Abstract

Background

Evidence on the association between perinatal maternal depression and children’s behavioral development is limited. We investigated the association between maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum and the risk of childhood behavioral problems using data from a birth cohort study.

Methods

Study subjects were 1199 mother–child pairs. Maternal depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale during pregnancy and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at 4 months postpartum. Children’s behavioral development at 5 years of age was assessed with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

Results

Compared with children whose mothers did not experience depressive symptoms during pregnancy, those whose mothers did experience depressive symptoms during pregnancy had increased risk of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and low prosocial behavior. Maternal depressive symptoms at around 4 months postpartum were associated with increased risk of childhood emotional problems. Compared with children whose mothers did not experience depressive symptoms during the perinatal period, those whose mothers did experience depressive symptoms both during pregnancy and postpartum had a fivefold increased risk of childhood emotional symptoms and a threefold increased risk of peer problems.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that perinatal maternal depression is associated with behavioral problems in children.

Impact

-

Several epidemiological studies in Western countries have examined the association between perinatal maternal depression and children’s behavioral development, yet the results are conflicting and inconclusive.

-

There is limited evidence on this topic in Asia.

-

In our study using data from a prospective pregnancy birth cohort, maternal depressive symptoms around 4 months postpartum were associated with an increased risk of emotional symptoms in children aged 5 years.

-

Children whose mothers had exhibited depressive symptoms both during pregnancy and postpartum had a fivefold increased risk of childhood emotional symptoms and a threefold increased risk of peer problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The occurrence of depressive symptoms in mothers during pregnancy and the postpartum period is a common psychological disorder.1 Because infants in the fetal and early postnatal stages are particularly sensitive to environmental factors, exposure to adverse conditions such as poor nutrition status,2 smoking,3 and maternal diseases4 might have long-lasting consequences for development, behavior, and physical health in children.

Previous studies have examined whether maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the early postpartum period affect children’s emotional and behavioral development.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 A pregnancy cohort study in Canada showed that persistent higher scores on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) from pregnancy to 1 year postpartum was associated with an increased risk of both externalizing and internalizing behaviors in children at 3 years.8 A Swedish population-based longitudinal mother–infant study likewise showed that prenatal, postnatal, and persistent maternal depression from pregnancy through postpartum month 6 were positively associated with the risk of internalizing and externalizing problems in children aged 18 months, although these associations were attenuated after adjustment for postnatal maternal bonding.9 In a cross-sectional study conducted in Pakistan, there was a significant positive association between maternal depression and the prevalence of emotional, conduct, and peer problems among children aged 5 years.12 In a cohort study in the US, on the other hand, no association was observed between postpartum depressive symptoms at 8 weeks and the risk of an infant exhibiting externalizing or internalizing behaviors at 12 months of age.11 Thus, the available results on the association between perinatal maternal depressive symptoms and children’s behavioral development are conflicting and inconclusive due to differences in study design, study population, study size, and the measurement tools used to assess maternal depressive symptoms and children’s development across studies. Furthermore, studies on this topic have been conducted mainly in Western countries; in Asia, there have been few large-scale cohort studies with detailed pre- and postnatal information. There are some relevant differences between Western and Asian countries in cultural contexts, customs, and traditional norms related to reproduction and the role of women.13,14 For example, premarital pregnancy, conflict with in-laws, and work–life imbalance have been suggested as uniquely Asian cultural-related factors for perinatal depression that do not affect Western women as powerfully.13,14 It is possible that these cultural factors affect the development of perinatal maternal depressive symptoms9 and thus shape the association between perinatal maternal depressive symptoms and childhood behavioral problems. Thus, further research is needed to accumulate data on this topic in Asian countries.

In the present study, to assess whether perinatal maternal depressive symptoms influence children’s behavioral development, we investigated the association between maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum and the risk of childhood behavioral problems, using data from fetal life to 5 years of age collected in the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study (KOMCHS).

Methods

Study population

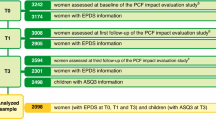

The KOMCHS is a prospective cohort study started before birth that aims to elucidate the onset-related factors and prevention factors of maternal and child health problems. The baseline survey of the KOMCHS has been described in detail elsewhere.15 In the baseline survey between April 2007 and March 2008, a set of leaflets explaining the KOMCHS, an application form to participate in the KOMCHS, and a self-addressed and stamped return envelope were provided to as many pregnant women as possible in 423 obstetric hospitals in seven prefectures on Kyushu Island in southern Japan, with a total population of approximately 13.26 million, and in Okinawa Prefecture, an island chain in the southwest of Japan, with a total population of nearly 1.37 million. Pregnant women who were willing to participate in the KOMCHS mailed the application form containing a written description of their personal information to the data management center. After determining eligibility based on this personal information, research technicians explained the KOMCHS in detail to each eligible participant by telephone and obtained permission to send them a self-administered questionnaire. A total of 1757 pregnant women between the 5th and 39th week of pregnancy gave their written informed consent to participate in the KOMCHS and answered a self-administered questionnaire in the baseline survey. Of the 1757 women, 1590, 1527, 1430, 1362, 1305, 1264, and 1201 mother–child pairs participated in all surveys from the baseline survey to the second (after delivery), third (around four months postpartum), fourth (around 12 months postpartum), fifth (around 24 months postpartum), sixth (around 36 months postpartum), seventh (around 48 months postpartum), and eighth (around 60 months postpartum) surveys, respectively (Fig. 1). We excluded two mother–child pairs due to missing data on the factors under study. Thus, analyses were conducted on 1199 pairs. The KOMCHS was approved by the ethics committees of the Faculty of Medicine, Fukuoka University and Ehime University Graduate School of Medicine.

Exposure measures

The Japanese version16 of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)17 was filled out in the baseline survey during pregnancy. The CES-D consists of 20 questions. Each question is scored on a scale of 0 to 3 according to the frequency of the symptoms, and the total CES-D score ranges from 0 to 60. We defined depressive symptoms as present when a participant had a CES-D score ≥16.

Maternal postpartum depressive symptoms were assessed at the third survey (around 4 months postpartum) using the EPDS.18 The EPDS is a 10-item self-reported scale developed to screen for perinatal depressive symptoms. Each item was rated on a four-point scale (0 to 3) such that the range of possible scores was from 0 to 30, with a higher score representing a greater severity of depression. When the test is used for screening purposes in the postpartum period, Cox et al. proposed a cutoff score of 10.18 However, a validation study among Japanese women demonstrated that a cutoff score with a threshold of 8/9 had a specificity of 93% and a sensitivity of 75% for depression.19 Thus, in the present study, we defined postpartum depressive symptoms as present when a subject had a score ≥9.

Outcome measures

In the eighth survey, children’s behavior at age 5 years was assessed by the Japanese parent-report version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), which was designed to assess the behavior and emotions of 3- to 16-year-old children.20 The SDQ consists of five scales—an emotional problems scale, a conduct problems scale, a hyperactivity scale, a peer problems scale, and a prosocial scale—each scored based on five items, resulting in 25 items total. Each item is rated on a three-point scale: “not true” (0), “somewhat true” (1), and “certainly true” (2). Positively worded items were reverse-scored. The items on each scale were summed to generate a score that could range from 0 to 10. These scale scores were then categorized as normal, borderline, or abnormal according to cutoff points that had previously been reported in a sample of Japanese children.21 We dichotomized the five scale scores, comparing children with borderline and abnormal scores with children with normal scores; we defined emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and low prosocial behavior as present when a child had a borderline or abnormal score in the respective scale.

Covariates

The questionnaire in the baseline survey included questions about maternal age, gestation, region of residence, number of children, maternal and paternal education, household income, and maternal secondhand smoke exposure at home and at work. The baseline survey also included a semi-quantitative, comprehensive dietary history questionnaire assessing consumption of six types of alcoholic beverages: beer, Japanese sake (rice wine), shochu (a distilled alcoholic beverage made in Japan), chuhai (made with shochu and carbonated water), whisky, and wine22,23 during the month preceding the completion of the questionnaire.

In the second survey, the questionnaire asked about the baby’s sex, birth weight, date of birth, and maternal smoking during pregnancy.

Information on household smoking and breastfeeding duration was obtained from the questionnaires in the third and fourth surveys. Household smoking exposure during the first year of life was defined as positive if the child had lived with at least one smoker at the third or fourth survey. Breastfeeding duration was defined as the length of the period during which infants received breast milk, regardless of exclusivity. The questionnaire in the fourth survey also included a question on daily TV watching time.

Statistical analysis

Maternal age, gestation at baseline, region of residence at baseline, number of children at baseline, maternal and paternal educational levels, household income, maternal alcohol intake during pregnancy, child’s birth weight, child’s sex, breastfeeding duration, maternal smoking during pregnancy, household smoking exposure during the first year of life, and TV watching time at the third survey were selected a priori as potential confounding factors. Maternal age, gestation, and birth weight were used as continuous variables.

In an analysis of the additive effect of maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy and around four months postpartum, the mothers were classified into four mutually exclusive categories: no maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy or postpartum (none); maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy only (during pregnancy only); maternal depressive symptoms during the postpartum period only (postpartum only); and maternal depressive symptoms both during pregnancy and postpartum (both).

Logistic regression analysis was conducted to estimate crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for behavioral problems in relation to perinatal maternal depressive symptoms. All statistical analyses were carried out using the SAS software package version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Of the 1199 children aged 59–71 months, the prevalence values of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and low prosocial behavior were 12.9%, 19.4%, 13.1%, 8.6%, and 29.2%, respectively. Of the 1199 mothers, 218 (18.2%) scored above the cutoff on the CES-D during pregnancy, 99 (8.3%) scored above the cutoff on the EPDS postpartum, and 52 (4.3%) experienced maternal depressive symptoms both during pregnancy and postpartum. Detailed characteristics of the 1199 parent–child pairs are shown in Table 1. The mean maternal age and gestation at baseline were 31.6 years and 18.1 weeks, respectively. Participating parents tended to be highly educated.

Table 2 summarizes crude and adjusted ORs and their 95% CIs for behavioral problems in relation to perinatal maternal depressive symptoms. In adjusted models, compared with children whose mothers did not have depressive symptoms during pregnancy, those whose mothers had experienced depressive symptoms during pregnancy had an increased risk of emotional symptoms (adjusted OR = 2.16, 95% CI: 1.44–3.21), conduct problems (adjusted OR = 1.91, 95% CI: 1.35–2.45), hyperactivity (adjusted OR = 1.64, 95% CI: 1.08–2.45), peer problems (adjusted OR = 2.01, 95% CI: 1.25–3.18), and low prosocial behavior (adjusted OR = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.08–2.06).

Maternal depressive symptoms around 4 months postpartum were associated with an increased risk of childhood emotional problems (adjusted OR = 3.22, 95% CI: 1.93–5.27). No material associations were observed between maternal depressive symptoms around 4 months postpartum and a risk of conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, or prosocial behavior.

In an analysis of the additive effect (Table 3), compared with children whose mothers did not experience depressive symptoms at any time during the perinatal period, those whose mothers had experienced depressive symptoms both during pregnancy and postpartum had an increased risk of childhood emotional symptoms (adjusted OR = 5.24, 95% CI: 2.74–9.87) and peer problems (adjusted OR = 3.12, 95% CI: 1.43–6.38). Maternal depressive symptoms only during pregnancy were associated with an increased risk of conduct problems (adjusted OR = 2.22, 95% CI: 1.50–3.25), hyperactivity (adjusted OR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.09–2.68), and low prosocial behavior (adjusted OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.02–2.12).

Furthermore, we performed an additional analysis of 1145 children excluding the 54 mothers who reported having a diagnosis of depression at the baseline survey. This analysis did not meaningfully change our results.

Discussion

In the present cohort study, we found that maternal prenatal depressive symptoms were associated with an increased risk of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and low prosocial behavior. A positive association was observed between maternal postpartum depressive symptoms at around 4 months and the risk of emotional symptoms. In the additive effect analysis, having maternal depressive symptoms both during pregnancy and postpartum was associated with a fivefold increased risk of emotional problems and a threefold increased risk of peer problems in children.

Our results are partly consistent with previous findings regarding the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy and children’s behavioral problems. In a cross-cohort consistency study (Generation R study and ALSPAC), the Generation R Study found that maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy were not associated with the risk of child emotional problems, whereas ALSPAC found a positive association.10 In a Greek cohort study including 288 subjects, maternal depressive symptoms identified by the EPDS at 28–32 weeks of gestation were positively associated with the risk of peer problems and low prosocial behavior, but not emotional problems, conduct problems, or hyperactivity, in children at 4 years.24

Regarding the relationship between maternal postpartum depressive symptoms and children’s behavioral problems, a prospective study in England showed that maternal depression at 8 weeks postpartum was positively associated with the risk of conduct problems in boys, but not girls, at 4 years, whereas there was no association between maternal postpartum depression and the risk of hyperactivity or emotional problems in either sex.3 In a US cohort study, there was no association between maternal postpartum depression symptoms evaluated by the EPDS at 8 weeks postpartum and the risk of externalizing or internalizing behaviors in 247 children at 12 months.11 These findings were inconsistent with our results.

Several studies have recently been conducted using trajectory models to assess not only the independent effects of prenatal and postnatal maternal depressive symptoms, but also those of recurring and persistent maternal depressive symptoms on children’s behavioral development.8,9,25,26,27 In a birth cohort study in France in 1183 subjects, five trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms were identified: no symptoms, persistent intermediate-level depressive symptoms, persistent high-level symptoms, high symptoms during pregnancy only, and high symptoms during the child’s preschool years only.25 Compared with children whose mothers had no depressive symptoms, those whose mothers had persistent depressive symptoms, irrespective of whether they were intermediate or high, were more likely to have emotional symptoms, conduct problems and hyperactivity at age 5 years.25 In an Australian cohort study of 1085 subjects, three trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum were identified: no or few symptoms, persistent subclinical symptoms, and persistent and increasing high symptoms26; children of mothers assigned to the “persistent subclinical” and “persistent and increasing high symptoms” trajectories had significantly more emotional-behavioral difficulties than did children of mothers assigned to the “no or few” trajectory.26 In prospective cohort studies in the Netherlands8 and Canada,27 maternal persistent depressive symptoms were positively associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in children. Our finding of positive associations between maternal depressive symptoms both during pregnancy and postpartum and the risks of childhood emotional symptoms and peer problems, indicating an additive effect, are in partial agreement with these findings. Like our present findings, these previous findings suggest that maternal depressive symptoms that persist from pregnancy through the postpartum period might increase the child’s risk of emotional (internalizing) problems in children. Fransson et al.9 have indicated that further adjustment for postpartum bonding attenuated the negative effect of maternal persistent depression on internalizing problems at 18 months. Like our present study, these previous studies8,25,26,27 did not incorporate factors pertaining to the mother–infant relationship into their analyses. On the other hand, our results showing no association between maternal depressive symptoms both during pregnancy and postpartum and a risk of conduct problems or hyperactivity were inconsistent with those of other studies.8,25,27 In the present study, maternal depressive symptoms were assessed only once prenatally and once postnatally; furthermore, the timing of our postpartum assessment was relatively early (at 4 months postpartum) compared to those in other studies (final assessment point of other previous studies: 12–36 months postpartum). This discrepancy is likely to have contributed to the discrepancies among our results.

The potential mechanisms by which perinatal maternal depressive symptoms impact children’s behavioral development remain unknown. Both genetic and environmental factors are likely to impact children’s behavior.28,29,30 Depressive mothers are likely to transmit to their children a genetic susceptibility to mental health difficulties.28 The association between the mental health symptoms of a mother and her child might also be bidirectional, as a child is likely to be distressed when its mother’s behaviors reflect depressive symptoms and a mother is likely to be distressed by her child’s behavioral problems.28,29 Furthermore, elevated maternal depressive symptoms are likely to be associated with problematic parenting practices, which themselves might be a risk factor for children who are, for genetic reasons, particularly sensitive to their environments.28,29,30

Our study has several strengths, including our use of data from a pre-birth cohort with a relatively large sample size and a long duration of follow-up. In addition, our analysis took several important confounding factors into account, although potential residual confounding could not be completely excluded.

Several limitations of the current study deserve attention. Of the 1757 participants at the baseline survey, only 1199 mother–child pairs were included in the present study. There were no material differences between the 558 subjects who dropped out prior to the eighth survey or those who were excluded from the present study and the 1199 participants who were included in the present study with regard to distribution of number of children, maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy, or maternal alcohol intake during pregnancy. Compared with nonparticipants in follow-up surveys or subjects who were excluded due to missing data, study subjects in the present study were more likely to be older, to have participated in the baseline survey earlier in their gestation, to live in Fukuoka Prefecture, and to report high maternal and paternal educational levels and high household income. Moreover, at baseline, it was impossible to calculate the participation rate because of a lack of exact figures on the number of pregnant women who were provided with a set of leaflets explaining the KOMCHS, an application form, and a self-addressed and stamped return envelope by the 423 collaborating obstetric hospitals. Furthermore, of the 1757 mothers at baseline, 978 mothers lived in Fukuoka Prefecture. According to data collected by the government of Fukuoka Prefecture, the number of childbirths was 46,393 in 2007 and 46,695 in 2008; thus, the participation rate must have been low. Therefore, our study population was not representative of Japanese women in the general population, which limits our study’s generalizability. In fact, our study subjects were more educated than women in the general population.31 Cigarette-smoking status in our study population, on the other hand, was likely to be similar to that in the general population.32

Because the SDQ was filled out by the children’s mothers, we cannot rule out the possibility of depressed mother reporter bias, whereby a depressive mother is likely to report more behavioral problems in her children than a non-depressed mother would. In many studies on the association between maternal psychological distress and children’s outcomes, the source of information on the children’s behavioral outcomes has been their mothers. If additional third-party objective assessments such as reports from the children’s schools had been included alongside the parental assessments, the study would have been strengthened. The SDQ, however, is widely used and is a well-validated tool. Moreover, it is uncertain whether the cutoff points for dichotomization of the outcomes under study were reasonable, although they were based on a previous report conducted in Japan.21

In the present study, we assessed maternal depressive symptoms using self-reported measurements rather than clinical diagnostic interviews, leading to the probable misclassification of maternal depressive symptoms. As mentioned above, maternal depressive symptoms were assessed only once prenatally and once postnatally rather than multiple times. Moreover, several important factors related to child outcomes were not available in this study, including the mental health status of the mother’s partner, parenting behavior, and parental mental health when the child was 5 years old.

Although information on maternal history of depression was obtained at the baseline survey, no information about any medical treatments administered to the mother or child was available in this study.

Conclusions

Our results indicated that maternal prenatal depressive symptoms were associated with an increased risk of all five of the child behavior problems examined in the present study (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and low prosocial behavior). Maternal postpartum depressive symptoms at around 4 months were positively associated with the child’s risk of emotional symptoms. In addition, compared with children of mothers without depressive symptoms at any time in the perinatal period, children of mothers with depressive symptoms both during pregnancy and postpartum had a fivefold increased risk of emotional problems and a threefold increased risk of peer problems at 5 years old. Because of this study’s numerous limitations, caution is advised when interpreting these results. However, our findings confirm the importance of paying greater attention to maternal depressive symptoms in the perinatal period. Long-term maternal mental health care during pregnancy and the postpartum period may be an opportunity for primary prevention of behavioral problems as well as secondary prevention of childhood mental health disorders. To this end, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare established the “Healthy Parents and Children 21 (secondary phase)” program in 2015, which will establish a seamless support system for pregnant women and infants that includes mental health care for mothers.33

More research is needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying the long-lasting effects of perinatal maternal depressive symptoms on childhood behavioral problems and to determine whether treating perinatal maternal depression can actually prevent childhood behavioral problems.

References

Arifin, S. R. M., Cheyne, H. & Maxwell, M. Review of the prevalence of postnatal depression across cultures. AIMS Public Health 5, 260–295 (2018).

Barker, D. J. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ 311, 171–174 (1995).

Tanaka, K., Miyake, Y., Furukawa, S. & Arakawa, M. Perinatal smoking exposure and behavioral problems in Japanese children aged 5 years: The Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study. Environ. Res. 151, 383–388 (2016).

O’Connor, T. G., Heron, J., Golding, J., Glover, V. & ALSPAC Study Team. Maternal antenatal anxiety and behavioural/emotional problems in children: a test of a programming hypothesis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 44, 1025–1036 (2003).

Goodman, S. H. et al. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 14, 1–27 (2011).

Beck, C. T. Maternal depression and child behaviour problems: a meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 29, 623–629 (1999).

Talge, N. M., Neal, C., Glover, V. & Early Stress, Translational Research and Prevention Science Network: Fetal and Neonatal Experience on Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48, 245–261 (2007).

Kingston, D. et al. Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the first 12 months postpartum and child externalizing and internalizing behavior at three years. PLoS ONE 13, e0195365 (2018).

Fransson, E. et al. Maternal perinatal depressive symptoms trajectories and impact on toddler behavior—the importance of symptom duration and maternal bonding. J. Affect. Disord. 273, 542–551 (2020).

Van Batenburg-Eddes, T. et al. Parental depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy and attention problems in children: a cross-cohort consistency study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 54, 591–600 (2013).

Vafai, Y., Steinberg, J. R. & Shenassa, E. D. Maternal postpartum depressive symptoms and infant externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Infant Behav. Dev. 42, 119–127 (2016).

Nadeem, S., Rafique, G. & Chachar, Y. S. Maternal depression: a major risk factor for psychosocial wellbeing among preschoolers. Asian J. Psychiatr. 37, 85–89 (2018).

Roomruangwong, C. & Epperson, C. N. Perinatal depression in Asian women: prevalence, associated factors, and cultural aspects. Asian Biomed. 5, 179–193 (2011).

Takegata, M., Ohashi, Y., Lazarus, A. & Kitamura, T. Cross-national differences in psychosocial factors of perinatal depression: a systematic review of India and Japan. Healthcare (Basel) 5, 91 (2017).

Miyake, Y., Tanaka, K., Okubo, H., Sasaki, S. & Arakawa, M. Fish and fat intake and prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy in Japan: baseline data from the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 47, 572–578 (2013).

Shima, S., Shikano, T., Kitamura, T. & Asaim, M. New self-rated scale for depression (in Japanese). Jpn J. Clin. Psychiatry 27, 717–723 (1985).

Radloff, L. S. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401 (1977).

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M. & Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 150, 782–786 (1987).

Okano, T. et al. Validation and reliability of Japanese version of the EPDS (in Japanese). Arch. Psychiatr. Diagn. Clin. Eval. 7, 525–533 (1996).

Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 38, 581–586 (1997).

Matsuishi, T. et al. Scale properties of the Japanese version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): a study of infant and school children in community samples. Brain Dev. 30, 410–415 (2008).

Sasaki, S., Yanagibori, R. & Amano, K. Self-administered diet history questionnaire developed for health education: a relative validation of the test-version by comparison with 3-day diet record in women. J. Epidemiol. 8, 203–215 (1998).

Sasaki, S. et al. Serum biomarker-based validation of a self-administered diet history questionnaire for Japanese subjects. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo) 46, 285–296 (2000).

Koutra, K. et al. Maternal depression and personality traits in association with child neuropsychological and behavioral development in preschool years: mother-child cohort (Rhea Study) in Crete, Greece. J. Affect Disord. 217, 89–98 (2017).

van der Waerden, J. et al. Maternal depression trajectories and children’s behavior at age 5 years. J. Pediatr. 166, 1440–1448 (2015).

Giallo, R., Woolhouse, H., Gartland, D., Hiscock, H. & Brown, S. The emotional-behavioural functioning of children exposed to maternal depressive symptoms across pregnancy and early childhood: a prospective Australian pregnancy cohort study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 24, 1233–1244 (2015).

Cents, R. A. et al. Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms predict child problem behaviour: the Generation R study. Psychol. Med. 43, 13–25 (2013).

Oppenheimer, C. W., Hankin, B. L., Young, J. F. & Smolen, A. Youth genetic vulnerability to maternal depressive symptoms: 5-HTTLPR as moderator of intergenerational transmission effects in a multiwave prospective study. Depress. Anxiety 30, 190–196 (2013).

McAdams, T. A. et al. The relationship between parental depressive symptoms and offspring psychopathology: evidence from a children-of-twins study and an adoption study. Psychol. Med. 45, 2583–2594 (2015).

Silberg, J. L., Maes, H. & Eaves, L. J. Genetic and environmental influences on the transmission of parental depression to children’s depression and conduct disturbance: an extended children of twins study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 51, 734–744 (2010).

Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications, 2002. 2000 Population Census of Japan, Vol. 3-2-40, Labour Force Status of Population, Industry (Major Groups) of Employed Persons, and Education, Fukuoka-ken. Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications, Tokyo.

National Institute of Health and Nutrition, 2010. The National Health and Nutrition Survey Japan, 2007. Daiichi Shuppan, Tokyo.

Healthy Parents and Children 21. https://sukoyaka21.jp/healthy-parents-and-children-21 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Kyushu Branch of the Japan Allergy Foundation, the Fukuoka Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, the Okinawa Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, the Miyazaki Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, the Oita Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, the Kumamoto Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, the Nagasaki Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, the Kagoshima Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, the Saga Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, the Fukuoka Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the Okinawa Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the Fukuoka City Government, and the Fukuoka City Medical Association for their valuable support. These organizations did not have any influence on the study design; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 19590606, 20791654, 21590673, 22592355, 22119507, 24390158, 25463275, 25670305, 17K12011JP, 17H04135JP, and 21H03199JP and by Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants for Research on Allergic Disease and Immunology and Health Research on Children, Youth and Families from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MY was responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data and the drafting of the manuscript. KT contributed to the study concept and design, the data acquisition, and was responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data and the drafting of the manuscript. YM contributed to the study concept and design, the data acquisition, and assisted in manuscript preparation. MA contributed to the study concept and design and the data acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent statement

Mothers gave their written informed consent to participate in the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yamada, M., Tanaka, K., Arakawa, M. et al. Perinatal maternal depressive symptoms and risk of behavioral problems at five years. Pediatr Res 92, 315–321 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01719-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01719-9

This article is cited by

-

Trajectories and Associations Between Maternal Depressive Symptoms, Household Chaos and Children's Adjustment through the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Four-Wave Longitudinal Study

Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology (2023)

-

Association of maternal psychological distress and the use of childcare facilities with children's behavioral problems: the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study

BMC Psychiatry (2022)

-

Tryptophan intake is related to a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy in Japan: baseline data from the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study

European Journal of Nutrition (2022)