Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between race and severe neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS) in infants exposed to intrauterine opioids.

Methods

This is a prospective observational study on intrauterine opioid-exposed term infants. Exposure to opioids was based on maternal disclosure, urine, or umbilical cord drug screening. Severe NOWS was defined based on modified Finnegan scoring and the need for pharmacological intervention.

Results

One hundred and fifty mother–infant pairs, 60 Black and 90 White with history of opioid exposure during pregnancy, were included. More White than Black infants developed NOWS that required pharmacological treatment, 70 vs. 40%: RR = 1.75 (1.25–2.45). In adjusted analysis, there was no significant association between race and the development of severe NOWS in mothers who attended opioid maintenance treatment program (OMTP). However, in mothers who did not attend OMTP, White race remained a significant factor associated with the development of severe NAS, RR = 1.69 (1.06, 2.69).

Conclusions

Severe NOWS that required pharmacological intervention was significantly higher in White than in Black infants born to mothers who did not attend OMTP. Larger studies are needed to evaluate the association between social as well as genetic factors and the development of NOWS.

Impact

-

There is a significant association between race and development of severe NOWS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of opioid use/abuse during pregnancy and therefore the number of intrauterine opioid-exposed infants has increased significantly over the past decades.1,2,3 About 50–94% of opioid-exposed infants show varying manifestations of withdrawal that include autonomic and central nervous system dysfunction and respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders.3 Among those who show withdrawal signs, 30–80% require pharmacological interventions.1

Several factors have been identified to be associated with neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS): intrauterine exposure to opioids; attendance to opioid maintenance treatment program (OMTP) for opioid use disorder (OUD);4 and concomitant use of opioids with other substances, such as methamphetamine,5 cocaine,6 marijuana,7 tobacco,8 and psychotropic medications.9 Also, other factors such as maternal psychological disorders and socioeconomic disparity,10 genetic polymorphism for metabolism of drugs in mothers and infants,11 genomic variants for placental absorption, metabolism and distribution of drugs,12 term infants compared to preterm infants,13 and male sex.14 have been entertained as possible reasons for manifestation of severe NOWS. Although opioid use and OUD are more commonly observed in White mothers, there is still a paucity of information on the significance of racial association and the development of NOWS. In general, the severity of NOWS is believed to be multifactorial.2,4,9,10,13,14,15

Like many centers, we also observed an increase in the number of mothers with OUD over the past several years and as a result an increased number of infants who required to be admitted for close observation and/or treatment for opioid withdrawal. While most of our obstetric population were Black, we noticed that many of our infants with severe NOWS who required pharmacological interventions were White. A plausible thought was that we might have had more White than Black mothers with OUD in our Maternity Ward, Black mothers had less access to OMTP, or White infants were more prone for severe NOWS.

We hypothesized that race is associated with the development of severe NOWS. In order to validate our hypothesis, we followed mothers who used/abused opioids during pregnancy and collected outcome data on their infants with specific attention to racial differences.

Methods

This is a single-center prospective observational study at the Regional One Health (ROH) Hospital, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) in Memphis, TN. Our maternity hospital at ROH is a regional medical center that provides services to high-risk pregnancy and low-income mothers.

For this study, data were collected from the ongoing OUD/NOWS project in our institution (July 2013 to December 2017). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC). As per OUD/NOWS project, informed consent was obtained from the mothers or the legal guardians within 24–36 h of delivery. All infants exposed to intrauterine opioids were eligible for this study. Opioid exposure was based on maternal disclosure to opioid use during this pregnancy, positive opioids in maternal and/or infant’s urine, and/or the umbilical cord drug screening. All mothers with OUD were referred to an OMTP. Those who attended the program were prescribed methadone or buprenorphine and received counseling.

As per the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations and our NICU guidelines, all newborns with prenatal history of opioid exposure were admitted for 5–7 days of observation or for a longer duration if treatment for withdrawal was needed.3 In 2006, our NICU developed internal guidelines for the management of NOWS; no changes to the guidelines were made during study period. All opioid-exposed infants received supportive care such as on-demand high-calorie formula,16 a quiet environment, swaddling, cuddling, rocking, music, and/or massage therapy throughout their NICU stay.17 A recent practice for infants born to mothers with OUD encourages the “Eat, Sleep, Console” method, breast feeding, and rooming-in in order for mothers to bond with their infants, to reduce the pharmacological intervention, and to decrease the duration of hospital stay.18 Since we were not equipped to monitor the maternal drug use during infant’s hospital stay, no breast feeding was recommended, and no rooming-in was provided. However, we encouraged parents and immediate designated family members to visit and stay with the infants as long and as often as their lifestyle allows.19

In order to assess the severity of opioid withdrawal in infants, several scoring methods have been developed over the years.3 We chose the modified Finnegan scoring method that is widely used for evaluation of infants exposed to intrauterine opioids.3 This modified scoring system includes 31 items that evaluate signs of central nervous system, metabolic, vasomotor, respiratory, and gastrointestinal disturbances. Items are scored numerically from 1 to 5 depending on the severity of clinical signs. The modified Finnegan scoring was performed every 4 h. This method considers three consecutive scoring of ≥8 as severe NOWS.3 This is a valid cut-off, since in a prospective study, well infants who were not exposed to intrauterine opioids had Finnegan scoring of <8 during the first 3 days of life and again during the weeks 5 and 6.20 Pharmacotherapy was initiated when 3 consecutive scorings were ≥8 or 2 consecutive scorings were ≥12. Infants who required pharmacotherapy were grouped as “severe NOWS.” Infants requiring no pharmacotherapy were grouped as “no/mild NOWS.” Morphine was our first drug of choice, and phenobarbital was an adjunct drug for the management of the withdrawal.3 Our nurses were trained to use the modified Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System. The study by Kushnir et al.21 showed that the time of the day or the day of the week did not influence the reliability of Finnegan scoring obtained by nurses.

Statistics

SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute Cary, NC) was used for the statistical evaluation. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the continuous variables between the two race groups. All tests were two sided; p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± SD and/or as median and interquartile range as appropriate. A simple univariate analysis was initially run between the severe NOWS and non-severe/no-NOWS groups on all clinical variables. Binomial regression with PROC GENMOD was used derive relative risks; a 95% confidence interval was calculated for each test. When p < 0.1, effect modification and confounding among variables were evaluated before progressing with the model. Results are presented stratified by the different levels of the variable to show the direction and magnitude of the association.

Results

During the study period, 243 infants were exposed to intrauterine opioids. Ninety-three infants were preterm and were excluded since Finnegan scoring system is designed for evaluation of term infants. Data were collected from the remaining 150 mother–infant pairs. Ninety-nine percent of mothers with OUD were low income and were enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid Program (TN-CARE Insurance). Sixty mothers (40%) identified themselves as Black. Table 1 represents the characteristics of all mothers with OUD and their infants stratified by race. Black mothers had a significantly higher parity at the time of delivery. They were also significantly more likely to have used tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and to have a urine drug screen positive for opiates. White mothers were significantly more likely to have attended an OMTP; however, there was no racial difference in the relative frequency of prescription of methadone or buprenorphine while attending the program.

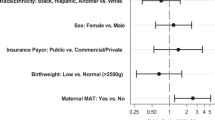

Table 2 represents univariate analysis for variables associated with the development of severe NOWS. Factors that were significantly different between the races (use of THC, maternal parity, and a positive maternal urine drug screen) did not significantly modify the association between race and the development of severe NOWS. In a stratified analysis, 50 mothers used THC. Racial difference in the development of severe NOWS was not influenced by concomitant use of THC. The risk ratio (RR) for White infants for the development of severe NOWS in mothers who used THC was 1.72 (1.08, 2.73) as compared to 1.92 (1.18, 3.12) in infants whose mothers did not use THC. A hundred mothers had a parity at ≤2. In this group, White race had an RR of 1.87 (1.14, 3.07) for the development of severe NOWS as compared with mothers with a parity >2, RR = 1.73 (1.07, 2.80). Of the 127 mothers who had a UDS test done, 16 were negative and 111 were positive for opiates. In the positive group, the RR for White race for the development of severe NOWS was 1.67 (1.18, 2.36).

In the adjusted analysis between the two significant variables of White race and attendance to OMTP, both variables remained significantly associated with the development of severe NOWS. White race had an RR of 1.51 (1.06, 2.16), and attendance to OMTP had an RR of 1.44 (1.08, 1.93). There was no interaction between the two variable, p = 0.92. Black mothers attending OMTP only comprised 19% of the attendees. In the adjusted analysis, there was no association between race and the development of severe NOWS in infants who were born to mothers who attended OMTP; only 6 infants with severe NOWS were Black. There was also no racial difference between mothers taking methadone and the development of severe NOWS, Table 3. However, in mothers who did not attend OMTP, White race remained a significant factor associated with the development of severe neonatal abstinence syndrome, RR = 1.69 (1.06, 2.69).

Discussion

In this prospective observational study, we found that White infants with exposure to intrauterine opioids had significantly more severe NOWS that required pharmacological interventions compared to Black infants.

While several factors have been reported to be associated with the development of NOWS, race has not been commonly found to be an independent factor associated with the development of severe NOWS.9,10,13,14 Also, a significant number of studies were on White mothers who attended the methadone/buprenorphine treatment program.9,10,13,14 Up to 80% of infants prenatally exposed to methadone/buprenorphine develop NOWS, and the severity of withdrawal is not believed to be related to methadone dosage.6,22,23,24

Socioeconomic status and racial disparity in health care of mothers with OUD are among factors that may contribute to NOWS. Although 80% of our obstetric population were Black and 10% were White (10% were other racial group), the racial distribution of our mothers with OUD was 60% White and 40% Black. Our study population was unique since both Black and White mothers with OUD were socially and economically disadvantaged. They were unemployed and had TN-CARE Insurance (Medicaid). Our Black mothers had higher parity, higher THC and cocaine abuse, and higher positive urine drug screen compared to the White mothers. Our White mothers had more psychiatric disorders but attended OMTP more often than the Black mothers. Although all mothers were referred to OMTP by their Obstetricians, only 45% (67/150) attended the OMTP (63% of White and 22% of Black mothers). Not attending the OMTP was likely due to the economic barriers, since many treatment programs only accept cash payments, and only 20% may accept patients with Medicaid insurance.25 It seems that some White mothers had more family support in order to afford the OMTP than most Black mothers.

Our Black mothers used THC more often than White mothers. We speculate that, by using THC, they may have used less opioids. Endogenous cannabinoid receptors and opioid receptors are co-distributed in the peripheral and the central nervous system, and both are involved in providing analgesia and drug rewards.26 THC is involved in the release of endogenous opioids. In a clinical study, when cannabinoids and opioids were co-administered, they produced synergistic pain relief in adults.27 Some studies do suggest the use of medical cannabis as a treatment for OUD.28 However, there are no reports on the effects of maternal combined opioids and THC use and the frequency of NOWS.

Although cocaine use was only 16% among our mothers with OUD (24/150), Black mothers used cocaine twice as often as White mothers. It is known that Black women more frequently use cocaine.29 Cocaine causes uterine and placental vasoconstriction.30 Thus cocaine and opioid co-abuse can potentially result in less opioids crossing the placenta and reaching the fetus. This may be associated with a lower incidence of severe NOWS in Black infants.

There are limited publications that associate race with NOWS. A retrospective study from the largest nationwide Pediatric database (KID 2016) using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic codes showed that >80% of infants with NOWS were of White race.2 However, it was not clear whether these infants required pharmacological intervention, supportive care, or no specific care, or the ICD code was just based on the maternal history of opioid use.2 Also, in a retrospective case–control study on infants who developed signs of withdrawal (NOWS), Parikh et al.31 reported that White infants were more likely than Black infants to receive pharmacotherapy (84 vs. 70%, respectively). In that study, there was no description of maternal racial distribution (Black and White) or the characteristics of mothers with OUD whose infants did not show withdrawal signs. Since not all infants prenatally exposed to opioids would display signs of withdrawal, this information would help to evaluate the strength of White race as a factor potentially associated with the development of severe NOWS.

Among infants with severe NOWS, only 25–30% may require prolonged duration of treatment with several drugs and prolonged length of hospital stay.3,11 In these cases, maternal, infant, and placental genetic and epigenetic profiles may help in prediction of severe NOWS. Several studies showed that genetic variants in opioid receptor genes, genes involved in metabolism of drugs, and the stress response genes may be the reason for severe withdrawal in some infants.11,32,33 Wachman et al.34 reported an association with both maternal and infant’s opioid gene variants [µ opioid receptor, catechol-O-methyl transferase, and prepronociceptin] and the severity of NOWS. Cole et al.35 showed that there are differences in racial/ethnic (European-American, African, and Latino) allele frequencies and associated single-nucleotide polymorphism in opioid receptor genes in neonates with NOWS phenotype

The study by Sadhasivam et al.36 showed that a large inter-individual variability exits in morphine pharmacokinetics that is believed to be due to genotype variants in organic cation transporter (OCT1). OCT1 is important for absorption, distribution, and elimination of morphine.37 Black children have 23% higher morphine clearance than White children.37 OCT1 transporter also involves in clearance of maternally acquired opioids. Lower clearance of opioids in Whites may result in prolonged exposure to opioids causing disruption of neuronal and glial maturation in the central nervous system of infants.38 Therefore, it may have an impact on long-term neurological outcome of infants with NOWS.38,39

Limitations and strengths of the study

There were several limitations to our study: (1) all scoring systems are subjective measures that can be influenced by the level of training and experience of the observer. Inter-observer variations in scoring may exist and the possibility of an unintentional bias in scoring cannot be ruled out;40 (2) We did not present separately infants who had no withdrawal from those who had mild withdrawal signs but did not require pharmacotherapy; (3) We also did not have data on the amount, route (IV, PO, smoking), frequency, and the duration of opioids, tobacco, marijuana, and other co-drug usage; (4) There were only 13 Black mothers who attended OMTP and only 6 of their infants developed NOWS. This may explain the absence of an association between race and severe OUD in infants born to mothers who attended OMTP; (5) Differences in management strategies in the OMTP; and (6) Unknown genetic status of mothers and infants.

The strengths of our study include: (1) its prospective nature; (2) similar socioeconomic status of our mothers (high poverty level), and (3) having data on infants who had no signs of withdrawal/mild withdrawal who did not require pharmacological interventions.

Conclusion

There is a significant association between race and development of severe NOWS. A prospective multicenter study with a large number of mothers with OUD and comparable racial distribution is needed to further delineate this association. Similar studies also are needed to study whether there are any racial differences on long-term neurodevelopmental outcome of intrauterine opioid-exposed infants.

References

Patrick, S. W., Davis, M. M., Lehman, C. U. & Cooper, W. O. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009-2012. J. Perinatol. 35, 650–655 (2015).

Ramphul, K., Gonzalez Mejias, S. & Joynauth, J. An update on the burden of neonatal abstinence syndrome in the United States. Hospital Pediatr. 10, 1–4 (2020).

Hudak, M. L., Tan, R. C., The Committee on Drugs & The Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics 129, e540–e560 (2012).

Tolia, V. N. et al. Antenatal methadone vs buprenorphine exposure and length of hospital stay in infants admitted to the intensive care unit with neonatal abstinence syndrome. J. Perinatol. 38, 75–79 (2018).

Smid, M. C., Metz, T. D. & Gordon, A. J. Stimulant use in pregnancy- an under-recognized epidemic among pregnant women. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 62, 168–184 (2019).

Malek, A., Obrist, C., Wenzinger, S. & von Mandach, U. The impact of cocaine and heroin on placental transfer of methadone. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 7, 1–9 (2009).

Volpe, J. J. Commentary-Marijuana use during pregnancy and premature birth: a problem likely to worsen. J. Neonatal Perinat. Med. 13, 1–3 (2020).

Jones, H. E. et al. Cigarette smoking in opioid-dependent pregnant women: neonatal and maternal outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 131, 271–277 (2013).

Wachman, E. M. et al. The relationship between maternal opioid agonists and psychiatric medications on length of hospitalization for neonatal abstinence syndrome. J. Addict. Med. 5, 293–299 (2011).

Benningfield, M. M. et al. Co-occurring psychiatric symptoms are associated with increased psychological, social, and medical impairment in opioid dependent pregnant women. Am. J. Addict. 19, 416–421 (2010).

Wachman, E. M. & Farrer, L. A. The genetics and epigenetics of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 24, 105–110 (2019).

Balyan, R. et al. CYP2D6 pharmacogenetic and oxycodone pharmacokinetics association study in pediatric surgical patients. Pharmacogenomics 18, 337–348 (2017).

Gibson, K. S., Stark, S., Kumar, D. & Bailit, J. L. The relationship between gestational age and the severity of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addiction 112, 711–716 (2016).

Holbrook, A. & Kaltenbach, K. Gender and NAS: does sex matter? Drug Alcohol Depend. 112, 156–159 (2010).

Patrick, S. W. et al. Prescription opioid epidemic and infant outcomes. Pediatrics 135, 842–850 (2015).

Bogen, D. L., Hanusa, B. H., Baker, R., Medoff-Cooper, B. & Cohlan, B. Randomized clinical trial of standard-versus high-calorie formula for methadone-exposed infants: a feasibility study. Hospital Pediatr. 8, 7–14 (2018).

Bagley, S. M., Wachman, E. M., Holland, E. & Brogly, S. B. Review of the assessment and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 9, 1–10 (2014).

Grossman, M. R. et al. An initiative to improve the quality of care of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics 139, e1–e7 (2017).

Howard, M. B. et al. Impact of parental presence at infants’ bedside on neonatal abstinence syndrome. Hospital Pediatr. 7, 63–69 (2017).

Zimmermann-Baer, U., Notzli, U., Rentsch, K. & Bucher, H. U. Finnegan neonatal abstinence scoring system: normal values for first 3 days and weeks 5-6 in non-addicted infants. Addiction 105, 524–528 (2010).

Kushnir, A., Bleznak, J. L., Saslow, J. G. & Stahl, G. Nurses’ Finnegan scoring of newborns with neonatal abstinence syndrome not affected by time or day of week. Am. J. Perinatol. 37, 224–230 (2020).

McCarthy, J. J. et al. The use of serum methadone/methadone ratios to monitor changing perinatal pharmacokinetics. J. Addict. Med. 12, 241–246 (2018).

Jansson, L. M., Velez, M. & Harrow, C. The opioid-exposed newborn: assessment and pharmacologic management. J. Opioid Manag. 5, 47–55 (2009).

McCarthy, J. J., Leamon, M. H., Parr, M. S. & Anania, B. High-dose methadone maintenance in pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 193, 606–610 (2005).

Patrick, S. W. et al. Association pf pregnancy and insurance status withtreatment access for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw. Open 3, 1–12 (2020).

Welch, S. P. Interaction of the cannabinoid and opioid systems in the modulation of nociception. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 21, 143–151 (2009).

Cooper, Z. D. et al. Impact of co-administration of oxycodone and smoked cannabis on analgesia and abuse liability. Neuropsychpharmacology 43, 2046–2055 (2018).

Lofwall, M. R., Babalonis, S., Nuzzo, P. A., Elay, S. C. & Walsh, S. L. Opioid withdrawal suppression efficacy of oral dronabinol in opioid depenent humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1, 164–50 (2016).

Chasnoff, I. J., Landress, H. J. & Barrett, M. E. The prevalence of illicit-drug or alcohol use during pregnancy and discrepencies in mandatory reporting in Pinellas County, Florida. N. Engl. J. Med. 322, 1202–1206 (1990).

Plessinger, M. A. & Woods, J. R. Maternal, placental, and fetal pathophysiology of cocaine exposure during pregnancy. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 36, 267–277 (1993).

Parikh, A., Gopalakrishnan, A. A., Booth, A. & El-Metwally, D. Racial association and pharmacotherapy in neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome. J. Perinatol. 39, 1370–1376 (2019).

Oei, J. L. et al. Dopamine D2 receptor gene polymorphisms in newborn infants of drug-using women. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 97, F193–F198 (2012).

Venkatasubramanian, R. et al. ABCC3 and OCT1 genotypes influence pharmacokinetics of morphine in children. Pharmacogenomics 15, 1297–1309 (2014).

Wachman, E. M. et al. Association of maternal and infant variants in PNOC and COMT genes with neonatal abstinence syndrome severity. Am. J. Addict. 26, 42–49 (2017).

Cole, F. S., Wegner, D. J. & Davis, J. M. The genomics of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Front. Pediatr. 5, 1–4 (2017).

Sadhasivam, S. et al. Morphine clearance in children: does race or genetics matter? J. Opioid Manag. 8, 217–226 (2012).

Emoto, C. et al. Characterization of contributing factors to variability in morphine clearance through (physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling implemented with OCT1 transporter. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 6, 110–119 (2017).

Lewis, T., Dinh, J. & Leeder, J. S. Genetic determinants of fetal opiate exposure and risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome: Knowledge deficit and prospect for future. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 98, 309–320 (2015).

Hauser, K. F. & Knapp, P. E. Opiate drugs with abuse liability hijack the endogenous opioid system to disrupt neuronal and glial maturation in the central nervous system. Front. Pediatr. 5, 1–23 (2018).

Grossman, M. R., Berkwitt, A. K. & Osborn, R. R. Racial association and pharmacotherapy in neonatal opioid withdeawal syndrome: thinking beyond genetics. J. Perinatol. 40, 689–690 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Gail Camp RN, Research Coordinator for obtaining consent form and gathering the data. We also thank the team of Social workers who help our mothers with OUD with their social needs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P. conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, initial analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the final version of manuscript. M.T.E. and R.D. carried out the initial and final analysis and reviewed the final manuscript. D.R. designed the data collection, collected data, carried out the initial analysis, and critically reviewed the final manuscript. K.P.G. and L.D. collected data and critically reviewed the final manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent

Patient consent was required and was obtained per our IRB guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pourcyrous, M., Elabiad, M.T., Rana, D. et al. Racial differences in opioid withdrawal syndrome among neonates with intrauterine opioid exposure. Pediatr Res 90, 459–463 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01279-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01279-4

This article is cited by

-

Comparing maternal substance use and perinatal outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Journal of Perinatology (2023)

-

Implicit Racial Bias in Evaluation of Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome

Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023)

-

Words matter

Pediatric Research (2022)