Abstract

Background

Obtaining informed consent for clinical research in the pediatric emergency department (ED) is challenging. Our objective was to understand the factors that influence parental consent for ED studies.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey assessing parents’ willingness to enroll their children into an ED research study. Parents reporting a willingness to enroll in ED studies were presented with two hypothetical scenarios, a low-risk and a high-risk study, and then asked about decision influencers affecting consent. Parents expressing a lack of willingness to enroll were asked which decision influencers impacted their consent decision.

Results

Among 118 parents, 90 (76%) stated they would be willing to enroll their child into an ED study; of these, 86 (96%) would consent for a low-risk study and 54 (60%) would consent for a high-risk study. Caucasian parents, and those with previous research exposure, were more likely to report willingness to participate. Those who would consent to the high-risk study cited “benefits that research would provide to future children” most strongly influenced their decision to agree.

Conclusions

ED investigators should highlight the benefits for future children and inquire about parents’ previous exposure to research to enhance ED research enrollment. Barriers to consent in non-Caucasian families should be further investigated.

Impact

-

Obtaining consent for pediatric emergency research is challenging and this study identified factors influencing parental consent for research in EDs.

-

Benefits for future children and parents’ previous research experience were two of the most influential factors in parents’ willingness to consent to ED research studies.

-

These findings will help to improve enrollment in ED research studies and better our understanding of how to promote the health and well-being of pediatric patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obtaining informed consent for children in the emergency department (ED) research is challenging. Little is known about the factors that influence parents’ willingness to consent to their child’s participation in emergency research.1 Most existing literature on parental consent has been conducted within inpatient clinical trials and few assessments have focused on emergency settings. In addition, enrollment rates for children in clinical research studies, particularly in the ED, still lags behind that of adults.2 Although these lower enrollment rates may be due to many different factors, it highlights the potential opportunity for improvements in the consent process. Advances in clinical care are often driven by empirical research; therefore, understanding the factors that influence parental consent within pediatric EDs may help to promote the health and well-being of pediatric patients.

Parental beliefs about clinical research and motives for participation are well documented.3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 Prior research suggests that parents believe that clinical research is necessary3 and that participation is often driven by the benefits provided to their child and to science.4,5,6,9 Additionally, parents who agree to participate in inpatient clinical research report being satisfied with the study explanations provided during the consent process7,8 and with the time that they received to review the treatment options.8,9,10 Notably, participation in clinical research by race and ethnicity suggests that Caucasian parents are more likely to consent for their child to participate in clinical research compared to Black and Hispanic parents.11 This body of literature highlights that many parents, especially those who identified as Caucasian, are willing to participate in inpatient clinical research and are often satisfied with the consent process; however, explorations regarding consent in pediatric emergency departments are limited.

Consent in pediatric EDs is often time-sensitive and highly unpredictable.12 Parents are likely to experience high levels of emotional stress and confusion,13,14 which can result in a lack of willingness to participate in emergency research. This stressful and unpredictable environment in the ED is in contrast to office and inpatient settings, where research visits are often scheduled. In addition, parents often have the time to thoroughly review consent forms, as well as the opportunity to take consent forms home to review.9 Therefore, the prior findings of parental consent and pediatric research may not be applicable for ED-based research. The emerging literature on deferred parental consent within emergency contexts, which takes place post treatment, has begun to explore these potential differences.15,16 This research suggests that parents prefer to have an explanation of the research that is tailored to their concerns when they are asked to provide emergency deferred consent.15 Guidelines for deferred consent, which were developed from interviews and surveys also suggest that it is important to clearly discuss why the research is being conducted and the benefits it may have for future children.16 Research on ED consent that occurs before treatment and perceptions about research from those who do not wish to participate remains relatively unexplored.

Identification of barriers and facilitators to enrollment of children in emergency medicine research is necessary. Strategies to enhance approaches to consent and create best practices can improve the number of subjects enrolled, and consequently the quality of findings for pediatric emergency research. The objective of this study was to understand the factors that influence parental consent for pediatric emergency research that occurs pretreatment, in order to inform future efforts for enrollment in ED studies.

Methods

Design and setting

This was a pilot study utilizing a cross-sectional survey design. Electronic surveys were administered on REDCap to a convenience sample of parents who brought their children into an urban, tertiary-care pediatric ED from July 2017 to September 2017 and January 2018 to March 2018. Enrollment periods were selected by convenience, owing to the competition from other studies concurrently being conducted in the ED. The study was granted exempt status by the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Participants

Parents and guardians of children who presented to the ED between the ages of 18 and 84 years and those who were English- or Spanish-speaking were invited to participate. Parents who were minors, <18 years of age, and older adults with special IRB exemptions, >84 years of age, were excluded. ED research assistants (RAs) approached parents for participation after placement in an ED room between 7:00 a.m. and midnight daily when available.

Study procedures and data collection

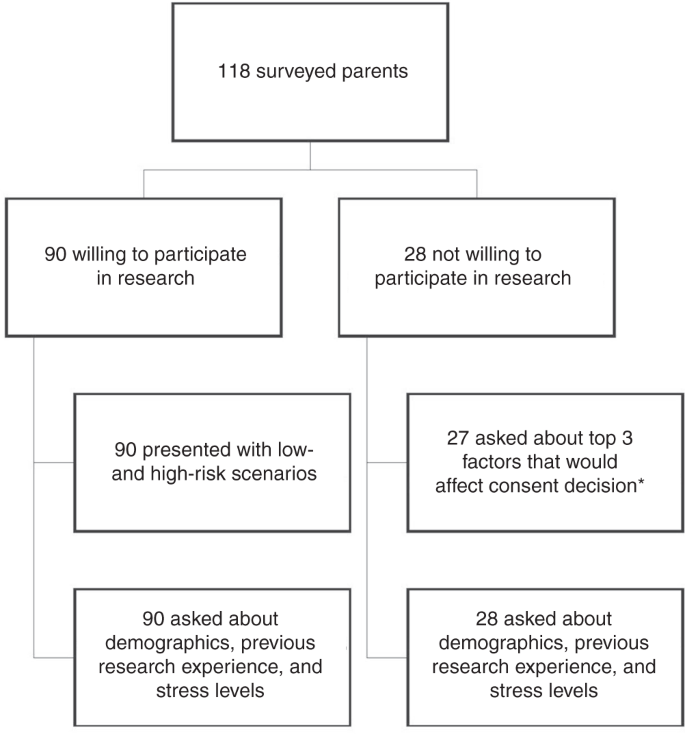

Parents and legal guardians who agreed to answer survey questions were informed about the study purpose, and specifically asked, “If presented with an opportunity to participate in a relevant research study pertaining to your child, would you be willing to participate?” Parents who reported that they would be willing to potentially enroll their child into research were subsequently presented with two hypothetical scenarios, a low-risk head injury study and a high-risk interventional asthma study (Appendix 1). Parents were only presented with study scenarios; designation of “low risk” or “high risk” was not known to respondents. The hypothetical low-risk study entailed a simple retrospective chart review, while the high-risk study involved a medical intervention trial with the placement of an intravenous line for a study medication. Within each scenario, parents were provided with a brief description of study participation details and then asked if they would be willing to consent for their child to participate in either hypothetical study. After reporting their agreement or disagreement to consent to the hypothetical scenarios, seven decision influencers for consent were assessed. Decision influencers were selected based on existing literature surrounding factors informing parental consent. Decision influencers included benefits to others,4,5,16 benefits to your child,4,9 stress and anxiety,8,13 presence of a supporting individual,17,18 a clear and concise study explanation,12,16 previous experience with research,16,19 and consent in their native language.20,21 Questions about obtaining consent in their native language were only asked if the parents primarily spoke Spanish. Each decision influencer was measured using a 5-point Likert scale (5—strongly agree; 1—strongly disagree). Likert scale responses were dichotomized for interpretability with those responding 4 or 5 on the scale were combined into the “agreed” category and those responding 1, 2, or 3 were combined into the “disagree” category. A flowchart of study procedures is presented in Fig. 1.

Parents who initially stated that they would not consider enrolling their child into a research study during their ED visit were asked to answer additional questions to help the research team improve interactions with patients and families. Individuals who agreed to answer these additional questions were queried about the top three decision influencers that would most positively influence their decision to consent. Individuals who did not agree to answer additional questions were not included in order to respect ethical guidelines and to follow a recent ethical movement to protect those that decline to participate in research.22

Demographics were collected for all participants, as were two general questions about their past experiences with medical research and about their current levels of stress and anxiety in the ED. Demographics included sex, income, race, ethnicity, education, insurance, preferred language, parental age, and child age (Table 1).

Data analysis

Data were summarized using standard descriptive statistics. Comparisons and associations between willingness to consent, parental factors, and decision influencers were made using χ2 analyses, Fisher’s exact test, and independent-samples t tests. G*Power was used to calculate post hoc power analyses with at least 80% power. Analyses revealed that the sample size was sufficient to detect significant differences within this study. Fisher’s exact test was used to explore decision influencers in the low-risk study because some frequencies were <5.23 Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were also calculated where appropriate. All analyses were run in IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 (Chicago, IL) and SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

In total, 118 parents were initially approached for study participation. Ninety (76%) parents stated that they would be willing to enroll their child into a relevant ED research study. Among the 90 parents who reported willingness to enroll their child into a potential research study, 86 (96%) stated that they would consent to the low-risk study, and 54 (60%) stated they would consent to the high-risk study.

Race and previous research experience had the strongest association with a parent’s potential willingness to participate in any form of pediatric emergency research (Table 1). Individuals who identified as Caucasian, in comparison to individuals who identified as non-Caucasians, were significantly more likely to state that they would participate in research (odds ratio (OR) = 3.02, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.15–7.88). Parents who had previously participated in clinical research were also significantly more likely to agree to consent for general research participation, as compared to those with no previous research experience (OR = 5.66, 95% CI: 1.25–25.56). Other parent and child factors, including child age, income, ethnicity, education, insurance, employment status, past experience with research, self-reported stress, and language, were not significantly associated with consent to general research (Table 1). Differences in parent and child factors influencing potential enrollment for the low-risk study were not investigated, as 96% of participants stated that they would consent to the low-risk study. For the high-risk study, no parent or child factors were significantly associated with potential enrollment (Table 2).

Several decision influencers were noted to impact consent into the high-risk study (Table 3). “Benefits to others” was most strongly associated with consent into the high-risk study (p < 0.001), followed by potential direct benefits of participation to their child (p = 0.017), the presence of a supporting individual (p = 0.037), and use of a clear and concise study explanation (p = 0.037). Additionally, 56% of parents who reported willingness to enroll in the high-risk study did not agree that the stress and anxiety from the current ER visit would impact their willingness to consent, as compared to parents who did not report willingness to consent to the high-risk research (p = 0.006). When comparing the relationship of decision influencers on potential participation in the low-risk study, none of the decision influencers were found to have a significant association. However, 75 of the 86 parents (87%) who would consent to the low-risk study agreed that benefits to others would most strongly influence their decision to consent.

Discussion

This study contributes meaningful and novel information about the determinants associated with parental consent for their children to participate in pediatric emergency research. Race and parent’s previous experience with research played an influential role in the likelihood of consenting to an emergency research study. When investigating decision influencers, we determined that parental consent was positively impacted by research that was of benefit to the future of pediatric health. With respect to high-risk, interventional studies, the direct benefits provided to their child, the presence of a supporting individual, and clear and concise study explanations also positively influenced the decision to consent. Interestingly, no specific barriers or facilitators were associated with the decision to consent for low-risk studies such as chart reviews. The results of our study can assist future researchers in developing optimal strategies for approaching parents in ED settings to consent for participation in pediatric emergency research.

Similar to prior studies which found that participation in pediatric research was primarily motivated by a sense of altruism,1,16,17,18 parents in our study reported that they would be more willing to consent to a high-risk study if they knew it would help future children experiencing a similar problem. This factor had a greater association than potential benefits of research participation provided to their own child, which was the second most impactful decision influencer. These findings suggest that although parents do take their own child’s welfare into account, they also heavily weigh the health and well-being of other children who may potentially benefit from research when making their consent decision. Importantly, high-risk studies with greater potential to expose children to risks have lower rates of participation,24 which was also reflected in our study. Although risk and potential danger may always act as a deterrent, future high-risk studies may benefit from our findings, as parents seem to value the humanitarian benefits of high-risk ED research, and may be more willing to participate if they are provided information about the altruistic value of the research.

The use of clear and concise study explanations and the presence of a supporting individual were among the key influencers that motivated the decision to consent for the high-risk study. It has been well documented that parents want to understand the nature of the study for which they are allowing their child to participate.12,16 A lack of comprehension and understanding about the study often results in a lack of participation.25 Additionally, the role and presence of a support structure, such as a significant other, relative, or close friend, when making difficult decisions may be extremely helpful.17,18 Thus, ED researchers may benefit from encouraging parents to discuss the risks and benefits of ED research participation with a significant other or close friend before making a consent decision. Based on the findings of our study, pediatric ED-based research would benefit by helping families to feel more supported and well-informed during enrollment and consent.

For pediatric emergency research in general, previous participation and experience with clinical research were associated with a positive decision to consent. Among parents who had previously participated in the research, the likelihood of consenting was nearly six times higher. This relationship between parents’ prior experience with research and the willingness to consent to future studies suggests that parents who are comfortable with the research process are more likely to subsequently participate. Although the link between prior experiences and future participation has not been widely explored, prior investigations on deferred emergency consent suggest that parents with previous experience with deferred consent are more likely to provide deferred consent in the future.16,19 Further, these findings highlight the importance of both assessing for previous experience with research and the importance of appropriate conduct as past experiences with research was demonstrated to play a major role in future participation. In sum, parents who feel more comfortable with the consent process and study procedures may be more willing to enroll their child into research and continue to do so over time.

In line with existing knowledge,20,26 we also found that a lower percentage of participants who identified as non-Caucasian compared to individuals who identified as Caucasian agreed to consent to general research, while there were no differences found in ethnicity. One explanation for these results is that there may be medical distrust among racial minorities that stems from a history of discriminatory medical research and medical practices, as well as a legacy of mistreatment.27,28 The infamous Tuskegee syphilis study of 1932 purposely withheld curative treatment from over 400 black men with syphilis in order to unethically observe the natural course of the disease.27 Although the medical community condemned such research and discriminatory actions in 1972, our research and the research of others suggest that minoritized people remain skeptical of informed consent.28 These findings suggest that it may be essential to recognize this mistrust, validate concerns, and then promote transparency in the consent process. It also highlights the need for additional repair and culturally competent approaches for consent. Going forward, it will be important to continue to recognize medical distrust among racial minorities and validate these concerns while promoting transparency in the consent process.

Although previous studies have shown that parents are less likely to participate in clinical research during high levels of stress,29 our study results did not find that the current level of parental stress impacted decisions about consent. One possibility for these findings is that parents within our study may have underestimated their own stress and anxiety, as well as the impact of this stress on their consent decision, which is supported by prior research.30 An additional explanation may also be that stress and anxiety may not actually play as important a role with respect to parental consent, as previously believed. However, the current study did not measure parents current stress levels using a validated measure; therefore, future research that utilizes validated and reliable measures of stress and anxiety will be necessary in order to make more definitive conclusions.

Although this study has several important findings, our study is not without limitation(s). First, child age was the only child factor investigated in this study. It is possible that additional child factors may play an influential role in what may make parents more or less likely to consent to research. Second, this was a self-reported survey within a single, urban, tertiary-care ED. The answers are assumed to provide an accurate and honest representation of the parent’s beliefs, but these responses may suffer from social desirability bias and thus may not represent actual parental actions if asked to consent in a true research enrollment situation. By definition, parents who completed the survey are also amenable to a certain extent to participating in research in ED settings; therefore, actual refusals to research may not be represented within this sample and the results may be over-stated. Finally, this study took place within an academic tertiary-care ED, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Despite these limitations, this study provides important and novel information that should influence future efforts to encourage parental consent for pediatric emergency research.

Conclusion

We identified parental factors and beliefs that contribute to the enrollment of children within pediatric emergency department research studies. Parents who would consent for their children to participate in emergency research, do so out of a sense of altruism, and because of the benefits that it provides for their child. The presence of supporting individuals and explaining potential studies in a clear and concise manner can also motivate consent. Investigating the barriers to consenting families that identify as non-Caucasian as well as other factors that influence the decision to participate in low-risk studies are essential next steps. Overall, our findings support the importance of communicating the direct and future benefits of research for children when consenting families to pediatric emergency research studies.

References

Abernethy, L. E., Paulsen, E. L., Monuteaux, M. C., Berry, M. P. & Neuman, M. I. Parental perceptions of clinical research in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 29, 897–902 (2013).

Bourgeois, F. T. et al. Pediatric versus adult drug trials for conditions with high pediatric disease burden. Pediatrics 130, 285–292 (2012).

Morris, M. C., Besner, D., Vazquez, H., Nelson, R. M. & Fischbach, R. L. Parental opinions about clinical research. J. Pediatr. 151, 532–537 (2007).

Sammons, H. M., Atkinson, M., Choonara, I. & Stephenson, T. What motivates British parents to consent for research? A questionnaire study. BMC Pediatr. 7, 12 (2007).

Wendler, D., Abdoler, E., Wiener, L. & Grady, C. Views of adolescents and parents on pediatric research without the potential for clinical benefit. Pediatrics 130, 692–699 (2012).

Caldwell, P. H. Y., Butow, P. N. & Craig, J. C. Parents’ attitudes to children’s participation in randomized controlled trials. J. Pediatr. 142, 554–559 (2003).

Stenson, B. J., Becher, J. C. & McIntosh, N. Neonatal research: the parental perspective. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 89, F321–F324 (2004).

Ruccione, K., Kramer, R. F., Moore, I. K. & Perin, G. Informed consent for treatment of childhood cancer: factors affecting parents’ decision making. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 8, 112–121 (1991).

van Stuijvenberg, M. et al. Informed consent, parental awareness, and reasons for participating in a randomised controlled study. Arch. Dis. Child. 79, 120–125 (1998).

Eder, M. L., Yamokoski, A. D., Wittmann, P. W. & Kodish, E. D. Improving informed consent: suggestions from parents of children with leukemia. Pediatrics 119, e849–e859 (2007).

Natale, J. E. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in parental refusal of consent in a large, multisite pediatric critical care clinical trial. J. Pediatr. 184, 204–208 (2017).

Chamberlain, J. M. et al. Perceived challenges to obtaining informed consent for a time‐sensitive emergency department study of pediatric status epilepticus: results of two focus groups. Acad. Emerg. Med. 16, 763–770 (2009).

Heilbrunn, B. R. et al. Reducing anxiety in the pediatric emergency department: a comparative trial. J. Emerg. Med. 47, 623–631 (2014).

Holm, L. & Fitzmaurice, L. Factors influencing parent anxiety levels in a pediatric emergency department waiting area. Pediatr. Res. 56, 672 (2004).

Woolfall, K. et al. Doing challenging research studies in a patient-centred way: a qualitative study to inform a randomised controlled trial in the paediatric emergency care setting. BMJ Open 4, e005045 (2014).

Woolfall, K. et al. Fifteen-minute consultation: an evidence-based approach to research without prior consent (deferred consent) in neonatal and paediatric critical care trials. Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 101, 49–53 (2016).

Rabow, M. W., Hauser, J. M. & Adams, J. Supporting family caregivers at the end of life: they don’t know what they don’t know. JAMA 291, 483–491 (2004).

Greenberg, R. G. et al. Parents’ perceived obstacles to pediatric clinical trial participation: findings from the clinical trials transformation initiative. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 9, 33–39 (2018).

Molyneux, S. et al. ‘The words will pass with the blowing wind’: staff and parent views of the deferred consent process, with prior assent, used in an emergency fluids trial in two African hospitals. PLoS ONE 8, e54894 (2013).

Glickman, S. W. et al. Challenges in enrollment of minority, pediatric, and geriatric patients in emergency and acute care clinical research. Ann. Emerg. Med. 51, 775–780 (2008).

Kelly, M. L., Ackerman, P. D. & Ross, L. F. The participation of minorities in published pediatric research. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 97, 777 (2005).

Stiles, P. G., Epstein, M., Poythress, N. & Edens, J. F. Protecting people who decline to participate in research: an example from a prison setting. IRB-Ethics Hum. Res. 34, 15 (2012).

Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restor. Dent. Endod. 42, 152–155 (2017).

Haddad, A. End-of-life decisions: the family’s role. RN 67, 25–28 (2004).

Allmark, P. & Mason, S. Improving the quality of consent to randomised controlled trials by using continuous consent and clinician training in the consent process. J. Med. Ethics 32, 439–443 (2006).

Nelson, D. K. et al. Obtaining consent from both parents for pediatric research: what does “reasonably available” mean? Pediatrics 131, e223–e229 (2013).

Brandt, A. M. Racism and research: the case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Hastings Cent. Rep. 8, 21–29 (1978).

Freimuth, V. S. et al. African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 52, 797–808 (2001).

Lebet, R., Fineman, L. D., Faustino, E. V. S. & Curley, M. A. Q. Asking for parents’ permission to enroll their child into a clinical trial: best practices. Am. J. Crit. Care 22, 351–356 (2013).

Sheidow, A. J., Henry, D. B., Tolan, P. H. & Strachan, M. K. The role of stress exposure and family functioning in internalizing outcomes of urban families. J. Child Fam. Stud. 23, 1351–1365 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Daniela Santos for translating the surveys into Spanish and for enrolling patients in the study. We would also like to thank Marissa Garcia, Tate Closson-Niese, Amira Herstic, and Kayla Bell for enrolling patients into this study. Additionally, this study could not have been conducted without the help of Mimi Goodwin and Kathleen Grice. There was no external funding for this manuscript and all authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.L.M. conceptualized and designed the study and data collection instruments, collected data, and initiated and revised the manuscript. R.D.M. and R.D.C. conceptualized and designed the study and data collection instruments, supervised the study, reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, and revised the manuscript. R.D.M. provided final approval of the version to be published. L.B. conceptualized the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript. L.P. and J.L. made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data and helped to revise critical manuscript content. All authors are in agreement with the content of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent statement

Consent was provided through the completion of the survey.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, R.L., Comstock, R.D., Pierpoint, L. et al. Facilitators and barriers for parental consent to pediatric emergency research. Pediatr Res 91, 1156–1162 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01600-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01600-9