Abstract

Breast cancer is highly aggressive and is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women in developed countries. The ETS proto-oncogene 1 (Ets1) has versatile roles during the cellular processes of cancer development. It is often highly expressed in breast cancers and mediates migration and invasion of human breast cancer cells. However, underlying mechanisms of Ets1 gene expression is still ambiguous. Here, we identified a core-regulatory element (CRE) located in the Ets1 promoter region (−540/−80 bp from TSS) that contains elements responsible for associating with NFATs and NF-κBs. Compared with the less metastatic breast cancer cells, metastatic breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) show open chromatin configurations in the CRE, which facilitates direct binding of NFATc2 and/or NFKB1/RELA complex to trans-activate Ets1 transcription. Moreover, enhanced level of Nfatc2 and Nfkb1 positively correlated with Ets1 expression in the human breast cancer specimens. Deletion of the CRE region by CRISPR/Cas9 system resulted in significant reduction in Ets1 expression, which led to alterations of Ets1-mediated transcription programs including tumor invasiveness-related genes. Proper regulation of Ets1 gene expression by targeting the NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA interaction could be a potential therapeutic target for Ets1-mediated metastatic breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer cells have unique programs to potentiate tumorigenesis at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational steps1. The ETS proto-oncogene 1 (Ets1) is known as an oncogenic transcription factor. Ets1 contributes to the development and progression of diverse tumors such as epithelial tumor, sarcomas, and astrocytomas2,3,4 by directly regulating the expression of extracellular matrix remodeling factors such as MMP-1, MMP-3 and MMP-9, and uPA (urokinase-type plasminogen activator)5,6,7,8. Ets1 also promotes the angiogenic process of tumor cells by enhancing the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor, Neuropilin-1 (Nrp1), and angiopoietin-2 (Ang2)9,10,11,12. Ets1 also regulates epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in epithelial and carcinoma cells13,14. Moreover, high level of Ets1 expression was closely linked with strong metastatic potential and poor clinical prognosis in various types of cancers15,16,17. Accordingly, Ets1 could be a conceivable therapeutic target especially in the triple-negative/basal-like breast cancers (TN/BLBC) that show Ets1high expression profile compared with non-TNBC cells18.

Interestingly, however, underlying mechanisms of transcriptional regulation of Ets1 gene expression is poorly characterized in cancer cells. Previous studies were mainly focused on understanding how Ets1 expression is regulated by factors within tumor microenvironment such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB), and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ)19,20,21,22. These extrinsic factors enhance Ets1 transcription through subsequent activation of downstream signaling pathways including MEK/ERK1/2, PI3K (phosphoinositol-3-kinase)/AKT, protein kinase C (PKC), and calcium signaling19,20,21,22,23. Under such conditions, several transcription factors (such as AP-1, Ets1, and hypoxia-mediated HIF1α [HIF1α]) are known to directly upregulate Ets1 transcription in cancer cells24,25,26. However, it is still unclear which types of transcriptional factors and cis-acting regulatory elements cooperatively regulate transcriptional activity of Ets1 gene expression, especially in breast cancer cells.

In this study, we investigated the transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of Ets1 gene expression in metastatic breast cancer cells. We identified a core-regulatory element (CRE) on the Ets1 promoter and elucidated its functional importance in tumor invasiveness. Compared with less metastatic cells (MCF-7), metastatic breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) have relatively open chromatin structure on the CRE, which facilitates direct binding of NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA to enhance Ets1 expression and invasiveness of metastatic breast cancers, accordingly.

Results

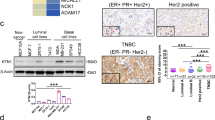

Ets1 expression is regulated at the transcriptional level in breast cancer cells

To understand the transcriptional regulation mechanisms of Ets1 expression in breast cancer cells, we first analyzed Ets1 transcript level among various breast cancer cell lines. Based on Ets1 level, cancer cells were divided into two categories: Ets1high and Ets1low cell lines (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Figures S1a, b). We chose three representative cell lines, MCF-7 (Ets1low), MDA-MB-468(Ets1low), and MDA-MB-231 (Ets1high), and confirmed the expression status of Ets1 by qRT-PCR and Immuno-blot (Fig. 1b, c) (Supplementary Figures S1a, b). Since Ets1 expression is correlated with invasiveness of tumor cells27, we compared the invasive properties of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 by invasion assay. Indeed, MDA-MB-231 (Ets1high) cells were more invasive than MCF-7 (Ets1low) cells (Fig. 1d). To confirm this observation is Ets1-dependent, we compared non-metastatic MDA-MB-468 cells with MDA-MB-231 cells, which share similar hormonal status. Similar to the MCF-7 cells, MDA-MB-468 cells showed reduced Ets1 expression with less invasive properties than MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplementary Figures S1a, b).

a Analysis of Ets1 expression profile in 59 breast cancer cell lines by Cancer Cell Lines Encyclopedia (CCLE). b, c Analyses of Ets1 transcripts and protein levels by qRT-PCR (b) and Immuno-blot (c) in unstimulated condition. d Cells were stained with crystal violet and representative images were obtained from in vitro invasion assay using 10% FBS as chemoattractant. Scale bar: 100 m. e Metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with indicated stimuli for 6 h and relative levels of Ets1 transcripts normalized against Hprt are shown. f Effect of PMA (p), Ionomycin (i) and their combination (p/i) on Ets1 transcripts levels determined by qRT-PCR. g, h Comparative analysis of Ets1 transcripts and protein level between the cells in response to PMA/Ionomycin (p/i) stimulation. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests showed a significant difference of Ets1 expression. i Effect of actinomycin D (Act D) treatment in MDA-MB-231 cells on Ets1 transcripts and protein levels determined by qRT-PCR and Immuno-blot, respectively. Values in b, d, f, e, and i are means ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction indicated a significant difference. b–i Data shown are representative of more than three independent experiments with similar results. N.D. not detected. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001

Next we tested which types of stimuli trigger Ets1 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. To mimic tumor microenvironment (TME), MDA-MB-231 cells were stimulated with various tumorigenic factors such as TGFβ, HGF, and PMA and Ionomycin28,29,30. Co-treatment with PMA and Ionomycin (P/I) induced the highest level of Ets1, indicating synergy between PKC and calcium (Ca2+) pathways (Fig. 1e, f). Compared with MCF-7 cells, MDA-MB-231 cells showed significantly enhanced Ets1 expression in mRNA and protein levels upon PMA/Ionomycin stimulation (Fig. 1g, h). Treatment of the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D abolished PMA/Ionomycin induced Ets1 expression, indicating that Ets1 expression is regulated at the transcriptional level in the metastatic MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (Fig. 1i).

Identification of core-regulatory element (CRE) and CRE-binding transcription factors involved in Ets1 expression

To identify the core-regulatory element (CRE), we serially deleted the Ets1 promoter region and tested its effect on trans-activation of Ets1 expression measured by reporter activity. As shown in Fig. 2a, deletion of −540 to −80 bps from transcription start site (TSS) significantly reduced the luciferase activity, indicating the pivotal role of this locus for the trans-activation of Ets1 expression. Using an ECR browser31, we identified NFATs and NF-κB transcription factors could potentially bind to this locus to activate Ets1 expression (Supplementary Figures S2a, b). Indeed, among the diverse transcription factors tested, co-transfection of NFATc2 or NFKB1/RELA resulted in highest Ets1 promoter activity (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Figure S2c). In contrast, mutations of NFAT or NF-κB binding sequences completely abrogated Ets1 promoter activity (Fig. 2c). We also confirmed that knockdown (KD) of these factors (Nfatc2, Nfkb1, and Rela) significantly reduced Ets1 expression (Fig. 2d–f). Moreover, triple knockdown (TKD) of these factors most significantly reduced Ets1 expression (Fig. 2e, f) and decreased the invasive properties of MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2g). These results indicate NFATc2, NFKB1 and RELA cooperatively enhance Ets1 expression through CRE (−80 to −520bps from TSS) region in the metastatic MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells.

a Schematic diagram of the genomic position and size of the deletion constructs of promoter region of Ets1 gene are shown. b MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with Ets1 promoter-Luc reporter vector (540 bp) and together with indicated combinations (minus, plus) of expression vectors. Relative luciferase activity was measured. c MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with Ets1 promoter-Luc (540 bp) vector or vectors mutated in the NFAT or NFAT/NFKB binding sites (multiply: mutation site). Relative luciferase activity in response to PMA/Ionomycin stimulation was measured. b, c Relative luciferase activities relative to the expression of Renilla luciferase plasmid (hRluc) are calculated as fold difference relative to the control value. d, e Effects of knockdown of indicated transcription factors on the expression of Ets1. MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with mock siRNAs or siRNAs for indicated transcription factors (NFATc2, NFKB1 and RELA) (d) or triple combination of them (TKD) (d, e). Knockdown efficiency on the level of transcription factors by individual siRNAs or TKD siRNAs was confirmed by Immuno-blot (f) and band intensity of Immuno-blot was quantified by ImageJ software. g Knockdown of individual siRNAs or TKD siRNAs on invasive properties of MDA-MB-231 cells by invasion assay. Scale bar: 100 m. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction indicated a significant difference of invaded cells. a–c, f Data are presented as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests showed a significant difference. a–g Data shown are representative of more than three independent experiments with similar results. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001

NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA regulate Ets1 expression in metastatic breast cancer cells

To gain further mechanistic insight on the role of NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA on Ets1 expression in MCF-7 (Ets1low) and MDA-MB-231 (Ets1high) cells, we next compared the expression status of NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA in these cell lines. MDB-MB-231 cells expressed much higher levels of NFATc2 in mRNA and protein (total and nuclear) compared with MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3a, b, d). On the other hand, no significant differences were observed in NFKB1 and RELA levels between these cells (Fig. 3a, b). Similar to MCF-7 cells, non-metastatic triple-negative MDA-MB-468 cells showed reduced expression of NFATc2 levels and invasion related genes including Eng and Mmp14 compared to MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplementary Figures S1c, d).

a, b Comparison of NFATc2, NFKB1, and RELA protein and transcript levels in whole cell lysates of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells determined by a Immuno-blot and b qRT-PCR normalized against Hprt. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction indicated a significant difference of expression. c Scatterplots and Spearman’s rank correlation from TCGA database. Correlation between mRNA expression of Ets1 with Nfatc2, Nfkb1, and Rela. Each symbol represents an individual human specimen. a, d Representative Immuno-blot for the total and nuclear (NE) protein levels in unstimulated conditions or cells stimulated for indicated time points. ACTIN and LaminB1 served as loading control for total and NE, respectively. e Effect of overexpression of transcription factors (NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA) on Ets1 expression in MCF-7 cells determined by Immuno-blot. f Relative enrichment of transcription factors to the CRE region determined by ChIP analysis with specific antibodies for NFATc2, NFKB1, and RELA. Results are presented relative to input DNA. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests showed a significant difference of binding efficiency of NFATc2, NFKB1, and RELA between MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. a, b, d, e, f Data shown are representative of more than three independent experiments with similar results. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test)

Next, we tested whether differential expression of NFATc2 or NF-κBs has any correlation with Ets1 expression in human breast cancer specimens by analyzing The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database that provide unbiased large-scale transcriptome data for various human cancer32. Indeed, expression level of Nfatc2 (Spearman r = 0.5183, ***p < 0.0001) and Nfkb1 (Spearman r = 0.3276, ***p < 0.0001) but not Rela showed correlative expressions with Ets1 levels in human specimens (Fig. 3c). We also compared nuclear levels of NFATc2, NFKB1, and RELA levels between the cells. Compared with MCF-7 cells (Ets1low), MDA-MB-231 (Ets1high) cells showed significantly higher levels of NFATc2, NFKB1, and RELA in the nucleus upon PMA/Ionomycin stimulation (Fig. 3d). Forced expression of NFATc2, NFKB1/RELA in MCF-7 cells significantly enhanced Ets1 expression and invasiveness (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Figure S3a). Overexpression of Ets1 also enhanced the invasive capacity of MCF-7 cells (Supplementary Figure S3b). Next, we performed ChIP assay to measure the binding of these factors to CRE region between the cells. Compared with MCF-7 cells (Ets1low), MDA-MB-231 (Ets1high) cells showed higher binding of NFATc2 as well as NFKB1/RELA to the CRE region (Fig. 3f). In addition, overexpression of NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA increased the binding of these factors to the CRE region in MCF-7 cells (Supplementary Figure 3c). These results suggest that cellular availability as well as relative enrichment of NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA to the CRE region mediate differential Ets1 expression between MDA-MB-231 (Ets1high) and MCF-7 cells (Ets1low).

Permissive chromatin architecture at the promoter is required for Ets1 expression

Epigenetic abnormality in various cancer-related genes is often involved in enhanced tumorigenesis33,34. To compare the chromatin architecture between the MDA-MB-231 (Ets1high) and MCF-7 cells (Ets1low), we have performed chromatin accessibility by real-time PCR (CHART-PCR). Compared with MCF-7 cells (Ets1low), MDA-MB-231 (Ets1high) cells showed more open chromatin structure at the Ets1 promoter region (Supplementary Figure S4a). Next we compared epigenetic status of histone modification and DNA methylation between the cells. First we analyzed ChIP-seq data set35 for H3K27Ac (active chromatin) and H3K27me3 (inactive chromatin) in the Ets1 genomic locus between the cells. Compared to MCF-7 cells, MDA-MB-231 cells showed highly enriched H3K27Ac but decreased levels of H3K27me3 (Fig. 4a). By performing ChIP analysis, we confirmed that the Ets1 locus in MDA-MB-231 cells is enriched for chromatin modifications associated with active gene transcription (H3Ac). On the other hand, chromatin modifications associated with repressed gene expression are under-represented (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) (Fig. 4b).

a ChIP-seq analysis of H3K27Ac and H3K27me3 at Ets1 promoter locus in MCF-7 (blue line) and MDA-MB-231 (red line) cells. b ChIP analysis of active marker (H3Ac) and inactive markers (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) at Ets1 promoter locus under unstimulated or P/I stimulation conditions. The data from each replicate were normalized to the input control and the graphs represent fold enrichment of the indicated proteins to control antibody at the designated locus. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests showed a significant difference of binding efficiency of H3Ac, H3K9me3, and H3K27me3 between MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. c DNA methylation status in the nine CpG sites (−375 or −534) was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing under unstimulated or stimulated (P/I) condition. Closed and open circles indicate methylated and unmethylated CpG sites, respectively. Bar graphs represent percentage methylation. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests showed a significant difference of DNA methylation status. d Heatmap of RNA-sequencing data showing relative expression of DNA methylation-related and demethylation-related factors. e Analysis of relative expression levels in transcripts normalized against Hprt and proteins by qRT-PCR and Immuno-blots, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction indicated a significant difference of expression. f Scatterplots and nonparametric Spearman’s rank correlation (ρ) analysis with corresponding p-values correlation analysis from CCLE. Correlation between Ets1 and DNA methylation-related genes (Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b, and Apobec3c) in mRNA. Each symbol represents an individual human breast cancer cell line. Green circle: MCF-7 cells; Red circle: MDA-MB-231 cells. b, c, e Data shown are representative of more than two independent experiments with similar results. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test)

Since DNA methylation is another epigenetic mechanism to control gene expression36, we compared DNA methylation status of individual CpG sites localized in CRE by bisulfide sequencing. All of nine CpG sites were highly methylated in MCF-7 but demethylated in MDA-MB-231 regardless of PMA/Ionomycin stimulation (Fig. 4c). We tested whether treatment of Decitabine (a DNA methyl-transferase inhibitor) or TSA (a HDAC inhibitor) could enhance Ets1 expression in MCF-7. Decitabine but not the TSA treatment enhanced Ets1 expression in MCF-7 (Supplementary Figures S4b, c). Moreover, Decitabine treatment increased invasiveness of MCF-7 cells and enhanced the binding efficiency of NFKB1 and RELA to CRE region (Supplementary Figures S4d, e). These results collectively suggest that chromatin architecture at the Ets1 promoter (CRE region) in MCF-7 cells is in a “less permissive” but not a “non-permissive” state.

To test whether differential DNA methylation status between the cells is due to changes in level of DNA methyl transferases, we analyzed a publicly available RNA-seq data set37. Compared with MDA-MB-231 cells, MCF-7 cells were found to express significantly higher levels of DNA methyl-transferase (Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b) but lower levels of APOBEC family genes (Fig. 4d, e). APOBEC is known as a cytidine deaminases and its dysregulation causes mutations in numerous cancer types. Furthermore, MCF-7 cells showed higher binding of DNMT3A and DNMT3B on CRE region (Supplementary Figure S5a) while MDA-MB-231 cells show no DNMT association to Ets1 locus due to their low expression (data not shown). We also tested whether levels of Ets1 expression could be altered upon overexpression of DNMT3A/3B or APOBEC3C in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells, respectively. Indeed, overexpression of DNMT3A/3B in MDA-MB-231 cells decreased Ets1 expression, whereas overexpression of APOBEC3C in MCF-7 cells slightly increased Ets1 expression (Supplementary Figures S5b, c). These results in part suggest availability of DNA methyl transferases can affect the level of Ets1 transcription.

We also questioned whether this finding could be generalized in various breast cancer cell lines (n = 59). Indeed, analysis of Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia confirmed that Ets1 expression was negatively correlated with Dnmt3a (Spearman r = −0.4139, **p = 0.0011) and Dnmt3b (Spearman r = −0.5878, ***p < 0.0001) but positively with Apobec3c (Spearman r = 0.6239, ***p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4f). Consistent with human cell line data, Ets1 expression was negatively correlated with Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b in normal specimens, while Ets1 level is positively correlated with Apobec3c in human breast cancer specimens (Supplementary Figure S5d). These results indicate that Ets1 expression is epigenetically regulated in breast cancer.

Deletion of CRE region reduces Ets1 expression and tumor invasiveness

To validate the functional role of NFAT and NF-κB binding sites (−540bp to −270bp) within the CRE region (−540 to −80 from TSS) in Ets1-mediated tumorigenesis, we deleted the region by a CRISPR/Cas9 based KO system in metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplementary Figures S6a, b). Compared with wild-type MDA-MB-231 cells (WT), CRE-deleted cells (ΔCRE) showed lower levels of Ets1 expression in mRNA and protein (Fig. 5a, b). We then compared transcriptome profiles between WT and ΔCRE cells by RNA-seq analysis. ΔCRE cells showed altered expression of numerous genes (DEGs: p-value < 0.05; 0 h - Up: 285 and Down: 179, 6 h - Up: 627 and Down: 954, 24 h - Up: 544 and Down: 745) (Fig. 5c). Gene-annotation enrichment analysis (DAVID) showed that ΔCRE cells had alterations in cell adhesion and angiogenesis programs (Fig. 5d). Indeed, we found that ΔCRE cells express much lower level of Eng and Mmp14 (Fig. 5e), critical factors for cell adhesion38,39. In addition, by performing ChIP assay, we confirmed the possibility that direct binding of Ets1 to the promoters of those target genes regulates expression levels (Fig. 5f). Analysis of human breast cancer specimens further confirmed this possibility. We analyzed 1000 human breast cancer specimens (Fig. 5g) and 59 human breast cancer cell lines (Fig. 5h) and found that levels of Ets1 expression is well-correlated with Eng and Mmp14 levels, accordingly (Fig. 5g, h).

a, b Comparative analysis of Ets1 expression levels in transcripts and protein between WT and CRE-deleted MDA-MB-231 (ΔCRE) cells determined by qRT-PCR and Immuno-blot. Transcript levels were normalized against Hprt and actin served as loading controls, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests showed a significant difference of Ets1 expression. c Heatmap of RNA-sequencing data showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in WT and ΔCRE MDA-MB-231 cells. d GO-term enrichment using DAVID “Biological functions” category. Shown are the top five up and down-regulated functions based on –log2(p value). e Comparison of expression levels of Ets1 target genes between WT and ΔCRE cells. f ChIP-PCR was performed to detect Ets1 enrichment on the promoter regions of Eng and Mmp14 genes in MDA-MB-231 cells 2 h after stimulation. Fold enrichment compared with input is shown. Data are representative of two individual experiments. Bars represent averages from triplicate PCR reactions as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction indicated a significant enrichment of Ets1; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. g Scatterplots and nonparametric Spearman’s rank correlation analysis with corresponding P-values correlation analysis from TCGA. Correlation between Ets1 and target genes (Eng and Mmp14) in mRNA levels. Each symbol represents an individual BRCA sample. h Scatterplots and nonparametric Spearman’s rank correlation analysis with corresponding p-values correlation analysis from CCLE. Correlation between Ets1 and target genes (Eng and Mmp14) in mRNA levels. Each symbol represents an individual human breast cancer cell line. i Cells were stained with crystal violet and representative images were obtained from in vitro invasion assay using 10% FBS as chemoattractant. Cells were stained with crystal violet. Scale bar: 100 m. j Representative images (left) and numbers of metastasis nodules (right) of mouse lungs obtained from 6 weeks after tail vein injections of WT or ΔCRE cells (each 5 × 105) into eight female nude mice, respectively. i, j Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction indicated a significant difference between WT and ΔCRE cells. a, b, e, f, i, j Data shown are representative of more than two independent experiments with similar results. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test)

To verify the functional role of CRE in Ets1-mediated metastasis of breast cancer cells, first we performed in vitro invasion assay. Compared with WT MDA-MB-231, ΔCRE cells showed significantly reduced invasive capacity (Fig. 5i). To further confirm whether CRE deletion reduces tumor invasiveness in vivo, nude mice were injected intravenously into the tail vein with either ΔCRE or WT MDA-MB-231 cells. After 6 weeks, tumor invasiveness was compared between the groups. Indeed, ΔCRE-injected mice showed a significant reduction of metastasis nodules in the lungs compared with mice injected with WT cells (Fig. 5j). Interestingly, Ets1 overexpression in ΔCRE cells significantly increased their invasive properties but was still less compared to the parent WT MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplementary Figures S7a, b). Moreover, overexpression of both NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA into ΔCRE cells increased Ets1 expression and their invasive properties, but was still less compared to the WT MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplementary Figures S7c, d). Collectively, these data demonstrate a critical role of CRE in Ets1 gene expression and Ets1-mediated metastasis of breast cancer cells.

Discussion

In this study, we have found that Ets1 gene expression is regulated epigenetically as well as by the crosstalk between NFATc2/NF-κBs and core-regulatory element (CRE) located in the Ets1 promoter. Deletion of CRE region down-regulated Ets1 expression and, consequently, reduced breast cancer progression by altering cancer-associated genetic programs.

Ets1 expression and function are regulated by diverse mechanisms. Previous studies reported that Ets1 gene expression is transcriptionally regulated by several transcription factors including Ets1, AP-1, AP-2, and Oct in human T cell and B cell lines24,40,41. In this study, we identified the core-regulatory element (CRE) region in the Ets1 promoter that contains binding sequences for NFATs and NF-κBs. Binding of NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA heterodimer to the CRE region synergistically contribute to the expression of Ets1. NFATs and NF-κBs factors are reported as downstream targets of calcium and PKC signaling, respectively, and affect expression level of their target genes associated with tumor pathogenesis42,43,44,45,46,47. Our finding support the previous reports that calcium signaling affects multiple cellular responses in the tumor microenvironment48,49. Ca2+-NFAT signaling is associated with growth and development of malignant breast cancer43. Ca2+ ionophore, ionomycin synergizes with PMA in enhancing the activation of PKC50. In accordance with this notion, we observed that Ets1 expression was synergistically increased upon PMA/Ionomycin (P/I) stimulation (Fig.1f).

Physical binding of transcription factors to the regulatory region requires permissive chromatin architecture. Moreover, epigenetic changes including aberrant DNA methylation are tightly linked to cancer development51. For example, DNMT3A mutation significantly reduced methylated DNA levels and reduced survival rate in AML patients by causing enhanced expression of HOXB genes52. Furthermore, alteration in APOBEC expression level also caused increased frequencies of TP53 mutation derived-inactivation in breast cancer development53. Although Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)/APOBEC cytosine deaminases have been shown to implicate in active DNA demethylation54, it is not clear whether aberrant DNA demethylation causes uncontrolled gene regulation in cancer development. We found that metastatic MDA-MB-231 (Ets1high) cancer cells have active chromatin status in the Ets1 locus compared to less metastatic MCF-7 (Ets1low) cells. These findings suggested that changes in level of epigenetic regulators regulate Ets1 expression. DNA methylation and demethylation are mediated by DNA methyl-transferase enzymes (DNMT1, 3A, and 3B) and TET enzymes (TET1, 2, and 3)/DNA deaminase (AID/APOBEC family), respectively. In depth analysis of gene expression profiles showed that indeed, MCF-7 (Ets1low) cells express much higher levels of DNA methyl-transferase such as Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b, while Apobec3c levels were increased (Fig. 4d, e). Based on these findings, we believe that levels of DNMT3A and DNMT3B regulate methylated status of CRE region, leading to differential Ets1 expression between metastatic versus less metastatic cells.

Deletion of NFAT and NF-κB binding sites (−540 bp to −270 bp from TSS) within the CRE region (−540 to −80) in metastatic breast cancer cells (ΔCRE cells) diminished Ets1 levels and reduced expression levels of invasion related genes. Gene ontology analysis shows that ΔCRE cells showed a significant alteration in the levels of ‘cell adhesion’ and ‘angiogenesis’ such as Nrp2, Pik3cg, Mmp14, Eng, Adam8 and Adam15 (Fig. 5c, d). In particular, we found that Ets1 directly regulates Eng and Mmp14 expression by binding to their cis-regulatory regions (Fig. 5e, f). Eng encodes Endoglin/CD105, a co-receptor for transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family. Endoglin (ENG) is known as a critical factor for tumor invasion by enhancing formation of invadopodia, extracellular proteolysis, chemotaxis, and migration55. Elevated ENG in breast tumor tissue is associated with higher metastatic risk and poor prognosis56,57. In addition, ΔCRE cells showed a significant alteration in the levels of matrix metalloproteinase MMP14 that has an important role in tumor invasion by regulating the levels of collagens, extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins and factors involved in epithelial–mesenchymal transition38,58,59. These findings suggest that binding of NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA to the CRE might be a key mechanism for enhanced Ets1 expression and increased invasive properties of metastatic breast cancers. However, we could not rule out other possibilities involved in this process. Indeed, overexpression of NFATc2, NFKB1/RELA in ΔCRE cells partially restored Ets1 expression and invasiveness (Supplementary Figures. S7c, d). These results suggest that within the CRE region, other region in the Ets1 promoter may also contain responsive sequences for NFATc2, NFKB1/RELA. Indeed, we found conserved NFATs/NFkB binding motifs encompassing −80/−270bp region. Reporter assay showed this region has promoter activity, which was enhanced upon stimulation (Fig. 2a). Another possibility is that NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA may regulate invasiveness of cancer cells in an Ets1-independent manner. Indeed, NFATs are known to promote invasion by inducing Cox2 expression60. NFKB also affects invasiveness of breast cancer cells by regulating CD44 level61.

In summary, our study suggests that the crosstalk between NFATc2, NFKB1/RELA, and CRE region regulates Ets1 gene transcription in metastatic breast cancer cells. Inhibition of this interaction could be a therapeutic approach to reduce Ets1 levels and Ets1-mediated tumor invasiveness of breast cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, plasmid, and reagents

Cells were cultured in DMEM (WELGENE: LM 001–05) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco: 10099–141) and 100 U/ml of penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo: 15140122). Cells were harvested with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco: 25300–054). Ets1 promoter region (hEts1, 1500 bps) was amplified with cDNA from MDA-MB-231 cells and inserted into pXPG vector. From this template, different deletion constructs were prepared by PCR and cloned into pXPG vector as shown in Fig. 2a. NFAT and/or NF-κB binding sites in Ets1 promoter were mutated by QuikChange XL Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent: #200517). hEts1 promoter-ΔNFAT-Luc, or ΔNF-κB-Luc were constructed by introducing mutations at the consensus NFAT site (TTTTAA → TTCCCGA), or NF-κB site (TTGGAA → TTAAGGA), respectively. All sequences were verified by Sanger sequencing. The following chemicals were used; phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Calbiochem: 524400), Ionomycin (Calbiochem: 407950), Cyclosporin A (Calbiochem: 239835), Decitabine (Selleckchem: 2353–33–5), and Trichostatin A (Selleckchem: 58880–19–6). All plasmids were obtained from Addgene (WT-NFAT1: #11100, pREP-NFAT2: #11788, pREP-NFAT3: #11789, pREP-NFAT4: #11790, pEGFP NFAT5: #13627, pCMV4-p50: #21965, pCMV4-p52: #23289, pcDNA-FLAG-REL: #27253, GFP-RelA: #23255, pcDNA3/Myc-DNMT3A: #35521, pcDNA3/Myc-DNMT3B1: #35522 and pcDNA3.1 human A3C: #105047).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Ohio) following standard protocols. Reverse transcription of 1.0ug of RNA was performed using oligo (dT) primer (Promega: C1101) with Improm II Reverse Transcription system (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Dye mix (Takara: RR420) on Rotor-Gene Q (Qiagen, Hilden). Data were normalized to human hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT). Primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Luciferase reporter assays

Luciferase reporter plasmids containing various regions of Ets1 promoter were co-transfected with indicated expression plasmids (such as NFATc2, NFKB1, RELA, AP-1, and Ets1) in MDA-MB-231 cells using Gene Expresso (Excellgen: EG-1086) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Renilla luciferase was co-transfected as an internal control for transfection. After 24 h of transfection, cells were harvested and luciferase activity was measured by the dual luciferase assay system (Promega: E1910) similar to a previous study62.

Nuclear extraction and immuno-blot

Whole cell lysates were extracted using RIPA buffer and nuclear/cytoplasmic fractions were isolated using nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Thermo: 78833) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Protein concentration was measured by Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad: #5000001) and 20 μg or 30 μg of proteins were used for SDS-PAGE (10%), and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad: 162–0097). The following primary antibodies were used from Abcam (Cambridge, UK): anti-NFATc2 (ab2722), anti-NFKB1 (ab7971), anti-RELA (ab7970), anti-DNMT3A (ab13888), anti-DNMT3B (ab13604) and anti-ACTIN (ab3280); Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA): anti-Ets1 (sc-350); Cell signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA): LaminB1 (#12586); GeneTex (Irvine, TX, USA): APOBEC3C (GTX102164). Protein expression was visualized with an ImageQuant™ LAS 4000 (GE healthcare Life Science, Piscataway, NJ). Actin and LaminB1 expression were measured as loading controls for whole-cell lysates, and nuclear protein, respectively. Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH).

Transfection of expression vectors and siRNAs

siRNA-mediated depletion was accomplished using Scrambled negative control (SR30004), siRNAs for NFATc2 (SR303150), NFKB1 (SR303161) and RELA (SR304030) purchased from Origene (OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD) using lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen: 13778–100) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 h, transfected cells were used for the further experiments. Plasmids for NFATc2, NFKB1, and RELA were transfected into MCF-7 cells using Gene Expresso (Excellgen: EG-1086) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-PCR assay

ChIP-PCR assays were performed by Simple ChIP plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling: #9005) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were cross-linked with 1% of formaldehyde and lysed for nuclei preparation. Nucleus pellet was treated with Micrococcal nuclease and sonicated for chromatin fragmentation. Protein–chromatin complex was incubated with antibodies targeting anti-NFATc2 (ab2722), anti-NFKB1 (ab7971), anti-RELA (ab7970), anti-DNMT3A (ab13888), anti-DNMT3B (ab13604), anti-H3K4me1 (ab8895), anti-H3K4me3 (ab8580), anti-H3K9me3 (ab8898), anti-Ets1 (Cell Signaling: #14069), anti-H3Ac (Merck: 06–599), or anti-H3K27me3 (Merck: 07–449) at 4 °C for overnight. Rabbit or mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories) was used as negative control. After immunoprecipitation, 50 μl of Dynabeads protein G or A (Life technologies, Oslo) were added and rotated further for 6 h at 4 °C. Ab/protein/chromatin complexes were reverse-cross-linked at 65 °C overnight and DNA was purified by DNA purification columns (Cell Signaling: #10010). The relative enrichment of specific regions of precipitated DNA were measured by real-time PCR (qPCR). To quantify protein binding in specific genomic locus, purified DNA was used for real-time PCR. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 2. H3K27Ac, and H3K27me3 ChIP-seq data set (GSE38548) were re-analyzed35.

Bisulfite treatment and pyrosequencing

DNA methylation analysis was performed by bisulfite pyrosequencing. Briefly, genomic DNA (200 ng) was subjected to bisulfite treatment with EZ DNA methylation-Lightning Kit (Zymo Research: D5030). Bisulfite-treated DNA was amplified using specific primers (Supplementary Table 3) with PCR premix (Enzynomics, Korea); PCR conditions: denaturing at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, at 55 °C for 30 s, at 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, sequencing was performed on a PyroMark ID system (Qiagen) with the Pyro Gold reagent kit (Qiagen: #40–0045). Unmethylated/Methylated control DNA (Qiagen: #59568/59655) was used as a negative or positive control.

Chromatin accessibility analysis

Chromatin accessibility was analyzed by EpiQuik Chromatin Accessibility Assay Kit (Epigentek: #P-1047) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, chromatin from MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells was treated with a nuclease (Nse) mix for 2 min. Nse-treated and No-Nse control DNA were amplified by quantitative PCR with primers targeting specific region on Ets1 promoter (Supplementary Table 2). Fold enrichment (FE) was calculated by using the formula FE = 2 (Nse CT-no-Nse CT) 100%.

Deletion of CRE region by CRISPR/Cas9 based KO system

To delete the NFAT and NF-κB binding sites (−540 bp to −270 bp from TSS) within the core-regulatory element (CRE; −540 to −80), guide RNA (gRNA) was designed and mismatch sensitive nuclease assay (T7E1 assay) was performed for gRNA screening as described previously63. After screening gRNA, MDA-MB-231 cells were transiently transfected with Cas9 plasmid, gRNA F and gRNA R with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). gRNA sequence were as follows: F: 5′-ACGCAGGAGCATTACATGGGTGG-3′; R: 5′-GGAGCAGTGCGTGGAGCCCC GGG-3′. After 48 h of transfection, target deleted clones were screened via genomic DNA analysis. Genomic DNA was analyzed by PCR and DNA sequencing for selecting promoter deleted cells. The primer pairs used for PCR analysis were F: 5′-CAAAGCGAAAGGAAGGGCTG-3′; R: 5′-GGAGGTAAATTGGAAGCTTACGG-3′. Mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing and the effect of CRE deletion on Ets1 level was tested by immuno-blot.

In vitro invasion assay and analysis of lung metastasis in vivo

For in vitro invasiveness assay, trans-well chamber (8 m pore size; Corning: 354578) and Matrigel (Corning: 354234)-coated membrane were used. Briefly, cells (2.5 × 104) were seeded in upper chamber containing serum-free medium and serum-containing medium in lower chamber as a chemoattractant. After 12 h of incubation, cells on the lower surface of the membrane were fixed and stained with the 0.5% crystal violet stain solution to calculate total number of invaded cells. For lung metastasis assay in vivo, WT or ΔCRE MDA-MB-231 cells (1 × 106) were intravenously injected into tail vein of 7-week-old nude mice. No blinding test was done in this study. The injected mice were killed after 6 weeks to analyze metastasis in lung. The lungs were fixed in picric acid overnight and the tumor colonies were counted under a dissection microscope. Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guide-lines and regulations, and with the approval of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at POSTECH.

RNA-sequencing

RNA-sequencing was performed by NextSeq 500 Sequencing System. Total RNA was extracted and purified with RibospinTMII (GeneAll biotechnology: 314–150). RNA was subjected to library preparation with TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina: RS-122–2101~2) and RNA-sequencing was performed by NextSeq 500 Sequencing System (Illumina). Sequences were mapped to hg19 with TopHat (version 2.0.12). Estimated expression level was generated with Cufflinks (version 2.2.1) and differentially expressed genes were selected using Cuffdiff (version 2.2.1). RNA-seq was performed on two biological replicates. The set of differential expressed genes was analyzed using DAVID gene functional classification tool64. For analysis of gene expression between MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells shown in Fig. 4d, raw data from the NCBI database (GSE48213) were analyzed65.

Analysis of data set for human samples and cell lines

Data of human breast tumor specimens (n = 1100) were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). mRNA expression data (RNA Seq V2 RSEM) were obtained through cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/). The Human breast cell lines (n = 59) expression data were obtained from Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle). Spearman correlation coefficients analysis was used to evaluate the gene expression correlation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of at least three independent experiments was performed. Error bars indicates standard deviation (SD). All student t-tests performed were student two-tailed tests (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). For comparisons of more than two groups, data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and adjusted by the correction of Bonferroni. For data with more than one independent variable, two-way ANOVA was used. Data were calculated and graphed with GraphPad Prism software.

Data accessibility

RNA-seq data sets have been deposited in the GEO database with accession code GSE106634

References

Dittmer, J. The biology of the Ets1 proto-oncogene. Mol. Cancer 2, 29 (2003).

Fujimoto, J., Aoki, I., Toyoki, H., Khatun, S. & Tamaya, T. Clinical implications of expression of ETS-1 related to angiogenesis in uterine cervical cancers. Ann. Oncol. 13, 1598–1604 (2002).

Khatun, S., Fujimoto, J., Toyoki, H. & Tamaya, T. Clinical implications of expression of ETS‐1 in relation to angiogenesis in ovarian cancers. Cancer Sci. 94, 769–773 (2003).

Seth, A. & Watson, D. K. ETS transcription factors and their emerging roles in human cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 41, 2462–2478 (2005).

Behrens, P., Rothe, M., Wellmann, A., Krischler, J. & Wernert, N. The Ets‐1 transcription factor is up‐regulated together with MMP 1 and MMP 9 in the stroma of pre‐invasive breast cancer. J. Pathol. 194, 43–50 (2001).

Behrens, P. et al. Stromal expression of invasion‐promoting, matrix‐degrading proteases MMP‐1 and‐9 and the Ets 1 transcription factor in HNPCC carcinomas and sporadic colorectal cancers. Int. J. Cancer 107, 183–188 (2003).

Nakada, M., Yamashita, J., Okada, Y. & Sato, H. Ets-1 positively regulates expression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and invasiveness of astrocytic tumors. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 58, 329–334 (1999).

Park, Y. H., Jung, H. H., Ahn, J. S. & Im, Y.-H. Ets-1 upregulates HER2-induced MMP-1 expression in breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377, 389–394 (2008).

Dutta, D., Ray, S., Vivian, J. L. & Paul, S. Activation of the VEGFR1 chromatin domain an angiogenic signal-ETS1/HIF-2α regulatory axis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25404–25413 (2008).

Elvert, G. et al. Cooperative interaction of hypoxia-inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) and Ets-1 in the transcriptional activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (Flk-1). J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7520–7530 (2003).

Teruyama, K. et al. Neurophilin‐1 is a downstream target of transcription factor Ets‐1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 504, 1–4 (2001).

Hasegawa, Y. et al. Transcriptional regulation of human angiopoietin-2 by transcription factor Ets-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 316, 52–58 (2004).

Dave, N. et al. Functional cooperation between Snail1 and twist in the regulation of ZEB1 expression during epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12024–12032 (2011).

Katoh, M. & Katoh, M. Integrative genomic analyses of ZEB2: Transcriptional regulation of ZEB2 based on SMADs, ETS1, HIF1α, POU/OCT, and NF-κB. Int. J. Oncol. 34, 1737–1742 (2009).

Yamaguchi, E. et al. Ets-1 proto-oncogene as a potential predictor for poor prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 213, 41–50 (2007).

Davidson, B. et al. Ets-1 messenger RNA expression is a novel marker of poor survival in ovarian carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 551–557 (2001).

Span, P. N. et al. Expression of the transcription factor Ets-1 is an independent prognostic marker for relapse-free survival in breast cancer. Oncogene 21, 8506 (2002).

Jung, H. H. et al. Statins affect ETS1-overexpressing triple-negative breast cancer cells by restoring DUSP4 deficiency. Sci. Rep. 6, 33035 (2016).

Ozaki, I. et al. Hepatocyte growth factor induces collagenase (matrix metalloproteinase-1) via the transcription factor Ets-1 in human hepatic stellate cell line. J. Hepatol. 36, 169–178 (2002).

Tomita, N. et al. Angiogenic property of hepatocyte growth factor is dependent on upregulation of essential transcription factor for angiogenesis, ets-1. Circulation 107, 1411–1417 (2003).

Lee, K. H., Koh, S. & Kim, J.-R. Hepatocyte growth factor-mediated gastrin-releasing peptide induces IL-8 expression through Ets-1 in gastric cancer cells. Oncol. Res. Featur. Preclin. Clin. Cancer Ther. 20, 393–402 (2012).

Watanabe, D. et al. Transcription factor Ets-1 mediates ischemia-and vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent retinal neovascularization. Am. J. Pathol. 164, 1827–1835 (2004).

Naito, S. et al. Ets-1 is an early response gene activated by ET-1 and PDGF-BB in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 274, C472–C480 (1998).

Majérus, M.-A., Bibollet-Ruche, F., Telliez, J.-B., Wasylyk, B. & Bailleul, B. Serum, AP-1 and Ets-1 stimulate the human ets-1 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 2699–2703 (1992).

Seth, A. & Papas, T. The c-ets-1 proto-oncogene has oncogenic activity and is positively autoregulated. Oncogene 5, 1761–1767 (1990).

Oikawa, M. et al. Hypoxia induces transcription factor ETS-1 via the activity of hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 289, 39–43 (2001).

Singh, S., Barrett, J., Sakata, K., Tozer, R. G. & Singh, G. ETS proteins and MMPs: partners in invasion and metastasis. Curr. Drug. Targets 3, 359–367 (2002).

Lindemann, R. K., Ballschmieter, P., Nordheim, A. & Dittmer, J. Transforming growth factor β regulates parathyroid hormone-related protein expression in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through a novel Smad/Ets synergism. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 46661–46670 (2001).

Ozaki, I. et al. Induction of multiple matrix metalloproteinase genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma by hepatocyte growth factor via a transcription factor Ets-1. Hepatol. Res. 27, 289–301 (2003).

De Tata, V., Ptasznik, A. & Cristofalo, V. J. Effect of the tumor promoter phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) on proliferation of young and senescent WI-38 human diploid fibroblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 205, 261–269 (1993).

Ovcharenko, I., Nobrega, M. A., Loots, G. G. & Stubbs, L. ECR Browser: a tool for visualizing and accessing data from comparisons of multiple vertebrate genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W280–W286 (2004). suppl_2.

Network CGA.. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumors. Nature 490, 61 (2012).

Rodríguez-Paredes, M. & Esteller, M. Cancer epigenetics reaches mainstream oncology. Nat. Med. 17, 330–339 (2011).

Veeck, J. & Esteller, M. Breast cancer epigenetics: from DNA methylation to microRNAs. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 15, 5–17 (2010).

Su, Y. et al. Somatic cell fusions reveal extensive heterogeneity in basal-like breast cancer. Cell Rep. 11, 1549–1563 (2015).

Cedar, H. & Bergman, Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 295–304 (2009).

Yamamoto, S. et al. JARID1B is a luminal lineage-driving oncogene in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 25, 762–777 (2014).

Ulasov, I., Yi, R., Guo, D., Sarvaiya, P. & Cobbs, C. The emerging role of MMP14 in brain tumorigenesis and future therapeutics. Biochim. Et. Biophys. Acta 1846, 113–120 (2014).

Nassiri, F. et al. Endoglin (CD105): a review of its role in angiogenesis and tumor diagnosis, progression and therapy. Anticancer Res. 31, 2283–2290 (2011).

Jorcyk, C. L., Watson, D., Mavrothalassitis, G. & Papas, T. The human ETS1 gene: genomic structure, promoter characterization and alternative splicing. Oncogene 6, 523–532 (1991).

Chen, J., Jeha, S. & Oka, T. Negative regulatory elements in the human ETS1 gene promoter. Oncogene 8, 133–139 (1993).

Müller, M. R. & Rao, A. NFAT, immunity and cancer: a transcription factor comes of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 645–656 (2010).

Mancini, M. & Toker, A. NFAT proteins: emerging roles in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 810–820 (2009).

Staudt, L. M. Oncogenic activation of NF-κB. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000109 (2010).

Huber, M. A. et al. NF-κB is essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in a model of breast cancer progression. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 569–581 (2004).

Xie, T.-X., Xia, Z., Zhang, N., Gong, W. & Huang, S. Constitutive NF-κB activity regulates the expression of VEGF and IL-8 and tumor angiogenesis of human glioblastoma. Oncol. Rep. 23, 725 (2010).

Yoshida, A., Yoshida, S., Ishibashi, T., Kuwano, M. & Inomata, H. Suppression of retinal neovascularization by the NF-kappaB inhibitor pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate in mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40, 1624–1629 (1999).

Yang, S., Zhang, J. J. & Huang, X.-Y. Orai1 and STIM1 are critical for breast tumor cell migration and metastasis. Cancer Cell. 15, 124–134 (2009).

Wei, C. et al. Calcium flickers steer cell migration. Nature 457, 901–905 (2009).

Chatila, T., Silverman, L., Miller, R. & Geha, R. Mechanisms of T cell activation by the calcium ionophore ionomycin. J. Immunol. 143, 1283–1289 (1989).

Baylin, S. B. & Jones, P. A. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome—biological and translational implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 726–734 (2011).

Yan, X.-J. et al. Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 43, 309–315 (2011).

Burns, M. B. et al. APOBEC3B is an enzymatic source of mutation in breast cancer. Nature 494, 366–370 (2013).

Bhutani, N., Burns, D. M. & Blau, H. M. DNA demethylation dynamics. Cell 146, 866–872 (2011).

Oxmann, D. et al. Endoglin expression in metastatic breast cancer cells enhances their invasive phenotype. Oncogene 27, 3567–3575 (2008).

Kumar, S. et al. Breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 59, 856–861 (1999).

Dales, J.-P. et al. CD105 expression is a marker of high metastatic risk and poor outcome in breast carcinomas: correlations between immunohistochemical analysis and long-term follow-up in a series of 929 patients. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 119, 374–380 (2003).

Devy, L. et al. Selective inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-14 blocks tumor growth, invasion, and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 69, 1517–1526 (2009).

Yan, T. et al. MMP14 regulates cell migration and invasion through epithelial-mesenchymal transition in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Am. J. Transl. Res. 7, 950 (2015).

Yiu, G. K. & Toker, A. NFAT induces breast cancer cell invasion by promoting the induction of cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12210–12217 (2006).

Smith, S. M., Lyu, Y. L. & Cai, L. NF-κB affects proliferation and invasiveness of breast cancer cells by regulating CD44 expression. PLoS ONE 9, e106966 (2014).

Hwang, J. S. et al. NFAT1 and JunB cooperatively regulate IL-31 gene expression in CD4+T cells in health and disease. J. Immunol. 194, 1963–1974 (2015).

Kim, H. J., Lee, H. J., Kim, H., Cho, S. W. & Kim, J.-S. Targeted genome editing in human cells with zinc finger nucleases constructed via modular assembly. Genome Res. 19, 1279–1288 (2009).

Huang, D. W., Sherman, B. T. & Lempicki, R. A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 (2009).

Daemen, A. et al. Modeling precision treatment of breast cancer. Genome Biol. 14, R110 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Irving Weissman (Stanford University, USA) and Dr. G-One Ahn (POSTECH, Korea) for kindly providing the MDA-MB-468/GFP cell line. This work was supported by the grants from the Institute for Basic Science (IBS-R005 for S.-H. Im).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C.K., H.-K.K. and S.-H.I. designed the studies and wrote the manuscript. G.C.K. performed most of the experiments and analyzed the data. C.-G.L, R.V., J.H.N., Y.K. and S.-H.I. participated in data acquisition and provided technical and intellectual support to the project. H.-K.K. and C.-G.L. participated in experiments. T.K. and K.K. performed RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data analysis, D.R. provided intellectual suggestions during the course of the study and edited the manuscript along with S.-H.I. S.-H.I. has full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data, as well as for the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, GC., Kwon, HK., Lee, CG. et al. Upregulation of Ets1 expression by NFATc2 and NFKB1/RELA promotes breast cancer cell invasiveness. Oncogenesis 7, 91 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41389-018-0101-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41389-018-0101-3

This article is cited by

-

Identification of hub genes to determine drug-disease correlation in breast carcinomas

Medical Oncology (2023)

-

LncRNA MAFG-AS1 promotes the malignant phenotype of ovarian cancer by upregulating NFKB1-dependent IGF1

Cancer Gene Therapy (2022)

-

Naringin Targets NFKB1 to Alleviate Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation/Reoxygenation–Induced Injury in PC12 Cells Via Modulating HIF-1α/AKT/mTOR-Signaling Pathway

Journal of Molecular Neuroscience (2021)

-

A novel immune-related prognostic index for predicting breast cancer overall survival

Breast Cancer (2021)

-

The pan-cancer landscape of netrin family reveals potential oncogenic biomarkers

Scientific Reports (2020)