Abstract

Study design

A longitudinal study.

Objectives

To describe the prevalence and stability of self-reported spasticity severity in adults with chronic spinal cord injury (SCI) over a 3-year timeframe and examine predictors of severity and change in spasticity severity.

Setting

The data were collected by mail at a medical university in the Southeastern United States.

Methods

A total of 1790 adults with chronic SCI responded to two self-report assessments, one between 2007 and 2009 (baseline) and another between 2011 and 2014 (follow-up). Average spasticity severity was measured on a numeric rating scale from 0 (no spasticity) to 10 (spasticity as bad as you can imagine). Frequency of prescription medication use for spasticity in the past year was also reported (never, sometimes/weekly, daily).

Results

About 82.5% of participants had spasticity at baseline and 86.5% at follow-up. There was a significant change in spasticity severity (0.9 ± 2.3; p < 0.001), corresponding to a 31% increase in mean severity. Overall, the frequency of medication use did not significantly change. At baseline, 55.6% of participants reported using medications for spasticity in the past year; 54.9% reported use at follow-up. Variables significantly associated with spasticity severity included race/ethnicity, age, and spasticity medication use.

Conclusions

Spasticity is highly prevalent after SCI. Though severity is mild on average, a statistically significant increase was observed over a relatively short natural timeframe. The changes observed in spasticity severity categories (mild, moderate, severe) highlight the need to monitor spasticity in individuals with chronic SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spasticity is a common secondary health condition in persons with spinal cord injury (SCI), often presenting within months after injury and persisting for years following [1,2,3]. Spasticity is a symptom of upper motor neuron damage and is most often defined as “a motor disorder characterized by a velocity-dependent increase in the tonic stretch reflex (muscle tone) with exaggerated tendon jerks, resulting from hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex” [4] (p. 485). Broader definitions, including associated symptoms of increased muscle tone during passive movements, intermittent or sustained involuntary muscle activation (spasms), clonus, and increased tendon reflexes, are also used [1,2,5,6,7]. A general lack of agreement remains concerning the precise definition, ideal assessment techniques, and best treatment options (e.g., physical rehabilitation techniques, pharmacological or surgical interventions, or stimulation) [2,8,9,10,11]. To date, there is insufficient evidence to provide a recommendation for the most effective prescription medication or optimal treatment strategy [12,13,14].

The data suggest 65–78% of persons with chronic SCI experience spasticity [1,6,15,16,17], though rates as low as 40% have been reported [18]. Problematic spasticity, defined as requiring anti-spasticity medication [19], limiting function or activities of daily living [15,20], or simply being perceived as problematic [1], has been reported by approximately 25–35% of individuals with SCI [1,15,19,20,21]. Increased rates of spasticity are found in individuals with higher-level (cervical or thoracic) injuries as well as in those with incomplete injuries [1,6,15,16,17,18,19,22]. While many studies have reported on the prevalence of spasticity, data regarding self-reported severity of spasticity are lacking.

Only a handful of prospective studies have assessed changes in spasticity, primarily focused on the first few years after injury [15,19,22,23]. In some studies, the prevalence was reported to decrease over time [18,20,21,22], while others have found the odds of reporting spasticity to increase over time [24]. In contrast with the studies of new SCI, there are few longitudinal studies that have assessed self-reported changes in spasticity severity in persons with chronic SCI. Considering the current state of the literature, there is a need for large cohort studies to assess the severity of spasticity in persons with chronic SCI, focusing on patterns and predictors of change over a natural time course, while also considering usage of prescription medications for spasticity.

Purpose

Our purpose was to conduct an analysis of longitudinal data to assess the prevalence and stability of self-reported spasticity over two points of time in a large sample of adults with chronic SCI living in the United States. We assessed: (1) self-reported average spasticity severity, measured on a numeric rating scale (NRS) of 0–10 on two occasions separated by an average of 3.3 years, (2) the frequency of medication use to treat spasticity, and (3) predictors of change in spasticity severity.

Methods

These data stem from a 15-year longitudinal research project designed to identify the natural course of changes in health and risk of secondary health conditions, using a theoretical risk and prevention model which describes demographic, psychological, environmental, and behavioral predictors of health [25,26]. We utilized data collected from the two most recent times of data collection, focusing on spasticity items common to both times of measurement.

Participants

Eligibility criteria included: (1) adult (≥ 18 years), (2) traumatic SCI with residual deficits, and (3) minimum of 12 months post-injury. Participants were recruited from a large specialty hospital in the Southeast United States designated as an SCI Model System center and were selected from the following sources: the Model Systems catchment cases, Model Systems registry, and outpatient records. This is part of a larger prospective cohort study, the SCI Longitudinal Health Study, initiated in 1997–1998 with a cohort of 1386 participants [27,28]. A second cohort was added in 2007–2009.

The current analysis focuses on spasticity, using variables administered in 2007–2009 and 2011–2014. At the time of the baseline spasticity data collection in 2007–2009 (baseline for the purpose of the current analysis), 2547 participants completed the self-report assessment (SRA). Of the 2547 participants who participated at baseline, 70% (n = 1790) completed the SRA again at follow-up. There were 757 participants who did not respond at follow-up (n = 235 deceased, 495 non-responders/lost to follow-up, n = 19 requested no further contact, and n = 8 ineligible due to reporting full recovery).

An attrition analysis comparing those who responded at both baseline and follow-up (n = 1790) versus those who did not respond again at follow-up (n = 757) found significant differences. Individuals with greater spasticity (p = 0.01) and those who used medications more frequently at baseline (p = 0.0005) were more likely to be non-responders at follow-up. Furthermore, men were more likely to be non-responders at follow-up (p = 0.02). None of the other demographic or injury characteristics were significantly related to participation status at follow-up.

Procedures

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained prior to initiating data collection. The baseline spasticity assessment was completed in 2007–2009 with the second assessment completed between 2011 and 2014 (follow-up). Data were collected by mail-in SRA, with similar procedures followed at each time of measurement. Participants were mailed preliminary letters explaining the study and notifying them of forthcoming study materials. The initial study packet was mailed to participants 4–6 weeks later. Non-responders were mailed a second set of materials and received a follow-up phone call. Those who expressed interest in participating during the phone call were mailed a third study packet. Participants were offered $50 in remuneration at each time of measurement.

Measures

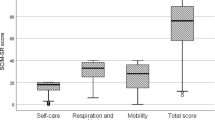

Spasticity was defined in the SRA as “muscle spasms or involuntary muscle movement”. Participants were asked to rate the severity of their spasticity, on average (no timeframe was given), on an NRS from 0 (no spasticity) to 10 (spasticity as bad as you can imagine). An NRS is a quick and effective self-report tool commonly used to assess severity of pain [29,30] and is considered a valid and reliable measure of spasticity severity in individuals with multiple sclerosis [31,32]. A 30% decrease, or −1.27 raw change, in 0–10 NRS spasticity score is considered a clinically important difference (CID), while an 18% or −0.9 raw score change is regarded as the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) [32]. These CIDs were determined by comparing the mean value for the change in NRS score with the Patient Global Impression of Change categories of “much improved” or better and “minimally improved” or better [32]. Spasticity severity was categorized as follows: 0 = no spasticity, 1–3 = mild, 4–6 = moderate, and 7–10 = severe, based on the cutoff scores for the pain NRS [33] and those used in a recent publication [17]. Participants also responded to a question regarding the frequency of prescription medication use for spasticity in the past year (never, sometimes/weekly, daily).

Demographic and injury variables included gender, age at assessment, race/ethnicity, years since injury, level and severity of injury, and ambulatory status. Due to the nature of the SRA and lack of clinical data regarding American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) classifications, we used ambulatory status as a proxy variable for ASIA Impairment Scale D, in accordance with previous publications [34,35,36]. Injury severity was categorized as follows: (1) C1–C4, non-ambulatory; (2) C5–C8, non-ambulatory; (3) non-cervical, non-ambulatory; and (4) all those ambulatory.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using SAS software Version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the participant sample, spasticity severity, and frequency of medication use. T-tests and the χ 2 statistic were used to compare the characteristics of those who completed both assessments (n = 1790) with those who did not complete the SRA at follow-up (n = 757).

A paired t-test was used to examine changes in average spasticity scores between the two time points. A Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used to examine the changes in spasticity medication use, as measured on a 3-point ordinal scale (never, sometimes/weekly, daily).

A Generalized Linear Model (GLM) was used to examine predictors of baseline spasticity severity as well as change in spasticity severity. The GLM is a flexible linear regression model allowing for simultaneous estimates of both categorical and continuous response variables. Our main outcomes were spasticity severity and change in severity from baseline to follow-up. The baseline GLM examined cross-sectional associations between spasticity severity and selected covariates, including frequency of spasticity medication use as a control variable. The change model examined predictors of change in spasticity severity and included both frequency of spasticity medication use at baseline and changes in use as statistical control variables. All models were expanded to include fixed/non-time varying covariates, including sex, race/ethnicity, age at baseline, years since injury at baseline, and injury severity.

Results

A total of 1790 participants completed the SRA at both time points, with an average of 3.3 ± 0.7 years between assessments. The majority were White (73.2%) males (74.1%). Mean age at baseline was 45.4 ± 13.6 years, and participants were on average 12.6 ± 9.6 years post-injury (Table 1).

Spasticity severity and change

There was a significant difference in the proportion of individuals who reported spasticity at baseline and follow-up (McNemar’s p < 0.001). Spasticity was reported by 82.5% of participants at baseline and 86.5% at follow-up. Of these, 45.2% reported mild spasticity (NRS 1–3), 27.2% reported moderate severity (4–6), and 10.1% reported severe spasticity (7–10) at baseline. At follow-up, the rates were 37%, 30.3%, and 19.2%, respectively.

The mean spasticity severity at baseline was 2.9 ± 2.4; spasticity severity was 3.8 ± 2.7 at follow-up. The change in spasticity scores was significant (0.9 ± 2.3; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.8–1.0; p < 0.001). This change corresponds to a mean 31% increase in spasticity severity. The majority of participants (54.3%) reported an increase in average spasticity severity. In this subgroup of 934 individuals, a significant 2.5 ± 1.6 increase (p < 0.001; 95% CI 2.4–2.6) was observed, from average severity scores of 2.6 ± 2.0 to 5.1 ± 2.5. Twenty percent of participants reported a decrease in spasticity severity. In these 343 individuals, the change was −2.2 ± 1.5 (p < 0.001, 95% CI −2.4 to −2.0), from mean severity scores of 4.8 ± 2.3 to 2.6 ± 2.1. One-quarter of participants (n = 442) reported the same severity of spasticity at both time points (mean 2.2 ± 2.6); 171 of these participants reported no spasticity (NRS = 0) at baseline.

Using only information from participants with valid spasticity scores at both time points (n = 1719), we assessed change in spasticity severity categories between the two time points. The descriptive results are given in Table 2. The spasticity category remained consistent for the majority of participants who had none, mild, or severe spasticity. We found a greater occurrence of change among participants who reported moderate levels of spasticity at baseline, with only 42.3% reporting moderate severity again at follow-up.

Prescription medication use for spasticity

There was no significant change in the frequency of prescription medication use to treat spasticity (Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test, p = 0.352). At baseline, 55.6% of participants reported using prescription medications for spasticity in the past year; 54.9% also reported use at follow-up. Of these, 8.8% reported sometimes/weekly usage of medications at both time points. Daily usage of mediations was reported by 46.8% at baseline and 46.1% at follow-up. Of the 1733 participants who responded to the spasticity medication question at both assessments, 80% reported no change in the frequency of use. Roughly, 10% of participants reported either a decrease or an increase in the frequency of use. The majority of individuals who never used or used medications daily maintained their usage pattern (Table 3). We observed a greater percentage of change in medication usage among individuals who reported sometimes/weekly use at baseline.

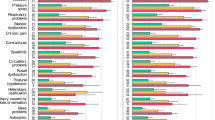

General Linear Model

Results from the baseline GLM showed that race/ethnicity, age, and frequency of prescription medication use for spasticity were significantly associated with spasticity severity (Table 4). Specifically, compared to individuals who were non-Hispanic White, those who were non-Hispanic African American/Black and those who were identified as “other” reported greater spasticity severity. Age was negatively associated with spasticity severity. Compared to daily usage, never taking medications for spasticity was associated with lower spasticity severity scores. However, with the exception of medication indicators, none of the injury or demographic variables were significantly related to change in spasticity severity (Table 4).

Discussion

Our purpose was to investigate the prevalence and stability of self-reported average spasticity severity and prescription medication use for spasticity and to examine the predictors of spasticity severity and change in severity over time. Consistent with previous findings, we found spasticity to be highly prevalent in persons with chronic SCI. We also found significant increases in self-reported average spasticity severity over time, although reported levels of spasticity decreased for some individuals. Therefore, spasticity ratings fluctuated over time, with the average change being an increase. We were not able to identify significant predictors of change, other than medication changes, which would be expected and were included as a statistical control.

Our reported rates of spasticity are higher than what has been previously published [1,6,15,16], with roughly 83% of participants reporting spasticity at baseline and 87% at follow-up. The finding of increased prevalence over time is contrary to the majority of longitudinal assessments. This may be explained, in part, by the time elapsed since injury, as earlier reports have focused primarily on the first few years after injury. For example, Johnson et al. [21] assessed self-reported problematic spasticity and found a decrease in the 5-years after injury, with rates remaining over 25%. Adriaansen et al. [22] also found a significant decrease in the occurrence of problematic spasticity between 1 (36%) and 2 years (23%); at 5-years post-discharge, 31% of participants reported problematic spasticity. A recent study of the prevalence of self-report spasticity in community-living adults in Canada found higher and relatively steady rates of 59%, 63%, and 61% at 1, 2, and 5-years post-injury, respectively [19]. We do not know how much differences in spasticity definitions and assessment contribute to the differences between studies. In line with our findings, Hitzig et al. [24] found that the odds of reporting spasticity increased over a roughly 7-year timeframe. Similar to our study, the mean time since injury was 12 years. These findings suggest that individuals with longer duration of injury may be experiencing changes in spasticity that are different from those observed in the first few years after injury. Continued research is necessary to determine why these changes are observed. Important factors to consider may include the presence and time course of secondary health conditions such as pressure ulcers or infection and the utilization of health-care services (i.e., differences in routine medical care and/or prescription monitoring in the years after injury).

There is currently little literature regarding self-reported spasticity severity in individuals with chronic SCI. Recently, Andresen et al. [17] assessed spasticity using an NRS (0–10). They found that 71% of participants reported spasticity. Among these, the average intensity of muscle stiffness was 3.9 ± 2.4, similar to the average spasticity severity we report at follow-up (3.8 ± 2.7). Similar distributions of intensity were also observed, with a greater percentage of individuals reporting mild (NRS 1–3) and moderate (NRS 4–6) spasticity, compared to severe (NRS 7–10). In their sample, the observed rates of mild, moderate, and severe muscle stiffness were 33%, 23%, and 12%, respectively [17]. We cannot comment on the degree to which the differences in terminology or methodology impact the comparisons to our findings.

Although average spasticity at both time points was mild, our findings suggest a significant increase in spasticity severity. On average, we found a nearly 1-point increase, corresponding to a 31% mean increase in average spasticity severity over time. Subgroup analysis of those who reported increased or decreased severity found, on average, 2.5- and −2-point changes, respectively. At the individual level, in those with multiple sclerosis and clinical diagnoses of spasticity, a 30% improvement or −1.27 raw change in NRS spasticity score is considered a CID, and an 18% improvement or −0.9 raw score change is the MCID [32]. It is important to note that the established CID and MCID are intended to be measured and interpreted at an individual level, following interventions aimed to improve spasticity, whereas we are reporting on mean natural changes over time, based on self-report, not clinically diagnosed spasticity. We present the CID and MCID as a reference only, as the cutoff values have yet to be determined for individuals with SCI. Our findings suggest that in the absence of controlled intervention, a significant percentage of individuals are experiencing clinically meaningful changes in spasticity severity over time.

Considering the descriptive changes within the severity categories, individuals who reported no, mild, or severe spasticity tended to report less change than those with moderate severity. We believe it is important to track changes in spasticity severity in individuals with chronic SCI, specifically those with spasticity of moderate severity, as we observed the greatest shift toward severe spasticity in this subgroup. Continued monitoring of spasticity severity and careful management may attenuate the risk of adverse side effects (e.g., contracture, pain, falls, diminished quality of life), while also promoting the beneficial aspects of spasticity (e.g., functional usefulness or help with activities of daily living).

While there was a significant increase in both the percentage of individuals with spasticity and the average reported severity of spasticity, there was no significant change in the percentage of individuals who used prescription medications for spasticity. We found that the majority of individuals (~55%) took prescription medications for spasticity, slightly higher than previous findings, which estimate 35–46% of persons with chronic SCI use prescription medications (e.g., baclofen, dantrolene, diazepam, or tizanidine) to manage their symptoms [6,17,19,23]. Considering the frequency of use, we found that roughly 9% of participants took their medications only sometimes or weekly. Within this group, we found greater variation in use from baseline to follow-up. These data hint at prescription non-adherence, as spasticity medications are typically prescribed for daily usage, and also raise questions about the causes of change. Data suggest that general adherence to oral prescription medications for spasticity is poor [37]. Although the reasoning for the observed pattern of use was not evaluated, it is important to consider that lack of perceived effectiveness or presence of adverse side effects may affect the frequency of usage. While we did not observe an overall change in the frequency of medication use, there may have been changes in frequency of use between sometimes and weekly use, changes in prescription medications, and dosages. Our findings suggest that changes in use were associated with changes in spasticity severity, thus it is important to monitor and promote adherence to medication use for spasticity.

Limitations

Although this study contributes to the understanding of spasticity after SCI, there were limitations. First, as the data are from an SRA, there are no clinical data to classify the severity of injury (i.e., American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Score (AIS)). Second, the SRA definition of spasticity was “muscle spasms or involuntary muscle movements”, and did not include muscle stiffness or other symptoms commonly included in spasticity definitions. Additionally, the NRS data reflect the individual’s evaluation of their average spasticity severity, rather than comprehensive clinical assessments of spasticity. Although the NRS has been shown to be a valid and reliable tool, some authors have urged caution in using this tool, specifically for interpreting pain severity [38]. Therefore, the findings must be interpreted within the measurement context. Third, the data regarding prescription medication use reflect only self-reported frequency of usage. The SRA did not address prescribed usage, adherence, or the specific prescription medications used. Fourth, although the sample size was large, there is always attrition in longitudinal studies. This sample included only individuals who completed the SRA at both follow-ups. The attrition analysis showed that individuals with greater spasticity and those who used medications more frequently at baseline were more likely to be non-responders at follow-up. Lastly, it is important to remember that the data and analyses do not permit inferences of causality. Future experimental research, controlling for medication use, may better answer questions regarding the association between spasticity severity and patterns of medication use.

Future directions

Continued longitudinal research, incorporating additional time points and individuals with longer duration of injury, will be necessary to determine if the trends toward increasing spasticity prevalence and severity remain over time. Owing to the nature of our SRA, we are limited in our ability to explain the factors contributing to the increase; further clinical rehabilitation research could help to identify additional factors that may be of importance. Additionally, continued study is necessary to help understand the frequency of medication usage among those with spasticity. It would be beneficial to determine if the observed changes in medication use were recommended by a health-care professional or self-directed, and to monitor use to ensure the changes do not result in increased spasticity severity.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that spasticity is highly prevalent and spasticity severity increased over a roughly 3-year interval. However, there was no significant change in the rates of prescription medication usage for spasticity. Our findings highlight the importance for individuals with SCI to discuss severity of spasticity with their care providers and to be counseled on treatment options and prescription adherence.

References

Skold C, Levi R, Seiger A. Spasticity after traumatic spinal cord injury: nature, severity, and location. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1548–57.

Adams MM, Hicks AL. Spasticity after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:577–86.

Jensen MP, Truitt AR, Schomer KG, Yorkston KM, Baylor C, Molton IR. Frequency and age effects of secondary health conditions in individuals with spinal cord injury: a scoping review. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:882–92.

Lance JW. Symposium synopsis. In: Feldman RG, Young RR, Koella WP, editors. Spasticity: Disordered Motor Control. Miami, FL: Symposia Specialists; 1980. p. 485.

Merritt JL. Management of spasticity in spinal cord injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981;56:614–22.

Maynard FM, Karunas RS, Waring WP 3rd. Epidemiology of spasticity following traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:566–9.

Dietz V. Spastic movement disorder. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:389–93.

Dietz V. Spasticity-spastic movement disorder. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:588.

Hsieh JT, Wolfe DL, Miller WC, Curt A. Spasticity outcome measures in spinal cord injury: psychometric properties and clinical utility. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:86–95.

Burridge JH, Wood DE, Hermens HJ, Voerman GE, Johnson GR, van Wijck F, et al. Theoretical and methodological considerations in the measurement of spasticity. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:69–80.

Pandyan AD, Gregoric M, Barnes MP, Wood D, Van Wijck F, Burridge J, et al. Spasticity: clinical perceptions, neurological realities and meaningful measurement. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:2–6.

Taricco M, Pagliacci MC, Telaro E, Adone R. Pharmacological interventions for spasticity following spinal cord injury: results of a Cochrane systematic review. Eura Medicophys. 2006;42:5–15.

Naro A, Leo A, Russo M, Casella C, Buda A, Crespantini A, et al. Breakthroughs in the spasticity management: are non-pharmacological treatments the future? J Clin Neurosci. 2017;39:16–27.

Chang E, Ghosh N, Yanni D, Lee S, Alexandru D, Mozaffar T. A review of spasticity treatments: pharmacological and interventional approaches. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med. 2013;25:11–22.

Levi R, Hultling C, Seiger A. The Stockholm Spinal Cord Injury Study: 2. Associations between clinical patient characteristics and post-acute medical problems. Paraplegia. 1995;33:585–94.

Hitzig SL, Campbell KA, McGillivray CF, Boschen KA, Richards R, Craven BC. Secondary health complications in an aging Canadian spinal cord injury sample. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87:545–55.

Andresen SR, Biering-Sorensen F, Hagen EM, Nielsen JF, Bach FW, Finnerup NB. Pain, spasticity and quality of life in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury in Denmark. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:973–9.

Noreau L, Proulx P, Gagnon L, Drolet M, Laramee MT. Secondary impairments after spinal cord injury: a population-based study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79:526–35.

Holtz KA, Lipson R, Noonan VK, Kwon BK, Mills PB. Prevalence and effect of problematic spasticity following traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1132–8.

Adriaansen JJ, Ruijs LE, van Koppenhagen CF, van Asbeck FW, Snoek GJ, van Kuppevelt D, et al. Secondary health conditions and quality of life in persons living with spinal cord injury for at least ten years. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48:853–60.

Johnson RL, Gerhart KA, McCray J, Menconi JC, Whiteneck GG. Secondary conditions following spinal cord injury in a population-based sample. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:45–50.

Adriaansen JJ, Post MW, de Groot S, van Asbeck FW, Stolwijk-Swuste JM, Tepper M, et al. Secondary health conditions in persons with spinal cord injury: a longitudinal study from one to five years post-discharge. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45:1016–22.

van Cooten IP, Snoek GJ, Nene AV, de Groot S, Post MW. Functional hindrance due to spasticity in individuals with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation and 1 year thereafter. Spinal Cord. 2015;53:663–7.

Hitzig SL, Campbell KA, McGillivray CF, Boschen KA, Craven BC. Understanding age effects associated with changes in secondary health conditions in a Canadian spinal cord injury cohort. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:330–5.

Krause JS. Secondary conditions and spinal cord injury: a model for prediction and prevention. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 1996;2:217–27.

Krause JS, Saunders LL, DiPiro ND, Reed KS. Theoretical risk and prevention model for secondary health conditions and mortality: 15 years of research. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2013;19:15–24.

Krause JS, Saunders LL. Health, secondary conditions, and life expectancy after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:1770–5.

Krause JS, Saunders LL. Socioeconomic and behavioral risk factors for mortality: do risk factors observed after spinal cord injury parallel those from the general USA population? Spinal Cord. 2012;50:609–13.

Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, et al. Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:1073–93.

Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149–58.

Anwar K, Barnes MP. A pilot study of a comparison between a patient scored numeric rating scale and clinician scored measures of spasticity in multiple sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation. 2009;24:333–40.

Farrar JT, Troxel AB, Stott C, Duncombe P, Jensen MP. Validity, reliability, and clinical importance of change in a 0-10 numeric rating scale measure of spasticity: a post hoc analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Ther. 2008;30:974–85.

Forchheimer MB, Richards JS, Chiodo AE, Bryce TN, Dyson-Hudson TA. Cut point determination in the measurement of pain and its relationship to psychosocial and functional measures after traumatic spinal cord injury: a retrospective model spinal cord injury system analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:419–24.

Krause JS, Saunders LL. Risk of mortality and life expectancy after spinal cord injury: the role of health behaviors and participation. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2010;16:53–60.

Saunders LL, Krause JS. Injuries and falls in an aging cohort with spinal cord injury: SCI Aging Study. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2015;21:201–7.

Krause JS, Clark JM, Saunders LL. SCI Longitudinal Aging Study: 40 years of research. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2015;21:189–200.

Halpern R, Gillard P, Graham GD, Varon SF, Zorowitz RD. Adherence associated with oral medications in the treatment of spasticity. PM R. 2013;5:747–56.

Dijkers M. Comparing quantification of pain severity by verbal rating and numeric rating scales. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:232–42.

Acknowledgements

The contents of this publication were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RT5003). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this publication do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DiPiro, N.D., Li, C. & Krause, J.S. A longitudinal study of self-reported spasticity among individuals with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 56, 218–225 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0031-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0031-5