Abstract

Background

Given the high prevalence and complication risks of acid gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) in the first months of life in infants with esophageal atresia, the ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN consensus statement recommends systematic treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) until the age of 1 year and checking for acid GERD thereafter. However, these recommendations have not been evaluated.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted from 2007 to 2016. We evaluated the prevalence of acid GERD in 100 consecutive infants presenting with esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula after the age of 18 months when PPI treatment was stopped. The diagnosis of acid GERD was based on positive pH-metry and/or evidence of complications (e.g., peptic esophagitis, need for jejunal nutrition, or antireflux surgery). Those with acid GERD at a median age of 18 months received a control examination every year or adapted to their clinical situation.

Results

The prevalence rates of acid GERD were 64.3% at 18 months and 22.8% at the last follow-up (median age 65 months).There is no risk factor for acid GERD identified.

Conclusions

This study shows a high prevalence of acid GERD in late infancy and supports the recommendation of systematic checking for acid GERD when treatment with PPI is stopped.

Impact

-

Acid gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a frequent complication of esophageal atresia in infants. The ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN consensus, which is based on expert opinion, recommends systematic treatment of children with PPI until the age of 1 year.

-

The prevalence rates of acid GERD were 64.3% at 18 months and 22.8% at the last follow-up. This study shows a high prevalence of acid GERD in late infancy and supports the recommendation of systematic checking for acid GERD when treatment with PPI is stopped.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal atresia (EA) is a congenital malformation of the upper intestinal tract that has a prevalence of 1.97 per 10,000 births in France1 and between 1.77 and 3.68 per 10,000 births in 18 birth defect surveillance programs in the world.2 Although most children survive after initial reconstructive surgery, complications are common.3 Short-term complications seem to be related to prematurity, low birth weight, and associated malformations, especially cardiac malformations. The medium- and long-term morbidity is dominated by two types of complications: respiratory, mainly during the first years of life, and digestive in the short and long term, in particular when related to acid gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).4,5

In the general population, the prevalence of regurgitations peaks in infancy and become rare after the age of 2 years (24.4% of regurgitations in infants, 7.2% in children aged 2–11 years in the French cohort of 2012).6 By contrast, patients operated at birth for EA seem to have long-term persistent acid GERD.5

Acid GERD is considered to be a risk factor for complications, including anastomotic stricture,7 eating difficulties or undernutrition,5 esophagitis,8,9 and Barrett esophagus.10,11 Systematically treating children at birth is hypothesized to reduce the risk of these complications.12

As early as in 2008, a national protocol for the diagnosis and care of EA in France was initiated. This protocol recommended routine treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for all infants receiving surgery for EA until the age of 1.5 years and followed by a pH-metry monitoring after the cessation of PPI treatment during the second year of life to assess the persistence of acid GERD.13 More recently, an European and North American Societies for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition consensus has been reported that is similar to the recommended systematic treatment for 1 year and endoscopy or pH-impedancemetry monitoring after cessation of treatment.14

These recommendations are based on the presence of long-term persistent acid GERD with a greater risk of complications.

These recommendations, the persistence of acid GERD after 1 year of age, and the factors associated with persistence have not been evaluated. Therefore, we aimed to describe the prevalence and outcome of acid GERD in a cohort of infants with EA who were treated systematically with PPI and prospectively followed a maximum of 10 years. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of acid GERD at age 1.5 years. The secondary objectives were to identify predictive factors and those associated with acid GERD in late infancy and to assess the outcome of acid GERD and its associated factors at the follow-up.

Patients and methods

This prospective study was conducted from January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2016 in the French Reference Center for Congenital Abnormalities of the Esophagus, where all children born with EA/trachea–esophageal fistula (type III or IV EA according to Ladd classification15) were included in this study. We excluded pure EA patients since they are often long gap with delay in anastomosis and more complicated outcome.16 Data were collected from a population-based registry of EA, which began collecting data prospectively on all infants born with EA in France from January 1, 2007. The registry was approved by the National Informatics and Privacy Committee and was qualified by the National Committee of Register. All data were used anonymously, and the parents were informed of the aims of the registry.

Patients who were lost to follow-up before 18 months of age were excluded (Fig. 1). Following the national protocol, all patients were systematically treated orally with a PPI (esomeprazole 1 mg/kg/day) until a median age of 18 months (quartile 1 [Q1], 18; Q3, 20 months). The persistence of GERD was evaluated by 24-h pH-metry at least 5 days after cessation of PPI treatment. PPI treatment was gradually reduced, by 50% for 2 weeks then stopped 5 days before pH-metry.

The data were collected prospectively and included the following:

Neonatal characteristics included sex, prematurity, birth weight, type of atresia, associated malformations (cardiac, renal, anorectal, laryngeal cleft, limb, vertebral), and vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities disorder, which was defined as the presence of at least three of the following malformations: vertebral, anorectal, cardiac, esophageal, renal, or limb.

Surgical variables included anastomotic tension (subjectively assessed by the surgeon at the time of anastomosis), delayed surgery (>15 days after birth),17 and early complications (i.e., mediastinitis, anastomotic leakage). There is indeed no consensual definition of delayed surgery in literature. Delayed anastomosis was defined, following our previous papers, by an inability to perform end-to-end anastomosis within the first 15 days of life for anatomical reasons (excluding reasons such as extreme prematurity or severe cardiac malformation).

Outcomes included esophageal stenosis, esophageal dilatation, respiratory complications, signs of acid GERD, nutritional status, feeding mode (oral or enteral nutrition), and gastrostomy. Undernutrition was defined as a weight-for-height z score <2 standard deviations (SDs) below average. Small for gestational age was defined by birth weight <5th percentile for gestational age and sex (on anthropometric population curve), using the Audipog database. Pneumonitis was defined on a combination of clinical and radiological signs by a pediatric pulmonologist.

Acid GERD was assessed using a 24-h pH-metry recording. Positive pH-metry was defined as a reflux index > 7% (the time spent with pH < 4 over the total recording time).18 Meal period were not excluded during calculation of acid reflux index. Few patients had pH-impedancemetry, but we did not collect this information given the low number of cases and difficulties for analyzing impedance, which is low in EA patients. Acid GERD was defined as a positive pH-metry and/or evidence of complicated acid GERD, as defined as peptic esophagitis (macroscopic esophagitis with rupture of the esophageal mucosa) at endoscopy or the need for fundoplication or jejunal feeding. To define peptic esophagitis at endoscopy, eosinophilic esophagitis was eliminated in all patients (4–6 esophageal biopsies at 2–3 different levels) and histological esophagitis was not considered because its significance remains controversial.18 When persistent acid GERD was found, PPIs were restarted at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day. We analyzed only those children whose acid GERD evaluation was performed using pH-metry and/or endoscopy (Fig. 1).

In patients whose acid GERD was documented at age 18 months, a control examination was performed at least 1 year later and was repeated every year until the child exhibited negative pH-metry. The last follow-up was defined according to the characteristics of the patients at the last follow-up consultation and the results of the last pH-metry. The median age at the last follow-up was 65 months (Q1, 40; Q3, 85 months).

The secondary objectives were to evaluate the following factors.

-

Predictive factors of acid GERD at 18 months: factors appearing since birth and surgical characteristics that predicted acid GERD at 18 months.

-

Factors associated with acid GERD at age 18 months: other factors or complications occurring after the surgery during the follow-up.

-

The prevalence of persistent acid GERD at the last follow-up. Persistent acid GERD was defined as positive pH-metry or acid GERD complications at the last follow-up in a child who exhibited acid GERD at the first evaluation. Patients with an acid GERD at the first evaluation who had received antireflux surgery after 36 months were excluded from this analysis.

-

Factors that predicted and were associated with persistent acid GERD at the last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as median and interquartile range and categorical variables as numbers (percentages). The time of acid GERD disappearance after the monitoring process was described as a censored variable taking into account the use of a Nissen procedure as competing event; cumulative incidence of acid GERD disappearance was estimated using the Kalbfleisch and Prentice method.19 Bivariate analyses of factors associated with acid GERD at 18–36 months and at the last follow-up were performed using chi-square test (or Fisher’s test when expected cell frequency <5) for categorical variables and using Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative variables. No statistical comparisons were done for categorical variables with frequency <5. Statistical testing was conducted at the two-tailed α level of 0.05. Data were analyzed using the SAS software package, release 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

One hundred children with EA/trachea–esophageal fistula were born between January 2007 and December 2016 and were operated on in our center. Five patients were lost to follow-up. Children who underwent antireflux surgery before 18 months of age (n = 5) or who did not have an acid GERD evaluation (n = 20) were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1).

The main characteristics, including age, prematurity, birth weight, and surgical variables, did not differ significantly between the 25 patients not included in the study and the 70 who were included (Supplemental digital content, Table 1).

Seventy patients were included in the final analysis; 52 (74.3%) were boys, and the median birth weight was 2830 g (interquartile range 2380–3150 g). Twenty-six (37.7%) children were born prematurely. Sixty-eight patients (97.1%) had type III EA and 2 (2.9%) had type IV EA. The characteristics of the population included in the final analysis are shown in Table 1.

At first evaluation, among the 70 patients included in the analysis, 60 (86%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 78–94) had endoscopy, 63 (90%, CI 83–97) had a pH-metry, and 37 (53%, CI 41–65) had both evaluations. The prevalence of acid GERD at 18 months was 64.3% (CI 53–75.5); 48.6% (CI 36.4–60.8) had positive pH-metry and 22.9% (CI 13.7–34.4) had complicated acid GERD, including 6 patients with peptic esophagitis. None of these infants had eosinophilic esophagitis.

At the first evaluation, the patients’ median weight was 10.3 kg (interquartile range 9.2–11 kg) and median age was 18 months (interquartile range 18–20 months). The first pH-metry was performed at a median age of 25 months (interquartile range 20–30 months). Thirty-eight (55.9%) patients presented with dysphagia for solids. Thirty-one (44.3%) children presented with esophageal anastomotic stenosis, 11 patients (36.7% of esophageal stenosis) with recurrent stenosis (>3 esophageal dilatations), and 3 (10% of esophageal stenosis) with recalcitrant stenosis (>5 esophageal dilatations). Dysphagia was defined as difficulty of swallowing solids or mixed food as reported by parents. Most often, these children had an endoscopy (41/50, 82%). The clinical characteristics of the children at the time of the evaluation are shown in Table 2.

Seven children who had positive pH-metry also had peptic esophagitis identified by endoscopy. Of the 37 patients who had pH-metry and endoscopy, 19 (51%, CI 35–67) had positive pH-metry without esophagitis, and no patient had negative pH-metry with esophagitis. Median reflux index was 17.6 (Q1 10.4; Q3 23.2) (Table 3). Twenty (28.6%) children who did not have any digestive symptoms (dysphagia, regurgitation, vomiting) presented with acid GERD.

There was no factor that significantly predicted the presentation of acid GERD at 18 months of age. The surgical characteristics did not differ between groups (Table 4).

The prevalence of persistent acid GERD at the last follow-up in those who had acid GERD at 18 months was 22.8% (CI 12.7–35.8). Their median weight was 17.8 kg (interquartile range: 16–21.7 kg) and median age was 5.4 years (interquartile range: 3.3–7 years) at the last consultation. The last pH-metry was performed at a median age of 32 months (interquartile range: 25–43 months). Complicated acid GERD was observed in 7% (CI 0.2–17.0%) of patients and acid GERD was observed at the time of pH-metry in 19.3% (CI 10.0–31.9%) of patients.

When looking at the difference in acid GERD at 1.5 years and at follow-up, we did not find any difference between premature and at term infants: 53 versus 56% (p = 0.94) at 1.5 years, 26 versus 42% (p = 0.49).

There is no factor that significantly predicted persistent acid GERD at the last follow-up (Table 4), and no factor associated with persistent acid GERD at the last follow-up (Table 5).

There is no association between respiratory symptoms and presence of esophagitis or a positive pH-metry at 1.5 year and at the last follow-up (Table 6).

When looking at the difference in digestive symptoms at 1.5 years and at the last follow-up, there was a significative difference between the presence and absence of esophagitis at 1.5 years, 85.7 versus 19.2% (p = 0.001), but not at the last follow-up. There was no association between digestive symptoms and positive pH-metry at 1.5 years and at the last follow-up. When looking at the difference between positive pH-metry and at 1.5 years, there was no significative difference between the presence and absence of esophagitis at 1.5 years, 100 versus 36% (p = 0.056).

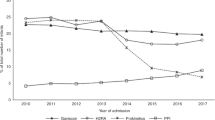

The probability that acid GERD disappeared over time in children with an acid GERD at the age of 18 months increased regularly to 62% at age 46 months and remained constant at 72% after 80 months (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In this study, we found a high prevalence of acid GERD; about two-thirds of infants who had received an operation for EA/tracheoesophageal fistula exhibited acid GERD during late infancy, and this decreased to about one-fourth at age of 6 years. This confirms data from previous studies using different definitions of acid GERD. The prevalence of acid GERD was reported as 43% in Canadian EA patients with a median age of 5 years and 4 months.20 In that study, acid GERD was defined as the presence of moderate-to-severe esophagitis at biopsy, intestinal metaplasia, the need for fundoplication, or need for jejunal feeding, or some combination. This definition is similar to our “complicated” acid GERD, except we did not consider esophagitis at histology as its significance remains controversial. They did not consider pH-metry in their study. Another study of 32 patients with EA used pH-metry and reported that >45% of patients exhibited acid GERD21 at a median age of 15 months. A recent study in the Netherlands found lower prevalence rates of 10% for abnormal pH/impedance in infants (aged <18 months) and 12.5% in older children. This study included a small population (50 infants and 74 children) and included only 48% of eligible infants and 5.9% of eligible children.22

Our study is one of only few longitudinal studies to have examined the evolution of acid GERD over time.23 Our longitudinal study with repeated examination at the follow-up shows the importance of monitoring acid GERD in infants and children with EA. Moreover, we could not identify any risk factors for the persistence of acid GERD that could help in targeting the control examination to a specific high-risk group of children. The prevalence of acid GERD decreased gradually from age 1.5 to 4 years, but it seemed to plateau and remain high after 4 years; that is, 40% of children with acid GERD at 18 months exhibited persistent acid GERD at age 4 years. A longitudinal study of 60 patients with EA performed in the United States found prevalence rates of acid GERD of 48% at age 5 years, 25% at 5–10 years, and 31% after age 10 years.8 This change with age has also been reported by another study.24 A recent prospective study of 73 EA patients during 11 years reported that PPI treatment could be discontinued in 48% of patients at age 2.4 years.23 Our results are consistent with these previous studies and highlight the importance of long-term follow-up and repeated acid GERD examination in EA patients.

Another important finding of our study is that acid GERD can persist without any specific digestive symptoms; that is, >25% of our children with positive pH-metry had no regurgitation, dysphagia, or vomiting. Several reasons may explain this finding, including the possibility that children with EA may cope with their symptoms and not report them or may have lower esophageal mucosa sensitivity or esophageal dysmotility, which may mask acid GERD symptoms.5,25,26 The high rate of acid GERD complications reported in children with EA (mainly esophagitis, gastric metaplasia, and even Barrett esophagus)11,27 reinforces our belief that systematic monitoring of acid GERD should be performed in EA patients after PPI cessation.

The results show an association between digestive signs and the presence of esophagitis, but not with a positive pH-metry. Indeed, the digestive signs sought were dysphagia, regurgitation, and vomiting, which are not specific of acid GERD, but possibly explained by esophageal stenosis or esophagitis or dysmotility. It is difficult at this age to assess the presence of heartburn. Despite this result, it therefore seems important to realize the pH-metry because the clinical diagnosis of acid GERD may be difficult based on symptoms in this context.

This study did not find any improvement over time in pneumonitis (Table 2). Respiratory complications have been shown to be very frequent during infancy28 and results from several mechanisms, including acid GERD, tracheomalacia, aspiration, and recurrence of fistula.29 Another interesting finding is the increase of the number of recalcitrant strictures with age. This is probably due to the longer follow-up but not to eosinophilic esophagitis since it was ruled out in all of our patients.

The benefits of systematically treating every EA patient with PPI from birth to the age of 1 year or even longer are debated. Although PPI treatment is well tolerated, prolonged treatment is associated with the risk of gastroenteritis, Clostridium difficile colitis, and lung infection.27,30,31,32 The benefits of using PPI to prevent anastomotic stenosis have been discussed.23,33 Although we could not answer this question in our study, in which we systematically treated patients from birth, our data show clearly that continuing to monitor for acid GERD after 1 year of age allowed nearly 50% of children to stop PPI treatment by the age of 2.9 years. However, we also found that >20% of children with EA will still need prolonged PPI treatment until age 4 or 6 years. It may therefore be important to reassess the need for treatment and the persistence of acid GERD to limit its use for persistent acid GERD.

Our study has some limitations. We studied only children with acid reflux, so we probably underestimated the incidence of acid GERD. A recent study using pH/impedancemetry showed 52% nonacid retrograde bolus movement in children with EA.22 Impedance monitoring is a more recently introduced analysis, and the results are difficult to interpret for children with EA because of the esophageal dysmotility and low impedance accompanying this pathology. In our population, few patients had pH/impedancemetry, we were therefore unable to analyze this information. Our study also experienced a loss of data because of the 20 patients who, for various reasons, did not have acid GERD evaluation (no pH-metry or fibroscopy). Another limitation is that not all patients had both pH-metry and endoscopy, which may have underestimated the prevalence of acid GERD as there can be poor correlation between the results of these investigations.

The strengths of our study are its prospective design and the collection of data in a reference center for EA, which increased the quality of data and limited the rate of missing data.

Conclusion

This study strongly supports the recommendation to check systematically for acid GERD after the age of 1 year in all infants born with EA/tracheoesophageal fistula, even if the patient does not present with any specific digestive symptoms. To prevent complications, long-term follow-up of these children by specialized multidisciplinary clinics should include pH-metry and/or endoscopy.

References

Sfeir, R., Michaud, L., Salleron, J. & Gottrand, F. Epidemiology of esophageal atresia. Dis. Esophagus 26, 354–355 (2013).

Nassar, N. et al. Prevalence of esophageal atresia among 18 international birth defects surveillance programs. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 94, 893–899 (2012).

Goyal, A., Jones, M. O., Couriel, J. M. & Losty, P. D. Oesophageal atresia and tracheo-oesophageal fistula. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 91, F381–F384 (2006).

Montgomery, M. & Frenckner, B. Esophageal atresia: mortality and complications related to gastroesophageal reflux. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 3, 335–338 (1993).

Legrand, C. et al. Long-term outcome of children with oesophageal atresia type III. Arch. Dis. Child. 97, 808–811 (2012).

Martigne, L. et al. Prevalence and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children and adolescents: a nationwide cross-sectional observational study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 171, 1767–1773 (2012).

Deurloo, J. A., Ekkelkamp, S., Schoorl, M., Heij, H. A. & Aronson, D. C. Esophageal atresia: historical evolution of management and results in 371 patients. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 73, 267–272 (2002).

Little, D. C. et al. Long-term analysis of children with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. J. Pediatr. Surg. 38, 852–856 (2003).

Somppi, E. et al. Outcome of patients operated on for esophageal atresia: 30 years’ experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 33, 1341–1346 (1998).

Hameeteman, W., Tytgat, G. N., Houthoff, H. J. & van den Tweel, J. G. Barrett’s esophagus: development of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 96, 1249–1256 (1989).

Schneider, A. et al. Prevalence of Barrett esophagus in adolescents and young adults with esophageal atresia. Ann. Surg. 264, 1004–1008 (2016).

Shawyer, A. C., Pemberton, J., Kanters, D., Alnaqi, A. A. A. & Flageole, H. Quality of reporting of the literature on gastrointestinal reflux after repair of esophageal atresia-tracheoesophageal fistula. J. Pediatr. Surg. 50, 1099–1103 (2015).

Centre de référence des affections chroniques et malformatives de l'oesophage (CRACMO) et Filière nationale des maladies rares abdominothoraciques (FIMATHO), Protocole Nationale de Diagnostic et de Soins, Atrésie de l'oesophage, 2018. Available from: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2018-12/20181212_pnds_atresie_de_loesophage_dec_2018_vf_charte.pdf.

Krishnan, U. et al. ESPGHAN-NASPGHAN Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Complications in Children With Esophageal Atresia-Tracheoesophageal Fistula. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 63, 550–570 (2016).

Ladd, W. E., Swenson, O. & Esophageal Atresia and tracheo-esophageal fistula. Ann. Surg. 125, 23–40 (1947).

Dingemann, C. et al. ERNICA Consensus Conference on the Management of Patients with Long-Gap Esophageal Atresia: Perioperative, Surgical, and Long-Term Management. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 30, 326–336 (2020).

François, B. et al. Predictors of the performance of early antireflux surgery in esophageal atresia. J. Pediatr. 211, 120.e1–125.e1 (2019).

Vandenplas, Y. et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 49, 498–547 (2009).

Prentice, R. L. et al. The analysis of failure times in the presence of competing risks. Biometrics 34, 541–554 (1978).

Castilloux, J., Noble, A. J. & Faure, C. Risk factors for short- and long-term morbidity in children with esophageal atresia. J. Pediatr. 156, 755–760 (2010).

Catalano, P., Di Pace, M. R., Caruso, A. M., Casuccio, A. & De Grazia, E. Gastroesophageal reflux in young children treated for esophageal atresia: evaluation with pH-multichannel intraluminal impedance. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 52, 686–690 (2011).

Vergouwe, F. W. T. et al. Evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux in children born with esophageal atresia using pH and impedance monitoring. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 69, 515–522 (2019).

Righini Grunder, F. et al. Should proton pump inhibitors be systematically prescribed in patients with esophageal atresia after surgical repair? J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 69, 45–51 (2019).

Koivusalo, A., Pakarinen, M. P. & Rintala, R. J. The cumulative incidence of significant gastrooesophageal reflux in patients with oesophageal atresia with a distal fistula-a systematic clinical, pH-metric, and endoscopic follow-up study. J. Pediatr. Surg. 42, 370–374 (2007).

Nakazato, Y., Landing, B. H. & Wells, T. R. Abnormal Auerbach plexus in the esophagus and stomach of patients with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. J. Pediatr. Surg. 21, 831–837 (1986).

Gottrand, M., Michaud, L., Sfeir, R. & Gottrand, F. Motility, digestive and nutritional problems in esophageal atresia. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 19, 28–33 (2016).

Bardou, M., Fortinsky, K. J., Chapelle, N., Luu, M. & Barkun, A. An update on the latest chemical therapies for reflux esophagitis in children. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 20, 231–239 (2019).

Schneider, A. et al. Results from the French National Esophageal Atresia register: one-year outcome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 9, 206 (2014).

Koumbourlis, A. C. et al. Care recommendations for the respiratory complications of esophageal atresia-tracheoesophageal fistula. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 55, 2713–2729 (2020).

Chang, T.-H. et al. Increased age and proton pump inhibitors are associated with severe Clostridium difficile infections in children. J. Microbiol Immunol. Infect. 53, 578–584 (2020).

Poddar, U. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in children. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 39, 7–12 (2019).

De Bruyne, P. & Ito, S. Toxicity of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors in children. Arch. Dis. Child. 103, 78–82 (2018).

Miyake, H. et al. Are prophylactic anti-reflux medications effective after esophageal atresia repair? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 34, 491–497 (2018).

Acknowledgements

In memory of Dr. L Michaud, who inspired this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.F. and F.G. contributed to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and final approval of the version to be published. M.A. contributed to conception and design and final approval of the version to be published. D.L., R.S., A.N., and M.B. contributed to final approval of the version to be published. A.D. contributed to analysis and interpretation of data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent statement

Data were collected from a population-based registry of esophageal atresia, which began collecting data prospectively on all infants born with esophageal atresia in France from January 1, 2007. The registry was approved by the National Informatics and Privacy Committee and was qualified by the National Committee of Register. All data were used anonymously, and the parents were informed of the aims of the registry.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flatrès, C., Aumar, M., Ley, D. et al. Prevalence of acid gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants with esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula. Pediatr Res 91, 977–983 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01510-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01510-w

This article is cited by

-

Endoscopic management of esophageal mucosal bridges in children with esophageal atresia

Surgical Endoscopy (2023)