Abstract

Study design

Cross-sectional study.

Objectives

To provide data on depressive symptoms rates in the Greek SCI population and to investigate their association with demographic and clinical variables.

Setting

Greek territory.

Methods

One hundred and sixty-four individuals with SCI living in the community for at least 1 year after the completion of the primary inpatient rehabilitation program were included in the study. Our group of participants were enrolled from multiple rehabilitation centers throughout Greece and were evaluated for probable depression according to the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Univariable and multiple linear regression analyses were performed to assess the possible association of risk factors with the occurrence of depression. We had also examined the correlation between PHQ-9 and scales measuring social reintegration (Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique (CHART)), quality of life (World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHOQOL-BREF)), and independence (Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM)).

Results

It was found that 18.2% of the sample had probable depression. The mean (SD) PHQ-9 score was 5.7 (4.9). The multiple linear regression analysis showed that high pain scores (P = 0.001) and suffering from both nociceptive and neuropathic pain (P = 0.005) were associated with depressive mood, while pressure ulcers had a significant effect (P = 0.049) only in the univariable analysis. Participant’s PHQ-9 scores had also a negative correlation with almost all CHART, WHOQOL-BREF, and SCIM subscales’ scores.

Conclusions

This study documents relatively low rates of probable depression among individuals with SCI in Greece. Severe pain and pressure ulcers were the main identified predictors of depressive mood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a severe health condition that creates extensive changes in the lives of active members of societies all around the world. Depression is a frequent complication in this population and has been considered as the main obstacle to health-related quality of life (QoL), contributing to premature mortality. Both psychological and functional dimensions of depression are involved, by means of negative effect on the implementation of daily life activities. It also has a negative impact on the ability of someone to enter the labor market [1]. Provided that suicide is a relatively frequent cause of death among individuals with SCI [2], depression prevention, diagnosis, and treatment is crucial. According to a meta-analysis, 22.2% of SCI individuals suffer from depressive symptoms, which is substantially greater than the percentage among the general medical population, a fact which contributes to a poor QoL [3]. A 5-year longitudinal study estimated the depression rates in SCI survivors at 18–21% [4]. Similarly, among the United States of America veterans the percentage has been equivalent (22%) [5].

Several factors have been found to be associated with depressive mood. Pressure ulcers [6] and pain [7] have been identified as exacerbating agents of depressive mood among individuals with SCI. While some researchers testified that older individuals with SCI are more likely to develop depression than younger ones [8, 9], others showed that younger individuals are under higher depression risk [10]. A higher education level seems to exert a beneficial effect, preventing the appearance of a depressive disorder [1]. Life without a spouse, sedentary lifestyle [11], and excessive alcohol consumption [4] have also been correlated with an increased risk of developing depressive symptoms, while the use of the internet has positive effects, improving the emotional status of individuals with SCI [11].

Although rehabilitation approach for patients with SCI in Greece during inpatient hospitalization follows international principles, a series of unique characteristics of the Greek culture could potentially influence their psychic status. While individuals with disabilities in Greece still face stigma, discrimination, and social barriers due to social stereotypes, Public Health Care System offers an equal and free access to all users, even to those without an insurance cover [12, 13], and families present strong support among their members. The family unit is the most important foundation of the Greek society, providing emotional and economic support to the individual [13]. Our purpose is to evaluate the rates of probable depression among community-living individuals with SCI in Greece and to investigate the possible correlation between depressive mood and demographic characteristics as well as clinical parameters of the participants. Our hypothesis is that this cross-sectional study may demonstrate somehow altered percentages, regarding probable depression, in comparison with the international research in countries with different socio-cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, we expect that medical complications will have the strongest association with depressive mood.

Methods

Participants/study design

Having access to the archives of 18 public and private rehabilitation institutions all across Greece, we documented an overall summary of 1002 living individuals with SCI of any cause who had completed their inpatient rehabilitation program dating at least a year back. The data were collected during the period from January 2013 to March 2014. We excluded those aged <18 years, non-Greek speakers, and those lacking cognitive ability to complete the questionnaire. Nine hundred and twenty individuals fulfilled the inclusion criteria. We randomly recruited a 20% of the individuals with SCI from each rehabilitation institution (n1 = 184). From the selected sample, 164 accepted to participate in this survey. All institutions gave the research team full access to their medical files, so that any useful information could be retrieved. The data set used in this manuscript was also used in a previous research, already published [14]. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Informed consent brochures were administered to all subjects enrolled in the study that fully conformed with the Helsinki declaration principles and Greek Medical ethics law (Hellenic State Law 3418/2005). We therefore certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Questionnaires

Patient information was retrieved by filling in a questionnaire during a personal interview and physical examination at the time of the study by the same physiatrist. The collected information concerned demographic characteristics (age, sex, marital status, educational level, employment status, injury date, place of residence) and clinical features (severity of the injury, the degree of impairment, pain, the presence of pressure ulcers, micturition type). According to the level of the injury, participants were divided into two groups, those with paraplegia and those with tetraplegia. The ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) was used in grading the impairment’s degree [15] and the severity of pain was assessed by asking patients to rate pain between 0 and 10 on the average during the last week prior to the interview according to the Numerical Rating Scale, which is widely used in SCI patients [16]. The pain was further discriminated as neuropathic, nociceptive, or with the coexistence of both types of pain with respect to medical history and clinical signs. We excluded from the analyses regarding micturition type those with an indwelling or suprapubic catheter because of the small number of participants (n = 4 and n = 9 respectively).

This study used the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to measure the severity of depressive symptoms of the participating individuals. PHQ-9 has been identified as a useful tool to assess patients with chronic diseases and specifically people aging with SCI. It scores between 0 and 27 with higher scores being correlated with higher stages of depression [17]. It is also the only questionnaire applied in SCI population that is in conjunction with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for major depressive syndrome diagnosis [18]. More specifically, it consists of nine items that correspond to nine symptoms of depression according to DSM-IV and scores their persistence during the last 2 weeks prior to the interview from 0 to 3. Participants who score 10, or more, are characterized as individuals probably suffering from major depressive disease (MDD) [17]. The stage of the depressive mood of the sample was also classified into five categories according to PHQ-9 scoring instructions: 0–4 minimal, 5–9 mild, 10–14 moderate, 15–19 moderately severe, and 20–27 severe [17].

The PHQ-9 has been proven to have adequate sensitivity and specificity in assessing depressive disorders in people with SCI. Moreover, the reliability of the PHQ-9 has been found to be excellent (alpha = 0.87). The validity of PHQ-9 ranges according to the literature from adequate (r = −0.50 and −0.51) to excellent (r = 0.62) [19]. Furthermore, its internal consistency among SCI samples has been reported to be excellent [20].

In order to identify the possible associations between depressive disorders and social reintegration, the sample was screened with the Craig Handicap Assessment Reporting Technique (CHART), which is a reliable measure of reintegration, specifically designed for individuals with SCI [21]. The test–retest reliability of each subscale of this tool was found to be between 0.80 and 0.95 and its validity has also been certified [21]. QoL and physical independence were measured with World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) and Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM), respectively. The WHOQOL-BREF, a well-known and reliable (test–retest reliability: 0.66–0.87) QoL assessment scale, validated for the SCI population (WHOQOL-BREF validity for people with SCI: 0.52–0.77) [22], was used for the evaluation of the QoL level of the participants and the investigation for associations between probable depression and QoL. The SCIM, which was created to assess independence exclusively for individuals with SCI (inter-rater reliability: 0.91–0.99) [23], was also completed to determine any possible effects of the degree of independence on mood. The validity of SCIM is supported by its statistically significantly higher sensitivity than Functional Independence Measure to functional changes in individuals with SCI (P < 0.01) [23]. The correlations were performed with all the subscales of each of the above scales.

Statistical analyses

Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as a percentage for categorical parameters. The normality of the distribution of variables was assessed with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the normal probability plot. Univariable analysis was performed using Student’s t-test, the one-way analysis of variance model, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient to analyze the relation between the dependent variable (PHQ-9) and the categorical, quantitative parameters, respectively. Multiple linear regression analysis with the enter method, which included all variables with P < 0.2 in univariable analysis, was performed in order to find the strongest predictors of the outcome variable. All tests were two-sided and a P-value of <0.05 was used to denote statistical significance. All analyses were carried out using the statistical package SPSS vr 17.00 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Results

The demographic characteristics as well as the clinical information of the participants are presented in Table 1. The participants were mainly male (79%), pensioners or individuals receiving state benefits (61%), residents of urban areas of the Greek territory (63%), unmarried (52%), and having not entered tertiary education (78%). The mean age of the participants was 46 years (ranging from 20 to 80 years). The mean time from SCI was 15 years (ranging from 1 to 43 years). The participants were also mainly paraplegic (73.2%), with complete injury (59.1%), and without pressure ulcers (83.2%). They were mainly performing intermittent self-catheterization for bladder drainage (73.2%). The majority (62.2%) were suffering from pain of any form, while neuropathic pain presented as a dominant demonstration (53.9%). According to the Numerical Pain Scale, the average pain score of the sample was 3.9 ± 3.5.

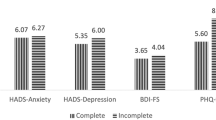

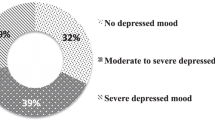

The average PHQ-9 score of the participants was 5.7 ± 4.9. The 45.7% of the sample exhibited a minimal depression (score 0–4), while 36% exhibited mild depression (score 5–9), 12.8% had moderate depression (score 10–14), 3.7% had moderately severe depression (score 15–19), and 1.8% had severe depression (score 20–27). Furthermore, a total of 18.3% of the participants can be classified as suffering from probable MDD (PHQ-9 > 10).

According to the univariable analysis [Table 2] of the data for the PHQ-9 index, it was found that depressive symptoms are more likely to occur in individuals having graduated primary (P = 0.033) or high school (P = 0.035) compared to university graduates. The same was noted for individuals with pressure ulcers in comparison with those who do not suffer from pressure ulcers (P = 0.049) and for individuals with co-existence of nociceptive and neuropathic pain compared to those without pain (P < 0.001), to those with nociceptive pain (P = 0.01), and to those with neuropathic pain (P = 0.03). Furthermore, an increased severity of pain was found to lead to a deterioration of the positive emotional status (r = 0.333, P < 0.001). Sex, marital status, place of residence, employment status, level of injury, type of micturition, AIS classification, age, and time since injury have presented no statistically significant effect on PHQ-9.

The multiple linear regression model, using PHQ-9 as the dependent variable and all demographic and clinical variables with P < 0.2 in the univariate analysis as predictors (enter method), attempted to detect the strongest predictors of the PHQ-9 index [Table 3]. There were not any violation of assumptions of the linear regression model. All variables accounted for 21.7% of the PHQ-9 score’s variance (R2 = 0.217, F(6,157) = 7.25, P < 0.001). The results showed that Pain score (beta ± SE = 0.36 ± 0.10, P = 0.001, R2 = 0.111) and Pain type (beta ± SE = 3.42 ± 1.20, P = 0.005, R2 = 0.060) were statistically significant independent predictors of PHQ-9 score. Marital status, educational level, employment status, and presence of pressure ulcers did not have statistically significant effect on the PHQ-9 score.

Simultaneously, we also examined correlations of PHQ-9 with other scales. The results are shown in Table 4. The PHQ-9 scores of the participants had a high negative correlation with all the WHOQOL-BREF subscales, low negative correlation with all the SCIM subscales except Mobility that has not gotten a statistical significant correlation, and low-to-moderate negative correlation with the CHART domains except Physical Independence that has not gotten a statistical significant correlation.

Discussion

The rate of probable depression (18%) in this sample of individuals with SCI who live in Greece is at the lower end of the range of previous results that have been reported in the international literature. Taking into consideration the meta-analysis of Williams et al., the probable depression rates found in our research are relatively low [3]. In three studies that used PHQ-9 with exactly the same cutoff criterion (PHQ-9 > 10) for probable depression, the results were 22% [24], 20% [25] and 18–21%, respectively, with 18% referring to just 1 year post-injury [4]. The slightly lower rates of depressive mood in Greece compared to other countries can be attributed to unique local cultural factors. The traditional family support network remains an important parameter that protects people with mobility difficulties from feeling lonely and/or isolated. People with SCI are also engaged in family activities, resulting in a greater inner feeling of a purpose in life, amplifying its importance. Greek culture is also characterized by close and longstanding friendships and warm human relationships. The supporting role of state and church (social policy, charity), improved accessibility to public areas during the past decades (accessible routes, curb ramps, parking and passenger loading zones, elevators, signage, restrooms' etch) and the implementation of a free access Public Health Care System for every individual with SCI are also factors contributing to emotional well-being.

Our study demonstrated that the level of depressive symptoms is not associated with the time that has passed since the injury. Other researchers also support the suggestion of no improvement of the emotional status during the time [4]. However, some researchers report that the odds of probable major depression decrease as time passes since the injury [8]. Our findings support that age has no effect on the occurrence of depressive symptoms among individuals with SCI, while other researchers propose the association of increased age with high rates of depressive mood [8, 9]. Our research, similar to other studies, found no correlation between the level of injury and probable depression [7]. However, another survey concluded that those having tetraplegia were in higher depression risk than those with paraplegia [26]. Like another study, we found no difference in probable depression between individuals with a complete and incomplete injury [7].

Our study identifies the presence of pressure ulcers as a risk factor for probable depression. Our results are consistent with a 3-year longitudinal study [6]. Pressure ulcers are reported to adversely affect self-esteem, causing low scores on mental health [12]. Participants showed no difference in their mood whether they performed intermittent catheterization or normal micturition. This may be due to the new type of catheters that are easily accepted by patients, becoming part of their routine.

In our sample, both pain intensity and coexistence of nociceptive and neuropathic pain were correlated with the appearance of depressive mood. Pain, causing confusion, fatigue, anxiety, anger, low vigor, poor self-efficacy, poor quality sleep, increased spasticity, inhibition of active sexual life, limitations on involvement in daily activities, vocational and recreational activities, and social integration, is a very common symptom among SCI survivors [27]. According to Craig et al., the experience of pain is a predictive factor of depression in a 2-year period post-injury, and its treatment should be recommended as an external intervention [7].

In our sample, the presence of a spouse did not seem to play a strong protective role regarding the occurrence of a probable depression disorder. However, previous research has proven that marriage is associated with low emotional distress [7], while there is evidence that divorced individuals with SCI are more susceptible to depressive mood than the rest of the SCI population [28]. Furthermore, we found no difference in depressive mood rates between male and female individuals, which is consistent with the results of Kalpakjian et al. [28] but is in contrast with the results of other studies that consider females as more likely to develop depression [27, 29]. Depression probability rates were almost similar for residents in urban areas, smaller towns, and rural areas, contrary to Boticello et al., who documented that people with SCI living in urban territories are at high risk to develop depressive feelings [29]. However, in Greek rural areas, the greater family relations and mutual assistance in smaller communities possibly compensate for the difficulties with accessibility in medical and social services.

In our study, there was a trend for tertiary education graduates to exhibit lower levels of depressive mood compared with those with lower educational level, partly explained by their easy access to knowledge, their ability to learn how to perform new tasks, and how to use assistive technology. Moreover, they are generally more likely to acquire a high income, which we found to be a predictive factor for low levels of depression. Similar findings, regarding the beneficial role of education, exist in the literature [9, 26]. Additionally, our findings do not support that unemployed individuals are at high depression risk, contrary to other studies that find associations between employment and emotional well-being [26, 28]. This could be a result of high rates of job stress and accessibility difficulties among people with disabilities in Greece and/or by the beneficial role of a possible engagement of some non-working individuals in unpaid job positions (subsidized programs, community services). Moreover, our findings regarding the more positive mood of those with greater economic self-sufficiency, as measured by CHART- economic self-sufficiency subscale, is consistent with other studies [9, 26, 29]. This may be attributed to the enhanced accessibility to commodities and services that are needed in daily life and recreational activities, like travelling.

Our study proved that depressive disorders are associated with low levels of functional independence and QoL as well as with difficulties in several dimensions of social inclusion, in agreement with findings by Tate et al. [10]. Van Leeuwen et al. noted that mental health and life satisfaction can be considered as two separate but in a way inter-related outcome variables, while self-efficacy and neurosis are directly related to mental health and indirectly to life satisfaction [30]. According to Tate et al., there is an association between improved QoL and reduction of depressive symptoms. This association is stronger with parameters of QoL as life satisfaction and mental well-being rather than physical well-being [10].

Potential limitations of our study may be the absence of data on antidepressive pharmacological treatments or psychological support of participants, the undocumented possible current substance abuse, the self-reported data during registration, and the volunteer recruitment of the sample. Furthermore, we did not access the entire SCI population in Greece, since there are no official national records. Thus our sample was recruited from a subtotal of this population, and in this manner, it cannot provide accurate estimates of the prevalence of depressive mood among the target population. The recruitment process (receiving data by public and private inpatient rehabilitation institutions from all across Greece), and the male/female ratio (4:1), that is consistent with the internationally found ratio, provide some indication of representativeness but cannot confirm that our sample is representative.

More research is needed to investigate the potential connection between depressive disorders and other demographic and socioeconomic risk factors. Future research should be conducted to develop external interventions for the prevention of depression and new policies for the early detection of emotional disorders in people with SCI in order for them to be used in clinical settings.

Conclusions

The present study assessed the rates of depression in the Greek SCI population. It also highlighted the association of probable depression with reduced QoL, social reintegration, and functional capacity. Additionally, we identified several risk factors associated with high levels of depressive mood after SCI that clinicians must be aware of in order to classify people consistent with depression risk. Systematic monitoring for probable depression in individuals who have not entered tertiary education, individuals with pressure ulcers, or those who suffer from intense pain, and especially from both neuropathic and nociceptive pain, seems to be of critical importance.

Determining the predictors of depressive mood in the SCI population is helpful in the adoption of optimal intervention methods and health care policies to impede depression occurrence in subgroups of patients who are more likely to present such symptoms. Our results are also helpful to further research, which may focus on the effectiveness of clinical protocols for the prevention and treatment of depression in this SCI population. Finally, our conclusions indicate that reducing the prevalence of depressive symptoms among individuals with SCI may have beneficial effects on QoL, social inclusion, and independence, as all those three factors are strongly associated with emotional well-being.

References

Scivoletto G, Petrelli A, Di Lucente L, Castellano V. Psychological investigation of spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:516–20.

Savic G, DeVivo MJ, Frankel HL, Jamous MA, Soni BM, Charlifue S. Causes of death after traumatic spinal cord injury-a 70-year British study. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:891–97.

Williams R, Murray A. Prevalence of depression after spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:133–40.

Hoffman JM, Bombardier CH, Graves DE, Kalpakjian CZ, Krause JS. A longitudinal study of depression from 1 to 5 years after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:411–8.

Smith BM, Weaver FM, Ullrich PM. Prevalence of depression diagnoses and use of antidepressant medications by veterans with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86:662–71.

Dorsett P, Geraghty T. Depression and adjustment after spinal cord injury: a three year longitudinal study. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2004;9:43–56.

Craig AR, Hancock KM, Dickson HG. Spinal cord injury: a search for determinants of depression two years after the event. Br J Clin Psychol. 1994;33:221–30.

Saunders LL, Krause JS, Focht KL. A longitudinal study of depression in survivors of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:72–7.

Krause JS, Kemp B, Coker J. Depression after spinal cord injury: relation to gender, ethnicity, aging, and socioeconomic indicators. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:1099–109.

Tate D, Forchheimer M, Maynard F, Dijkers M. Predicting depression and psychological distress in persons with spinal cord injury based on indicators of handicap. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;73:175–83.

Tsai IH, Graves DE, Lai CH, Hwang LY, Pompeii LA. Association of internet use and depression among the spinal cord injury population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:236–43.

Polyzos N, Karakolias S, Dikeos C, Theodorou M, Kastanioti C, Mama K, et al. The introduction of Greek Central Health Fund: has the reform met its goal in the sector of Primary Health Care or is there a new model needed? BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:583.

Niessen M, Peschar J. Comparative research on Education: overview, strategy and application in Eastern and Western Europe. Budapes: Elsevier; 2013.

Tzanos IA, Mitsiokapa E, Megaloikonomos P, Igoumenou V, Panagopoulos G, Papathanasiou J, et al. Social reintegration and quality of life after spinal cord injury: the Greek paradigm. J Biomed. 2016;1:36–43.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves D, Jha A et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (Revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:535–46

Bryce TN, Budh CN, Cardenas DD, Dijkers M, Felix ER, Finnerup NB, et al. Pain after spinal cord injury: an evidence-based review for clinical practice and research. Report of the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Spinal Cord Injury Measures Meeting. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:421–40.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Sakakibara BM, Miller WC, Orenczuk SG, PsyD, Wolfe DL. SCIRE Research Team. A systematic review of depression and anxiety measures with individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:841–51.

Bombardier CH, Kalpakjian CZ, Graves DE, Dyer JR, Tate DG, Fann JR. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in assessing major depressive disorder during inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:1838–45.

Kalpakjian CZ, Bombardier CH, Schomer K, Brown PA, Johnson KL. Measuring depression in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:6–24.

Whiteneck GG, Charlifue SW, Gerhart KA, Overholser JD, Richardson GN. Quantifying handicap: a new measure of long-term rehabilitation outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:519–26.

Development of the World Health Organization. WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8.

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E, Ring H, Tamir A. SCIM-spinal cord independence measure: a new disability scale for patients with spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:850–6.

Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Krause JS, Tulsky D, Tate DG. Symptoms of major depression in people with spinal cord injury: implications for screening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1749–56.

Krause JS, Saunders LL, Reed KS, Coker J, Zhai Y, Johnson E. Comparison of the Patient Health Questionnaire and the Older Adult Health and Mood Questionnaire for self-reported depressive symptoms after spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:440–8.

Khazaeipour Z, Taheri-Otaghsara SM, Naghdi M. Depression following spinal cord injury: its’ relationship to demographic and socioeconomic indicators. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2015;21:149–55.

Modirian E, Pirouzi P, Soroush M, Karbalaei-Esmaeili S, Shojaei H, Zamani H. Chronic pain after spinal cord injury: results of a long-term study. Pain Med. 2010;11:1037–43.

Kalpakjian CZ, Albright KJ. An examination of depression through the lens of spinal cord injury. Women’s Health Issues. 2006;16:380–8.

Botticello AL, Chen Y, Cao Y, Tulsky DS. Do communities matter after rehabilitation? The effect of socioeconomic and urban stratification on well-being after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:464–71.

van Leeuwen CM, Post MW, Westers P, van der Woude LH, de Groot S, Sluis T, et al. Relationships between activities, participation, personal factors, mental health, and life satisfaction in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:82–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tzanos, I., Mavrogenis, A., Gioti, K. et al. Depressive mood in individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) living in Greece. Spinal Cord 56, 883–889 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0093-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0093-z

This article is cited by

-

Sexual dysfunction in women with spinal cord injury living in Greece

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2021)

-

Factors influencing depression in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury and caregivers’ perceived burden in a low-income country: a cross-sectional study

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Investigating the Relationship between Religious Beliefs with Care Burden, Stress, Anxiety, and Depression in Caregivers of Patients with Spinal Cord Injuries

Journal of Religion and Health (2020)