Abstract

Background

The BabyLux device is a prototype optical neuro-monitor of cerebral oxygenation and blood flow for neonatology integrating time-resolved reflectance spectroscopy and diffuse correlation spectroscopy.

Methods

Here we report the variability of six consecutive 30 s measurements performed in 27 healthy term infants at rest. Poor data quality excluded four infants.

Results

Mean cerebral oxygenation was 59.6 ± 8.0%, with intra-subject standard deviation of 3.4%, that is, coefficient of variation (CV) of 5.7%. The inter-subject CV was 13.5%. Mean blood flow index was 2.7 × 10−8 ± 1.56 × 10−8 (cm2/s), with intra-subject CV of 27% and inter-subject CV of 56%. The variability in blood flow index was not reduced by the use of individual measures of tissue scattering, nor accompanied by a parallel variability in cerebral oxygenation.

Conclusion

The intra-subject variability for cerebral oxygenation variability was improved compared to spatially resolved spectroscopy devices, while for the blood flow index it was comparable to that of other modalities for estimating cerebral blood flow in newborn infants. Most importantly, the simultaneous measurement of oxygenation and flow allows for interpretation of the high inter-subject variability of cerebral blood flow as being due to error of measurement rather than to physiological instability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

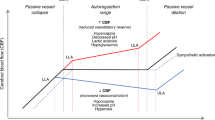

Despite improved treatment strategies, neurodevelopmental impairment is still a frequent consequence of preterm birth. Immature regulatory mechanisms for the control of cerebral blood flow (CBF) to ensure adequate oxygen delivery is thought to be a considerable part of the etiology.1

The BabyLux project aimed to develop a device to continuously monitor cerebral oxygenation and blood flow—and hence monitor oxygen metabolism—by near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), integrating time-resolved reflectance spectroscopy (TRS)2 with diffuse correlation spectroscopy (DCS)3 in a single device operating continuously under clinical conditions, providing robust measurements with a relatively high temporal resolution that would be suitable for use in neonates.4 In newborns, the distance from skin to brain is <5 mm, so optical methods could be particularly useful in this population.5

Most clinically approved NIRS devices use spatially resolved spectroscopy.6 To achieve absolute values these devices assume average optical properties for the investigated tissue. Such assumptions are possible sources of error,7 as optical properties reflect tissue composition, which changes during development of the central nervous system, for example, due to myelination. TRS measures the attenuation and temporal broadening as well as the time-of-flight of short light pulses propagating through tissue. By fitting measurements to a solution of the photon diffusion equation, TRS can separate absorption and scattering coefficients and resolve photon path lengths, allowing for direct, absolute determination of hemoglobin species concentrations.2

DCS relies on the interaction between long coherence laser light and moving scatters, which in tissue are red blood cells. The more moving scattering elements and the faster they move, the faster the loss of correlation of the reflected light is with its own source. Thus, an autocorrelation function can be used to quantify the microvascular blood flow in the illuminated tissue, and a blood flow index (BFI) can be calculated.3 It must be noted that optical properties, here measured by TRS, are needed as input parameters in order to retrieve absolute values of BFI. The combination of DCS and TRS allows for the assessment of an index of cerebral oxygen metabolism as tissue blood flow and oxygenation are measured simultaneously and independently.

The precision of quantitative measurements is a key parameter when evaluating the performance of medical devices, as clinical application usually targets normal ranges. The poorer the precision, the larger the confidence interval around a measurement becomes, and while this may be acceptable for research use, where the mean value for a number of subjects is relevant, poor precision always subtracts from the value for clinical decision making on the individual level. Clinically approved spatially resolved NIRS devices have usually been reported to have an intra-subject CV (standard deviation divided by the mean) of 6–7% on the newborn head8,9 determined by repeated repositioning of the probe.

In this paper, we report on the precision of the measurements taken with the BabyLux device in the clinical setting of healthy, term newborns at rest during their second day of life. A predefined goal of the BabyLux project was to improve the precision compared to spatially resolved NIRS devices.

Materials and methods

Protocol

The protocol was approved by local research ethics committees and national device agencies in both Italy and Denmark, and written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardian prior to inclusion. The clinical investigation has been monitored by external consultants according to ISO 14155:2011 “Clinical investigation of medical devices for human subjects—Good clinical practice.” The protocol is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier NCT02815618. The repeatability of measurements was evaluated by reapplying the BabyLux probe on the fronto-parietal region with the infant at rest. We targeted roughly the same position of the probe for every measurement, but did not use any markings on the skin to optimize precise repositioning and it is reasonable to expect variation in the positions to be <5 mm. A total of six measurement runs of 30 s duration each were completed for each infant with a total lift-off of the probe in between—the measurement-to-measurement interval normally lasting <60 s. Within each measurement run the acquisition time was 1 s for both DCS and TRS, thus a total of 180 measurements were obtained from six slightly varying positions within the same region for each infant. During measurements the probe was kept in place by a self-adhesive elastic bandage, and ambient light reduced by dark cloth, if needed, in case the instrument reported an unacceptable level of background light.

Subjects

Measurements were performed during the second day of life. Twenty-seven term infants delivered by elective cesarean section with a median (range) gestational age of 38 + 3 (37 + 0–9 + 5) weeks and birth weight of 3248 (2420–4330) g were included. Fourteen infants were enrolled in Milan, Italy and 13 in Copenhagen, Denmark. All infants were delivered without complications and had full Apgar scores at 10 min of age. Exclusion criteria were need for resuscitation or supplementary oxygen during the first 10 min following umbilical cord clamping, and congenital malformations expected to influence cerebral hemodynamics or oxygenation.

Instrumentation

The BabyLux device integrates TRS and DCS modules similar to those previously described by Torricelli et al.2 and Durduran and Yodh,3 respectively. In brief, the TRS module employs three pulsed lasers at 685, 760, and 820 nm. The pulse duration is <100 ps, with a repetition rate of 20 MHz, at an average output power <1 mW. A pulse driver enables proper delays of the three wavelengths allowing simultaneous acquisition within a 50 ns interval. TRS laser output is split by a fiber optic fused splitter in a reference branch, attenuated and fed directly to the photomultiplier, and a signal branch is directed to the probe to be placed on the tissue. Photons are collected by a multimode graded index plastic optical fiber in the probe, fed to the photomultiplier, and the distribution of time-of-flight (DTOF) for each wavelength accumulated in histograms. The DCS module uses a continuous wave long coherence laser at 785 nm carried in a multimode fiber with an output power of 20 mW at the probe surface regulated by a variable attenuator. DCS light is on for 9 s and off for 1 s, in order to allow dissipation of heat. According to the standard UNE-EN60825-1:2007, the maximum permissible exposure at 785 nm and with such exposure time is above the 20 mW value here used. The diffusely reflected light is collected in another window in the probe and measured by two single avalanche photodiodes. A custom-made correlator unit developed by HemoPhotonics S.L. computes the autocorrelation of the measured light intensity. The fiber optic probe head is made in aluminum with sapphire windows and deflects the light 90° in order to have a compact design. TRS and DCS source-detector separation is 15 mm. Since the light emission of the probe is not “eye-safe,” a capacitive sensor designed to detect skin contact is integrated in the probe head in order to ensure safe operation of the device, as lasers can only be switched on if contact is detected. A detailed description of probe design is available in Rehberger et al.10 The prototype device was approved for research use according to the clinical investigation plan by the national Medical Device Agencies in both Italy and Denmark. Figure 1 shows the design of the BabyLux device and probe.

Data processing and quality assessment

The dedicated BabyLux software display real-time estimates of the measured tissue oxygenation (StO2) and BFI, and provide continuously feedback of the quality of the acquired data. However, data for the analysis for this report were post-processed for thorough evaluation. The post-processing procedures of TRS data include estimation of the optical properties, determination of chromophore concentrations, and a quality evaluation of the results. For estimation of optical parameters (absorption coefficient (μa) and reduced scattering coefficient (μs′)), the DTOF is fitted with a model for photon diffusion after convolution with the instrument response function. The semi-infinite homogeneous medium model for photon diffusion has been chosen in our case taking into account the optical and geometrical characteristics of neonates (i.e., limited thickness of scalp and skull and relatively large absorption), as it also enables depth sensitivity with less contribution from extracerebral layers using only one source-detector separation.11 The fitting procedure is described in detail in Cubeddu et al.12 Beer’s law is used to determine the concentration of oxy-hemoglobin (O2Hb) and deoxy-hemoglobin (HHb), from which total hemoglobin (HbT = O2Hb + HHb) and “tissue”-oxygenation, StO2 = (O2Hb)/HbT can be derived. Specific absorption values for hemoglobin are taken from the Prahl dataset.13 Lipid content in brain of neonates is limited and therefore disregarded, while water content is fixed at 90%.14 TRS data quality is sensitive to the number of photons in the DTOF. We consider values of >103 photons per DTOF as acceptable. χ2 test is used to evaluate quality of the fit. Large values (χ2 >10) indicate a poor match between experimental data and fitting model and are discarded. Very low values (χ2 < 0.1) are discarded as they may indicate a very low photon count. Further, the photon diffusion model assumes that photon loss due to scattering is much larger than absorption (μs′ » μa); hence, if the fit provides too low values for μs′ (i.e., <1 cm−1), the model may be violated, and values are excluded.

The normalized intensity field autocorrelation curve acquired in DCS measurements are fitted to the solution of the diffusion equation for the autocorrelation function for the semi-infinite homogeneous geometry. As the source-detector separation is known and optical properties at 760 nm have been estimated by TRS, they can be inserted in the model, enabling determination of BFI. DCS curves acquired with an intensity rate below 10 kHz are excluded, due to poor signal-to-noise ratio, or when the laser is switching on or off for 1 s every 9 s (a safety precaution enabling measurements that last for hours). The optical properties influence BFI, which is particularly sensitive to the estimate of μs′. In theory, μs′ is not expected to change considerably even during a change in blood flow. To balance the need for individual optical properties and measurement errors, BFI has been calculated with both the individual infant’s μs′ averages and as well as the grand average of all individuals’ μs′. In both cases data for μs′ at 760 nm were used. Since μa varied less and is less critical for the calculation of BFI, only the individual averages were used. DCS results with residuals >2 SD from the individual mean have been rejected.

Statistical analysis

The BFI was logarithmically transformed (log(BFI)) to obtain a normal distribution before further analysis. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with μs′, μa, StO2, HbT, and log(BFI) as dependent variables and subject as random factor was used for the determination of within-subjects and between-subjects variance over the six replacements. Variation for variables following a normal distribution is reported as coefficient of variance (CV). BFI is reported as geometric statistics for log-normal distributions. The correlation between StO2 and log(BFI) were tested using Pearson’s regression.

Results

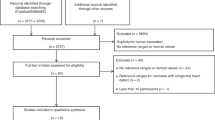

Of 27 enrolled infants, 23 were included in statistical analysis after applying quality criteria for the measurements as described above. In 2 of the 23 infants, 1 of the 6 StO2 measurements did not meet the quality criteria, and in 7 of the 23 infants, 1 to 3 of the 6 BFI measurements did not, 9 in total. Figures 2 and 3 show mean values of StO2 and BFI for each of the up to six 30 s measurements for all infants analyzed listed by subject. Figure 4 illustrates mean values of μs′ for each TRS wavelength over all measurements listed by subject.

The average StO2 value was 59.6 ± 8.0% SD (range 37.0–72.5%) across infants. The intra-subject standard deviation was 3.4%, that is, the CV (CVintra) of StO2 was 5.7% and inter-subject CV (CVinter) 13.5%. The BFI geometrical average was 2.71 × 10−8 cm2/s (range 0.63 × 10−8–6.93 × 10−8 cm2/s) when using the grand average μs′ for all infants with CVintra of 27% and CVinter of 56%. For BFI estimated using average μs’ for each individual infant geometric average BFI was 2.89 ××10−8 cm2/s (range 0.89× 10−8–2.57 ×10−7 cm2/s) with CVintra of 28% and CVinter of 89%. Table 1 summarizes the main results for optical properties by wavelength and cerebral hemodynamics.

Tests for inhomogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) were significant for both StO2 (p < 0.001) and BFI (p < 0.0001) (Table 2), demonstrating that the replacement variability was particularly large in some infants as illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3.

The relationship between StO2 and log(BFI) did not show any correlation during the replacements (R2 = 0.003, p = 0.524).

Discussion

The absolute values of StO2 were comparable to previous reports using frequency domain NIRS,15,16 although several infants displayed low values (Fig. 2). It is noticeable that these values are not calibrated, but are modelled directly from in vitro extinction coefficients of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin. Spatially resolved NIRS devices have in general reported a higher StO2. Studies of normal reference values for cerebral StO2 has focused on preterm or critically ill infants, but two studies report values around the second day of life in healthy term infants of 78 ± 6–8% with the spatially resolved INVOS system.17,18 This is substantially higher than the 60 ± 8% we observe. However, NIRS devices are known to vary greatly in absolute values and the INVOS with the neonatal/pediatric sensor measures notoriously higher values than most other systems,19 perhaps caused by the in vivo calibration that is often used.

Recently, using another TRS system (with 3 cm source-detector distance and 600 ps full-width at half-maximum of the instrument response function), TRS measurements on the head of 33 healthy term infants around the third day of life were performed yielding a median StO2 of 72% and having approximately twice the absorption coefficient and total hemoglobin concentration than in our study.20 In that work, the combination of a TRS system with a significantly wider instrument response function with a larger source detector distance is likely to have resulted in a greater lateral spreading of photons,21 resulting in sampling from a larger volume of tissue (superficial and cerebral), as well as a greater effect of head curvature, that is, escape of photon head from boundaries,22 is likely to have contributed to the difference. Finally, the expected accuracy of the estimates of tissue optical properties23,24 is lower than for the BabyLux system.

Absolute values of BFI were close to expected values,25 whereas the variability of the BFI appeared high, and was not reduced by use of individually measured μs′ as anticipated. Although BFI is an absolute quantification, the rather unconventional unit of cm2/s is not understandable for clinicians who are used to the unit ml/100 g/min. Several studies have validated DCS against other modalities demonstrating a strong correlation, whereas only a few report calibrations.3 Using such a calibration, obtained in piglets comparing DCS with TRS combined with a flow tracer,26 our average BFI of 2.71 × 10−8 cm2/s equals 23.6 ml/100 g/min, which is in the expected range of CBF for healthy term infants.27,28

Furthermore, neither the intra- nor the inter-subject variabilities were correlated between StO2 and BFI. This could be expected, given that spontaneous fluctuations in CBF due to vasomotion would cause parallel changes in StO2, since it may be assumed that CMRO2 is relatively constant in healthy, term newborn infants at rest. These last findings suggest that the variabilities are for a significant part caused by measurement errors, rather than spontaneous changes in cerebral physiology during the periods the replacements were done.

It should be noted that no efforts were made to remove motion artifacts, besides the objective quality criteria stated above. Especially the BFI is sensitive to motion and to pressure applied by the bandage. This is also reflected in the large and physiologically implausible range of CBF measurements, which spans a factor of more than 10 when calculated with the grand average μs′, and this variability was even larger when calculated with individual μs′.

The assessment of variability between repositions in our protocol relies on the brain to be in a stable resting state throughout the measurement. This clinical test design aimed at evaluating “real-life” performance as expected under normal clinical conditions. The handling of the infant for the purpose of resiting the sensor with removal and re-application of the self-adhesive bandage may have resulted in some infants changing behavioral state. Further, normal physiological fluctuations relayed from systemic functions (e.g., arterial oxygen saturation, heart rate, respiration, and baro-reflex vasomotion) are reflected in cerebral hemodynamics and oxygenation despite autoregulation, or may even be an inherent trait of cerebral circulation improving its overall stability.29 In our protocol each measurement lasts 30 s (0.033 Hz). Since the sample rate will work as simple filter, intra-subject variability will not reflect variations caused by heart rate (2–3 Hz) and respiration (approx. 1 Hz), but could vary with vasomotion (0.1–0.01 Hz) or arterial saturation (more random). However, the amplitudes of such physiologic oscillations in the cerebral hemodynamics are likely small compared to the variability observed in our study.30

The variation in CBF in the normal human newborn is not well known because of methodological limitations. Using the “gold-standard” method, positron emission tomography (PET) in the normal, resting adult, the CV is about 15%,31 while after normalizing for differences in global CBF, the CV in CBF is 5–10% among subjects and about 10% among cortical areas.32,33 In a recent study of healthy, resting newborn infants using PET, the CV of CBF in the frontal cortex among the four subjects was 23%27 in good agreement with the adult situation. In preterm infants a similar CVinter of 27% for CBF in the frontal region have been demonstrated using the 133Xenon clearance method.34 We therefore find it reasonable to assume that the true inter-subject variability is around 25% in normal, healthy term infants when transition after birth has taken place. This means that the BFI inter-subject variability of 56% seen in the present study is increased by measurement error. A recent similar study using frequency domain NIRS and DCS had a comparable BFI inter-subject CV of 38%,16 if ignoring the skewed nature of the data, which in our case would give a CVinter of 43%. However, it should be noted that measurement variability is not easily compared across modalities as temporal resolution varies greatly, from seconds with optical methods to minutes with PET, due to differences in protocol for data acquisition and processing. For comparison, the precision of the BFI obtained by the BabyLux instrument in a phantom and in a piglet model was in the order of 5%35 and the signal variability within the 30-s measurement periods in the dataset acquired in the present study was 10%, only, as previously published.36

The BabyLux hybrid device used in the present study allowed simultaneous estimation of μs′ by TRS in each infant. When the DCS BFI was calculated using this individual μs′, the inter-subject CV was increased, not decreased. We interpret this as an indication that this “individualization” in effect added error to the estimation of CBF. Although the measurement of μs′ was ineffective in improving the precision of BFI, the unexpectedly large inter-subject variability of μs′, suggests that one important reason for the very poor precision of BFI in human infants is optical heterogeneity, probably due to pools of cerebrospinal fluid due to relatively open sulci between the growing gyri. To support this, in four infants, the estimated μs′ for each of the wavelengths 690, 760, and 820 nm, did not display the expected “linear” decrease (subject B, E, T, and V, Fig. 4). This was likely to be due to error of measurement, since the six replications were particularly variable in three of the four infants—possibly due to the marginally different average pathways of photons of different wavelength, and overall the deviation from the expected pattern in these four infants was hardly statistically significant.

Data on inter-subject variation of cerebro-venous oxygenation in normal newborn infants is also scarce. There are no data using blood sampling and co-oximetry due to ethical reasons. The first data was provided for seven infants using continuous wave NIRS and jugular venous occlusion. The inter-subject CV was 15.4%.37 Recently, magnetic resonance imaging was used to estimate oxygenation in the superior sagittal sinus in 10 infants, yielding a CVinter of 16%. Although brain StO2, estimated by TRS as in the present study, is a different quantity, the CVinter was similar, 13.5%, but apparently higher when estimated by frequency domain NIRS at 26%.16

The BabyLux device’s improvement in intra-subject CV for StO2 seems modest, but should be assessed in the context of the lower mean value. Simply looking at the intra-subject standard deviation of 3.4%, not affected by the mean values, the improvement is considerable, and corresponds to a reduction in the 95% confidence interval for a measurement to ±9%-points, as opposed to ±13%-points for spatial resolved NIRS.8,9 Recently, a new spatially resolved spectroscopy NIRS device has produced lower intra-subject CV for StO2, possibly related to interrogating a larger brain volume and/or an auto-calibration function.38 Reducing the confidence interval has a great impact on the clinical usefulness of a measurement as therapeutic ranges are often narrow and patient management often rely on intervention thresholds, making the reliability of the absolute value decisive.

Conclusion

We obtained simultaneous measurements of cerebral StO2 and BFI in healthy, term newborn infants at rest with acceptable short time reposition coefficient of variability of approximately 5% (≈SD 3.4%) and 25%, respectively. The reposition variability of StO2 meets our predefined goal of improvement compared to spatial resolved NIRS devices, while the reposition variability of BFI is in the same range as other modalities for CBF measurement in infants, but with the advantage of being method that can be used bedside and in real time. For the inter-subject variability, the BabyLux device compared well with other modalities for cerebral StO2—13.5% compared to typical values of 15%, but not for CBF with 56% compared to typical values of 25%. Most importantly, the simultaneous measure of oxygenation and flow, and the lack of correlation between these measures, allows to interpret the the high inter-subject variability of CBF as being due to error of measurement rather than physiological instability. Most likely true inter-individual variability of cerebral blood flow in healthy, stable, term infants is not greater than it is in other groups of healthy individuals.

References

Volpe, J. J. Brain injury in premature infants: a complex amalgam of destructive and developmental disturbances. Lancet Neurol. 8, 110–124 (2009).

Torricelli, A. et al. Time domain functional NIRS imaging for human brain mapping. NeuroImage 85 Part 1, 28–50 (2014).

Durduran, T. & Yodh, A. G. Diffuse correlation spectroscopy for non-invasive, micro-vascular cerebral blood flow measurement. NeuroImage 85 Part 1, 51–63 (2014).

Weigel, U. M. et al. The BabyLux project—an optical neuro-monitor of cerebral oxygen metabolism and blood flow for neonatology. Biomed. Opt. OSA Technical Digest (online), paper JM3A.30 (2016).

Greisen, G., Andresen, B., Plomgaard, A. M. & Hyttel-Sørensen, S. Cerebral oximetry in preterm infants: an agenda for research with a clear clinical goal. Neurophotonics 3, 031407 (2016).

Scholkmann, F. et al. A review on continuous wave functional near-infrared spectroscopy and imaging instrumentation and methodology. NeuroImage 85 Part 1, 6–27 (2014).

Metz, A. J., Biallas, M., Jenny, C., Muehlemann, T. & Wolf, M. The effect of basic assumptions on the tissue oxygen saturation value of near infrared spectroscopy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 765, 169–175 (2013).

Hyttel-Sorensen, S., Hessel, T. W., la Cour, A. & Greisen, G. A comparison between two NIRS oximeters (INVOS, OxyPrem) using measurement on the arm of adults and head of infants after caesarean section. Biomed. Opt. Express 5, 3671–3683 (2014).

Hessel, T. W., Hyttel-Sorensen, S. & Greisen, G. Cerebral oxygenation after birth—a comparison of INVOS((R)) and FORE-SIGHT near-infrared spectroscopy oximeters. Acta Paediat. (Oslo, Norway: 1992) 103, 488–493 (2014).

Rehberger, M. et al. Fiber-based hybrid probe for non-invasive cerebral monitoring in neonatology. In Diffuse Optical Imaging V (H. Dehghani & P. Taroni, eds.) Vol. 9538 of SPIE Proceedings (Optical Society of America, 2015), paper 95381J.

Giusto, A. et al. Monitoring absorption changes in a layered diffusive medium by white-light time-resolved reflectance spectroscopy. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 59, 1925–1932 (2010).

Cubeddu, R., Pifferi, A., Taroni, P., Torricelli, A. & Valentini, G. Experimental test of theoretical models for time-resolved reflectance. Med. Phys. 23, 1625–1633 (1996).

Oregon Medical Laser Center. Optical Absorbption of Hemoglobin (Oregon Medical Laser Center, 1999). http://omlc.ogi.edu/spectra/hemoglobin.

Dobbing, J. & Sands, J. Growth and development of human brain. Arch. Dis. Child 48, 757 (1973).

Demel, A. et al. Healthy term and moderately preterm infants have similar cerebral oxygen saturation and cerebral blood flow volumes during early postnatal transition. Acta Paediatr. 104, e330–336 (2015).

Farzam, P. et al. Shedding light on the neonatal brain: probing cerebral hemodynamics by diffuse optical spectroscopic methods. Sci. Rep. 7, 15786 (2017).

Bailey, S. M., Hendricks-Munoz, K. D. & Mally, P. Cerebral, renal, and splanchnic tissue oxygen saturation values in healthy term newborns. Am. J. Perinatol. 31, 339–344 (2014).

Bernal, N. P., Hoffman, G. M., Ghanayem, N. S. & Arca, M. J. Cerebral and somatic near-infrared spectroscopy in normal newborns. J. Pediatr. Surg. 45, 1306–1310 (2010).

Kleiser, S., Nasseri, N., Andresen, B., Greisen, G. & Wolf, M. Comparison of tissue oximeters on a liquid phantom with adjustable optical properties. Biomed. Opt. Express 7, 2973–2992 (2016).

Spinelli, L. et al. In vivo measure of neonate brain optical properties and hemodynamic parameters by time-domain near-infrared spectroscopy. Neurophotonics 4, 041414 (2017).

Feng, S., Zeng, F.-A. & Chance, B. Photon migration in the presence of a single defect: a perturbation analysis. Appl. Opt. 34, 3826–3837 (1995).

Liemert, A. & Kienle, A. Light diffusion in a turbid cylinder. I. Homogeneous case. Opt. Express 18, 9456–9473 (2010).

Wabnitz, H. et al. Performance assessment of time domain optical brain imagers, part 1: Basic physical performance protocol. J. Biomed. Opt. 19, 086011 (2014).

Zucchelli, L., Contini, D., Re, R., Torricilli, A. & Spinelli, L. Method for the discrimination of superficial and deep absorption variation by time domain fNIRS. Biomed. Opt. Express 4, 2893–2910 (2013).

Lin, P. Y. et al. Regional and hemispheric asymmetries of cerebral hemodynamic and oxygen metabolism in newborns. Cereb. Cortex. (United States) 23, 339–348 (2013).

Giovannella, M. et al. Validation and Potential Calibration Of Diffuse Correlation Spectroscopy versus (15)O-Water Positron Emission Tomography on Neonatal Piglets, fNIRS2018 (Society for Functional Near-infrared Spectroscopy, Tokyo, 2018).

Andersen, J. et al. Hybrid PET/MRI imaging in healthy unsedated newborn infants with quantitative rCBF measurements using (15)O-water PET. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 39, 782–793 (2019).

Greisen, G. Cerebral blood flow in preterm infants during the first week of life. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 75, 43–51 (1986).

Garrett, D. D. et al. Moment-to-moment brain signal variability: a next frontier in human brain mapping? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 610–624 (2013).

Kirilina, E. et al. Identifying and quantifying main components of physiological noise in functional near infrared spectroscopy on the prefrontal cortex. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 864 (2013).

Henriksen, O. M. et al. Estimation of intersubject variability of cerebral blood flow measurements using MRI and positron emission tomography. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 35, 1290–1299 (2012).

Vaishnavi, S. N. et al. Regional aerobic glycolysis in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17757–17762 (2010).

Aanerud, J., Borghammer, P., Rodell, A., Jonsdottir, K. Y. & Gjedde, A. Sex differences of human cortical blood flow and energy metabolism. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 37, 2433–2440 (2017).

Baenziger, O. et al. Regional differences of cerebral blood flow in the preterm infant. Eur. J. Pediatr. 154, 919–924 (1995).

Giovannella M. et al. Accuracy and precision of tissue optical properties and hemodynamic parameters estimated by the BabyLux device: a hybrid time-resolved near-infrared and diffuse correlation spectroscopy neuro-monitor. Biomed. Opt. Express 10, 2556–2579 (2019).

Giovannella, M. et al. The BabyLux Device: Baseline Hemodynamic and Optical Properties of the Newborn Brain and the Reproducibility of Measurements. In Biophotonics Congress: Biomedical Optics Congress 2018 (Microscopy/Translational/Brain/OTS), OSA Technical Digest (Optical Society of America, 2018), paper OW4C.2.

Buchvald, F. F., Kesje, K. & Greisen, G. Measurement of cerebral oxyhaemoglobin saturation and jugular blood flow in term healthy newborn infants by near-infrared spectroscopy and jugular venous occlusion. Biol. Neonate 75, 97–103 (1999).

Kleiser, S. et al. In vivo precision assessment of a near-infrared spectroscopy-based tissue oximeter (OxyPremv1.3) in neonates considering systemic hemodynamic fluctuations. J. Biomed. Opt. 23, 067003 (2018).

Kirkwood, T. B. L. Geometric means and measures of dispersion. Biometrics 35, 908–909 (1979).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all collaborators in the BabyLux consortium and the parents of the infants included in the clinical investigation. This research was funded by the European Commission Competitiveness for Innovation Program (grant agreement no. 620996) as part of the project titled: An optical neuro-monitor of cerebral oxygen metabolism and blood flow for neonatology (BabyLux).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to conception, design, data acquisition. or analysis or interpretation: All. Drafting and revising article: B.A., A.D.C., M.F., M.G., D.C., L.S., A.T., G.G. Final approval: All.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The IP generated during the BabyLux project is owned by the technological partners. U.M.W. is the CEO, has equity ownership in HemoPhotonics S.L., and is an employee in the company. His role in the project has been defined by the project objectives, tasks, and work-packages, and was reviewed by the European Commission. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andresen, B., De Carli, A., Fumagalli, M. et al. Cerebral oxygenation and blood flow in normal term infants at rest measured by a hybrid near-infrared device (BabyLux). Pediatr Res 86, 515–521 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0474-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0474-9

This article is cited by

-

Wearable fiber-free optical sensor for continuous monitoring of neonatal cerebral blood flow and oxygenation

Pediatric Research (2024)

-

Assessing cerebral blood flow, oxygenation and cytochrome c oxidase stability in preterm infants during the first 3 days after birth

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

The future of noninvasive neonatal brain assessment: the measure of cerebral blood flow by diffuse correlation spectroscopy in combination with near-infrared spectroscopy oximetry

Journal of Perinatology (2021)

-

Foetal growth, birth transition, enteral nutrition and brain light scattering

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Dynamics of cortical oxygenation during immediate adaptation to extrauterine life

Scientific Reports (2021)