Abstract

Background

Deciding when to biopsy a man with non-suspicious DRE findings and tPSA in the 4–10 ng/ml range can be challenging, because two-thirds of such biopsies are typically found to be benign. The Prostate Health Index (phi) exhibits significantly improved diagnostic accuracy for prostate cancer detection when compared to tPSA and %fPSA, however only one published study to date has investigated its impact on biopsy decisions in clinical practice.

Methods

An IRB approved observational study was conducted at four large urology group practices using a physician reported two-part questionnaire. Physician recommendations were recorded before and after receiving the phi test result. A historical control group was queried from each site's electronic medical records for eligible men who were seen by the same participating urologists prior to the implementation of the phi test in their practice. 506 men receiving a phi test were prospectively enrolled and 683 men were identified for the historical control group (without phi). Biopsy and pathological findings were also recorded for both groups.

Results

Men receiving a phi test showed a significant reduction in biopsy procedures performed when compared to the historical control group (36.4% vs. 60.3%, respectively, P < 0.0001). Based on questionnaire responses, the phi score impacted the physician’s patient management plan in 73% of cases, including biopsy deferrals when the phi score was low, and decisions to perform biopsies when the phi score indicated an intermediate or high probability of prostate cancer (phi ≥36).

Conclusions

phi testing significantly impacted the physician’s biopsy decision for men with tPSA in the 4–10 ng/ml range and non-suspicious DRE findings. Appropriate utilization of phi resulted in a significant reduction in biopsy procedures performed compared to historical patients seen by the same participating urologists who would have met enrollment eligibility but did not receive a phi test.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for prostate cancer (PCa) has come under increasing scrutiny in recent years. Despite a documented reduction in men presenting with metastatic disease since PSA was first introduced in the early 1990s [1, 2], its debatable impact on overall survival and an increasing concern about over-diagnosis of indolent cancer has led to restricted recommendations regarding its use [3,4,5]. The US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against PSA screening for men of any age in 2012 [6], although an updated draft recommendation statement was recently issued for public comment, wherein the USPSTF acknowledged that PSA testing may be appropriate for certain men in the 55–69 year age range (C-recommendation) [7].

Another problem associated with PSA testing is its relatively poor diagnostic specificity. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), ~85% of men with PSA levels <4 ng/ml are found to have non-cancerous biopsy findings, whereas men with PSA levels between 4–10 ng/ml have ~30–35% chance of a positive biopsy result [8]. This potentially exposes over two-thirds of such men to complications associated with prostate biopsies such as bleeding, pain, and the risk of infection. Given these limitations, there is considerable interest in new biomarker panels demonstrating improved clinical specificity for PCa detection.

The Beckman Coulter Prostate Health Index (phi) combines the results of three quantitative kallikrein immunoassays, total PSA (tPSA), free PSA (fPSA), and [-2]proPSA (p2PSA) into a single numerical score (the phi score): (p2PSA/fPSA × √tPSA). It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 for use as an aid in distinguishing PCa from other benign prostatic conditions in men aged 50 years having non-suspicious digital rectal exam (DRE) findings and with serum tPSA levels ranging from 4 to 10 ng/ml [9]. The pivotal clinical trial submitted for FDA approval included 658 men who met the above criteria and ranged in age from 50 to 84 years. The phi test showed a significant improvement in PCa detection when compared with tPSA and %fPSA. For example, a phi score of 27.0 provided 31.1% clinical specificity at a sensitivity cutoff of 90%. This represented nearly a 3-fold improvement in PCa detection compared with tPSA testing alone.

An expanded version of the multicenter study described above was published, including 892 men with serum tPSA levels ranging from 2 to 10 ng/ml [10]. An increasing phi score was associated with a 4.7-fold increased risk of prostate cancer and a 1.61-fold increased risk of aggressive cancer (Gleason score ≥7) on biopsy. Additionally, the improved diagnostic performance of phi has been demonstrated in numerous other published clinical studies world-wide [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. A meta-analysis from eight such studies [27], representing 2919 patients in total, showed a pooled clinical specificity of 31.6% at the 90% sensitivity threshold (95% Cl, 29.2%–34.0%).

Despite the proven diagnostic performance of phi, only one published study to date has evaluated its clinical utility in real world practice [28]. The purpose of the current study was to prospectively examine the impact of phi testing on biopsy decisions in four large urology group practices. The primary objective was to examine how phi influenced the physician’s management plan using a two-part questionnaire. The secondary objective was to compare biopsy procedures performed for patients receiving a phi test to historical controls seen by the same participating physicians before the phi test had been implemented in their practice.

Materials and Methods

Sites were selected based on the commercial implementation of phi into their practice. Four large urology group practices agreed to participate in the study, representing geographically diverse regions across the United States. The protocol was approved by a central institutional review board (IRB) with waived consent because all patient information was de-identified. Men receiving a phi test result were prospectively enrolled from July 2015 through April 2017. Historical control patients were identified from each site within 24 months prior to initiating the study protocol.

Study design

This was a prospective, observational study to determine if the use of phi testing changes physician behavior patterns when comparing their biopsy recommendations to a historical control group of similar patients seen by the same physicians (Fig. 1). A two-part questionnaire was used to document the physician’s preliminary patient management plan before receiving the phi result, compared to their final recommendation for that same patient after receiving the phi result (Fig. 2). Questions included whether or not knowledge of the phi result was helpful when communicating their final recommendation to patients. Clinical and pathological data for both patient groups was extracted from on-site electronic medical records.

Subjects

Patients for whom a participating urologist requested a phi test were recruited at the time of blood draw for the prospective (observational) study group. Inclusion criteria: men ≥50 years of age with total serum PSA between 4–10 ng/ml and non-suspicious DRE findings. The prior PSA test was required to be performed within 6 months of the DRE. Exclusion criteria: men with a prior history of PCa, use of any dosage of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors within the previous 3 months, men with a previous biopsy result that was either positive or suspicious for prostate cancer (e.g., HGPIN, atypia), men with a history of prostatectomy for any reason, or men who had undergone transurethral resection of the prostate. Patients were also excluded if the physician decided not to wait for the phi result before performing a biopsy.

The historical cohort of patients was selected from each site’s electronic medical records for the purpose of establishing a baseline of practice patterns within the 24 months prior to their initiating the study protocol. Patients included in this group met the inclusion/exclusion criteria but did not receive a phi test as part of their assessment. For inclusion in the historical control group, patients had to be treated by the same physicians participating in the prospective arm of the study.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint of phi impact on decision to biopsy was assessed for statistical significance using the Normal Approximation to the binomial test for proportions. Percentages for categorical responses from the two-part questionnaire were calculated from Total N or available data (where applicable). All data reporting and analyses were done using SAS Software version 9.4M3. All statistical tests were conducted with ɑ = 0.05, unless otherwise stated.

Results

Our study comprised a total of 506 men in the prospective arm and 683 men in the historical control arm (Table 1). Patient age distributions, demographics, and clinical risk factors were balanced between the two arms.

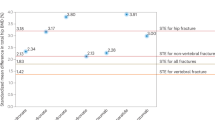

Table 2 summarizes the frequency of biopsy procedures performed between the prospective and historical control groups. 36.4% of men in the prospective group received a biopsy (95% CI, 32.5%–40.9%), compared to the non-phi tested historical control group’s biopsy rate of 60.3% (95% CI, 56.3%–63.9%). This demonstrated a statistically significant reduction (P < 0.0001) in biopsy procedures for patients receiving a phi test result. In the prospective arm, 147 of 162 men (90.7%) were undergoing their first biopsy (22 of 184 men did not have a biopsy history reported), and in the historical arm, 339 of 355 men (95.5%) were undergoing their first biopsy (57 of 412 men did not have a biopsy history reported). The proportion of positive biopsy findings did not increase in the prospective group, while there was a modest decrease in the overall percentage of low-grade Gleason 6 tumors detected compared to the historical control group (9.9% vs. 18.4%, respectively).

Table 3 summarizes the physician-reported decision impact of the phi test result on their patient management plan, based on their Pre-Test vs. Post-Test Questionnaire responses. Overall, 72.5% of the physician responses indicated that the phi score did impact their patient management plan after accounting for other clinical factors. This included 43% of cases where the physician reported a changed biopsy recommendation based on the phi result, and 19% of cases where the preliminary monitoring strategy was modified based on the phi result (i.e., more or less frequent follow-up and/or inclusion of additional testing such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)). Additionally, 92% of physician responses indicated that knowledge of the phi score was helpful when communicating their recommendation to the patient, including 28% of cases where a “reduced risk” phi score was helpful in alleviating the patient’s anxiety about the likelihood of significant cancer.

Discussion

This large study represents the only multicenter study to date investigating the impact of phi testing on biopsy decisions for patients presenting with elevated serum PSA and non-suspicious DRE findings. Our study compared a prospective group of patients assessed with phi to a non-phi historical cohort evaluated by the same participating physicians within the previous 24 months. Physicians were more inclined to defer biopsy when phi testing was included in their overall assessment, resulting in a net 24% reduction in biopsies performed compared to the historical control group. In addition, we observed an overall reduction in the percentage of low-grade Gleason score 6 tumors detected with phi.

Most recently, Tosoian et al. [28] reported similar findings with phi testing in their large academic center practice at Johns Hopkins University. A prospective registry of 345 men receiving a phi result was compared to a contemporary cohort of 1318 men who did not undergo phi testing. Their comparative analysis showed that phi testing reduced the rate of biopsy procedures performed without changing the frequency of higher-grade cancers detected. Overall, 39% of men in their registry underwent a biopsy when phi was included in the assessment, representing a 9% reduction in the rate of prostate biopsy procedures performed compared to the control group (48%, P < 0.001). 91% of men with phi <27 who underwent a biopsy had either a non-cancerous result or low-grade (Gleason score 6) pathology, whereas 76% of men with phi >55 had Gleason score ≥7 cancers. For men receiving an MRI as part of their assessment, the phi score was also shown to provide complimentary information for ruling out significant prostate cancer.

The two-part questionnaire used in our study was helpful for elucidating how knowledge of the phi result impacted the physician’s management decision to perform a biopsy or monitor the patient. According to the responses, physicians were less inclined to biopsy patients receiving a low phi score, and more inclined to recommend biopsy for patients receiving an intermediate to high-risk phi score (phi ≥36). phi also improved the physician’s ability to communicate their recommendation to the patient, and helped alleviate patient anxiety in cases where the phi score was low.

Although our study was not sufficiently powered to demonstrate differences in pathological staging, a number of published studies have shown that elevated phi scores can predict higher-grade prostate cancers (Gleason score ≥7) [26, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. The predictive accuracy can vary depending on the patient cohort investigated, however. For example, a recently published review reported AUC values ranging from 0.707 to 0.82 [37]. The lowest AUC value excluded men with suspicious DRE findings [29], whereas the highest AUC value included 23.7% of men who reportedly had an abnormal DRE [34]. In all cases, phi predicted aggressive prostate cancer with AUC values that were significantly greater than those for %fPSA or tPSA.

As previously reported in simulated budget impact studies [38, 39], the addition of phi testing represents a cost-effective strategy for prostate cancer detection while avoiding unnecessary biopsies. The present study demonstrates this benefit in real world clinical practice.

Our study included four large urology group practices representing diverse regions across the United States. One strength of our study was the enrollment of patients seen by the same participating physicians for the prospective and historical control groups. Weaknesses include no use of randomization and lack of longitudinal follow-up. These were not utilized since our study was intended to be strictly observational and was designed to measure decision impact at the point of the urologist consultation. Further studies are needed to address questions of long-term patient outcomes from subsequent biopsy procedures and later episodes of care.

Conclusions

This represents the largest prospective study to date investigating the clinical utility of phi testing for men undergoing a diagnostic assessment for PCa. Overall, phi impacted the physician’s patient management decision in 73% of observational cases. Fewer men were biopsied when phi testing was included in the assessment (36% vs. 60% historically), along with an overall reduction in the percentage of low-grade Gleason score 6 cancers detected. Our results show that appropriate utilization of phi can significantly modify physician behavior patterns and improve their ability to diagnose and manage their patients. We believe our study supports the routine use of phi testing for men presenting with elevated serum total PSA and non-suspicious DRE findings.

References

Cooperberg MR, Moul JW, Carroll PR. The changing face of prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8146–51

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & Figures. 2014. (http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/webcontent/acspc-042151.pdf.)

Brett AS, Ablin RJ. Prostate-Cancer Screening - what the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force left out. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1949–51.

Kim EH, Andriole GL. Prostate-specific antigen-based screening: controversy and guidelines. BMG Med. 2015;13:61–65.

Hayes JH, Barry MJ. Screening for prostate cancer with the Prostate-Specific Antigen Test. JAMA. 2014;311:1143–9.

Moyer VA. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:120–34.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ. The US Preventative Services 2017 draft recommendation statement on screening for prostate cancer – an invitation to review and comment. JAMA. 2017;317:1949–50.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer Early Detection. Version 2. 2016. (https://www.nccn.org/ professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate_detection.pdf).

FDA Premarket Approval Application (PMA) Number: P090026. (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf9/P090026b.pdf).

Catalona W, Partin A, Sanda M, Wei JT, Klee GG, Bangma CH, et al. A multi-center study of [−2]pro-prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in combination with PSA and free PSA for prostate cancer detection in the 2.0 to 10.0 ng/mL PSA range. J Urol. 2011;185:1650–5.

Lazzeri M, Lughezzani G, Haese A, McNicholas T, de la Taille A, Buffi NM, et al. Clinical performance of prostate health index in men with tPSA>10 ng/ml: results from a multi-centric European study. Urol Oncol. 2016;34:415e13–415e19.

Gnanapragasam VJ, Burling K, George A, Stearn S, Warren A, Barrett T, et al. The prostate health index adds predictive value to multi-parametric MRI in detecting significant prostate cancers in a repeat biopsy population. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35364.

Abrate A, Lazzeri M, Lughezzani G, Buffi N, Bini V, Haese A, et al. Clinical performance of the Prostate Health Index (PHI) for the prediction of prostate cancer in obese men: data from the PROMEtheuS project, a multicentre European prospective study. BJU Int. 2015;115:537–45.

Fossati N, Lazzeri M, Haese A, McNicholas T, de la Taille A, Buffi NM, et al. Clinical performance of serum isoform [-2]proPSA (p2PSA), and its derivatives %p2PSA and the Prostate Health Index, in men aged<60 years: results from a multicentric European study. BJU Int. 2015;115:913–20.

Filella X, Foj L, Augé JM, Molina R, Alcover J. Clinical utility of %p2PSA and prostate health index in the detection of prostate cancer. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52:1347–55.

Lazzeri M, Abrate A, Lughezzani G, Gadda GM, Freschi M, Mistretta F, et al. Relationship of chronic histologic prostatic inflammation in biopsy specimens with serum isoform [-2]proPSA (p2PSA), %p2PSA, and prostate health index in men with a total prostate-specific antigen of 4-10 ng/ml and normal digital rectal examination. Urology. 2014;83:606–12.

Filella X, Foj L, Alcover J, Augé JM, Molina R, Jiménez W. The influence of prostate volume in prostate health index performance in patients with total PSA lower than 10 μg/L. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;436:303–7.

Wang W, Wang M, Wang L, Adams TS, Tian Y, Xu J. Diagnostic ability of %p2PSA and prostate health index for aggressive prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:1–8.

Stephan C, Vincendeau S, Houlgatte A, Cammann H, Jung K, Semjonow A. Multicenter evaluation of [-2]proprostate-specific antigen and the prostate health index for detecting prostate cancer. Clin Chem. 2013;59:306–14.

Lazzeri M, Haese A, de la Taille A, Palou Redorta J, McNicholas T, Lughezzani G, et al. Serum isoform [-2]proPSA derivatives significantly improve prediction of prostate cancer at initial biopsy in a total PSA range of 2-10 ng/ml: a multicentric European study. Eur Urol. 2013;63:986–94.

Lazzeri M, Haese A, Abrate A, de la Taille A, Redorta JP, McNicholas T, et al. Clinical performance of serum prostate-specific antigen isoform [-2]proPSA (p2PSA) and its derivatives, %p2PSA and the prostate health index (PHI), in men with a family history of prostate cancer: results from a multicentre European study, the PROMEtheuS project. BJU Int. 2013;112:313–21.

Lazzeri M, Briganti A, Scattoni V, Lughezzani G, Larcher A, Gadda G, et al. Serum index test %[-2]proPSA and prostate health index are more accurate than prostate specific antigen and %fPSA in predicting a positive repeat prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2012;188:1137–43.

Guazzoni G, Nava L, Lazzeri M, Scattoni V, Lughezzani G, Maccagnano C, et al. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) isoform p2PSA significantly improves the prediction of prostate cancer at initial extended prostate biopsies in patients with total PSA between 2.0 and 10 ng/mL: results of a prospective study in a clinical setting. Eur Urol. 2011;60:214–22.

Jansen F, van Schaik R, Kurstjens J, Horninger W, Klocker H, Bektic J, et al. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) isoform p2PSA in combination with total PSA and free PSA improves diagnostic accuracy in prostate cancer detection. Eur Urol. 2010;57:921–7.

Le B, Griffin C, Loeb S, Carvalhal G, Kan D, Baumann N, et al. [-2]Proenzyme prostate specific antigen is more accurate than total and free prostate specific antigen in differentiating prostate cancer from benign disease in a prospective prostate cancer screening study. J Urol. 2010;183:1355–9.

Sokoll LJ, Sanda MG, Feng Z, Kagan J, Mizrahi IA, Broyles DL, et al. A prospective, multicenter, national cancer institute early detection research network study of [-2]proPSA: improving prostate cancer detection and correlating with cancer aggressiveness. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1193–1200.

Filella X, Giménez N. Evaluation of [-2] proPSA and Prostate Health Index (phi) for the detection of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51:729–39.

Tosoian JJ, Druskin SC, Andreas D, Mullane P, Chappidi M, Joo S, et al. Use of the Prostate Health Index for detection of prostate cancer: results from a large academic practice. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017;20:228–33.

Loeb S, Shin SS, Broyles DL, Wei JT, Sanda M, Klee G, et al. Prostate Health Index improves multivariable risk prediction of aggressive prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2016;120:61–68

Boegemann M, Stephan C, Cammann H, Vincendeau S, Houlgatte A, Jung K, et al. The percentage of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) isoform [-2]proPSA and the Prostate Health Index improve the diagnostic accuracy for clinically relevant prostate cancer at initial and repeat biopsy compared with total PSA and percentage free PSA in men aged≤65 years. BJU Int. 2016;117:72–9.

Veltri RW. Serum marker %[-2]pro-PSA and the prostate health index improve diagnostic accuracy for clinically relevant prostate cancer. BJU int. 2016;117:12–3.

Schwen ZR, Tosoian JJ, Sokoll LJ, Mangold L, Humphreys E, Schaeffer EM, et al. Prostate Health Index (PHI) predicts high-stage pathology in African American men. Urology. 2016;90:136–40.

Loeb S, Sanda MG, Broyles DL, Shin SS, Bangma CH, Wei JT, et al. The prostate health index selectively identifies clinically significant prostate cancer. J Urol. 2015;193:1163–9.

de la Calle C, Patil D, Wei JT, Scherr DS, Sokoll L, Chan DW, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the prostate health index to detect aggressive prostate cancer in biopsy naïve men. J Urol. 2015;194:65–72.

Wang W, Wang M, Wang L, Adams TS, Tian Y, Xu J. Diagnostic ability of %p2PSA and prostate health index for aggressive prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5012.

Heidegger H, Klocker H, Steiner E, Skradski V, Ladurner M, Pichler R, et al. [-2]proPSA is an early marker for prostate cancer aggressiveness. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17:70–74.

Lepor A, Catalona W, Loeb S. The Prostate Health Index: its utility in prostate cancer detection. Urol Clin North Am. 2016;43:1–6.

Nichol M, Wu J, Huang J, Denham D, Frencher S, Jacobsen S. Budget impact analysis of a new prostate cancer risk index for prostate cancer detection. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:253–61.

Nichol M, Wu J, Huang J, Denham D, Frencher S, Jacobsen S. Cost effectiveness of prostate health index for prostate cancer detection. BJU Int. 2011;110:353–62.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by funding from Beckman Coulter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

TER, DLB, LRL, MAR, CJP, and DD are employees of Beckman Coulter. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Beckman Coulter, the stylized logo, and the Beckman Coulter product and service marks mentioned herein are trademarks or registered trademarks of Beckman Coulter, Inc. in the United States and other countries.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

White, J., Shenoy, B.V., Tutrone, R.F. et al. Clinical utility of the Prostate Health Index (phi) for biopsy decision management in a large group urology practice setting. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 21, 78–84 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-017-0008-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-017-0008-7

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances and future perspectives in the therapeutics of prostate cancer

Experimental Hematology & Oncology (2023)

-

Prostate health index (PHI) as an accurate prostate cancer predictor

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

Liquid biomarkers for early detection of prostate cancer and summary of available data for their use in African-American men

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2022)

-

Screening for prostate cancer: protocol for updating multiple systematic reviews to inform a Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care guideline update

Systematic Reviews (2022)

-

Integrating inflammatory serum biomarkers into a risk calculator for prostate cancer detection

Scientific Reports (2021)