Abstract

Study design

Cross-sectional reliability and validation study.

Objective

To translate and assess the psychometric properties of the Thai version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III—Self Report (TH-SCIM-SR) in Thai spinal cord injury (SCI) patients.

Setting

Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University.

Methods

A cross-cultural forward and backward translation of the original Spinal Cord Independence Measure III—Self Report (SCIM-SR) was performed at the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand, to create the TH-SCIM-SR. The inclusion criteria were Thai patients with SCI duration of ≥3 months. Patients were evaluated by a team of healthcare professionals using the Thai version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure Version III (TH-SCIM III). Study patients subsequently completed the TH-SCIM-SR two times with a 3-day interval between evaluations. Cronbach’s Alpha, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were used to examine internal consistency, concurrent validity, and reliability, respectively. Bland–Altman plot was used to compare scoring results between the TH-SCIM III and the TH-SCIM-SR.

Results

Thirty-two patients were included. Cronbach’s alpha of total score, self-care subscale, respiration/sphincter management, and mobility subscale were 0.91, 0.94, 0.75, and 0.90, respectively. The reliability analysis showed good reliability. The test–retest ICC of total score, self-care subscale, respiration/sphincter management, and mobility subscale were 0.95, 0.95, 0.78, and 0.96, respectively. Regarding construct validity, the subscales of TH-SCIM-SR demonstrated a strong correlation with those of the TH-SCIM III (0.85–0.96).

Conclusions

TH-SCIM-SR showed good reliability and validity for assessing functional independence in Thai patients with SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a relatively low incidence but very high-cost health condition [1] that often results in disability, hindered activities of daily living (ADLs) and decreased independence [2]. Many questionnaires and scales have been designed to assess functional status and outcome of treatment, including Spinal Cord Independence Measure Version III (SCIM III) [3], Functional Independence Measure [4] score, and Spinal Cord Injury Functional Ambulation Profile [5]. These can be used to guide clinicians in determining treatment goals and objectives for patients with SCI.

The SCIM III has 19 questions that are divided into three domains, including self-care (scored from 0 to 20), mobility (scored from 0 to 40), and respiration/sphincter management (scored from 0 to 40). Questionnaire scoring ranges from 0 (the lowest level of independence) to 100 (the highest level of independence). The SCIM III assesses the daily activities of patients with SCI; however, evaluation using the SCIM III requires observation by healthcare personnel. These evaluations often require inpatient evaluation, and they are generally time-consuming. Fekete et al. developed the self-report version of the SCIM III (SCIM-SR) with a total score that ranges from 0 to 100. This questionnaire comprises 19 ADL-related questions that are classified into the same three subscales used in the SCIM III [6]. Previous studies found a strong correlation between the SCIM-SR and the SCIM III, and the reliability of the SCIM-SR was high [6,7,8].

The SCIM III was translated into Thai language (TH-SCIM III) by Wannapakhe et al. in 2016 [9] (see Supplementary Appendix 1). However, even though the SCIM-SR was recently translated into English, Spanish [7], and Italian [8], no Thai translation of the SCIM-SR has been reported. Accordingly, this study aimed to translate and then test the validity and reliability of the Thai version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III—Self-Report (TH-SCIM-SR) in Thai patients with SCI. (see Supplementary Appendix 2).

Materials and methods

Participants

Thai patients with SCI (aged 20–80 years) who were treated at the outpatient department of the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand were enrolled from 2015 to 2019. The inclusion criteria were Thai patients (those who have Thai nationality and living in Thailand) with SCI (traumatic or nontraumatic cause) with an SCI duration longer than 3 months. (The greatest rate of motor recovery occurring within 3 months.) [10] The exclusion criteria were severe health conditions, uncontrolled psychiatric disease, or cognitive impairment. The protocol for this study was approved by the Siriraj Institutional Review Board (SIRB) (COA no. 234/2557[EC3]).

Procedure

After providing written informed consent to participate, enrolled patients completed the TH-SCIM-SR. If a patient had limited hand function, the patient’s caregiver (his/her relative who stayed with patient) could help complete the questionnaire. However, to prevent answer interference, the caregiver was not permitted to explain or discuss the questionnaire, which could influence the patient’s understanding of the question and the resulting answer. A study investigator (physiotherapist or spine surgeon) then recorded demographic and clinical data (i.e., age, gender, comorbidities, etiology, level of lesion, and American Spinal Injury Association [ASIA] Impairment Scale grade) obtained from the patient interview and a review of medical records, and completed the Thai version of the SCIM III (TH-SCIM III) [9] by observing all SCIM III-evaluated activities during the same evaluation day. To evaluate test–retest reliability, patients were given a second copy of the TH-SCIM-SR assessment, and they were instructed to complete the second TH-SCIM-SR assessment 3 days after they completed the first TH-SCIM-SR assessment at their home. Patients were asked to then send back the second TH-SCIM-SR to the research team by mail. If the second assessment was not received, patients were contacted by a research assistant, and they were interviewed by telephone within 7 days after the first visit.

The SCIM III questionnaire

The SCIM III had been reported good validity and reliability in previous studies. [11] The SCIM III was translated to many languages, including Hindi [12], Spanish, Korean [13], Persian [14], Turkish [15, 16], Portuguese [17], Italian [18], and Thai [9]. The Thai version of the SCIM III (TH-SCIM III) was developed by Wannapakhe et al. in 2016 [9]. Permission was graciously given by Dr. Jirabhorn Wannapakhe for us to use the TH-SCIM III in this study.

The SCIM-SR was reported in 2013 by Fekete et al. [6], and it contains 19 questions that are divided into three domains similar to the SCIM III. The SCIM-SR was adapted by using personal pronouns, decomposing complex topics, and avoiding or rewording technical terms. Scoring of the SCIM-SR also ranges from 0 (lower independence) to 100 (greater independence). The SCIM-SR was translated to German, English, Italian, and Spanish, and previous studies reported good reliability and validity of the translated version of the SCIM-SR with the translated version of the SCIM III. Permission was generously granted by Dr. Christine Fekete to translate the SCIM-SF into Thai language.

Translation

The translation and cross-cultural adaptation procedures were performed according to the guidelines proposed by Beaton et al. [19]. The English language version of the SCIM-SR was independently translated and cross-culturally adapted to Thai language by a bilingual Thai spine surgeon and by nonmedical professional translators. Those two versions were merged and analyzed in detail until consensus was reached among the study investigators. Backward translation was then performed by a bilingual professional English language translator who speaks Thai as a second language, and he was blinded to the original English language version. The back-translated English language version was then compared with the original English language version. A reconciliation meeting was conducted among the study investigators to obtain a pre-final consensus version of the TH-SCIM-SR. Ten healthy volunteers completed the pre-final version of the questionnaire to identify any translation-related misunderstandings or confusion. After the pilot study, the final version of TH-SCIM-SR was administrated to enrolled patients.

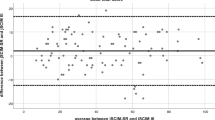

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

From a study by Bonett et al. [19], using a planning estimate of \(\mathop{\theta}\limits^{\sim}\) 0.9, and the desired width of 0.18, a minimum sample size of 32 patients was calculated. Demographic and clinical data were analyzed descriptively, and those results are reported as frequency and percentage for categorical data and as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range for continuous data, depending on the distribution of data. Descriptive statistics were also reported for the total and subscale scores of the TH-SCIM III and TH-SCIM-SR. Reliability assessment was determined by internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha and test–retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.7 or higher was considered acceptable for internal consistency, but scores above 0.8 and 0.9 were deemed to be good and excellent, respectively. Concurrent validity was assessed by comparing the TH-SCIM-SR with the results of the TH-SCIM III using Pearson’s correlation analysis. The correlation coefficient was interpreted as follows: ±0.1 was considered weak, ±0.3 was considered moderate, and ±0.5 was considered to be a strong correlation. The Bland–Altman method was used to calculate the mean difference and limits of agreement (LOA) to describe the differences between TH-SCIM III and TH-SCIM-SR total and subscale scores. Bland–Altman plots were used to illustrate the difference in TH-SCIM-SR and TH-SCIM III scores against the mean score of both measurements for each participant. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc v.17.6 and SPSS V.18.

Results

Thirty-two patients with an average age of 44.97 ± 20.31 years were enrolled. Most patients were male (28/32, 87.0%), and ASIA grade A (19/32, 61.0%). C5–C8 were the most common neurological level of injury (47.0%). Demographic and clinical data of study patients are shown in Table 1. The total and subscale scores of the TH-SCIM III and the TH-SCIM-SR, including mean, median, minimum, maximum, floor effect, and ceiling effect, are shown in Table 2.

The Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable for the total score and for all subscale scores. The Cronbach’s alpha values for total score, self-care, respiration and sphincter management, and mobility were 0.91, 0.94, 0.75, and 0.90, respectively. The ICC of test–retest reliability for total score, self-care, respiration and sphincter management, and mobility were 0.9,5 0.95, 0.78, and 0.96, respectively. The respiration and sphincter management subscale had the lowest ICC (ICC: 0.788, 95% CI: 0.607–0.891). All ICC results are shown in Table 3.

Concurrent validity was assessed by comparing the TH-SCIM-SR with the TH-SCIM III, and that analysis demonstrated a strong correlation for the total score and all subscale scores (Pearson’s correlation coefficient range: 0.859–0.960). The most well-correlated domains were self-care and mobility. Differences in the mean data by Bland–Altman and concurrent validity analysis are shown in Table 3. In addition, most of the inter-item correlations within and between subscales showed good correlation, especially between self-care and respiration and sphincter management (0.81). The inter-item correlation matrix is shown in the appendix. Agreement between tests for the total and subscale scores, as analyzed by the Bland–Altman method is shown in Fig. 1. The mean differences ranged from −0.063 to 1.56, which confirms the good agreement between the TH-SCIM-SR and the TH-SCIM III. The LOA ranged ~±13 for the total score, ±5 for the self-care subscale, ±7 for the respiration and sphincter management subscale, and ±6 for the mobility subscale. The relative difference ranged from 0.16% to 3.92%, and the Bland–Altman plots showing agreement between the TH-SCIM III and the TH-SCIM-SR showed a few outliers for each scale (Fig. 1).

Discussion

In the present study, the SCIM-SR was translated into the Thai language to create the Thai version of the SCIM-SR or TH-SCIM-SR. Similar to previous studies [6,7,8], our results showed the TH-SCIM-SR to have good reliability and validity compared to the TH-SCIM III for evaluation functional independence in SCI. The average scores for the total score and each subscale score were similar between the TH-SCIM-SR and the TH-SCIM III.

We also found that the TH-SCIM-SR has very good to excellent reliability (ICC range: 0.78–0.96), which is similar to previous study (ICC range: 0.80–0.93). Interestingly, the respiration and sphincter management subscale had the lowest ICC in all previous studies (ICC range: 0.78–0.80). We also found the respiration and sphincter subscale ICC (0.788) to be lower than the total score and the scores of the other two subscales.

In the present study, the strongest correlation with the TH-SCIM III was for the self-care and mobility subscales. Consistent with previous studies, the respiration and sphincter management subscale had the lowest Pearson’s correlation coefficient. In addition, with the exception of the respiration and sphincter management subscale, the present study was the only study that reported excellent internal consistency (>0.9).

Regarding mean difference according to Bland–Altman analysis, we found only small differences (range: 0.06–1.56) between the TH-SCIM III and the TH-SCIM-SR, which suggests that patients rated their function nearly the same as how medical professionals rated their function. In contrast, Fekete et al. [6] found that patients rated their function higher than professionals, in particular for mobility. Data compared between previous studies and the present study are shown in Table 4.

Limitations

Even though our sample size satisfied the minimum requirement according to our sample size calculation, the size of our sample may have been too small to give our study the statistical power needed to identify all significant differences and associations in subscale analysis. The second assessment by telephone interview is also the limitation of our study due to the different mode of data collection, Having acknowledged that potential limitation, our findings are consistent with those reported from other studies that translated the SCIM-SR into their native language.

Conclusion

The TH-SCIM-SR was found to have good reliability and validity for assessing independence in Thai patients with SCI. These can be used to helps clinicians and patients with SCI in determining treatment goals and objectives of rehabilitation program, and also enrich the patient’s satisfaction of treatment and rehabilitation

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bickenbach J, Officer A, Shakespeare T, von Groote P, World Health Organization, The International Spinal Cord S. International perspectives on spinal cord injury/edited by Jerome Bickenbach… [et al.]. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2013.

Karatas G, Metli N, Yalcin E, Gunduz R, Karatas F, Akyuz M. The effects of the level of spinal cord injury on life satisfaction and disability. Ideggyogy Sz. 2020;73:27–34.

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Tesio L, Biering-Sorensen F, Weeks C, Laramee MT, et al. A multicenter international study on the spinal cord independence measure, version III: rasch psychometric validation. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:275–91.

Keith RA, Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Sherwin FS. The Functional Independence Measure: a new tool for rehabilitation. Adv Clin Rehabil. 1987;1:6–18.

Musselman K, Brunton K, Lam T, Yang J. Spinal cord injury functional ambulation profile: a new measure of walking ability. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:285–93.

Fekete C, Eriks-Hoogland I, Baumberger M, Catz A, Itzkovich M, Luthi H, et al. Development and validation of a self-report version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III). Spinal Cord. 2013;51:40–7.

Aguilar-Rodriguez M, Pena-Paches L, Grao-Castellote C, Torralba-Collados F, Hervas-Marin D, Giner-Pascual M. Adaptation and validation of the Spanish self-report version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III). Spinal Cord. 2015;53:451–4.

Bonavita J, Torre M, China S, Bressi F, Bonatti E, Capirossi R, et al. Validation of the Italian version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III) Self-Report. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:553–60.

Wannapakhe J, Saensook W, Keawjoho C, Amatachaya S. Reliability and discriminative ability of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III (Thai version). Spinal Cord. 2016;54:213–20.

Kirshblum S, Millis S, McKinley W, Tulsky D. Late neurologic recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1811–7.

Itzkovich M, Shefler H, Front L, Gur-Pollack R, Elkayam K, Bluvshtein V, et al. SCIM III (Spinal Cord Independence Measure version III): reliability of assessment by interview and comparison with assessment by observation. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:46–51.

Kumar S, Khushboo, Panwar P, Garg S, Kalra S, Yadav J. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of Spinal Cord Independence Measure version III in Hindi Language. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2020;23:98–102.

Cho DY, Shin HI, Kim HR, Lee BS, Kim GR, Leigh JH, et al. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99:305–9.

Saberi H, Vosoughi F, Derakhshanrad N, Yekaninejad M, Khan ZH, Kohan AH, et al. Development of persian version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III assessed by interview: a psychometric study. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:980–6.

Kesiktas N, Paker N, Bugdayci D, Sencan S, Karan A, Muslumanoglu L. Turkish adaptation of spinal cord independence measure–version III. Int J Rehabil Res. 2012;35:88–91.

Unalan H, Misirlioglu TO, Erhan B, Akyuz M, Gunduz B, Irgi E, et al. Validity and reliability study of the Turkish version of spinal cord independence measure-III. Spinal Cord. 2015;53:455–60.

Riberto M, Tavares DA, Rimoli JR, Castineira CP, Dias RV, Franzoi AC, et al. Validation of the Brazilian version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72:439–44.

Invernizzi M, Carda S, Milani P, Mattana F, Fletzer D, Iolascon G, et al. Development and validation of the Italian version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:1194–203.

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients that joined this study, Dr. Christine Fekete, for granting us permission to translate the SCIM-SR; and Dr. Jirabhorn Wannapakhe for permission to use the TH-SCIM III. The authors also wish to thank Miss Nhathita Panatreswas for statistical analysis and for assisting with the journal submission process.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University (grant no. (IO)R015932036).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SW and PL designed the research questions. NT and PK collected and analyzed the data, PL and BS drafted the manuscript. BS and SW wrote the final version of the manuscript. SC and CC designed the research questions and commented on the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand. The study number is 234/2557(EC3). The authors certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during all courses of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilartratsami, S., Luksanapruksa, P., Santipas, B. et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric testing of the Thai version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III—Self Report. Spinal Cord 59, 291–297 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00556-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00556-7

This article is cited by

-

Validation of the Thai version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure Self-Report (SCIM-SR-Thai)

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Adaptation and validation of the Japanese version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III) self-report

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

Translation and validation of the Chinese version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III) Self-Report

Spinal Cord (2021)