen’s ds = 0.37 and 0.35, respectively). According to the proposed cutoffs of the SF-36 mental health index, 33.9% of our SCI sample present mental health problems including 19.11% with severe problems, whereas the corresponding percentages in the general population were 11.0% and 4.7%.

Significance tests are reported as ts, because ordinary least square regressions (used for the continuous outcomes) with a unique binary independent variable run independent sample t-tests and the test for significance of multiple imputation logistic regressions (used for the binary outcomes) are based on Student’s t distribution. For effect sizes, Cohen’s ds (small = 0.20, medium = 0.50, large = 0.80 [26]) were calculated for the continuous outcomes and odds ratios are reported for the binary outcomes. Each outcome was tested in separated regression without covariates. Similarly, comparisons to SHS and SHP samples were run separately. Thus, 17 models were run in total. Note that the x-axes were truncated to increase readability (see Table 1 for the outcome variables’ range).

Regarding psychological resources, individuals with SCI reported significantly less self-efficacy, with a small effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.23). For social support, results showed that individuals with SCI report significantly lower relationship satisfaction, live more frequently alone, are more frequently single and less frequently married, with medium effect size for relationship satisfaction (Cohen’s d = 0.43) and small effect sizes for the other social support measures (odds ratios between 0.43 and 1.81). No difference was observed for the proportion of separated and widowed individuals.

Subgroups analysis

The analyses conducted in subgroups defined by sociodemographic factors (sex, age categories, having a job or not, and having a productive activity or not) as well as by lesion-related factors (years since injury, level, completeness, and etiology) yielded no marked and consistent differences as compared to the results from our main analyses (Supplementary Tables 5–12); this means that individuals with SCI reported lower mental health, QoL, self-efficacy, relationship satisfaction, and quantity of social support than the general population across all of the subgroups. However, the results in the subgroups defined by the severity of secondary health issues (pain, bladder, or bowel issues) differed substantially from those in the main analyses (Supplementary Tables 13–15). As displayed in Fig. 3, the individuals with SCI reporting none or insignificant secondary health issues presented mental health, QoL, and psychosocial resources more similar to the matched general population samples (i.e., lower effect sizes) than individuals reporting more severe secondary health issues. In particular for higher levels of pain, discrepancies become more and more prominent with increasing severity of the secondary health issue, as indicated by substantially increased effect sizes pointing to lower mental health, QoL, and psychosocial resources in individuals with SCI as compared to the general population.

ds are Cohen’s d with negative sign indicating lower means for the SCI sample than for to the general population sample. Small effect size (<0.20) are highlighted in light gray, medium effect sizes (between 0.20 and 0.50) in medium gray, and large effect sizes (>0.70) in dark gray. None Not experienced or insignificant issues, Mild Mild or infrequent issues, Moderate Moderate or occasional issues, Chronic Significant or chronic issues, NSCI sample size for SCI, NSHS/SHP sample size for SHS or SHP.

Discussion

Individuals living for many years with an SCI in Switzerland have, on average, poorer mental health, lower QoL and lower psychosocial resources than the general population. Thus, the results from this study are in line with previous European and American studies [2, 3]. The moderate to large effect sizes regarding mental health, vitality, and QoL indicate substantial differences between individuals with SCI and the general population. If we follow the advocated cut-offs for the SF-36 [27], our results indicate that 33.9% of the SCI sample presents mental health problems. These proportions are in line with literature showing that the majority of individuals display resilience after an SCI [1], but they are still alarming, because the proportion of the general population likely to have mental health problems is much lower (11.0%).

Individuals living with SCI reported lower self-efficacy compared to the Swiss general population, but the difference was small despite the important functioning limitations caused by an SCI. The observed lower self-efficacy might be due to individuals with SCI revising an exaggerated perception of mastery, which has been found for (non-disabled) people [28], because they experienced a very challenging life event. Confirming preliminary evidence from other countries [9,10,11], our results show that individuals with SCI are more isolated (living more frequently alone and more frequently single) and report lower relationship satisfaction than the general population. This underlines the need for more community interventions to increase social skills, network, and support of individuals living with SCI [29].

The subgroup analysis showed that the differences observed between individuals with SCI and the general population are not influenced by sociodemographic or lesion-related characteristics. However, individuals with SCI reporting less severe secondary health issues (and especially lesser or less frequent pain) present mental health, QoL, and psychosocial resources more similar to those of the general population than those reporting more severe secondary health issues. This suggests that the primary physical consequence of an SCI such as the loss of motor and sensory functions has a lower impact on mental health, QoL, and psychosocial resources than secondary health issues. These results imply that individuals living with SCI who report severe pain, bladder, and bowel issues should receive not only secondary health issues management, but also psychological support to overcome the psychosocial load of these conditions.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first comparing mental health and QoL of individuals with SCI to the general population in Switzerland. To the best of our knowledge, it is also the first study comparing psychosocial resources in the SCI and the general population. Moreover, the use of matched samples enhances comparability between the different datasets and reduces confounding biases.

Nevertheless, different datasets can never be perfectly comparable, because it is virtually impossible to control for every potential confounder. Whereas some outcomes could be directly compared across the three datasets, others differed in their response options (i.e., relationship satisfaction and marital status) or item wording (i.e., self-efficacy). This underlines the need for more cross-survey standardization of future data collection. In our study, two different self-efficacy items were deemed equivalent, but this can be contested. Thus, the comparison on some harmonized outcome variables (especially self-efficacy) should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, single item measures are commonly used in large surveys, because they alleviate the participant burden. However, single item measures might present low reliability [30], which could have biased our results.

Our results pertaining to social support are fragmented. Our measure of social support quality covers the overall relationship, but not the specific satisfaction with certain sources, while our social support quantity measures (living alone, marital status) cover only a limited spectrum of potential social support networks. Moreover, availability of social support sources does not necessarily imply that support is actually provided or helpful. For instance, being married can be detrimental, because marital dissatisfaction has been shown to be related to higher depression [31]. Future studies using better measures of social support are needed to confirm that individuals with SCI differ from the general population in terms of social resources. Similarly, future research should test how other psychological resources such as purpose in life or optimism differ between individuals with SCI and the general population.

The SwiSCI community survey presents rather low response rates that are in line with other SCI community surveys worldwide [16]. Thus, non-response correction weights were used in the analysis to reduce non-response bias [16]. Nevertheless, the SwiSCI participants excluded from this study because of questionnaire completion or data harmonization were significantly more vulnerable (i.e., older or lower QoL) compared to the sample analyzed. Consequently, our study might overestimate the mental health and QoL of the SCI sample meaning that the differences to the general population are even bigger than the ones reported. Finally, the possibility of answering the questionnaires online was only available in the SwiSCI survey. This option might attract a specific type of population and create different self-reporting biases, which limits the comparability between surveys.

Conclusion

Whether the average mental health and QoL of individuals living with SCI is indicative of clinical disorders or not, the significant differences with the general population with medium to large effect sizes argues for provision of ongoing care after inpatient rehabilitation. Such care should have a particular focus on secondary health issues management that includes psychological support.

Data availability

Owing to our commitment to SwiSCI study participants and their privacy, datasets generated during the current study are not made publicly available but can be provided by the SwiSCI Study Center based on reasonable request (contact@swisci.ch)

References

Bonanno GA, Kennedy P, Galatzer-Levy IR, Lude P, Elfström ML. Trajectories of resilience, depression, and anxiety following spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2012;57:236–47.

Post M, Van, Leeuwen C. Psychosocial issues in spinal cord injury: a review. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:382–9.

Williams R, Murray A. Prevalence of depression after spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:133–40.

Craig A, Tran Y, Middleton J. Theory of adjustment following severe neurological injury: evidence supporting the spinal cord injury adjustment model. Horiz Neurosc Res. 2017;29:117–39.

Peter C, Müller R, Cieza A, Geyh S. Psychological resources in spinal cord injury: a systematic literature review. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:188–201.

Müller R, Peter C, Cieza A, Geyh S. The role of social support and social skills in people with spinal cord injury—a systematic review of the literature. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:94–106.

Kunz S, Joseph S, Geyh S, Peter C. Perceived posttraumatic growth and depreciation after spinal cord injury: actual or illusory? Health Psychol. 2019;38:53–62.

van Leeuwen C, Edelaar-Peeters Y, Peter C, Stiggelbout AM, Post MWM. Psychological factors and mental health in persons with spinal cord injury: an exploration of change or stability. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47:531–7.

Tough H, Fekete C, Brinkhof MWG, Siegrist J. Vitality and mental health in disability: associations with social relationships in persons with spinal cord injury and their partners. Disabil Health J. 2017;10:294–302.

DeVivo MJ, La Verne NH, Richards JS, Go BK. Outcomes of post-spinal cord injury marriages. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:130–8.

van Leeuwen C, Post MW, van Asbeck FW, van der Woude LH, de Groot S, Lindeman E. Social support and life satisfaction in spinal cord injury during and up to one year after inpatient rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42:265–71.

Chen Y, He Y, DeVivo MJ. Changing demographics and injury profile of new traumatic spinal cord injuries in the United States, 1972–2014. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:1610–9.

Roser K, Mader L, Baenziger J, Sommer G, Kuehni CE, Michel G. Health-related quality of life in Switzerland: normative data for the SF-36v2 questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:1963–77.

Ottomanelli L, Lind L. Review of critical factors related to employment after spinal cord injury: implications for research and vocational services. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:503–31.

van Koppenhagen CF, Post MW, van der Woude LH, de Groot S, de Witte LP, van Asbeck FW, et al. Recovery of life satisfaction in persons with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehab. 2009;88:887–95.

Gross-Hemmi MH, Gemperli A, Fekete C, Brach M, Schwegler U, Stucki G, et al. Methodology and study population of the second Swiss national community survey of functioning after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00584-3.

The SwiSCI Study Group. SwiSCI study design: the community survey [Internet]. Nottwil: Swiss Paraplegic Research (SPF); 2020. https://swisci.ch/en/research-projects-home/study-design/community-survey.

Morselli D. Contextual determinants of hopelessness: investigating socioeconomic factors and emotional climates. Soc Indic Res. 2017;133:373–93.

Ware JrJ. SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000;25:3130–9.

Van Leeuwen C, Van Der Woude L, Post M. Validity of the mental health subscale of the SF-36 in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:707–10.

The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1569–85.

Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M. editors. Measures in health psychology: a user’s portfolio Causal and control beliefs. 1. Windsor: NFER-NELSON; 1995, pp 35–37.

Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. 1978;19:2–21.

Bath P, Deeg D, Poppelaars J. The harmonisation of longitudinal data: a case study using data from cohort studies in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Ageing Soc. 2010;30:1419–37.

StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 16. College Station: StataCorp LLC; 2019.

Cohen J, editor. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Hillsdale; 1988.

Hoeymans N, Garssen AA, Westert GP, Verhaak PF. Measuring mental health of the Dutch population: a comparison of the GHQ-12 and the MHI-5. Health Qual Life Out. 2004;2:23–29.

Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol Bull. 1988;103:193–210.

Müller R, Rauch A, Cieza A, Geyh S. Social support and functioning in a patient with spinal cord injury: the role of social skills. Int J Rehabil Res. 2013;36:236–45.

Postmes T, Haslam S, Jans L. A single-item measure of social identification: reliability, validity, and utility. Brit J Soc Psychol. 2013;52:597–617.

Whisman MA. The association between depression and marital dissatisfaction. In: Beach SRH, editor. Marital and family processes in depression: a scientific foundation for clinical practice. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2001, pp 3–24.

Acknowledgements

We thank the SwiSCI Steering Committee with its members Xavier Jordan, Fabienne Reynard (Clinique Romande de Réadaptation, Sion); Michael Baumberger, Hans Peter Gmünder (Swiss Paraplegic Center, Nottwil); Armin Curt, Martin Schubert (University Clinic Balgrist, Zürich); Margret Hund-Georgiadis, Kerstin Hug (REHAB Basel, Basel); Laurent Prince (Swiss Paraplegic Association, Nottwil); Heidi Hanselmann (Swiss Paraplegic Foundation, Nottwil); Daniel Joggi (Representative of persons with SCI); Nadja Münzel (Parahelp, Nottwil); Mirjam Brach, Gerold Stucki (Swiss Paraplegic Research, Nottwil); Armin Gemperli (SwiSCI Coordination Group at Swiss Paraplegic Research, Nottwil).

Funding

SwiSCI is hosted and funded by Swiss Paraplegic Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VC contributed to the study protocol design, the preparation, harmonization, and analysis of the data, the interpretation of the results, and the drafting of the manuscript. SK contributed to the study protocol design, the harmonization discussion, the analysis of the data, the interpretation of the results, and gave feedback on the manuscript. CP contributed to the study protocol design, the harmonization discussion, the interpretation of the results, and gave feedback on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was granted by the Ethikkommision Nordwest-und Zentralschweiz (EKNZ, Project-ID: 11042 PB_2016-02608, approved Dec 2016). We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carrard, V., Kunz, S. & Peter, C. Mental health, quality of life, self-efficacy, and social support of individuals living with spinal cord injury in Switzerland compared to that of the general population. Spinal Cord 59, 398–409 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00582-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00582-5

This article is cited by

-

Reciprocal association between pain and quality of life after newly acquired spinal cord injury

Quality of Life Research (2024)

-

Australian arm of the International Spinal Cord Injury (Aus-InSCI) Community Survey: 3. Drivers of quality of life in people with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Predictors of quality of life of individuals living in Brazil with spinal cord injury/disease

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Pharmacologic therapies of pain in patients with spinal cord injury: a systematic review

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2022)

-

Pathways to loneliness: a mediation analysis investigating the social gradient of loneliness in persons with disabilities in Switzerland

International Journal for Equity in Health (2021)