Abstract

Background

Multiparametric MRI localizes cancer in the prostate, allowing for MRI guided biopsy (MRI-GB) 43 alongside transrectal ultrasound-guided systematic biopsy (TRUS-GB). Three MRI-GB approaches exist; visual estimation (COG-TB); fusion software-assisted (FUS-TB) and MRI ‘in-bore’ biopsy (IB-TB). It is unknown whether any of these are superior.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to address three questions. First, whether MRI-GB is superior to TRUS-GB at detecting clinically significant PCa (csPCa). Second, whether MRI-GB is superior to TRUS-GB at avoiding detection of insignificant PCa. Third, whether any MRI-GB strategy is superior at detecting csPCa.

Methods

A systematic literature review from 2015 to 2019 was performed in accordance with the START recommendations. Studies reporting PCa detection rates, employing MRI-GB and TRUS-GB were included and evaluated using the QUADAS-2 checklist. 1553 studies were found, of which 43 were included in the meta-analysis.

Results

For csPCa, MRI-GB was superior in detection to TRUS-GB (0.83 vs. 0.63 [p = 0.02]). MRI-GB was superior in detection to TRUS-GB at avoiding detection of insignificant PCa. No MRI-GB technique was superior at detecting csPCa (IB-TB 0.87; COG TB 0.81; FUS-TB 0.81, [p = 0.55]). There was significant heterogeneity observed between the included studies.

Conclusions

In patients with suspected PCa on MRI, MRI-GB offers superior rates of csPCa detection and reduces detection of insignificant PCa compared to TRUS-GB. No individual MRI-GB technique was found to be better in csPCa detection. Prospective adequately powered randomized controlled trials are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is suspected after either an abnormal digital rectal examination (DRE) or raised prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, or both. Once suspected, PCa requires tissue confirmation. Traditionally the method to achieve this is the systematic transrectal, ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy (TRUS-GB). The introduction of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) allows the identification of discrete areas of abnormal tissue that have a higher likelihood for harbouring clinically significant prostate cancer (csPCa). Thus, this confers a higher sensitivity than TRUS-biopsy alone, approximately 87% to 93%, depending on the definition of csPCa [1]. Current guidance now recommends mpMRI to be carried out prior to the first biopsy [2]. Its use prior to biopsy has grown rapidly, to near 100% in the UK [3]. The ability of mpMRI to localize disease in the prostate allows for targeted or guided biopsy (MRI-GB).

Alongside the proliferation in MRI use pre-biopsy, there is significant interest in MRI-GB [4]. For instance, there was a 20-fold increase in the use of MRI-GB in the United States in recent years [4]. Currently, there is variation in how MRI-GB is performed. Three major technical approaches to MRI-GB are generally employed. First, visual estimation or cognitive targeting (COG-TB) in which a region of interest (ROI) is identified prior to biopsy and the biopsy operator estimates where it might be on an ultrasound image. Second, software-assisted fusion (FUS-TB) involves identifying and contouring ROIs on MR-images before biopsy and overlaying these with the prostate contours on ultrasound images during the biopsy procedure. This can be elastic (deformable registration to reflect deformation of the prostate) or rigid (an overlay of MRI to ultrasound images with some adjustment of rotation). Last, in-bore biopsy (IB-TB) (or in-gantry) involves performing the biopsy in the MRI scanner, guided by MR imaging taken immediately after each needle placement.

There is currently no consensus on whether any of these approaches is superior in terms of cancer detection. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to address first, whether MRI-GB is superior to TRUS-GB at detecting clinically significant PCa (csPCa). Second, if MRI-GB is better at not detecting insignificant PCa, and third if any of the three MRI-GB strategies is superior at detecting csPCa.

Patients and methods

Search strategy

The current systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to update the results published by Wegelin et al., 2017 [5] and followed the guidelines suggested by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement [6]. We employed the identical search strategy, using the keywords “Prostate OR Prostatic Neoplasm” AND “Biopsy” AND “Magnetic Resonance Imaging OR Image-Guided Biopsy”. The search was performed in PubMed, Embase, and CENTRAL databases with the language restricted to English. As the review by Wegelin et al. [6] included studies published before 15/12/2015, the time frame was restricted to 15/12/2015 to 29/07/2019. The review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020179508). All references were imported in ‘Zotero’ reference manager.

Study selection

For the purposes of this meta-analysis, we included studies reporting PCa detection rates among patients at risk of PCa according to their clinical parameters, of IB-TB, or FUS-TB, or COG-TB alongside TRUSGB. The exclusion criteria were: inclusion of patients with previously diagnosed PCa, on active surveillance, or mixed populations where this group were not reported on separately. We also excluded studies if data for patients biopsy status was not reported, or, if a previous negative biopsy population was included, we excluded studies where data for with the population no or at least one negative prior biopsy were not separately reported upon. Finally, we excluded studies if the MRI acquisition was not in accordance with the 2012 ESUR guidelines [7], or if studies used alternative targeted biopsy strategies such as multiparametric ultrasound.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the studies was evaluated using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool [8]. The assessment was performed by a single reviewer (AP) and checked by a second (HUA). QUADAS-2 is a tool recommended for use in systematic reviews to evaluate the risk of bias and the applicability of primary diagnostic accuracy studies [8].

Data extraction

The initial data extraction was performed by a single reviewer (AP) in accordance with the START recommendations [9] and double-checked by a second (HUA). Data collected were: the recruitment method (clinical parameters); investigated population characteristics and sample size; the method of MRI acquisition and evaluation; MRI findings and/or PI-RADS score; the threshold for MRI positivity; biopsy method; whether the comparison between these two methods was made; the definition of csPCa and finally the detection rates of csPCa, and clinically insignificant PCa per patient and per core, where available.

Data analysis

The analysis was conducted to answer our three stated aims. For this, we first focused only on studies that reported detection rates with both MRI-GB and TRUS-GB. Therefore, the final sample size of the study population refers to the number of patients that underwent both techniques. We calculated the effect sizes with their corresponding measures of variation prior to performing the meta-analysis.

We combined the data of all studies that reported employing any type of MRI-GB and compared it with TRUS-GB. It was obligatory that the studies reported results of both TRUS-GB and MRI-GB separately. The main accuracy measure – cancer detection rate (CDR) - was calculated by dividing the number of patients with detected cancer by TRUS-GB (or MRI-GB), with the total number of patients who were detected with cancer by the combination of TRUS-GB and MRI-GB. Relative CDR was expressed as the relative ratio between the CDR of MRI-GB and TRUS-GB. The standard error of each of the accuracy statistics was obtained by employing the formula for the standard error of a relative risk without taking the paired nature into account because not all studies reported their data in a paired format [10].

Superiority of clinically insignificant PCa detection was determined by comparison of the diagnostic yield (the likelihood that the biopsy procedure provides such a diagnosis) of each approach. In this respect, a lower number is advantageous and therefore the technique was regarded as ‘superior’. The yield of detecting clinically insignificant PCa (defined by each included study) was calculated by dividing the number of patients with insignificant PCa (the number of patients with any PCa minus the number of patients with csPCa) with the total number of patients that underwent biopsy. The relative yields were calculated by dividing the yield of MRI-GB with the yield of TRUS-GB. We pooled the estimates by conducting random-effects meta-analysis on precalculated effect sizes with metagen function of the meta package (R studio Version1.2.1335), using the generic inverse variance method and Sidik-Jonkman as a between-study-variance estimator. We assessed the between-study heterogeneity with Cochrane’s Q and I2 tests [11, 12]. I2 > 50% with p < 0.05 indicates significant heterogeneity. All analyses were done for csPCa and insignificant PCa detection rates. Publication bias was explored by inspecting the funnel plot and by employing Eggar’s test.

To answer the third review question, we used the accuracy measurements we defined above and focused on studies that reported one of the MRI-GB techniques (IB-TB or FUS-TB or COG-TB). The within-study variances were calculated based on the exact binomial distribution. The differences in sensitivity of the three techniques was compared by conducting the mixed subgroup analysis with the use of subgroup.analysis.mixed.effects function (dmetar package).

We conducted two additional subgroup analyses––one based on the methodological quality and the other based on prior biopsy history. The former pooled the effect sizes only from the studies with low risk of bias and low concerns regarding applicability. The latter included three groups (biopsy naive, negative biopsy and a mixed group of both types of patients). We additionally performed a focused analysis that excluded the mixed population group. These analyses were performed for csPCa and clinically insignificant PCa detection rates. The extracted data were computed and pre-calculated in Microsoft Excel, version 2010, while the meta-analyses were performed in R studio Version 1.2.1335 (Boston, MA, USA).

Results

Search and selection

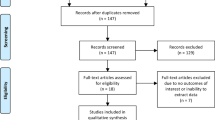

The systematic search of the three databases yielded a total of 1553 articles after removing 456 duplicates. We identified 40 new studies that assessed the diagnostic accuracy of some of the three MRI-GB techniques. Out of the identified 40 studies, 14 either did not compare the PCa detection rates between MRI-GB and TRUS-GB, or did not perform these comparisons in the same population of patients, thus they were not included in the meta-analysis. Of the remaining 26 studies, six did not report any information about the biopsy status of the study population, leaving 20 studies that were merged with the studies from the systematic review by Wegelin et al. [5]. The previous systematic review included 23/43 studies included in their meta-analysis [5] Merging new studies with those 23 from the previously published meta-analysis [5] provided a total of 43, including 8456 men, were finally included in our meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The complete selection process of the studies is presented in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1). All 20 newly identified studies, containing an additional 4675 men, were included in the meta-analysis comparing the three MRI-GB techniques.

Quality assessment

Quality was evaluated only in studies included in the meta-analysis (n = 43) (Supplementary Table 1). All studies were estimated to have low risk regarding applicability to the current review (Supplementary figure 1b). Twenty-five studies were deemed to have a high risk of selection bias [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] (Supplementary figure 1a).

Population

We observed high variability of study population size, characteristics and mean PSA level in the studies included in the meta-analysis. The sample size varied between 20 and 1003 patients, who were aged between 59.7 and 70 years, who either had no or at least one prior negative biopsy. The mean PSA level ranged from 5.7 to 11.0 ng/ml. Most studies involved a patient group with PSA < 10 ng/ml (n = 38). A 3-Tesla scanner was used in 77% of studies (n = 33). The most commonly used MRI-GB technique was FUS-TB (n = 31), followed by COG-TB (n = 8) and then IB-TB (n = 5). The definition of the threshold for performing targeted biopsy differed between studies. The PI-RADS classification system was the most frequent (n = 34), and a score of >/= 3 was the most used cutoff. The studies varied considerably in the definition of csPCa as well; therefore we performed the analysis depending on the definition given in the original articles.

MRI-GB versus TRUS-GB

Does MRI-GB result in a higher CDR for clinically significant PCa compared with TRUS-GB?

We observed a statistically significant difference between the sensitivity of MRI-GB and TRUS-GB techniques for csPCa, with a pooled relative CDR of 1.24 [95% CI 1.03; 1.50, p = 0.02] although with significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 95.9%) (Fig. 2). The pooled CDR for MRI-GB was 0.83 [95% CI 0.76–0.90] and for TRUS-GB 0.63 [95% CI 0.53–0.74]. Heterogeneity was highly significant––83.7% for MRI-GB and 97.7% for TRUS-GB. We observed no significant evidence of publication bias (p = 0.39, Supplementary Figure 2).

Does MRI-GB result in a lower CDR for insignificant PCa compared with TRUS-GB?

MRI-GB was less likely to result in a diagnosis of clinically insignificant PCa. The diagnostic yield for MRI-GB was 0.08 [95% CI 0.06; 0.11] (I2 = 93.1%) and the yield for TRUS-GB was 0.15 [95% CI 0.12; 0.17] (I2 = 92.7%). The pooled analysis showed that MRI-GB performed significantly better (p < 0.0001) with a pooled relative yield of 0.58 [0.46; 0.74], and moderate heterogeneity between the studies of 63.3% (Fig. 3). There was significant publication bias among the studies (p = 0.003, Supplementary Figure 3).

Which MRI-GB technique performed best at detecting csPCa and avoiding detection of insignificant PCa?

We observed no statistically significant differences between the three MRI-GB techniques in detecting csPCa (p = 0.55) with IB-TB showing a pooled CDR of 0.87 [95% CI 0.81–0.93], COG-TB 0.81 [95% CI 0.69–1.03] and FUS-TB 0.81 [95% CI 0.73-0.91]. There was no statistically significant difference between the three techniques in detecting clinically-insignificant PCa (p = 0.46); IB-TB had a pooled yield of 0.10 [95% CI 0.03–0.31]; COG-TB 0.05 [95% CI 0.02–0.11], and FUS-TB 0.08 [95% CI 0.06–0.11].

Subgroup analysis

Due to the high heterogeneity among the included studies, we performed a subgroup analysis including only studies with low risk of bias and low concerns of applicability (n = 18). This revealed a relative pooled CDR of 1.23 (1.02; 1.47) in the detection of csPCa in favour of MRI-GB (n = 11). The heterogeneity was high (I2 = 90.4%).

The analysis also found the pooled relative CDR in detecting csPCa trended towards higher in patients that had at least one prior negative biopsy (1.59 [95% CI 1.16-2.16]) compared to biopsy-naive men (1.06 [95% CI 0.94–1.20]) although this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.06).

Discussion

In summary, we first found a significant difference in CDR between TRUS-GB and MRI-GB for the detection of csPCa. We also observed considerably higher values of relative CDR after updating the analysis with newly identified studies than those in the previously published systematic review [5]). Third, MRI-GB detected fewer clinically insignificant cancers. Fourth, there was no statistically significant difference between the three techniques in CDR for csPCa.

Whilst the replacement of TRUS-GB with MRI-GB is technically achievable, the removal of systematic biopsy from our diagnostic pathway is controversial. This is due to concerns over missing significant disease ‘hidden’ in areas of the prostate that appear normal on MRI. Indeed, this analysis suggests that whilst superior, an MRI-GB approach alone would miss 17% of cases of csPCa. However, by comparison, TRUS-GB would miss 37% of such cases. This is an expected finding. For example, missing 40% of csPCA is broadly in keeping with the literature [1]. The multicentre PRECISION trial demonstrated the superiority of MRI-GB over TRUS-GB in terms of both detection of csPCa and of overdiagnosis of clinically insignificant PCa [56]. However, some csPCa that is missed by TRUS-GB is detected by MRI-GB and vice versa [57]. A combined approach of both systematic and targeted biopsy may be optimal, although these ‘missed’ cancers are likely to be low volume, low grade or with small amounts of pattern 4, leading to ongoing controversy as to their clinical importance [58].

The debate over which targeting approach is more accurate is ongoing. None of the aforementioned approaches has proven its superiority in a direct comparative trial. In our analysis, we did not find any approach superior in the critical aspect of detecting csPCa. A recently published RCT directly comparing all three approaches found no difference in csPCa detection rates, although the study was powered for the detection of any cancer [59]. The literature may be limited on this topic with highly expert practitioners conducting the COG-TB from which results are reported. Drawing strong conclusions with regard to the presence or absence of superiority of any technique is also challenging due to the significant heterogeneity between included studies. We also found evidence of publication bias in the studies reporting detection rates of csPCa and clinically insignificant disease.

Our meta-analysis has some limitations. First, there was significant patient selection bias in the included studies as in general only men with suspicious MRIs were included. This does not reflect a biopsy-naive population, arguably the most clinically relevant patient group to which this effect applies. If men with non-suspicious MRIs were included, it is likely the effect would be larger [57]. It should therefore be kept in mind that these studies all evaluate the efficacy of an mpMRI scan and a biopsy strategy.

Second, there was significant heterogeneity in the included studies. Some variation was observed in MRI acquisition with variance in scanner resolution, the threshold for biopsy and most importantly, there was inconsistency in the MRI reporting standards. However, all the studies included in the meta-analysis followed the European Society of Genito-Urinary (ESUR) prostate mpMRI guideline standards [7] and 34 of 43 studies used PIRADS as their chosen reporting system. Further, there was variance in the indications for biopsy. As we have already stated, a biopsy-naive population is most relevant and the least biased. We included studies with the multitude of indications that physicians face in clinical practice in order to improve our findings’ generalizability for the reader. Naturally, a more homogeneous group of studies is ideal. However, if only studies with biopsy-naive populations were included only 13 studies with 1878 patients could be included; if only studies using PIRADS with a cutoff score of > /=3 were included in addition to a biopsy-naïve population then only two studies could be included in the meta-analysis.

Third, the thresholds used for csPCa varied although most used the presence of any Gleason >/= 3 + 4 when it was reported. Further, and more problematic, is that commonly used definitions of csPCa are modelled from systematic biopsy data and as such their utility in targeted biopsy has inherent challenges. For example, targeted biopsies by design take multiple cores from a single area of interest. Thus, when total cancer core lengths or numbers/percentages of positive cores are used in this setting there is a significant risk of over-estimation of risk; something we have described as the potential Will–Rogers phenomenon [60].

Fourth, given the aforementioned drawbacks of TRUS-GB [1] we acknowledge that its use as a reference standard for determining the ideal MRI-GB technique is not optimal. Template mapping biopsies would represent a better reference standard for answering our third question. However, one should bear in mind that a recent RCT also found no advantage to any technique [59].

Finally, there were variations in biopsy technique between studies. For example, by the number of cores taken, or whether TRUS-GB or MRI-GB was performed first. If the former is true then prostatic swelling may affect diagnostic accuracy due to the swelling altering prostatic morphology. There are also numerous FUS-TB systems available on the market. Some use rigid fusion systems where the MR-images simply overlay the USS images, and some use elastic fusion systems where double contouring accounts for prostatic deformation by the ultrasound probe. A definitive, multi-user, multi-centre, multi-fusion platform randomized controlled trial sufficiently powered for csPCa to overcome these incorporation biases is needed.

Conclusions

In men where PCa is suspected on MRI, MRI-GB offers superior rates of csPCa detection and significantly reduces diagnoses of insignificant PCa compared to TRUS-GB. In terms of the superiority of MRI-GB techniques we found no significant differences in CDR for csPCa. More than half of the included studies were subject to significant selection bias and thus conclusions must be tempered. Further, in studies reporting on COG-TB, highly expert practitioners performed the biopsies, possibly overstating the sensitivity of the technique. A robust RCT design appropriately powered for csPCa as the primary outcome measure is required to provide a definitive answer.

Code availability

Example r code used for this analysis is found in a statistical methodology paper by Shim et al. [61]

References

Ahmed HU, EL-Shater Bosaily A, Brown LC, Gabe R, Kaplan R, Parmar MK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet. 2017;389:815–22.

European Association of Urology. Guidelines: Prostate Cancer. Available from: https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/?type=summary-of-changes. Accessed 6th May 2020.

Rosenkrantz AB, Hemingway J, Hughes DR, Duszak R Jr, Allen B Jr, Weinreb JC. Evolving use of prebiopsy prostate magnetic resonance imaging in the medicare population. J Urol. 2018;200:89–94.

Liu W, Patil D, Howard DH, Moore RH, Wang H, Sanda MG, et al. Adoption of prebiopsy magnetic resonance imaging for men undergoing prostate biopsy in the united states. Urology. 2018;117:57–63.

Prostate Cancer United Kingdom. mpMRI before biopsy – a step change in prostate cancer diagnosis for men. Available from https://prostatecanceruk.org/about-us/projects-and-policies/mpmri. Accessed 6th September 2020.

Wegelin O, van Melick HHE, Hooft L, Ruud Bosch JLH, Reitsma HB, Barentxz JO, et al. Comparing three different techniques for magnetic resonance imaging-targeted prostate biopsies: a systematic review of in-bore versus magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound fusion versus cognitive regsitration. is there a preferred technique? Eur Urol. 2017;71:517–31.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Barentsz JO, Richenberg J, Clements R, Choyke P, Verma S, Villeirs, et al. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. Eur Radio. 2012;22:746–57.

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(Oct):529–36. 18

Moore CM, Kasivisvanathan V, Eggener S, Emberton M, Fütterer JJ, Gill IS, et al. Standards of reporting for MRI-targeted biopsy studies (START) of the prostate: Recommendations from an international working group. Eur Urol. 2013;64:544–52.

Altman D, Machin D, Bryant TN & Gardner MJ. Statistics with confidence: confidence intervals and statistical guidelines. 2nd ed. BMJ Books; 2000.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Miyagawa T, Ishikawa S, Kimura T, Suetomi T, Tsutsumi M, Irie T, et al. Real-time virtual sonography for navigation during targeted prostate biopsy using magnetic resonance imaging data. Int J Urol. 2010;17:855–60.

Park BK, Park JW, Park SY, Kim CK, Lee HM, Jeon SS, et al. Prospective evaluation of 3-T MRI performed before initial transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy in patients with high prostate-specific antigen and no previous biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:W876–W881.

Portalez D, Mozer P, Cornud F, Renard-Penna R, Misrai V, Thoulouzan M, et al. Validation of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology scoring system for prostate cancer diagnosis on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in a cohort of repeat biopsy patients. Eur Urol. 2012;62:986–96.

Vourganti S, Rastinehad A, Yerram NK, Nix J, Volkin D, Hoang A, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound fusion biopsy detect prostate cancer in patients with prior negative transrectal ultrasound biopsies. J Urol. 2012;188:2152–7.

Delongchamps NB, Peyromaure M, Schull A, Beuvon F, Bouazza N, Flam T, et al. Prebiopsy magnetic resonance imaging and prostate cancer detection comparison of random and targeted biopsies. J Urol. 2013;189:493–9.

Fiard G, Hohn N, Descotes JL, Rambeaud JJ, Troccaz J, Long JA. Targeted MRI-guided prostate biopsies for the detection of prostate cancer: initial clinical experience with real-time 3-dimensional transrectal ultrasound guidance and magnetic resonance/transrectal ultrasound image fusion. Urology. 2013;81:1372–8.

Borkowetz A, Platzek I, Toma M, Laniado M, Baretton G, Froehner M, et al. Comparison of systematic transrectal biopsy to transperineal magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound-fusion biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2015;116:873–9.

Kuru TH, Roethke MC, Seidenader J, Simpfendörfer T, Boxler S, Alammar K, et al. Critical evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging targeted, transrectal ultrasound guided transperineal fusion biopsy for detection of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:1380–6.

Puech P, Rouviere O, Renard-Penna R, Villers A, Devos P, Colombel M, et al. Prostate cancer diagnosis: Multiparametric MR-targeted biopsy with cognitive and transrectal US-MR fusion guidance versus systematic biopsy – prospective multicenter study. Radiology. 2013;268:461–9.

Wysock JS, Rosenkrantz AB, Huang WC, Stifelman MD, Lepor H, Deng FH, et al. A prospective, blinded comparison of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging-ultrasound fusion and visual estimation in the performance of the MR-targeted prostate biopsy: The PROFUS trial. Eur Urol. 2014;66:343–51.

Salami SS, Vira MA, Turkbey B, Fakhoury M, Yaskiv O, Villani R, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging outperforms the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator in predicting clinically significant prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:2876–82.

Iwamoto H, Yumioka T, Yamaguchi N, Inoue S, Masago T, Morizane S, et al. The efficacy of target biopsy of suspected cancer lesions detected by magnetic resonance imaging and/or transrectal ultrasonography during initial prostate biopsies: comparison of outcomes between two physicians. Yonago Acta Med. 2014;57:53–58.

Pokorny MR, de Rooji M, Duncan E, Schröder FH, Parkinson R, Barentsz JO, et al. Prospective study of diagnostic accuracy comparing prostate cancer detection by transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy versus magnetic resonance (MR) imaging with subsequent MR-guided biopsy in men without previous prostate biopsies. Eur Urol. 2014;66:22–29.

Quentin M, Blondin D, Arsov C, Schimmöller L, Hiester A, Godehardt E, et al. Prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging guided in-bore prostate biopsy versus systematic transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy in biopsy naive men with elevated prostate specific antigen. J Urol. 2014;192:1374–9.

Rastinehad AR, Turkbey B, Salami SS, Yaskiv O, George AK, Fakhoury M, et al. Improving detection of clinically significant prostate cancer: magnetic resonance imaging/transrectal ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2014;191:1749–54.

Shakir NA, George AK, Siddiqui M, Rothwax JT, Rais-Bahrami S, Stamatakis L, et al. Identification of threshold prostate specific antigen levels to optimize the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer by magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound fusion guided biopsy. J Urol. 2014;192:1642–8.

Sonn GA, Chang E, Natarajan S, Margolis DJ, Macairan M, Lieu P, et al. Value of targeted prostate biopsy using magnetic resonance-ultrasound fusion in men with prior negative biopsy and elevated prostate-specific antigen. Eur Urol. 2014;65:809–15.

Kaufman S, Kruck S, Kramer U, Gatidis S, Stenzl A, Roethke M, et al. Direct comparison of targeted MRI-guided biopsy with systematic transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy in patients with previous negative prostate biopsies. Urol Int. 2015;94:319–25.

Jambor I, Kähkönen E, Taimen P, Merisaari H, Saunavaara J, Alanen K, et al. Prebiopsy multiparametric 3T prostate MRI in patients with elevated PSA, normal digital rectal examination, and no previous biopsy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41:1394–404.

Boesen L, Noergaard N, Chabanova E, Logager V, Balslev I, Mikines K, et al. Early experience with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for predicting biopsy results in first or repeat biopsy. Scand J Urol. 2015;49:25–34.

Salami SS, Ben-Levi E, Yaskiv O, Tyniker L, Turkbey B, Kavoussi LR, et al. In patients with a previous negative prostate biopsy and a suspicious lesion on magnetic resonance imaging, is a 12-core biopsy still necessary in addition to a targeted biopsy? BJU Int. 2015;115:562–70.

Shoji S, Hiraiwa S, Endo J, Hashida K, Tomonage T, Nakano M, et al. Manually controlled targeted prostate biopsy with real-time fusion imaging of multiparametric resonance imaging and transrectal ultrasound: an early experience. Int J Urol. 2015;22:173–8.

Mozer P, Rouprêt M, Le Cossec C, Granger B, Comperat E, de Gorski A, et al. First round of targeted biopsies using magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasonography fusion compared with conventional transrectal ultrasonography-guided biopsies for the diagnosis of localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2015;115:50–57.

Pepe P, Garufi A, Priolo G, Pennisi M. Can 3-Tesla pelvic phased-array multiparametric MRI avoid unnecessary repeat prostate biopsy in patients with PSA <10 ng/mL? Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13:e27–e30.

Arsov C, Rabenalt R, Blondin D, Quentin M, Hiester A, Godehardt E, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided in-bore biopsy to MRI-ultrasound fusion and transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy in patients with prior negative biopsies. Eur Urol. 2015;68:713–20.

Cash H, Maxeiner A, Stephan C, Fischer T, Durmus T, Holzmann J, et al. The detection of significant prostate cancer is correlated with the Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) in MRI/transrectal ultrasound fusion biopsy. World J Urol. 2016;34:525–32.

Mariotti GC, Costa DN, Pedrosa I, Falsarella PM, Martins T, Roehrborn CG, et al. Magnetic resonance/transrectal ultrasound fusion biopsy of the prostate compared to systematic 12-core biopsy for the diagnosis and characterization of the prostate cancer: multi-institutional retrospective analysis of 389 patients. Urol Oncol. 2016;34:416.e9–416.e14.

Cool DW, Romagnoli C, Izawa JI, Chin J, Gardi L, Tessier D, et al. Comparison of prostate MRI-3D transrectal ultrasound fusion biopsy for first-time and repeat biopsy patients with previous atypical small acinar proliferation. Can Urol Assoc J. 2016;10:342–8.

Boesen L, Nørgaard N, Løgager V, Balslev I, Thomsen HS. A Prospective Comparison of Selective Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging Fusion-Targeted and Systematic Transrectal Ultrasound-Guided Biopsies for Detecting Prostate Cancer in Men Undergoing Repeated Biopsies. Urol Int. 2017;99:384–91.

Garcia Bennett J, Vilanova JC, Gumà Padró J, Parada D, Conejero A. Evaluation of MR imaging-targeted biopsies of the prostate in biopsy-naïve patients. A single centre study. Diagn Inter Imaging. 2017;98:677–84.

Borkowetz A, Hadaschik B, Platzek I, Toma M, Torsev G, Renner T, et al. Prospective comparison of transperineal magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasonography fusion biopsy and transrectal systematic biopsy in biopsy-naïve patients. BJU Int. 2018;121:53–60.

Bladou F, Fogaing C, Levental M, Aronson S, Alameldin M, Anidjar M. Transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy for prostate cancer detection: systematic and-or magnetic-resonance imaging-targeted. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11:E330–E337.

Jelidi A, Ohana M, Labani A, Alemann G, Lang H, Roy C. Prostate cancer diagnosis: efficacy of a simple electromagnetic MRI-TRUS fusion method to target biopsies. Eur J Radio. 2017;86:127–34.

Sidana A, Watson MJ, George AK, Rastinehad AR, Vourganti S, Rais-Bahrami S, et al. Fusion prostate biopsy outperforms 12-core systematic prostate biopsy in patients with prior negative systematic biopsy: A multi-institutional analysis. Urol Oncol. 2018;36:341.e1–341.e7.

Mortezavi A, Märzendorfer O, Donati OF, Rizzi G, Rupp NJ, Wettstein MS, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multiparametric resonance imaging and fusion guided targeted biopsy evaluated by transperineal template saturation prostate biopsy for the detection and characterization of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2018;200:309–18.

Fourcade A, Payrard C, Tissot V, Perrouin-Verbe MA, Demany N, Serey-Effeil S, et al. The combination of targeted and systematic prostate biopsies is the best protocol for the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer. Scand J Urol. 2018;52:174–9.

Sönmez G, Tombul ST, İmamoğlu H, Akgün H, Demirtaş A, Tatlışen A. Multiparametric MRI fusion-guided prostate biopsy in biopsy naïve patients: Preliminary results from 80 patients. Turk J Urol. 2019;45:196–201.

Hwang SI, Lee HJ, Lee SE, Hong SK, Byun SS, Lee SC, et al. Value of MR-US fusion in guidance of repeated prostate biopsy in men with PSA<10ng/mL. Clin Imaging. 2019;53:1–5.

Exterkate L, Wegelin O, Barentsz JO, van der Leest MG, Kummer JA, Vreuls W. Is there still a need for repeated systematic biopsies in patients with previous negative biopsies in the era of magnetic resonance imaging-targeted biopsies of the prostate? Eur Urol Oncol. 2020;3:216–23.

Van der Leest M, Cornel E, Israël B, Hendricks R, Padhani AR, Hoogenboom M, et al. Head-to-head comparison of transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy versus multiparametric prostate resonance imaging with subsequent magnetic resonance-guided biopsy in biopsy-naïve men with elevated prostate-specific antigen: a large prospective multicenter clinical study. Eur Urol. 2019;75:570–8.

D’Agostino D, Mineo Bianchi F, Romagnoli D, Corsi P, Giampaoli M, Schiavina R et al. Comparison between “In-bore” MRI guided prostate biopsy and standard ultrasound guided biopsy in the patient with suspicious prostate cancer: Preliminary results. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2019;91:4.

Kaushal R, Das CJ, Singh P, Dogra PN, Jumar R. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound fusion biopsies increase the rate of cancer detection in populations with a low incidence of prostate cancer. Investig Clin Urol. 2019;60:156–61.

Mannaerts CK, Kajtazovic A, Lodeizen OAP, Gayet M, Engelbrecht MRW, Jager GJ, et al. The added value of systematic biopsy in men with suspicion of prostate cancer undergoing multiparametric MRI-targeted biopsy. Urol Oncol. 2019;37:298.e1–298.e9.

Kasivisvanathan V, Rannikko AS, Borghi M, Panebianco V, Mynderse LA, Vaarala MH, et al. MRI-targeted or standard biopsy for prostate-cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1767–77.

Elkhhoury FF, Felker ER, Kwan L, Sisk AE, Delfin M, Natarajan S, et al. Comparison of targeted vs systematic prostate biopsy in men who are biopsy naïve. the prospective assessment of image registration in the diagnosis of the prostate cancer (PAIREDCAP) study. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:811–8.

Ahdoot M, Wilbut AR, Reese SE, Lebastchi AH, Mehralivand S, Gomella PT, et al. MRI-targeted, systematic, and combined biopsy for prostate cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:917–28.

Wegelin O, Exterkate L, van der Leest M, Kummer JA, Vreuls W, de Bruin PC, et al. The FUTURE Trial: a multicenter randomised controlled trial on target biopsy technique based on magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of prostate cancer in patients with prior negative biopsies. Eur Urol. 2019;75:582–90.

Bass EJ, Orczyk C, Grey A, Freeman A, Jameson C, Punwani S et al. Targeted biopsy of the prostate: does this results in improvement in detection of high-grade cancer or the occurrence of the Will Rogers phenomenon? BJU Int. 2019 May 13 https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14806. [Epub ahead of print]

Shim S, Kim SJ, Lee J. Diagnostic test accuracy: application and practice using R software. Epidemiol Health. 2019;41:e2019007.

Funding

HA is supported by the Wellcome Trust via a Senior Clinical Research Fellowship. Grant code: 204998/Z/16/Z.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization HUA; data collection HUA, AP; Statistical analysis AP; writing-original draft preparation EJB; writing-review and editing MC, SL, AR, MW, RG; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

HUA’s research is supported by core funding from the United Kingdom’s National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. HUA currently receives funding from the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council (UK), Cancer Research UK, Prostate Cancer UK, The Urology Foundation, BMA Foundation, Imperial Health Charity, NIHR Imperial BRC, Sonacare Inc., Trod Medical and Sophiris Biocorp for trials in prostate cancer. HUA was a paid medical consultant for Sophiris Biocorp in the previous 3 years. HUA receives fees for proctoring in cryotherapy (Boston), Rezum (Boston) and HIFU (Sonacare Inc). SL is supported by the Prostate Cancer Foundation. RA receives research support from Philips Healthcare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bass, E.J., Pantovic, A., Connor, M.J. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging targeted biopsy techniques compared to transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy of the prostate: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 25, 174–179 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-021-00449-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-021-00449-7

This article is cited by

-

Prostate cancer detection and complications of MRI-targeted prostate biopsy using cognitive registration, software-assisted image fusion or in-bore guidance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2024)

-

Clinical and economic impact of the introduction of pre-biopsy MRI-based assessment on a large prostate cancer centre diagnostic population and activity: 10 years on

World Journal of Urology (2024)

-

Automated prostate gland segmentation in challenging clinical cases: comparison of three artificial intelligence methods

Abdominal Radiology (2024)

-

Development of a novel nomogram to identify the candidate to extended pelvic lymph node dissection in patients who underwent mpMRI and target biopsy only

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2023)

-

Landmarks in the evolution of prostate biopsy

Nature Reviews Urology (2023)