Abstract

Background

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) surveillance testing is a cornerstone of prostate cancer survivorship because patients with biochemical recurrence often have no symptoms. However, the investigation of guideline-concordant PSA surveillance across racial groups is limited. We examined racial differences in PSA surveillance testing 5-years post-definitive treatment for localized prostate cancer.

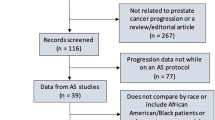

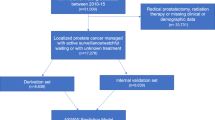

Methods

We created a population-based retrospective cohort from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare linked database for men diagnosed with prostate cancer between the years 2007 to 2011 with Medicare claims through 2016 (N = 21,372). Multivariable log-binomial regression models were used to examine the effect of race on the likelihood of not receiving at least one PSA surveillance test annually 5-years post-definitive treatment.

Results

Black men had 90%, 71%, 44%, 34%, and 23% increased risk of not receiving at least one PSA surveillance test annually in the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth years of post-definitive treatment follow-up, respectively. The adjusted relative risk [ARR] for Black men compared to White men were 1.68 (95% Confidence Interval [CI], 1.37–2.07), 1.52 (95% CI, 1.32–1.75), 1.32 (95% CI, 1.17–1.48), and 1.16 (95% CI, 1.05–1.29) in the first, second, third, and fourth year of post-definitive treatment, respectively.

Conclusion

Black men were more likely not to receive guideline-concordant PSA surveillance testing following definitive treatment for localized prostate cancer during the first 4 years post-treatment. This study suggest room for improvement in defining survivorship care plans for Black men to increase use of PSA surveillance testing.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 4 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $64.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2020. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2020.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2016-8. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. 2016.

Chen RC, Rumble RB, Jain S. Active surveillance for the management of localized prostate cancer (Cancer Care Ontario guideline): American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement Summary. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:267–9.

Godley PA, Schenck AP, Amamoo MA, Schoenbach VJ, Peacock S, Manning M, et al. Racial differences in mortality among Medicare recipients after treatment for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1702–10.

Carpenter WR, Howard DL, Taylor YJ, Ross LE, Wobker SE, Godley PA. Racial differences in PSA screening interval and stage at diagnosis. Cancer Causes Control CCC. 2010;21:1071–80.

Cobran EK, Chen RC, Overman R, Meyer AM, Kuo TM, O’Brien J, et al. Racial differences in diffusion of intensity-modulated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Am J Men Health. 2016;10:399–407.

Ciezki JP, Reddy CA, Stephenson AJ, Angermeier K, Ulchaker J, Altman A, et al. The importance of serum prostate-specific antigen testing frequency in assessing biochemical and clinical failure after prostate cancer treatment. Urology. 2010;75:467–71.

Trantham LC, Nielsen ME, Mobley LR, Wheeler SB, Carpenter WR, Biddle AK. Use of prostate‐specific antigen testing as a disease surveillance tool following radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2013;119:3523–30.

Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, Chan DW, Pearson JD, Walsh PC. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA 1999;281:1591–7.

Jemal A, Ward E, Wu X, Martin HJ, McLaughlin CC, Thun MJ. Geographic patterns of prostate cancer mortality and variations in access to medical care in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2005;14:590–5.

Mohler JL. The 2010 NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology on prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:145.

Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Medical Care. 2002;40:Iv-3-18.

National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) overview fact sheets. Rockville, MD: NCI; 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/about/factsheets/SEER_Overview.pdf.

Koroukian SM, Dahman B, Copeland G, Bradley CJ. The utility of the state buy-in variable in the Medicare denominator file to identify dually eligible Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries: a validation study. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:265–82.

Koroukian SM, Xu F, Dor A, Cooper GS. Colorectal cancer screening in the elderly population: disparities by dual Medicare-Medicaid enrollment status. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:2136–54.

O’Leary JE, Sloss EM, Melnick G. Disabled Medicare beneficiaries by dual eligible status: California, 1996–2001. Health Care Financing Rev. 2007;28:57–67.

Stokes WA, Hendrix LH, Royce TJ, Allen IM, Godley PA, Wang AZ, et al. Racial differences in time from prostate cancer diagnosis to treatment initiation: a population-based study. Cancer. 2013;119:2486–93.

D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, Schultz D, Blank K, Broderick GA, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 1998;280:969–74.

Matsumoto K, Niwa N, Hattori S, Takeda T, Morita S, Kosaka T, et al. Establishment of the optimal follow-up schedule after radical prostatectomy. Urologic Oncol. 2018;36:341.e9–.e14.

Dess RT, Hartman HE, Mahal BA, Soni PD, Jackson WC, Cooperberg MR, et al. Association of black race with prostate cancer–specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:975–83.

Paller CJ, Wang L, Brawley OW. Racial inequality in prostate cancer outcomes—socioeconomics. Not Biol JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:983–4.

Johnson TJ, Weaver MD, Borrero S, Davis EM, Myaskovsky L, Zuckerbraun NS, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with management of abdominal pain in the emergency department. Pediatrics 2013;132:e851–8.

Venkat A, Hoekstra J, Lindsell C, Prall D, Hollander JE, Pollack CV Jr., et al. The impact of race on the acute management of chest pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1199–208.

Weisse CS, Sorum PC, Dominguez RE. The influence of gender and race on physicians’ pain management decisions. J Pain. 2003;4:505–10.

Weisse CS, Sorum PC, Sanders KN, Syat BL. Do gender and race affect decisions about pain management? J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:211–7.

Armstrong K, McMurphy S, Dean LT, Micco E, Putt M, Halbert CH, et al. Differences in the patterns of health care system distrust between blacks and whites. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:827–33.

Armstrong K, Ravenell KL, McMurphy S, Putt M. Racial/ethnic differences in physician distrust in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1283–9.

Davis JL, Bynum SA, Katz RV, Buchanan K, Green BL. Sociodemographic differences in fears and mistrust contributing to unwillingness to participate in cancer screenings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:67–76.

Myers RE, Chodak GW, Wolf TA, Burgh DY, McGrory GT, Marcus SM, et al. Adherence by African American men to prostate cancer education and early detection. Cancer: Interdisciplinary. Int J Am Cancer Soc. 1999;86:88–104.

Wen W, Luckenbaugh AN, Bayley CE, Penson DF, Shu XO. Racial disparities in mortality for patients with prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33152. [Eub ahead of print].

Wang EH, Yu JB, Abouassally R, Meropol NJ, Cooper G, Shah ND, et al. Disparities in treatment of patients with high-risk prostate cancer: results from a population-based cohort. Urology. 2016;95:88–94.

Welch HG, Fisher ES, Gottlieb DJ, Barry MJ. Detection of prostate cancer via biopsy in the Medicare-SEER population during the PSA era. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1395–400.

Jones BA, Liu WL, Araujo AB, Kasl SV, Silvera SN, Soler-Vila H, et al. Explaining the race difference in prostate cancer stage at diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17:2825–34.

Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Ziehr DR, Hyatt AS, Sammon JD, Schmid M, et al. Trends in disparate treatment of African American men with localized prostate cancer across National Comprehensive Cancer Network risk groups. Urology. 2014;84:386–92.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant 1K01CA230193-01A1, National Institute of Health KL2 Scholars Grant KL2TR00238, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences UL1 Diversity Supplement Grant 3UL1TR002378-02S2, and Institutional Research Grant-14-193-01 from the American Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IMA: Conceptualization, formal analysis, software, and writing – review and editing. RCC: Formal analysis, software, and writing – review and editing. HNY: Conceptualization, formal analysis, software, and writing– review and editing. JC: Methodology, project administration, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. AM: Formal analysis, and writing– review and editing. SRHB: Conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing– review and editing. VM: Formal analysis, writing– review and editing. JR-T: Formal analysis, writing– review and editing. EKC: Conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, software, and writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asiri, I.M., Chen, R.C., Young, H.N. et al. Race and prostate specific antigen surveillance testing and monitoring 5-years after definitive therapy for localized prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 24, 1093–1102 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-021-00365-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-021-00365-w

This article is cited by

-

Disparities in prostate cancer diagnosis and management: recognizing that disparities exist at all junctures along the prostate cancer journey

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2023)