Abstract

The globotriaosylceramide Gb3 is a glycosphingolipid expressed on a subpopulation of germinal center B lymphocytes which has been recognized as the B cell differentiation antigen CD77. Among tumoral cell types, Gb3/CD77 is strongly expressed in Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) cells as well as other solid tumors including breast, testicular and ovarian carcinomas. One known ligand of Gb3/CD77 is Verotoxin-1 (VT-1), a Shiga toxin produced in specific E. coli strains. Previously, we have reported that in BL cells, VT-1 induces apoptosis via a caspase-dependent and mitochondria-dependent pathway. Yet, the respective roles of various apoptogenic factors remained to be deciphered. Here, this apoptotic pathway was found to require cleavage of the BID protein by caspase-8 as well as activation of two other apoptogenic proteins, BAK and BAX. Surprisingly however, t-BID, the truncated form of BID resulting from caspase-8 cleavage, played no role in the conformational changes of BAK and BAX. Rather, their activation occurred under the control of full length BID (FL-BID). Indeed, introducing a non-cleavable form of BID (BID-D59A) into BID-deficient BL cells restored BAK and BAX activation following VT-1 treatment. Still, t-BID was involved along with FL-BID in the BAK-dependent and BAX-dependent cytosolic release of CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO from the mitochondrial intermembrane space: FL-BID was found to control the homo-oligomerization of both BAK and BAX, likely contributing to the initial release of CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO, while t-BID was needed for their hetero-oligomerization and ensuing release amplification. Together, our results reveal a functional cooperation between BAK and BAX during VT-1-induced apoptosis and, unexpectedly, that activation of caspase-8 and production of t-BID were not mandatory for initiation of the cell death process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The neutral glycosphingolipid globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) is strongly expressed in Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) cells [1] and various solid tumors including breast, testicular and ovarian carcinomas [2,3,4]. Gb3 is also found expressed in a subpopulation of germinal center B lymphocytes where it defines the CD77 differentiation antigen [5] and in intestine, kidney and brain endothelial cells. In the latter, Gb3 functions as a receptor for Shiga toxins (Stx) which are produced by the bacterial pathogens Shigella dysenteriae type 1 and by Stx-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), the main causative agent for food-poisoning worldwide [6]. Stxs produced by STECs are sometimes called Verotoxins (VTs), having been first described as lethal to Vero cells. All forms of Stxs consist of a single 32 kDa. A subunit linked non-covalently to a pentamer of B subunits (7.7 kDa each) which is responsible for Gb3/CD77 binding. Once internalized in the cytosol, the A subunit uses its enzymatic activity to remove an adenine residue from the 28S ribosomal RNA, resulting in protein synthesis inhibition (reviewed in [7, 8]).

Treating cells with Stxs/VTs in vitro induces apoptosis in a variety of tumor models. With a few exceptions such as HeLa cells where it is mitochondria-independent [9], the apoptotic process usually depends on both caspases and molecules stored in mitochondria [10,11,12]. In some cell types, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response induced by Stxs/VTs contributes to caspase 8 activation and thus also takes part in the apoptotic pathway [13]. It thus appears that Stxs/VTs can trigger different apoptotic pathways in different cell types and that a number of steps involved in these signaling cascades remain unknown.

Cytochrome C (CYT C) and second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase/direct IAP binding protein with low PI (SMAC/DIABLO) are two apoptogenic factors present in the intermembrane space (IMS) of mitochondria. When liberated into the cytosol following mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO trigger caspases activation and the downstream cell death machinery. The release of CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO is controlled by a combination of anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic members in the B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family which all contain BCL-2 homology (BH) domains referred to as BH1 to BH4. The pro-apoptotic group comprises effectors (mainly the BCL-2-antagonist/killer (BAK) and BCL-2–associated X protein (BAX) proteins) and another subgroup of proteins called “BH3-only” whose role is to regulate the effectors and the anti-apoptotic proteins. How they function precisely, however, remains controversial [14, 15]. There is no doubt that BAK and BAX are key players in MOMP as the two proteins form the pores through which the apoptogenic factors are released from the IMS. To do so, these two proteins must be activated by conformational modifications which result in the formation of oligomers and functional pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane but the precise mechanism thereof is intensely discussed [16, 17]. BID (BH3-interacting domain death agonist) is one of the BH3-only proteins which control BAK and BAX. It is the only one that behaves as a substrate for caspase-8 and other proteases including granzyme B, lysosomal cathepsins and calpains [18,19,20]. The role of t-BID, the resulting truncation product of BID, is recognized as critical in the apoptotic signaling pathway but how the full-length protein, FL-BID, also participates in the process is still a matter of debate [21, 22].

Previously, we have reported that the apoptosis induced by VT-1 in Gb3/CD77-expressing BL cell lines occurs via caspase-8 activation, a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and a cytosolic release of CYT C. BID, which was cleaved by caspase-8, and BAX were both involved in mitochondrial activation, but the accumulation of the latter at the mitochondrial membrane did not rely on t-BID [10, 23]. Here, this VT-1-induced apoptotic pathway has been further analyzed, revealing a requirement for FL-BID alone for BAK and BAX activation while t-BID and FL-BID were both needed for optimal BAK- and BAX-dependent cytosolic release of CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO. BAK and BAX each formed homo-oligomers under the specific influence of FL-BID but t-BID was additionally needed to trigger BAK-BAX hetero-oligomerization and probably for amplification of the cytosolic release of the apoptogenic factors.

Results

BID and the caspase-8 pathway are essential for VT-1 induced apoptosis

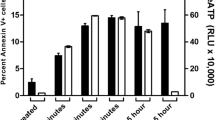

Previously, we demonstrated that the mitochondrial events induced by VT-1 in BL cells involved the cleavage of BID by caspase-8 [23]. To further investigate the role of BID (both full length and cleaved forms) in the apoptotic events induced by VT-1, we used two complementary approaches. First, we pretreated Ramos BL cells with the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK to prevent cleavage and activation of caspase-8 (Fig. 1a). As expected, this also inhibited the truncation of BID into t-BID (Fig. 1a; long exposure shows that treatment with Z-IETD inhibited the appearance of t-BID and short exposure that this treatment inhibited the decrease of FL-BID). Once treated with Z-IETD-FMK, Ramos cells became resistant to VT-1-induced apoptosis as measured by flow cytometry analysis of annexin-V-positive cells (38 ± 6 vs. 82 ± 4% in VT-1-treated control cells, p < 0.01, Fig. 1c). To directly analyze the role of BID, we then used a lentiviral vector-based shRNA system to stably repress its expression. The shBID reduced BID expression approximately 80% as compared to controls (Ramos shCTRL, Fig. 1b) without affecting the expression of the Gb3/CD77 VT-1 receptor at the cell membrane (Supplemental Fig. 1). These BID-repressed Ramos cells (Ramos shBID) proved much more resistant to VT-1-induced apoptosis than controls transduced with an empty vector (34 ± 4 vs. 83 ± 6% annexin-V-positive cells, respectively, p < 0.01, Fig. 1c). Consequently, and as anticipated, the cleavage of PARP strongly diminished in cells incubated in the presence of VT-1 whether they had been pretreated with Z-IETD-FMK (Fig. 1d, left panel) or if stably expressing shBID (Fig. 1d, right panel). Together, these observations confirmed that in these cells, both BID and the activity of caspase-8 are key elements in VT-1-induced apoptosis.

BID and the caspase-8 pathway are essential for VT-1-induced apoptosis. a Ramos cells preincubated (1 h) with or without the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK were treated or not with VT-1 for 6 h. Whole cell lysates were submitted to western blot analysis for detection of BID, caspase-8 and actin. b Whole cell lysates from Ramos cells stably transduced with a control shRNA vector (Ramos shCTRL) or with one directed against BID (Ramos shBID) were submitted to western blot analysis for detection of BID and actin. Fold change values as compared with the non-transduced cells and normalized to β-actin levels are shown above the BID blot. c Cells were incubated or not with VT-1 for 6 h and the proportion of apoptotic cells quantified by FACS analysis after labeling with annexin V-FITC and PI. Values (means ± sd) are from five independent experiments. Statistical significance is as follows: ***p < 0.01. d Cells were treated as in (c) and whole cell extracts submitted to western blot analysis for detection of PARP cleavage as a marker of apoptosis. Results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. In a, d black lines indicate that lanes were not contiguous in the gels

The activation of BAK and BAX is controlled by FL-BID, not by the caspase-8/t-BID pathway

From our previous studies, the VT-1-induced apoptosis in Ramos cells involves the mitochondrial relocalization of the pro-apoptotic BAX protein followed by MOMP and CYT C release [23]. BAX, and also BAK, get activated following a conformational change which, among other consequences, results in previously inaccessible N-terminal epitopes becoming accessible to conformation-dependent staining antibodies. Flow cytometry analysis with such antibodies showed that both BAK and BAX were activated in Ramos shCTRL cells incubated in the presence of VT-1 (78 ± 12 and 67 ± 5% of the cells respectively, Fig. 2a), stainings which were significantly inhibited in Ramos shBID cells (36 ± 7 and 27 ± 7% of the cells, p < 0.01 and p < 0.025, respectively, Fig. 2a and supplemental Fig. 2a for representative flow cytometry histograms). From these results, it was expected that BID-expressing Ramos cells treated with the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK would behave similarly to shBID-expressing cells. Surprisingly, however, following VT-1 treatment, both BAK and BAX remained activated in cells pretreated with Z-IETD-FMK (Fig. 2b and supplemental Fig. 2b) suggesting that t-BID played little role if any in BAK and BAX activation.

FL-BID controls BAK and BAX activation during VT-1-induced apoptosis. a Ramos shCTRL and Ramos shBID cells were treated or not with VT-1 for 6 h and analyzed by flow cytometry after labeling with anti-BAK (left) or anti-BAX (right) conformational antibodies. Statistical significance is as follows: **p < 0.025, n = 7; ***p < 0.01, n = 4. b Ramos cells preincubated (1 h) with or without the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK were treated or not with VT-1 for 6 h and analyzed by flow cytometry after labeling with anti-BAK (left) or anti-BAX (right) conformational antibodies. NS non significant, n = 3. c Membrane fractions were obtained from Ramos shCTRL and Ramos shBID cells (left) or from Ramos cells preincubated (1 h) with or without the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK (right), all treated or not with VT-1 for 6 h. Extracts were then incubated with proteinase K and analyzed by western blot for detection of BAK. d Cytosolic and mitochondrial extracts were obtained from cells treated as in (c) and were submitted to western blot analysis for detection of BAX, LDH, and cyclophilin D (used as cytosolic and mitochondrial markers, respectively). Results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. e BAX-specific bands in cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were quantified by densitometry, normalized to LDH or cyclophilin D levels and reported to the total amount of BAX (cytosolic + mitochondrial). Values (means ± sd) are from four (left) and three (right) independent experiments. Statistical significance is as follows: *** p < 0.01; NS non significant

These results were then confirmed by two other methods, limited proteolysis for BAK and mitochondrial localization for BAX. Indeed, following an apoptotic trigger, the exposure of its N-terminus renders BAK protein sensitive to proteinase K. Western blot analysis with an anti-BAK BH3 domain (Fig. 2c) shows that after treatment with VT-1, BAK became sensitive to proteinase K in Ramos cells, whether or not they had been pre-treated with Z-IETD-FMK. By contrast, after treatment with VT-1, BAK was much more resistant to proteinase K in Ramos shBID than in Ramos shCTRL cells. In healthy cells, BAX shuttles dynamically between cytosol and mitochondria but once activated, its shuttling towards the cytosol is inhibited and it accumulates in mitochondria [24]. Western blot analysis of cytosolic vs. mitochondrial extracts revealed that in Ramos and Ramos shCTRL cells treated with VT-1, BAX indeed accumulated in mitochondria. After VT-1 treatment, such an accumulation was not seen in Ramos shBID cells but was clearly observed in Ramos cells pretreated with Z-IETD-FMK (Fig. 2d and quantification of at least three experiments in Fig. 2e). From all these data, we conclude that it is the expression of full length BID rather than the caspase-8-dependent production of t-BID, which determines the stabilization of BAX and the mitochondrial activation of both BAK and BAX during VT-1-induced apoptosis.

To further substantiate these observations, we performed rescue experiments in Ramos-shBID cells whose transduction allowed for expression of histidine-tagged murine BID (mBID) proteins, one wild type (BID-WT), the other mutated (BID-D59A) to preclude cleavage of the encoded protein by caspase-8. It can be seen in Supplemental Fig. 3a that after 48 h, transduced shBID Ramos cells expressed large amounts of the murine version of BID with no difference between BID-WT and BID-D59A. As expected, the amount of BID-WT strongly decreased after VT-1 treatment whereas BID-D59A did not (supplemental Fig. 3b). Expression of the murine proteins significantly reconstituted the sensitivity of the Ramos shBID cells to VT-1 as assessed by an MTT cytotoxicity assay (Supplemental Fig. 3c), by annexinV/PI labeling of the cells (supplemental Fig. 3d) or by PARP cleavage (Supplemental Fig. 3e). This effect was observed with both the wild type and the non-cleavable version of mBID. The VT-1-induced activation of BAK and BAX was also measured by flow cytometry in cells expressing murine BID-WT or BID-D59A. Following VT-1 treatment, both BAK and BAX were activated in Ramos shCTRL (71 ± 15 and 74 ± 13% of the cells, respectively, Fig. 3a, b) but not in Ramos shBID cells (29 ± 7 and 30 ± 5% of the cells, respectively, Fig. 3a, b). Transducing the latter with BID-WT or BID-D59A significantly reconstituted the conformational changes of both BAK (in 62 ± 13 and 58 ± 9% of the cells, respectively, Fig. 3a and supplemental Fig. 4a for representative flow cytometry histograms) and BAX (in 52 ± 12 and 47 ± 5% of the cells, respectively, Fig. 3b and supplemental Fig. 4b). Similarly, the stabilization of BAX in mitochondria was significantly reconstituted in cells transduced either with BID WT or with BID-D59A (supplemental Fig. 5a and b). Together, these results further confirmed the implication of the full length BID protein in the activation of both BAK and BAX.

Expression of FL-BID restores BAK and BAX activation during VT-1-induced apoptosis of Ramos shBID cells. a Ramos shCTRL and Ramos shBID cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding either a mutated form of the murine BID protein (BID-D59A) which is not cleavable by caspase-8, a wild type version of murine BID (BID-WT) or a control empty vector. Forty hours after transduction, cells were incubated or not with VT-1 for 6 h and analyzed by flow cytometry after labeling with anti-BAK conformational antibodies. Values (means ± sd) are from seven independent experiments. b Cells transduced and treated as in (a) were labeled with anti-BAX conformational antibodies. Statistical significance is as follows: ***p < 0.01; NS non significant. Values (means ± sd) are from six independent experiments

Both FL-BID and caspase-8 activation are involved in CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO release from mitochondria

Having demonstrated that inhibiting caspase-8 with Z-IETD-FMK changed neither BAK and BAX activation nor BAX mitochondrial stabilization in response to VT-1 treatment, we then wished to explore what the effect would be on the release of apoptogenic IMS proteins from mitochondria to the cytosol. Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were prepared from Ramos cells preincubated with Z-IETD-FMK or not, as well as from shBID and shCTRL Ramos cells, all treated or not with VT-1. Western blots shown in Fig. 4a and quantifications of at least three experiments reported in Fig. 4b demonstrate that in VT-1-treated Ramos cells both CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO were released from mitochondria (70 ± 6 and 43 ± 4%, respectively) whereas the release of CYT C was reduced to 34 ± 6% (Fig. 4b upper panel, p < 0.025) and that of SMAC/DIABLO to 14 ± 5% (Fig. 4b lower panels, p < 0.05) in cells incubated in the presence of Z-IETD-FMK. This indicates that the activity of caspase-8 played a role in the release of these IMS proteins. We assume that this is through the truncation of BID into t-BID but we cannot rule out the possibility that another caspase-8 target may also play a role in conjunction with t-BID.

Both FL-BID and caspase-8 activation are involved in CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO release from mitochondria during VT-1-induced apoptosis. a Cytosolic and mitochondrial extracts from Ramos cells preincubated (1 h) with or without the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK (left) or from Ramos shCTRL and Ramos shBID cells (right), all treated or not with VT-1 for 6 h, were submitted to western blot analysis for detection of CYT C, SMAC/DIABLO, LDH and cyclophilin D (used as cytosolic and mitochondrial markers, respectively). Results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. b CYT C (upper graphics) and SMAC/DIABLO (lower graphics) specific bands in cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were quantified by densitometry, normalized to LDH or cyclophilin D levels and reported to the total amount (cytosolic + mitochondrial) of CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO. Values (means ± sd) are from four independent experiments. Statistical significance is as follows: **p < 0.025; *p < 0.05. c Ramos shCTRL and Ramos shBID cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding either a mutated form of the murine BID protein (BID-D59A) which is not cleavable by caspase-8, a wild type version (BID-WT) or a control empty vector. Forty hours after transduction, cells were treated or not with VT-1 for 6 h. Cytosolic and mitochondrial extracts were prepared and submitted to western blot analysis for detection of CYT C, SMAC/DIABLO, LDH and cyclophilin D (used as cytosolic and mitochondrial markers, respectively). d CYT C (upper graphics) and SMAC/DIABLO (lower graphics) specific bands in cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were quantified by densitometry, normalized to LDH or cyclophilin D levels and reported to the total amount (cytosolic + mitochondrial) of CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO. Values (means ± sd) are from four independent experiments. Statistical significance is as follows: ***p < 0.01; *p < 0.05

In Ramos shBID cells, the release of both CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO also decreased as compared to Ramos shCTRL cells (from 67 ± 4 to 24 ± 7%, and from 56 ± 7 to 30 ± 7%, respectively p < 0.025 in both cases, Fig. 4b). We then transduced Ramos shBID cells for expression of murine BID either WT or D59A. As seen in Fig. 4c, d, this resulted in a large increase of both CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO release from mitochondria which did not depend on whether BID could be cleaved into t-BID (BID-WT, 75 ± 19% of CYT C and 50 ± 7% of SMAC/DIABLO release) or not (BID-D59A, 70 ± 14% of CYT C and 49 ± 6% of SMAC/DIABLO release) as compared to Ramos shBID cells transduced with an empty vector (26 ± 9 and 31 ± 6%, respectively). From these data, we conclude that during VT-1-induced apoptosis, FL-BID on one hand and the caspase-8/t-BID pathway on the other hand are both involved in the release of the apoptogenic factors through BAK- and BAX-controlled MOMP.

The caspase-8/t-BID pathway is not involved in BAK and BAX homo-oligomerisation but controls BAK/BAX interaction

Since t-BID was not involved in the activation of BAK or BAX during the VT-1-induced apoptotic process, we wished to further analyze the respective effects of FL-BID and t-BID on the oligomerization of activated BAK and BAX proteins in mitochondria. To this aim, mitochondria were purified from Ramos cells treated with VT-1 or not, followed or not by protein cross-linking using bismaleimidohexane (BMH). Two blots were prepared in parallel with the same samples and blotted with either anti-BAK or anti-BAX antibodies. The BAK protein (apparent MW, 30 kDa) was readily detectable before VT-1 treatment (Fig. 5a, left panel, lanes 1 and 4) but treating the cells with VT-1 induced the formation of oligomers (mostly dimers and trimers) as seen in the crosslinked samples run in lanes 5 and 6 (Fig. 5a, left panel). Staining the second twin blot with anti-BAX antibodies confirmed that the 22 kDa monomeric BAX protein was detectable in these mitochondrial preparations more readily following than prior to VT-1 treatment (Fig. 5a, right panel, compare lanes 1 and 2), confirming the accumulation effect reported above. Here, oligomers and among them, dimers mainly, were the predominant forms observed after VT-1 treatment (Fig. 5a, right panel lane 5 and 6). For both BAK and BAX, the oligomers did not differ when production of t-BID was prevented with Z-IETD-FMK cell treatment (compare lanes 5 and 6 in both left and right panels). Also worth noting, the mobility of the BAK and BAX oligomers clearly differed, thus excluding the existence of hetero-oligomers.

The Caspase-8/t-BID pathway is not involved in BAK and BAX homo-oligomerisation but controls BAK/BAX interaction. a Ramos cells preincubated (1 h) with or without the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK, were treated or not with VT-1 for 6 h. Enriched mitochondrial fractions were prepared and treated with 0.5 mM bismaleimidohexane (BMH) crosslinker or DMSO (vehicle control) for 30 min. Protein extracts were analyzed by western blot for detection of BAK (left panel) and BAX (right panel). (*), (**), (***), (****) refer to protein monomers, dimers, trimers and quadrimers, respectively. (♦), intrachain cross-link conformer of inactive BAK. b Whole cell lysates from Ramos cells preincubated (1 h) with or without the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK and treated or not with VT-1 for 6 h were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using a rabbit anti-BAX pAb or control rabbit IgG (upper panel) or using a goat anti-BAK pAb or control goat IgG (lower panel). The immunoprecipitated proteins were submitted to western blot analysis for detection of BAK or BAX. (Input), 15% of the input for IP were included in the blot as a control for pre-IP protein levels. c Ramos shCTRL and Ramos shBID cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding either a mutated form of the murine BID protein (BID-D59A) which is not cleavable by caspase-8, a wild type version of murine BID (BID-WT) or an empty control vector. Forty hours after transduction, cells were incubated or not with VT-1 for 6 h and submitted to immunoprecipitations followed by western blots performed as in (b)

To further investigate whether BAK and BAX directly interacted during the VT-1-induced apoptotic process, we then submitted total Ramos cell extracts to either BAK or BAX immunoprecipitation and then looked for co-immunoprecipitation of the other protein. As seen in Fig. 5b, precipitating BAX coimmunoprecipitated BAK only after VT-1 treatment (compare lanes 2 and 5 in upper panels). Reciprocally, precipitating BAK after VT-1 treatment coimmunoprecipitated BAX, although with less efficiency (compare lanes 2 and 5 in lower panels). These results which contrast with those obtained after protein cross-linking, suggested the existence of direct interactions between BAK and BAX. Two different reasons might explain this apparent contradiction. The failure to cross-link BAK and BAX using BMH might be due to steric factors related to the nature of the cross-linker and/or to the conformation of the proteins. Alternatively, not detecting the hetero-oligomers on gels could reflect their low abundance as compared to the homo-oligomers. When Ramos cells were pre-incubated with Z-IETD-FMK, the co-immunoprecipitation of BAK and BAX was inhibited almost to background levels (compare lanes 5 and 8 in upper and lower panels), indicating that the interaction between these two proteins requires the cleavage of BID by caspase-8.

To further explore the relationship between the caspase-8/t-BID pathway and the interaction between BAX and BAK, we finally submitted Ramos shCTRL and shBID cells to the same coimmunoprecipitation experiments. As can be seen in Fig. 5c, the VT-1 treatment led to BAK/BAX being co-immunoprecipitated in the former (lane 4) but much less in the latter (lane 9). Transducing Ramos shBID cells with the BID-WT expression vector restored the BAK/BAX interaction as detected by co-immunoprecipitation of one protein with antibodies to the other (Fig. 5c, lane 14). This contrasted with Ramos shBID cells transduced with the expression vector for the D59A non-cleavable mutant form of BID in which the BAK/BAX co-immunoprecipitation remained minimal as in Ramos shBID parental cells (Fig. 5c, lane 19). From these results, we conclude that although BAK and BAX can each oligomerize independently of t-BID in VT-1-treated cells, hetero-oligomers form only if the truncated form of BID is produced.

Discussion

Different signaling pathways triggered by Stxs/VTs have been described in various cell types but many steps in these pathways remain to be deciphered [25]. Here, we detail the sequence of events in the VT-1-induced apoptotic pathway and for the first time we demonstrate a cooperative activity between FL-BID and t-BID for a strong and complete apoptosis. In our previous studies, we had shown that the VT-1-induced apoptosis required degradation of the caspase-8 inhibitory molecule c-FLIPL through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway and that BAX relocalization to mitochondrial membranes participated in the MOMP which leads to CYT C release [10, 23]. In this paper, we have now demonstrated that BAK also is involved in MOMP and that SMAC/DIABLO as well as CYT C are released from the mitochondria during VT-1-induced apoptosis. Most importantly, our results show that the production of t-BID by caspase-8 is involved neither in BAX relocalization and activation nor in BAK activation; rather, both events are controlled by FL-BID. Finally, we have also shown that the caspase-8/t-BID pathway is not involved in the VT-1-induced homo-oligomerization of BAK and BAX but is needed for the BAK/BAX hetero-oligomerization and that both FL-BID and the caspase-8/t-BID pathway are involved in the MOMP-dependent release of CYT C and SMAC/DIABLO. Together, our data strongly suggest that under the control of FL-BID and t-BID, the homo-oli and hetero-oligomers of BAK and BAX act in coordination to insure a maximal release of the apoptogenic proteins and thereby an efficient apoptosis in cells treated with VT-1.

Other groups have reported that endogenous FL-BID functions as an apoptotic regulator for intrinsic cell death pathways. Studying the role of BID during TNF-α-induced apoptosis, Pei et al. reported that FL-BID directly interacted with BAX in the cytosol after TNF-α treatment and that this interaction induced BAX relocalization to the mitochondria. They also showed that BID cleavage is a relatively late event in the apoptotic process [22]. Sarig et al., who produced the BID-D59A mutated form of BID, showed that expression of this non-cleavable form of BID efficiently induced apoptosis in primary MEFs. They also demonstrated that the apoptosis induced by BID-D59A did not involve its translocation to the mitochondria nor massive CYT C release, but still depended upon BAX and BAK activation [26], On the other hand, Valentijn and Gilmore have reported that FL-BID translocates to the mitochondria during anoikis, a form of apoptosis which occurs upon detachment of epithelial cells from the extracellular matrix, and that its translocation is independent of interactions with BAX [27]. Thus, it will be of interest to determine if during VT-1-induced apoptosis BAX activation requires interaction with FL-BID in the cytosol and whether or not FL-BID translocates to the mitochondria.

It is currently held that the N-terminal protein processing of BID by proteases exposes its BH3 domain and results in the translocation of t-BID to mitochondria where it activates its targets [15]. In contrast, the mechanism of action of FL-BID during apoptosis and its relocalization to the mitochondria is still very poorly understood. Interestingly, it has been shown that FL-BID but not t-BID is able to insert specific lysolipids into the mitochondrial membrane and that these specific changes probably prime mitochondria outer membranes to the actions of BAK and BAX which then induce the release of apoptogenic proteins [28]. Recently, the role of mitochondrial membrane lipids, and most notably of cardiolipin, in the t-BID-promoted activation of BAK and BAX has been confirmed [17]. However, it has also been reported that cardiolipin and the MTCH2 (mitochondrial carrier homolog 2) protein have redundant functions as t-BID receptors in the mitochondrial membrane [29]. Thus, determining the lipid and lysolipid composition of membrane mitochondria before and after treatment with VT-1 will certainly improve our understanding of how FL-BID and t-BID act during this process.

Also importantly, we have shown here that homo-oligomers and hetero-oligomers of BAK and BAX play complementary roles during VT-1-induced apoptosis. The release of IMS proteins from mitochondria is a crucial step in apoptotic signaling [30]. Several studies have pointed towards a major role for BAX in CYT C release based on its ability to form channels in artificial lipid membranes [31, 32] and large oligomeric complexes in the mitochondrial outer membrane [33, 34]. Recently, thanks to super-resolution microscopy approaches, two groups have also reported the presence of large ring-like structures in mitochondria of apoptotic cells [35, 36]. Although the formation of these transmembrane channels by BAX oligomers is a likely explanation, the question of how BAX triggers CYT C release after its translocation to mitochondria continues to be debated. We have now demonstrated that treating cells with VT-1 induced relocalization and formation of BAX oligomers in the mitochondrial outer membrane but also a reorganization of BAK monomers into oligomers. Analyzing the molecular sizes of cross-linked BAX and BAK complexes indicated that both BAX and BAK essentially form homo-oligomers. However, our results also showed that BAK and BAX co-immunoprecipitated, thereby revealing an interaction which occurred after BAX had undergone conformational changes to oligomerize. Although it has been shown that either BAK or BAX can be sufficient to elicit apoptosis, it is generally admitted that the apoptotic process is more complete and efficient when both BAX and BAK are present. Based on the data reported here, it is tempting to speculate that the interactions between these two proteins insure the most efficient MOMP. Inside mitochondria, CYT C and most certainly SMAC/DIABLO are present in different locations: a minor pool is free in the IMS, a major pool enclosed in cristae [37]. Hence, IMS proteins are likely released in two successive steps after MOMP: first, their soluble pool then the pool present in cristae. Interestingly, it has been shown that the oligomerization of a dynamin-related protein of the mitochondrial inner membrane, OPA-1, controls the morphology of cristae and CYT C redistribution during apoptosis. t-BID is involved in this mitochondrial cristae reorganization both by disrupting OPA-1 oligomers [38] and interacting with cardiolipin at mitochondrial contact sites [39]. From these various data and ours, we propose that the soluble pools of the IMS apoptogenic factors are released through BAK and BAX homo-oligomers and only require the action of FL-BID. In contrast, the pools present in cristae would be released only when t-BID is present and involves the formation of BAK/BAX hetero-oligomers. We also assume that BAK and BAX homo-oligomerization triggers the initial release of IMS proteins and that the caspase-8/t-BID pathway activates an amplification loop by inducing BAK/BAX interactions. For such a mechanism, it is likely that the majority of oligomers should be homo-structures, which would explain why we did not detect hetero-oligomers on gels after BMH cross-linking. Interestingly, this scheme is in line with the recent reports of Grosse et al. and Salvador-Gallego et al. who, among homogeneously labeled BAX rings, also noticed the presence of some heterogeneously-labeled structures which they assumed corresponded to assemblies of BAX with other proteins [35, 36].

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Culture conditions of Ramos cell line (ATCC CRL-1596) were previously described in Garibal et al. [23]. Stable BID-repressed Ramos cells (Ramos shBID) were established after transduction of a shRNA targeting BID (Mission® shRNA lentiviral transduction particles SHCLNV-NM 001196, Sigma Aldrich) and control Ramos cells (Ramos shCTRL) after transduction of a control shRNA (Mission® non-target shRNA lentiviral transduction particles, SHC002V). Cells were transduced according to the manufacturer’s protocol and then selected by adding puromycin (0.6 mg/ml) to the culture medium.

Vectors and lentiviral transduction

pLVX-IRES-ZS-Green Bid-wt, Bid-D59A and empty lentiviral vectors, derived from vectors produced in A. Gross laboratory [26], were a gift from Susin [40]. Viruses were produced into 293T cells by Jetprime (Polyplus) transient transfection of lentiviral constructs and the packaging plasmids pDM2G (gift from Didier Trono, Addgene plasmid # 12259) and pCMVdelta R8.2 (gift from Didier Trono, Addgene plasmid # 12263). Two days after transfection, lentiviral supernatants were harvested, clarified by filtration and concentrated by ultracentrifugation. BL cells (2 × 106) were transduced with lentiviral particles (at a MOI of 15) in 2 ml of fresh medium in six-well plates and incubated 24 h at 37 °C. The medium containing lentiviral particles was then removed and fresh medium was added. The cells were harvested 24 or 48 h after transduction and used for further experiments.

Reagents and antibodies

Purified recombinant verotoxin-1 (VT-1) was purchased from List Biological Laboratories, Inc. Caspase-8 inhibitor (Z-IETD-FMK) was obtained from Calbiochem. Primary antibodies: Mouse anti-caspase-8 mAb (Ab-3, clone 1-3, Calbiochem), mouse anti-poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase (PARP) mAb (Ab-2, clone c-2-10, Calbiochem), mouse anti-BAK conformational mAb (ab-1, Calbiochem), rabbit anti-BAK pAb (Becton-Dickinson), rabbit anti-BID pAb (FL195, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc), rabbit anti-BAX pAb (N-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc), mouse anti-BAX conformational mAb (6A7, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-CYT C mAb (7H8.2C12, Becton-Dickinson), rabbit anti-SMAC/DIABLO pAb (Imgenex), mouse anti-histidine mAb (His-1, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-β actin mAb (AC-74, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) mAb (H-10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) and anti-cyclophilin mAb (E11AE12BD4, Mitosciences). Mouse anti-Gb3/CD77 mAb (1A4) was a gift from Dr. S. Hakomori and rat anti-BAK (4B5) mAb, which recognize the BAK BH3 domain, from Dr. R Kluck [41]. Secondary antibodies: horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare), HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc), Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Life technologies).

Apoptosis measurement

Apoptosis was assessed by labeling cells with annexin-V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) as previously described [23]. Cells were then analyzed (n = 10,000) by flow cytometry (Accuri C6 cytometer, Becton-Dickinson). Annexin V-positive cells (PI negative and positive) were counted as apoptotic.

Intracellular immunofluorescence

BAK and BAX conformational changes were tested by flow cytometry using conformational antibodies. Cells, treated or not with VT-1 for 6 h, were harvested, fixed in paraformaldehyde (0.25%, 5 min) and washed three times in PBS before being incubated for 30 min with antibodies diluted (1:100 for anti-BAK (Ab-1), 1:200 for anti-BAX (6A7)) in PBS containing digitonin (500 μg/ml). After three washes in PBS, cells were incubated with Alexa-488-labeled anti-mouse antibodies for 30 min, washed twice, and analyzed by flow cytometry (Accuri C6 cytometer, Becton-Dickinson).

Preparation of whole cell extract

Aliquots of 1 × 106 cells were pelleted, solubilized in ice-cold RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP40, 0.5% NaDOC, 0.1% SDS, complete protease inhibitor) and sonicated. Total protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay (Biorad).

Preparation of mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions

Cell fractionation using ice-cold cell lysis and mitochondria intact (CLAMI) buffer was performed as previously described [10].

Isolation of mitochondria and cross-linking

Pellets obtained from 24 × 106 cells were resuspended in sucrose buffer (25 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES, 2 mM EDTA, complete protease inhibitor) and incubated 30 min on ice. Sucrose buffer was supplemented with sucrose 1 M to reach 250 mM concentration and cells were broken by using a dounce. The suspension was centrifuged at 600×g for 10 min to remove nucleus and cell debris. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 15,000×g at 4 °C for 15 min and the mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in 250 mM sucrose buffer, pH 7. Bis(maleimido)hexane (BMH) crosslinker or DMSO (vehicle control) was added to the mitochondria at 0.5 mM final concentration and the reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was then stopped by quenching with DTT (final concentration 50 mM) for 15 min.

Limited proteolysis assay

BAK sensitivity to proteinase K was used to evaluate its conformational change. Membrane extracts enriched for mitochondria were incubated with proteinase K (30 μg/ml) as previously described by Iyer et al. [42]. Samples were then immunoblotted with the 4B5 anti-BAK mAb.

Immunoprecipitation

BAK and BAX immunoprecipitations were performed as previously described [23] using agarose-conjugated rabbit anti-BAX pAb (N-20) or goat anti-BAK pAb (G-23) or agarose-conjugated control rabbit IgG or agarose-conjugated control goat IgG (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.)

Western blot analysis

Immunoblotting of protein extracts was carried out as previously described [23]. The blots were imaged with the ImageQuant LAS4000 imager (GE healthcare) and then on film (Amersham). Densitometry analysis of the blots was carried out using Quantity One software, version 4.6 (Bio-Rad).

Data analysis and statistic

All values for statistical significance represent the mean ± standard deviation (sd). Statistical analyses were performed using a non-parametric two-tailed test (n < 30): Mann and Whitney for side-by-side comparison and Holm correction was applied for multiple comparisons.

References

Nudelman E, Kannagi R, Hakomori S, Parsons M, Lipinski M, Wiels J, et al. A glycolipid antigen associated with Burkitt lymphoma defined by a monoclonal antibody. Science. 1983;220:509–11.

Arab S, Russel E, Chapman WB, Rosen B, Lingwood CA. Expression of the verotoxin receptor glycolipid, globotriaosylceramide, in ovarian hyperplasias. Oncol Res. 1997;9:553–63.

Gupta V, Bhinge KN, Hosain SB, Xiong K, Gu X, Shi R, et al. Ceramide glycosylation by glucosylceramide synthase selectively maintains the properties of breast cancer stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:37195–205.

Ohyama C, Fukushi Y, Satoh M, Saitoh S, Orikasa S, Nudelman E, et al. Changes in glycolipid expression in human testicular tumor. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:1040–4.

Mangeney M, Richard Y, Coulaud D, Tursz T, Wiels J. CD77: an antigen of germinal center B cells entering apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:1131–40.

Jacewicz M, Clausen H, Nudelman E, Donohue-Rolfe A, Keusch GT. Pathogenesis of shigella diarrhea. XI. Isolation of a shigella toxin-binding glycolipid from rabbit jejunum and HeLa cells and its identification as globotriaosylceramide. J Exp Med. 1986;163:1391–404.

Bergan J, Dyve Lingelem AB, Simm R, Skotland T, Sandvig K. Shiga toxins. Toxicon. 2012;60:085–107. 1

Johannes L, Romer W. Shiga toxins--from cell biology to biomedical applications. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:105–16.

Fujii J, Matsui T, Heatherly DP, Schlegel KH, Lobo PI, Yutsudo T, et al. Rapid apoptosis induced by Shiga toxin in HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2724–35.

Tetaud C, Falguieres T, Carlier K, Lecluse Y, Garibal J, Coulaud D, et al. Two distinct Gb3/CD77 signaling pathways leading to apoptosis are triggered by anti-Gb3/CD77 mAb and verotoxin-1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45200–8.

Lee SY, Cherla RP, Caliskan I, Tesh VL. Shiga toxin 1 induces apoptosis in the human myelogenous leukemia cell line THP-1 by a caspase-8-dependent, tumor necrosis factor receptor-independent mechanism. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5115–26.

Ching JC, Jones NL, Ceponis PJ, Karmali MA, Sherman PM. Escherichia coli shiga-like toxins induce apoptosis and cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase via in vitro activation of caspases. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4669–77.

Tesh VL. Activation of cell stress response pathways by Shiga toxins. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:1–9.

Tait SW, Green DR. Mitochondrial regulation of cell death. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2013;5:pii:a008706. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a008706

Zheng JH, Viacava Follis A, Kriwacki RW, Moldoveanu T. Discoveries and controversies in BCL-2 protein-mediated apoptosis. FEBS J. 2016;283:2690–2700.

Li MX, Dewson G. Mitochondria and apoptosis: emerging concepts. F1000 prime Rep. 2015;7:42.

Renault TT, Chipuk JE. Death upon a kiss: mitochondrial outer membrane composition and organelle communication govern sensitivity to BAK/BAX-dependent apoptosis. Chem Biol. 2014;21:114–23.

Chen M, He H, Zhan S, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Gottlieb RA. Bid is cleaved by calpain to an active fragment in vitro and during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30724–8.

Cullen SP, Adrain C, Luthi AU, Duriez PJ, Martin SJ. Human and murine granzyme B exhibit divergent substrate preferences. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:435–44.

Li H, Zhu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J. Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 1998;94:491–501.

Konig HG, Rehm M, Gudorf D, Krajewski S, Gross A, Ward MW, et al. Full length Bid is sufficient to induce apoptosis of cultured rat hippocampal neurons. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8:7.

Pei Y, Xing D, Gao X, Liu L, Chen T. Real-time monitoring full length bid interacting with Bax during TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1681–90.

Garibal J, Hollville E, Renouf B, Tetaud C, Wiels J. Caspase-8-mediated cleavage of Bid and protein phosphatase 2A-mediated activation of Bax are necessary for Verotoxin-1-induced apoptosis in Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. Cell Signal. 2010;22:467–75.

Todt F, Cakir Z, Reichenbach F, Emschermann F, Lauterwasser J, Kaiser A, et al. Differential retrotranslocation of mitochondrial Bax and Bak. EMBO J. 2015;34:67–80.

Tesh VL. Induction of apoptosis by Shiga toxins. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:431–53.

Sarig R, Zaltsman Y, Marcellus RC, Flavell R, Mak TW, Gross A. BID-D59A is a potent inducer of apoptosis in primary embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10707–15.

Valentijn AJ, Gilmore AP. Translocation of full-length Bid to mitochondria during anoikis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32848–57.

Goonesinghe A, Mundy ES, Smith M, Khosravi-Far R, Martinou JC, Esposti MD. Pro-apoptotic Bid induces membrane perturbation by inserting selected lysolipids into the bilayer. Biochem J. 2005;387(Pt 1):109–18.

Raemy E, Montessuit S, Pierredon S, van Kampen AH, Vaz FM, Martinou JC. Cardiolipin or MTCH2 can serve as tBID receptors during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:1165–74.

Ghiotto F, Fais F, Bruno S. BH3-only proteins: the death-puppeteer’s wires. Cytom A. 2010;77:11–21.

Antonsson B, Conti F, Ciavatta A, Montessuit S, Lewis S, Martinou I, et al. Inhibition of Bax channel-forming activity by Bcl-2. Science. 1997;277:370–2.

Saito M, Korsmeyer SJ, Schlesinger PH. BAX-dependent transport of cytochrome c reconstituted in pure liposomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:553–5.

Kuwana T, Mackey MR, Perkins G, Ellisman MH, Latterich M, Schneiter R, et al. Bid, Bax, and lipids cooperate to form supramolecular openings in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Cell. 2002;111:331–42.

Karch J, Kwong JQ, Burr AR, Sargent MA, Elrod JW, Peixoto PM. et al. Bax and Bak function as the outer membrane component of the mitochondrial permeability pore in regulating necrotic cell death in mice. Elife. 2013;2:e00772

Grosse L, Wurm CA, Bruser C, Neumann D, Jans DC, Jakobs S. Bax assembles into large ring-like structures remodeling the mitochondrial outer membrane in apoptosis. EMBO J. 2016;35:402–13.

Salvador-Gallego R, Mund M, Cosentino K, Schneider J, Unsay J, Schraermeyer U, et al. Bax assembly into rings and arcs in apoptotic mitochondria is linked to membrane pores. EMBO J. 2016;35:389–401.

Scorrano L, Ashiya M, Buttle K, Weiler S, Oakes SA, Mannella CA, et al. A distinct pathway remodels mitochondrial cristae and mobilizes cytochrome c during apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2002;2:55–67.

Frezza C, Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Micaroni M, Beznoussenko GV, Rudka T, et al. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell. 2006;126:177–89.

Kim TH, Zhao Y, Ding WX, Shin JN, He X, Seo YW, et al. Bid-cardiolipin interaction at mitochondrial contact site contributes to mitochondrial cristae reorganization and cytochrome C release. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3061–72.

Cabon L, Galan-Malo P, Bouharrour A, Delavallee L, Brunelle-Navas MN, Lorenzo HK, et al. BID regulates AIF-mediated caspase-independent necroptosis by promoting BAX activation. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:245–56.

Dewson G, Kratina T, Sim HW, Puthalakath H, Adams JM, Colman PM, et al. To trigger apoptosis, Bak exposes its BH3 domain and homodimerizes via BH3:groove interactions. Mol Cell. 2008;30:369–80.

Iyer S, Anwari K, Alsop AE, Yuen WS, Huang DC, Carroll J, et al. Identification of an activation site in Bak and mitochondrial Bax triggered by antibodies. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11734.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yann Lécluse (Imaging and Cytometry Platform, Institut Gustave Roussy) for expert technical assistance in performing flow cytometry analyses. We are very grateful to Hana Raslova and Julie Rivière (INSERM UMR 1170, Institut Gustave-Roussy) for their help in producing lentivirus and to Evelyne May and Martine Raphaël (UMR 8126 CNRS) for helpful discussions and suggestions. This work was supported by grants from the Fondation de France 2014 00047509 (JW), the Ligue National Contre le Cancer (doctoral fellowship to JD) and the Fondation ARC (doctoral fellowship to EH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, and provide a link to the Creative Commons license. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Debernardi, J., Hollville, E., Lipinski, M. et al. Differential role of FL-BID and t-BID during verotoxin-1-induced apoptosis in Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. Oncogene 37, 2410–2421 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0123-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0123-5

This article is cited by

-

Dual targeting of BCL-2 and MCL-1 in the presence of BAX breaks venetoclax resistance in human small cell lung cancer

British Journal of Cancer (2023)

-

Mining prognostic markers of Asian hepatocellular carcinoma patients based on the apoptosis-related genes

BMC Cancer (2021)

-

KIF15 is involved in development and progression of Burkitt lymphoma

Cancer Cell International (2021)

-

Dual targeting of BCL2 and MCL1 rescues myeloma cells resistant to BCL2 and MCL1 inhibitors associated with the formation of BAX/BAK hetero-complexes

Cell Death & Disease (2020)