Abstract

Introduction

Neurogenic bladder following acute spinal cord injury (SCI) increases urinary tract infection (UTI) risk and affects quality of life and health system costs.

Objectives

This study aimed to identify, describe and evaluate quality of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for managing neurogenic bladder following SCI.

Methods

A comprehensive search covered six electronic databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Health Systems Evidence, Cochrane, CINAHL, Epistomonikos) and 12 CPG portals. Inclusion criteria were English language CPG; includes recommendations for managing neurogenic bladder in adults; all phases of care; published 2011 onwards in peer-reviewed journal/CPG portal. For eligible CPGs, key characteristics including years covered by CPG searching and number of neurogenic bladder recommendations were extracted. Quality appraisal used the AGREE II instrument. Appraiser agreement was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient.

Results

Searching yielded 4028 citations and eight relevant CPGs. Collectively the CPGs contained 304 recommendations. Over half (160) pertained to assessment, surgery or education. Most surgery recommendations were from older CPGs; more recent CPGs emphasised conservative therapy. Methodological quality across CPGs was good in the domains of ‘clarity of presentation’ (84% mean domain score), ‘scope and purpose’ (72%) and ‘editorial independence’ (68%). There were shortcomings in the domains of ‘rigor of development’ (52%) ‘stakeholder involvement’ (42%) and ‘applicability’ (33%).

Conclusion

CPGs for the management of neurogenic bladder following SCI are generally robust in stating their scope and clearly presenting recommendations. Only three CPGs attained domain scores over 70% pertaining to methodological rigor. Future CPGs should also focus on providing implementation / audit resources and incorporating patient perspectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Disturbance to the nerves supplying the urinary bladder, known as neurogenic bladder, is common following acute spinal cord injury (SCI) [1, 2]. Neurogenic bladder in adults is defined as “abnormal or difficult function of the bladder, urethra (and/or prostate in men) in mature individuals in the context of clinically confirmed relevant neurologic disorder.” [3] Neurogenic bladder negatively impacts functional recovery, health-related quality of life, length of stay, and health care costs due to the loss of voluntary bladder control and increased risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) [4]. For these reasons, urological management is a care priority for both inpatient and community-based persons with SCI [5]. Urological management includes a broad range of interventions including catheterisation approaches, for example indwelling, intermittent, and suprapubic; [6] assisted bladder emptying; electrical stimulation; pharmacological agents and surgery [7, 8].

Clinical practice is optimised when informed by the best available evidence [9]. Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) are defined as “systematically developed statements to assist practitioners’ and patients’ decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances” (Field and Lohr 1990) [10]. Because they identify the nature, volume, and quality of research evidence supporting clinical recommendations and connect this information with clinicians at the point of care [11], CPGs can improve decision-making and, ultimately, clinical outcomes [12]. CPGs can also play a role in improving consistency of care, in providing patients and other stakeholders with information regarding the treatment they should be receiving, and in influencing health policy to enhance treatment efficiency and patient access to services [11].

Access to up-to-date, high-quality CPGs is therefore important for both clinicians and persons with SCI, particularly given the breadth of approaches to neurogenic bladder management following SCI. Evaluating the methodological quality of CPGs aids in the interpretation of their recommendations and identifies future priorities for guideline development. The aim of the present study was to identify and evaluate the methodological quality of published CPGs for neurogenic bladder management following SCI.

Methods

Guideline search and selection

To identify relevant published guidelines, six electronic health databases and 12 web-based CPG portals were searched. The databases were PubMed (US National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information, NCBI), Web of Science (Institute for Scientific Information, ISI), Health Systems Evidence (McMaster University, Canada), The Cochrane Database (Wiley), CINAHL (EBSCOhost) and Epistomonikos (Epistomonikos Foundation, Chile). Key search terms included ‘spinal cord injury’, ‘neurogenic bladder’, ‘neuropathic bladder’ and ‘bladder management.’

All searches were conducted on 9 November 2015 and updated on 19 February 2018. Appendix 1 lists all websites searched. Appendix 2 contains an example of the search strategy used for health databases (PubMed). Titles, abstracts and full-text publications were evaluated for inclusion using the following criteria:

-

Patient group: adults with neurogenic bladder dysfunction arising from SCI (guidelines could also include reference to other causes of neurogenic bladder e.g. multiple sclerosis, stroke)

-

Study type: Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG), defined as above [10]. The guideline had to include specific practice recommendations and be evidence based, as reflected by the following items on the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) instrument: [13]

-

‘Systematic methods were used to search for evidence’

-

‘There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence’

-

-

Scope: the scope of the CPG was required to specifically focus on, or incorporate, recommendations for management of the Neurogenic Bladder following SCI. All bladder management techniques and all outcomes measures were eligible.

-

Phase of care: all relevant phases of care including community-based care.

-

Date Range: searching was conducted for CPGs published from 2011 onwards in order to capture the most recent evidence (date range unlimited for searches within each guideline).

-

Language: English.

-

Accessibility: published in peer-reviewed journals, or via CPG portals.

Two researchers (PB and DG) evaluated titles and abstracts from database searches to identify potentially relevant publications for full-text review and two researchers reviewed websites to identify publications for full-text review (PB and BW). Full-text publications from both databases and websites were reviewed by at least three researchers (drawn from PB, DG, BW and SG) with disagreements or uncertainties regarding inclusion resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each CPG by PB: country of origin, year of publication, years covered by literature searching, number of neurogenic bladder care CPG recommendations in total, and number of CPG recommendations pertaining to specific neurogenic bladder management techniques. For the purpose of calculating the number of CPG recommendations, a CPG recommendation was defined with reference to the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) instrument criteria for evaluating clarity of presentation (Item 17):

-

“description of recommendations in a summarized box, typed in bold, underlined, or presented as flow charts or algorithms

-

specific recommendations are grouped together in one section” [page 31] [14]

CPGs were categorized under their primary headings as used in the CPGs.

Quality appraisal

Eligible CPGs were evaluated using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) instrument [13]. The AGREE II comprises 23 quality appraisal items across six domains: (1) scope and purpose, (2) stakeholder involvement, (3) rigor of development, (4) clarity of presentation, (5) applicability and (6) editorial independence. A further item rates the overall quality of the guideline. Each item is scored on a scale from 1 (absence of information or concept very poorly reported) to 7 (exceptional quality of reporting, all criteria for item met) [13]. The AGREE II has established construct validity [15] and inter-rater reliability [16], and AGREE II quality ratings have been shown to be significant predictors of guideline endorsement and overall intention to use a guideline [16].

In accordance with the AGREE II instrument protocol, each CPG was independently evaluated by at least two raters drawn from the entire research team (PB, BW, SG, DG, EG and MB). At least four raters evaluated the CPGs initially identified; for the update search two raters were used. For each guideline:

-

Standardized Domain Scores for each of the six domains were calculated based on the AGREE formula: (Obtained Score from all raters—Minimum Possible Score from all raters)/(Maximum Possible Score from all raters—Minimum Possible Score from all raters).

-

Individual scores for the 23 AGREE items and the summary overall quality score were calculated by totaling the scores given by all raters and dividing this by the maximum possible score for each item.

-

Agreement between raters on evaluation of each AGREE II criteria within each eligible CPG was assessed using an intra-class correlation coefficient (2-way random model, IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25).

The AGREE manual does not set a benchmark of minimum domain scores representing ‘high’ or ‘poor’ quality; users are advised to set their own criteria based on the context of their appraisal project [14]. In this project, scores are reported against a benchmark of 50%, where scores higher than 50% represent higher quality and scores below 50% represent lower quality.

Results

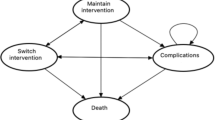

Figure 1 presents an overview of results of searching, screening and full-text review based on the PRISMA systematic review reporting guidelines [17]. Searching yielded 3795 citations after removal of duplicates, of which 55 full-text documents were reviewed. Eight CPGs met all inclusion criteria. These were from the following organisations:

-

German Society of Urology (DGU) [18]

-

Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) [19]

-

Neurologic Incontinence Committee (NIC) [20]

-

European Association of Urology (EAU) [8]

-

National Clinical Guideline Centre (NCGC) [21]

-

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) [22]

-

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [23]

-

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine (CSCM) [24]

Table 1 presents an overview of included CPGs. Only two CPGs encompassed literature up to and including the last five years (EAU, SUFU). The included CPGs collectively contained 304 recommendations pertaining to management of the neurogenic bladder. Over half of these pertained to surgery (67 recommendations) assessment (61), or education/support (32). Other categories with 20 or more recommendations were pharmacological agents (25), urinary tract infection (including prevention; 20) and intermittent catheterisation (22—a further 19 recommendations for indwelling catheterisation).

Quality appraisal

Table 2 presents scores by each of the six AGREE domains for each CPG. Table 3 presents the scores by individual AGREE items for each CPG, revealing specific areas of higher and lower performance. Guidelines with domain scores over 50% in all six domains were those of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (range 65–92%) and the National Clinical Guideline Centre (range 62–94%), as reflected by their overall quality scores which were both over 80% (Table 3).

Across all guidelines, methodological quality was highest in the domains of (a) ‘clarity of presentation’ (domain 4, mean score 84%; mean scores across three items 86–90%), (b) ‘scope and purpose’ (domain 1, 72%, means 69–85%, three items) and (c) ‘editorial independence’ (domain 6, 68%, means 69–75%, two items). The domain score was reasonable in the area of ‘rigor of development’ (domain 3, 52%, means 39–77%, eight items). CPGs generally performed well in the areas of linking recommendations to evidence (mean 77%), considering benefits, side effects and risks (75%), using systematic search methods (69%) and describing inclusion criteria (61%).

Appraisers identified the following areas for improvement: (a) describing the strengths and weaknesses of the literature (55%), (b) describing how recommendations were formed (58%), (c) having the CPG externally reviewed (39%) and (d) outlining CPG updating procedures (41%). These contributed to the relatively lower overall domain score.

Domain score were lowest in ‘stakeholder involvement’ (domain 2, 42%, means 31–65, three items) and ‘applicability’ (domain 5, 33%, means 37–48%, four items). The low score for stakeholder involvement was due predominantly to failure to seek the views of the target population for the CPG—an area in which only two CPGs performed satisfactorily (NCGC and SIGN). Performance in all four items within the ‘applicability’ domain was poor, with no individual item generating a mean score above 50% across all CPGs and only two CPGs satisfactorily addressing the majority of items in this domain (NCGC and SIGN).

Appraiser agreement

Table 4 presents Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) for agreement among raters across the eight CPGs evaluated. Agreement between raters was very good overall, with very high agreement (ICC ≥ 0.90) for five CPGs, high agreement ( ≥ 0.80) for one CPGs and ICCs of 0.791 and 0.614 for the remaining two CPGs.

Discussion

This project is the first known comprehensive search and evaluation of the methodological quality of CPGs addressing management of the neurogenic bladder following SCI. Systematic evaluation of CPG content enables an overview of all available CPGs addressing a clinical care area that can identify practice patterns and trends. This gives practicing clinicians an entry point to available evidence-based approaches to care. Appraisal of methodological quality of CPGs can identify both primary research opportunities (where there is uncertainty over treatment effectiveness owing to a lack of high-quality studies) and areas of focus for CPG developers. The strengths of this project included the use of AGREE II, a validated critical appraisal instrument for CPGs, and very good agreement among a relatively large pool of raters, which enhances confidence in the AGREE II appraisal findings.

While some critical appraisal tools employ weighting of scores to reflect their relative importance [25], all appraisal items are given equal weight in the AGREE II instrument. It could therefore be argued that some items considered of particular importance in guideline development—for example systematic searching for evidence—are not adequately weighted in the overall scores. This aspect of the AGREE II appraisal should be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings of this study. Another limitation of this review is the focus on English-only CPGs, as it was not feasible to translate non-English CPGs. It is possible that inclusion of non-English CPGs could alter the findings of this review in relation to both CPG quality and CPG content. Finally, the scope and focus of the included CPGs varied, with some covering all aspects of neurogenic bladder management and others focusing on specific areas of care. Whilst not a limitation of the CPG review process, clinicians should bear in mind that due to this variation there are limited recommendations in some areas of neurogenic bladder management.

The eight CPGs included in this study collectively contained 304 recommendations, with the highest volume of recommendations in the areas of surgery (n = 67), assessment (n = 61), education/training (n = 32) and intermittent catheterisation (n = 22). Although this project focused on CPG quality rather than content, it is interesting to observe the relatively high volume of surgical recommendations, which encompass multiple types of surgery including stents, sphincterotomy, urinary diversion and bladder augmentation. It should be noted that 23 of these recommendations were in the oldest of the included CPGs, published in 2006 [24]. More recent CPGs, for example that of the European Association of Urology [8], conclude that numerous conservative and non-invasive options should be considered before surgery. This signals a shift in management over this decade away from surgical to conservative treatment. For example, intermittent catheterisation has recently been described as “the treatment of choice for patients with difficulty emptying their bladder due to neurogenic and non-neurogenic causes, due to its wide availability and minimally invasive nature” (p. 931) [26]. This trend is further underlined by the relatively high volume of education/training recommendations (32) amongst the included CPGs. Similarly, trends can be identified in pharmacological management, with the oldest of the CPGs focusing on alpha-blockers [24] and more recent guidelines covering antimuscarinic [20] and antibiotic prophylaxis agents [19].

The findings of AGREE II appraisals have important implications for CPG development in this field. The mean domain score of 52% for ‘rigor of development’ is modest. Exploration of the individual items within this domain indicates the included CPGs used robust evidence search, selection and appraisal techniques; linked recommendations to supporting evidence, and considered risks versus benefits in formulating recommendations. High performance in these aspects of CPG development enables end-users to have confidence that sound processes were used to identify evidence and link this evidence to the recommendations. Future guidelines in this area, in addition to considering these aspects, should describe the strengths and weaknesses of the literature, be explicit about how recommendations were formed, have the CPG externally reviewed and outline CPG updating procedures.

Many factors influence clinicians in determining the most useful CPGs for their practice. According to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) these include specifics of the intervention (for example strength of evidence, adaptability, cost, complexity); patient needs and peer influence; organisational characteristics including implementation readiness; and individual clinician beliefs and attributes [27]. Information and tools to implement guideline recommendations into practice are therefore a critical component of CPGs. Lack of such information and tools was a clear shortcoming of the included CPGs, with a mean domain score for ‘applicability’ of only 33%. Deficiencies in implementation guidance and audit practice have been a consistent finding across multiple CPG reviews, for example in the area of traumatic brain injury [28,29,30]. A lack of tools to implement and monitor CPGs or CPG recommendations risks wasting the considerable resources invested in creating CPGs. One way to address this limitation would be to ensure that researchers with expertise in implementation science are involved in guideline development so that the full potential of CPGs to benefit patients and the health system can be realised and measured.

‘Stakeholder involvement’ was another area in which shortcomings were identified across the guidelines appraised, especially with regards to seeking views of patients and unpaid carers of people with SCI. Patient preferences, along with research evidence and clinical experience, are foundations of evidence-based practice [31]. In recent years there has been increasing emphasis on ensuring that the patient voice is an integral part of the medical research agenda, for example through the establishment of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) [32]. In this context, CPG developers should redouble their efforts to ensure that views and preferences of the target population are incorporated into CPG development.

Conclusion

This paper provides an assessment of the content and quality of CPGs focused on the management of neurogenic bladder for persons with SCI. Eight CPGs were identified. Results of quality appraisal indicated that existing guidelines have generally employed systematic methods of searching for, selecting and appraising research evidence underpinning clinical practice recommendations within the guidelines; articulated their overall objectives, scope and audience well; and produced unambiguous, clearly identifiable recommendations. The assessment has also highlighted the need for future CPGS to in this healthcare area to focus on co-production with involvement from all relevant stakeholders, and provide CPG implementation and adoption resources.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Anderson CE, Chamberlain JD, Jordan X, Kessler TM, Luca E, Möhr S, et al. Bladder emptying method is the primary determinant of urinary tract infections in patients with spinal cord injury: results from a prospective rehabilitation cohort study. BJU Int. 2019;123:342–52.

Welk B, Schneider MP, Thavaseelan J, Traini LR, Curt A, Kessler TM. Early urological care of patients with spinal cord injury. World J Urol. 2018;36:1537–44.

Gajewski JB, Schurch B, Hamid R, Averbeck M, Sakakibara R, Agrò EF, et al. An International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (ANLUTD). Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37:1152–61. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/nau.23397

Goetz LL, Cardenas DD, Kennelly M, Lee BSB, Linsenmeyer T, Moser C, et al. International spinal cord injury urinary tract infection basic data set. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:700–4. http://www.nature.com/sc/journal/v51/n9/pdf/sc201372a.pdf

Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1371–83. http://www.liebertonline.com/doi/abs/10.1089/neu.2004.21.1371

Adams J, Watts R, Yearwood M, Watts A, Hartshorn C, Simpson S, et al. Strategies to promote intermittent self‐catheterisation in adults with neurogenic bladders: a comprehensive systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2011;9:1392–446.

Blok B, Pannek Castro-Diaz JD, del Popolo G, Groen J, Hamid R, Karsenty G, et al. EAU guidelines on neuro-urology. Eur Urol. 2015;69:324–33.

Groen J, Pannek J, Castro Diaz D, Del Popolo G, Gross T, Hamid R, et al. Summary of European Association of Urology (EAU) Guidelines on Neuro-Urology. Eur Urol. 2016;69:324–33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26304502

Glasziou P, Ogrinc G, Goodman S. Can evidence-based medicine and clinical quality improvement learn from each other? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(Suppl 1):i13–7. http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.046524

Field MJ, Lohr KN. Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 1990.

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:527–30.

Keris V, Lavendelis E, Macane I. Association between implementation of clinical practice guidelines and outcome for traumatic brain injury. World J Surg. 2007;31:1352–5.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1308–11. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0895435610002477

AGREE Next Steps Consortium (2017). The AGREE II Instrument [Electronic version]. Canada: The AGREE Research Trust. Retrieved April 8, 2019, from http://www.agreetrust.org.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182:E472–8. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/doi/10.1503/cmaj.091716

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 1: performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182:1045–52. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/doi/10.1503/cmaj.091714

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Böthig R, Geng V, Kurze I. Management and implementation of intermittent catheterization in neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Int J Urol Nurs. 2017;11:173–81. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/ijun.12145

Cameron AP, Campeau L, Brucker BM, Clemens JQ, Bales GT, Albo ME, et al. Best practice policy statement on urodynamic antibiotic prophylaxis in the non-index patient. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:915–26. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/nau.23253

Drake MJ, Apostolidis A, Cocci A, Emmanuel A, Gajewski JB, Harrison SCW, et al. Neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: Clinical management recommendations of the Neurologic Incontinence committee of the fifth International Consultation on Incontinence 2013. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016;35:657–65. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/nau.23027

National Clinical Guideline Centre. Urinary Incontinence in Neurological Disease: Management of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction in Neurological Disease. Clinical Guideline 148: Methods, evidence and recommendations. London: National Clinical Guideline Centre; 2012.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2012. (SIGN publication no. 88). [July 2012]. Available from http://www.sign.ac.uk

Joanna B Institute. Strategies to promote intermittent self-catheterization in adults with neurogenic bladders. Adelaide, Australia: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2011.

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care providers. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29(5):527–73. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17274492

Katrak P, Bialocerkowski AE, Massy-Westropp N, Kumar VS, Grimmer KA. A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC Med Res Method. 2004;4:22. Available from: http://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-4-22

Lamin E, Newman DK. Clean intermittent catheterization revisited. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48:931–9. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11255-016-1236-9

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Pattuwage L, Olver J, Martin C, Lai F, Piccenna L, Gruen R, et al. Management of spasticity in moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016;32:E1–E12. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27120291

Bragge P, Pattuwage L, Marshall S, Pitt V, Piccenna L, Stergiou-Kita M, et al. Quality of guidelines for cognitive rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29:277–89. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24984092

Tavender EJ, Bosch M, Green S, O’Connor D, Pitt V, Phillips K, et al. Quality and consistency of guidelines for the management of mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:880–9.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray J, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71–2. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/312/7023/71

Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA. 2012;307:1583–4.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following people who worked on related projects to this guideline review which included discussion of CPGs—James Brock, Sarah Dunlop, Louise Goodes, James Middleton, Andrew Nunn. We also acknowledge Andrew Nunn as Lead CI of the program within which this review was undertaken.

Funding

The project described in this manuscript was funded by the Victorian Transport Accident Commission (TAC) through Monash University’s Institute for Safety, Compensation and Recovery Research (ISCRR) [Project number 138, Lead CIs Nunn, Bragge]. The research funders played no role in the acquisition, analysis, interpretation or writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PB conceived the review, participated in search, screening and selection of included CPGs, undertook AGREE II appraisal of included CPGs, analysed ICCs and drafted the manuscript including preparation of tables. PB confirms that he has had full access to the data in the study and takes final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. SG, DG and BW participated in search, screening and selection of included CPGs, undertook AGREE II appraisal of included CPGs and contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript. MB and EG undertook AGREE II appraisal of included CPGs and contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bragge, P., Guy, S., Boulet, M. et al. A systematic review of the content and quality of clinical practice guidelines for management of the neurogenic bladder following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 57, 540–549 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0278-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0278-0