Abstract

Introduction

Maternal overweight/obesity and comorbid hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes associate with neurodevelopmental delay in the offspring in childhood. We hypothesize that these maternal conditions associate also with the offspring regulatory behavior problems and impact on neurodevelopment via the offspring regulatory behavior.

Methods

A number of 3117 women of the PREDO Study filled in a questionnaire on regulatory behavior problems at the child’s mean age of 16.9 days and 2116 of them a questionnaire on developmental milestones at the child’s mean age of 42.2 months. Data on maternal BMI and comorbid disorders come from the Finnish Medical Birth Register.

Results

Offspring of overweight/obese mothers in comparison to normal weight mothers had higher levels of regulatory behavior problems and 22% (95% confidence interval 5–42%) higher odds of having problems on multiple domains of behavioral regulation at the mean age of 16.9 days. Offspring regulatory behavior problems partially mediated the association between maternal overweight/obesity and developmental milestones comprising communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving, and personal/social domains of development. Comorbid disorders did not associate with offspring regulatory behavior problems.

Conclusion

Regulatory behavior problems of the offspring have prenatal origins and partially mediate the effects of maternal overweight/obesity on offspring neurodevelopment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 20% of infants during the first year of life experience regulatory behavior problems that manifest in excessive crying, fussiness, and difficulties related to sleeping or feeding.1 These regulatory behavior problems in infancy predict childhood behavioral and neurodevelopmental adversities, namely behavior problems, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),1,2,3,4,5,6 autism spectrum disorder (ASD),7 lower IQ,8 and disadvantages in motor function9 in early and middle childhood (up to the age of 13 years). Since regulatory problems in infancy, especially those affecting multiple areas of infant’s behavioral regulation, indicate the risk of future behavioral and neurodevelopmental adversity,1 it is essential to identify factors that may underpin these early-emerging problems in self-regulation.

Preterm birth (defined as a birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation) and low birth weight (defined as a birth weight of <2500 g) are among the known risk factors for regulatory behavior problems in infancy.10 These findings are in line with the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis, which suggests that exposure to environmental adversity in the prenatal life may alter the structure and functioning of cells, tissues and organs, and body’s physiological feedback systems, and thereby increase the risk for behavioral and neurodevelopmental problems later in life. Preterm birth and low birth weight are, however, crude proxies of exposure to environmental adversity in the prenatal period, and hence do not inform about the potential underlying mechanisms. Maternal overweight/obesity and comorbid hypertensive (gestational and chronic hypertension and preeclampsia) and diabetic (gestational diabetes mellitus, GDM) disorders are among the key underlying causes of preterm birth and low birth weight.11 It remains unclear if these maternal conditions are related to infant regulatory behavior problems, even though there exists some evidence which suggests that they are associated with the child’s risk of ADHD,12,13 ASD,14 developmental delay,13,15 and impaired cognition.16 We are aware of only one study which has shown that maternal pre-pregnancy obesity was not associated with 2–32-day-old term-born (defined as births between 37 and 42 completed weeks of gestation) infants’ neurobehavior measured with NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale, which includes a summary score of self-regulation (self and other soothing capabilities).17 In this study pre-pregnancy obesity was, however, self-reported and it did not account for the associations between the comorbid hypertensive disorders or GDM and infant behavioral self-regulation. Furthermore, it also remains unclear whether infant regulatory behavior problems mediate the associations between maternal overweight/obesity and the comorbid disorders and child neurobehavioral development.

To fill in these gaps in the research literature, the current study sought to determine associations between maternal early pregnancy overweight/obesity and co-morbidities, including gestational and chronic hypertension, preeclampsia and GDM, and infant regulatory behavior problems. Our study also explored if infant regulatory behavior problems mediated the associations between these maternal conditions and the child’s developmental milestones in early childhood.

Methods

The participants came from the Prediction and Prevention of Pre-eclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction (PREDO) study, a prospective multicenter study of Finnish women who were pregnant between 2005 and 2009. The study enrolled 4785 pregnant women, of whom 4777 gave birth to a singleton live child between 2006 and 2010.18 To enrich the number of women with preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) in the PREDO sample, 969 of the recruited women had one or more risk factors for preeclampsia and IUGR, including early pregnancy obesity and chronic hypertension.18 PREDO study design is described in detail elsewhere.18

Follow-up assessment of infant’s regulatory behaviors was conducted up to 3 months after the delivery. In total, 3180 women (66.6%) provided ratings of their infant’s regulatory behaviors. From this sample, we excluded 44 women who filled in the survey more than 5 standard deviations (SD) from the mean time and were considered as outliers and 19 women with type 1 diabetes, since the number was too small to study its effect. The analytic sample comprised 3117 mother–child dyads with data on maternal early pregnancy overweight/obesity, hypertensive disorders and GDM, and infant’s regulatory behaviors rated by the mother at the infant’s mean age of 16.9 days (SD 7.4 days; range 1–90 days).

Follow-up assessment of child’s developmental milestones was conducted in 2011–2012. In total, 2667 (55.8% of those giving live birth; 85.5% of those with ratings on infant regulatory behaviors) women rated their child’s developmental milestones at the child’s mean age of 42.1 months (range 23.2–68.8 months). In total, 163 mothers filled in the age-specific developmental milestones questionnaire too early or too late for age and were excluded. Maternal early pregnancy overweight/obesity, hypertensive disorders and GDM, infant regulatory behaviors, and child developmental milestones were available for 2116 mother–child dyads for the mediation analyses.

Women in the analytic sample for analyses of infant regulatory behaviors, namely those who had data on overweight/obesity, comorbid disorders, and infant regulatory behaviors, were older and were more often primiparous as compared to women who did not have these data and hence were not included in this analytic sample (p-values < 0.001). Women in the analytic sample for the mediation analyses, namely those who had data on overweight/obesity and comorbid disorders, infant regulatory behaviors, and early childhood developmental milestones, had a higher level of education (p = 0.0003), were more often primiparous (p = 0.006), had less often hypertensive pregnancy disorders (p = 0.002), and less often gave birth to boys (p = 0.04), as compared to women who did not have these data, and hence were not included in the mediation analyses. There were no differences in other maternal or child perinatal characteristics between these groups (p-values > 0.12).

Maternal overweight/obesity and hypertensive and diabetic disorders

Data were extracted from the Finnish Medical Birth Register (MBR).19 For the subsample recruited based on their increased risk of preeclampsia and IUGR, each individual diagnosis was further verified by a clinical jury consisting of two physicians and a nurse.

Early pregnancy BMI was calculated from height and weight verified by a measurement conducted by a nurse at the first visit to the antenatal clinic (M = 8 + 4 weeks + days, SD = 1 + 3 weeks + days of gestation), and categorized to normal weight (<25 kg/m2 or less) and overweight/obese (≥25 kg/m2) groups according to the World Health Organization criteria;20 104 women (3.3%) had BMI below 18.5 kg/m2 indicating underweight; the underweight and normal weight groups were pooled for the analyses (infant regulatory behavior problems were not different between underweight and normal weight groups: mean difference = −0.18 SD, 95% CI −0.38, 0.01; from here on referred to as “normal weight”).

Gestational hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg on ≥2 occasions at least 4 h apart in a woman who was normotensive before 20 weeks of gestation; preeclampsia as blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg on ≥2 occasions at least 4 h apart in a woman with new-onset proteinuria ≥300 mg/24 h after 20 weeks of gestation. We also identified women with chronic hypertension defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg present before pregnancy or before the 20th week of gestation.

Gestational diabetes was defined as fasting, 1 or 2 h plasma glucose during a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test ≥5.1, 10.0, and/or 8.5 mmol/L that emerged or was first identified during pregnancy. None of the women in our sample had type 2 diabetes.

Infant regulatory behavior problems

Infant’s regulatory behavior problems were rated by the Neonatal Perception Inventory (NPI),21,22 which evaluates behaviors related to crying, feeding, spitting, elimination (bowel movements), sleeping, and predictability. In order to decrease potential bias pertaining to subjective perceptions of infant behaviors, we first asked the mother to rate concerns related to regulatory behaviors she would expect an “average” infant to display. Then we asked her to rate concerns regarding her own infant’s regulatory behaviors. The ratings were made using a five-point scale ranging from no problems (1) to a great number of problems (5). A difference score between her own and the average infant’s regulatory behaviors (own infant − average infant) reflects more regulatory behavior problems in her own infant.23 In addition to this difference score, we calculated an ordinal “accumulation” variable which indicated the number of areas in which the infant had regulatory problems (own infant had more problems than an average infant on any of the six subscales; score 0–6).

Developmental milestones

Developmental milestones were rated by the Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ) Third edition24 (translated into Finnish and back-translated and approved by the publisher). ASQ is a reliable and valid tool with high sensitivity and specificity to screen children requiring further developmental assessment, monitoring, or special education.24,25 It comprises 30 age-appropriate items (in our sample for children aged 22.2–26.2, n = 75, 24.5–29.5, n = 67, 27.5–32.5, n = 93, 30.5–35.5, n = 199, 33.0–41.5, n = 377, 37.0–47.0, n = 463, 42.0–53.0, n = 618, 55.0–59.0, n = 205, and 54.0–69.0 months, n = 29) measuring communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving, and personal/social skills.

Each domain comprises six questions with the responses “yes” (scored 10), indicating the child can master the skill, “sometimes” (scored 5) if the skill is emerging or occasional, and “not yet” (scored 0) if the child is not able to perform the skill; scores range from 0 to 60 with the highest value indicating mastering of the skill. In this study, we used the total developmental milestones score calculated as a sum of the subscale scores.26

Covariates

The following factors were included as covariates in our analysis: maternal age at childbirth (years), parity (primiparous/multiparous), delivery mode (vaginal/cesarean), maternal smoking during pregnancy (did not smoke/quit during the first trimester/smoked throughout pregnancy), child’s gestational age at delivery (weeks), birth weight (grams), and sex (boy/girl) with data extracted from patient case reports and/or the MBR, and maternal alcohol use during pregnancy (yes/no) and education level (basic/secondary vs. tertiary) as self-reported in early pregnancy; and child’s age at follow-ups reported in conjunction with filling in the child assessments.

Statistical analyses

We applied linear regression analyses to examine the associations between maternal early pregnancy overweight/obesity and comorbid disorders and infant regulatory behavior problems total difference score. When we tested associations with the infant regulatory behavior problems on multiple behavioral domains (0 [n = 1741], 1 [n = 813], 2 [n = 359], 3 [n = 151], 4 [n = 72], 5 [n = 27], and 6 [n = 6]), we used the continuation-ratio ordinal logistic regression.

To eliminate any potential confounding or effect modification by these comorbid conditions, we tested the effects of overweight/obesity by excluding women with other disorders from the analyses, which allowed us to assess the unique effect of overweight/obesity on infant regulatory behaviors. We also examined if overweight/obesity and hypertensive disorders and GDM had additive effects by including an interaction term “overweight/obesity vs normal weight × hypertensive disorders or GDM vs no disorders” into the regression models.

We also explored whether any potential associations between maternal overweight/obesity and comorbid disorders and child developmental milestones were mediated by infant regulatory behavior problems by using the PROCESS macro for SPSS with 5000 bootstrapped samples.27 Before applying the mediation analysis, we verified that the associations between maternal overweight/obesity and developmental milestones and between regulatory behavior problems and developmental milestones in our sample were statistically significant (p-values < 0.05).

Linear and logistic regression analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Mediation analysis was performed using SPSS-IBM (Software, v.24.0 SPSS).

Results

Characteristics of the study sample according to maternal early pregnancy overweight/obesity and normal weight are presented in Table 1. Overweight/obese mothers in comparison to normal weight mothers were older at delivery, less often had a tertiary education, more often quit smoking during the first trimester, and more often delivered by a cesarean section. Overweight/obese mothers also had a higher prevalence of hypertensive disorders and GDM (Table 1).

Associations between maternal overweight/obesity and comorbid disorders and infant regulatory behavior problems

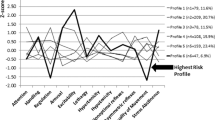

Table 2 shows that maternal overweight/obesity in comparison to normal weight was associated with higher infant regulatory behavior problems total difference score. Table 2 also shows that infants of overweight/obese mothers were also more likely to have multiple regulatory behavior problems. These associations held when we excluded women who had hypertensive disorders and GDM from the analyses (Fig. 1). Figure 1 shows that the predicted probability of a mother to be overweight/obese increased as the level (panel a) and the likelihood of the infant to have multiple regulatory behavior problems (panel b) increased. There were no significant associations between maternal hypertensive disorders and GDM and infant regulatory behavior problems (Table 2). Maternal overweight/obesity and hypertensive disorders and GDM did not show additive effects (p = 0.26 and 0.30 for overweight/obesity vs. normal weight × hypertensive disorders/GDM vs. no disorder interactions in the analyses of regulatory behavior problems total difference score and multiple regulatory behavior problems, respectively).

Mediation analysis

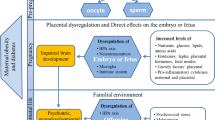

As shown in Fig. 2, higher level of infant regulatory behavior problems total difference score (panel a) and problems on multiple domains of behavioral regulation (panel b) were associated with lower total developmental milestones score in childhood (−0.06, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] −0.10, −0.01, and −0.05, 95% CI −0.01 and −0.09, respectively). Furthermore, children of overweight/obese mothers in comparison to normal weight women had lower total developmental milestones scores in childhood (−0.10, 95% CI −0.19 and −0.01) (Fig. 2). Figure 2 also shows that infant regulatory behavior problems partially mediated the effect of maternal overweight/obesity on lower childhood developmental milestones total difference score (−0.006, 95% CI −0.02 and −0.001) (panel a) and on problems on multiple domains of behavioral regulation (−0.01, 95% CI −0.02 and −0.002) (panel b).

Mediation analyses results showing that maternal early pregnancy overweight/obesity partly acts via infant regulatory behavior problems total difference score (a) and via infant problems on multiple domains of behavioral regulation (b) to impact on total developmental milestones score in early childhood. Numbers represent adjusted standardized coefficients and 95% confidence intervals

Discussion

Our study showed that infants of the mothers with early pregnancy overweight/obesity, in comparison to infants of the mothers with early pregnancy normal weight had higher levels of regulatory behavior problems at the age of 16.9 days. Our study also showed that maternal overweight/obesity was associated with 22% (95% CI 5–42%) higher odds of having problems on multiple domains of behavioral regulation. These associations were not accounted for by the comorbid hypertensive disorders or GDM, which was in contrast to what we expected, as there was no significant association with infant regulatory behavior problems. Maternal hypertensive disorders or GDM did not either add to the effects of maternal overweight/obesity. None of these effects was accounted for by a number of other important covariates, including maternal and child perinatal characteristics. Hence, our findings show that regulatory behavior problems in infancy have prenatal origins that can be attributed at least partially to maternal overweight/obesity.

These findings are in line with the previous studies that have shown that preterm birth and low birth weight increase the risk of having regulatory problems in infancy.10,28,29,30 Our findings, however, are not in accordance with the only previous study that we are aware of that found that maternal obesity during pregnancy was not associated with 2–92-day-old term-born infant’s self-regulation.17 This study, however, used self-reports of maternal weight and height and used a summary measure of infant neurobehavior which included infant’s self- and other soothing capabilities and the sample was restricted to those born at term. Our study findings are therefore not directly comparable with the findings of this previous study. Hence, our findings lend credence to the Developmental Origins or Health and Disease (DOHaD) concept,31 and for the first time demonstrate that maternal overweight/obesity that increase the risk of preterm birth and IUGR may be a condition that underpins these previously reported associations.

Another novel finding of our study is that infant regulatory behavior problems partially mediated the effects of maternal overweight/obesity on the child’s poorer achievement on a measure of developmental milestones at the child’s mean age of 3.5 years. This finding is noteworthy, as a number of studies have shown the predictive significance of early life regulatory behavior problems on childhood neurobehavioral adversity, including externalizing behavior, ADHD, ASD, developmental delay, and poorer cognition.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 As this mediation was partial, additional mechanisms explaining why children of mothers with overweight/obesity are less likely to fully master the age-appropriate developmental milestones skills, and why infants with higher levels of regulatory behavior problems fare worse on this developmental milestones measure, still remain to be determined. The mechanisms may be partly shared, as there exists some evidence suggesting that the roots of both regulatory behavior problems in infancy and neurodevelopmental adversity in childhood may be related to abnormal insulin/IGF-I signaling in the fetal brain,32 changes in the maternal microbiota,33,34 and DNA methylation35,36 caused by maternal overweight/obesity.

Other underlying mechanisms that may underpin the direct and indirect effects of maternal overweight/obesity on infant regulatory behaviors and developmental milestones may relate to placental function.37 We have demonstrated in a subsample of the PREDO study participants that higher placental glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, and serotonin gene expression levels are associated with higher levels of infant regulatory behavior problems.23 These gene expression levels are also associated with maternal pre-pregnancy BMI.38 In addition, oxidative stress in the placenta in women with obesity alters cell membranes by increasing the incorporation of cholesterol and oxidized free fatty acids and low-density lipoproteins,39,40 inducing fetal epigenetic reprogramming.41 Further, increased maternal levels of cytokine interleukin-6, the production of which is higher in the presence of obesity,42 can cross the placenta, and may disrupt normal fetal brain development.

An inherent strength of our study is related to our study design: over 20% of the participants were recruited based on their identified risk factor status for preeclampsia and suboptimal fetal growth. These recruitment criteria led to a higher prevalence of maternal overweight/obesity, hypertensive disorders, and GDM in our study sample and gave us increased statistical power to examine their specific and independent effects. By conducting analyses that excluded women with hypertensive disorders and GDM, we were able to completely eliminate their possible confounding and modifying effects, and show the independent effects of maternal overweight/obesity on infant regulatory behavior problems. The other strengths of our study include the prospective study design, and deriving exposure data from the MBR and medical records. For a subsample, these data were further verified by a clinical jury. Also, in contrast to most previous studies, objective measurements of maternal weight and height were conducted at the first antenatal clinic visit, which took place in early pregnancy. We also benefited from having a large study sample. In addition, we were able to adjust for several possible confounders that we expected to predict infant regulatory behaviors. These factors included maternal age at delivery, mode of delivery, parity, maternal smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, maternal education, and child’s gestational age and birthweight. In contrast, the study limitations include the fact that neonatal regulatory behaviors and developmental milestones data were mother-reported. This may have introduced an information bias. To overcome any potential bias in reporting regulatory behavior problems, the mothers were asked to rate regulatory behaviors they would expect an “average” infant to display and then rate her own infant.23 The majority of previous studies have also used mother reports or parent reports of infant regulatory behavioral challenges, as we did. Neurologists’ assessments have been used in some studies, but these assessments usually concern oral motor functioning in relation to feeding problems.4 Hence, the use of mother reports remains a limitation, as long as gold standards do not exist on how to measure regulatory behavioral challenges in infancy more objectively. Previous research has also found that the ASQ is a reliable and well-validated instrument to assess child developmental milestones, demonstrating high sensitivity and specificity to screen the children in need of additional developmental assessment, monitoring, or special education.24,25 Further limitations of our study include the follow-up attrition, which was also associated with maternal characteristics. The participating mothers were older at delivery and more often primiparous than the mothers who did not participate. However, this selective attrition should not cause a bias, unless the associations between maternal overweight/obesity and infant regulatory problems would differ between participants and nonparticipants. Furthermore, while we could control for a number of potential confounders, there remains the chance of residual confounding by unmeasured factors.

In sum, our study showed that infants of overweight/obese mothers displayed higher levels of regulatory behavior problems and were more likely to display problems on multiple areas of behavioral self-regulation. Regulatory behavior problems partially mediated the effects of maternal overweight/obesity on childhood developmental milestones. Our findings suggest that prevention of overweight/obesity in women of childbearing age will benefit the offspring by reducing the burden of regulatory problems in infancy and preventing their long-term neurodevelopmental consequences.

References

Hemmi, M. H., Wolke, D. & Schneider, S. Associations between problems with crying, sleeping and/or feeding in infancy and long-term behavioural outcomes in childhood: a meta-analysis. Arch. Dis. Child 96, 622–629 (2011).

Becker, K. et al. Are regulatory problems in infancy precursors of later hyperkinetic symptoms? Acta Paediatr. 93, 1463–1469 (2004).

Liu, J. et al. Neonatal neurobehavior predicts medical and behavioral outcome. Pediatrics 125, e90–e98 (2010).

Schmid, G. et al. A prospective study on the persistence of infant crying, sleeping and feeding problems and preschool behaviour. Acta Paediatr. 99, 286–290 (2010).

Thunstrom, M. Severe sleep problems in infancy associated with subsequent development of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder at 5.5 years of age. Acta Paediatr. 91, 584–592 (2002).

Wolke, D., Rizzo, P. & Woods, S. Persistent infant crying and hyperactivity problems in middle childhood. Pediatrics 109, 1054–1060 (2002).

Barnevik Olsson, M. et al. Autism before diagnosis: crying, feeding and sleeping problems in the first two years of life. Acta Paediatr. 102, 635–639 (2013).

Wolke, D. et al. Crying and feeding problems in infancy and cognitive outcome in preschool children born at risk: a prospective population study. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 30, 226–238 (2009).

Rao, M. R. et al. Long term cognitive development in children with prolonged crying. Arch. Dis. Child 89, 989–992 (2004).

Bilgin, A. & Wolke, D. Regulatory problems in very preterm and full-term infants over the first 18 months. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 37, 298–305 (2016).

Goldenberg, R. L. et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 371, 75–84 (2008).

Rodriguez, A. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and risk for inattention and negative emotionality in children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 51, 134–143 (2010).

Jo, H. et al. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and child psychosocial development at 6 years of age. Pediatrics 135, e1198–e1209 (2015).

Krakowiak, P. et al. Maternal metabolic conditions and risk for autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics 129, e1121–e1128 (2012).

Girchenko, P., et al., Maternal early pregnancy obesity and related pregnancy and pre-pregnancy disorders: associations with child developmental milestones in the prospective PREDO Study. Int. J. Obes. 42, 995–1007 (2018).

Rivera, H. M., Christiansen, K. J. & Sullivan, E. L. The role of maternal obesity in the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders. Front. Neurosci. 9, 194 (2015).

Aubuchon-Endsley, N., et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and gestational weight gain influence neonatal neurobehaviour. Matern. Child Nutr. 13:e12317 (2016).

Girchenko, P. et al. Cohort profile: prediction and prevention of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction (PREDO) study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1380–1381g (2017).

Gissler, M. Finnish health and social welfare registers in epidemiological research. Nor. Epidemiol. 14, 113–120 (2004).

Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 894 i-xii, 1–253 (2000).

Broussard, E. R. & Hartner, M. S. Maternal perception of the neonate as related to development. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 1, 16–25 (1970).

Povedano, N. & Pinheiro, G., Mother’s perceptions and expectations regarding their newborn infants: the use of Broussard’s neonatal perception inventory. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 29 vol.29, n.2 (2011).

Raikkonen, K. et al. Maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy, placental expression of genes regulating glucocorticoid and serotonin function and infant regulatory behaviors. Psychol. Med. 45, 3217–3226 (2015).

Squires, J., Bricker, D. & Potter, L. Revision of a parent-completed development screening tool: Ages and Stages Questionnaires. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 22, 313–328 (1997).

Bricker, D. et al. The validity, reliability, and cost of a parent-completed questionnaire system to evaluate at-risk infants. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 13, 55–68 (1988).

Charkaluk, M. L., et al. Ages and Stages Questionnaire at 3 years for predicting IQ at 5-6 years. Pediatrics 139 vol 139 n.4 (2017).

Hayes, A. F. & Rockwood, N. J. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 98, 39–57 (2016).

Schmid, G. et al. Predictors of crying, feeding and sleeping problems: a prospective study. Child Care Health Dev. 37, 493–502 (2011).

Wolf, M. J. et al. Neurobehavioral and developmental profile of very low birthweight preterm infants in early infancy. Acta Paediatr. 91, 930–938 (2002).

Bilgin, A. & Wolke, D. Development of comorbid crying, sleeping, feeding problems across infancy: Neurodevelopmental vulnerability and parenting. Early Hum. Dev. 109, 37–43 (2017).

Gillman, M. W. Developmental origins of health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1848–1850 (2005).

Jing, Y. H. et al. Retardation of fetal dendritic development induced by gestational hyperglycemia is associated with brain insulin/IGF-I signals. Int J. Dev. Neurosci. 37, 15–20 (2014).

Borre, Y. E. et al. Microbiota and neurodevelopmental windows: implications for brain disorders. Trends Mol. Med 20, 509–518 (2014).

Neri, C. & Edlow, A. G. Effects of maternal obesity on fetal programming: molecular approaches. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 6, a026591 (2015).

Catalano, P. M. & Shankar, K. Obesity and pregnancy: mechanisms of short term and long term adverse consequences for mother and child. Bmj 356, j1 (2017).

Nomura, Y. et al. Global methylation in the placenta and umbilical cord blood from pregnancies with maternal gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and obesity. Reprod. Sci. 21, 131–137 (2014).

Cuffe, J. S. M. et al. Review: placental derived biomarkers of pregnancy disorders. Placenta 54, 104–110 (2017).

Raikkonen, K. et al. Associations between maternal level of education and occupational status with placental glucocorticoid regeneration and sensitivity. Clin. Endocrinol. 81, 175–182 (2014).

Jauniaux, E., Poston, L. & Burton, G. J. Placental-related diseases of pregnancy: involvement of oxidative stress and implications in human evolution. Hum. Reprod. Update 12, 747–755 (2006).

Malti, N. et al. Oxidative stress and maternal obesity: feto-placental unit interaction. Placenta 35, 411–416 (2014).

Marchlewicz, E. H. et al. Lipid metabolism is associated with developmental epigenetic programming. Sci. Rep. 6, 34857 (2016).

Jonakait, G. M. The effects of maternal inflammation on neuronal development: possible mechanisms. Int J. Dev. Neurosci. 25, 415–425 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The PREDO study would not have been possible without the dedicated contribution of the PREDO Study group members: A. Aitokallio-Tallberg, A.-M. Henry, V.K. Hiilesmaa, T. Karipohja, R. Meri, S. Sainio, T. Saisto, S. Suomalainen-Konig, V.-M. Ulander, T. Vaitilo (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland), L. Keski-Nisula, Maija-Riitta Orden (Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland), E. Koistinen, T. Walle, R. Solja (Northern Karelia Central Hospital, Joensuu, Finland), M. Kurkinen (Päijät-Häme Central Hospital, Lahti, Finland), P. Taipale, P. Staven (Iisalmi Hospital, Iisalmi, Finland), and J. Uotila (Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland). We also thank the PREDO cohort mothers, fathers, and children for their enthusiastic participation. This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (K.R., grant numbers 284859, 2848591, and 312670), (E.K., grant numbers 127437, 129306, 130326, 134791, 263924, and 274794), (H.L., grant numbers 121196, 134957, and 278941), (M.L.-P., grant number 12853241), (A.-K.P.); University of Helsinki Research Funds (M.L.-P.), (H.L.), British Heart Foundation (R.M.R.); Tommy’s (R.M.R.); European Commission (E.K., K.R., Horizon 2020 Award SC1-2016-RTD-733280 RECAP); Foundation for Pediatric Research (E.K.); Juho Vainio Foundation (E.K.); Novo Nordisk Foundation (E.K.); Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation (K.R., E.K.); Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (E.K.); Finnish Medical Foundation (H.L.); Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation (H.L.); Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation (H.L.); and Doctoral Program of Psychology, Learning, and Communication (P.G.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Girchenko, P., Lahti-Pulkkinen, M., Lahti, J. et al. Neonatal regulatory behavior problems are predicted by maternal early pregnancy overweight and obesity: findings from the prospective PREDO Study. Pediatr Res 84, 875–881 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-018-0199-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-018-0199-1

This article is cited by

-

Prenatal environmental adversity and child neurodevelopmental delay: the role of maternal low-grade systemic inflammation and maternal anti-inflammatory diet

European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2023)

-

Depression, obesity and their comorbidity during pregnancy: effects on the offspring’s mental and physical health

Molecular Psychiatry (2021)